Abstract

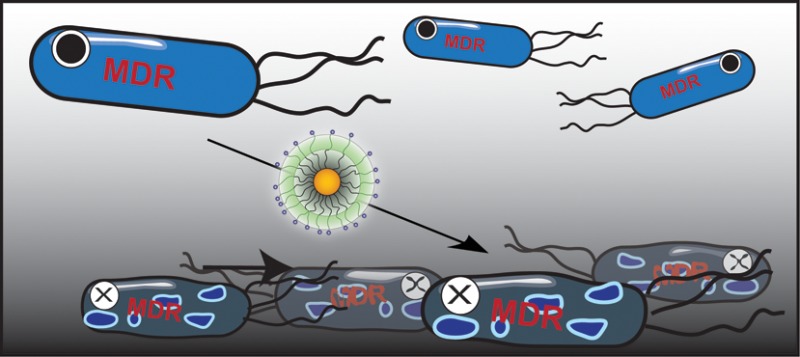

We present the use of functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to combat multi-drug-resistant pathogenic bacteria. Tuning of the functional groups on the nanoparticle surface provided gold nanoparticles that were effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive uropathogens, including multi-drug-resistant pathogens. These AuNPs exhibited low toxicity to mammalian cells, and bacterial resistance was not observed after 20 generations. A strong structure–activity relationship was observed as a function of AuNP functionality, providing guidance to activity prediction and rational design of effective antimicrobial nanoparticles.

Keywords: MDR E. coli, MRSA, uropathogens, antimicrobial agents, gold nanoparticles, structure−activity relationship, mode of action

The emergence of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacteria has become a severe threat to public health.1 According to a report published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, antibiotic resistant bacteria cause millions of infections and thousands of deaths every year in the U.S.2 Additionally, the significant and continuous decrease in the number of approved antibiotics in the past decade has contributed to the increasingly threatening situation3 that has resulted in an urgent need for the discovery of novel antibacterials and treatment strategies.4 There are a number of actively pursued strategies, including searching for new antimicrobials from natural products, modification of existing antibiotic classes, and the development of antimicrobial peptides.5

Nanoparticles (NPs) provide versatile platforms for therapeutic applications based on their physical properties.6−8 For example, NP size range is commensurate with biomolecular and bacterial cellular systems, providing additional interactions to small molecule antibiotics.9,10 The high surface to volume ratio allows incorporation of abundant functional ligands, enabling multivalency on NP surface to enhance interactions to target bacteria. Utilizing these characteristic features, NPs have been conjugated with known antibiotics to combat MDR bacteria. The antibiotic molecules can be infused with NPs via noncovalent interactions11,12 or incorporated on NPs via covalent bonds.13,14 Both methods have been reported for enhanced activity against bacteria, showing decreased minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) in comparison with use of free antibiotics.15−17 The improved performance is proposed to result from polyvalent effect of concentrated antibiotics on the NP surface as well as enhanced internalization of antibiotics by NPs.18 Yet the dependence on existing antibiotics in these approaches may not be able to delay the onset of acquired resistance.

The functional ligands on NP surface can provide direct multivalent interactions to biological molecules, allowing NPs to be exploited as self-therapeutic agents.19−21 This strategy can circumvent the employment and the potential limitation of existing antibiotics in nanocarrier systems.22 For assembly of such self-therapeutic NPs, the essentially inert and nontoxic nature of gold makes it an attractive core material.23 To this end, we synthesized a series of self-therapeutic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as an antimicrobial agent. The structure–activity relationship of the functional ligands on 2 nm core AuNP revealed that AuNP antimicrobial properties can be tailored through surface hydrophobicity, providing a new aspect to design antimicrobial nanomaterials. On the basis of these studies, we focused on the most potent AuNP candidate and tested this particle with clinically isolated uropathogens. The result showed inhibited growth of multiple strains of uropathogens, including many MDR strains and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Significantly, this AuNP did not induce bacterial resistance even after 20 generations. These particles are also compatible with mammalian cells: the maximum hemolytic index of this AuNP is >50, and at the MIC against MRSA, the C10-AuNP treated mammalian cells maintained >80% viability.

Results and Discussion

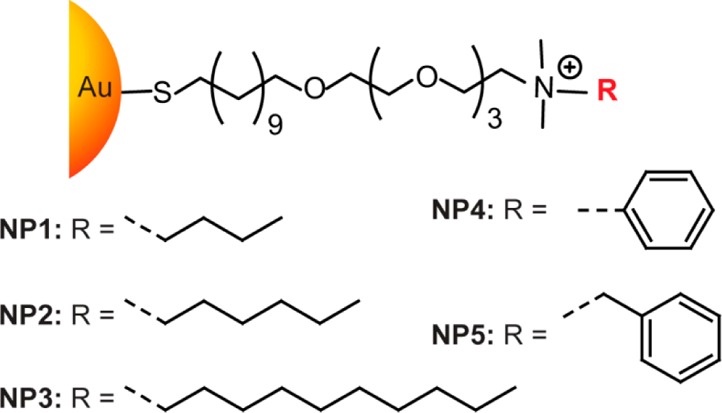

We recently reported that 2 nm core cationic monolayer-protected AuNPs can interact with cell membrane of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, resulting in formation of distinct aggregation patterns and lysis of bacterial cell.24 Similarly, Jiang and co-workers also demonstrated that blebbing caused by cationic AuNPs induced bacterial membrane damage.20 These results suggested that 2 nm AuNPs with cationic surface properties could be used as antimicrobial agents. To systematically investigate the role of surface chemistry in NP antimicrobial efficacy, AuNPs were synthesized with a range of different cationic functionalities featuring different chain length, nonaromatic, and aromatic characteristics (Figure 1). All AuNPs were highly soluble in water; including NP 3 with the most hydrophobic end group (stock solution concentration was 56 μM).

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of functional ligands on AuNPs.

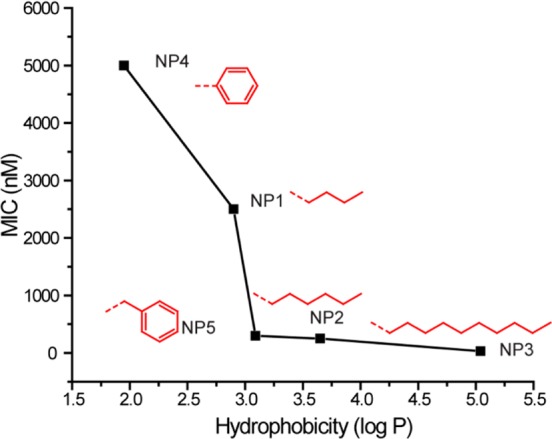

We first evaluated the functional AuNP antimicrobial activities on a laboratory strain (Escherichia coli DH5α), using broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs).25 AuNPs were incubated with 5 × 105 cfu/mL of E. coli overnight. All AuNPs were able to completely inhibit the proliferation of E. coli at nanomolar concentrations; the MICs of different AuNPs, however, varied by the R group. To correlate antimicrobial activity with AuNP surface functionality, we plotted the MICs against the calculated AuNP end group log P values that quantitatively represent the relative NP surface hydrophobicity (Figure 2).26 A marked structure–activity relationship was observed, with hydrophobic NPs being more effective against E. coli growth. The most hydrophobic AuNP tested, NP 3 that carried an n-decane end group was capable of inhibiting E. coli proliferation at only 32 nM.

Figure 2.

MIC values (nM) of AuNPs bearing different hydrophobic surface ligands against laboratory E. coli DH5α. Log P represents the calculated hydrophobic values of the end groups.

We next tested the antimicrobial activities of the most potent antimicrobial (NP 3) on uropathogenic E. coli clinical isolates (Table 1). Five isolates with differing resistance to clinically used antibiotics (resistant to 1–17 drugs, depending on strain) were used for this study. NP 3 suppressed the growth of all five uropathogenic strains of E. coli, including three MDR at a concentration of 16 nM, lower27 or similar to20 reported antibiotic-capped AuNPs. The comparable MIC values of MDR and laboratory strains suggest that C10-AuNP could potentially address the common mechanisms of bacterial resistance.

Table 1. MIC Values of NP 3 against Uropathogens.

| strain | species | MIC (nM) | no. of resistant drugs | MDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-2 | E. coli | 16 | 1 | No |

| CD-496 | E. coli | 16 | 2 | Yes |

| CD-3 | E. coli | 16 | 3 | Yes |

| CD-19 | E. coli | 16 | 4 | Yes |

| CD-549 | E. coli | 16 | 17 | Yes |

| CD-866 | E. cloacae complex | 16 | 2 | Yes |

| CD-1412 | E. cloacae complex | 8 | 4 | Yes |

| CD-1545 | E. cloacae complex | 16 | 7 | Yes |

| CD-1006 | P. aeruginosa | 16 | 1 | No |

| CD-23 | P. aeruginosa | 32 | 13 | Yes |

| CD-1578 | S. aureus | 64 | 4 | Yes |

| CD-489 | S. aureus - MRSA | 32 | 10 | Yes |

Next, NP 3 was further tested with more species/strains of uropathogenic clinical isolates, including Gram-negative Enterobacter cloacae complex and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Gram-positive S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (Table 1). Among these isolates, P. aeruginosa has intrinsic resistance to a variety of antibiotics due to their exceptionally low outer-membrane permeability and multidrug efflux pumps.28 Likewise, S. aureus has been a stumbling block for antimicrobial treatment, overcoming most of the therapeutic chemo-agents developed in the past five decades.29 Particularly, MRSA has emerged as “superbug”, resistant to most antibiotics commonly used for the staph infections.30 NP 3 was effective in treating each of these pathogens, with MICs of 8–64 nM.

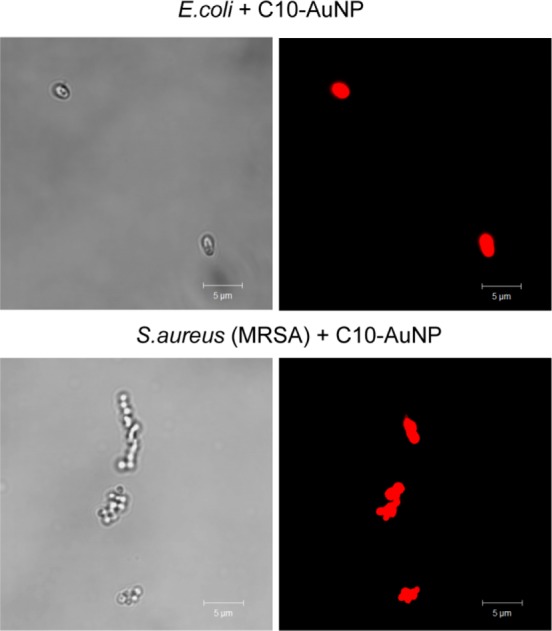

On the basis of the enhanced toxicity of NP 3, we hypothesized that the cationic hydrophobic AuNPs are particularly effective at compromising the integrity of bacterial membrane, causing toxicity to bacterial cells.24 To support this hypothesis, we employed a propidium iodide (PI) staining assay. PI can only penetrate bacterial cells with compromised membrane and binds nucleic acids, with a concomitant enhancement of red fluorescence.31,32 Uropathogens, E. coli CD-2 and S. aureus CD-489, were chosen as representative Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains. Bacteria (1 × 108 cfu/mL) were incubated with NP 3 at a final concentration of 500 nM for 3 h at 37 °C and then stained with PI before imaging. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images in Figure 3 showed NP-induced membrane damage in both bacteria.

Figure 3.

PI staining showing NP 3 (C10-AuNP)-induced bacterial cell membrane damage. Scale bar is 5 μm.

To study the development of bacterial resistance to NP 3, E. coli CD-2 was exposed to sub-MIC (66% of MIC) of NP 3, with the obtained bacterial cell population defined as the first generation. After harvesting the first generation, the MIC was tested and a second generation was generated by exposing the first generation at its sub-MIC (66%). After 20 generations, E. coli remained susceptible to the original MIC of 16 nM. Compared to literature reported rate at which E. coli acquires resistance to conventional antibiotics,20 NP 3 significantly delayed evolution of resistance. This lack of bacterial adaptation provides a means of potentially controlling and preventing the drug resistance.33,34

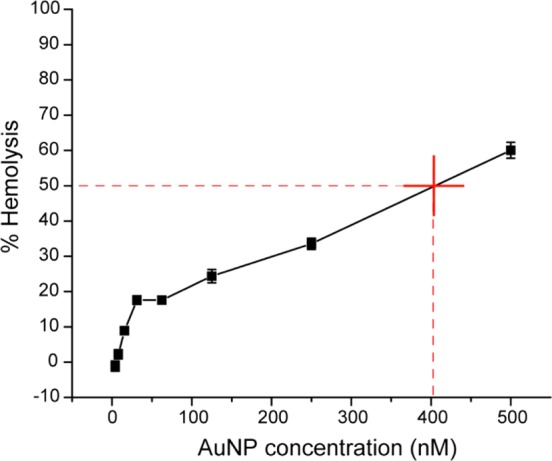

To assess the biocompatibility of our antimicrobial NP 3, we performed hemolysis assay on human red blood cells as well as viability assays on mammalian cells. At all the MIC concentrations tested (in the range of 4 nM to 128 nM), NP 3 showed modest hemolytic activity as shown in Figure 4. HC50, which is the concentration to lyse 50% of human red blood cells,35 was ∼400 nM for NP 3. The hemolytic index (HC50/MIC) was used to assess NP 3 selectivity against eukaryotic cells; therefore, the maximum hemolytic index of NP 3 was 50 (400 nM/8 nM). Similarly, after treatment with NP 3 at 128 nM, NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells maintained a viability of 80% (see Supporting Information), indicating low toxicity against mammalian cells. The observed AuNP cell selectivity could be explained by the fact that the surface of bacterial cells are more negatively charged than mammalian cells,36 therefore accounting for the better affinity toward multications in bacteria. Also, the presence of cholesterol in mammalian cell membranes helps to stabilize the membranes, making them less sensitive to destruction by antimicrobial AuNPs.37 It should be noted that the mammalian cell culture model used in this study may not fully reflect the in vivo toxicity profile.

Figure 4.

Hemolytic activity of NP 3 at different concentrations. HC50 was estimated to be ∼400 nM (as denoted by the red cross in figure).

Conclusion

We report here an antimicrobial strategy using self-therapeutic AuNPs to combat MDR bacteria. Cationic and hydrophobic functionalized AuNPs effectively suppressed growth of 11 clinical MDR isolates, including both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The NP ligand structure–activity relationship revealed that surface chemistry played an important role in AuNP antimicrobial properties, providing a design element for prediction and rational design of new antibiotic NPs. Considering the efficient antimicrobial effect on MDR bacteria, the high biocompatibility, and the slow development of resistance, cationic hydrophobic nanoparticles such as NP 3 offer a promising strategy for the long-term combating of (MDR) bacteria, a key issue in healthcare.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All the reagents/materials required for nanoparticle synthesis were purchased from Fisher Scientific, except for gold salt, which was obtained from Strem Chemicals, Inc. The organic solvents were from Pharmco-Aaper or Fisher Scientific and used as received except for dichloromethane that was distilled in the presence of calcium hydride. NIH-3T3 cells (ATCC CRL-1658) were purchased from ATCC. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (DMEM; ATCC 30-2002) and fetal bovine serum (Fisher Scientific, SH3007103) were used in cell culture.

NP Synthesis

Cationic gold nanoparticles were synthesized and characterized as previously reported.38,39 (See Supporting Information for synthesis and characterization.)

Determination of Antimicrobial Activities of Cationic Gold Nanoparticles

Bacteria were cultured in LB medium at 37 °C and 275 rpm until stationary phase. The cultures were then harvested by centrifugation and washed with 0.85% sodium chloride solution for three times. Concentrations of resuspended bacterial solution were determined by optical density measured at 600 nm. M9 medium was used to make dilutions of bacterial solution to a concentration of 1 × 106 cfu/mL. A volume of 50 μL of these solutions was added into a 96-well plate and mixed with 50 μL of NP solutions in M9, giving a final bacterial concentration of 5 × 105 cfu/mL. NPs concentration varied in half fold according to a standard protocol, ranging from 125 to 3.9 nM. A growth control group without NPs and a sterile control group with only growth medium were carried out at the same time. Cultures were performed in triplicates, and at least two independent experiments were repeated on different days. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of AuNP that inhibits visible growth as observed with the unaided eye.25

Propidium Iodide Staining Assay

E. coli CD-2 and MRSA CD-489 (1 × 108 cfu/mL) were incubated with 500 nM C10-AuNP in M9 at 37 37 °C and 275 rpm for 3 h. The bacteria solutions were then mixed with PI (2 μM) and incubated for 30 min in dark. Five microliters of the samples was placed on a glass slide with a glass coverslip and observed with a confocal laser scanning microscopy, Zeiss 510 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a 543 nm excitation wavelength.

Resistance Development

E. coli CD-2 was inoculated in M9 medium with 10.4 nM (2/3 of 15.6 nM, MIC) at at 37 °C and 275 rpm for 16 h. The culture was then harvested and tested for MIC as describe above. E. coli CD-2 was cultured without NP as well every time as a control for comparison of MICs.

Hemolysis Assay

Hemolysis assay was performed on human red blood cells as we described in a previous study.40 Briefly, citrate-stabilized human whole blood (pooled, mixed gender) was purchased from Bioreclamation LLC, Westbury, NY. The red blood cells were purified and resuspended in 10 mL of phosphate buffered saline as soon as received. A total of 0.1 mL of RBC solution was added to 0.4 mL of NP solution in PBS in 1.5 mL centrifuge tube.

The mixture was incubated at 37 °C, 150 rpm for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance value of the supernatant was measured at 570 nm with absorbance at 655 nm as a reference. RBCs incubated with PBS as well as water were used as negative and positive control, respectively. All samples were prepared in triplicate. The percent hemolysis was calculated using the following formula:

Mammalian Cell Viability Assay

A total of 20 000 NIH 3T3 (ATCC CRL-1658) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; ATCC 30-2002) with 10% bovine calf serum and 1% antibiotics at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 48 h. Old media was removed and cells were washed one time with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before addition of NPs in the prewarmed 10% serum containing media. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell viability was determined using Alamar blue assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen Biosource). After a wash step with PBS three times, cells were treated with 220 μL of 10% alamar blue in serum containing media and incubated at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 3 h. After incubation, 200 μL of solution from each wells was transferred in a 96-well black microplate. Red fluorescence, resulting from the reduction of Alamar blue solution, was quantified (excitation/emission: 560 nm/590 nm) on a SpectroMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Device) to determine the cellular viability. Cells without any NPs were considered as 100% viable. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (EB014277-01). Clinical samples were kindly provided to Dr. Margaret Riley by the Cooley Dickinson Hospital Microbiology Laboratory (Northampton, MA).

Supporting Information Available

Nanoparticle synthesis; 3T3 mammalian cell viability after incubation with NP 3; PI staining showing NP-induced bacterial cell membrane damage; uropathogenic strain information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Neu H. C. The Crisis in Antibiotic-Resistance. Science 1992, 257, 1064–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FY15 Detect and Protect Against Antibiotic Resistance Budget Initiative; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, 2003, http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/FY15-DPAR-budget-init.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B.; Powers J. H.; Brass E. P.; Miller L. G.; Edwards J. E. Trends in Antimicrobial Drug Development: Implications for the Tuture. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanis A. J. Resistance to Antibiotics: Are We in the Post-Antibiotic Era?. Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell K. M. G.; Hodgkinson J. T.; Sore H. F.; Welch M.; Salmond G. P. C.; Spring D. R. Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: Current Strategies for the Discovery of Novel Antibacterials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10706–10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. E.; Chen Z.; Shin D. M. Nanoparticle Therapeutics: An Emerging Treatment Modality for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer D.; Karp J. M.; Hong S.; FaroKhzad O. C.; Margalit R.; Langer R. Nanocarriers as an Emerging Platform for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De M.; Ghosh P. S.; Rotello V. M. Applications of Nanoparticles in Biology. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4225–4241. [Google Scholar]

- Redl F. X.; Black C. T.; Papaefthymiou G. C.; Sandstrom R. L.; Yin M.; Zeng H.; Murray C. B.; O’Brien S. P. Magnetic, Electronic, and Structural Characterization of Nonstoichiometric Iron Oxides at the Nanoscale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14583–14599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M. C.; Astruc D. Gold Nanoparticles: Assembly, Supramolecular Chemistry, Quantum-Size-Related Properties, and Applications toward Biology, Catalysis, and Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 293–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace A. N.; Pandian K. Antibacterial Efficacy of Aminoglycosidic Antibiotics Protected Gold Nanoparticles—A Brief Study. Colloids Surf., A 2007, 297, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ahangari A.; Salouti M.; Heidari Z.; Kazemizadeh A. R.; Safari A. A. Development of Gentamicin-Gold Nanospheres for Antimicrobial Drug Delivery to Staphylococcal Infected Foci. Drug Delivery 2013, 20, 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H. W.; Ho P. L.; Tong E.; Wang L.; Xu B. Presenting Vancomycin on Nanoparticles To Enhance Antimicrobial Activities. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Rai A.; Prabhune A.; Perry C. C. Antibiotic Mediated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles with Potent Antimicrobial Activity and Their Application in Antimicrobial Coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 6789–6798. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. N.; Smith K.; Samuels T. A.; Lu J. R.; Obare S. O.; Scott M. E. Nanoparticles Functionalized with Ampicillin Destroy Multiple-Antibiotic-Resistant Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter aerogenes and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2768–2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz A. M.; Girilal M.; Mandy S. A.; Somsundar S. S.; Venkatesan R.; Kalaichelvan P. T. Vancomycin Bound Biogenic Gold Nanoparticles: A Different Perspective for Development of Anti VRSA Agents. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 636–641. [Google Scholar]

- Alekshun M. N.; Levy S. B. Molecular Mechanisms of Antibacterial Multidrug Resistance. Cell 2007, 128, 1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Y.; Jiang X. Y. Multiple Strategies to Activate Gold Nanoparticles as Antibiotics. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 8340–8350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvizo R. R.; Saha S.; Wang E. F.; Robertson J. D.; Bhattacharya R.; Mukherjee P. Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Metastasis by a Self-Therapeutic Nanoparticle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 6700–6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Y.; Tian Y.; Cui Y.; Liu W. W.; Ma W. S.; Jiang X. Y. Small Molecule-Capped Gold Nanoparticles as Potent Antibacterial Agents That Target Gram-Negative Bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12349–12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresee J.; Maier K. E.; Boncella A. E.; Melander C.; Feldheim D. L. Growth Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by Mixed Monolayer Gold Nanoparticles. Small 2011, 7, 2027–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeletti L. B.; de Oliveira L. F.; Gonçalves K. d. A.; de Oliveira J. F. A.; Saito Â.; Kobarg J.; Santos J. H. Z. d.; Cardoso M. B. Tailored Silica–Antibiotic Nanoparticles: Overcoming Bacterial Resistance with Low Cytotoxicity. Langmuir 2014, 30, 7456–7464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor E. E.; Mwamuka J.; Gole A.; Murphy C. J.; Wyatt M. D. Gold Nanoparticles Are Taken up by Human Cells but Do Not Cause Acute Cytotoxicity. Small 2005, 1, 325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden S. C.; Zhao G. X.; Saha K.; Phillips R. L.; Li X. N.; Miranda O. R.; Rotello V. M.; El-Sayed M. A.; Schmidt-Krey I.; Bunz U. H. F. Aggregation and Interaction of Cationic Nanoparticles on Bacterial Surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6920–6923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand I.; Hilpert K.; Hancock R. E. W. Agar and Broth Dilution Methods To Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antimicrobial Substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano D. F.; Goldsmith M.; Solfiell D. J.; Landesman-Milo D.; Miranda O. R.; Peer D.; Rotello V. M. Nanoparticle Hydrophobicity Dictates Immune Response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3965–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresee J.; Maier K. E.; Melander C.; Feldheim D. L. Identification of Antibiotics Using Small Molecule Variable Ligand Display on Gold Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7516–7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. Multidrug Efflux Pumps of Gram-Negative Bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 5853–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K.; Cui L.; Kuroda M.; Ito T. The Emergence and Evolution of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends. Microbiol. 2001, 9, 486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens R. M.; Morrison M. A.; Nadle J.; Petit S.; Gershman K.; Ray S.; Harrison L. H.; Lynfield R.; Dumyati G.; Townes J. M.; et al. Invasive Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in the United States. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulos L.; Prevost M.; Barbeau B.; Coallier J.; Desjardins R. LIVE/DEAD BacLight: Application of A New Rapid Staining Method for Direct Enumeration of Viable and Total Bacteria in Drinking Water. J. Microbiol. Methods 1999, 37, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S. D.; Mann C. M.; Markham J. L.; Bell H. C.; Gustafson J. E.; Warmington J. R.; Wyllie S. G. The Mode of Antimicrobial Action of the Essential Oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree Oil). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B.; Marshall B. Antibacterial Resistance Worldwide: Causes, Challenges and Responses. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S122–S129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J.; Davies D. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren T.; Som A.; Rennie J. R.; Nelson C. F.; Urgina Y.; Nusslein K.; Coughlin E. B.; Tew G. N. Antibacterial and Hemolytic Activities of Quaternary Pyridinium Functionalized Polynorbornenes. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2008, 209, 516–524. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K. Control of Cell Selectivity of Antimicrobial Peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 1687–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K.; Sugishita K.; Fujii N.; Miyajima K. Molecular-Basis for Membrane Selectivity of an Antimicrobial Peptide, Magainin-2. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 3423–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust M.; Walker M.; Bethell D.; Schiffrin D. J.; Whyman R. Synthesis of Thiol-derivatised Gold Nanoparticles in a Two-[hase Liquid-Liquid System. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994, 7, 801–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler M. J.; Templeton A. C.; Murray R. W. Dynamics of Place-Exchange Reactions on Monolayer-Protected Gold Cluster Molecules. Langmuir 1999, 15, 3782–3789. [Google Scholar]

- Saha K; Moyano D. F.; Rotello V. M. Protein Coronas Suppress the Hemolytic Activity of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Nanoparticles. Mater. Horiz. 2014, 1, 102–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.