Abstract

Electroreception is an ancient subdivision of the lateral line sensory system, found in all major vertebrate groups (though lost in frogs, amniotes, and most ray-finned fishes). Electroreception is mediated by “hair cells” in ampullary organs, distributed in fields flanking lines of mechanosensory hair cell-containing neuromasts that detect local water movement. Neuromasts, and afferent neurons for both neuromasts and ampullary organs, develop from lateral line placodes. Although ampullary organs in the axolotl (a representative of the lobe-finned clade of bony fishes) are lateral line placode-derived, non-placodal origins have been proposed for electroreceptors in other taxa. Here we show morphological and molecular data describing lateral line system development in the basal ray-finned fish Polyodon spathula, and present fate-mapping data that conclusively demonstrate a lateral line placode origin for ampullary organs and neuromasts. Together with the axolotl data, this confirms that ampullary organs are ancestrally lateral line placode-derived in bony fishes.

Keywords: paddlefish, lateral line, electroreceptors, neuromasts, ampullary organs, placodes, hair cells

Introduction

The mechanosensory and electrosensory divisions of the lateral line system enable fishes and amphibians to detect changes in local water flow and weak electric fields, respectively1,2. Lateral line mechanosensory hair cells, which are essentially identical to inner ear vestibular hair cells, are collected in neuromasts, small sense organs arranged in characteristic lines over the head and trunk (both superficially and in canals linked to the surface by pores). Neuromasts act as displacement detectors of local water flow, used for prey/predator detection, obstacle avoidance, and behaviours such as schooling. Electrosensory hair cells are collected in ampullary organs3,4, either at the surface or recessed in pores filled with mucous jelly of low electrical resistance, distributed in fields flanking the lines of mechanosensory neuromasts5,6. Transduction is direct: cathodal stimuli open voltage-gated calcium channels in the apical membrane3; the information is used for prey/predator detection, orientation and migration. Afferent innervation for mechanosensory hair cells in a given neuromast line, and for electrosensory hair cells in the ampullary organ fields flanking that line, is provided by neurons within a specific lateral line ganglion7. The mechanisms underlying the development of the mechanosensory lateral line system are increasingly well understood6,8-12. However, the development of electrosensory hair cells, and the extent to which it is similar to the development of mechanosensory hair cells, remain little explored.

The evolutionary history of the lateral line system shows multiple independent losses of the electrosensory subdivision5,13-15, suggesting that its development must be independent of the mechanosensory subdivision, at least to some extent. Both mechanosensory and electrosensory systems are found in all major vertebrate groups, including jawless fishes (lampreys, though not hagfishes), cartilaginous fishes (chondrichthyans), and bony fishes (osteichthyans) (Fig. 1a). Within the lobe-finned bony fishes (sarcopterygians), frogs lack electroreceptors, while amniotes seem to have lost the entire lateral line system with the transition to terrestrial life5,13-15. Within the ray-finned bony fishes (actinopterygians), electroreception was lost in the radiation leading to the neopterygian clade, i.e., holostean fishes16 (gars, bowfins) and teleosts, but subsequently evolved independently at least twice in several teleost groups, e.g. catfishes (siluriforms), knifefishes (gymnotiforms) and elephantnose fishes (mormyriforms)5,13,14,17.

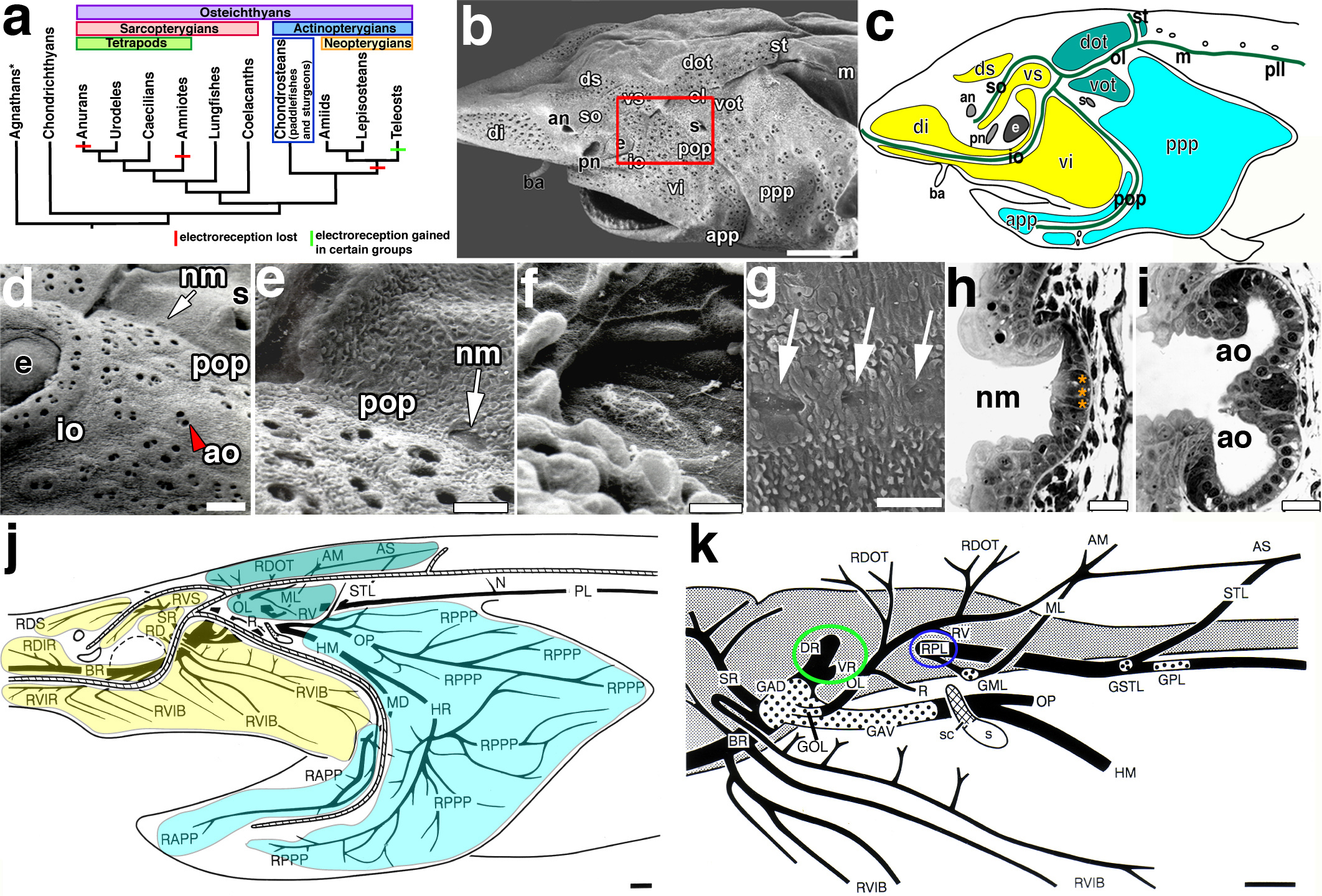

Figure 1. Lateral line system of juvenile paddlefish (Polyodon spathula).

(a) Simplified vertebrate phylogeny illustrating the distribution of electroreception within the major vertebrate clades and the position of chondrosteans, which includes paddlefishes and sturgeons (blue box). Red bars: loss of electroreception; green bars: teleost groups that independently evolved electroreception. *Hagfishes are not electroreceptive. (b, c) SEM and schematic, respectively, of a juvenile paddlefish showing the distribution of the mechanoreceptive neuromast canals and electroreceptive ampullary organ fields. In b, ampullary organ fields are grouped by different colours based on their innervation patterns (see panel j). (d) Magnification of boxed area in b. Red arrowhead: surface pore of an ampullary organ; arrow: a neuromast recessed in a canal. (e) Magnification of neuromast (arrow) within the preopercular canal and (f) of the neuromast itself showing kinocilia on the apical surface. (g) Lateral view of posterior lateral line trunk neuromasts (arrows). (h) Transverse section through a neuromast. Black arrowhead: kinocilia; asterisks: central sensory cells. (i) Transverse section through an ampullary organ cluster containing two organs (round nuclei: sensory cells in epithelium). (j) Schematic reconstruction of head and anterior trunk lateral line nerves based on Sudan Black-stained specimens. Diagonal hatching: neuromast sensory canal lines. The three pre-otic ganglia and associated nerves innervate distinct ampullary organ fields: GAD innervates the ds, vs, di, vi fields (yellow); GAV innervates the app and ppp fields (turquoise); GOL innervates the dot and vot fields (teal). (k) Schematic of the brain and lateral line ganglia (dotted areas) and associated nerves based on Sudan Black-stained specimens, sectioned material and an osmicated dissection of juvenile cranial nerves. Circles highlight the roots of pre-otic (green) and post-otic (blue) afferents. Scale bars: 1 mm (b, j, k), 200 μm (d), 100 μm (e, g), 10 μm (f), 25 μm (h, i). Abbreviations: AM, anastomosis of otic ramus of anterodorsal lateral line nerve with middle lateral line nerve; an, anterior naris; ao, ampullary organ; app, anterior preopercular ampullary field; AS, anastomosis of otic ramus of anterodorsal lateral line nerve with middle lateral line nerve and supratemporal ramus of posterior lateral line nerve; ba, barbel; BR, buccal ramus of anterodorsal lateral line nerve; dot, dorsal otic ampullary field; di, dorsal infraorbital ampullary field; DR, dorsal root of anterior lateral line nerves; ds, dorsal supraorbital ampullary field; e, eye; GAD, ganglion of anterodorsal lateral line nerve; GAV, ganglion of anteroventral lateral line nerve; GML, ganglion of middle lateral line nerve; GOL, ganglion of otic lateral line nerve; GPL, ganglion of posterior lateral line nerve; GST, ganglion of supratemporal lateral line nerve; HM, hyomandibular trunk (mixed trunk with large component of anteroventral lateral line fibres); HR, hyoid ramus of hyomandibular trunk; io, infraorbital lateral line; m, middle lateral line; MD, external mandibular ramus of hyomandibular trunk; ML, middle lateral line nerve; N, first neuromast ramule of posterior lateral line nerve; nm, neuromast; ol, otic lateral line; OL, otic lateral line nerve; OP, opercular ramus of hyomandibular trunk; PL posterior lateral line nerve; pll, posterior lateral line; pn, posterior naris; pop, preopercular lateral line; ppp, posterior preopercular field; R, ramule to spiracular organ; RAPP, ramule to ampullary organs of anterior preopercular field; RD, ramule to dorsal infraorbital field posterior to eye; RDIR, ramule to dorsal infraorbital field on rostrum; RDOT, ramule to dorsal otic field; RDS, ramule to dorsal supraorbital field; RPL, root of post-otic lateral line nerves; RPPP, ramule to posterior preopercular field; RV, ramule to ventral otic field; RVIB, ramule to ventral infraorbital field on upper jaw; RVIR, ramule to ventral infraorbital field on rostrum; RVS, ramule to ventral supraorbital field; s, spiracle; sc, spiracular chamber; so, supraorbital lateral line; SR, superficial ophthalmic ramus of anterodorsal lateral line nerve; st, supratemporal lateral line; ST, supratemporal lateral line nerve; vi, ventral infraorbital field; vot, ventral otic field; VR, ventral root of anterior lateral line nerves; vs, ventral supraorbital field.

Neuromasts, and the afferent neurons for both neuromasts and ampullary organs, develop from cranial lateral line placodes, i.e., paired patches of thickened head ectoderm (primitively, three pre-otic and three post-otic placodes5,8,15). Neurons delaminate from one pole of each placode18-20 and collect (with neural crest-derived glia) to form a cranial lateral line ganglion; the other pole forms a primordium that elongates or migrates over the head or trunk, tracked by axons of lateral line neurons, and deposits a line of neuromasts5,6,9,11. Ampullary organ development is much less well understood, at least partly because the main model systems for studying lateral line development (i.e., the teleost zebrafish and the frog Xenopus) are from lineages that have lost the electrosensory subdivision (Fig. 1a). Grafting and ablation studies in the urodele amphibian Ambystoma mexicanum (axolotl), provided clear experimental evidence that lateral line placodes form both ampullary organs and neuromasts in sarcopterygians21,22. In contrast, a neural crest origin for ampullary organs was proposed (based on gene expression data alone) for a cartilaginous fish, the shark Scyliorhinus canicula23, while lateral line axons have been suggested to induce electroreceptors from local ectoderm in an electroreceptive teleost, the catfish Silurus glanis24 (also see ref.25). Before we can hope to understand the extent to which the mechanisms underlying electrosensory and mechanosensory hair cell development are conserved, and the extent to which the mechanisms underlying electrosensory hair cell development are conserved across different taxa, it is essential to define their embryonic origins experimentally in phylogenetically informative taxa.

The North American paddlefish, Polyodon spathula, is a basal actinopterygian fish with easily the largest number of ampullary organs of any living vertebrate species: 50,000-70,000 ampullae per adult26,27. The characteristic rostrum, or paddle (an extension of the cranium), is covered in ampullary organs and used as an electrosensory “antenna” for feeding28,29. Paddlefishes and sturgeons together comprise the chondrosteans30-34, the sister group to the neopterygian clade (gars, bowfins, teleosts) whose ancestors lost the electrosensory subdivision of the lateral line system (but within which specific teleost groups independently evolved electroreceptors) (Fig. 1a). Here, we provide an embryological, molecular and experimental analysis of lateral line development in Polyodon. We show that multiple members of the eyes absent/Eya and sine oculis/Six gene families (characteristic placode markers in all vertebrates35) are expressed throughout lateral line placode development and in both ampullary organs and neuromasts. Using in vivo fate mapping (the first such data reported for any electroreceptive actinopterygian fish), we experimentally demonstrate a lateral line placode origin for ampullary organs as well as neuromasts. Together with previously published data showing a lateral line placodal origin for sarcopterygian ampullary organs22, our findings strongly support an ancestral lateral line placode origin for ampullary organs in all bony fish. Because all available evidence suggests that the ampullary organs found in sarcopterygians and basal actinopterygians are homologous to the ampullae of Lorenzini of chondrichthyan elasmobranchs (sharks and rays)5,13,14, our data also support the hypothesis that ampullary organs are primitively derived from lateral line placodes in all jawed vertebrates.

Results

The lateral line system in juvenile paddlefish

The organization of the mechanosensory and electrosensory divisions of the lateral line was clear in scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of an early juvenile paddlefish (~14 days post-staging, dps) (Fig. 1b, c). In general, the neuromast canals followed a similar pattern to that observed in other gnathostomes. We adopted the following terminology to refer to the lines: supraorbital, infraorbital, otic, preopercular, middle, supratemporal, and posterior (Fig. 1c). A derived condition of the preopercular line in Polyodon (as compared with other chondrosteans7) is that it joins the infraorbital line ventral to the spiracle, instead of joining the otic line posterior to the spiracle. Ampullary organs are confined to the head, and most numerous on the rostrum and opercular flap. Fields of ampullary organs flank the supraorbital, infraorbital, otic and preopercular lines: these fields were named primarily according to their innervation pattern (see below) and position adjacent to specific canals, e.g., the dorsal infraorbital and ventral infraorbital fields flank the infraorbital canal, while the anterior preopercular and posterior preopercular fields flank the preopercular canal (Fig. 1c).

The pores of ampullary organ clusters were clearly seen on the surface, while the neuromasts were recessed in canals (Fig. 1d). Individual neuromasts were identifiable within the canals (Fig. 1e) by their morphology and characteristic protrusions of kinocilia from the apical surfaces of the sensory hair cells (Fig. 1f). Individual neuromasts of the posterior trunk line were also easily distinguishable (Fig. 1g). Transverse sections revealed the organization of the sensory receptor cells within the different organs (Fig. 1h,i). In neuromasts, the sensory hair cells (three in this section) were located in the centre of the organ, where kinocilia could be observed on the apical surface (Fig. 1h). In ampullary organ clusters, a larger number of sensory cells (large, round nuclei) were organized as an epithelium with support cells wedged between them (Fig. 1i), consistent with previous anatomical descriptions27. Neuromasts appeared smaller than the ampullary organs by this point in development.

Sudan Black staining of whole specimens (ranging from late larval to juvenile stages, plus analysis of sectioned material and an osmicated dissection of juvenile cranial nerves) enabled reconstruction of the lateral line ganglia and nerves of the head and anterior trunk and the innervation patterns of the neuromast canals and ampullary organ fields (Fig. 1k,j). Three of the lateral line ganglia are pre-otic, and three are post-otic, a generally conserved feature found across the osteichthyans5,36. Anteriorly, the anterodorsal lateral line ganglion and nerve innervate the neuromasts of the supraorbital and infraorbital lines and their flanking fields of ampullary organs (Fig. 1j). This is the largest lateral line ganglion because of the very large number of ampullary organs in these fields. Closely adjoining the anterodorsal ganglion is the much smaller otic lateral line ganglion and nerve, which innervates neuromasts of the otic lateral line and its flanking fields of ampullary organs, as well as the spiracular organ, a specialised mechanosensory lateral line organ located in a recess dorsal to the spiracle (Fig. 1j). The anteroventral lateral line ganglion and nerve innervate the neuromasts of the preopercular canal and its flanking fields of ampullary organs. There are so many ampullary organs on the operculum that the anteroventral lateral line ganglion and nerve are the second-largest component of the lateral line system. The anterodorsal and anteroventral ganglia are also closely associated (Fig. 1k). The pre-otic lateral line nerves send a dorsal root to enter the brain at the level of the dorsal octavolateral nucleus (associated with electroreception) and a ventral root to enter at the level of the medial octavolateral nucleus (associated with mechanoreception) (both roots circled in green in Fig. 1k). In contrast, the three post-otic lateral line nerves (middle, supratemporal and posterior) which respectively innervate the neuromasts of the middle, supratemporal and posterior canals (which lack flanking fields of ampullary organs), only send a common root (circled in blue in Fig. 1k) into the brain at the level of the medial octavolateral nucleus, suggesting these are only associated with mechanoreception.

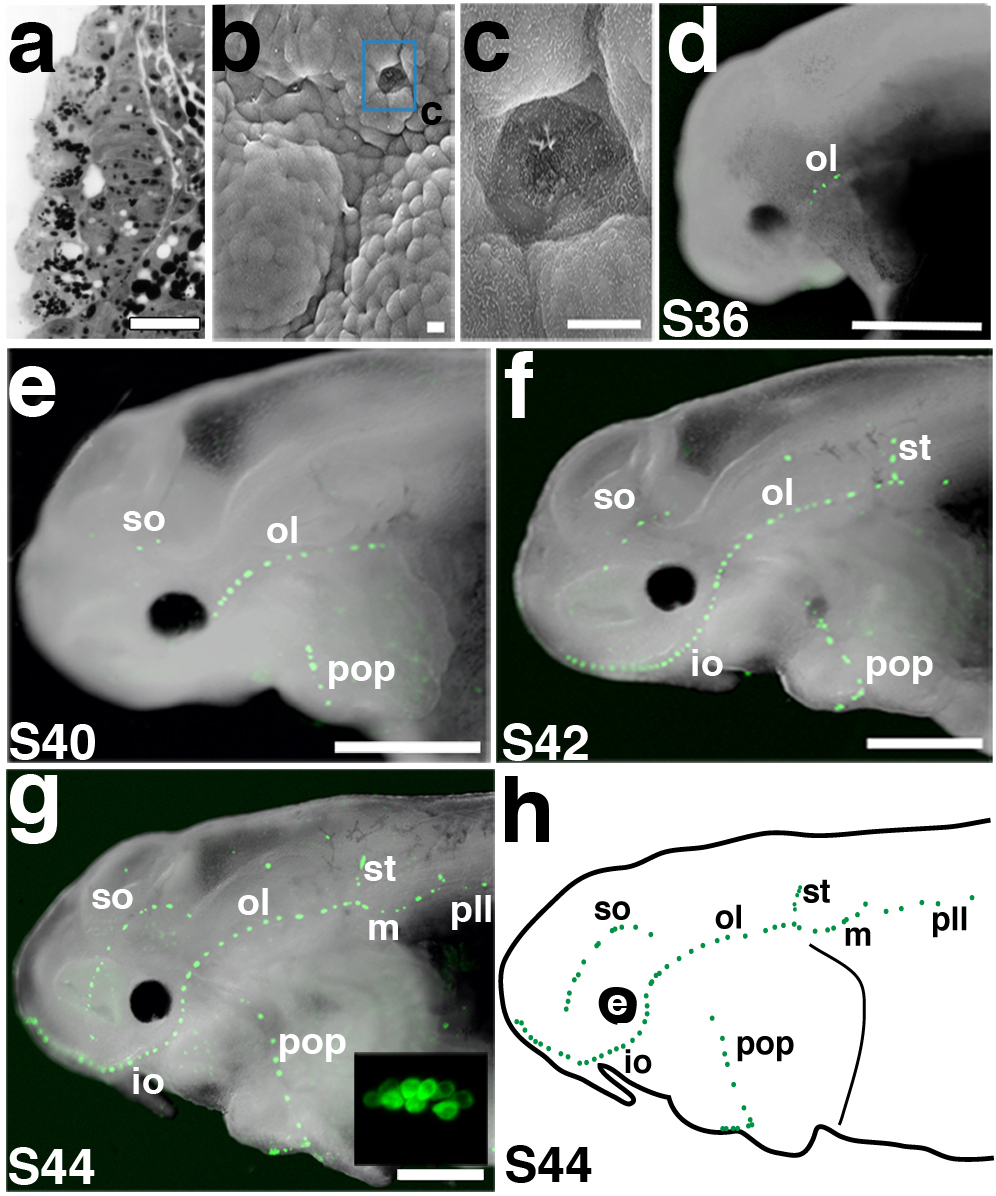

Spatiotemporal development of functional neuromasts

Primordial neuromasts developing from the inner layer of ectoderm were observed on sections at stage 32 (Fig. 2a), but SEM revealed the emergence of the first neuromasts through the epidermal layer at stage 33 in the otic lateral line canal (Fig. 2b,c). We also followed neuromast development in live embryos using FM1-43, a voltage-sensitive fluorescent styryl dye that is internalized (putatively via mechanosensitive ion channels) by mechanosensory hair cells of the inner ear and lateral line37. Consistent with the SEM data, the first lateral line hair cell clusters visible with FM1-43 were within neuromasts of the otic lateral line canal (Fig. 2d): at stage 36, three to four FM1-43-positive hair cell clusters were observed. By stage 40, supraorbital and preopercular canal line neuromasts were also evident (Fig. 2e). FM1-43-positive neuromasts progressively emerged in both directions along the anterior-posterior axis. By stage 42, supratemporal and middle canal line neuromasts were FM1-43-positive (Fig. 2f). By stage 44, all neuromast canal lines contained FM1-43-positive hair cell clusters, including the posterior line, in which the clusters appeared in an anterior to posterior progression along the main trunk line (Fig. 2g,g′). At this stage there were approximately 10-12 hair cells per cluster (Fig. 2g, inset). FM1-43 uptake was never seen in ampullary organs, consistent with the proposed uptake of FM1-43 via mechanosensory ion channels37, which may therefore be absent in electrosensory hair cells.

Figure 2. Spatiotemporal development of functional neuromasts.

(a) Transverse section through a neuromast primordium developing in the otic lateral line placode at stage 31/32. (b) SEM of a stage 33 embryo showing the first neuromast to erupt (blue box), in the otic lateral line. (c) Magnification of erupted neuromast in b. (d-g) Fluorescent images superimposed on darkfield images of embryos labelled with FM1-43 (green) from stages 36 through 44. Anterior to left. (d) Stage 36 embryo showing the first functional neuromasts in the otic lateral line (ol). (e) Stage 40 embryo showing FM1-43-positive cells in the neuromasts of the supraorbital (so), infraorbital (io) and preopercular (pop) lines. (f) Stage 42 embryo showing neuromasts of the middle (m) and supratemporal (st) lines. (g) Stage 44 embryo. All neuromast lines are present, including the posterior lateral line (pll). Inset: magnification of FM1-43-positive hair cell cluster, showing approximately 10-12 hair cells. (h) Schematic of a stage 44 embryo showing all the neuromast canal lines. Scale bars: 25 μm (a), 10 μm (b, c), 1 mm (d-g). Abbreviations: e, eye; io, infraorbital lateral line; m, middle lateral line; ol; otic lateral line; pll, posterior lateral line; pop, preopercular lateral line; S, stage; so, supraorbital lateral line; st, supratemporal lateral line.

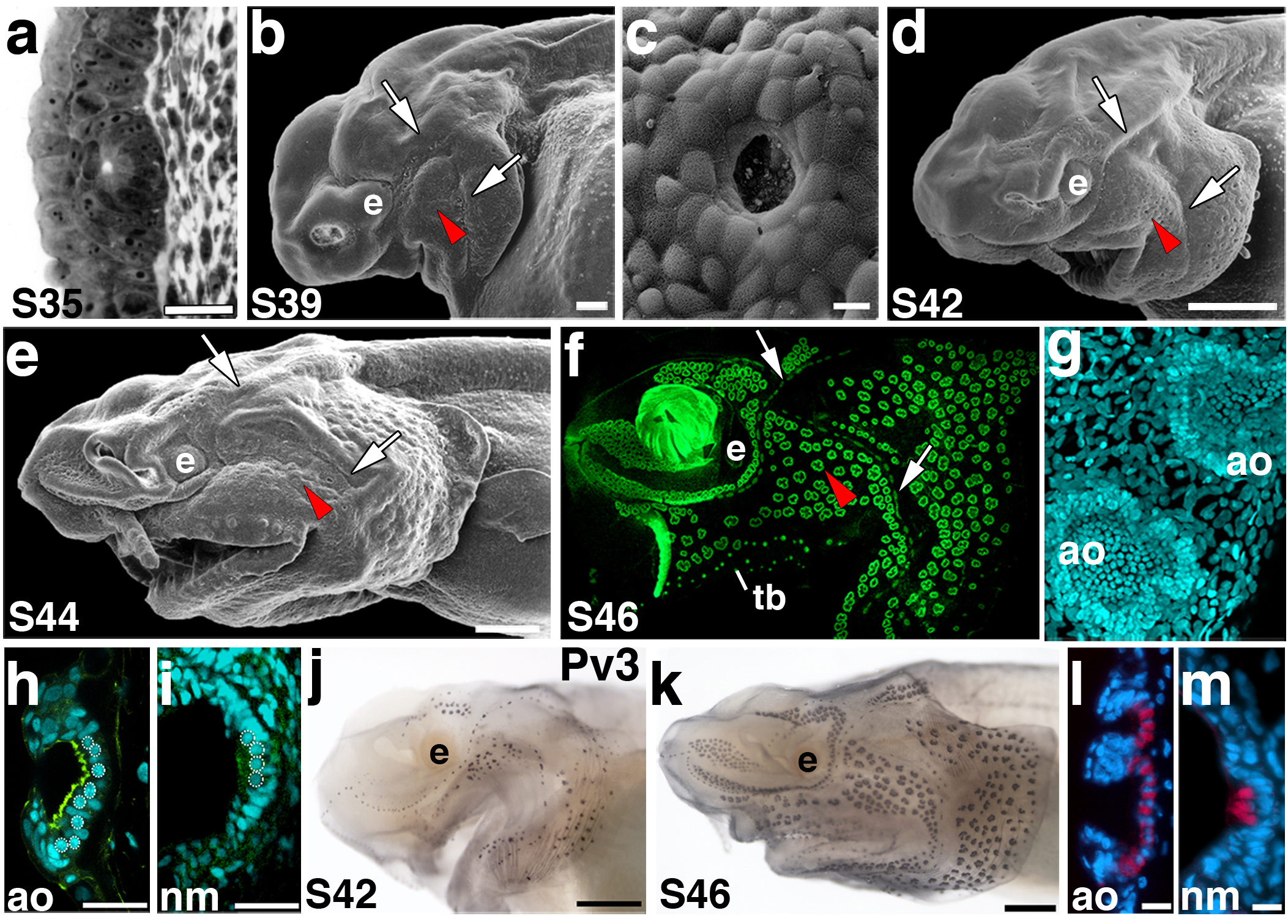

Development of ampullary organ fields

Primordial ampullary organs beneath the epidermis were seen on sections at stage 35 (Fig. 3a; for comparison with a neuromast, see Fig. 2a), but SEM analysis showed that the first ampullary organs to open to the surface only emerged at approximately stage 39 (well after hatching, at stage 36), mainly on the operculum (Fig. 3b,c), after which the number of open ampullary organs rapidly increased. By stage 42, ampullary organs had begun to erupt from all fields (Fig. 3d). By stage 44, nearly all ampullary organs were open to the surface and fully differentiated (Fig. 3e). Ampullary organ fields and neuromast canals were beautifully revealed at stage 46 (the start of feeding) by staining skin mounts with the nuclear markers Sytox Green (Fig. 3f) and DAPI (Fig. 3g). Confocal images of DAPI-stained ampullary organs from the surface (Fig. 3g) and in transverse section (Fig. 3h) showed the shallow depth of paddlefish ampullary organs and the large number of sensory cells lining the epithelium (in comparison to a neuromast which has fewer sensory cells; Fig. 3i). Staining for the F-actin marker phalloidin also highlighted the microvilli (stereocilia) on the apical surface of the ampullary organ sensory epithelium (Fig. 3h). Immunostaining in both whole mount (Fig. 3j,k) and on sections (Fig. 3l,m) revealed that parvalbumin-3 (Pv3), a Ca2+-binding protein thought to be the major calcium buffer in inner ear and lateral line mechanosensory hair cells38, is also expressed in electrosensory hair cells.

Figure 3. Ampullary organ development.

Anterior to left; lateral views unless otherwise noted. (a) Transverse section through an ampullary organ primordium at stage 35. (b) SEM of a stage 39 embryo. Ampullary organs have erupted through the surface in several fields, in particular on the opercular flap. The red arrowheads in panels b-f indicate approximately the same region of ampullary organs that are erupting or have erupted at the different stages of development. The arrows indicate neuromast canal lines, specifically of the otic and preopercular lines. (c) SEM showing a surface view through the pore of a newly erupted ampullary organ. (d) SEM of a stage 42 embryo. Ampullary organs appear to have erupted from all fields by this stage. (e) SEM of a stage 44 embryo showing further differentiation of the ampullary organ fields. (f) Fluorescent image of a stage 46 embryo skin mount, stained with the nuclear marker Sytox Green. Individual clusters of ampullary organs are discernable, as are the neuromast canal lines. (g,h) Confocal images of ampullary organs stained with the nuclear marker DAPI in (g) surface view and (h) transverse view. The F-actin marker phalloidin (green) labels the microvilli-enriched apical surface. (i) Confocal image of a neuromast in transverse view at the same stage for comparison with h. In h and i, the round nuclei of sensory cells are outlined. (j) Stage 42 embryo stained for parvalbumin-3 (Pv3). Hair cells within both neuromasts and ampullary organs express this Ca2+-binding protein. (k) Stage 46 embryo stained for parvalbumin-3. Pv3 is strongly expressed in all lateral line sensory organs. (l, m) False colour overlay with DAPI images, respectively, of transverse sections through ampullary organs and a neuromast. Pv-3 (red in l, m) specifically labels the sensory hair cells in both ampullary organs and neuromasts. Scale bars: 25 μm (a), 100 μm (b), 10 μm (c, l, m), 500 μm (d, e, j, k), 30 μm (h, i). Abbreviations: ao, ampullary organ; e, eye; S, stage; tb, taste bud.

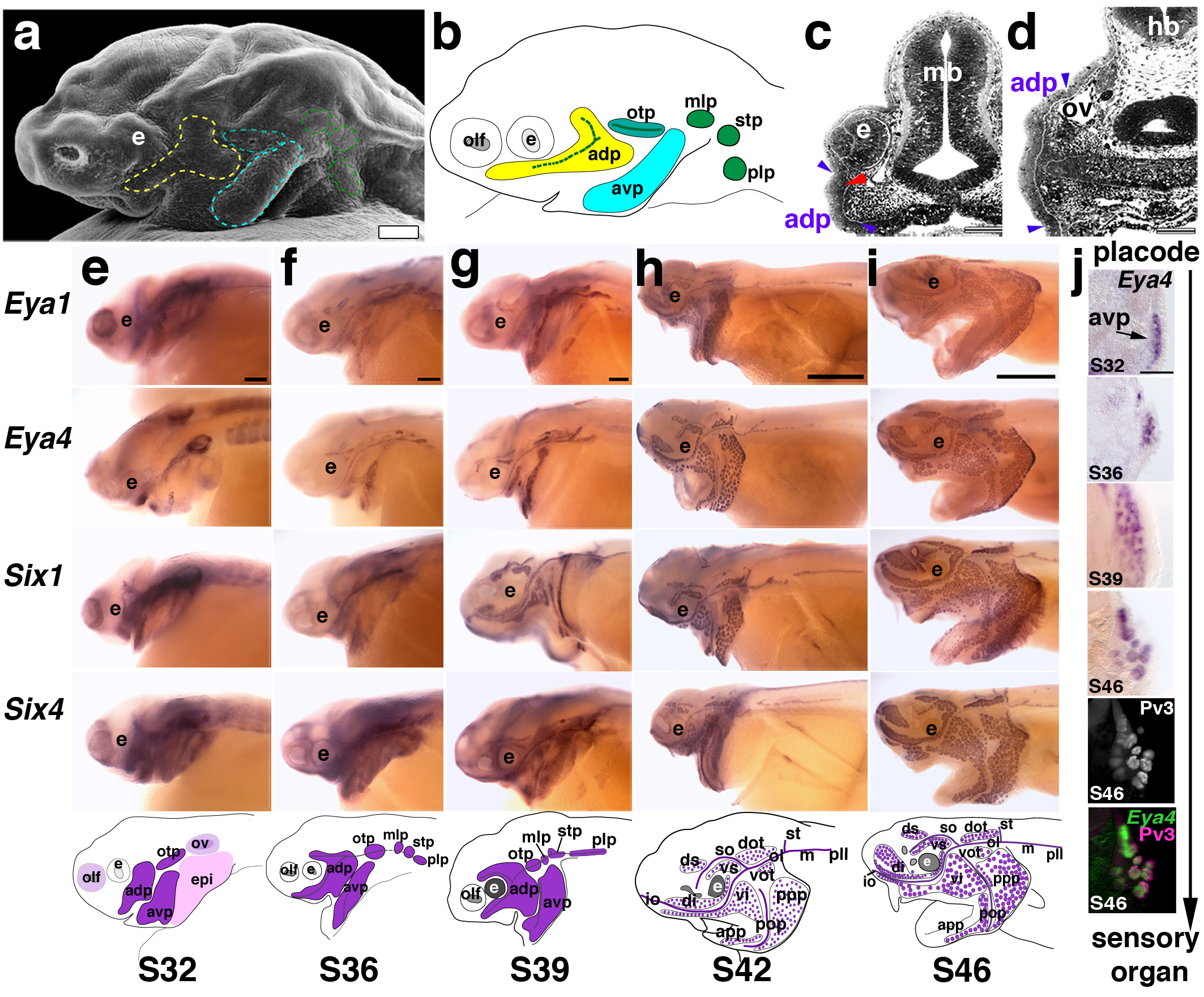

Development of lateral line placodes

Using SEM and reconstructions of histological sections, lateral line placodes were first discernable around stage 25, and well developed by stage 32 (Fig. 4a; summarized schematically in Fig. 4b). Although the boundaries of individual placodes were difficult to distinguish precisely, we recognized three pre-otic lateral line placodes (anterodorsal, anteroventral and otic) and three post-otic lateral line placodes (middle, supratemporal and posterior) (Fig. 4a,b). This is consistent with sturgeons7, and thought to be the primitive condition for jawed vertebrates5. The first lateral line placode to be morphologically discernable was the otic, consistent with the appearance of the first neuromasts in the otic lateral line canal (see Fig. 2). The largest lateral line placode was the anterodorsal, which formed a visible bulge in SEM, ventral and slightly posterior to the eye (Fig. 4a). The anteroventral placode, located ventral and posterior to the anterodorsal placode, was the second largest lateral line placode; the three post-otic placodes (middle, supratemporal and posterior) were the smallest. Sample sections through the anterodorsal placode showed the extent of the thickened epithelium, extending from the level of the developing eye (Fig.4c) to the otic vesicle (Fig. 4d). At stage 32, the placodes were already beginning to elongate or spread over the head to form sensory ridges and neuromast primordia were beginning to differentiate from the central zones of these ridges (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Expression of Eya and Six family members during lateral line development.

(a) SEM of a stage 32 embryo. Placodes (outlined) are visible surface bulges. (b) Schematic summarizing histological serial reconstructions at stage 32 of the three pre-otic (anterodorsal [yellow], anteroventral [turquoise], otic [teal]) and three post-otic lateral line placodes (middle, supratemporal, posterior [green]). (c, d) Transverse sections through the anterodorsal placode at the level of the eye (c) and otic vesicle (d). Blue arrowheads indicate extent of thickened epithelium (i.e., the placode). Red arrowhead indicates a developing neuromast primordium. (e-i) Whole-mount in situ hybridisations for Eya1, Eya4, Six1 and Six4 from stages 32-46; schematics show the general expression pattern at those stages. Lateral views; anterior is left. (e) At stage 32, Eya1, Six1 and Six4 are expressed in multiple placodes including olfactory and otic (purple), epibranchial (pink), and lateral line (dark purple); strong expression of Eya4 is restricted to lateral line placodes and the otic vesicle. By this stage, the lateral line placodes have started to elongate or spread along the head. (f) At stage 36, all genes are expressed in developing neuromast canal lines and presumptive ampullary organ fields flanking those lines. (g) At stage 39, expression of all genes continues in elongating lateral line primordia and neuromast canals. Individual ampullary organ fields start to be identifiable. At (h) stage 42 and (i) stage 46, expression of all genes continues in developing lateral line organs as well as in the migrating posterior lateral line primordium. (j) Transverse sections showing Eya4 expression in the developing anterior ventral placode (avp) from stages 32-46. By stage 46, the hair cell marker Pv3 (grey-scale image) overlaps with Eya4 as shown in the false-colour overlay of Eya4 (green) and Pv3 (pink). Scale bars: 100 μm (a, c, d, j), 200 μm (e-i). Abbreviations: adp, anterodorsal placode; avp, anteroventral placode; e, eye; epi, epibranchial placode region; hb, hindbrain; mb, midbrain; mlp, middle lateral line placode; olf, olfactory; otp, otic lateral line placode; ov, otic vesicle; plp, posterior lateral line placode; S, stage; stp, supratemporal placode.

Lateral line expression of Eya and Six family members

Cranial placodes originate from a common “pre-placodal region” or “pan-placodal primordium”, characterised by expression of members of the Eya, Six1/2, and Six4/5 families of transcription factors or co-factors, whose expression is maintained in all cranial placodes and their derivatives12,39. Zebrafish Eya1 is expressed in lateral line placodes and neuromasts20, while shark Eya4 is expressed in lateral line placodes, neuromasts and ampullary organs40, making these excellent candidate markers for the developing lateral line system in paddlefish. We used degenerate PCR to clone paddlefish Eya1-4, Six1, Six2 and Six4, and examined their expression by in situ hybridisation. All seven genes were expressed in lateral line placodes, neuromasts and ampullary organs. We present data for Eya1, Eya4, Six1 and Six4 in Fig. 4e-j; Eya2, Eya3 and Six2 were similarly expressed.

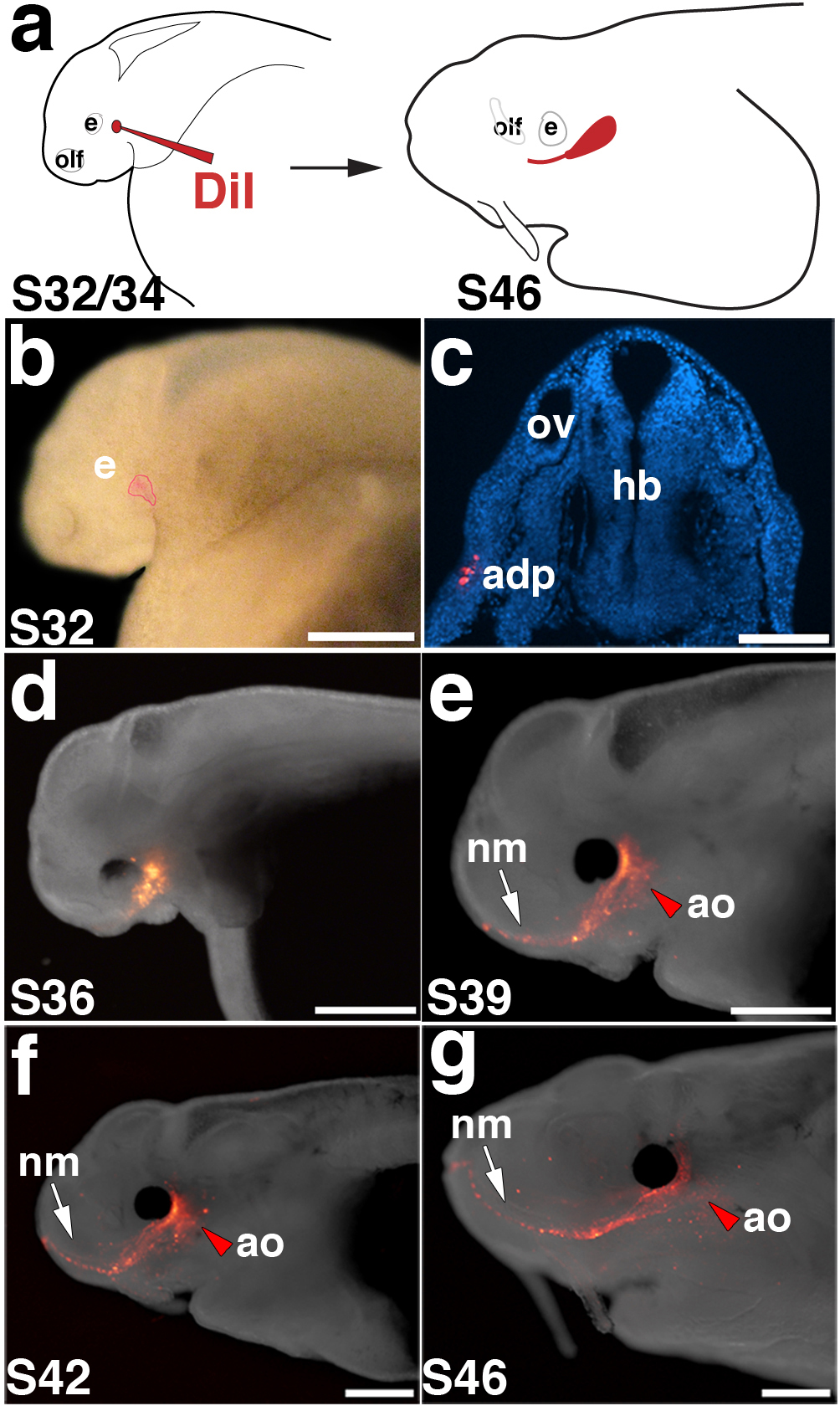

Figure 5. In vivo labelling of lateral line placodes.

(a) Schematic of in vivo labelling experimental design. Embryos are focally injected with DiI between stage 32 and 34 and followed to stage 46. (b) Stage 32 embryo immediately after focal injection with DiI. In this example, the anterodorsal placode (outlined in red) was labelled. (c) Transverse section through another stage 32 embryo immediately after injection, showing DiI-positive cells (red; DAPI in blue) in the anterodorsal placode. (d-g) Fluorescent images superimposed on darkfield images of the same embryo shown in panel b, at successive stages of development. (d) Stage 36. (e) Stage 39. (f) Stage 42. (g) Stage 46. As development progresses, DiI spreads anteriorly from the site of injection as neuromasts of the infraorbital line (arrow) are deposited. Ampullary organs (red arrowhead) are also labelled near the site of injection. Scale bars: 500 μm (b), 100 μm (c), 1 mm (d-g). Abbreviations: adp, anterodorsal lateral line placode; e, eye; hb, hindbrain; olf, olfactory; ov, otic vesicle; S, stage.

At stage 32, Eya1, Six1 and Six4 (Fig. 4e) were all expressed in multiple placodes, including the otic vesicle, olfactory placode, epibranchial placodes and lateral line placodes, where their expression patterns were consistent with the elongation and spreading of lateral line primordia to form sensory ridges. In contrast, Eya4 expression was specific to the otic vesicle and the elongating lateral line placodes (Fig. 4e). At stage 36, placodal expression of all these genes was maintained, although at weaker levels, and individual neuromast canal lines could be distinguished (Fig. 4f). By stage 39, expression was seen in all neuromast lines and revealed the formation of ampullary organ fields (Fig. 4g); by stage 42, individual ampullary organs could be seen (Fig. 4h). At stage 46, expression was maintained in both neuromasts and ampullary organs (Fig. 4i). The overall expression pattern of these genes was consistent with our morphological reconstructions of lateral line placodes. Analysis of sections at different stages showed that patches of placodal tissue progressively lose expression, while the regions that give rise to the organs retain expression (Fig. 4j). Expression of all seven genes in ampullary organs, as well as in neuromasts and lateral line placodes, supports the hypothesis that ampullary organs in this basal ray-finned fish are lateral line placode-derived. However, gene expression data alone cannot be taken as proof of cell lineage.

Paddlefish lateral line placodes generate ampullary organs

Our analysis of paddlefish lateral line development by SEM, reconstruction of histological sections, as well as Eya and Six gene expression and innervation patterns, together suggest that pre-otic lateral line placodes form both neuromast canal lines and their flanking fields of ampullary organs. (In contrast, the post-otic placodes seem only to give rise to neuromasts and their associated nerves; this is also consistent with the observed size difference of the individual placodes.) To test the hypothesis that ampullary organs, as well as neuromasts, are lateral line placode-derived in paddlefish, we focally labelled the two largest lateral line placodes (anterodorsal and anteroventral) with the fluorescent lipophilic dye DiI at stages 32-34 and followed their development through stage 46 (see Fig. 5a, c). Examples are shown in Figures 5 and 6.

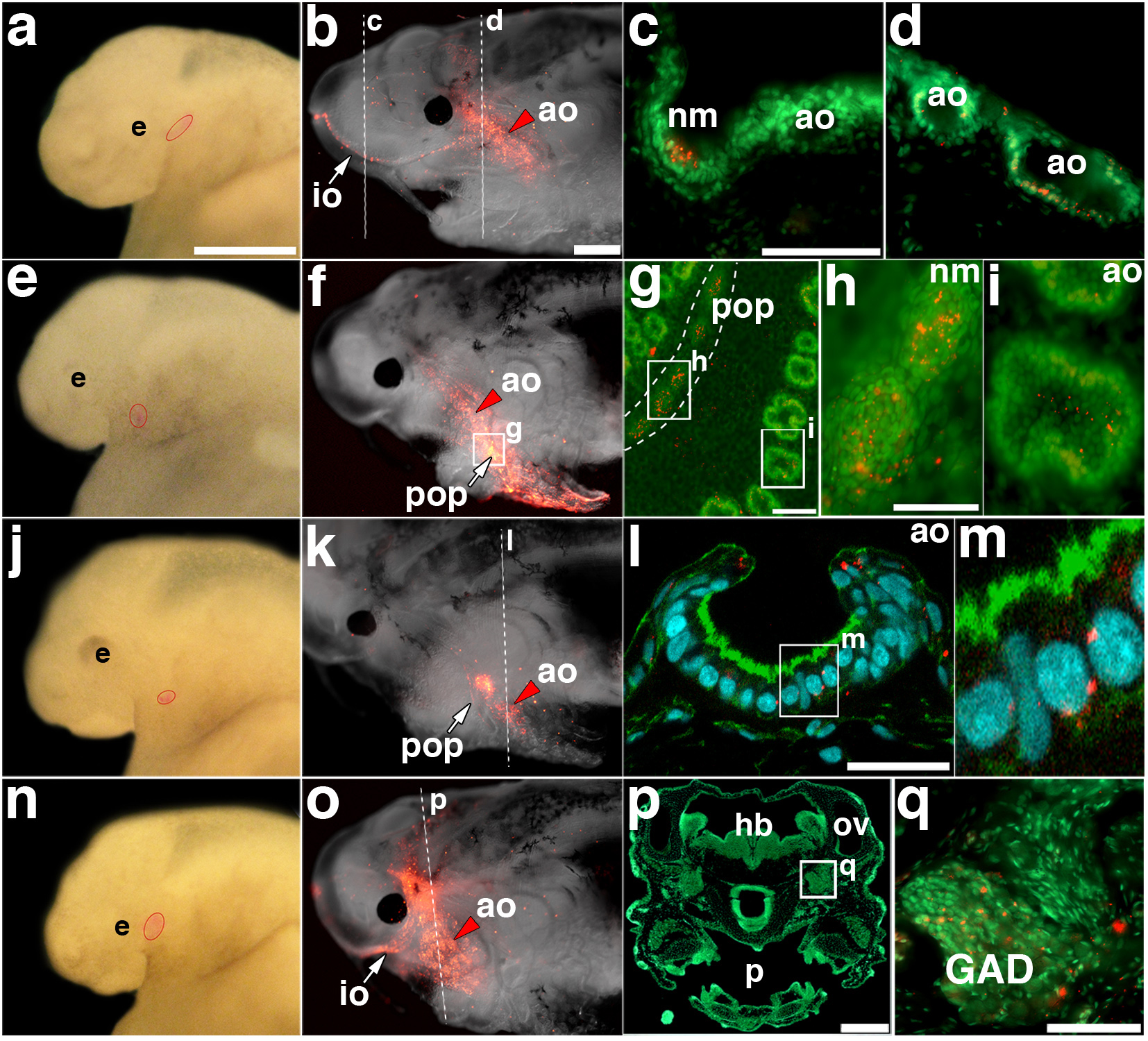

Figure 6. Lateral line placodes give rise to ampullary organs and neuromasts.

(a) Stage 32 embryo after focal injection with DiI in the anterodorsal placode; injection site outlined in red. (b) Same embryo at stage 46, showing DiI-labelled cells in the infraorbital neuromasts and dorsal infraorbital and ventral infraorbital ampullary organ fields. (c, d) Transverse sections through (c) a DiI (red)-labelled neuromast and (d) DiI-labelled ampullary organs, counterstained with Sytox Green. (e) Stage 32 embryo after focal injection with DiI in the anteroventral placode; injection site outlined in red. (f) Same embryo at stage 46, showing DiI-labelled cells in preopercular neuromasts and flanking ampullary organs. (g) Opercular skin mount from embryo in (f), counterstained with Sytox Green, showing DiI in preopercular neuromasts and flanking ampullary organs. (h) Magnification of DiI-labelled neuromasts from preopercular neuromast line in (g). (i) Magnification of DiI-labelled ampullary organ from posterior preopercular field in (g). The plane of focus is the sensory cell epithelium. (j) Stage 34 embryo after focal injection with DiI in the anteroventral placode; injection site outlined in red. (k) Same embryo at stage 46, showing DiI-labelled cells in a subset of preopercular neuromasts and flanking ampullary organs. (l) Confocal image of transverse section from embryo in (k), stained with phalloidin (green) and DAPI (blue), showing a DiI (red)-labelled ampullary organ. (m) Magnification from (l), showing DiI (red) within the sensory epithelium. (n) Stage 32 embryo after focal injection with DiI in the anterodorsal placode; injection site outlined in red. (o) Same embryo at stage 46, showing DiI-labelled cells in infraorbital line neuromasts and flanking ampullary organs. (p) Transverse section through head of embryo in (o), stained with Sytox Green. (q) Magnification from (p) showing DiI-labelled cells (red) in the anterodorsal lateral line ganglion. Scale bars: 500 μm (a, e, j, n), 1 mm (b, f, k, o), 50 μm (c, d, h, i, q), 100 μm (g), 30 μm (l), 250 μm (p). Abbreviations: ao, ampullary organ; e, eye; GAD, anterodorsal lateral line ganglion; hb, hindbrain; io, infraorbital lateral line; nm, neuromast; ov, otic vesicle; p, pharynx; pop, preopercular lateral line.

In the embryo shown in Fig. 5b, Di-labelled cells in the anterodorsal placode ultimately contributed to the infraorbital neuromast canal line as well as to ampullary organs in the ventral infraorbital field adjacent to the eye (Fig. 5g). Imaging the same embryo at successive stages revealed the elongation and spreading of DiI-labelled cells (Fig. 5d-g). Fig. 6 shows four additional examples of placode labelling experiments (two anterodorsal, two anteroventral). Transverse sections through an embryo after labelling the anterodorsal placode (Fig. 6a,b) showed DiI in individual infraorbital canal neuromasts (Fig. 6c) and ampullary organs in the flanking fields (Fig. 6d). In the embryo shown in Fig. 6e, DiI-labelled anteroventral placode cells contributed to preopercular canal neuromasts and flanking ampullary organs (Fig. 6f). After isolating the operculum, counterstaining with Sytox Green and flatmounting the sample (Fig. 6g), DiI was clearly observed in both neuromasts (Fig. 6h) and ampullary organs (Fig. 6i). In another labelled embryo (Fig. 6j,k), confocal imaging of transverse sections revealed DiI-positive cells within the ampullary organ sensory epithelium (Fig. 6l,m). Sectioning in some cases also revealed DiI in the lateral line ganglia, as expected since neurons in these ganglia are lateral line placode-derived18-20. In the example shown in Fig. 6n, DiI-labelled anterodorsal placode cells contributed not only to infraorbital and supraorbital line neuromasts and flanking fields of ampullary organs (Fig. 6o), but also (as observed on sections) to cells within the anterodorsal lateral line ganglion (Fig. 6p,q).

In total, we successfully labelled ampullary organs in 50 embryos after focally injecting DiI into the anterodorsal or anteroventral placodes between stages 32-34. DiI was seen in neuromasts as well as ampullary organs in 24 of these embryos, confirming successful targeting of lateral line placodes. In the remaining 26 embryos, DiI was only visible in ampullary organs. We suggest that in these cases, the label only targeted the lateral region of the placode, since ampullary organs develop from the lateral zones of lateral line primordia in the axolotl, while neuromasts develop from the central ridges21,22.

Overall, our fate-mapping data confirm that ampullary organs are derived from lateral line placodes in Polyodon, an actinopterygian. Taken together with the previous experimental demonstration of a lateral line placodal origin for ampullary organs in the axolotl22, a sarcopterygian, this strongly supports an ancestral lateral line placodal origin for ampullary organs in all bony fishes.

Discussion

Our morphological, molecular and in vivo fate-mapping data demonstrate a lateral placode origin for both electrosensory and mechanosensory divisions of the lateral line system in a basal actinopterygian, the North American paddlefish Polyodon spathula. The developmental origin of electrosensory ampullary organs had previously only been experimentally tested in a sarcopterygian, the axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum, in which grafting and ablation experiments confirmed that individual lateral line placodes form both ampullary organs and neuromasts22. A neural crest origin was recently proposed for ampullary organs in a chondrichthyan, the shark Scyliorhinus canicula23, but this proposition was based on gene expression data alone, which is not sufficient to confirm cell lineages. Lateral line axons were proposed to induce electroreceptor formation from non-placodal ectoderm in a teleost, the catfish Silurus glanis24. However, teleost electroreceptors evolved independently (ampullary organs were lost in the lineage leading to neopterygians5,13,14) and no fate-maps have yet been undertaken in electroreceptive teleosts. Our demonstration that lateral line placodes form ampullary organs and neuromasts in a basal actinopterygian provides the strongest possible support for an ancestral lateral line placode origin for ampullary organs in bony fishes (see phylogeny in Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the homology of ampullary organs between bony fishes and chondrichthyans (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) is supported by all the available evidence: they are excited by cathodal stimuli and innervated by lateral line nerves projecting to a dorsal octavolateral nucleus in the medulla. To this we can now add embryonic expression of Eya4 (paddlefish, this paper; shark40). If this homology is accepted, then our data also support an ancestral lateral line placode origin for ampullary organs in all jawed vertebrates (and perhaps even all vertebrates: although electroreceptor organs in lampreys have a significantly different morphology, they are innervated by a branch of the anterior lateral line nerve and adult lampreys have a dorsal octavolateral nucleus in the medulla4,41,42).

Although a neural crest contribution to neuromasts was reported for both Xenopus (a sarcopterygian) and zebrafish (an actinopterygian) after DiI-labelling presumptive neural crest precursors43, the nature and extent of this contribution has been debated7,19,22,44. For example, these cells may represent neural crest-derived glial cells, which are intimately associated with the lateral line nerves that innervate neuromasts45. It would be useful to re-visit these neural crest labelling experiments using known hair cell markers such as parvalbumin-3.

Almost all the information we have on the molecular mechanisms underlying vertebrate hair cell development, whether in the inner ear or lateral line, has been obtained from a handful of model systems: two amniotes (mouse and chick), the frog Xenopus and the teleost zebrafish. None of these species has electroreceptors, which are modified hair cells with a limited range of morphologies4. Hence, our understanding of the potential range of mechanisms underlying vertebrate hair cell development is very incomplete. The expression during paddlefish lateral line placode development of all Eya, Six1/2, and Six4/5 family members examined, and their maintenance in both neuromasts and ampullary organs, suggests at least some conservation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of these distinct sense organs. Further studies of lateral line development in the paddlefish will enable us to discover the extent to which the mechanisms underlying the development of mechanosensory and electrosensory hair cells are conserved.

Despite having the most ampullary organs of any vertebrate species, Polyodon may also be an excellent model for investigating the possible developmental basis for the evolutionary loss of ampullary organs, as occurred in various groups, including frogs and the lineage leading to the neopterygian clade (gars, bowfins, teleosts)5,13-15. We have shown here that paddlefish ampullary organ formation is restricted to the three pre-otic placodes (anterodorsal, anteroventral, otic): the three post-otic placodes (middle, supratemporal and posterior) only generate neuromasts. In the sturgeon Scaphirhynchus platorynchus (a member of the sister group to paddlefishes within the chondrosteans; Fig. 1a), ampullary organ fields are associated with the three pre-otic lines and also with the supratemporal line7. In the axolotl (a sarcopterygian tetrapod), the pre-otic lines plus the supratemporal and middle lines form ampullary organs21. The strict relationship between each of the six lateral line placodes and their developmental derivatives (placode-nerve-receptor organ line/field) offers support for the theory that these six placodes and their derivatives should be regarded as phylogenetically independent components of the lateral line system, subject to individual modification through evolution. Both the extreme number of ampullary organs derived from the anterodorsal and anteroventral placodes in paddlefish, and the failure of all post-otic lateral line placodes to form ampullary organs in this species, would seem to offer an ideal opportunity to discover direct evidence about the ways in which such evolutionary modification of placodes and their derivatives might occur.

Methods

Embryo collection

Embryos were obtained from Osage Catfisheries, Inc. (Osage Beach, MO, USA) over multiple spawning seasons. Embryos were raised at approximately 22°C in tanks with filtered and recirculating water (pH 7.2±0.7, salinity of 1.0±0.2ppt) to desired stages. Staging was performed according to ref.46.

cDNA synthesis and cloning

RNA from embryos stages 26 to 46 was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and used to generate single strand cDNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The following degenerate primers were used (F, forward; R, reverse): Eya1F: ACGGTTCAAGCTTTACAACC, Eya1R: TGCTACAAGTAATCAAGTTCC; Eya2F: AACCTCCTACCTACAGCAGG, Eya2R: TGGAGTTGATGAGAGTCAGC, Eya3F: AGACCGTGATGGATGAAGC; Eya3R; ATGCATCCGATCGCTTCC, Eya4F: GCATGACAATTCTTAATACTGC, Eya4R: TCACACCAGTGGCCAGGCAGAGG; Six1F: TTCACKCARGARCARGTSGCGTGYGTSTG, Six1R: TGYCKYCKRTTYTTRAACCARTT, Six2F: AGAGGCGATCATGTCAATGC, Six2R: TTGTGGGTGTACCACTCC, Six4F: TCTGTGAGGCTTTGCAGCAAGG, Six4R: GAGTTCAAAGGGTCTGAATTGCC. PCR fragments were cloned into the pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen). Plasmids were purified and sequenced by the Department of Biochemistry DNA Sequencing Facility, University of Cambridge. Sequence results were analyzed using MacVector and BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). We confirmed the orthology of the different Eya and Six family members through a phylogenetic analysis using Bayesian inference (MrBayes347). GenBank accession numbers are as follows: PsEya1 JF949727; PsEya2 JF949728; PsEya3 JF949729; PsEya4 JF949730; PsSix1 JF949731; PsSix2 JF949732; PsSix4 JF949733.

Histology

For plastic sections, embryos were fixed in paraformaldehyde, rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated stepwise in an ethanol series, and embedded using commercially available methylacrylate kits (Polysciences, Inc.) prior to microtome sectioning and processing in 1% Toluidine Blue in sodium borate buffer and 2% Basic Fuchsin in water. Transverse serial sections were cut at 1.5μm unless otherwise noted. The nerves of cleared larval and juvenile whole specimens hole were stained using Sudan Black48. These samples were then dissected and photographed for camera lucida tracings for schematic reconstructions.

Scanning electron microscopy

Embryos were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde followed by dehydration through ethanol, and subsequent processing with dimethoxypropane and CO2 or Freon 113 (1,1,2 trichlorotrifluoroethane) and Freon 13 (chlorotrifluoromethane). Specimens were then mounted and sputter coated with gold palladium alloy (300-400Å thick) and imaged.

FM1-43 staining

Live embryos were immersed in a solution of 3 μM of FM1-43 (Invitrogen) in water for 45 seconds, then immediately rinsed in three changes of water. Embryos were anaesthetised with tricaine prior to imaging.

Dil labelling

Embryos were dechorionated, immobilized and oriented in troughs made in agarose dishes to the approximate width of stage 32 embryos. Embryos between stages 32 and 34 were injected with 0.5-1 μg/μl Cell Tracker-CM-DiI (Invitrogen) diluted in 0.3M sucrose (from a 5 μg/μl stock diluted in ethanol), using a pressure injector. The ectoderm in paddlefish is a stratified epithelium. Therefore, to penetrate the superficial layer of cells, DiI-filled glass capillary needles were gently pushed through the surface ectoderm prior to release of pressure. Embryos were allowed to recover and develop to stage 46. Embryos were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in 20% gelatin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Transverse serial sections were cut at 50-75μm using a vibratome. Sections were counterstained with the nuclear markers Sytox Green or DAPI (Invitrogen) prior to microscopy.

In situ hybridisation and Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS or modified Carnoy’s fixative (6 volumes ethanol: 3 volumes 37% formaldehyde: 1 volume glacial acetic acid) for 12 to 24 hours at 4° C. Embryos were then dehydrated through a methanol or ethanol series and stored at −20° C. Antisense RNA probes were generated using T7 or SP6 polymerases (Roche) and digoxigenin dUTPs (Roche). For in situ hybridization, embryos were rehydrated through a stepwise series into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 (PTw), bleached under strong white light in 0.5% SSC, 10% H2O2, 5% formamide for 30-60 minutes (depending on stage), then rinsed several times in PTw. After treating for 10-15 minutes at room temperature with proteinase K (14-22μg/ml of Roche proteinase K), followed by two rinses in PTw, embryos were fixed again for 1 hour in 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.02% glutaraldehyde, followed by four rinses in PTw. Embryos were then, graded into hybridization solution (1x salt solution [0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM NaH2PO .4H2O, 5 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulphate, 1 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 1x Denhardt’s solution). After pre-hybridizing for at least 3 hours at 70°C, embryos were incubated for at least 18 hours at 70°C with probe diluted in hybridization solution. After four 30-60-minute rinses in wash solution (50% formamide, 1x SSC, 0.1% Tween-20) at 70°C, embryos were graded into MABT (1X maleic acid buffer with 0.1% Tween-20) [10x MAB: 1M maleic acid, 1.5M NaCl, pH 7.5]. After four 30-minute washes in MABT, embryos were blocked in MABT with 20% filtered sheep serum and 2% Boehringer blocking reagent (Roche) for three to four hours at room temperature prior to incubation in 1:2000 dilution of anti-DIG-AP antibody (Roche) overnight at 4°C. Embryos were washed with MABT six times for one hour each at room temperature, and then overnight at 4°C. For the colouration reaction, embryos were rinsed three times in NTMT buffer (0.1M NaCl, 0.1M Tris, pH9.5, 50mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20), prior to incubation in 0.02% of NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium chloride)/BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, toluidine salt) stock solution (Roche) in NTMT until desired signal strength. Embryos were then rinsed in PBS to stop the reaction, post-fixed, if necessary, and then processed for sectioning or graded into 70% glycerol for whole-mount imaging. Embryos were then cryosectioned as described in the following section or sectioned using a vibratome, as described above. For immunohistochemistry, the polyclonal parvalbumin-3 antibody (gift from A. Hudspeth) was used at 1:30,000, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Labs.) used at 1:600. For the histochemical reaction, embryos were incubated in 600 μl of DAB + Ni solution (0.3 mg/ml 3,3′-diaminobenzidine [Sigma] in 1xPBS/0.05% Tween-20 plus 5 μl of an 8% NiCl2 solution) for 5 minutes. The reaction was started by adding H2O2 to a final concentration of 0.03%, and monitored for up to 15 minutes prior to stopping the reaction with 1x PBS/0.1% Tween-20. Embryos were then cleared through a glycerol series into 70% glycerol/PBS.

Sectioning embryos after whole-mount in situ hybridization

After 5 hours’ incubation at room temperature in 5% sucrose in PBS, embryos were placed in 15% sucrose in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. They were transferred into pre-warmed 7.5% gelatin in 15% sucrose in PBS, then incubated overnight at 37°C prior to being embedded in moulds in the appropriate orientation for transverse sectioning. After freezing the gelatin by immersing the moulds in a dry ice and isopentane solution for one minute, the embryos were cryosectioned at 20μm. After 24 hours at room temperature, the slides were incubated for 5 minutes in PBS pre-warmed to 37°C to remove the gelatin, followed by counterstaining with the nuclear marker DAPI (1 ng/ml). Slides were mounted in Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech.).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the BBSRC (BB/F00818X/1 to C.V.H.B.), NIH (NS24869 and NS24669 to R.G.N.), NSF (BRS 8806539 to R.G.N; 8806539, 8901132 and 9119561 to W.E.B.), the Whitehall Foundation (to W.E.B.) and the Tontogany Creek Fund (to W.E.B.). We also thank the Kahrs family (Osage Catfisheries, Inc.), Jerry Hamilton, Kim Graham, Charlie Suppes (Missouri Department of Conservation), Eric Findeis and Sue Commerford.

References

- 1.Coombs S, Montgomery JC. The enigmatic lateral line system. In: Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Comparative Hearing: Fishes and Amphibians. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1999. pp. 319–362. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullock TH, Hopkins CD, Popper AN, Fay RR. Electroreception. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodznick D, Montgomery JC. The physiology of low-frequency electrosensory systems. In: Bullock TH, Hopkins CD, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Electroreception. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 132–153. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jørgensen JM. Morphology of electroreceptive sensory organs. In: Bullock TH, Hopkins CD, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Electroreception. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Northcutt RG. Evolution of gnathostome lateral line ontogenies. Brain Behav. Evol. 1997;50:25–37. doi: 10.1159/000113319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlosser G. Development and evolution of lateral line placodes in amphibians I. Development. Zoology. 2002;105:119–146. doi: 10.1078/0944-2006-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs MA, Northcutt RG. Development of the lateral line system in the shovelnose sturgeon. Brain Behav. Evol. 2004;64:70–84. doi: 10.1159/000079117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbs MA. Lateral line receptors: where do they come from developmentally and where is our research going? Brain Behav. Evol. 2004;64:163–181. doi: 10.1159/000079745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudière C. The lateral line microcosmos. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2118–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.1568407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker CVH, O’Neill P, McCole RB. Lateral line, otic and epibranchial placodes: developmental and evolutionary links? J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2008;310:370–383. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma EY, Raible DW. Signaling pathways regulating zebrafish lateral line development. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:R381–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlosser G. Making senses: development of vertebrate cranial placodes. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;283:129–234. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)83004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullock TH, Bodznick DA, Northcutt RG. The phylogenetic distribution of electroreception: evidence for convergent evolution of a primitive vertebrate sense modality. Brain Res. 1983;287:25–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New JG. The evolution of vertebrate electrosensory systems. Brain Behav. Evol. 1997;50:244–252. doi: 10.1159/000113338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlosser G. Development and evolution of lateral line placodes in amphibians. II. Evolutionary diversification. Zoology. 2002;105:177–193. doi: 10.1078/0944-2006-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grande L. (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Special Publication no. 6).An Empirical Synthetic Pattern Study of Gars (Lepisosteiformes) and Closely Related Species, Based Mostly on Skeletal Anatomy: The Resurrection of Holostei. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alves-Gomes JA. The evolution of electroreception and bioelectrogenesis in teleost fish: a phylogenetic perspective. J. Fish Biol. 2001;58:1489–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone LS. Experiments on the development of the cranial ganglia and the lateral line sense organs in Amblystoma punctatum. J. Exp. Zool. 1922;35:421–496. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northcutt RG, Brändle K. Development of branchiomeric and lateral line nerves in the axolotl. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;355:427–454. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahly I, Andermann P, Petit C. The zebrafish eya1 gene and its expression pattern during embryogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 1999;209:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s004270050270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Northcutt RG, Catania KC, Criley BB. Development of lateral line organs in the axolotl. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;340:480–514. doi: 10.1002/cne.903400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Northcutt RG, Brändle K, Fritzsch B. Electroreceptors and mechanosensory lateral line organs arise from single placodes in axolotls. Dev. Biol. 1995;168:358–373. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freitas R, Zhang G, Albert JS, Evans DH, Cohn MJ. Developmental origin of shark electrosensory organs. Evol. Dev. 2006;8:74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.05076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth A. Development of catfish lateral line organs: electroreceptors require innervation, although mechanoreceptors do not. Naturwissenschaften. 2003;90:251–255. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vischer HA. The development of lateral-line receptors in Eigenmannia (Teleostei, Gymnotiformes). II. The electroreceptive lateral-line system. Brain Behav. Evol. 1989;33:223–236. doi: 10.1159/000115930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nachtrieb HF. The primitive pores of Polyodon spathula (Walbaum) J. Exp. Zool. 1910;9:455–468. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jørgensen JM, Flock A, Wersäll J. The Lorenzinian ampullae of Polyodon spathula. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1972;130:362–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkens LA, Russell DF, Pei X, Gurgens C. The paddlefish rostrum functions as an electrosensory antenna in plankton feeding. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1997;264:1723–1729. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkens LA, Wettring B, Wagner E, Wojtenek W, Russell D. Prey detection in selective plankton feeding by the paddlefish: is the electric sense sufficient? J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:1381–1389. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.8.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grande L, Bemis WE. Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of fossil and recent paddlefishes (Polyodontidae) with comments on the interrelationships of Acipenseriformes. J. Vert. Paleontol. 1991;11(Suppl.):1–121. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grande L, Bemis WE. Interrelationships of Acipenseriformes, with comments on “Chondrostei”. In: Stiassny MLJ, Parenti LR, Johnson GD, editors. Interrelationships of Fishes. Academic Press; San Diego; 1996. pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bemis WE, Findeis E, Grande L. An overview of Acipenseriformes. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1997;48:25–71. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grande L, Jin F, Yabumoto Y, Bemis WE. †Protopsephurus liui, a well-preserved primitive paddlefish (Acipenseriformes: Polyodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous of China. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2002;22:209–237. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilton EJ, Grande L, Bemis WE. Skeletal anatomy of the shortnose sturgeon, Acipenser brevirostrum Lesueur, 1818, and the systematics of sturgeons (Acipenseriformes, Acipenseridae) Fieldiana: Life Earth Sci. 2011;3:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlosser G. Induction and specification of cranial placodes. Dev. Biol. 2006;294:303–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northcutt RG, Bemis WE. Cranial nerves of the coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae [Osteichthyes: Sarcopterygii: Actinistia], and comparisons with other craniata. Brain Behav. Evol. 1993;42:1–76. doi: 10.1159/000114175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishikawa S, Sasaki F. Internalization of styryl dye FM1-43 in the hair cells of lateral line organs in Xenopus larvae. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996;44:733–741. doi: 10.1177/44.7.8675994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heller S, Bell AM, Denis CS, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ. Parvalbumin 3 is an abundant Ca2+ buffer in hair cells. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2002;3:488–498. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-2050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Streit A. The preplacodal region: an ectodermal domain with multipotential progenitors that contribute to sense organs and cranial sensory ganglia. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2007;51:447–461. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072327as. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neill P, McCole RB, Baker CVH. A molecular analysis of neurogenic placode and cranial sensory ganglion development in the shark, Scyliorhinus canicula. Dev. Biol. 2007;304:156–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodznick D, Northcutt RG. Electroreception in lampreys: evidence that the earliest vertebrates were electroreceptive. Science. 1981;212:465–467. doi: 10.1126/science.7209544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronan MC, Bodznick D. End buds: non-ampullary electroreceptors in adult lampreys. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1986;158:9–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00614515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collazo A, Fraser SE, Mabee PM. A dual embryonic origin for vertebrate mechanoreceptors. Science. 1994;264:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.8153631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith SC. Pattern formation in the urodele mechanoreceptive lateral line: what features can be exploited for the study of development and evolution? Int J Dev Biol. 1996;40:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilmour DT, Maischein HM, Nusslein-Volhard C. Migration and function of a glial subtype in the vertebrate peripheral nervous system. Neuron. 2002;34:577–588. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bemis WE, Grande L. Early development of the actinopterygian head. I. External development and staging of the paddlefish Polyodon spathula. J. Morphol. 1992;213:47–83. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052130106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Filipski GT, Wilson MVH. Sudan Black B as a nerve stain for whole cleared fishes. Copeia. 1984;1984:204–208. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Modrell MS, Buckley D, Baker CVH. Molecular analysis of neurogenic placode development in a basal ray-finned fish. Genesis. 2011;49:278–294. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]