Abstract

A mobile monitoring platform developed at the University of Washington Center for Clean Air Research (CCAR) measured 10 pollutant metrics (10 s measurements at an average speed of 22 km/hr) in two neighborhoods bordering a major interstate in Albuquerque, NM, USA from April 18-24 2012. 5 days of data sharing a common downwind orientation with respect to the roadway were analyzed. The aggregate results show a three-fold increase in black carbon (BC) concentrations within 10 meters of the edge of roadway, in addition to elevated nanoparticle concentration and particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter < 1 μm (PN1) concentrations. A 30% reduction in ozone concentration near the roadway was observed, anti-correlated with an increase in the oxides of nitrogen (NOx). In this study, the pollutants measured have been expanded to include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), particle size distribution (0.25-32 μm), and ultra-violet absorbing particulate matter (UVPM). The raster sampling scheme combined with spatial and temporal measurement alignment provide a measure of variability in the near roadway concentrations, and allow us to use a principal component analysis to identify multi-pollutant features and analyze their roadway influences.

Keywords: Traffic related air pollution, mobile monitoring, ozone, particulate matter, ultrafine particles, roadway gradient

1. INTRODUCTION

An appreciation for the complexity of pollutant dispersion and aging away from roadways in diverse urban environments has motivated innovation of new extensive monitoring designs, including mobile monitoring(Matte et al., 2013). Mobile monitoring platforms have been used to detect localized air pollution phenomena and to characterize their spatial and temporal extents. For example, mobile monitoring was used to detect dust carried by traffic out of industrial areas in the City of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (DeLuca et al., 2012), to identify neighborhoods in Los Angeles impacted by heavy-duty diesel traffic servicing the port(Kozawa et al., 2009), and to identify ultrafine particle (UFP) “clouds” in neighborhoods impacted by roadway configurations(Hu et al., 2012) and the airport(Hudda et al., 2013). Mobile monitoring has also been used to help identify urban areas of high wood smoke impact(Larson et al., 2007), and urban areas with high levels of traffic related BC(Larson et al., 2009).

Mobile monitoring has been implemented to characterize pollutant concentrations as a function of distance-to-roadway in a variety of scenarios including roadway type(Kozawa et al., 2009), the presence of topographical features(Hagler et al., 2010), meteorology(Kozawa et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2006), seasonal effects(Padro-Martinez et al., 2012), and time of day(Bukowiecki et al., 2002; Durant et al., 2010; Hagler et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2009; Massoli et al., 2012; Pattinson et al., 2014). As such, mobile monitoring presents the possibility to characterize spatio-temporal features of air pollutants under a variety of conditions. The results of such campaigns may improve predictive models for traffic-related air pollution, thereby advancing the science behind adverse health effects associated with distance to roadway.

Herein, we present a pilot study employing a mobile monitoring platform developed at the University of Washington Center for Clean Air Research (CCAR) to characterize near-roadway pollutant gradients. The sampling sites were residential neighborhood streets adjacent to a major interstate in a location with flat topography and no high-rise buildings resulting in a distinct line source with few obstructions while remaining in an urban setting. The platform recorded spatially and temporally aligned 10 s measurements of 10 different pollutant metrics, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, particle size distribution (0.25-32 μm), and ultra-violet absorbing particulate matter (UVPM). In this paper we assess the correspondence of our single pollutant near roadway gradients with those previously reported, and use principal component analysis to reveal multi-pollutant features and analyze their spatial relationship to the roadway.

2. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

2.1 Sampling Sites

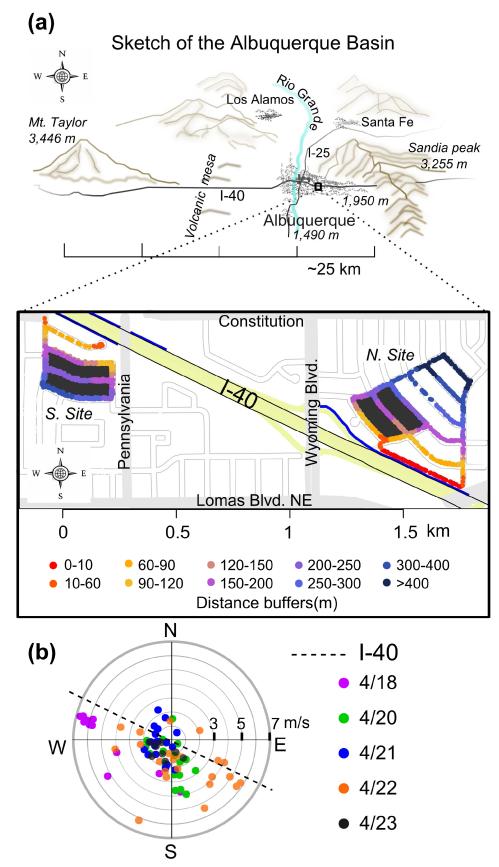

Monitoring took place along the I-40 corridor in Albuquerque, NM on the Eastern side of I-25 as depicted in Figure 1a. The city of Albuquerque sits in a basin defined by the Sandia Mountain range to the East and a volcanic mesa to the West. The Rio Grande River meanders from North to South along the bottom of this shallow basin. These features result in typical winds with a westerly component. The section of I-40 chosen for this study consisted of three westbound lanes and four eastbound lanes at the time of monitoring. Figure 1a includes a map of the two monitoring “sites” situated on the North and South sides of I-40. A site is defined by a collection of road segments within a selected area (see figure 1). A highway off ramp was adjacent to the North site, but not the South site. The monitoring sites were in residential neighborhoods containing one- and two-story houses. We anticipated the flat topography and absence of high-rise buildings at these sites would simplify visualization and interpretation of near-roadway pollutant gradients relative to more complex locations.

Figure 1.

a) Sketch of Albuquerque and surrounding area, and map of the sample sites. Sound barriers are denoted with a solid blue line. Colored dots represent GPS locations of measurements from the 5 days data analyzed. Color gradient trends red to blue with increased distance from edge of roadway (black outline of I-40). The route consisted of the roads surrounding the shaded blocks for the dates 4/18-4/21. b) Wind rose of 10 min average wind direction (direction of origin) and speed (m/s) as reported by the Albuquerque International Sunport airport (7.8 km south of the monitoring sites) from sampling times of a given day. Sampling days are denoted by color; 4/18/2012 (pink), 4/20 (green), 4/21 (blue), 4/22 (orange), 4/23 (black). I-40’s direction is denoted as the dashed black line.

Figure 1 illustrates the sampling sites are behind sound barriers at the edge of roadway. These structures have the potential to alter pollutant levels adjacent to the roadway depending upon wind direction and speed, since these combine to create a variety of eddy currents, as has been established by others(Baldauf et al., 2008; Bowker et al., 2007; Finn et al., 2010; Hagler et al., 2011; Ning et al., 2010; Steffens et al., 2013). The sampling sites in this study are both completely behind the sound barriers, and are therefore insufficient for a 2-dimensional analysis of barrier influences. Instead, we reduced our data to one spatial dimension as others have done (Massoli et al., 2012).

2.2 Monitoring Platform

2.2.1 Instrumentation

The mobile monitoring platform consisted of a 2012 gasoline powered Ford Escape with two sampling inlets mounted on the roof rack on the driver’s side of the vehicle in forward position (see Figure S1 in supplemental) leading to gaseous and particle measurement instrumentation inside. The inlet lines were positioned above the vehicle boundary layer, and entered the vehicle through the otherwise sealed left rear window where they were connected to the instruments. The sample inlet is designed to provide isokinetic sampling at a speed of 35 km/hr, allowing for repeated measures of near-road gradients in a short amount of time. The absence of an additional pollutant signal while stopped along the sampling route verified a negligible contribution from the mobile monitor vehicle’s exhaust to the measurements.

One sample inlet was made from stainless steel and copper to minimize corrosion as well as particle deposition due to electrostatic interactions with the tubing. The inlet was outfitted with a water trap consisting of a small plastic bottle to check for accumulated moisture (remained dry this campaign). The particle inlet meets a Y junction, where the GRIMM particle spectrometer draws air through one side, while the nephelometer blower draws air past the Y at a rate of 7 L/min through a stainless steel manifold into the nephelometer. The manifold consists of an electrical junction box that had its interior paint sandblasted away; it includes eight ports for instrumentation. This campaign used three ports for the micro-aethelometer, P-Track, and EcoChem. Temperature/relative humidity and CO2 sensors were placed inside the manifold.

The second inlet made of Teflon tubing branched to the analyzers for NO, NOx, ozone, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Each device pulled their own sample with a total gas inlet flow of 5 L/min at the Teflon tube. Instrumentation was powered by 120 volt AC generated by inverters that transformed the 12 V DC source. Two external 12 V batteries in parallel and the vehicle’s internal accessory power system provided DC power.

A GPS mounted on the roof of the vehicle recorded position and speed. A diagram of the monitoring platform is provided in Figure S1 in supplemental. The instruments and their measurement ranges are summarized Table 1.

Table 1. Mobile Monitoring Platform Instruments.

| Parameter | Instrument | Manufacturer | Measurement Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerosol Light Scattering | Nephelometer | Radiance Research | 0 - 10−3 m−1 |

|

Particle-bound Polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) |

PAS 2000CE | EcoChem | 0- 4000 ng/m3 |

|

PN1 number concentration (0.05

−1 μm) a) |

PTRAK 8525, with particle diffusion screen |

TSI | 0 −5 × 105 particles/cm3 |

| Black Carbon (BC), UVPM | micro-Aethalometer AE52† |

AethLabs | 0-1 mg/m3 |

|

Particle concentration per size

fraction |

Spectrometer 1.109 | GRIMM | 31 bins, 0.25 - 32 μm; 1-2×106 N/l |

|

Nanoparticle concentration and

mean diameter |

NanoCheck 1.320 | GRIMM | 25 nm - 400 nm; 0- 4×106 N/cm3 |

| NO | NO Model 410 | 2B Technologies | 0 - 2000 ppb |

| NOx, NO2 by Difference | NO Model 410, Converter #401 |

2B Technologies | 0 - 2000 ppb |

| Ozone | Ozone Analyzer 3.02 P-A | Optec | 0 to 255 ppb |

| CO2 | SenseAir CO2 K-30-FS sensor |

CO2Meter.com | 0 - 5,000 ppm (vol.) |

| Temperature & RH | Precon HS-2000 | Kele Precision Manufacturing | |

|

Positioning & Real-Time

Tracking |

GPS Receiver BU-353 | US GlobalSat |

Normal P-trak lower size limit is 0.02 μm, the total number count given by nanocheck the screen provides additional independent size resolved count data.

MicroAeth® Model AE51, custom modified by AethLabs for dual wavelength acquisition

2.2.2 Data Acquisition

Data was written to a customized Dell Latitude E6520 laptop computer featuring an intel quad core i7 processor and 8 GB of RAM for managing data streaming, and a 256 GB solid state hard drive for operation in rugged conditions. Instrumentation was interfaced using either 1) An instrument’s USB interface (Precon T/RH, Sensair CO2, GPS, Webcam, GRIMM, micro-Aethalometer) 2) the instrument’s RS-232 serial interface and a National Instruments serial interface for USB (NI USB 232) (P-Trak, 2B Tech NO/NOx), or 3) an analog signal employing the National Instruments CompactDAQ system (Nephelometer, Optetc, EcoChem). In addition, some instruments internally logged data that was saved in separate files. For instance, the nephelometer’s internally logged data was preferred as the laptop-acquired analog signal suffered from interference issues. Data synchronization and logging was performed using a Windows 7 Pro operating system running LabVIEW 2010 with DAQmx 9.4 and NI serial 3.8 instrument drivers. In order to reconcile data reporting rates for each instrument as well as lag times for queried data, a 30 s “last in, first out” data buffer was created in LabVIEW for each instrument. The buffer ensured the newest possible data was written and data older than 30 s was removed from the buffer. A 10 s average was reported from the newest data in the buffer if instruments reported faster than 10 s.

2.3 Sampling times and methods

Monitoring took place in the afternoons inclusive of the dates 4/18/2012 - 4/24/2012. The two monitoring sites were driven at a speed of 6.0 (± 2.6) m/s. A site visit consisted of the continuous data collected at one of the two sites before leaving to sample at the other location. During each visit to a sampling site, the route was driven 4 times in a raster pattern in alternating directions of travel to control for directionality of sampling (see figure 2). For the first three days (18th-21st) the sampling route was limited to the roads encompassing two blocks at each site (shaded regions in Figure 1), for the 22nd - 24rd the route was expanded as indicated by the data density. The nearest roadway segment at the north site was not always sampled due to traffic control measures. The monitoring platform made ~1-2 visits to each site per sampling day (see Table S1 in supplemental materials).

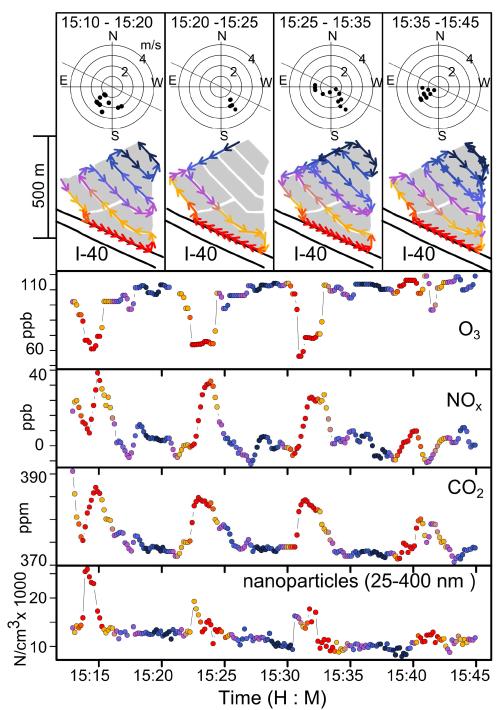

Figure 2.

Selected time series for background-corrected ozone, NOx, CO2, and nanoparticle concentration from 4/23/2012 during the period of 15:12-15:45 local time of a North site visit; top panel shows direction of travel of each traverse. As the distance to roadway decreases (blue to red transition) an increase in NOx and nanoparticle concentration is observed, coinciding with a decrease in ozone concentrations. Color legend is in figure 1.

2.4 Data Quality Control

Instruments were calibrated for flow, zero, and span in the lab before shipping to Albuquerque. In-field calibration checks for zero and span were performed periodically between measurement runs. The Optec ozone monitor was recalibrated in the field on 4/17/2012 and 4/19/2012, and the nephelometer was recalibrated on 4/17/2012.

Data processing was performed using custom programs written in R language. The LabVIEW file was merged with internally logged instrument data files and temporally aligned to the closest LabVIEW entry. Automated flagging routines censored data corresponding to instrument error codes, instruments operating out of specified parameters, or data otherwise missing (instrument rebooted itself, lost power, etc.). The time series for each pollutant were then manually inspected for anomalies and cross checked with field technician notes.

2.5 Data Processing

2.5.1 Wind and Traffic Data

The Albuquerque International Sunport airport weather station (KABQ), located ~7.8 km south of the sites, provided 1 minute land station data (NOAA National Climatic Data Center, 2012). Wind speed and direction were converted to 5 minute vector averages. Airport wind direction data demonstrated excellent agreement with a Weather Underground (Hoffmantown KNMALBUQ110, 35.11°N, 106.54°W) station in close proximity (1.6 km north) to the monitoring sites.

Hourly traffic count data was obtained from the New Mexico Department of Transportation for Bernalillo County site 2035 (intersection of I-40 and Coors Blvd)(New Mexico Department of Transportation).

2.5.2 Data Selection Process

The vetted data set was divided into two subsets based upon wind direction during the daily monitoring windows. For five of the seven monitoring days, the North side of I-40 was downwind (4/18 and 4/20-4/23), data from these days were analyzed. Owing to the smaller sample size of the two opposing wind direction days (and some missingness) these days were not analyzed. The 10-minute averaged wind speed and direction for the 5 days included in the analysis are given in Figure 1b. Table S1 (see supplemental material) summarizes the sampling times, temperature, relative humidity, and average hourly traffic counts pertaining to the subset of days included in the data analysis.

2.5.3 GIS Data Operations

To estimate the location of each measurement relative to the roadway, the edge of the roadway was defined by tracing the outline of I-40 (both North and South edges) in Google Earth and exporting the set of vertices corresponding to the respective paths as a KML file. The KML file was converted to CSV using an online tool(Zonum Solutions, 2013). All lat/long pairs for the GPS-tagged pollutant data and roadway vertices were converted to a Cartesian reference plane using a pair of co-latitude reference points with the function “spDistsN1” from the R package “sp” (Pebesma and Bivand, 2005; Roger S. Bivand, 2013). The perpendicular distance to the spatial line object created from the edge of roadway data was calculated for individual measurements using the function “gDistance” from the R package “rgeos”(Bivand and Rundel, 2013).

2.5.4 Particle Size Distribution

The 31 GRIMM particle size channels were reduced to three categories for simplicity: 0.25 - 1 μm, 1 - 2.5 μm, and 3 - 32 μm. These categories correspond to the fine particle mode, the intermodal range, and the coarse particle mode, respectively.

2.5.5 Background Correction and Peak Removal

PN1 number (P-Trak) and nanoparticle concentrations (NanoCheck) contained a time component during two monitoring days where the background concentrations changed substantially for return visits separated by an hour or more (see Table S1 in supplemental materials). Since we were interested in the near roadway relationship between pollutants we corrected for changes in the background concentrations as follows:

| (Equation 1) |

where ci is a 10-second average measurement for a given pollutant, and a visit refers to sampling at either the north or south site. We defined background to be distances greater than 250 m from the edge of roadway, a choice made based upon the smaller of the two sampling areas indicated in figure 1. Background subtraction, unlike normalization by division, preserves the variance in the concentrations of pollutants during each site visit. A limitation of aligning the median background concentration for all 17 site visits (North and South combined) is negating the relationship between the concentrations at the upwind and downwind sites on any given sampling visit. It is possible under some meteorological conditions roadway derived pollutants remain elevated above background at distances greater than 500 m from the edge of the roadway; however our results indicate pollutant concentrations decayed to background levels by 200-300m for the days analyzed.

After background correction, data in excess of 3 standard deviations of the mean were censored for each pollutant (except nanoparticle diameter) to remove data corresponding to discrete vehicle exhaust plumes before further analysis. Peaks did not influence the medians or interquartile range calculated below; however, they distort estimations of the modeled mean on the natural scale. Peaks also affect to some extent the principal component analysis which detects variability.

2.5 Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using custom scripts written in R language version 3.00 (R Core Team, 2013).

2.5.1 Single Pollutant Analysis

Data were divided into 10 distance-to-edge of road categories for the North site and 7 for the South site; category boundaries were chosen to optimize data density. A description of the category boundaries as well as a figure illustrating the data density (Supplemental figure S2) are available in the supplemental materials. For each category, the median distance to roadway was computed along with the medians and interquartile range for each pollutant.

The mean pollutant concentrations were modeled without categories using a generalized additive model employing a thin-plate spline smooth(Wood, 2003). When appropriate, the data were log transformed to estimate the geometric mean and its standard errors instead of the arithmetic mean. The exception to this was NOx, Grimm particle data, and BC which were modeled on the natural scale owing to zeros in the data set, and negative values in the case of NOx. Modeling was performed using the function “gam” from the package “mgcv”(Wood, 2011), smoothing parameters were adjusted from automated procedures as needed to reduce localized fitting.

The modeled mean concentrations were normalized to the background concentration from Equation 1. The normalized mean concentrations presented in figure 4a were calculated as:

| (Equation 2) |

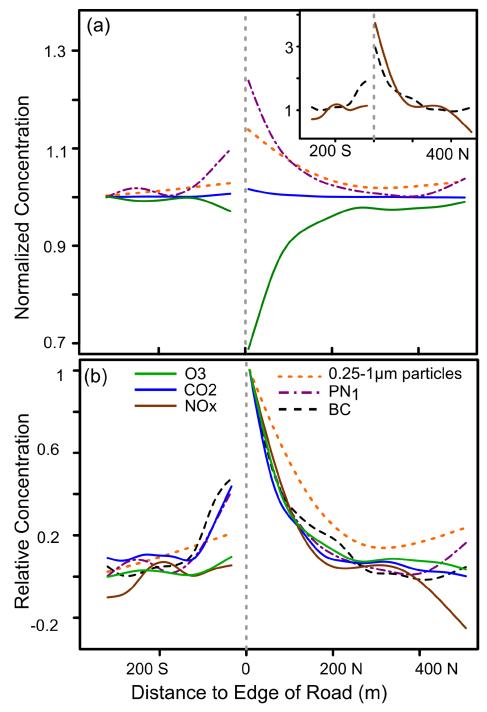

Figure 4.

a) Modeled pollutant concentrations from figure 4 normalized by the estimated median background concentration (Equation 2). b) Modeled pollutant concentrations from figure 4, background subtracted then normalized by the nearest to roadway prediction (Equation 3). For ozone, this results in a sign change causing it to appear at a greater concentration near the roadway. Legend in figure 4b also applies to figure 4a.

The concentrations relative to the edge of roadway were calculated by first subtracting the background concentration, then dividing by the nearest to roadway estimate of the concentration (Equations 3a and 3b), and are presented in figure 4b.

| Equation 3a |

| Equation 3b |

2.5.2 Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis was performed on complete observations including all pollutants (see table 1) using the function “principal” from the R package “psych” (2014, version 1.4.5). The nephelometer data were excluded from this analysis owing to periodic missing values associated with an internal timing setting. A scree plot was examined for all PCs, and four PCs were selected based upon eigenvalues greater than ~1. Four components accounted for 62 % of the variance. Varimax rotation, which preserves orthoganality while improving interpretability by further diminishing minor loadings in the principal components, was subsequently applied to the four PCs and are reported here.

3. RESULTS

Consistent with prior reports, we find 5-minute wind direction and speed reliably defines the directionality of pollutant gradients away from the roadway; this time scale is preferable to hourly averages which can over average wind direction(Zhu et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2006). The wind for the 5 days (4/18, 4/20-23) was intermittent as can be seen in the 10-minute average wind speed and direction data shown in the wind rose in Figure 1b. The wind rose illustrates ~1 hour of data across 5 days is low speed and possibly originating from the north; however, omitting these data did not change the results. A broad range of wind directions and wind speeds were recorded over the 5 days of sampling times.

Ambient pollutant concentrations captured at the nearby AQS monitoring station (6 km NW of the sites) during monitoring time are provided in Table S1 in supplemental materials (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (AQS) Data Mart, 2012). As a comparison, the background concentrations determined from each of the site visits on the 5 monitoring days are also summarized in Table S1.

Our background NOx measurements were lower than the AQS data on aggregate, which may be due to failures of the ozone scrubber in the 2B Tech model 410 analyzers. Consequently, we expect variations in ambient ozone will partially interfere with the NO and, to a lesser extent NOx measurements. For this reason NO data (which exhibited more extreme negative values) were excluded from this analysis. Interference from VOCs can cause loss of accuracy for the 2B Tech instruments as the ozone scrubber when operating properly has an ancillary effect of reducing VOC interference.

The time series data in figure 2 shows four traverses from a single visit to the north site. During these four traverses pollutant concentrations were relatively stable at distances greater than 100 meters from the edge of roadway, and increased (or decreased in the case of ozone) within 50 meters of the roadway. On the final traverse, the pollutant concentrations show little variation with distance to roadway, consistent with either intermittent wind or fluctuations in vehicle densities.

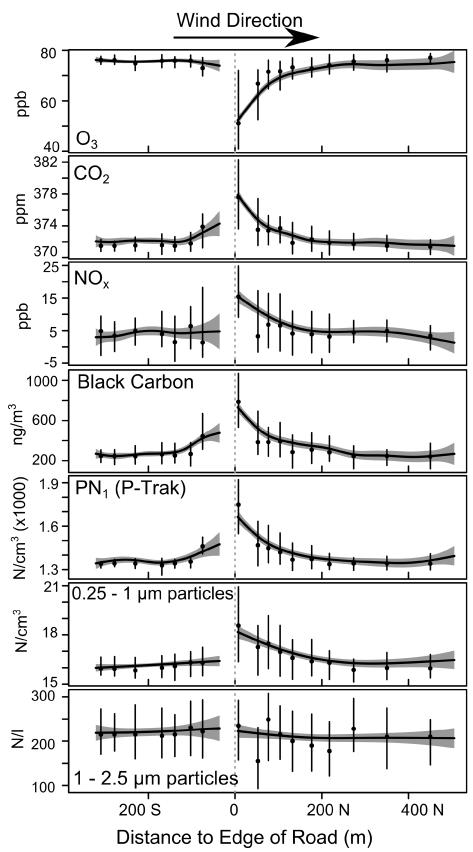

The spatial relationship of pollutant concentrations with absolute distance to roadway were interrogated two ways. First we categorized the data based upon their distance to the edge of roadway, and calculated the category-specific median, 25th and 75th quartiles. These statistics are presented in figure 3, wherein the x-axis value is the median distance to edge of roadway for each category. The south site had limited near-roadway access (see figure 1); the nearest roadway location is 35 m from the edge of roadway for the South site versus 7 m for the North site. In the second analysis the mean concentrations were modeled as a function of distance to edge of roadway without categorization using a general additive model employing a thin plate spline smooth(Wood, 2003). The upwind and downwind data were modeled separately.

Figure 3.

Pollutant concentrations measurements categorized by distance from edge of roadway. Wind direction indicated by arrow at top (see figure 1b for detailed wind direction). Filled circles are the median pollutant concentrations and vertical bars indicate the interquartile range. Dashed gray line indicates the edge of roadway. The black trend line is a general additive model employing a thin plate spline (see figure S2 in supplemental for fit to raw data). The 95% confidence interval on the modeled concentration mean is given as the gray shaded area. Plots for additional pollutants are included as Figure S3 in the Supplementary Information.

As shown in Figure 3, we observe an increase in CO2, BC, fine particle number concentrations, and NOx at the downwind edge of roadway, as well as depletion of ozone at the edge of roadway. PN1 number concentration (P-Trak) data exhibit lower counts because a diffusion screen removes particles <50 nm. Particle counts with diameter >1 μm did not significantly increase at the roadway consistent with prior reports(Karner et al., 2010; Massoli et al., 2012). A comparison of roadway influences on pollutant concentrations is made in figures 4a and 4b, where the predicted pollutant concentrations are normalized to the background and near roadway values, respectively.

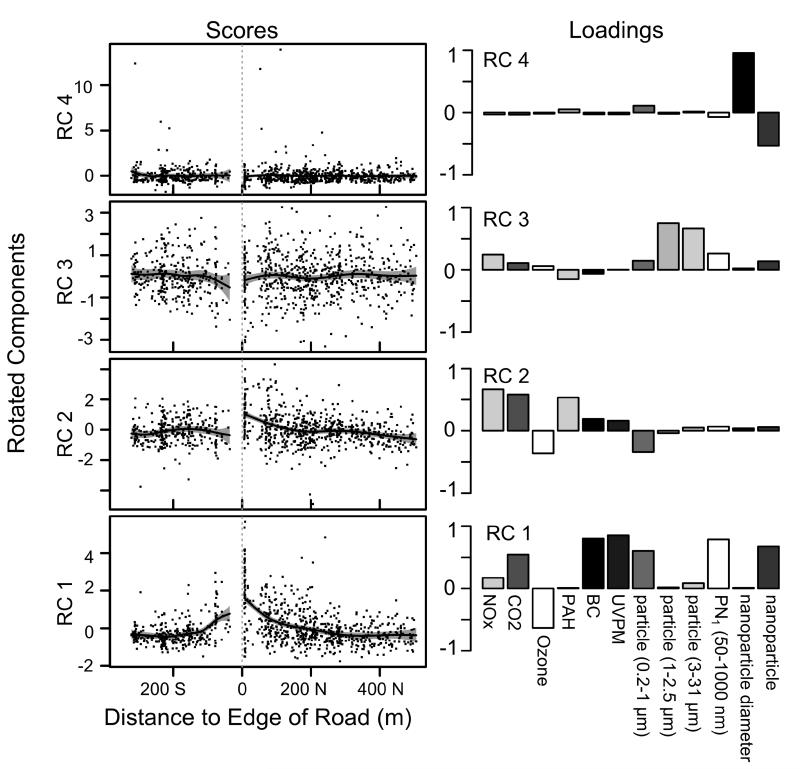

Figure 5 shows the first 4 Varimax rotated principal components, and their scores as a function of distance to roadway. The first component (RC1) explains 30% of the variance, and the increased scores at the edge of roadway indicate the pollutants with substantial loadings in RC1 are elevated (or depleted in the case of ozone). A distance to roadway relationship is also observed for RC2 but not RC3 and RC4.

Figure 5.

Varimax rotated principal components computed from complete 10 second measurements. Left panel is a plot of component scores for the 10 second measurements plotted with distance to edge of roadway, the right panel is the pollutant loadings for the first 4 rotated components. Four components explain 62% of the variance with the following breakdown: RC1, 30%; RC2, 12%; RC3, 10%; and RC4 10%.

4. DISCUSSION

Mobile measurements of near roadway pollutant gradients have been successfully demonstrated previously at speeds comparable to our mobile platform (4-10 m/s)(Durant et al., 2010; Massoli et al., 2012; Padro-Martinez et al., 2012). We are interested in determining if a mobile platform could detect the roadway source during multiple fast passes through the sampling sites. Sampling of sites at shorter durations results in a sparse spatial data set per-pass; however, this scheme allows sampling over many more sites in a city per sampling campaign. If rapid-pass sampling provides meaningful summaries compared to extensive sampling schemes, then the uses for mobile monitoring to characterize spatial-temporal variability over a larger scale can be expanded.

Figure 2 illustrates the gaseous, and nanoparticle pollutants are indeed manifesting roadway influences as detected by our monitoring platform. Each traverse of the site roadways captures one eventuality of the near roadway concentrations which can vary between traverses. Variability may be due to changes in the source strength (i.e. number of vehicles), or variable wind speed and direction. Combining data over multiple days (~36 individual traverses of each site) generates plausible “average” afternoon pollutant profiles of the I-40 roadway for Southerly winds as illustrated in figure 3. The variability noted in figure 2 is even more apparent in the interquartile ranges of pollutant concentrations depicted in figure 3. The interquartile range decreases with increased distance to roadway, indicating a stable background concentration has been reached. Figure 3 shows a slight increase in the modeled mean of pollutant concentrations for PN1 number concentration, BC, and CO2 upwind of the roadway. This phenomena is discussed below.

The ozone depletion near the edge of roadway on the down-wind side (see figure 3) is well defined compared to those summarized by Karner et al, who concluded the ~30% depletion of ozone at the edge of roadway was not statistically significant(Karner et al., 2010). Our results show a return to background by 200 m consistent the findings using stationary passive monitors. Unlike stationary monitors, ozone measurements obtained by multiple pass mobile sampling provide a measure of variability indicative of capturing periods of pronounced ozone depletion during periods of heavy traffic as well as of modest or no depletion. These details are obscured in integrative sampling schemes that average over long periods of time. Near roadway ozone concentrations were recently measured with a different mobile platform, the Aerodyne Reasearch Inc. mobile laboratory (Durant et al., 2010; Massoli et al., 2012). The authors reported a modest decrease in ozone near roadway, although ambient ozone concentrations were much lower than in our study. One explanation for the difference compared to Durant et al. may be a difference in instrumentation. The Aerodyne mobile platform was equipped with a UV-Vis absorption ozone monitor (model 205, 2B-Tech), whereas the Optec monitor on our platform operates using a chemiluminescence signal produced upon reaction of ozone with a proprietary substrate resulting in emission at 560 nm. Unlike UV-Vis methods which can be prone to interference with hydrocarbon signals (Dunlea et al., 2006; Spicer et al., 2010), the Optec instrument exhibited no hydrocarbon interference during EPA protocol testing (ETV Advanced Monitoring Systems Center (U.S.), 2008).

Figure 4a shows the modeled mean pollutant concentrations normalized by the background concentration derived from all 5 days (see equation 2). Figure 4a allows us to compare our results to those summarized by Karner et al. who report on the relative concentrations of pollutants with respect to background. We find a three-fold increase in BC near the edge of roadway, consistent with Massoli et al.(Massoli et al., 2012), whereas Karner et. al report a 2 fold increase in elemental carbon. A 30% decrease in ozone was detected near roadway as was also reported by Karner at al. We find a 5 fold increase in NOx, whereas Karner et al. report a range of 1.8-3.3 increase for the oxides of nitrogen. One cause for the discrepancy in NOx may be the lower background levels measured in this campaign owing to failures of the ozone scrubber previously mentioned. A modest increase in PN1 concentration is observed, consistent with Karner et al.’s findings, as well as more recent mobile monitoring results reported by Massoli et al..(Massoli et al., 2012) Figure 4b show the relative modeled concentrations obtained by background subtraction and subsequent division by the nearest to roadway value (equation 3). Figure 4b illustrates the relative decay of pollutant concentrations for the gaseous and particulate species most impacted by the roadway. Karner et al. reports a 50% drop in NOx, and elemental carbon between 100-150 m from edge of roadway. (Karner et al., 2010) Our results indicate a 50% decrease in pollutant concentrations by 100 m from the edge of roadway for most pollutants under stable afternoon conditions, with slower return to background observed fine particle concentration.

The similarity of pollutant concentration decay profiles in figure 4b suggest multi-pollutant correlations, which we analyze using principal component analysis. The first component (RC1) with high loadings in nanoparticles, PN1, and BC and NOx is indicative of heavy duty diesel emissions. The second component (RC2) is comprised of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), NOx and CO2, consistent with general traffic as most of the CO2 is emitted by light duty vehicles. NOx is split between RC1 and RC2 consistent with emission inventories of light duty and heavy duty diesel emissions. The scores of RC1 decay within 100 meters of the roadway, whereas RC2 demonstrates a slow continual decay from the roadway. RC1 has a significant increase in scores near roadway upwind. Both RC1 and RC2 contain substantial loadings of NOx and exhibit decaying scores with increased distance downwind. This indicates that the elevated scores upwind for RC1 are not due to prevailing wind direction. The time series for RC1 (see figure S4 in supplemental) revealed this upwind feature occurred for multiple site visits on the 23rd and 24th. We propose that the associated turbulent wake induced by passing heavy duty vehicles could produce upwind impacts near the roadway.

The third component (RC3) is comprised of larger diameter particle concentrations and low loadings of gaseous pollutants; this component appears to have no variation with distance to roadway and may be consistent with an urban background. Finally, the last component is dominated by nanoparticle diameter, which demonstrates no correlation with other pollutants, except for nanoparticle concentration, where large diameters correspond to lower number concentration. This feature may be indicative of physical aging of the nanoparticles.

4.1 Conclusions

Meaningful single and multi-pollutant gradients from an isolated roadway source were captured by the mobile monitoring platform. The single pollutant gradients reported are consistent with previous studies as summarized by Karner et al. (2010). Unlike stationary monitors, characterization of the spread in the pollutant concentrations with distance to roadways provides additional detail about pollutant dispersion and source variability. Synchronous data collection allowed for principal component analysis, which yielded two multi-pollutant components that have distinct distance to roadway gradients in their scores. An additional component indicated evidence for physical aging of nanoparticles near the roadway. Elevated pollutant concentrations upwind of the roadway were observed, consistent with significant impacts from the turbulent wake of passing trucks.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This publication was made possible by USEPA grant (RD-83479601-0). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USEPA. Further, USEPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication. Additional support provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES015459, P30ES007033). This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsoring agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Table S1 contains a summary of the AQS site pollutant concentrations, traffic data, and mobile monitoring data. Figure S1 is a diagram of the mobile monitor. Figure S2 illustrates all pollutant measurements overlaid with modeled concentration. Figure S3, illustrates medians and IQR for the full suite of pollutants measured on the CCAR platform overlaid with modeled concentration. Figure S4 is an ordered time series of RC1 colored by distance to roadway for the south site (upwind) only.

REFERENCES

- Baldauf R, Thoma E, Khlystov A, Isakov V, Bowker G, Long T, Snow R. Impacts of noise barriers on near-road air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42(32):7502–7507. [Google Scholar]

- Bivand R, Rundel C. rgeos: Interface to Geometry Engine - Open Source (GEOS), R package version 0.3-2. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Bowker GE, Baldauf R, Isakov V, Khlystov A, Petersen W. The effects of roadside structures on the transport and dispersion of ultrafine particles from highways. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41(37):8128–8139. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowiecki N, Dommen J, Prevot ASH, Richter R, Weingartner E, Baltensperger U. A mobile pollutant measurement laboratory-measuring gas phase and aerosol ambient concentrations with high spatial and temporal resolution. Atmos. Environ. 2002;36(36-37):5569–5579. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca PF, Corr D, Wallace J, Kanaroglou P. Effective mitigation efforts to reduce road dust near industrial sites: Assessment by mobile pollution surveys. J. Environ. Manage. 2012;98:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlea EJ, Herndon SC, Nelson DD, Volkamer RM, Lamb BK, Allwine EJ, Grutter M, Ramos Villegas CR, Marquez C, Blanco S, Cardenas B, Kolb CE, Molina LT, Molina MJ. Technical note: Evaluation of standard ultraviolet absorption ozone monitors in a polluted urban environment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006;6:3163–3180. [Google Scholar]

- Durant JL, Ash CA, Wood EC, Herndon SC, Jayne JT, Knighton WB, Canagaratna MR, Trull JB, Brugge D, Zamore W, Kolb CE. Short-term variation in near-highway air pollutant gradients on a winter morning. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10(17):8341–8352. doi: 10.5194/acpd-10-5599-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ETV Advanced Monitoring Systems Center (U.S.), H., P., Battelle Memorial Institute., & United States. Environmental Protection Agency . JSC OPTEC 3.02 P-A chemiluminescent ozone analyzer. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Finn D, Clawson KL, Carter RG, Rich JD, Eckman RM, Perry SG, Isakov V, Heist DK. Tracer studies to characterize the effects of roadside noise barriers on near-road pollutant dispersion under varying atmospheric stability conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44(2):204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hagler GSW, Tang W, Freeman MJ, Heist DK, Perry SG, Vette AF. Model evaluation of roadside barrier impact on near-road air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2011;45(15):2522–2530. [Google Scholar]

- Hagler GSW, Thoma ED, Baldauf RW. High-Resolution Mobile Monitoring of Carbon Monoxide and Ultrafine Particle Concentrations in a Near-Road Environment. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2010;60(3):328–336. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.60.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Fruin S, Kozawa K, Mara S, Paulson SE, Winer AM. A wide area of air pollutant impact downwind of a freeway during pre-sunrise hours. Atmos. Environ. 2009;43(16):2541–2549. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Paulson SE, Fruin S, Kozawa K, Mara S, Winer AM. Observation of elevated air pollutant concentrations in a residential neighborhood of Los Angeles California using a mobile platform. Atmos. Environ. 2012;51:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudda N, Fruin S, Delfino RJ, Sioutas C. Efficient determination of vehicle emission factors by fuel use category using on-road measurements: downward trends on Los Angeles freight corridor I-710. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2013;13(1):347–357. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-347-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner AA, Eisinger DS, Niemeier DA. Near-Roadway Air Quality: Synthesizing the Findings from Real-World Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(14):5334–5344. doi: 10.1021/es100008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozawa KH, Fruin SA, Winer AM. Near-road air pollution impacts of goods movement in communities adjacent to the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Atmos. Environ. 2009;43(18):2960–2970. [Google Scholar]

- Kozawa KH, Winer AM, Fruin SA. Ultrafine particle size distributions near freeways: Effects of differing wind directions on exposure. Atmos. Environ. 2012;63:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson T, Henderson SB, Brauer M. Mobile Monitoring of Particle Light Absorption Coefficient in an Urban Area as a Basis for Land Use Regression. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(13):4672–4678. doi: 10.1021/es803068e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson T, Su J, Baribeau A-M, Buzzelli M, Setton E, Brauer M. A Spatial Model of Urban Winter Woodsmoke Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41(7):2429–2436. doi: 10.1021/es0614060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoli P, Fortner EC, Canagaratna MR, Williams LR, Zhang Q, Sun Y, Schwab JJ, Trimborn A, Onasch TB, Demerjian KL, Kolb CE, Worsnop DR, Jayne JT. Pollution Gradients and Chemical Characterization of Particulate Matter from Vehicular Traffic near Major Roadways: Results from the 2009 Queens College Air Quality Study in NYC. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2012;46(11):1201–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Matte TD, Ross Z, Kheirbek I, Eisl H, Johnson S, Gorczynski JE, Kass D, Markowitz S, Pezeshki G, Clougherty JE. Monitoring intraurban spatial patterns of multiple combustion air pollutants in New York City: Design and implementation. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2013;23(3):223–231. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Mexico Department of Transportation . Roadway, Monthly Hourly Volume for April 2012. 2012. http://www.dot.state.nm.us/en/Planning.html#Data. [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, Hudda N, Daher N, Kam W, Herner J, Kozawa K, Mara S, Sioutas C. Impact of roadside noise barriers on particle size distributions and pollutants concentrations near freeways. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44(26):3118–3127. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA National Climatic Data Center [2/20/2014];Land-Based Station Data: ASOS 1 Minute Data (6405) 2012 Datasets “64050KABQ201204.dat and 64060KABQ201204.dat” ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/asos-onemin/

- Padro-Martinez LT, Patton AP, Trull JB, Zamore W, Brugge D, Durant JL. Mobile monitoring of particle number concentration and other traffic-related air pollutants in a near-highway neighborhood over the course of a year. Atmos. Environ. 2012;61:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.06.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattinson W, Longley I, Kingham S. Using mobile monitoring to visualise diurnal variation of traffic pollutants across two near-highway neighbourhoods. Atmos. Environ. 2014;94(0):782–792. [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma EJ, Bivand RS. Classes and methods for spatial data in R. R News. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roger S, Bivand EP. Applied spatial data analysis with R. Second edition Springer; NY: 2013. Virgilio Gomez-Rubio. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer CW, Joseph DW, Ollison WM. A Re-Examination of Ambient Air Ozone Monitor Interferences. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2010;60(11):1353–1364. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.60.11.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens JT, Heist DK, Perry SG, Zhang KM. Modeling the effects of a solid barrier on pollutant dispersion under various atmospheric stability conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2013;69:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (AQS) [2/24/2014];Data Mart. EPA AQS Data for the Del Norte High School site (AQS ID 350010023) 2012 http://www.epa.gov/ttn/airs/aqsdatamart/access/interface.htm.

- Wood SN. Thin plate regression splines. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2003;65:95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wood SN. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Statistical Methods) 2011;73:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YF, Hinds WC, Kim S, Shen S, Sioutas C. Study of ultrafine particles near a major highway with heavy-duty diesel traffic. Atmos. Environ. 2002;36(27):4323–4335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YF, Kuhn T, Mayo P, Hinds WC. Comparison of daytime and nighttime concentration profiles and size distributions of ultrafine particles near a major highway. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40(8):2531–2536. doi: 10.1021/es0516514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonum Solutions [2/24/2014];Kml2x. 2013 http://zonums.com/online/kml2x/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.