Abstract

Numerous studies show that individuals with substance use and gambling problems discount delayed and probabilistic outcomes at different rates than controls. Few studies, however, investigated the association of discounting with antisocial personality disorders (ASPD), and none evaluated whether sex impacts these relationships. Because females with ASPD exhibit different patterns of antisocial behavior than their male counterparts, they may also differ in their decision-making tendencies. This study examined the effects of ASPD and sex on discounting in pathological gamblers. Results revealed effects of ASPD, and an interaction between ASPD and sex, on probability discounting rates. None of these variables, however, were related to delay discounting. Females with ASPD highly preferred probabilistic outcomes, suggesting that female gamblers with ASPD are particularly impulsive when it comes to probabilistic rewards. Greater understanding of sex differences in ASPD might help guide the selection of more effective sex-specific prevention and treatment programs.

Keywords: Probability discounting, delay discounting, sex, gambling, antisocial personality disorder

Delay discounting is the behavioral process by which the subjective value of an outcome is reduced as a function of time. Delay discounting is viewed as an impulsivity measure reflecting how decision-making is impacted by immediacy. High delay discounting (i.e., steep discounting rates) indicates quick subjective devaluation of an outcome as a function of time, and thus reflects smaller controlling effect of a delayed outcome on the behavior of an individual. This concept might help explain irrational impulsive decisions such as when individuals repeatedly choose smaller immediate outcomes over larger more delayed outcomes. For instance, pathological gamblers might devalue outcomes associated with gambling abstinence (e.g., having more money and better family relationships), because these outcomes are usually delayed, whereas outcomes associated with gambling activities (e.g., chances of winning, thrill) are more immediately available.

An extensive body of literature has demonstrated that individuals with substance use disorders and pathological gambling discount delayed outcomes more steeply (i.e., they are more impulsive) than those without these addictive problems (see Bickel & Marsch, 2001; MacKillop et al., 2011; and Reynolds, 2006, for reviews). Further, individuals presenting with comorbid substance use and gambling problems discount more steeply than those presenting with a single disorder (Andrade & Petry, 2012; Petry, 2001; Petry & Casarella, 1999).

Another behavioral process that is theoretically linked to substance use disorders, and pathological gambling in particular, is probability discounting. Probability discounting refers to the process by which the subjective value of an outcome decreases as a function of the odds against receiving it. Low probability discounting (i.e., shallow discounting rates) indicates greater subjective value for probabilistic outcomes. Theoretically, it is a behavioral index reflecting another dimension of impulsivity—the tendency to take risks. Compared to delay discounting, probability discounting has been less systematically investigated, and the findings are less robust. Some data suggest that individuals with substance abuse or gambling problems discount probabilistic events at different rates than non-substance abuse non-gambling controls (Holt, Green, & Myerson, 2003; Madden, Petry, & Johnson, 2009; Reynolds, Richards, Horn, & Karraker, 2004), but these findings have not been consistently observed (Mitchell, 1999; Ohmura, Takahashi, & Kitamura, 2005; Shead, Callan, & Hodgins, 2008).

A psychiatric condition that is highly prevalent in individuals with substance use disorders and pathological gambling, and also linked to impulsive behaviors, is antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) (APA, 2000). Petry (2002) reported that substance abusers with ASPD discount delayed rewards significantly more steeply than substance abusers without ASPD, who in turn discount more steeply than non-ASPD non-substance abusing controls. However, these results were not replicated in two recent studies. Sargeant et al. (2012) compared delay discounting rates among substance abuse inpatients with and without ASPD and found no differences between the groups. Likewise, Swann et al. (2009) found no differences in impulsive choices in males on probation based on ASPD status. These discrepancies may be due to methodological differences across studies. All used different tasks to measure impulsive choices and involved widely diverging ranges of reinforcement amounts and delay intervals. Swann et al. (2009), for example, had participants choose between receiving 5 cents after a 5-sec delay and 15 cents after a 15-sec delay. In Petry (2002), participants made a series of hypothetical choices on which reward delays and amounts ranged from 6 hours to 25 years, and from $100 to $1000 dollars. Sargeant et al. (2012) also had participants make hypothetical choices, but relative to Petry (2002), reward amounts were smaller ($11-$85) and delays were shorter (7 to 186 days). Thus, the association between ASPD and delay discounting is not well understood, and no study has evaluated the relationship between ASPD and probability discounting. In theory, persons with ASPD should be impulsive with respect to probabilistic decisions as defining features of ASPD include reckless disregard for safety of self or others, and failure to plan ahead and conform to social norms.

Antisocial personality disorder, pathological gambling, and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The prevalence rates of these conditions, however, are substantially higher in males than females (Kessler et al., 2008; Petry et al., 2005; APA, 2000), and sex differences are particularly pronounced with respect to ASPD, for which the ratio of cases for men to women is 3:1 (APA, 2000). As a result, most research on this condition has focused on males, and relatively little is known about ASPD in females (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). Some studies indicate the existence of sex differences with respect to psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in persons with ASPD (see Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002 for a review). For example, ASPD is a risk factor for substance use disorders (e.g., Hesselbrock, Meyer, & Keener, 1985), but females with ASPD are even more vulnerable to developing substance use disorders than males with ASPD (Grant et al., 2004; Lewis, & Bucholz, 1991).

Among samples of substance abusers with ASPD, males are more likely to engage in aggressive behaviours, such as setting fires, initiating fights, and being cruel to animals, whereas females are more likely to run away without returning home, to lack remorse, to be impulsive, and to behave irresponsibly as parents (Cottler, Price, Compton, & Magers, 1995; Goldstein et al 1996, Mikulitch-Giverston et al., 2007). Among patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders, higher prevalence rates of lifetime anxiety, mood, and other personality disorders were found among females with ASPD compared to their male counterparts (Goldstein, et al., 2007). Further, females with ASPD report experiencing greater rates of lifetime adverse events, such as growing up with a parent with substance use problems, and they present with overall greater disability than males with ASPD (Alegria et al., 2013). Taken together, these data suggest that sex differences exist in terms of ASPD phenomenology and severity.

Regarding sex differences in terms of discounting, some studies have found no relationship between sex and discounting (e.g., de Wit et al., 2007), but others have shown that males discount delayed outcomes more steeply than females (e.g., Kirby & Marakovic, 1996; Petry, Kirby, & Kranzler, 2002). Because females with ASPD exhibit different patterns of antisocial behaviour and psychiatric comorbidity than their male counterparts, they may differ in their decision-making tendencies regarding delayed and probabilistic outcomes.

To summarize, the association between ASPD, addictive behaviors, and discounting is not well delineated, and the influence of sex on these relationships have not been evaluated. The present study was designed to examine the main and interactive effects of ASPD and sex on delay and probability discounting. The sample was comprised of individuals with pathological gambling, a psychiatric condition that is highly comorbid with ASPD.

Method

Participants

This study analyzed data from 226 treatment-seekers participating in a randomized clinical trial investigating treatments for pathological gambling (Petry, et al., 2006). Individuals were included in the study if they met the criteria for pathological gambling according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; APA, 2000), gambled during the preceding 2 months, were at least 18 years of age, and achieved a 5th grade reading level. Participants were excluded if they were receiving treatment for pathological gambling, expressed suicidal intent, or reported experiencing psychotic symptoms within the preceding month. Eligible participants provided informed consent approved by the University of Connecticut Health Center Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Participants completed a three hour interview, during which baseline data were collected concerning demographics, gambling severity, psychiatric history, and discounting. Participants were compensated $15 for the interview.

Assessment Instruments

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Grant, Steinberg, Kim, Rounsaville, & Potenza, 2004) evaluated pathological gambling and ASPD. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) evaluated the severity of gambling problems. The SOGS is a reliable and valid (Lesieur & Bloom, 1987; Stinchfield, 2002) 20-item instrument, with scores exceeding 4 indicating pathological gambling.

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1985) assessed problems within seven domains of functioning: medical, employment, alcohol, drug, legal, family, and psychiatric. An additional subscale evaluating gambling behaviour (ASI-G) was included in the assessment. Scores on ASI subscales range from 0 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating greater degrees of problem severity during the previous 30 days. Studies demonstrate that both the ASI and ASI-G have adequate psychometric properties (Leonhard et al., 2000; Lesieur & Blume, 1991, 1992; McLellan et al., 1985; Petry 2003, 2007). The Timeline Follow-Back method (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) assessed frequency and intensity of gambling behaviour during the preceding month. The assessment is valid and reliable (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000; Petry, 2003; Weinstock, Whelan, & Meyers, 2004), and involves the use of calendar prompts to elicit recent past gambling behaviors.

Probability discounting questionnaire

Probability discounting was assessed using a questionnaire (Madden et al., 2009) containing hypothetical choices between a smaller certain monetary amount and a larger probabilistic alternative. For instance, participants were asked “Would you prefer $20 for sure, or a 2-in-4 (50%) chance of winning $80?” The questionnaire was divided into three sections, each comprised of 10 questions. Within each section, the monetary values of the smaller and larger options were fixed, but the probabilities of obtaining the latter option varied. Specifically, the values were $20 versus $80 in section 1, $40 versus $100 in section 2, and $40 versus $60 in section 3. The probabilities associated with the larger option ranged from .10 to .83, .18 to .91, and .40 to .97 across the three sections, respectively. The reader is referred to Madden et al. (2009) for the full list of items and additional details describing the probability discounting estimation procedure.

Probability discounting procedure

Equation 1 was used to characterize probability discounting (Rachlin, Rainery, & Cross, 1991).

| (1) |

In this equation, V represents the discounted value of a reward. The amount of the reward is represented by A, the odds against winning the reward (i.e., 1 − p/p) is represented as θ, and h is a free parameter determining the probability discount rate.

This equation was used to estimate participants’ probability discount rate (h in the model) based on their indifference point in the questionnaire, that is, the point at which the subjective values of both choice options are equal. To estimate the discount rate yielding indifference, the parameter values of each pair of choice alternatives were substituted for the terms in this equation and used to solve for h. This procedure leads to indifference h values associated with each pair of choice alternatives, which are used to define the range of values from which participant’s discount rate is estimated.

To illustrate, consider the following two questions from the questionnaire:

Would you prefer $20 for sure, or a 1-in-5 chance (20%) of winning $80?

Would you prefer $20 for sure, or a 1-in-4 (25%) chance of winning $80?

The h-values at indifference associated with these two pairs of choices are.0.75 and 1.0, respectively. Therefore, if a participant chooses the smaller certain option for the first question, but then switches to the larger option for the second question, we assume that his/her indifference point lies between these two h values. We therefore use the geometric mean of these values (in this case, 0.866) as an estimate of the participant’s discount rate. When participants’ choices indicated more than one h-value, the discount parameter most consistent with their responses was selected based on the proportion of responses supporting each value. Participants who selected either the certain or the probabilistic outcome exclusively were respectively assigned the lowest (h = 0.33) or highest (h = 16.17) possible h-values on the questionnaire.

Delay discounting questionnaire

Delay discounting was assessed with the questionnaire developed by Kirby and colleagues (Kirby & Marakovic, 1996; Kirby et al., 1999), which is comprised of 27 questions divided into three sections. Each question contained a hypothetical choice involving a smaller monetary amount available immediately (S) and a larger one delayed by x number of days (L). The delay interval between S and L ranged from 7 to 186 days and the hypothetical reward amounts varied between $11 and $85. Each section of the questionnaire offered a different range of values for the L option, specifically, $25–$35, $50–$60, and $75–$85.

Delay discounting procedure

Equation 2 characterized delay discounting using the method described by Mazur (1984):

| (2) |

Here, the delay discount parameter is represented by the constant k, which determines how sharply the subjective value of A declines as a function of delay D. This equation was used to estimate each participant’s delay discount rate (k) based on their responses on the questionnaire, following the procedure outlined by Kirby and Marakovic (1996) as well as Kirby, Petry, and Bickel (1999). Similar to the probability discounting estimation procedure described above, the point at which participants switched from one alternative to the other provided the range of values within which their k-values were estimated. The discount parameter that was most consistent with their preferences throughout the questionnaire was then selected following the same method described for probability discounting. Participants who selected the S or L payoff exclusively were respectively assigned the highest (k = .25) and lowest (k = .0016) possible values of k on the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Baseline characteristics among male and female pathological gamblers with and without ASPD were compared using chi-square tests for discrete variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Variables that were not normally distributed (income, money spent on gambling in the past month, and probability (h), and delayed (k) discounting rates) were log transformed prior to analyses. When ANOVAs revealed significant differences among groups, least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc tests were used to analyze differences between each group with respect to the others.

Two Univariate Analysis of Variance tests (UNIANOVA) examined the association between ASPD status with rates of probability and delay discounting. Non-overlapping baseline variables that differed based on ASPD status were included as covariates in the model: education, age, and ASI gambling and drug scores. Analyses were adjusted for unequal group sizes using a conservative approach described by Overall and Spiegel (1969). Analyses were conducted using SPSS, and p values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of pathological gamblers by ASPD status and sex are presented in Table 1. The following four groups were formed: males without ASPD (n = 101), females without ASPD (n = 89), males with ASPD (n = 26), and females with ASPD (n = 10). These groups differed with regards to employment, marital status, age, years of education, number of endorsed DSM criteria for pathological gambling, days gambled past month, and ASI medical, drug, legal, and gambling scores. Regardless of ASPD status, females were less likely to be employed compared to men. Males and females with ASPD were less likely to be married than those without ASPD. Post hoc tests revealed that females without ASPD were older than the gamblers from the other groups. Females with ASPD had fewer years of education than both sexes without ASPD, but no difference was found relative to males with ASPD. Both males and females with ASPD endorsed more DSM gambling criteria than both groups without ASPD.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Pathological Gamblers by Antisocial Personality Disorder Status and Sex

| No Antisocial Personality Disorder | Antisocial Personality Disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | Statistic (df) | p | ||||

| Male (101) | Female (89) | Male (26) | Female (10) | |||

| Employed full time, % (n) | 66.3 (67) | 46.1 (41) | 57.7 (15) | 40.0 (4) | χ2(3) = 9.02 | .03 |

| Married/living together, % (n) | 46.5 (47) | 41.6 (37) | 15.4 (4) | 30.0 (3) | χ2(3) = 8.84 | .03 |

| Race, % (n) | χ2(6) = 11.95 | .06 | ||||

| Caucasian | 82.2 (83) | 91.0 (81) | 80.8 (21) | 60.0 (6) | ||

| African American | 9.9 (10) | 5.6 (5) | 11.5 (3) | 10.0 (1) | ||

| Other | 7.9 (8) | 3.4 (3) | 7.7 (2) | 30.0 (3) | ||

| Agea | 42.7 ± 11.4 | 48.7 ± 10.1 | 40.7 ± 7.6 | 41.8 ± 10.9 | F(3, 222) = 7.10 | <.001 |

| Years of educationa | 14.4 ± 2.1 | 13.8 ± 2.5 | 13.2 ± 2.7 | 12.0 ± 3.0 | F(3, 222) = 4.54 | .004 |

| Number of DSM criteria for pathological gamblinga | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 8.7 ± 3.5 | F(3, 222) = 8.06 | <.001 |

| Annual income b | $43,000 ± 35,250 | $35,000 ± 35,500 | $36,500 ± 49,305 | $22,100 ± 23,463 | F(3, 222) = .90 | .44 |

| Addition Severity Index scoresa | ||||||

| Medical | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | F(3, 222) = 8.94 | <.001 |

| Employment | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | F(3, 220) = 2.12 | .10 |

| Gambling | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | F(3, 222) = 2.69 | .05 |

| Alcohol | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | F(3, 222) = 1.65 | .18 |

| Drug | 0.0± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | F(3, 222) = 4.18 | .007 |

| Legal | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | F(3, 222) = 4.31 | .006 |

| Family | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | F(3, 222) = 1.65 | .18 |

| Psychiatric | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | F(3, 222) = 1.49 | .22 |

| Past month days gambled a | 11.0 ± 9.3 | 11.0 ± 9.5 | 17.3 ± 10.9 | 18.8 ± 11.4 | F(3, 222) = 3.76 | .01 |

| Past month money spent gambling b | $1,400 ± 3,575 | $1,266 ±2,441 | $2,650 ± 7,481 | $520 ±2,292 | F(3, 222) = 2.55 | .06 |

Mean ± standard deviation

Median ± interquartile range; values log transformed prior to analyses. Specific groups that differ from one another in post-hoc tests are described in the Results section.

In regards to ASI scores, females with ASPD scored higher than the other groups on the medical and drug scales. Males with ASPD scored higher than males without ASPD on the gambling scale, but no differences were observed among the other groups. Males with ASPD scored higher than females with and without ASPD on the legal section of the ASI. Lastly, gamblers with ASPD, regardless of sex, gambled more days in the past month than gamblers without ASPD.

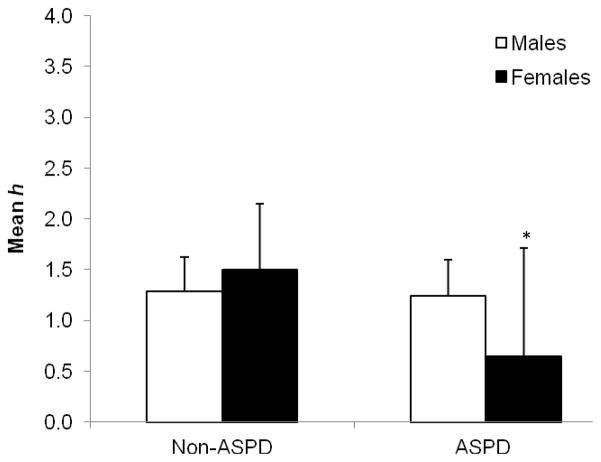

A UNIANOVA evaluated the association between ASPD status and logged probability discounting rates. The model included independent variables that were not significantly correlated and that differed between patients with and without ASPD: sex, age, years of education, ASI gambling scores, and ASI drug scores. Marital status, employment, and ASI medical and legal scores were omitted from the analysis because they were collinear with other variables. All the gambling severity indices were significantly correlated so only one was included (ASI gambling scores) in the model. Sex was entered into the model as a fixed effect and the others as covariates. Neither sex nor any of the covariates were significantly associated with logged probability discounting rates, all ps > .21. However, ASPD status was significantly related to logged probability discounting rates, F(1, 218) = 4.59, p = .03, and a significant interaction between ASPD status and sex was observed, F(1, 218) = 4.03, p = .04. Figure 1 depicts the probability discounting rates based on ASPD status and sex. Among gamblers without ASPD, the mean (SE) h-value was 1.29 (0.33) for males and 1.50 (0.36) for females. Among gamblers with ASPD, the mean h-value was 1.24 (0.65) for males and 0.65 (1.06) for females.

Figure 1. Probability discounting values (h).

Mean h estimates obtained by male (white bars) and female gamblers (shaded bars), presenting with and without antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). Error bars represent standard errors. The asterisk refers to p < .05. For this figure, h-values were reverted to their natural scale in order to ease interpretation.

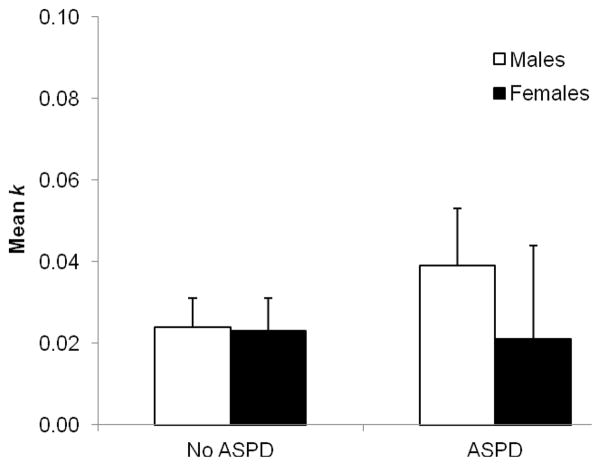

A second UNIANOVA evaluated the association between ASPD status and logged delay discounting rates, using the same independent variables as the model described above. Delay discounting rates were negatively associated with education, F(1, 218) = 5.42, p < .02, and positively associated with ASI gambling scores, F(1, 218) = 6.34, p < .01. However, no other variables, including ASPD status, sex, and the interaction between sex and ASPD status, were related to delay discounting, all ps > .28. Figure 2 depicts k-values for participants with and without ASPD based on sex. The mean (SE) delay discounting rates for male and female gamblers without ASPD were 0.024 (0.007) and 0.023 (0.008), respectively. For males and females with ASPD the respective rates were 0.039 (0 .014) and 0.023 (0.023).

Figure 2. Delay discounting values (k).

Mean k estimates obtained by male (white bars) and female gamblers (shaded bars), presenting with and without antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). Error bars represent standard errors. For this figure, k-values were reverted to their natural scale to ease interpretation.

Discussion

A significant main effect of ASPD status, and an interaction between sex and ASPD status, emerged in terms of discounting rates for probabilistic rewards. Females with ASPD discounted probabilistic monetary outcomes at a lower rate than males with ASPD, and at a lower rate than individuals of both sexes who did not have an ASPD diagnosis. Because lower discounting rates reflect greater subjective value for probabilistic outcomes (i.e., greater tendency to take risks), these results indicate that female pathological gamblers with ASPD are particularly impulsive when it comes to preferring probabilistic rewards. These results are consistent with those from epidemiological and substance abuse treatment samples (Alegria et al., 2013; Goldstein, et al., 1996; 2007; Lewis & Bucholz, 1991) that suggest females with ASPD exhibit greater severity of psychopathology than their male counterparts with ASPD, and these findings extend these problem areas to impulsive probabilistic decisions in female pathological gamblers.

Interestingly, no effects of ASPD or sex were noted in terms of delay discounting. Delay and probability discounting measure distinct aspects of impulsivity (see Green & Myerson, 2010 for a review), and they are not closely linked (e.g., Andrade & Petry, 2012; Holt et al., 2003; Myerson et al., 2003; Reynolds et al., 2004). Results from this study similarly found low correlations between logged probability and logged delay discounting rates, r (226) = −0.018, p = .78. Although the aspects of impulsivity most closely tied to ASPD are not well understood, results from this study suggest that probabilistic decisions may be more impacted by ASPD than decisions about sooner versus more delayed outcomes, at least among pathological gamblers, and female pathological gamblers with ASPD in particular.

Although this study provides some potentially interesting results with respect to sex differences and ASPD, the results should be interpreted within the context of a few limitations. First, no control group of non-pathological gamblers was included. Thus, these results only relate to individuals who are already known to discount at different rates—pathological gamblers. Sex differences in ASPD expressions related to these or other aspects of impulsivity may differ for individuals without a comorbid axis 1 disorder, although few individuals with ASPD do not have other psychiatric conditions. The lack of a control group without pathological gambling may also account for the similar delay discounting rates observed in this investigation. That is, given that whole sample was composed of pathological gamblers, it is possible that the range of delay discounting rates might have been restrained, which could potentially make it more difficult the detection of delay discounting differences based on sex and ASPD status.

Second, the sample size of individuals with ASPD was small, especially when subdivided by sex. Given the low prevalence rate of this personality disorder in women, only ten women were identified with ASPD in this sample, and future studies will probably also have difficulties finding large numbers of women with ASPD. Despite the small number of females with ASPD in this study, the effect that was observed seems to be robust given that it was significant with a small sample size. All ten (100%) of the females with ASPD had h-values below the mean of the other participants in this study and below the mean of non-substance using, non-problem gambling controls in another study using the same probability discounting procedure (Madden et al., 2009). These data suggest that female pathological gamblers with ASPD exhibit very impulsive choices with respect to preferences for probabilistically unlikely outcomes.

Despite the small sample of females with ASPD, this study was comprised of an overall large sample of pathological gamblers. The prevalence rates, and sex distributions, of ASPD were similar to those reported in other samples of pathological gamblers (Bondolfi et al., 2000; Petry et al., 2005). Thus, these results are likely generalizable to pathological gamblers. Established measures of discounting were administered, and discounting rates were within the ranges of those reported in similar samples using these techniques (e.g., Andrade, Alessi, & Petry, in press; Madden et al., 2009).

Gambling may be the prototypical natural expression of probability discounting, so evaluation of these phenomena in pathological gamblers is a unique strength of this study. Women appear to have different etiologies and trajectories than men with respect to the development of gambling problems (Blanco et al., 2006; Grant & Kim, 2002), and sex differences may be especially pronounced in women with ASPD, who appear to be particularly inclined toward impulsive probabilistic decisions. A greater understanding of sex differences in ASPD might ultimately help guide the selection of more effective sex-specific prevention programs and treatment interventions. For example, women may respond less well to gambling treatment than men (Petry et al., 2006), and interventions that focus on increasing impulse control might be useful for women with ASPD.

In substance abuse samples, the broadly defined concept of impulsivity has been found to predict treatment success (Moeller et al., 2001; Patkar et al., 2004). However, given the multidimensional nature of this construct, it is not yet completely clear which dimension(s) account for this relationship, and if this relationship also exists in the context of gambling treatment. Only one study (Petry, 2012) has evaluated the association between delay and probability discounting and gambling treatment outcomes, and only the latter form of discounting was found to be predictive of gambling treatment outcomes. These results are in line with the current findings suggesting that probability discounting may be a more sensitive metric of impulsivity than delay discounting among pathological gamblers. Futures studies could evaluate if probability discounting is also predictive of substance use treatment success among female patients with comorbid ASPD disorder. Furthermore, future investigations in this population might also try to replicate the current findings using different discounting procedures. In this study, we assessed discounting for probabilistic rewards with exclusive gains, but new studies could assess discounting for losses with chances of gain, which is a construct that seems more equivalent to gambling.

In summary, females with pathological gambling and ASPD are substantively impulsive with respect to preferences for high stakes low probability outcomes, but not in terms of exhibiting an inability to delay gratification. An improved understanding of probability discounting might help elucidate important and distinct aspects of ASPD and gambling in both males and females, including prevention programs and treatment interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research and preparation of this report were supported in part by NIH grants: P30- DA023918, R01-DA027615, P50-DA09241, P60-AA03510, R01-HD075630, R01-DA021567, R01-MH60417, and T32-AA07290.

References

- Alegria AA, Blanco C, Petry NM, Skodol AE, Liu S-M, Grant B, Hasin D. Sex differences in antisocial personality disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031681. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LF, Alessi SM, Petry NM. The effects of alcohol problems and smoking on delay discounting in individuals with gambling problems. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.803645. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LF, Petry NM. Delay and probability discounting in pathological gamblers with and without a history of substance use problems. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2508-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Hasin DS, Petry N, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Sex differences in subclinical and DSM-IV pathological gambling: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological medicine. 2006;36(07):943–953. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondolfi G, Osiek C, Ferrero F. Prevalence estimates of pathological gambling in Switzerland. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101:473–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101006473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cale EM, Lilienfeld SO. Sex differences in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1179–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Price RK, Compton WM, Magers DE. Subtypes of adult antisocial behavior among drug abusers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:154–161. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Flory JD, Acheson A, McCloskey M, Manuck SB. IQ and nonplanning impulsivity are independently associated with delay discounting in middle-aged adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline follow-back reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consultation and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R, Powers SI, McCusker J, Mundt KA, Lewis BF, Bigelow C. Gender differences in manifestations of antisocial personality disorder among residential drug abuse treatment clients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;41:35–45. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Compton WM, Pulay AJ, Ruan W, Pickering RP, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Antisocial behavioral syndromes and DSM-IV drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Kim S. Gender differences in pathological gamblers seeking medication treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43:56–62. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.29857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Steinberg MA, Kim SW, Rounsaville BJ, Potenza MN. Preliminary validity and reliability testing of a structured clinical interview for pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research. 2004;128:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. Experimental and correlational analyses of delay and probability discounting. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock MN, Meyer RE, Keener JJ. Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:1050–1055. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DD, Green M, Myerson J. Is discounting impulsive? Evidence from temporal and probability discounting in gambling and non-gambling college students. Behavioural Processes. 2003;64:355–367. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson N, Winters K, Schaffer H. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Marakovic NN. Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: rates decrease as amounts increase. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 1996;3:100–104. doi: 10.3758/BF03210748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard C, Mulvey K, Gastfriend D, Shwartz M. The addiction severity index: A field study of internal consistency and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (The SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. Evaluation of patients treated for pathological gambling in a combined alcohol, substance abuse, and pathological gambling treatment unit using the Addiction Severity Index. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1017–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. Modifying the Addiction Severity Index for use with pathological gamblers. American Journal of Addiction. 1992;1:240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CE, Bucholz KK. Alcoholism, antisocial behavior and family history. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:177–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Johnson PS. Pathological gamblers discount probabilistic rewards less steeply than matched controls. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:283–290. doi: 10.1037/a0016806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. Tests of an equivalence rule for fixed and variable reinforcer delays. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1984;19:426–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith JE, Evans F, Barr HL, O'Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Sakai JT, Booth RE. Gender similarities and differences in antisocial behavioral syndromes among injection drug users. The American Journal On Addictions. 2007;16(5):372–382. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J. The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura Y, Takahashi T, Kitamura N. Discounting delayed and probabilistic monetary gains and losses by smokers of cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182:508–515. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Spiegel DK. Concerning least squares analysis of experimental data. Psychological Bulletin. 1969;72:311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Murray HW, Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Vergare MJ. Pre-Treatment Measures of Impulsivity, Aggression and Sensation Seeking Are Associated with Treatment Outcome for African-American Cocaine-Dependent Patients. Journal Of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23:109–122. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Pathological gamblers, with and without substance abuse disorders, discount delayed rewards at high rates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:482–487. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Validity of a gambling scale for the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000071589.20829.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Gambling and substance use disorders: current status and future directions. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10550490601077668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of probabilistic rewards is associated with gambling abstinence in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:151–159. doi: 10.1037/a0024782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Ammerman Y, Bohl J, Doersch A, Heather G, Kadden R, Steinberg K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:555–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Casarella T. Excessive discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers with gambling problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kirby KN, Kranzler HR. Effects of gender and family history of alcohol dependence on a behavioral task of impulsivity in healthy subjects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: relations to drug use and gambling. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17:651–667. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280115f99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Richards JB, Horn K, Karraker K. Delay discounting and probability discounting as related to cigarette smoking status in adults. Behavioural Processes. 2004;65:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant MN, Bornovalova MA, Trotman AJM, Fishman S, Lejuez CW. Facets of impulsivity in the relationship between antisocial personality and abstinence. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shead NW, Callan MJ, Hodgins DC. Probability discounting among gamblers: differences across problem gambling severity and affect-regulation expectancies. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R. Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Trait impulsivity and response inhibition in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock J, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. Behavioral assessment of gambling: An application of the timeline follow-back method. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:72–80. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]