Abstract

Objective

We compared the distribution by wealth of self-reported illness burden (estimated from validated scales, biomarker and reported symptoms) for angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis, with the distribution of self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment. We aimed to determine if the greater illness burden borne by poorer participants was matched by appropriately higher levels of diagnosis and treatment.

Design

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, a panel study of 12 765 participants aged 50 years and older in four waves from 2004 to 2011, selected using a stratified random sample of households in England. Distribution of illness burden, diagnosis and treatment by wealth was estimated using regression analysis.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures were ORs for the illness burden, diagnosis and treatment, respectively, adjusted for age, sex and wealth. We estimated the illness burden for angina with the Rose Angina scale, diabetes with fasting glycosylated haemoglobin, depression with the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, osteoarthritis with self-reported pain and disability and cataract with self-reported poor vision. Medical diagnoses were self-reported for all conditions. Treatment was defined as β-blocker prescription for angina, surgery for osteoarthritis and cataract, and receipt of predefined effective interventions for diabetes and depression.

Results

Compared with the wealthiest, the least wealthy participant had substantially higher odds for illness burden from any of the five conditions at all four time points, with ORs ranging from 4.2 (95% CI 2.6 to 6.8) for diabetes to 15.1 (11.4 to 20.0) for osteoarthritis. The ORs for diagnosis and treatment were smaller in all five conditions, and ranged from 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) for diabetes treatment to 4.5 (3.3 to 6.0) for angina diagnosis.

Conclusions

The substantially higher illness burden in less wealthy participants was not matched by appropriately higher levels of diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) is a unique single source of detailed data on socioeconomic status and health, and this is the first study to compare inequalities in illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment of long-term conditions in a panel study over time.

Highly detailed measures of individual wealth were used alongside standardised scales and blood biomarker to assess the illness burden of depression, angina and diabetes.

Standardised scales were not included in ELSA for osteoarthritis and cataract, so assessment of illness burden for these two conditions was based on attributed symptoms which were not specific for osteoarthritis and cataract.

The study used self-reported data collected using an extensively tested structured questionnaire, but no information from medical records was collected.

An analysis of pooled data from four waves of ELSA was used to maximise the sample size, and the main finding that less wealthy participants are relatively underdiagnosed requires validation in a larger longitudinal study.

Introduction

Poverty is associated with poor health, poor access to healthcare and poor health outcomes in many countries and across different healthcare systems.1–3 Much of this variation is caused by recognised broad social determinants of health.4 Considerable political effort has been directed at attempts to narrow health inequalities by reducing poverty and social exclusion. However, as healthcare has become more effective at improving health, its potential contribution to ameliorating health inequalities has increased. McKeown demonstrated in the 1970s that health services had contributed little to health improvement,5 but the same claim could not be made today. The past 30 years have seen the introduction of a wide range of effective interventions, particularly for the prevention and management of chronic disease.6 Yet although these new interventions improve health, they are not necessarily applied equally across the population. Health inequalities will widen if effective services are offered, or taken up, with greater frequency by wealthier than less wealthy people. The reverse is also true, however, and there is an opportunity for healthcare to reduce social inequalities if it reaches those most in need.7

Little is known about pathways into poor health. The National Health Service provides medical care free at point-of-need to all UK residents, but there is scope for inequalities to occur in the pathway from identification of early symptoms through diagnosis and on to effective treatment. Individuals in more deprived social groups may be more reluctant to present to doctors with their symptoms and so may not receive a diagnosis.8 9 Diagnosis is a key step that has meaning for both patient and physician in all health systems, and ‘diagnostic confusion’ may act as a barrier to healthcare for vulnerable populations.8 10 11 Previous studies have found socioeconomic variation in either diagnosis or treatment rates, but have not been able to compare inequalities in illness burden, rates of diagnosis and treatment modalities in the same population.12–14

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) provides new data that can be used to identify barriers to equitable receipt of healthcare, and constitutes a unique source of information on illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment. Other data sources cover symptoms or diagnosis or treatment, but no other single source covers all three. ELSA collects data on symptoms and validated markers of common health conditions, as well as diagnosis and treatment. It also contains detailed sociodemographic information, including direct measures of personal wealth, on a sample selected to be representative of the population of England aged 50 years and older. These data can be used to compare socioeconomic inequalities for several conditions, providing insight into a healthcare system with no direct financial barriers to treatment (the National Health Service in England). We aimed to assess socioeconomic inequalities in the burden of illness (estimated by validated scales, biomarker and reported symptoms) of angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis, and compare them with inequalities in self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment, in order to determine whether key components of healthcare were received equitably.

Methods

We obtained data from the ELSA cohort, an interview survey of a sample of the population aged 50 years or older in England. The sample was selected from households that had previously responded to the Health Survey for England, and drawn from selected postcode sectors stratified by health authority and deprivation to be representative of adults aged 50 or more living in private households in England.15 Participants are interviewed in their homes or care homes every 2 years about a wide range of health, economic and social topics. We used data collected from core participants who had been interviewed in any of four waves of ELSA from wave 2 in 2004–2005 until wave 5 in 2010–2011. Wave 2 was the first wave to include questions on receipt of quality-indicated healthcare, and information was not collected on every variable in every wave. We studied five common and important long-term conditions: angina, diabetes, depression, osteoarthritis and cataract. Effective treatment is freely available for all five conditions from the National Health Service.

Variables

We collected data on illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment of angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis. The illness burden for angina was defined as grade 2 on the Rose Angina scale (pain or discomfort in chest when walking at an ordinary pace on the level on most occasions or more often, which makes participant stop or slow down if occurs while walking, and which then goes away within 10 min, and which includes either sternum (any level), or left arm and left anterior chest). Illness burden for diabetes was defined as a fasting glycosylated haemoglobin level of >7.5%.16 Illness burden for depression was defined as a score of 3 or more on the eight-item Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The application of these standardised scales in ELSA has been described previously.1 Illness burden for osteoarthritis was defined as self-reported pain in the hip or knee of 5 or more on a scale of 0–10.17 Illness burden for cataract was defined broadly as reporting poor vision or blindness. Cataract is responsible for about a quarter of poor vision in the UK, so this measure is the least specific and includes those with other causes of poor vision, such as age-related macular degeneration, which is responsible for about a third of poor vision.18 19

A medical diagnosis was considered to exist if a participant answered ‘yes’ when asked whether a doctor had ever told them they had the condition of interest. For arthritis, a follow-up question asked whether they had been told they had osteoarthritis, rheumatoid or other arthritis.

Treatment for depression and diabetes was defined by reported achievement of quality of care indicators, derived through a robust process of literature reviews, expert panel assessment and piloting.20 21 For depression, the quality indicator was about receipt of treatment since the previous wave: “if a person is diagnosed with clinical depression, then antidepressive treatment, talking treatment or electroconvulsive treatment should be offered within 2 weeks after diagnosis unless within that period the patient has improved, or unless the patient has substance abuse or dependence, in which case treatment may wait until 8 weeks after the patient is in a drug-or alcohol-free state.” For diabetes, treatment was measurement of HbA1c or fructosamine levels in the preceding 12 months. Treatment for angina was defined as ever being offered or currently taking β-blockers (ELSA variables hebeta or hebetb). Treatment for osteoarthritis and cataract was defined as reporting ever having had surgery for the condition. For osteoarthritis, this excluded those with hips or knees replaced due to fracture. Data on hip and knee replacements were only available for respondents aged 60 and over, and so respondents aged less than 60 years (n=3186) were excluded from the analysis of osteoarthritis.

Wealth was defined as the sum of financial, physical and housing wealth plus state and private pension income. Age was categorised into three groups: 50–59, 60–74 and 75 years and older.

Analysis

We used two approaches to analysis, a main analysis using serial cross-sectional data and then a subsidiary analysis using longitudinal data. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used, with the outcome variables defined as one of illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis or treatment for each of the five conditions in each cross-sectional wave (STATA statistical software V.12.1). This regression analysis was repeated for each of the four waves of ELSA from 2004 to 2011 separately and then ‘overall’ for all four waves combined. For the ‘overall’ analysis, the data were reshaped into ‘long’ format in Stata statistical software, with each participant having a separate record for each wave. Intraperson correlation of outcomes was accounted for using robust adjustment with Stata, with each participant's unique identifier included in the regression equation as a cluster variable. Missing data were excluded from the analyses.

The independent variables were age group, sex and slope order of inequality. We used the slope order of inequality as an independent variable to estimate the relationship between the outcome measures and the categorised measure of wealth.22 23 The slope order of inequality consisted of wealth quintiles with values of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9, that is, the midpoints of each quintile on a scale of zero (least wealthy) to one (most wealthy). The slope order of inequality was modelled as a continuous variable, so that the slope or coefficient of a logit linear regression line across all five quintiles represents the difference in outcome between the hypothetically wealthiest and least wealthy participant. Exponentiating this slope coefficient results in an OR, which is the ratio of the odds of the outcome in the wealthiest compared with the least wealthy participant. This OR is also known as a relative index of inequality.22 Advantages of this method of quantifying inequality are that it includes all participants, instead of just comparing the highest and lowest quintiles, it accounts for the number of participants in each category and it provides a single overall measure of inequality.

We included all participants in the main cross-sectional analysis in order to compare the distribution of illness burden in the whole population with the distributions of diagnoses and treatments in the whole population. This meant that diagnosis was assessed even in those who did not meet the criteria for ‘illness burden’, and treatment was assessed even in those with no diagnosis. For the subsidiary analysis using longitudinal data, we estimated the OR of receiving a diagnosis by a subsequent wave only for those who had met the criteria for ‘illness burden’ in a previous wave, and then the likelihood of receiving treatment only for those who had received a diagnosis in a previous wave. This was a subsidiary analysis as the number of participants that could be followed over time in this manner was small, particularly for treatment in angina and depression.

Results

The whole sample (n=12 765) was composed of participants aged 50 years or more who had responded to at least one wave of ELSA from 2004–2005 until 2010–2011. The response rate in 2004–2005 was 82%.24 25 In wave 5 (2010–2011), self-reported medical diagnosis for all five conditions increased as wealth decreased, for example, in depression from 4% in the wealthiest quintile to 11% in the poorest (table 1). There was little variation between the waves for each of the five conditions (table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing participants at wave 5 (2010–2011) and self-reported medical diagnosis of angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis

| Whole sample, N | Angina, % | Cataract, % | Depression, % | Diabetes, % | Osteoarthritis, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 3886 | 8.2 | 13.4 | 5.4 | 13.3 | 19.8 |

| Female | 4843 | 6.3 | 20.4 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 32.9 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 50–59 | 1906 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 10.1 | 7.2 | 17.1 |

| 60–74 | 4766 | 5.8 | 14.5 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 28.1 |

| 75+ | 2057 | 15.0 | 36.6 | 2.9 | 15.0 | 34.1 |

| Wealth quintile* | ||||||

| 1 | 1716 | 3.4 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 21.5 |

| 2 | 1714 | 4.9 | 15.5 | 5.9 | 8.0 | 24.2 |

| 3 | 1723 | 6.6 | 20.1 | 5.7 | 11.3 | 25.7 |

| 4 | 1716 | 8.2 | 18.6 | 6.7 | 13.6 | 31.6 |

| 5 | 1715 | 12.9 | 19.2 | 11.5 | 16.7 | 33.1 |

| Missing | 145 | 5.5 | 9.7 | 4.8 | 9.7 | 20.0 |

| Total | 8729 | 7.2 | 17.3 | 6.7 | 11.1 | 27.1 |

*1=Wealthiest quintile, 5=least wealthy quintile.

Table 2.

Prevalence of illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment for angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis in four waves of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

| Angina N (%) |

Cataract N (%) |

Depression N (%) |

Diabetes N (%) |

Osteoarthritis N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness burden | |||||

| Wave 2 (2004–2005) | 397 (4.6) | 308 (3.5) | 2037 (23.4) | 160 (1.8) | 1106 (12.7) |

| Wave 3 (2006–2007) | 300 (3.6) | 317 (3.8) | 1929 (23.3) | NA | 917 (11.1) |

| Wave 4 (2008–2009) | 300 (3.1) | 331 (3.5) | 2049 (21.4) | 220 (2.3) | 1088 (11.4) |

| Wave 5 (2010–2011) | 254 (2.9) | 320 (3.7) | 1956 (22.4) | NA | 1046 (12.0) |

| Medical diagnosis | |||||

| Wave 2 (2004–2005) | 668 (7.6) | 1050 (12.1) | 402 (4.6) | 715 (8.2) | 1861 (21.4) |

| Wave 3 (2006–2007) | 591 (7.1) | 1294 (15.7) | 490 (5.9) | 935 (11.3) | 1952 (23.6) |

| Wave 4 (2008–2009) | 645 (6.7) | 1421 (14.8) | 601 (6.3) | 1215 (12.7) | 2262 (23.6) |

| Wave 5 (2010–2011) | 655 (7.5) | 1566 (17.9) | 602 (6.9) | 1413 (16.2) | 2416 (27.7) |

| Treatment | |||||

| Wave 2 (2004–2005) | 85 (1.0) | 535 (6.2) | 98 (1.1) | 552 (6.4) | 202 (2.3) |

| Wave 3 (2006–2007) | NA | 379 (4.9) | NA | 618 (7.5) | 141 (1.7) |

| Wave 4 (2008–2009) | NA | 444 (4.6) | 155 (1.6) | 671 (7.0) | 226 (2.4) |

| Wave 5 (2010–2011) | 88 (1.0) | 646 (7.4) | NA | 748 (8.6) | 208 (2.4) |

Total number of participants in each wave: wave 2: 8688; wave 3: 8268; wave 4: 9578; wave 5: 8729.

NA=data not available for that condition in that wave.

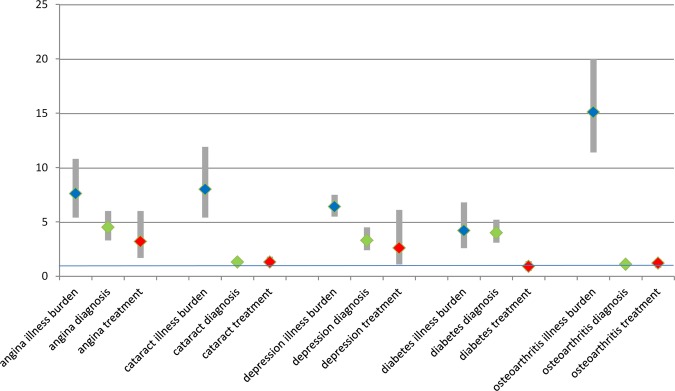

The hypothetically least wealthy participant had substantially higher odds than the hypothetically most wealthy of meeting the criteria for ‘illness burden’ from any of the five conditions at all four time points (overall OR ranged from 4.2 to 15.1; table 3). The least wealthy participant also had higher odds of diagnosis (ORs 1.1–4.5) and either no different or relatively small odds of treatment (ORs 0.9–2.6; table 3 and figure 1).

Table 3.

Illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment of angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis, comparing the least wealthy with the most wealthy: logistic regression

| Angina | Cataract | Depression | Diabetes | Osteoarthritis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORs (95% CI) | |||||

| Wave 2* (2004–2005) | |||||

| Illness burden | 5.6 (3.8 to 8.3) | 7.2 (4.5 to 11.5) | 5.1 (4.3 to 6.2) | 4.4 (2.5 to 8.0) | 11.0 (8.1 to 14.9) |

| Medical diagnosis | 2.9 (2.2 to 3.9) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 4.8 (3.3 to 7.0) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.2) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) |

| Treatment | 2.6 (1.2 to 5.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) | 0.6 (0.1 to 2.9) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) |

| Wave 3* (2006–2007) | |||||

| Illness burden | 8.7 (5.5 to 13.8) | 8.2 (5.1 to 13.1) | 6.9 (5.7 to 8.5) | 12.7 (9.1 to 17.8) | |

| Medical diagnosis | 4.9 (3.6 to 6.8) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) | 3.4 (2.6 to 4.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| Treatment | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.9) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.9) | ||

| Wave 4* (2008–2009) | |||||

| Illness burden | 6.7 (4.2 to 10.5) | 5.5 (3.6 to 8.6) | 5.9 (4.9 to 7.1) | 3.9 (2.4 to 6.4) | 14.0 (10.3 to 19.1) |

| Medical diagnosis | 4.3 (3.2 to 5.9) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 3.9 (3.1 to 5.1) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| Treatment | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) | 2.4 (1.0 to 5.9) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | |

| Wave 5* (2010–2011) | |||||

| Illness burden | 8.4 (5.1 to 13.7) | 6.2 (3.9 to 9.9) | 5.9 (4.8 to 7.1) | 16.0 (11.7 to 21.8) | |

| Medical diagnosis | 5.3 (3.9 to 7.3) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.8) | 4.3 (3.4 to 5.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| Treatment | 3.3 (1.5 to 7.3) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.6) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | |

| Overall† | |||||

| Illness burden | 7.6 (5.4 to 10.8) | 8.0 (5.4 to 11.9) | 6.4 (5.5 to 7.5) | 4.2 (2.6 to 6.8) | 15.1 (11.4 to 20.0) |

| Medical diagnosis | 4.5 (3.3 to 6.0) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 3.3 (2.4 to 4.5) | 4.0 (3.1 to 5.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

| Treatment | 3.2 (1.7 to 6.0) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8) | 2.6 (1.1 to 6.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6) |

Statistically significant ORs (where the 95% CIs do not include 1 before rounding to one decimal place) are shown in bold.

*ORs adjusted for age group and sex.

†ORs adjusted for age group, sex and unique participant identifier.

‡Analyses for osteoarthritis excluded those younger than 60 years, as data on osteoarthritis treatment were only collected in those aged 60 or over.25a

Figure 1.

Illness burden (in blue), self-reported medical diagnosis (in green) and treatment (in red) of angina, cataract, depression, diabetes and osteoarthritis, comparing the least wealthy with the most wealthy: Overall ORs (adjusted for age and sex) and 95% confidence bars: logistic regression.

For angina, the overall OR for meeting the criteria for ‘illness burden’ was 7.6, indicating that the hypothetically least wealthy individual was seven times more likely to have angina symptoms (defined by the Rose Angina scale) than the wealthiest. The OR for self-reported medical diagnosis was 4.5, suggesting that some less wealthy people with angina symptoms had not received a diagnosis of angina, as the expected OR for equitably distributed diagnosis would have been 7.6. The OR for treatment was 3.2, and again the expected ORs for equitably distributed treatment would have been 7.6. For depression, the overall OR for illness burden was 6.4, for medical diagnosis was 3.3 and for treatment was 2.6, again suggesting that some poorer people with symptoms of depression were less likely to have received a diagnosis or indicated healthcare, as the expected ORs for equitably distributed treatment would have been 6.4.

For diabetes, the overall OR for illness burden was 4.2 and 4.0 for diagnosis, suggesting that for diabetes, diagnosis was distributed equitably. However, the OR for treatment was 0.9 and not statistically significantly different from 1, again suggesting that some less wealthy people with medically diagnosed diabetes had not received treatment, as the expected OR for equitably distributed treatment would have been 4.2.

The subsidiary analysis calculated the OR of receiving a diagnosis by a subsequent wave only for those who had met the criteria for ‘illness burden’ for the relevant long-term condition in a previous wave, and then the likelihood of receiving treatment only for those who had received a medical diagnosis in a previous wave. The substantial inequalities in the illness burden of conditions by wealth are identical to table 3, as expected, and subsequently the numbers of eligible participants dwindle rapidly due to the nested nature of the analysis, with some wide CI and 9 out of 10 results not statistically significant (see online supplemental file 1).

Discussion

We found that while there were strong inverse associations between wealth and the burden of illness (based on validated scales, symptoms and biomarker) of a long-term condition, there were smaller or absent inequalities in receipt of self-reported medical diagnosis or treatment for the conditions considered. This suggests that the substantially higher illness burden in less wealthy participants was not matched by appropriately higher levels of diagnosis and treatment, and that equitable receipt of a medical diagnosis may have an important role in reducing inequalities in health.

ELSA is a unique single source of detailed data on socioeconomic status and health, and this is the first study to compare inequalities in illness burden, self-reported medical diagnosis and treatment of long-term conditions in a panel study over time. ELSA used robust measures of individual socioeconomic position, and standardised scales and blood biomarker to assess health status. This exploratory study has some limitations and the results should be interpreted with caution and tested in subsequent research. While standardised measures were used to estimate the illness burden of depression, angina and diabetes, symptoms alone were used for osteoarthritis and cataract, and the attributed symptoms were not specific for osteoarthritis and cataract. However, this lack of specificity is unlikely to vary with wealth, and so is not likely to be an important source of bias. Self-reported data may be a source of bias if self-report varies by factors other than objective health status, such as wealth or social experience. This is a recognised problem with some self-reported morbidity data, but is less of a problem with sensory assessment for pain, which is essentially self-perceived, and where self-report is the best means of assessment.26

We have not adjusted for health-related factors that are also more prevalent in poorer populations, such as smoking, obesity and comorbidity, because none of these are a reason for not making a diagnosis. Comorbid conditions are commoner in those with lower socioeconomic status, but there is no evidence that comorbidities make a new diagnosis less likely. On the contrary, a higher number of comorbid conditions in older people may be associated with higher quality of care.27 We found different patterns in different conditions, which fits with other research showing that wealth acts differently in different conditions, and for example, has no association with referral for postmenopausal bleeding.28 Major national policy interventions such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework payment for performance scheme in primary care29 have been associated with improved healthcare for included conditions such as angina and diabetes, more than for excluded conditions such osteoarthritis and poor vision.30–32

The serial cross-sectional analysis of four waves of ELSA included all eligible participants in each wave in order to maximise the sample size. This approach meant that some participants with a diagnosed condition would no longer have had symptoms or raised biomarkers, if they were being successfully treated. Examples would be diabetic participants whose blood sugar levels were being successfully controlled by treatment, and participants with successfully treated depression. We therefore checked our main results with the secondary (longitudinal) analysis, which assessed subsequent diagnosis in those had met the criteria for ‘illness burden’, and subsequent treatment in those with a medical diagnosis, but the number of participants who could be followed through the waves in this way was too small to allow meaningful conclusions to be drawn from the results.

Our results fit with previous findings that a greater proportion of people in deprived groups had Rose Angina, but there was no difference in the proportions receiving a general practitioner diagnosis of coronary heart disease.14 Care-seeking behaviour and patient preferences may differ with wealth. Given the same information, patients may want fewer medical interventions than their doctors recommend33 34 and pessimism about availability of treatment may make older people reluctant to seek help.35 Older people may view living with symptoms (such as pain, or emotional problems) as a normal part of ageing.36 The response of the primary care physician may also vary with the wealth of the patient. For example, the physician might be more likely to consider symptoms of breathlessness as a medical problem requiring a diagnosis, whereas aches and pains, poor vision and low mood might be considered part of the tapestry of life, or the natural ageing process. Comorbidity is more common in deprived populations, and may make diagnosis of all conditions harder for doctors within the constraints of a short consultation.37

At a system level, the results may be partially explained by wealthier people living in areas where there are more healthcare resources. Wennberg introduced the concept of ‘supply-sensitive care’ to describe how the quantity of healthcare resources allocated to a particular population was a major determinant of the frequency of use of health services by that population, and gives an example in which “a doubling of the supply of internists or cardiologists results in roughly a halving of the interval between repeat visits.”38 39 Where healthcare resources are relatively plentiful, patients with chronic diseases will consult more, use more diagnostic tests and be referred to hospital more. Further research could helpfully investigate whether those missing out on diagnosis are not accessing health services, or are seeing a doctor but not being diagnosed. The participants were selected to be nationally representative of the population of England, and so the findings are likely to be generalisable to England, but not to countries with different healthcare systems. If validated, our findings that inequalities in receipt of diagnoses are potential barriers to equitable healthcare for five common long-term conditions suggest that future policy interventions to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in healthcare should consider improving access to diagnosis as well as treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dave Stott and Amander Wellings, representatives of Public and Patient Involvement in Research (PPIRes), brought a helpful lay perspective to this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: NS contributed to the study design, oversaw data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the paper. NS is the guarantor. ACH undertook data preparation, analysis and interpretation, and contributed to drafting the paper. LTAM undertook data preparation and analysis. MOB and AC advised on statistical techniques. SHR, JC and IL advised on data analysis and interpretation. DM contributed to the study design and advised on data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to data interpretation and revised the paper critically.

Funding: This article presents independent research commissioned by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Health Services Research programme: HSR Project 10/2002/06—‘The dynamics of quality: a national panel study of evidence-based standards’. IL's work was supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula.

Competing interests: All authors had financial support from the National Institute for Health Research for the submitted work. DM had financial support from Age UK.

Ethics approval: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service: 09/H0505/124 and the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The ELSA data set and technical documentation are available from the UK Data Service at: http://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/catalogue?sn=5050.

References

- 1.Marmot M, Banks J, Blundell R, et al. Health, wealth and lifestyles of the older population in England: the 2002 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Börsch-Supan A, Brugiavini A, Jürges H, et al. Health, ageing and retirement in Europe. First results from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA), 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemingway H, Shipley M, Macfarlane P, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on coronary mortality in people with symptoms, electrocardiographic abnormalities, both or neither: the original Whitehall study 25year follow up. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:510–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social determinants of health: the solid facts. 2nd edn. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeown T. The role of medicine: dream, mirage or nemesis? 1st edn. London: Nuffield Principal Hospital Trust, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunker JP. The role of medical care in contributing to health improvements within societies. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1260–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watt G. The inverse care law today. Lancet 2002;360:252–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards HM, Reid ME, Watt GCM. Socioeconomic variations in responses to chest pain: qualitative study. BMJ 2002;324:1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner K, Chapple A. Barriers to referral in patients with angina: qualitative study. BMJ 1999;319:418–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger J, Mohr J. A fortunate man: the story of a country doctor. London: Penguin, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tod AM, Read C, Lacey A, et al. Barriers to uptake of services for coronary heart disease: qualitative. BMJ 2001;323:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaturvedi N, Ben Shlomo Y. From the surgery to the surgeon: does deprivation influence consultation and operation rates? Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:127–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahomed NN, Barrett JA, Katz JN, et al. Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards H, McConnachie A, Morrison C, et al. Social and gender variation in the prevalence, presentation and general practitioner provisional diagnosis of chest pain. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:714–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natcen Social Research. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) Wave One to Wave Five User Guide. 2012. http://www esds ac uk/doc/5050/mrdoc/pdf/5050_User_Guide_to_the_ELSA_Datasets_Waves_1_to_5 pdf (cited 28 Sep 2013)

- 16.Scholes S, Taylor R, Cheshire H, et al. Retirement, health and relationships of the older population in England: the 2004 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Technical Report P2808. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steel N, Melzer D, Gardener E, et al. Need for and receipt of hip and knee replacement—a national population survey. Rheumatology 2006;(45):1437–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL, et al. Prevalence of partial sight and blindness in people aged 75years and older in Britain: results from the MRC trial of assessment and management of older people in the community. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:795–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Congdon N, O'Colmain B, Klaver CCW, et al. Causes and prevalence of partial sight and blindness among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:477–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steel N, Melzer D, Shekelle PG, et al. Developing quality indicators for older adults: transfer from the USA to the UK is feasible. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:260–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S, et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with 32 quality indicators: national population survey of adults aged 50 or more in England. BMJ 2008;337:a957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagstaff A, Paci P, Van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:545–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bachmann MO, Eachus J, Hopper CD, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes complications, control, attitudes and health service use: a cross-sectional study. Diabet Med 2003; 20:921–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks J, Breeze E, Lessof C, et al. Retirement, health and relationships of the older population in England: the 2004 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (wave 2). London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheshire H, Hussey D, Medina J, et al. Financial circumstances, health and well-being of the older population in England: The 2008 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Wave 4. Technical Report. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25a.English Longitudinal Study of Ageing Wave Four Interview Questionnaire — 2008–2009. National Centre for Social Research, 2009. Available from: http://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/uploads/elsa/docs_w4/questionnaire_main.pdf (accessed 19 Oct 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sen A. Health: perception versus observation. BMJ 2002;324:860–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min LC, Reuben DB, MacLean CH, et al. Predictors of overall quality of care provided to vulnerable older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1705–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McBride D, Hardoon S, Walters K, et al. Explaining variation in referral from primary to secondary care: cohort study. BMJ 2010;341:c6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NHS Employers and the General Practitioners Committee. Quality and outcomes framework for 2012/13. Guidance for PCOs and practices. London: NHS Employers, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillam S, Steel N. The quality and outcomes framework: where next? BMJ 2013;346:f659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillam SJ, Siriwardena AN, Steel N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the quality and outcomes framework—a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:461–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steel N, Maisey S, Clark A, et al. Quality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:449–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steel N. Thresholds for taking antihypertensive drugs in different professional and lay groups: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2000;320:1446–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery AA, Fahey T. How do patients’ treatment preferences compare with those of clinicians? Qual Health Care 2001;10(Suppl 1):i39–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders C, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA. Unmet need for joint replacement: a qualitative investigation of barriers to treatment among individuals with severe pain and disability of the hip and knee. Rheumatology 2004;43:353–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray J, Banerjee S, Byng R, et al. Primary care professionals’ perceptions of depression in older people: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1363–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercer SW, Guthrie B, Furler J, et al. Multimorbidity and the inverse care law in primary care. BMJ 2012;344:e4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wennberg JE. Understanding geographic variations in health care delivery. N Engl J Med 1999;340:52–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ 2002;325:961–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.