Abstract

Background:

Symptomatically ‘silent’ gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) may be underdiagnosed.

Objective:

To determine the prevalence of untreated GORD without heartburn and/or regurgitation in primary care.

Methods:

Patients were included if they had frequent upper gastrointestinal symptoms and had not taken a proton pump inhibitor in the previous 2 months (Diamond study: NCT00291746). GORD was diagnosed based on the presence of reflux oesophagitis, pathological oesophageal acid exposure, and/or a positive symptom–acid association probability. Patients completed the Reflux Disease Questionnaire (RDQ) and were interviewed by physicians using a prespecified symptom checklist.

Results:

GORD was diagnosed in 197 of 336 patients investigated. Heartburn and/or regurgitation were reported in 84.3% of patients with GORD during the physician interviews and in 93.4% of patients with GORD when using the RDQ. Of patients with heartburn and/or regurgitation not identified at physician interview, 58.1% (18/31) reported them at a ‘troublesome’ frequency and severity on the RDQ. Nine patients with GORD did not report heartburn or regurgitation either at interview or on the RDQ.

Conclusions:

Structured patient-completed questionnaires may help to identify patients with GORD not identified during physician interview. In a small proportion of consulting patients, heartburn and regurgitation may not be present in those with GORD.

Keywords: Bloating, oesophageal endoscopy, oesophageal pH monitoring, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, regurgitation, upper abdominal pain

Introduction

Heartburn and regurgitation are the key symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).1 The Montreal consensus guidelines recommend that, for epidemiological research purposes, a symptom-based diagnosis of GORD should be made when at least mild heartburn and/or regurgitation occur on 2 or more days per week or when moderate/severe heartburn and/or regurgitation occur on 1 or more days per week.1 For mainstream clinical practice, the guidelines define GORD as the presence of patient-reported ‘troublesome’ reflux-induced symptoms (symptoms that adversely affect well being).1 For research applications and as a reference standard, objective tests are used to determine the presence or absence of reflux disease, including oesophagoscopy and wireless pH recording together with symptom–association monitoring.2 Current recommendations for the treatment of GORD concentrate on managing symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation.3,4

It has been suggested that symptomatically ‘silent’ reflux disease may be common and underdiagnosed. Large population-based endoscopic and symptom surveys have shown that reflux oesophagitis can be present without heartburn or regurgitation or without any other upper gastrointestinal symptoms.5 Furthermore, a large study of patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma suggested that, in the period leading to diagnosis of the adenocarcinoma, a substantial proportion of individuals did not have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation.6 In South Korea, where upper endoscopy is performed as part of routine health checks, 44% of individuals with GORD had reflux oesophagitis in the absence of heartburn and regurgitation.7

Little information is available in Western populations about the prevalence of GORD without heartburn or regurgitation. Furthermore, previous studies were based solely on endoscopic findings and did not address the prevalence of pH-positive, non-erosive reflux disease without heartburn or regurgitation. The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of GORD without symptoms of heartburn and/or regurgitation in patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal symptoms, to assess the symptom profile in these patients, and to identify potential risk factors. By systematically performing pH-metry in all patients, we have evaluated individuals with GORD diagnosed not only by endoscopy but also with pH monitoring.

Methods

Study population

The Diamond study (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00291746) was conducted in north-western Europe (Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the UK) and in Canada.2 The study recruited patients aged 18–79 years who presented in primary care with frequent upper gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 336). Individuals were included if they had not taken a proton pump inhibitor in the past 2 months. Patients had to have experienced upper gastrointestinal symptoms of any severity on at least 2 days per week in the 4 weeks before the start of the study. Entry into the study also required that patients had experienced at least mild upper gastrointestinal symptoms on at least 3 days of the 7 days before study inclusion. Major exclusion criteria were: upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the year before the study; previous anti-reflux surgery, surgery for peptic ulcer or other gastrointestinal resection; daily use of acetylsalicylic acid (>165 mg/day) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (any dose); and ‘alarm’ features (e.g. dysphagia, anaemia, gastrointestinal blood loss, involuntary weight loss).

Study investigations

Patient symptoms were assessed both by a physician and by patient self-reporting. The protocol-driven symptom assessment by a physician included determination of the presence (graded by severity) or absence of 19 upper gastrointestinal symptoms, including heartburn and regurgitation.2 Owing to the differences in the referral procedures of the various healthcare systems, interviews were conducted by secondary care physicians in Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the UK and by primary care physicians in Canada.

All patients self-reported their symptoms at study entry by completing the Reflux Disease Questionnaire (RDQ). Investigators were blinded to the RDQ results. The RDQ is a 12-item, patient-reported outcome instrument that has been psychometrically validated for evaluative and diagnostic and purposes.2,8–10 The frequency and severity of symptoms fitting six descriptors covering heartburn, regurgitation, and dyspepsia are assessed individually using a 6-point Likert scale. Results from the RDQ were used to identify patients with heartburn and/or regurgitation. RDQ results were also used to identify patients meeting the Montreal symptom definition of GORD for research purposes of either mild heartburn and/or regurgitation occurring on at least 2 days per week or moderate/severe heartburn and/or regurgitation occurring on at least 1 day per week.1

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

All patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy no more than 10 days after completing the RDQ. Reflux oesophagitis and other endoscopic abnormalities were noted, and reflux oesophagitis was diagnosed and graded according to the Los Angeles (LA) classification.

Oesophageal pH monitoring

All patients underwent 48-h oesophageal pH-metry. Oesophageal acid exposure was measured for 24 h from midnight on the first day of pH capsule placement to standardize the time window for pH data analysis. The symptom association probability (SAP) for association of symptoms with acid reflux episodes was determined over 24 h from midnight on the day the pH capsule was placed.

Diagnostic criteria

GORD was defined a priori as the presence of at least one of the following three criteria: reflux oesophagitis on endoscopy (LA grades A–D); pathological distal oesophageal acid exposure (oesophageal pH <4 for >5.5% of the time over the 24-h period of analysis); and/or a positive (>95%) SAP for association of symptoms with episodes of acid reflux.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the different comparator groups, using percentages and mean values.

Results

GORD on investigation

In our study population, GORD was diagnosed in 197 (58.6%) of the 336 primary care patients investigated, based on the presence of one or more of the following: reflux oesophagitis; pathological distal oesophageal acid exposure; and a positive SAP. Demographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with GORD on investigation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on investigation: overall and without heartburn/regurgitation

| Characteristic | Total (n = 197) | No heartburn/regurgitation (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.8 ± 13.3 | 48.7 ± 14.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 112 (56.9) | 4 (44.4) |

| Female | 85 (43.1) | 5 (55.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 4.4 | 25.7 ± 4.4 |

| Helicobacter pylori positive | 46 (23.4) | 2 (22.2) |

| Hiatal hernia | 90 (45.7) | 2 (22.2) |

| Reflux oesophagitis | 118 (59.9) | 2 (22.2) |

| LA grade A | 61 (31.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| LA grade B | 49 (24.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| LA grade C | 6 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| LA grade D | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Barrett's oesophagus | 9 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Time with pH <4 for >5.5% of the time during 24 h | 137 (69.5) | 7 (77.8) |

| SAP >95% | 51 (25.9) | 0 (0.0) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

BMI, body mass index; LA, Los Angeles classification; SAP, symptom association probability.

Heartburn and/or regurgitation in patients with proven GORD on investigation

Figure 1 shows, for the 197 untreated patients diagnosed with GORD on investigation, the number of individuals with and without heartburn and/or regurgitation identified at physician interview and by independent patient self-reporting. During interview with a physician, 84.3% (166/197) of patients with proven GORD reported heartburn and/or regurgitation and 15.7% (31/197) did not report these symptoms. Independent self-reporting of symptoms using the RDQ revealed the presence of heartburn and/or regurgitation of any frequency or severity in 93.4% (184/197) of patients with proven GORD. Overall, typical symptoms of heartburn and/or regurgitation were captured by physician interview and/or the RDQ in 95.4% (188/197) of patients with proven GORD on investigation.

Figure 1.

Presence and absence of heartburn and/or regurgitation, identified by physician interview and patient self-reporting, in patients diagnosed with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on investigation.

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

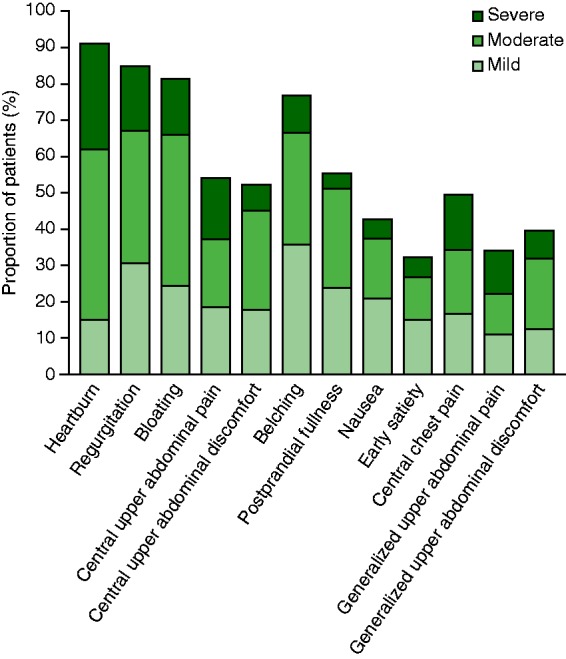

The mean number of upper gastrointestinal symptoms reported per patient with proven GORD identified at physician interview was 8.3. The presence and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms reported in these 166 patients are shown in Figure 2. Of patients with proven GORD not identified as having heartburn and/or regurgitation at physician interview, 71.0% (22/31) reported these symptoms on the RDQ and 58.1% (18/31) reported them at a frequency and severity meeting the Montreal symptom definition of GORD (i.e. they had ‘troublesome’ reflux symptoms).1

Figure 2.

Presence and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with heartburn and/or regurgitation reported at physician interview (n = 166).

GORD without heartburn or regurgitation

Of the 197 patients with proven GORD, nine (4.6%) did not report heartburn or regurgitation either at physician interview or on the RDQ (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics of the nine patients are shown in Table 1. In seven of these patients, GORD was diagnosed solely on the basis of pathological oesophageal acid exposure. All seven had oesophageal pH <4 for between 5.5% and 9.5% of the time over the 24-h period of analysis. The other two patients had reflux oesophagitis, despite normal pH monitoring results.

The mean number of upper gastrointestinal symptoms per patient reported at physician interview in those with proven GORD but without heartburn or regurgitation was 4.2. Figure 3 shows the presence and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms reported in the nine patients with proven GORD without heartburn or regurgitation at interview and on the RDQ. When the nine patients were asked to identify their most bothersome upper gastrointestinal symptom, this was bloating in three, central upper abdominal pain in three, and central upper abdominal discomfort, nausea, or central chest pain in one patient each. Two (22%) of the nine patients had a positive response to 2 weeks of proton pump inhibitor treatment with esomeprazole 40 mg daily (defined as absence of the most bothersome upper gastrointestinal symptom during the last 3 days of the treatment period).

Figure 3.

Presence and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease without heartburn or regurgitation (n = 9).

Discussion

In primary care, 15.7% of patients with untreated proven GORD did not report heartburn or regurgitation during an interview with a physician. However, the majority of these patients self-reported heartburn or regurgitation on a structured questionnaire (RDQ) at a level that was considered ‘troublesome’ according to the Montreal definition.1 Structured patient-completed questionnaires may thus identify some patients with GORD who have not been identified during physician interview.

A small proportion (4.6%) of patients with untreated proven GORD did not report heartburn or regurgitation at all. Instead, they reported bloating and central upper abdominal pain as their two most frequent symptoms. Heartburn and/or regurgitation may be very mild or absent in a minority of patients with GORD consulting in primary care, who present instead with troublesome, nonspecific, dyspepsia symptoms. At a time when empirical therapy is being recommended to save costs, our study shows that some patients will not be identified by any method of screening for heartburn and/or regurgitation. However, overall in the setting of primary care, the probability of having GORD is very low in patients who do not report symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation (when using a structured questionnaire). Previous studies have shown that physicians tend to underestimate the severity of reflux symptoms based on patient consultations.11 Our study expands on these findings, suggesting that the physician interview may fail to detect typical symptoms of GORD in some patients even when the symptom evaluation is formally structured by a clinical trial protocol, as was the case in the present study. These patients with GORD may be identified by use of structured questionnaires. There are many possible reasons why patients report symptoms on a questionnaire and not at a physician interview. The patient–doctor relationship, the time spent by the physician during the interview, and an understanding of what the terms ‘heartburn’ and ‘regurgitation’ mean could all play a role. In addition, many of the patients in the current analysis had a large number of symptoms and the reporting of other gastrointestinal symptoms may overshadow the reporting of typical GORD symptoms. Structured questionnaires that include a detailed description of each included symptom being screened for increase the probability of identifying heartburn and regurgitation,12 and this may have been the case with the RDQ used in this study, which contains a description of each symptom.

Seven of the nine patients with GORD but without heartburn and/or regurgitation had pathological oesophageal acid exposure by pH-metry and two had reflux oesophagitis. Such patients would not be identified as having GORD unless they underwent pH monitoring and/or endoscopy and would not be offered GORD treatment based on current guidelines, which are centred on managing symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation.3,4

Together, the RDQ and physician interviews captured typical symptoms of heartburn and/or regurgitation in 95% of the patients with proven GORD on investigation. In the small proportion of patients in whom these symptoms were not identified, dyspeptic symptoms predominated. Some patients with functional dyspepsia respond to acid-inhibitory therapy,13 and a proportion of these may have unrecognized reflux disease as the underlying cause of their symptoms. Our data suggest that GORD without heartburn and/or regurgitation is less common than may be suggested by data that rely solely on patient interview.

It is important to note that our data apply only to patients who are sufficiently troubled by upper abdominal and/or retrosternal symptoms to consult their primary care doctor. Given that the physician symptom assessment was structured by the study protocol, it is likely that the clinical interview in routine practice would be less sensitive in recognizing heartburn and regurgitation.

Our study indicates that the proportion of symptomatic patients with GORD who do not have any heartburn or regurgitation is small. Large-scale population endoscopic surveys suggest that this ‘truly silent’ GORD may be more prevalent among individuals who have no upper gastrointestinal symptoms at all.5 This category of individuals could pose a significant public health problem. They would likely never receive adequate therapy. Unrecognized long-term reflux may contribute to the development of complications of reflux disease and may account for the relatively large proportion of patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma who do not report typical symptoms of GORD.14 The reason for the absence of heartburn despite pathological acid exposure is unknown. Reduced oesophageal sensitivity to acid may play a role.15 Male sex, low body mass index, and old age have been implicated in some studies as potential risk factors for reflux oesophagitis without typical symptoms.16–18 The results of our study do not suggest that these are significant factors. Our descriptive statistics show, however, that there is a trend towards lower body mass index and older age in individuals with proven GORD who do not have typical reflux symptoms versus those who do.

The strengths of the Diamond study are its size, the unselected, consecutive inclusion of the population of patients presenting with frequent upper gastrointestinal symptoms in primary care, and the use of endoscopy and the latest techniques for wireless pH-monitoring. Our study has the interpretive limitations inherent to any post hoc data analysis, with the main predefined aims of the study having been to assess the accuracy of a symptom-based diagnosis of GORD.2

In conclusion, structured patient-completed questionnaires can be useful adjuncts to physician interviews in primary care and may identify more patients with GORD than physician interviews alone. However, a small proportion of patients with GORD diagnosed by endoscopy, pH-metry, and/or a positive SAP on investigation do not report any heartburn or regurgitation either at physician interview or on a self-completed questionnaire. Further research is necessary to determine the natural history of GORD in this group of patients and whether they are more likely to experience late complications of reflux disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Jenny Wissmar, from AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden, for her statistical support. Writing support was provided by Dr Anja Becher, from Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, and was funded by AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden. The current analysis was presented and selected as a poster of distinction at Digestive Disease Week, 18–21 May 2013, Orlando, FL, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden.

Conflict of interest

NV has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical and has ownership interest in Meridian Bioscience and Orexo. JD has received consultancy fees and research support from AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden. BW and LO were employees of AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden, at the time the study was conducted.

References

- 1.Vakil N, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) – a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1900–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut 2010; 59: 714–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tytgat GN, McColl K, Tack J, et al. New algorithm for the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1392–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dent J, Becher A, Sung J, et al. Systematic review: patterns of reflux-induced symptoms and esophageal endoscopic findings in large-scale surveys. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 863–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JY, Jung HK, Song EM, et al. Determinants of symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease: nonerosive reflux disease, symptomatic, and silent erosive reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25: 764–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw M, Dent J, Beebe T, et al. The Reflux Disease Questionnaire: a measure for assessment of treatment response in clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 31–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 52–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Armstrong D, Barkun A, et al. Symptom overlap in patients with upper gastrointestinal complaints in the Canadian confirmatory acid suppression test (CAST) study: further psychometric validation of the Reflux Disease Questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 1087–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McColl E, Junghard O, Wiklund I, et al. Assessing symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease: how well do clinicians' assessments agree with those of their patients? Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Flook N, Talley NJ, et al. One-week acid suppression trial in uninvestigated dyspepsia patients with epigastric pain or burning to predict response to 8 weeks' treatment with esomeprazole: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 26: 665–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fass R, Dickman R. Clinical consequences of silent gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2006; 8: 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bredenoord AJ. Mechanisms of reflux perception in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nozu T, Komiyama H. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol 2008; 43: 27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang FW, Tu MS, Chuang HY, et al. Erosive esophagitis in asymptomatic subjects: risk factors. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 1320–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho JH, Kim HM, Ko GJ, et al. Old age and male sex are associated with increased risk of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis: analysis of data from local health examinations by the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26: 1034–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]