Abstract

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, is a common benign dermatosis of pregnancy mainly affecting primigravidae and multiple pregnancies. We report here two cases of PEP with typical clinical and histological features presenting in the postpartum period.

Key words: pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, dermatosis

Introduction

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a common benign dermatosis of pregnancy mainly affecting primigravidae and multiple pregnancies. PEP usually evolves in the third trimester and resolves rapidly postpartum (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical features of two patients with postpartum polymorphic eruption of pregnancy.

| Patient | Maternal age | Primagravida | Delivery gestational age | Outcome | Onset | Duration of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy | Distribution | Morphology | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 21 | 12 days postpartum | Abdomen, thighs | Urticarial plaques | |||||

| B | 26 | yes | Caesarean Section ....... |

Healthy boy | 5 days postpartum | 3 weeks | Abdomen, thighs | Urticarial plaques | Topical steroids, antihistamines |

We describe two cases of PEP with typical clinical and histological features presenting in the postpartum period.

Only few cases of PEP developing postpartum have been described in the literature. However, a rash appearing in the mother shortly after delivery still can be a specific dermatosis of pregnancy.

Case Report #1

A 21-year-old woman was referred to our Department of Dermatology complaining of an intense pruritic rash starting 12 days postpartum. The eruption initially developed in and around the abdominal striae distensae with a periumbilical sparing (Figure 1). The urticarial plaques and erythematous papules spread to the buttocks, thighs and lower lumbar region. On the abdomen tiny vesicles were observed. No facial involvement or hand and foot lesions were observed. The patient was successfully treated with prednisolone 20 mg daily for five days combined with high potency topical corticosteroids tapered over four weeks. A punch biopsy showed slight dermal edema and a predominantly perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophilic granulocytes (Figure 2). There were no epidermal alterations, no blisters and no vasculitis. Direct immunfluorescens study was negative.

Figure 1.

Erythematous papules and urticarial plaques with periumbilical sparing and accentuation in striae in a 21-year old woman with polymorphic eruption of pregnancy.

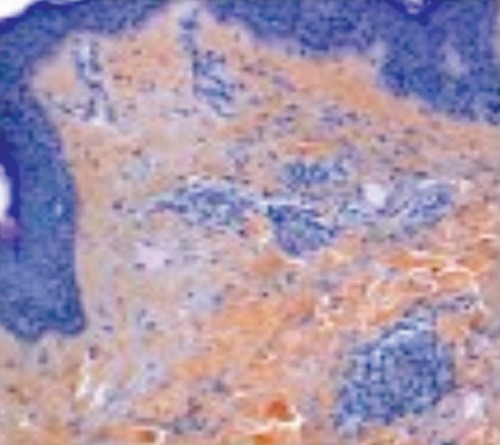

Figure 2.

Skin biopsy showing a predominantly perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophilic granulocytes. Typical, but not diagnostic for polymorphic eruption of pregnancy.

Case Report #2

A 26-year old primigravida woman was referred 5 days after giving birth with an itchy rash on the abdomen spreading to the proximal thighs. In the last week of her pregnancy, she had noticed some itchiness on her abdomen but no visible changes besides well-marked striae gravidarum. Objectively erythematous urticarial plaques and confluent papules were seen with a periumbilical sparing. High potency topical corticosteroids were initiated in combination with oral antihistamines and the itchy eruption subsided in the following 3 weeks. A 4 mm punch biopsy from the skin of the buttock showed a slight dermal edema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates with scattered perivascular and interstitial eosinophils. The patient was otherwise healthy apart from a tendency to depression treated with citalopram.

Discussion

In pregnancy, complex endocrinologic, immunologic, metabolic and vascular changes influence the skin in various ways. The multiple alterations of the skin during pregnancy can be classified as physiological skin changes, alterations in pre-existing skin diseases and specific dermatoses of pregnancy.1

The specific dermatoses of pregnancy represent a unique group of disease processes caused or exacerbated by the pregnancy state and include gestational pemphigoid (herpes gestationis), prurigo of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis and PEP/PUPPP.

PEP is a common distinct clinical entity with an estimated incidence in a single pregnancy of one in 130–300 pregnancies.2–4 It is generally considered as a benign dermatosis almost exclusive in primigravidae. The condition is more common in multiple pregnancies, where both earlier presentation and recurrence in second pregnancy are seen.5–7

The etiology is still unknown. It has been postulated that excessive abdominal distension and weight gain may act as a trigger for the skin changes due to connective tissue damage caused by overstretching.1,4 Rudolph et al. found a high frequency of atopy (55%) among their patients, especially in those with longer disease duration.

PEP usually evolves in the third trimester at the average gestational week of 35 and resolves rapidly postpartum and only exceptionally does it appear in the postpartum period.2,4 The lesions start in the abdominal striae in two thirds of the patients with a periumbilical sparing distinguishing PEP from other common rashes of pregnancy.8 The rash consists of very itchy small erythematous papules in the stretch marks which can coalesce to form larger urticarial abdominal plaques often surrounded by blanched halos. Occasionally eczematous, polycyclic and target lesions can be seen or vesicles (but never bullae) eventually in an acral dyshidrosiform pattern.4,5,6 Over days, the rash can spread over the thighs, buttocks, breasts, and arms with infrequent facial, hand and foot lesions.4 In spite of the severe pruritus, the absence of excoriations on the skin is a striking feature in contrast to excoriations related to cholestasis of pregnancy.

The condition is harmless to the mother but can be very annoying because of the severe itching.4,6 The average duration of healing is 4–6 weeks. There are no cutaneous manifestations in the newborn and the fetal prognosis is excellent.1 The diagnosis of PEP can be made clinically in typical cases based on the appearance of the rash. There are no specific laboratory abnormalities and only nonspecific histopathology with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some edema and eosinophils in the dermis.4 Direct immunofluorescence studies of the skin are by definition negative.4 Skin biopsies are only performed to rule out other differential diagnoses such as pemphigoid gestationis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, drug eruptions, viral eruptions and scabies. PEP is a self-limiting disor-der with resolution shortly after parturition and the treatment is symptomatic.4,6 General measures, such as mild to potent topical steroids can be helpful in treating symptoms from the disease together with systemic antihistamines. Furthermore application of emollients is basic in the treatment.4 In the most severe cases, as seen in one of the cases above, oral steroids may be necessary to control itching.4,5 If systemic corticosteroid treatment is necessary during pregnancy non-halogenated glucocorticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone) which are inactivated enzymatically in placenta should be administered as a short time therapy in a dosage of 0.5–2 mg/kg/day depending of the severity of symptoms.1

Conclusions

PEP is a frequently occurring pruritic, self-limited inflammatory dermatosis, most often seen in primiparous women and in the last trimester of pregnancy.1 If a rash develops after delivery, specific dermatoses of pregnancy still remains a possible diagnosis.

References

- 1.Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;9:748–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2006.06008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, et al. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestations. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger D, Vaillant L, Fignon A, et al. Specific pruritic diseases of pregnancy. A prospective study of 3192 pregnant women. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:734–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, et al. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy and multiple pregnancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:730–1. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen LM, Capeless EL, Krusinski PA, Maloney ME. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy and its relationship to maternal-fetal weight gain and twin pregnancy. Arch Dernatol. 1989;125:1534–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elling SV, McKenna P, Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in twin and triplet pregnancies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:378–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PUPPP) Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]