During the past two decades, researchers have provided evidence to support the notion that the social environment in which people live, as well as their lifestyles and behaviours, can influence the incidence of illness within a population (IOM 1988). They have also demonstrated that a population can achieve long-term health improvements when people become involved in improving the health of their community and work together to effect change (Hanson 1988). The rationale for community-engaged health promotion is aligned with the recognition that lifestyles, behaviours, wellness and illness are all shaped by social, biological and physical environments. This ‘ecological’ view is consistent with health inequalities, unequal distribution of wealth and socioeconomic conditions, leading to an outgrowth of social changes similar to those of earlier decades (Hanson 1988). The strength of community-engaged research is well documented and is recognised as a useful approach for eliminating health disparities and improving health equity. In light of these developments, members of disease prevention groups, such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Awards (CTSA), have expanded efforts to create collaborative environments, strong community action and public policy in ways that support community engagement. To this end, emerging researchers at academic institutions have begun to appreciate the ecological view for eliminating health disparities and promoting social justice.

The purpose of this article is to describe and demonstrate how five projects incorporated key community-engagement principles to conduct research between interdisciplinary research teams from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and African Americans residing in rural South Carolina, also known as Gullahs.

The five projects, which span a 20-year period, will demonstrate how the academic researchers have been able to build relationships and trust with the Gullah population in order to sustain partnerships and to meet major research objectives. Central to this success has been: 1) the establishment of a Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC), which was developed at the inception of the first community-engaged research project; and 2) the integration of clinical and health research with the nine key principles of community-engaged research, as identified by the NIH and discussed below. While successes included the implementation of a working CAC with clear, realistic goals, creation of a DNA data repository and reduction in diabetes-related amputations, there were challenges including structural inequality, organisational and cultural issues and a lack of resources for building sustainable research infrastructure. Major take-home messages and recommendations suggest the need to gain knowledge about the community culture/assets and to embed community cultural context into research approaches.

We begin this article with a brief overview on community engagement and the nine principles, followed by a brief historical background of the Sea Island Gullah population, a description of each project, and an integrated matrix highlighting how the community-engagement principles have been used. The article ends with challenges, lessons learned, and recommendations for community-engaged research.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Loosely defined, community engagement is ‘the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interests or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people’ (CDC 1997, 2011). It is a powerful vehicle to promote environmental and behavioural changes which, in turn, lead to improvements in health and wellbeing of a community. Community-engaged research (CEnR) entails a collaborative partnership between academic researchers and the community. Community engagement with research can be viewed as a continuum, from collaboration on a specific project to a more progressive approach involving greater community involvement, including a shared and equitable partnership that is sustained over time (CDC 2011).

The ‘ideal’ CEnR is a model in which scientific professionals and members of a community work together, as equal partners, in the development, implementation and dissemination of research that is relevant to the community (Israel et al. 1998, 2003). An advantage of this approach is that the processes are bi-directional, allowing researchers to utilise scientific knowledge of an identified health problem facing the community, and for the community to utilise their expertise in the cultural and social contexts of the health issue and potential solutions that may work locally. More importantly, with an engaged partnership approach, research can contribute to decreasing health inequities among disempowered communities and help build capacity by focusing attention on social justice and power sharing (Israel et al. 2003).

An expert task force convened by the NIH reported nine key principles of community engagement, which drew on their knowledge of the literature, as well as their individual and collective experiences (CDC 2011). These principles include:

Be clear about the purposes or goals of the engagement effort and the communities you want to engage.

Become knowledgeable about the community (i.e., culture, economic conditions, social networks, political and power structures, values).

Establish relationships, build trust, work with the formal and informal leadership, and seek commitment to create processes for mobilizing the community.

Accept that collective self-determinism is the responsibility and right of all people in a community.

Partnering with the community is necessary to create change and improve health.

All aspects of community engagement must recognize and respect the diversity of the community.

Community engagement can only be sustained by identifying and mobilizing community assets and strengths and by developing the community’s capacity and resources to make decisions and take action.

Organizations that wish to engage a community must be prepared to release control of actions or interventions to the community and be flexible enough to meet its changing needs.

Community collaborations require long-term commitment by the engaging organization and its partners.

Each project discussed below describes how the above CEnR principles were incorporated into the research approaches within the Gullah communities. The origins of the Gullahs extend back to the late 17th century when their ancestors were captured in Africa and transported to American shores. The Sea Island/Gullah African American (AA) population provides a unique cohort for defining genetic and environmental factors for complex chronic diseases, such as diabetes, autoimmune disorders, particularly lupus, and cancer. This section begins with a brief historical description of the Sea Islands.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE SEA ISLAND CULTURE

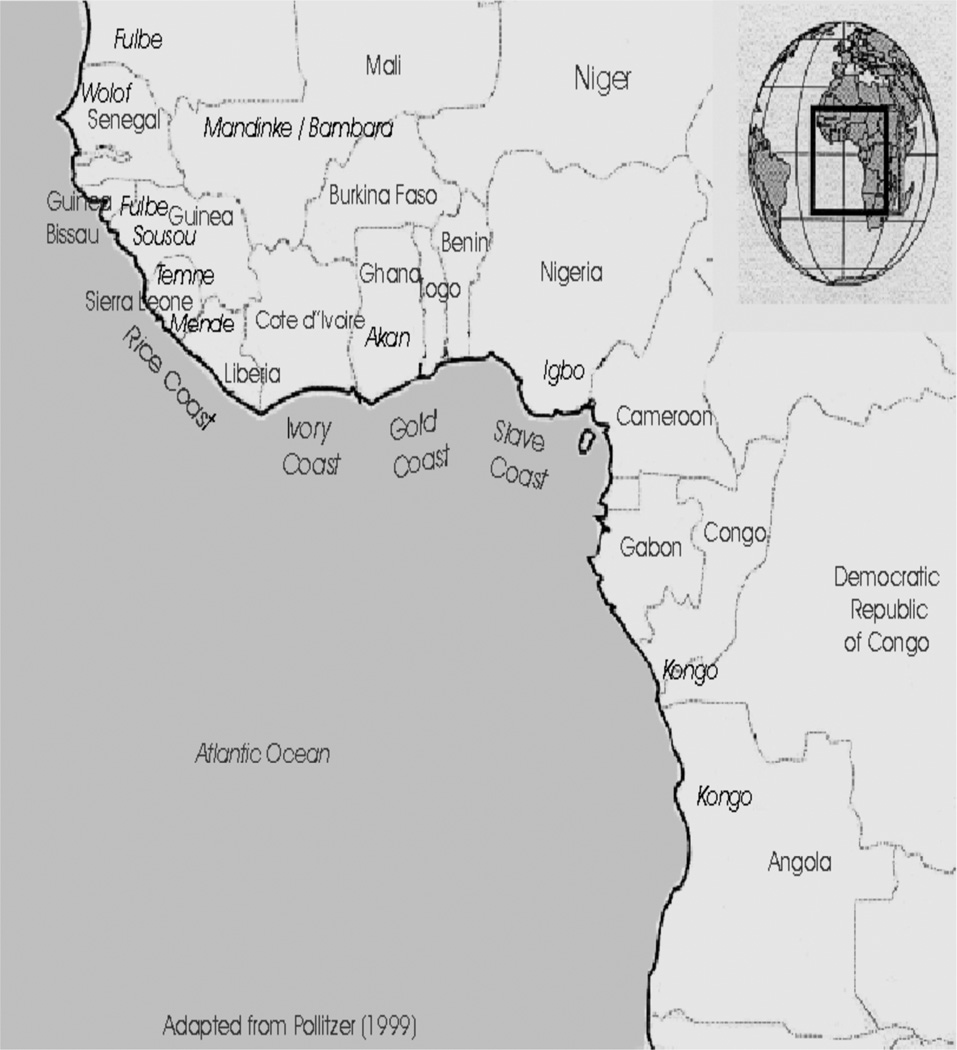

Since the early 1700s, the Sea Island communities have inhabited the barrier islands along the coast of South Carolina (SC) and Georgia (GA) and adjacent coastal communities in Florida. The Sea Islanders, also known as Gullahs, are the descendants of enslaved Africans, and are one of the most distinctive cultural groups that exist in America today. Isolated off the coast for nearly three centuries, the native population developed a vibrant way of life that remains, in many ways, as African as it is American (Jones-Jackson 1987). Historians report that colonists in Carolina sought out Africans from the ‘grain coast’ of West Africa (Opala 1985; Pollitzer 1999) because of their rice-growing expertise: the SC low country was similar to the topography of West Africa and ideally suited for rice cultivation (see Figures 1 and 2). The Gullah language, an English Creole very similar to the modern-day language (Krio) spoken in Sierra Leone, is the preserved spoken language of the Sea Islanders (Opala 1985).

Figure 1.

Map of West Coast of Africa

Figure 2.

Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia (the ‘low country’ region). Map drawing courtesy of Jennifer B. Lessard

GULLAHS IN SOUTH CAROLINA

To highlight the Gullah culture within the proper context, we share a quote from anthropologist William Pollitzer (1999):

The Gullah people are not a museum piece, relics of the past, but rather survivors of enslavement, bondage, discrimination, and white privilege, they are fellow human beings entitled to work out their own destiny.

Several factors, such as geographical, cultural and social isolation, helped preserve the relative homogeneity of the Sea Islanders of South Carolina. It is estimated that 40 per cent of enslaved Africans brought to the United States entered through the port of Charleston from the West Coast of Africa including Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, the Congo and Angola (Jones-Jackson 1987; Pollitzer 1999). The low-lying areas of the SC low country were rife with diseases such as yellow fever, malaria and tuberculosis, and therefore were mostly avoided by European landowners and largely supervised by enslaved African foremen (Pollitzer 1999). This resulted in minimal contact with Europeans and the enslaved Africans from different regions created a fusion of their home cultures and formed a new (Gullah) culture in America. Moreover, this unique culture emerged from eight generations of life under oppressive conditions.

The SC Gullah population is known for preserving more of their African linguistic and cultural heritage than any other African American community studied within the United States. In fact, the SC Gullahs have less racial admixture (3.5 per cent) than any groups tested in the United States (Pollitzer 1999). Their English-based creole language contains many African words and significant influences from African languages in its grammar and sentence structure. Properly referred to as ‘Sea Island Creole’, the Gullah language is related to Jamaican Creole, Barbadian Dialect, Bahamian Dialect and the Krio language of Sierra Leone in West Africa (Hancock 1980; Turner, Mille & Montgomery 1974).

All of the projects described in this article used a community-engaged approach and are rooted in the unique history of coastal South Carolina Gullah communities.

OVERVIEW OF COMMUNITY-ENGAGED RESEARCH APPROACH

True community engagement can be difficult and labour intensive, requiring dedicated resources to help ensure its success. The best known framework and approach for CEnR is Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), defined by Israel et al. (1988) as an interdisciplinary research methodology in which scientific professionals and members of a specific community work together as equal partners in the development, implementation and dissemination of research that is relevant to the community. Community engagement benefits from using the participatory research principle of shared power. More importantly, because CBPR is bi-directional and can contribute to decreasing health inequities among disempowered communities, CBPR can help build capacity in under-served populations, by focusing attention on social justice and sharing power. Unlike CEnR, CBPR researchers present or bring to the community their scientific knowledge or a problem that has been identified from clinical data. For example, the researchers from both Project SuGar and SLEIGH used their scientific knowledge to identify a clinical problem with disparities in prevalence of diabetes and lupus among the Sea Island population. The heart of our CEnR occurred within the SC Gullah communities. Our hope is that by further investigating these diseases within this unique population, the results will be translated into methods of prevention, earlier diagnosis, social justice and more effective treatments to benefit their communities.

Specific examples of how each project engaged the community are presented below and summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of community-engaged research with Sea Island Community

| Research studies |

Research goal/ purpose |

Community partners |

Community services provided |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project SuGar | Isolate and identify genes responsible for T2DM and obesity | Citizen Advisory Board (CAC), later known as Sea Islands Family Project (SIFP) Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) |

Project SuGar Mobile Health Unit Free health screenings and diabetes education |

Recruited 650 African American (AA) families Created DNA and data repository DNA registries used to identify markers for T2DM |

| COHR | Determine magnitude of oral health disease Isolate genes that increase susceptibility to periodontal disease Determine oral health treatment strategies that work |

FQHC dental clinics SIFP Churches Mayor’s office |

Dental care Free oral examinations Dental education |

Higher rates of periodontal disease among Gullahs compared to other AAs Deep cleaning, with no antibiotic, enough to improve periodontal health and glycemic control in T2DM Gullah AAs New oral health promoter intervention being tested in churches |

| SLEIGH | Identify genes and environmental triggers that cause lupus and lupus-related autoimmunity, and assess the prevalence and severity of lupus in the Gullah population | Local lupus support and patient advocacy groups SIFP |

Free autoimmune disease screenings and lupus education | Higher prevalence of lupus among Gullah families compared to other population studies Finding of potential genes predisposing to lupus and potential environmental triggers of disease |

| Hollings Cancer Center | Impact of community education to improve cancer knowledge and receptivity to cancer trials To test the impact of genetic polymorphisms on racial disparities in breast and prostate cancer incidence and mortality |

15 civic and service organisations SIFP |

Train the Trainer modules in community Mobile health van |

Cancer knowledge can improve with community education More positive perceptions of cancer clinical trials following the intervention 40 of the trained lay facilitators have conducted 104 sessions, reaching 3292 community members Recently funded genetic studies are in the early stages of data collection |

| REACH | Decrease or eliminate disparities for African Americans with T2DM | Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition | Educational pamphlets, ‘My Guide to Sugar Diabetes’ Community education, free self-management diabetes education, and linkages related to managing diabetes and seeking appropriate resources Worked with local coalitions to establish 501(c)(3) non-profit organisations, and provide training for grant writing and methods for obtaining funds for sustainability beyond REACH CDC funding |

Engaged community in elimination or reduction in disparities related to A1C, kidney and lipid testing in AAs with T2DM who visit their provider Almost 50% reduction in diabetes-related amputation rates across the two county areas Established ongoing diabetes self-management education programs in several sites |

Project SuGar (1995–2003)

Initiated in 1995, Project SuGar (Sea Island Genetic African American Families Registry) was the first of many genetic studies to be conducted among the SC Sea Islanders. The Sea Islands population has a particularly high degree of genetic risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), with a sibling relative risk of 3.3 for T2DM, a figure exceeding that in many other communities (Garvey, McLean & Spruill 2003). The incidence of diabetes among the Sea Islanders has been projected at 20 per cent (Jenkins et al. 2004; McLean et al. 2003), which is much higher than in the general African American population. The scientific aim of Project SuGar was to isolate and identify genes responsible for the expression of T2DM and obesity in Gullah speaking AAs. The intent and goal of the project was to create a DNA repository linked to clinical data on 400 AA families affected with T2DM.

Adhering to the principles of CEnR, the research team sought to engage the community through the formation of a Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC) at the inception of the project. Community stakeholders were identified and a 15-member CAC was formed of representatives from a cross-section of the Gullah community, including the faith community, state legislature, community health centres, educational establishments, research participants, consumers, cultural organisations, formal and informal leaders, and members with and without a scientific background.

In partnership with the CAC, a recruitment model/strategy known as the Community Plan Reward (CPR) was adopted. The three components of the model include community involvement, flexible protocols, and rewarding the community with tangible benefits. The CPR model proposes that, when services are provided to the community (e.g. health fairs, mobile health vans, community education), in tandem with local community advisory committees, the possibilities of recruiting participants into research and clinical trials are significantly enhanced. This model has demonstrated benefits to both the participants and the researchers (Spruill 2004). In addition, decision-making regarding recruitment was shared, resulting in a flexible study protocol, which included weekend recruitment efforts and home visits. The Project SuGar research team sought to hire nurses who reflected the study population, had respect for their culture, and could speak and understand the ‘Gullah language’. A major request from the CAC from the outset was that the academic researchers attempt to balance research with community service projects. This request has been upheld by Project SuGar, as well as by research projects discussed later.

From 1995 through 2003, Project SuGAR recruited Gullah families living on the SC Sea Islands. Project SuGar now has a data and DNA repository of 1324 individuals, or 650 families, which includes 1105 individuals with T2DM. This is one of the largest assembled cohorts of AAs with T2DM in the south-east Gullah families. Genome-wide linkage scans revealed a novel T2DM locus in this population on chromosome 14q (C14) and 7q (C7) that appears to reduce age of diabetes onset (Sale et al. 2009).

In 2003, genetic-related studies among the Gullah population were united under one umbrella and the CAC changed its name to the Sea Islands Families Project (SIFP). The purpose of the SIFP is to formalise new partnerships between the academic institution and the community, share resources and ideas, avoid duplication of community efforts, and provide guidance and recommendations to the new research teams interested in doing research among the Sea Islanders (see below).

Center for Oral Health Research (2001–present)

Periodontal disease affects one or more of the tooth-supporting tissues. There is evidence that periodontal disease can worsen diabetic control and (vice versa) and that proper management of the disease can improve diabetic control (Soskolne & Klinger 2001). Several genetic polymorphisms have been associated with chronic, severe periodontitis. The unique homogeneity of Sea Islanders makes this population especially attractive for studying the influence of genetics on the expression of periodontal disease.

Building upon the positive community partnership developed by Project SuGar, the first Center for Oral Health Research (COHR) project funded through the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) for Oral Health mechanism became the second successful community-engaged genetic project under the SIFP umbrella.

There are now multiple projects under the COHR umbrella. The first project was a genetic/epidemiologic cross-sectional study that investigated the prevalence of caries and periodontal disease in the T2DM Gullah population (Fernandes et al. 2009; Marlow et al. 2011a). The second project was a double-blind clinical trial to investigate the need for antibiotic therapy in conjunction with mechanical non-surgical therapy in the treatment of periodontal disease in this same population (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2010; Marlow et al. 2011b). Membership in the SIFP enhanced rapport, communication, cultural sensitivity and cultural humility. Patients were valued and compensated with gift cards as an appreciation for their time and, similarly to the Project SuGar design, the results of their blood work were mailed to them along with a thank you letter.

The latest projects have developed upon the communities’ interest in improving their oral health and have involved community members as co-investigators. They have been funded recently by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and the United States Department of Defense. Both projects have been developed using a CEnR approach and their main goals are to develop culturally sensitive oral-health multi-level (church, group, individual) interventions and to disseminate the latest technology to community clinics, thus improving the services available in community clinics and decreasing oral health disparities in the Gullah population. Local community members have been hired and trained to act as Community Oral Health Promoters, and a study-specific Community Advisory Board has been formed, mainly composed of church leaders and town administrators, with the objectives of enhancing communication between the research group and the community, improving results/products dissemination, and assuring cultural sensitivity in all aspects of the research projects. Individual and small church advisory boards have also been formed in each of the participating churches to facilitate the design and implementation of church-level interventions.

SLEIGH (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Gullah Health) (2003–present)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus) is an autoimmune disease that affects approximately 1 in 250 AA women of childbearing potential. AAs have a threefold increased prevalence of lupus, develop lupus at an earlier age, and have increased lupus-related morbidity and mortality compared to Caucasians (Bernatsky et al. 2006; Fernandez et al. 2005). Multiple factors, including genetic, environmental and socioeconomic, likely underlie the ethnic disparity in lupus (Rahman & Isenberg 2008). Socioeconomic and genetic differences alone, however, cannot explain the significant increase in prevalence of lupus in the past 20 years or the gradient of lupus between West Africa, where it is a rare disease, and the United States, where it is prevalent (Gilkeson et al. 2011). These latter findings suggest environmental factors play a key role in triggering the onset of lupus and impacting disease severity. Genetic and environmental heterogeneity within the United States African American population has confounded previous efforts to identify causative factors in lupus and/or its co-morbidities. The lower non-African genetic admixture among Gullah AAs makes them a unique population in which to study complex multifactorial diseases.

The SLEIGH study was established in 2003 to find the genes and environmental triggers that cause lupus and lupus-related autoimmunity, and to assess the prevalence and severity of lupus in the Gullah AA population. There are several active research studies, under the umbrella of the longitudinal SLEIGH cohort, recruiting from the Sea Island communities. In 2002, a relationship was formed between the lupus investigators and the SIFP developing the protocol for the SLEIGH study. The lupus investigators presented at an SIFP meeting what was known about the prevalence of lupus among AAs in coastal SC, including hospitalisation data showing increased mortality among AA women with lupus, and continued to meet with SIFP members to help develop a protocol to address the question of lupus among the Gullah. In addition to discussing project progress and results at every quarterly SIFP meeting since that time, in 2010 the project organised a Steering Committee, which includes SIFP members particularly interested in lupus and other academic partners, in order to discuss the relevant studies more frequently and in more detail. The Steering Committee has also helped direct the community outreach and education programs and participated in evaluation of the SLEIGH study progress in reaching the research and educational objectives.

Following the recruitment service-orientated model (CPR) from Project SuGar, the researchers have been successful in partnering with local lupus support groups and patient advocacy organisations, including the Lupus Foundation of America, and community members have initiated studies to address areas related to lupus of particular interest to them utilising the SLEIGH cohort. Although this requires the community members to become trained in human research methods and be approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as study personnel, it has invariably been a worthwhile and rewarding experience. In respect to skill building with community stakeholders, a community liaison who reflected the study population was hired to provide consistent representation at the CAC/SIFP quarterly meetings and the weekly team meetings.

Utilising principles from CEnR, and building on positive relationships with the community established by the previous research projects, the SLEIGH team was able to recruit a large number of Gullah families to meet the goal of the project. The SLEIGH study has grown to include 237 patients with lupus, 166 unrelated controls and 220 family-member controls to date. Findings from SLEIGH to date suggest a higher than predicted prevalence of multiplex families, with 26.6 per cent of patients coming from multi-affected families, and a significantly lower age at lupus diagnosis in the offspring of a parent with lupus, which could be attributed to genetic ‘anticipation’ (Kamen et al. 2008). There is also a high prevalence of autoantibody seropositivity in first-degree relatives of patients, with a notable 35 per cent of all SLEIGH first-degree relatives testing positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) at a significant titre of ≥ 1:120. One of the investigations into potential environmental triggers of autoimmunity led to the discovery of an alarming 95 per cent prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Gullah AAs, which subsequently led to further studies into the impact of vitamin D deficiency on immune and bone health (Ben-Zvi et al. 2010; Kamen et al. 2008). A clinical trial providing oral vitamin D to patients with SLE found that higher than expected doses of vitamin D are required to achieve normal levels, and that fortunately these doses are safe and well tolerated.

In 2009, with funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) at the National Institutes of Health, the researchers have been able to continue the investigation of environmental triggers of autoimmunity among the Sea Island Gullah population. This four-year study is examining exposure to and blood levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) found in local dietary staples such as fish.

Hollings Cancer Center/Cancer Prevention & Control (2011–present)

Since 2000, through the Cancer Screening and Patient Navigation Services in the Sea Island community, the Hollings Cancer Center (HCC) has conducted cancer-screening activities via the HCC’s Mobile Health Unit at a local federally qualified community health centre on Johns Islands, screening well over 3500 participants. The purpose of this project is to share awareness of and strategies for preventable cancers among African Americans.

The HCC approach to CEnR started with the identification of a clinical problem (high prevalence of breast and prostate cancer among the Sea Islanders) by academic researchers and forging of a partnership with community ‘champion’ members and organisations. Each lay facilitator who was trained during the program signed a contract/agreement to conduct two cancer education training sessions in his/her community within 12 months. The research team at HCC adhered to principals of CEnR and shared the credit for success with the community partners.

The signature programs, Cancer Education Training Program in the Sea Island Community and Community Engagement Activities Conducted in Cancer Education Training Program, have reached a total of 469 individuals. The Cancer Education Training Program (2009) was conducted in a targeted Sea Islands community (Johns Island). The program consisted of a four-hour evidence-based cancer education program in which there was a three-hour component focusing on general cancer knowledge, a 30-minute component specifically on prostate cancer knowledge, and another 30-minute component on cancer clinical trials knowledge. Participants engaged in role plays as they practised sharing the information they had learned with others. Results related to cancer knowledge outcomes are reported elsewhere and demonstrate that general cancer and prostate cancer knowledge scores increased significantly following the cancer education program (Ford et al. 2011).

The Community Engagement Activities Conducted in Cancer Education Training Program used community skill building to employ the Train the Trainer design. This was a four-hour session conducted at each site and focused on training community members to teach others in their communities about cancer prevention and control, lifestyle interventions, cancer screening, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment options. The community partnership included a self-identified champion, or community leader, responsible for recruiting participants. Each community person received a binder containing copies of all of the materials presented during the four-hour training session, including evidence-based information related to cancer screening, early detection, treatment and participation in cancer clinical trials. Adhering to the principles of shared power, the community champion decided which training product (transparencies, memory sticks and/or CDs) worked best. Nine trained facilitators conducted 16 cancer education training programs, reaching 469 individuals. Results indicate more positive perceptions of cancer clinical trials following the intervention (p<0.001).

REACH (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) (1999–present)

Since 1999, REACH has focused on improving type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management and reducing disparities related to health care and complications through CEnR and building partnerships. The REACH Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition represents a diverse group of academic and lay community members. The Coalition is governed by by-laws and community-based participatory actions. REACH focuses on improving community-wide outcomes through: 1) community education on T2DM prevention and control; 2) health system improvements through continuous quality improvements; and 3) Coalition building, policy change and sustainability.

Forging partnerships with existing partners resulted in collaboration with many Sea Island community partners. The REACH academic partners bring the science of diabetes to the communities, while community members decide when, where and how to apply or integrate evidence-based practices into community and health systems, while also generating ‘community-based evidence’ for change. The partners then work together to address and eliminate disparities in health and health care.

The Coalition has developed community education programs, which are delivered by Community Health Workers (CHWs), as well as the multiple partners. In multiple community sites, especially in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), culturally relevant T2DM self-management training is delivered weekly by Certified Diabetes Educators in collaboration with CHWs. Additionally, for resource sharing, REACH offers a ‘Strip-It’ program that provides reduced-cost glucose monitoring strips for the uninsured and underinsured through local diabetes coalitions in each county and partner fundraising, as well as an educational guide, ‘My guide to sugar diabetes’, and foot care education (http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/reach/materials/index.html).

The REACH evaluation team reports a 44 per cent reduction in DM-related amputations in AAs (Jenkins et al. 2011) and a reduction of almost 50 per cent in AA men with diabetes. Although improved care has not translated into significantly improved A1C control – the hallmark of decreasing T2DM complications – the Coalitions (REACH Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition and the local Coalitions in each county) have demonstrated a positive trend in blood pressure control and a small, though at this time insignificant, trend in A1C control. And for community residents who attend three or more REACH diabetes self-management education classes, a significant decrease in A1C control has been observed (from an average of 10.3 per cent A1C to 7.1 per cent) (Jenkins et al. 2011). However, DM control (A1C, blood pressure, lipids, and associated complications of stroke, cardiovascular and kidney disease) for community residents remains a challenge and the focus of current actions through REACH.

APPLYING COMMUNITY-ENGAGED RESEARCH PRINCIPLES

Our partnerships between communities and academic institutions as a strategy for social change are gaining recognition and momentum. In their truest form, these partnerships require time and commitment but have the power to transform the individuals, the communities and the institutions that are part of them. Our projects reflect different points on the continuum of CEnR, from collaboration on certain aspects of the research (i.e. recruitment, implementation) to an equitable partnership with community members as co-investigators who work side by side with academic researchers in all phases of the research partnership. Three projects (SuGar, COHR, and SLEIGH) focused on the genetic influence on diseases among the SC Gullah population and worked with the SIFP to address cultural preferences, recruitment and implementation strategies. The HCC projects adopted similar CEnR approaches. REACH has progressed along this continuum to involve shared decision-making with the Coalitions and shared protocol development, implementation, evaluation and dissemination strategies. The latest COHR projects reflect the ideal point on the CEnR continuum, with community co-investigators and partnership in all phases of the research. Table 2 highlights each study and adoption of the established CEnR principles.

Table 2.

Case studies and principles for community engagement

| Before starting CEnR | What is necessary? | Consideration for success | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case example | Principle 1 | Principle 2 | Principle 3 | Principle 4 | Principle 5 | Principle 6 | Principle 7 | Principle 8 | Principle 9 |

| Establish clear goals | Become knowledgeable about the community |

Establish relationships | Develop community self-determination |

Partner with the community |

Maintain respect for community diversity |

Mobilise community assets |

Release control | Maintain community collaboration |

|

| Project SuGar | Improve T2DM prevention and treatment with new genetic discoveries |

CAC members had extensive knowledge of Gullah culture Identified community strengths |

CAC organised at inception of project CAC composed of formal and informal leaders |

Community embraced cultural heritage by celebrating annual Gullah festival, Penn Center Heritage Day and Moja Arts Festival, and invited research team |

Memoranda of agreement with five FQHCs within the recruitment area |

Multiple recruitment strategies All staff/ volunteers orientated to Gullah culture Hire staff from community |

CAC request tangible benefits, i.e. education and health screenings and flexible protocol |

CAC co-chaired by community stakeholder |

Although the CAC was formalised in 1995, it continues to meet today Community-wide dissemination events |

| COHR | Develop a model to improve oral health of rural Gullah communities |

Sought input from pre- established SIFP Created study-specific community advisory board Research team participated in multiple community events Community members hired as part of the research team Meetings with local leaders and historians to learn more about the culture and habits |

SIFP Partnerships were slowly formed with different community/church leaders Partnership established with community clinics |

Participated in multiple cultural events, educating the community on how to take better care of their oral health needs Research team became involved in other projects, led by the community |

Memoranda of understanding signed with three different community dental clinics Formal partnership established with multiple churches in the Sea Island communities |

Smaller community advisory boards formed in each participating community/church Hired community members to be part of the research team Used different recruitment/ intervention strategies, based on community input |

Used community’s strengths (i.e. people assets and current infrastructure (church, community, dental clinics) to improve different aspects of the projects |

Community and academic partners are Co-Principal Investigators in different projects Community organisation is funded by grant support |

Community is involved in every aspect of the project, from the problem identification, through finding possible solutions to results dissemination Research team involved in community-led projects |

| SLEIGH | Decrease lupus morbidity and mortality among Gullah through new genetic discoveries, to improve prevention and treatment modalities |

Sought input from pre- established SIFP to better inform protocol design and define recruitment strategies |

Organised a smaller steering committee for the project |

Provided educational seminars on lupus for the community Performed autoimmune disease screenings within the community Invited community members for autoimmune disease testing and counselling |

Partnered with patient advocacy and support groups Hired a community liaison, who is also an SIFP member |

Smaller steering committee formed in addition to quarterly meeting with the SIFP |

Multiple approaches and strategies based on community input and requests |

Community members have initiated studies to address research questions utilising the SLEIGH cohort and have become approved study personnel |

Continue to provide community services and feedback to the community on study findings and implications Maintaining up-to-date contact information for study participants is a priority |

| REACH | Decrease disparities for AA Gullah with diabetes |

Employed members of the community to work collaboratively with researchers to identify goals and objectives, and design activities and evaluation methods for identifying and reducing disparities |

Organised a coalition of community members and academic researchers to work together to identify and establish relationships with community leaders and members of the community |

Researchers and public health leaders shared the science of diabetes with the community, while the community leaders and members decided when, where and how to apply the ‘science of diabetes’ within their communities |

Memoranda of agreement with FQHCs, community organisations and libraries within the community |

Multiple approaches and strategies based on community input and requests |

The community organisations and agencies were invited to identify a member of their community to lead community activities and serve as resources Community organisations were invited to become Coalition partners and receive funding for implementing activities |

Identified members of the Coalition and employees from the community were involved in decision- making related to ongoing activities of REACH |

Community members determined when, where, what and how to engage community in activities, while REACH employees and Coalition members assisted with implementing and evaluating community progress in addressing disparities related to diabetes management and control |

| Hollings Cancer Center | Improve cancer disparities Identify effective cancer awareness, prevention and treatment in Sea Islands communities |

Research team members participated in training sessions on Sea Island/ Gullah culture Research team members talked with local historians and read literature |

Research team attended cultural events in the community Conducted cancer education training programs with Gullah community members |

Advisory committee comprised of Sea Island community members |

Provided cancer screening, patient navigation and cancer education services in the Sea Island communities ‘Train the Trainer’ approach with lay community facilitators |

HCC recently conducted a cultural competence training led by the internationally renowned National Coalition Building Institute group |

Participated in Sea Island Community Celebration; as a result, one of the community leaders will play a major role in organising the research team to conduct a cancer education/ training program with members of her community |

Presented initial research to SIFP to obtain approval and input before moving forward with the studies |

Continue to provide tangible services to community members and will expect community members to highlight areas of cancer research in which they would like to collaborate with members of the research team |

CHALLENGES, LESSONS LEARNED, RECOMMENDATIONS

Challenges experienced by our research teams have been organised into three major areas: 1) structural inequality; 2) organisational and cultural issues; and 3) resources for sustainable infrastructure.

Structural Inequality

Structural inequalities observed by our team include common issues experienced by rural isolated communities, such as distance from health service centres, lack of adequate transportation systems, lack of access to healthy foods (from grocery stores) and poor communication systems. Rural communities, such as the Sea Island Gullah communities, have difficulty accessing these services due to their geographical location.

Recommendation

One strategy, as recommended early in this process by the original Citizen Advisory Committee, was to balance the research agendas with community services and to provide tangible health benefits to the community. For example, Project SuGar provided free diabetes education/screening; HCC provides prostate and breast pap screening, utilising the mobile health unit; COHR provides dental examination and primary therapy at no cost; REACH provides health fairs and community education.

Organisational and Cultural Issues

Historically, African Americans as a group have not participated in clinical trials and health-related research, especially genetic research, and the numbers are more dismal among rural AA (Bonvicini 1998; Byrd et al. 2009). A history of exploitation in minority rural communities may manifest in a number of ways, including fear and lack of trust and participation in research. Lack of trust has been one of the major challenges faced by researchers trying to conduct CEnR among the Sea Islanders. Isolated from the mainland until the 1950s, the Sea Island communities have been largely ignored, victims of benign neglect, and have experienced racial discrimination and Jim Crow laws. They are suspicious of ‘outsiders’, and their ingrained cultural norms have been passed down through many generations. With a history of no direct benefit from research, in some cases experiencing harm from research, and no feedback or results of studies, it is not unusual to encounter participants with cultural memories of negative experiences, anger and reluctance to get involved – even when the research is proposing a CEnR approach. These behaviours are validated by the literature, in that the most frequently mentioned challenge to conducting effective community-based research is lack of trust and perceived lack of respect, particularly between researchers and community members (Israel 1988, 2003).

Recommendation

As the first genetic research among the Sea Islanders, Project SuGar spent the first year building relationships, identifying and seeking support from both formal and informal leaders, and hiring credible and influential Gullah leaders as part of the project staff. Explicit in the comments from the stakeholders was the need to ‘sit at the table’ and to formally organise a CAC. It was important for the academic partners to both listen to and acknowledge the past negative and exploitative history of this community. This often emotionally difficult and time-consuming process, however, enabled the other projects to build upon the prior positive working relationships of Project SuGar as a viable strategy for conducting CEnR.

Equally important for the academic organisational culture is broad-based support from the institution and principal investigators and provision of resources for the community beyond the scope of the research agenda. All teams have written these provisions into grant funding and/or have been able to identify other academic resources to enable participation in local health fairs and Gullah cultural events.

Resources for Sustainable Infrastructure

The most challenging and important lesson learned is the continued need for resources, such as research infrastructure and community liaison, to maintain ongoing communication channels between the community partners and the academic institution, especially between funding grants. Currently, a formal infrastructure with ongoing financial support for the SIFP does not exist; instead, resources and administrative tasks for quarterly meetings, along with the commitment of SIFP members to attend quarterly meetings, are shared among the research projects. Ongoing community collaboration is critical for establishing and maintaining trust and respect between the academic and community partners. Paramount to this is the need to identify funds and resources to formalise the infrastructure and to continue maintaining and improving community ties. Yet, despite these challenges, all of our CEnR projects have enjoyed some degree of success, by utilising community-engagement principles and drawing on the insight, planning and relationships built during the initial study, Project SuGar, as well as the commitment of both academic and research partners.

Lessons learned

Through clearly articulating and sharing goals, becoming knowledgeable about the community culture and embedding the cultural context with research approaches, important lessons have been learned. Utilising existing community assets (especially people) and community infrastructure (community clinics and churches) has also benefited these projects. In addition to the above, it is important that community academic partners have patience and allow time to build relationships, to recognise, respect and include the local expertise, to use a variety of recruitment strategies, and to acknowledge memories that may lead to distrust of researchers.

We are also aware that dissemination of research findings to the community can be challenging for multiple projects. To address this problem, a Community Celebration was held on 21 January 2012 at a local high school, to share findings from all the projects under the SIFP umbrella. The SIFP was active in planning this event, which combined a mutual sharing of research findings and cultural activities (e.g. local singers and dancers). The event alternated research and community presentations and was led by a local Gullah Councilwoman. Researchers from all projects shared results of their study findings along with moving testimonials from research participants. Over 200 community participants attended this historical event.

CONCLUSION

The ultimate goal of clinical and health services research is to create knowledge that can be used to improve health and health care for individuals and communities. To achieve this goal effectively, especially when working with under-served populations, investigators are increasingly incorporating community input into all stages of the research. Community-based participatory research, which provides principles and processes for obtaining community input and engagement, is being increasingly used in traditional medical research settings. True community engagement can be difficult and labour intensive and require dedicated resources to help ensure its success. Our work and our journey to date is a small testament to the potential for systems change and social action on health inequalities. It is by no means without flaws and is still evolving. Nonetheless, we are a tight-knit group of like-minded researchers, research staff and community members who are committed to the principles of CEnR, in that we strive to provide ongoing capacity building and improved quality of life for our Sea Island families. The SIFP continues to meet quarterly at the academic institution, and community members have expressed interest in becoming a 501(c)(3) non-profit organisation with hopes of attracting funding to promote sustainability. To this end, we offer the following recommendations for academic and community sustainability:

-

—

Federal funding agencies need to re-examine funding priorities, as well as how funding is structured, reviewed, distributed and evaluated, to support higher educational community partnerships.

-

—

Academic partners must work together with community partners to change the culture of higher education to include those values that support communities as equal partners.

-

—

To enhance understanding and respect, academic partners must acknowledge the strength, value and culture of the community.

-

—

Community partners have the responsibility to share their collective wisdom and knowledge with academic partners and funding agencies.

-

—

Academic institutions should support community members as civic leaders, change agents and community-based researchers.

-

—

Academic institutions should compensate community members for their expertise.

-

—

Both community and academic partners should develop principles of participation and written agreements to clarify terms of engagement and expectations.

REFERENCES

- Bandyopadhyay D, Marlow N, Fernandes J, Leite R. Periodontal disease progression and glycaemic control among Gullah African Americans with type-2 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2010;37:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-zvi I, Aranow C, Mackay M, Stanevsky A, Kamen D, Marinescu l, Collins C, Gilkeson G, Diamond B, Hardin J. The impact of vitamin D on dendritic cell function in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2010;5:9193e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernatsky S, Boivin J, Joseph l, Manzi S, Ginzler E, Gladman D, Urowitz M, Fortin P, Petri M, Barr S, Gordon C, Bae S, Isenberg D, Zoma A, Aranow C, Dooley M, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Steinsson K, Alarcon G, Senecal J, Zummer M, Hanly J, Ensworth S, Pope J, Edworthy S, Rahman A, Sibley J, El-Gabalawy H, McCarthy T, St Pierre Y, Clarke A, Ramsey-Goldman R. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54:2550–2557. doi: 10.1002/art.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvicini K. The art of recruitment: The foundation of family and linkage studies of psychiatric illness. Family Process. 1998;37:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1998.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd G, Vance M, Edwards C, Taylor V. Ascertaining older African Americans for genetic studies in Alzheimer disease. Alzeimer and Dementia. 2009;5:234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Principles of community engagement. Atlanta, GA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Principles of community engagement. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J, Wiegand R, Salinas C, Grossi S, Sanders J, Lopes-Virella M, Slate E. Periodontal disease status in Gullah African Americans with type 2 diabetes living in South Carolina. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2009;80:1062–1068. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M, Calvo-Alen J, Alarcon G, Roseman J, Bastian H, Fessler B, McGwin G, Jr, Vila L, Sanchez M, Reveille J. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA: xxi): Disease activity, damage accrual, and vascular events in pre- and postmenopausal women. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52:1655–1664. doi: 10.1002/art.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M, Wahlquist A, Ridgeway C, Streets J, Mitchum K, Harper R, Jr, Hamilton I, Etheredge J, Jefferson M, Varner H, Campbell K, Garrett-Mayer E. Evaluating an intervention to increase cancer knowledge in racially diverse communities in South Carolina. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;83:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey W, Mclean D, Jr, Spruill I. The search for obesity genes in isolated populations: Gullah speaking African Americans and the role of uncoupling protein 3 as a thrifty gene. In: Medeiros G, Halpern A, Bouchard C, editors. Progress in obesity research. Paris: Hohn Libbey Eurotext; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilkeson G, James J, Kamen D, Knackstedt T, Maggi D, Meyer A, Ruth N. The United States to Africa lupus prevalence gradient revisited. Lupus Now. 2011;20:1095–1103. doi: 10.1177/0961203311404915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock I. Gullah and Barbadian – origins and relationships. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1980;55:17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P. Citizen involvement in community health promotion: A role application of CDC’s patch model. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 1988;9:177–186. doi: 10.2190/FMWL-59TW-T3CL-VJ16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) The future of public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen A, Guzman J. Review of community-based research assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1988;192:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen A, Guzman J. Community-based participatory research for health. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory principles. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, McNary S, Carlson B, King M, Hossler C, Magwood G, Zheng D, Hendrix K, Beck L, Linnen F, Thomas V, Powell S, Ma’at I. Reducing disparities for African Americans with diabetes: Progress made by the REACH 2010 Charleston and Georgetown diabetes coalition. Public Health Reports. 2004;119:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Myers P, Heidari K, Kelechi T, Buckner-Brown J. Efforts to decrease diabetes-related amputations in African Americans by the racial and ethnic approaches to community health by Charleston and Georgetown diabetes coalition. Family & Community Health. 2011;34(suppl. 1):63–78s. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318202bc0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Jackson P. When roots die. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kamen D, Barron M, Parker T, Shaftman S, Bruner G, Aberle T, James J, Scofield R, Harley J, Gilkeson G. Autoantibody prevalence and lupus characteristics in a unique African American population. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58:1237–1247. doi: 10.1002/art.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow N, Slate E, Bandyopadhyay D, Fernandes J, Leite R. Health insurance status is associated with periodontal disease progression among Gullah African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2011a;71:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow N, Slate E, Bandyopadhyay D, Fernandes J, Salinas C. An evaluation of serum albumin, root caries, and other covariates in Gullah African Americans with type-2 diabetes. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2011b;39:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean D, Jr, Spruill I, Gevao S, Morrison E, Bernard O, Argyropoulos G, Garvey W. Three novel mtDNA restriction site polymorphisms allow exploration of population affinities of African Americans. American Journal of Human Biology. 2003;75:147–161. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opala J. The Gullahs: Rice, slavery, and the Sierra Leone–American connection. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1985. [7 May, 2012]. viewed, www.yale.edu/glc/gullah/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitzer W. The Gullah people and their African heritage. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Isenberg D. Systemic lupus erythematosus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:929–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale M, Lu L, Spruill I, Fernandes J, Lok K, Divers J, Langefeld C, Garvey W. Genome-wide linkage scan in Gullah-speaking African American families with type 2 diabetes: The Sea Islands Genetic African American Registry (Project SuGar) Diabetes. 2009;58:260–267. doi: 10.2337/db08-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soskolne W, Klinger A. The relationship between periodontal diseases and diabetes: An overview. Annals of Periodontology. 2001;6:91–98. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruill I. Project SuGar: A recruitment model for successful African–American participation in health research. Journal of National Black Nurses Association. 2004;15:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L, Mille K, Montgomery M. Africanisms in the Gullah dialect. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]