Abstract

This study examines older adults’ fears of diabetes complications and their effects on self-management practices. Existing models of diabetes self-management posit that patients’ actions are grounded in disease beliefs and experience, but there is little supporting evidence. In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with a community-based sample of 74 African American, American Indian, and white older adults with diabetes. Analysis uses Leventhal’s Common Sense Model of Diabetes to link fears to early experience and current self-management. Sixty-three identified fears focused on complications that could limit carrying out normal activities: amputation, blindness, low blood glucose and coma, and disease progression to insulin use and dialysis. Most focused self-management on actions to prevent specific complications, rather than on managing the disease as a whole. Early experiences focused attention on the inevitability of complications and the limited ability of patients to prevent them. Addressing older adults’ fears about diabetes may improve their diabetes self-management practices.

Keywords: Rural, qualitative methods, common sense model

Introduction

About 18.8 million people in the US have been diagnosed with diabetes, half of whom are 65 years of age or older. Major complications of diabetes include cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, blindness, and lower extremity amputation (CDC, 2011). Heart disease is the most prevalent complication for older adults 65 and older and causes three-quarters of diabetes-related deaths.

Successfully managing diabetes to delay the onset of complications requires medical care, as well as an array of personal care behaviors, including self-monitoring of blood glucose, self-foot checks, and adherence to diet, physical activity, and medication regimens. Implementing these self-management behaviors reduces the risk of diabetes complications (CDC, 2011). However, many older adults with diabetes fail to practice appropriate self-management (Bell et al., 2005a; Skelly et al., 2005). Older adults, particularly those of racial and ethnic minority groups, face challenges in managing their diabetes; including limited physical function, lack of transportation (Arcury, Preisser, Gesler, & Powers, 2005a; Park et al., 2010; Strauss, MacLean, Troy, & Littenberg, 2006), access to grocery stores (Homenko, Morin, Eimicke, Teresi, & Weinstock, 2010), limited facilities for physical activity (Shores, West, Theriault, & Davison, 2009), and lack of health care resources (Bell et al., 2005b).

Beyond restrictions in resources, failure to practice adequate self-management of diabetes may be linked to the underlying belief structure of older adults concerning diabetes. However, little information exists regarding the beliefs of older adults regarding diabetes and the impact these beliefs have on diabetes management strategies. Although a significant body of research focusing on older adults with diabetes exists, much of this work has examined the impact of ethnicity and culture on disease management. A limited body of research about African Americans has focused on beliefs about diabetes (Carter-Edwards, Skelly, Cagle, & Appel, 2004; Jones, Weaver, Grimley, Appel, & Ard, 2006; Koch, 2002), perceptions of health in relation to symptoms (Leeman, Skelly, Burns, Carlson, & Soward, 2008; Stover, Skelly, Holditch-Davis, & Dunn, 2001), the development of culturally sensitive instruments (Utz et al., 2008), and the impact diabetes has on family roles (Samuel-Hodge, Skelly, Headen, & Carter-Edwards, 2005). Research about older adults in general has focused on levels of access to diabetes care and resources, as well as various attempts at different exercise and educational interventions (Brennan, Jr., 2002; Lerman, 2005; Rafique & Shaikh, 2006).

Understanding the beliefs that older adults have regarding diabetes and diabetes complications is an important component in guiding the development and implementation of provider-initiated and self-management strategies and goals. Attempts at changing behavior, which are often the focus of diabetes-centered interventions, typically overlook understanding the beliefs of the person with the disease.

This analysis identifies fears older adults have about the consequences of diabetes. Focusing on fears provides access to core beliefs older adults have about their disease, and uncovers motivation behind how they prioritize their self-management routine. Through prioritization, the complications they fear get the most attention, often eliminating additional management needs altogether. Individuals may not be conscious of the impact their fears have on their disease management, and the health risks they take daily to prevent them by ignoring additional management needs. Understanding fears offers the potential to influence the core beliefs on which older adults in this study base their self-management.

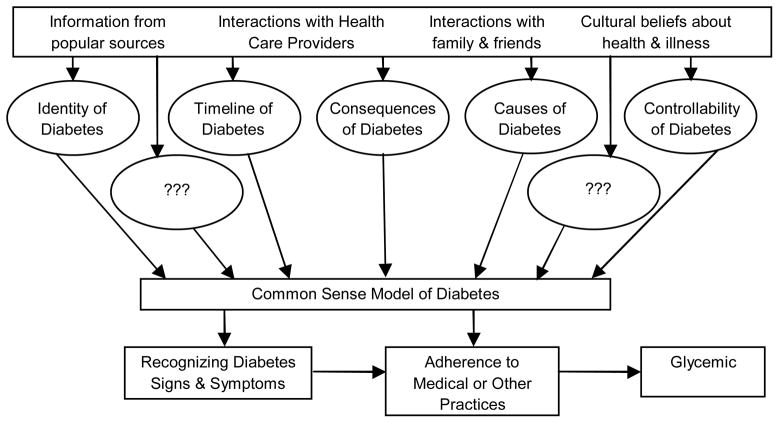

To understand these fears, we utilize Leventhal’s Common Sense Model of Illness (CSM), which identifies different inputs and processes individuals use to define and understand the world. The CSM consists of five domains: the identity or label of the condition; its timeline or duration; the consequences or expected outcomes; the cause; and control or treatment efficacy (Leventhal, Leventhal, & Contrada, 1998).

Superimposing these five domains to represent a CSM of diabetes suggests that older individuals learn what diabetes means, both medically and socially (Figure 1). They seek information about the duration of the disease, which, in the case of diabetes, is chronic in nature. They learn about the short- and long-term consequences of diabetes and the causes of the complications. Based on the CSM, as individuals come across new information about diabetes, they continually assess and reassess this information, transforming their ideas about diabetes. Finally, they learn how to manage the disease through medical intervention and individual action.

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of older adults’ common sense model of diabetes and its role in diabetes self management, based on Leventhal and colleagues ideas of self-regulation and chronic disease (Leventhal et al., 1998, 2008).

The CSM posits that people learn about their disease through a lifetime of experiences, and from interactions with health care providers, family, and friends. How older adults come to self-manage their diabetes depends on how they interpret information and construct their individualized models. Each individualized CSM includes ideas about what diabetes is, what causes it, how long it will last, the consequences and complications that may develop, and the manageability of the disease. This information forms the foundation of what older adults believe about their disease, influencing how they recognize signs and symptoms of diabetes, interpret and adhere to medical practices, and manage their glucose levels.

Translating the CSM into a framework to understand how individuals develop diabetes beliefs provides an opportunity to address the three goals: to document beliefs about long-term consequences of diabetes held by older adults, particularly what complications are most salient; to illustrate how beliefs shape self-management of diabetes; and to examine the development of the older adults’ concerns about diabetes consequences.

Research Design and Methods

Sample

African American, American Indian, and white men and women aged 60 years and older were recruited from three rural counties in North Carolina. Only those who had had diabetes for at least two years were recruited to obtain a sample with enough experience of diabetes to develop beliefs and self-management practices. Participants were recruited without regard to type of diabetes, except that women whose only diagnosis of diabetes was gestational diabetes were excluded. The counties were chosen for large minority populations and high proportion of the population below the federal poverty line. They represent variation on the urban-rural continuum (http://www.ers.usda.gov); All have extensive open country, rural areas. One is part of a metropolitan area with an urban population of 2,500–19,999, one is a nonmetropolitan county with urban population of 20,000+, and one is a nonmetropolitan county with urban population of 2,500–19,999. All three counties have an agrarian history; American Indians are from non-reservation tribes.

The sampling plan was designed to recruit equal numbers of participants for each ethnic/sex cell, with each cell having participants spread evenly across educational attainment categories (less than high school, high school, more than high school). Interviews were stopped at minimum of 11 per cell because ongoing analysis showed that saturation had been reached (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006; Patton, 2002). The final sample included 23 persons with less than a high school diploma, 18 who had a high school diploma or GED, and 33 with more than a high school education. The last group was larger than targeted. This reflected the fact that it included any post-secondary education, ranging from vocational training (e.g., beauty school, welder’s training) through college degrees.

Site-based sampling was used to achieve a representative sample of older adults (Arcury & Quandt, 1999). Sites are places or services used by population members. They included six government offices, five community organizations, three senior recreation centers, one non-subsidized and five subsidized senior apartment complexes, three businesses, thirteen congregate meal sites, five civic organizations, five community leaders, and two churches. Study staff spent time in these sites over the past 12 years as part of ongoing mixed methods research projects (Bell et al., 2005a; Brewer-Lowry, Arcury, Bell, & Quandt, 2010; Quandt, Arcury, McDonald, Bell, & Vitolins, 2001; Quandt et al., 2005). Sites were first identified and then older adults recruited within the participants, clients, or residents of each. Formal and informal community leaders helped with study recruitment.

Data Collection

From May through November 2007, in-depth interviews ranging from 1 to 3 hours were conducted in the homes of 74 respondents. Interviewers obtained informed consent. An incentive ($10) was offered for completing the interview. Procedures were approved by the University’s institutional review board (Protocol # 00000685).

The interview guide was semi-structured, and the interview lasted 60–90 minutes. The questions and probes focused on questions about diabetes beliefs, knowledge, consequences, and symptom self-management. Questions specific to this analysis included general questions asking participants to list and discuss any diabetes-related complications with which they were familiar. Participants were also asked which diabetes complications concerned them the most. The guide was reviewed and revised throughout the interview process in order to include emerging insights.

Data Analysis

Data analysis used a systematic, computer-assisted approach (Atlas ti 6.0; Cologne, Germany). Each interview was transcribed verbatim and edited for accuracy. A preliminary codebook was developed based on the interview guide, and additional codes and broad themes to characterize participants. Codes fell into nine domains: causes, consequences, symptoms, how to control symptoms, diabetes treatment, diabetes physiology, cure and control, attitudes towards diabetes, and sources of diabetes information.

For this paper, domains of consequences and symptoms were reviewed. Word searches (e.g., fear, amputation, blind) to gather data on fears, diabetes management, and family were used. Many searches developed into individual codes including when/how the participant first heard about diabetes, and how participants manage complications. The analysis was completed by returning to the original transcripts and looking for data that had not emerged in any of the previous attempts. Exemplary quotations presented are identified by respondent number (R#), ethnicity (AA, AI, W), and sex (F, M).

Results

This analysis is based on a subsample (Table 1) of 63 participants who expressed fear of specific long-term consequences of diabetes. These included individuals with a broad range of diabetes experience: 41 were on oral medications, 13 were on insulin, 5 were on both oral medications and insulin, and 4 were on no medication for diabetes. The four most salient consequences listed, in order of frequency of mention, were: amputation, low blood glucose resulting in a coma, blindness, and the progression of diabetes. Table 1 shows the distribution of fears by sex and ethnicity. African American and white women and white men appeared to express the most fears. The 11 with no fears were spread evenly across sex/ethnic categories. They did not differ from those with fears in medication use or duration of diabetes, but had fewer than expected in the post-high school education category (data not shown).

Table 1.

Distribution of fears reported by sex and ethnic group.

| Fear | Female | Male | Total Reporting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA1 N=14 |

AI N=13 |

W N=12 |

AA N=11 |

AI N=12 |

W N=12 |

||

| Amputation | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 18 |

| Low blood glucose and coma | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 14 |

| Blindness | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| Progression of disease (insulin, dialysis) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| No fears reported | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

AA=African American, AI=American Indian, W=White

The long-term consequences of diabetes salient to older adults

All participants considered amputation a major consequence of diabetes. About a third stated that the fear of amputation frightened them the most about their diabetes.

It’s hard to get sores cured…and just keeps you scared all the time…whether you are going to lose some of your limbs. Things like that’s scary for me. R26-AI-F

I have a cousin that had [gangrene] and lost toes and everything. That’s the biggest problem to be worried about, losing a limb, you know. R03-AA-F

To avoid amputation, some participants changed their regular activities. One American Indian man was so afraid of getting a wound that could lead to amputation that he gave up his hobby of working on trucks.

When participants talked about problems that could lead to amputation, they reported a great deal of fear because they knew that the final stage in the treatment plan was amputation. In addition to the actual trauma of losing a limb, they were concerned that an amputation would reduce their ability to function independently.

All 63 older adults mentioned vision loss as a potential diabetes complication. About a quarter identified going blind as the long-term consequence they most feared.

I was always afraid of--I said, “Lord, I want to see as long as I live if I can.” R59-W-M

[I fear] the possibility I might lose my eyesight a little quicker, which I hope I don’t. My mother was legally blind in one eye and just about blind in the other one when she passed away, so I’m very conscious about my eyes. Because I know if I lose my sight, I’m the only one that’s going to take care of me. R11-W-F

For one older adult, a family history of diabetes-related blindness and memories of watching her grandmother lose her sight now haunt her as she realizes it could one day happen to her.

Some participants only began to take diabetes seriously when it affected their vision.

I didn’t know what having diabetes carried along with it until I got blurred vision… I had to learn the hard way. I didn’t believe it. R17-W-M

Older men were concerned about losing their independence due to vision problems: losing their sight would mean they could no longer drive.

[My friend] gave [the Department of Transportation] his license, and he can’t drive, so I think that almost killed him…. I don’t know what I’d do if I couldn’t drive. That would affect me more than the diabetes…. But… these things happen. You can see it around you. R70-AA-M

The loss of independence resonated most strongly with those afraid of going blind.

About a quarter of participants were afraid their blood sugar would drop unexpectedly while they were taking a nap or sleeping at night, causing them to slip into a coma.

I’m scared to go to bed at night, if it drops on me, because I like went into a coma a couple of times. R47-AA-F

Yeah, I get up and I can’t stand it. Knowing that I’ve got sugar and I could go in a coma or something like that. I just get scared. R38-AI-F

Participants also feared low sugar during the day. When their blood sugar begins to drop, they either do not recognize symptoms until it is too late, or cannot function well enough to take actions to raise blood sugar levels.

Because that’s one of the fears, you know, not having enough sign that I recognize it. R02-W-F

Coma, I’ve always been afraid of that. Because, I can handle high sugar better than I can low sugar because when I get, when that sugar gets that low I start to getting nervous, sweaty, and all that on the inside. R59-W-M

In addition to personal experience with low blood sugar episodes, most participants concerned about coma had witnessed someone experience a low sugar episode or go into a diabetes-related coma.

[My] husband had it [diabetes]. He had it real bad. He had to take a pill, and the shots…went into a sugar coma, and he died. R10-AI-F

I think [diabetes is] very serious. Very serious. Because like I say, if you don’t eat right, it [glucose level] will go too low. You could go in a coma, because my brother went in a coma, because his got real low. R19-AA-F

The group who worried about low blood sugar expressed less concern about loss of independence than did those afraid of amputation or blindness. In fact, many of them talked about wanting family around for comfort and safety.

If I lay down [my husband] won’t let me go to sleep. He’ll keep, you know, you can go into a coma. I almost went into one one time… he keeps check on me. Usually if I feel bad I lay here where he can see me. R45-AI-F

For fourteen of the older adults, most feared the progression of their diabetes starting with having to go on insulin, or “going on the needle”.

Pills, pills, I take pills all the time. That’s just normal you know, me taking a lot of medication and my diabetes medication is just like me taking another pill, as far as I’m concerned. But insulin is a whole new chapter. R13-AA-M

Well, see that’s what I say, like it gets worse. When people first find out about diabetes, like they call it diabetes number 2, you’re taking the pills and all for a long time, but after that they start taking the needle, that’s getting worse… They take off their toe, then they have to take off the feet, then they have to take off the leg. R48-AA-M

Some in this group also feared going on dialysis. For one man, the fear was so great that he would rather die than extend his life with treatment.

[Doctor] mentioned to me a few weeks ago that I might have to go on dialysis. I just flat told the doctor if I was going to die, let me die because I wasn’t going to go on it. My wife’s momma went on it; she didn’t live long. My momma went on it, didn’t live long. So like I told him, I wasn’t going on it. R71-AI-M

Participants talked about their family and friends being on dialysis. Nine participants mentioned specific friends and family members who had to undergo dialysis treatments. For some participants, observing the dialysis experiences of friends and family led to an increased determination to manage diabetes:

I wish I’d have took care of [my diabetes] better long time ago as good as I’m doing now. I’m respecting it now.

I have some friends that had limbs amputated, and on dialysis, so I take it very seriously. R70-AA-M

Fears about complications affect self-management

For all fears, participants directed self-management more toward symptoms of the complication they feared rather than managing blood sugar, the underlying cause of the complication. When those who feared amputation talked about preventing amputation, they emphasized their routine of activities to manage cuts and sores and motivation for wearing special shoes:

Check your feet. Make sure you take that mirror and look in between your toes to see that you ain’t got no cracks or cuts in between your toes. R05-AA-F

[I] always wear shoes, even in the house, because [the doctor] said I could step on something and not know it, and you know it would hurt my feet, and it would cause gangrene, and that’ll cause amputation. R46-AA-F

When [my husband] had his first leg amputated…he had stepped on a rusty nail and he didn’t know that he had stepped on a nail. So, he ended up with gangrene in the foot. R15-AA-F

Those fearing blindness mentioned two ways to prevent the permanent deterioration of their vision: an eye examination to see if they needed stronger glasses so their vision would not blur or stronger medication to prevent blurry vision.

Oh, I just have to be careful because I wear glasses and if it [vision] gets real bad, and keeps bothering me, I go to an optician and get my eyes checked… Yeah, just to see if they’re getting worse, or if I’ve got to get stronger glasses or whatever. R21-W-F

If that’s starting [vision is getting worse] and you get, you get medication or something before it sets in permanent, then I think you can, there’s some reversing, but once it’s set in like mine is, I don’t know of anything that you can do to prevent it. R29-AI-F

There was no mention of controlling blood sugar through dietary intake or exercise as methods to manage and prevent long-term vision changes.

Those who feared going into a coma believed the most important action to take was to test their sugar prior to going to bed or in the morning and reacting to the reading.

Well, yes, that’s why I get afraid. Like if I take, if I prick my finger and my sugar is below 120 before I go to bed, you better believe I’m going to eat something sweet because I’m going to be afraid I’m going to go into a coma while I’m sleeping. R58-W-F

I don’t take my pill every day now. When my sugar is low - I test my sugar every morning. If my sugar comes down to 70, I don’t take that pill. When I eat I check it again make sure. If it’s up, then I take my pill. If my sugar is low, I don’t take that pill. It might make me high. So, you know, if your sugar is too low, you’ll go in a coma. R19- AA-F

While these participants paid close attention to the glucose level at certain times, they managed a potential incident rather than the disease in general.

Those who feared going on the needle or dialysis focused on avoiding different foods and taking medicine or using home remedies to prevent their diabetes from getting worse.

Juices, sodas, and all that different stuff. I don’t mess with it because I can get along without it, and I don’t want to lose a kidney. R20-AA-F

Sometimes I go in and take me a little taste of vinegar in a teaspoon, about [an inch] in a little water. I drink [vinegar] and it kills [high blood glucose] …It’ll knock it away…It does it good. R18-AI-F

Others felt they had no control over what was going on in their bodies, so the disease could progress to insulin or dialysis.

But the whole thing with diabetes is that you can have the same food day after day after day, and your glucose readings would be wildly different day after day after day. So controlling diabetes is certainly a question mark. It controls you rather than you control it. R46-W-M

The origin of diabetes fears

Prior to diagnoses, the participants witnessed someone they knew experience the diabetes complication they came to fear. How and when they first learned about diabetes and first witnessed complications had a significant impact on their perceptions of the disease.

Oh, I would have been a young boy, and I didn’t know what it was. My grandfather was a diabetic, and it began to affect him. Then, when I got a little older I learned what], having sugar was. Then my dad, I think in the early ‘50’s, mid ‘50’s was diagnosed with, as being a diabetic so from the, being a teenager I learned about being a diabetic. R29-AIM

Participants who learned about diabetes when they were young explained that, outside of overhearing talk about the new diagnosis, the most recent complication, or recent death, they learned little about diabetes from their family.

Well, I didn’t know much about it [diabetes] because you know, she [grandmother] died when I was fairly young, and nobody talked about it very much. Nobody knew much about it back then. R31-W-M

While there was very little discussion or intentional passing of information about diabetes, they gleaned pieces of information about the consequences of diabetes by witnessing the disease’s effects.

Through observation, participants learned that people with diabetes could go blind, but had no idea why, or how to prevent it. They learned that many people with diabetes lost their limbs because of infected cuts or sores, but learned nothing about how to encourage healing through glucose management. Those fearful of low blood glucose and slipping into a coma were the one group that was successful in managing an episode to return their sugar to normal. However, there was still uncertainty for this group, because they had ongoing problems keeping their blood sugar stable. Finally, the older adults learned that once someone with diabetes went on insulin, he or she had little time left to live, but they had no concrete idea about how to prevent going on insulin in the first place, or how to prolong life. Witnessing the impact diabetes consequences could play in their lives instilled a sense of fear, enhanced by the uncertainty of not knowing when or why it would happen.

Scary. It’s scary. When you see the results of it [diabetes], like I’ve seen it, and then you realize that same thing is, has come to you, and could happen to you, to me it’s scary. So, if that’s not a strong enough term, I don’t know what term to use. R29-AI-M

Defining the overall state of their diabetes based on the state of one complication shifted the participants’ efforts from managing diabetes as a disease to managing the individual symptoms associated with the most-feared complication.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that, in this group of participants, older adults with diabetes hold fears of several key consequences of diabetes: amputation, blindness, coma, and disease progression. These beliefs appear to be grounded in early life experiences and form the basis for each individual’s self-management. Self-management behaviors are directed more toward the most-feared complication than to the overall control of diabetes. Women seem to express more fears than men, perhaps due to their experiences and observations as care givers.

The current impacts of diabetes on healthcare and quality of life create a serious public health burden. Therefore, research should focus on factors that influence diabetes management, including beliefs that persons with diabetes have about the disease and its consequences. Research exists on beliefs about the consequences of diabetes (Brod, Kongsø, Lessard, & Christensen, 2009; Ellish, Royak-Schaler, Passmore, & Higginbotham, 2007; Farmer, Kinmonth, & Sutton, 2006; Herschbach et al., 2005; Irvine, Cox, & Gonder-Frederick, 1992; Mollema, Snoek, Adèr, Heine, & van der Ploeg, 2001), and beliefs about treatment methods (Arcury & Quandt, 1999; Arcury, Skelly, Gesler, & Dougherty, 2006; Jones et al., 2006; Kolasa & Rickett., 2010). The existing literature also contains a substantial amount of research about the beliefs older adults have regarding self-management methods (Arcury & Quandt, 1999; Gorawara-Bhat, Huang, & Chin, 2008; Harvey & Lawson, 2009; Haslbeck & Schaeffer, 2009; Koch, 2002; Tang, Funnell, Brown, & Kurlander, 2010).

The current analysis picks up where others have left off in examining not only older adults’ beliefs about diabetes consequences, or what they fear, but also how those beliefs influence self-management behaviors. Exploring their pasts showed that these older adults have intergenerational connections to their current diabetes self-management behaviors. Linking their earliest memory of the disease to the complications they feared revealed the impact their experiences had on their overall beliefs regarding diabetes self-management.

The existing literature contains little research on fears regarding diabetes. While not specifically focusing on older adults, the most common fears found in a multi-ethnic sample of individuals with diabetes included retinopathy, amputation, nephropathy, neuropathy, and stroke (Hendricks & Hendricks, 1998). However, that study did not examine the source or ramification of these fears.

Despite educational efforts, many people with diabetes are unaware that CVD is the most significant medical consequence of diabetes, the leading killer for persons with diabetes. This is true in the US (Merz, Buse, Tuncer, & Twillman, 2002), and such results have been replicated in other countries (Carroll, Naylor, Marsden, & Dornan, 2003; Lai, Chie, & Lew-Ting, 2007).

Leventhal’s CSM of illness behavior proposes that individuals collect information from different sources throughout their lifetime, process it, store some for future confirmation, and discard the rest (Leventhal, Weinman, Leventhal, & Phillips, 2008). For this analysis, we had the opportunity to draw attention to when the older adults first learned about diabetes and the situations they witnessed of relatives who had diabetes. We were also able to document how some of their earliest experiences continued to play a significant role in their current self-management routine. The reasons these beliefs persist may lie in the fact that typical interactions with health care providers and diabetes educators generally focus on recommending actions and self-care behaviors rather than on challenging diabetes-related beliefs. By challenging the belief behind the behavior, diabetes educators and other diabetes professionals have the opportunity to make meaningful changes in an individual’s diabetes self-management routine.

The participants likely had little information available to them when they first learned about the disease. In contrast, participants now have many sources of diabetes information (e.g., television, websites, print materials), though of varying quality. Some participants recall diabetes before oral medications to promote glycemic control or other self-management tools existed. Viable sources of diabetes information for participants’ parents and grandparents included limited information provided by the medical profession and family or friends.

Using Leventhal’s CSM as a framework for this analysis provided an in-depth look into the information sources that existed for the older adults. The CSM also assisted in constructing a better understanding of the impact those sources had on the development of their beliefs about diabetes. These participants possessed information about diabetes and its outcomes before there was a widespread understanding of the complexity of the disease. While many of the participants stated that no one talked about diabetes “back then,” our evidence shows that what participants learned about diabetes was to play a significant role in their beliefs and ongoing management of their disease.

When the participants were young, they learned that there were specific consequences attached to a diabetes diagnosis that were out of the control of the person with the disease. Blindness, amputation, coma, and death were the complications participants were able to witness in their family members and the ones they ultimately came to fear. The impact of what the older adults witnessed on the self-management of their own diabetes causes two major concerns. The first concern originates in how the older adults attempt to manage and prevent the complications that frighten them the most. In efforts to prevent the complication they fear, participants may be ignoring other primary management tasks necessary to manage their disease as a whole and to prevent CVD, the major complication.

The second concern suggests why these older adults manage their diabetes on such a symptom-specific basis. Through passive learning the older adults absorbed information that informed them that the progression of certain long-term diabetes consequences occurs outside of anyone’s control. Most likely, after their diagnosis, they learned that they have control over many daily symptoms. Combining these two ideas, long-term consequences and daily symptoms exist in parallel, each functioning independent of the other. This inconsistency in the way the past and present are interpreted conforms to Tversky and Kahneman’s work (1974). They argue that people use a so-called heuristic to filter past experience; doing this, they tend to keep the most dramatic or frightening events in their memory as representative of the diabetic experience. In these older adults, what they have learned about treating or avoiding specific symptoms is aggressively applied only to those symptoms that represent the most-feared potential consequence. The notion of overall diabetes management as a way to avoid potential consequences is overlooked in favor of a fear-based, symptom-specific strategy.

Basing self-management on fear can clearly be maladaptive. As older adults with diabetes focus on dramatic outcomes, they may ignore everyday symptoms of glycemic control. Lawson and colleagues point to an even more serious consequence of fears in patients in the UK, totally disengaging from the medical system (Lawson, Lyne, Harvey & Bundy, 2005).

Challenging the belief that management efforts should be focused on a specific, feared outcome is a starting point to developing good overall self-management, potentially preventing both the complications these older adults fear and those they may not have considered. Unfortunately, major barriers exist to changing beliefs. The most challenging barrier is the influence families have on the development of one’s belief system, whether intentional or not. What these older adults learned through watching their relatives experience diabetes complications was memorable enough to be the foundation of their perception of the onset of diabetes long-term consequences years later. Scollan-Koliopoulos and colleagues (2007) refer to this passing of information from one generation to the next as the multi-generation diabetes legacy. They argue that families are often the first diabetes educators; the information they provide often plays a significant role in the development of diabetes beliefs. This bond with the past makes it difficult to get people to take advantage of diabetes education opportunities, because they already feel competent to manage their disease.

Managing multifaceted illnesses like diabetes requires changing behavior in the short term, and changing beliefs for successful long-term management. Fears are rarely talked about, yet they play a critical role in what they believe and how they behave. Fears are often associated with fragmented memories, leaving gaps of information. Attempting to fill in the missing pieces of the fearful memory can bring clarity and understanding, bringing history into focus. The respondents in this study spoke about what diabetes complications worried them the most. In reciting their fears, they underscored the ingrained belief that threatens their overall health as a person with diabetes. Responding to fears in a clinical or educational setting with insight and knowledge may prove to be a slow but successful means of fine-tuning family beliefs and outdated information.

Recommendations

If other studies confirm these findings, diabetes educators and other health care personnel who deal with older adults with diabetes are in a position to use the information from the current study to ensure that older adults’ fears of diabetes consequences do not dictate their self-management practices. They need to ensure that these older adults understand that day-to-day efforts at glycemic control are key to preventing consequences like amputation and blindness. Many older adults receive equipment and supplies for home glucose monitoring paid for by insurance or Medicare. However, we have previously shown that those who have poorly controlled blood glucose have a poorer understanding of how to use this equipment and what their blood glucose should be (Brewer-Lowry et al., 2010). With cognitive function decline, their ability to perform home monitoring and interpret the results may decline over time.

Annual diabetes self-management counseling, available through Medicare, is an opportunity to retarget the diabetes self-management practices of older adults. Practitioners should use this benefit to confront the fears of older adults and provide them the most up-to-date information on how to prevent complications. Other approaches such as group medical visits (Lynch, Estes, & Hernandez, 2005) may also be beneficial in redirecting practices that fail to adequately target appropriate outcomes to reduce future diabetes complications.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG017587.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Protection

This research was approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board, protocol IRB00000685.

Contributor Information

Sara A. Quandt, Email: squandt@wakehealth.edu, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-6015, 336-713-4157 (fax).

Teresa Reynolds, Email: tareynol@wakehealth.edu, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-6722.

Christine Chapman, Email: chrispchapman@yahoo.com, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-6015.

Ronny A. Bell, Email: rbell@wakehealth.edu, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard Winston-Salem, NC 27157 336-716-9736.

Joseph G. Grzywacz, Email: grzywacz@wakehealth.edu, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-2237.

Edward H. Ip, Email: eip@wakehealth.edu, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157 336-716-9833.

Julienne K. Kirk, Email: jkirk@wakehealth.edu, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-9043.

Thomas A. Arcury, Email: tarcury@wakehealth.edu, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, 336-716-9438.

Reference List

- Altizer K, Quandt SA, Grzywacz JG, Bell RA, Sandberg J, Arcury TA. Traditional and commercial herb use in health self-management among rural multiethnic older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi: 10.1177/0733464811424152. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Participant recruitment for qualitative research: A site-based approach to community research in complex societies. Human Organization. 1999;58:128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, Powers JM. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. Journal of Rural Health. 2005a;21:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Skelly AH, Gesler WM, Dougherty MC. Diabetes beliefs among low-income, white residents of a rural North Carolina community. Journal of Rural Health. 2006;21(4):337–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Arcury TA, Snively BM, Smith SL, Stafford JM, Dohanish R, Quandt SA. Diabetes foot self-care practices in a rural triethnic population. The Diabetes Educator. 2005a;31:75–83. doi: 10.1177/0145721704272859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Snively BM, Stafford JM, Smith SL, Skelly AH. Primary and Specialty medical care among ethnically diverse, older rural adults with type 2 diabetes: The ELDER Diabetes Study. Journal of Rural Health. 2005b;21:198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FH., Jr Exercise prescriptions for active seniors: a team approach for maximizing adherence. The Physician & Sports Medicine. 2002;30:19–29. doi: 10.3810/psm.2002.02.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Lowry AN, Arcury TA, Bell RA, Quandt SA. Differentiating approaches to diabetes self-management of multi-ethnic rural older adults at the extremes of glycemic control. The Gerontologist. 2010;50:657–667. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S, Christensen TL. Psychological insulin resistance: patient beliefs and implications for diabetes management. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Naylor E, Marsden P, Dornan T. How do people with Type 2 diabetes perceive and respond to cardiovascular risk? Diabetes Medicine. 2003;20:355–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Edwards L, Skelly AH, Cagle CS, Appel SJ. “They care but don’t understand”: family support of African American women with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2004;30:493–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet, 2011: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ellish NJ, Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Higginbotham EJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about dilated eye examinations among African-Americans. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(5):1989–1994. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A, Kinmonth AL, Sutton S. Measuring beliefs about taking hypoglycaemic medication among people with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2006;23(8):931. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorawara-Bhat R, Huang ES, Chin MH. Communicating with older diabetes patients: self-management and social comparison. Patient Education & Counseling. 2008;72:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JN, Lawson VL. The importance of health belief models in determining self-care behaviour in diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2009;26:5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck W, Schaeffer D. Routines in medication management: the perspective of people with chronic conditions. Chronic Illness. 2009;5:184–196. doi: 10.1177/1742395309339873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks LE, Hendricks RT. Greatest fears of type 1 and type 2 patients about having diabetes: implications for diabetes educators. The Diabetes Educator. 1998;24:168–173. doi: 10.1177/014572179802400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschbach P, Berg P, Dankert A, Engst-Hastreiter U, Waadt S, Keller M, Ukat R, Henrich G. Fear of progression in chronic diseases: psychometric properties of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;58(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homenko DR, Morin PC, Eimicke JP, Teresi JA, Weinstock RS. Food insecurity and food choices in rural older adults with diabetes receiving nutrition education via telemedicine. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2010;42:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine AA, Cox D, Gonder-Frederick L. Fear of hypoglycemia: relationship to physical and psychological symptoms in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychology. 1992;11(2):135–138. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DE, Weaver MT, Grimley D, Appel SJ, Ard J. Health belief model perceptions, knowledge of heart disease, and its risk factors in educated African-American women: an exploration of the relationships of socioeconomic status and age. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association. 2006;17:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J. The role of exercise in the African-American woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus: application of the health belief model. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2002;14:126–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasa KM, Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: A survey of primary care practitioners. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2010;25:502–509. doi: 10.1177/0884533610380057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WA, Chie WC, Lew-Ting CY. How diabetic patients’ ideas of illness course affect non-adherent behaviour: a qualitative study. The British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57:296–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson VL, Lyne PA, Harvey JN, Bundy CE. Understanding why people with type 1 diabetes do not attend for specialist advice: A qualitative analysis of the views of people with insulin-dependent diabetes who do not attend diabetes clinics. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:409–423. doi: 10.1177/1359105305051426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Skelly AH, Burns D, Carlson J, Soward A. Tailoring a diabetes self-care intervention for use with older, rural African American women. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34:310–317. doi: 10.1177/0145721708316623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman I. Adherence to treatment: The key for avoiding long-term complications of diabetes. Archives of Medical Research. 2005;36:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychology & Health. 1998;13:717–733. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Weinman J, Leventhal EA, Phillips LA. Health psychology: the search for pathways between behavior and health. Annual Review Psychology. 2008;59:477–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Estes CL, Hernandez M. Chronic care initiatives for the elderly: can they bridge the gerontology-medicine gap? Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2005;24:108–124. [Google Scholar]

- Merz CN, Buse JB, Tuncer D, Twillman GB. Physician attitudes and practices and patient awareness of the cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;40:1877–1881. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollema ED, Snoek FJ, Adèr HJ, Heine RJ, van der Ploeg HM. Insulin-treated diabetes patients with fear of self-injecting or fear of self-testing: psychological comorbidity and general well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2001;51(5):665–672. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NS, Roff LL, Sun F, Parker MW, Klemmack DL, Sawyer P, Allman RM. Transportation difficulty of black and white rural older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2010;29:70–88. doi: 10.1177/0733464809335597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Arcury TA, McDonald J, Bell RA, Vitolins MZ. Meaning and management of food security among rural elders. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2001;20:356–376. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Bell RA, Snively BM, Smith SL, Stafford JM, Wetmore LK, Arcury TA. Ethnic disparities in glycemic control among rural older adults with type 2 diabetes. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15:656–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafique G, Shaikh F. Identifying needs and barriers to diabetes education in patients with diabetes. Journal Pakistan Medical Association. 2006;56:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel-Hodge CD, Skelly AH, Headen S, Carter-Edwards L. Familial roles of older African-American women with type 2 diabetes: testing of a new multiple caregiving measure. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15:436–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollan-Koliopoulos M, O’Connell KA, Walker EA. Legacy of diabetes and self- care behavior. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30:508–517. doi: 10.1002/nur.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shores KA, West ST, Theriault DS, Davison EA. Extra-individual correlates of physical activity attainment in rural older adults. Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelly AH, Arcury TA, Snively BM, Bell RA, Smith SL, Wetmore LK, Quandt SA. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in a multiethnic population of rural older adults with diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2005;31:84–90. doi: 10.1177/0145721704273229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover JC, Skelly AH, Holditch-Davis D, Dunn PF. Perceptions of health and their relationship to symptoms in African American women with type 2 diabetes. Applied Nursing Research. 2001;14:72–80. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2001.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K, MacLean C, Troy A, Littenberg B. Driving distance as a barrier to glycemic control in diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:378–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander JE. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: An empowerment-based intervention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz SW, Williams IC, Jones R, Hinton I, Alexander G, Yan G, Moore C, Blankenship J, Steeves R, Oliver MN. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34:854–865. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]