Abstract

Objectives

To better understand women's experience with pelvic organ prolapse and to compare this experience between English and Spanish speaking women.

Methods

Women with pelvic organ prolapse were recruited from female urology and urogynecology clinics. Eight focus groups of 6-8 women each were assembled; four groups in English and four in Spanish. A trained bilingual moderator conducted the focus groups. Topics addressed patients' perceptions, their knowledge and experience with pelvic organ prolapse symptoms, diagnostic evaluation, physician interactions, and treatments.

Results

Both English and Spanish speaking women expressed the same preliminary themes: lack of knowledge regarding the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse, feelings of shame regarding their condition, difficulty in talking with others, fear related to symptoms, and emotional stress from coping with pelvic organ prolapse. In addition, Spanish speaking women included fear related to surgery and communication concerns regarding the use of interpreters. Two overarching concepts emerged: first - a lack of knowledge which resulted in shame and fear; and second - public awareness regarding pelvic organ prolapse is needed. From the Spanish speaking an additional concept was the need to address language barriers and the use of interpreters.

Conclusions

Both English and Spanish speaking women felt ashamed of their pelvic organ prolapse and were uncomfortable speaking with anyone about it, including physicians. Educating women on the meaning of pelvic organ prolapse, symptoms, and available treatments may improve patients' ability to discuss their disorder and seek medical advice; for Spanish speaking women, access to translators for efficient communication is needed.

Keywords: Patient Perceptions, Pelvic organ prolapse, Shame, Spanish speakers, Symptoms

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is common; prevalence estimates range from 2.9% to 5.7% among community based women [1]. The number of women with POP is expected to increase by 46% by 2050 [2]. Women with POP may experience not only symptoms, such as vaginal bulging and pressure, but functional challenges related to sexual function, body image, continence, and pain [3–7]. There has been increased interest in the expectations and goals of women undergoing treatment for POP [8–10], but there is very little information on women's perceptions and related health care interactions from when they first received the diagnosis of POP.

According to 2010 Census data, the Hispanic or Latino population is the largest minority group in the United States, comprising 16% of the total population [11]. It is estimated that one in four women in the US will be Latina in the year 2050 [12]. Data also suggest that Hispanic and Caucasian women have a 4–5 times higher risk of symptomatic pelvic prolapse compared to African-American women [13]. Given that the Hispanic population may be at increased risk of POP, the need for more information on how Hispanic women experience their POP is important.

The goal of this study was to better understand both English and Spanish speaking women's experience with pelvic organ prolapse, including their perceptions, symptoms, and related health care interactions.

Materials and Methods

This is a multisite study, conducted at three separate academic Urology and Urogynecology centers, including Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (a non-profit private hospital in Los Angeles), Olive View Medical Center (a public hospital in northern Los Angeles County) and the University of New Mexico (a large academic health complex in Albuquerque, New Mexico). Our goal was to gain patient perspectives of their experience with prolapse and to determine if these perceptions varied between women who spoke English and those who spoke Spanish. IRB/HRRC approval was obtained at each site; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center [CSMC IRB# Pro00025379], Olive View Medical Center [UCLA-Olive View IRB# 10H-884300], and the University of New Mexico [UNMHSC HRRC#11-347]. Patients seen in any of these Urology or Urogynecology clinics were recruited at the time of their initial visit and invited to participate in a 1.5 hour focus group. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) based on physician diagnosis, preferred language of either English or Spanish, age 21 or older, no significant pelvic issues such as pelvic pain or painful bladder syndrome, and no significant psychiatric history.

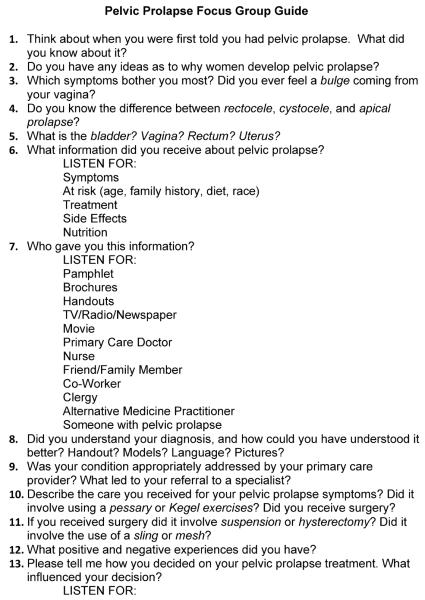

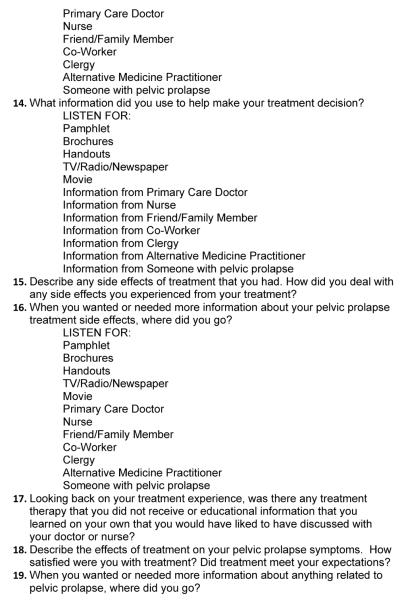

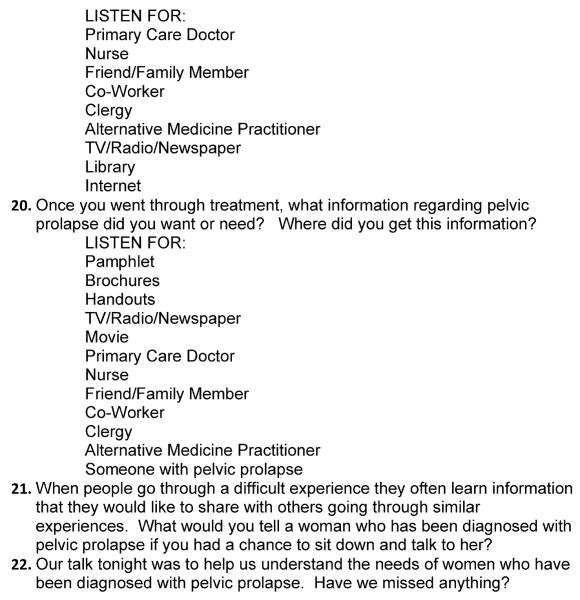

A total of eight focus groups of 6-8 women each were planned, with four groups in English and four in Spanish. Patients were placed in either an English or Spanish focus group based on their preferred language. A single, trained bilingual moderator conducted all of the focus groups and each focus group was for approximately 1.5 hours. A standardized open-ended topical guide in English and Spanish was used to elicit patients' perceptions, their knowledge and experience with pelvic organ prolapse symptoms, diagnostic evaluation, physician interactions, and treatments (See Appendix 1). All focus groups were recorded and transcribed. Focus groups in Spanish were transcribed and translated verbatim by a qualified translator

Qualitative analysis was performed using grounded theory as described by Charmaz [14]. Grounded theory is hypothesis generating. Briefly, this involved line-by-line coding of the transcripts to identify key phrases from the focus group participants' words. These key phrases were naturally grouped together to form preliminary themes, from which emergent concepts arose. Patient quotes were pulled to illustrate and support the preliminary themes and concepts. Three separate researchers independently completed the line-by-line coding to reduce subjectivity. Discrepancies between codes were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Results

Eight focus groups of 6-8 women each were assembled, including four groups in English and four in Spanish. At the University of New Mexico two focus groups were held in English and two focus groups in Spanish. Two English and two Spanish focus groups were performed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Olive View Medical Center, respectively. A total of 58 subjects participated: 25 whose primary language was English and 33 whose primary language was in Spanish. The mean age of the women in the English group was 63.8 years (range 33 – 90 years), the mean age of the Spanish-only group was slightly younger, at 56.6 years (range 46 – 77 years). The majority (80%) of the participants in the English group was from the United States of America and had some college education or higher (72%), the majority of subjects in the Spanish-only group were from Mexico (70%) with only 27% from Central or South America. 69% reported a high school education or less. Table 1 provides complete patient characteristics for the two language groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| English-Speaking | Spanish-Speaking | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (range): | 63.8 years | 56.6 years |

| Country of Origin: | n (%) | n (%) |

| Belize | 2 (8) | 0 |

| Canada | 1 (4) | 0 |

| United States of America | 20 (80) | 0 |

| Chile | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Dominican Republic | 1 (4) | 0 |

| El Salvador | 0 | 5 (15) |

| Guatemala | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Mexico | 0 | 23 (70) |

| Nicaragua | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Not answered | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Education Level: | ||

| No schooling | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Less than high school | 0 | 14 (42) |

| Some high school | 6 (24) | 8 (24) |

| High school diploma | 1 (4) | 2 (6) |

| Some college | 4 (16) | 3 (9) |

| Associate degree | 2 (8) | 1 (3) |

| Bachelor's degree | 6 (24) | 0 |

| Graduate or Professional degree | 5 (20) | 0 |

| Not answered | 1 (4) | 4 (12) |

| Religion: | ||

| Catholic | 8 (32) | 28 (85) |

| Christian | 8 (32) | 4 (12) |

| Jewish | 3 (12) | 0 |

| No affiliation | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Not answered | 5 (20) | 0 |

| Annual Income: | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 2 (8) | 15 (45) |

| $10.000–$19,999 | 3 (12) | 5 (15) |

| $20.000–$29,999 | 3 (12) | 1 (3) |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 4 (16) | 1 (3) |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 3 (12) | 0 |

| More than $50,000 | 8 (32) | 0 |

| No answer | 2 (8) | 11 (33) |

| Employment Status: | ||

| Employed for wages | 8 (32) | 6 (18) |

| Self-employed | 3 (12) | 3 (9) |

| Out of work and looking for work | 1 (4) | 2 (6) |

| Out of work but not currently looking | 2 (8) | 2 (6) |

| Homemaker | 1 (4) | 8 (24) |

| Unable to work | 3 (12) | 2 (6) |

| Retired | 6 (24) | 4 (12) |

| No answer | 1 (4) | 6 (18) |

Grounded theory methodology revealed several preliminary themes that were shared between the English speaking and Spanish-only speaking groups. These themes were: lack of knowledge regarding the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse, feelings of shame regarding their condition, difficulty in talking about their pelvic organ prolapse with others, fear related to symptoms of their pelvic organ prolapse, and emotional stress from coping with pelvic organ prolapse. Table 2 demonstrates these themes with representative quotes from the English and Spanish-only groups.

Table 2.

Focus Groups Preliminary Themes and Representative Quotes

| Preliminary Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| English Speaking Group | |

| Shame/Silence | |

| Lack of knowledge of the prevalence of POP | “I didn't know that it happened to women” |

| Embarrassed to speak with others | “It is not something you'd share with people because it is a humiliating thing” |

| Humiliation | “My OBGYN said, `Wow, no one would ever have mistaken the fact that you've had kids'…it was humiliating to me.” |

| Feeling like less of a woman, unnatural | “I feel like a freak of nature. This is so unattractive. This is so unsexy.” |

| Fear | |

| Cancer | “Maybe I have cancer because I am bleeding” |

| Infection | “Now that I have this prolapse, I get more infections” |

| Odor | “It smelled so bad as if it was rotting” |

| Discomfort | |

| Difficult to cope with POP | “I was just so uncomfortable with myself because I felt I had something there that doesn't belong” |

| Spanish Speaking Group | |

| Shame/Silence | |

| Lack of knowledge of the prevalence of POP | “I went to the bathroom and I felt myself and I didn't know what it was and I was scared” |

| Embarrassed to speak with others | “I wouldn't tell anyone because I was embarrassed” |

| Humiliation | “When you sit down there is a sound like air that happens and it's embarrassing. You feel horrible.” |

| Feeling like less of a woman, unnatural | “I had a disaster inside, my bladder, uterus, and intestines had fallen” |

| Fear | |

| Cancer | “I was scared for my children that this would be cancer” |

| Infection | “I got a cream but it wouldn't help and I got like an infection and itching” |

| Odor | “I felt something ugly like rotten. It was the odor.” |

| Discomfort | |

| Difficult to cope with POP | “There's a lot of depression, because your social life ends…everything ends” |

In the Spanish-only group there were two additional preliminary themes identified. These themes included fear related to surgery and concerns regarding the need to utilize an interpreter to communicate with physicians. This included less confidence in the doctor when an interpreter was used as well as concerns that the interpreters did not accurately translate what the patient was trying to communicate. Table 3 provides information from the Spanish-only groups on the preliminary themes with representative quotes.

Table 3.

Preliminary Themes Unique to Spanish Speaking Only Group

| Fear | |

| Surgery | “If I die in surgery, what will my children do?” |

| Communication Concerns | |

| Lack of confidence in doctors | “For me, I feel more trust if the doctor understands me directly without interpreter, I like it that way” |

| Lack of confidence in translators | “They (the interpreters) don't explain things well many times” |

Two concepts emerged from the data that was shared between the two groups related to pelvic organ prolapse.

Concept 1

Patients' lack of knowledge. This lack of knowledge included basic knowledge about anatomy and the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse. This resulted in patients' reported embarrassment regarding their condition, feelings of humiliation, and feeling somehow unnatural or less like a woman. This subsequently lead to the concept of shame and silence regarding their condition, including the feeling of self-blame for the development of the prolapse, such as “My mother would always caution me to not lift heavy things because later when you grow up, your insides will fall out”.

Concept 2

More information and education about pelvic organ prolapse is needed. The participants in the focus groups felt that more information and education about their condition would allow for more dialog with their families, healthcare providers and community. This information and dialog would help address their fears and difficulty coping with pelvic organ prolapse. Increased knowledge and dialog could also lead the way to relieve the humiliation and shame that women felt. The relief women felt in knowing they were not alone was clear: “You're not alone! And it doesn't have to be so private.” “I'm part of a big group of women here. It's not just me” In the Spanish-only group an addition unique concept emerged.

Concept 3

Spanish-only speaking women face additional communication challenges. Many women in the Spanish-only group expressed concerns about their communication with providers that didn't speak Spanish. They not only expressed concerns that they felt a lack of confidence in a provider that did not speak Spanish, they also frequently offered praise for the providers they had that did speak Spanish. Also disconcerting was the feeling that some women expressed that they not only felt uncomfortable in the presence of interpreters, but that they felt that the interpreters was not accurately translating what they said.

Discussion

In this study we found a common thread of shame and silence that women with pelvic organ prolapse experience. Women were surprised by the prevalence of POP, and their lack of knowledge about POP led to feelings of shame, inability to discuss it with others (silence), humiliation, fear and difficulty coping with the symptoms. These women felt strongly that more information and knowledge was needed and that in general there should be more dialog regarding this condition with the general public. Spanish-only speaking women had the additional burden of concerns that interpreters used by their providers were not accurately interpreting for them and that they felt less confident with providers who did not speak Spanish.

Other qualitative studies have found that urinary incontinence is associated with a negative impact on emotional well-being in men and women [15]. However, there is very little data on women's experience and expectations with pelvic organ prolapse. The majority of the literature focuses on goal achievement and expectations in women with prolapse planning treatment [8–10]. One qualitative study investigated experiences of women with prolapse planning surgery. In contrast to our findings, this study reported very few women had the experience of depression, lack of confidence or feeling less womanly because of their prolapse. However, this was in a population in the United Kingdom who was planning to undergo surgery, and did not report on ethnicity [8]. Previous work with our group found that the initial physician visit has a significant effect on patients' understanding of their pelvic floor condition(s). It was demonstrated that patient understanding of their treatment plan, even in the absence of complete understanding of their diagnosis, was helpful to increase control and reduce fears [16].

Another important finding of this study is the concerns that many Spanish-only speaking women had in regard to the use of interpreters. Prior work from our group has also found that there are many communication barriers for Latina women with pelvic floor disorders that contribute to a lack of understanding [17]. One of these barriers was the use of interpreters with limited knowledge of the appropriate vocabulary to discuss pelvic floor disorders and the use of non-credentialed interpreters. Other work has also found that when the healthcare professional is able to communicate directly with the patient in their language this contributes to a feeling of trust and confidence [18]. All sites in this study utilize trained, in-person interpreters, telephone interpreters and rarely, staff members. In general, sites do not use family members unless specifically requested to by the patient. However, women in the focus groups were discussing their past experiences with POP and these included interactions at other sites and with other providers. We were unable to capture the training or professionalism of the interpreters used in the past in these women's medical experiences. However, the mistrust expressed by the patients' must be further explored.

Strengths of this study include the inclusion of both English and Spanish speaking women with prolapse from geographically distinct areas and the use of the same trained bilingual moderator to conduct focus groups in English and Spanish. Also, the use of focus groups and qualitative analysis allows us to better explore how both English and Spanish speaking women experience pelvic organ prolapse and to identify concerns and problems that might otherwise be overlooked. Finally, women were recruited from a range of clinic settings and represented a wide range of socioeconomic status based on self-reported annual income. Weaknesses of this study include those inherent in qualitative studies such as the relatively small number of subjects. Also, this group of women was recruited from specialty clinics and may only represent women with more advanced prolapse. It is also possible that those subjects seeking care are inherently different and have different experience and concerns than women presenting to routine care or not seeking care. Finally, in the Spanish-only group, 70% of the women were from Mexico and therefore the results seen and concerns expressed by this group may not be generalizable to all Spanish-speaking women.

Future directions for this work include exploring ways to improve public awareness and knowledge of POP, especially the prevalence, symptoms, and causes with the goal of alleviating feelings of self-blame and providing reassurance that there are safe, effective treatments. There is a need for public awareness about pelvic floor disorders, specifically to reduce the shame and isolation women experience with pelvic organ prolapse. In particular, among Spanish-only speaking women more work is needed to explore how to help patients feel more comfortable with providers that don't speak Spanish and to improve trust in both providers and interpreters.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: Funded by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Act Award (1 K23DK080227, JTA) and an American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRAO Supplement (5K23DK080227, JTA), supported by a pilot grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at the University of New Mexico, National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant number UL1-RR031977.

DISCLOSURE: Rebecca G Rogers, MD is DSMB chair for the TRANSFORM trial sponsored by American Medical Systems

Appendix 1

Fig. A1.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION: G Dunivan: Data collection, Data Analysis, Manuscript writing

J Anger: Protocol/project development, Data Collection, Data analysis, Manuscript editing

A Alas: Data collection, Data Analysis, Manuscript editing

C Wieslander: Protocol/project development, Data Collection, Data analysis, Manuscript editing

C Sevilla: Protocol/project development, Data Collection, Data analysis, Manuscript editing

S Chu: Data Collection, Data analysis, Manuscript editing

S Maliski: Protocol/project development, Data analysis, Manuscript editing

B Barrera: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Manuscript editing

K Eiber: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Manuscript editing

R Roger: Protocol/project development, Manuscript editing

PRESENTATION INFORMATION: Poster presentation at the American Urogynecologic Society 33nd Annual Scientific Meeting in Chicago, IL. October 3–6th, 2012.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sung VW, Hampton BS. Epidemiology of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:421–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brincat CA, Larson KA, Fenner DE. Anterior vaginal wall prolapse: assessment and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:51–8. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cf2c5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudish BI, Iglesia CB. Posterior wall prolapse and repair. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:59–71. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cd41e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowder JL, Ghetti C, Moalli P, Zyczynski H, Cash TF. Body image in women before and after reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2010;21:919–25. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1455–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kammerer-Doak D. Assessment of sexual function in women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(Suppl 1):S45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0832-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L, Cartwright R. Experiences and expectations of women with urogenital prolapse: a quantitative and qualitative exploration. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1362–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawndy SS, Withagen MI, Kluivers KB, Vierhout ME. Between hope and fear: patient's expectations prior to pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(9):1159–63. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1448-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamik MM, Rogers RG, Qualls CR, Komesu YM. Goal attainment after treatment in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jun 13; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed 21 January 2013];Census Briefs Issued May 2011. 2010 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- 12.Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995–2050. U.S. Government Printing Office; [Accessed 31 January 2011]. 1996a. pp. 25–1130. at http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Subak LL. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;114(6):1271–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bf9cc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: an explication and interpretation. In: Emerson RM, editor. Contemporty Filed Research. Little Brown; Massachusetts: 1983. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teunissen D, Van Den Bosch W, Van Weel C, Lagro-Janssen T. “It can always happen”:the impact of urinary incontinence onelderly men and women. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24(3):166–73. doi: 10.1080/02813430600739371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiyosaki K, Ackerman AL, Histed S, Sevilla C, Eilber K, Maliski S, Rogers R, Anger J. Patients' understanding of pelvic floor disorders: what women want to know. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18(3):137–42. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318254f09c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan A, Sevilla C, Weislander C, Moran M, Rashid R, Mittal B, Maliski S, Rogers R, Anger J. Communication barriers among spanish-speaking women with pelvic floor disorders: lost in translation? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(3):157–64. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318288ac1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mutchler J, Bacigalupe G, Coppin A, Gottlieb A. Language barriers surrounding medicaiton use among older Latinos. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2007;22:101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]