Abstract

Primary cilia and their anchoring basal bodies are important regulators of a growing list of signaling pathways. Consequently, dysfunction in proteins associated with these structures results in perturbation of the development and function of a spectrum of tissue and cell types. Here, we review the role of cilia in mediating the development and function of the pancreas. We focus on ciliary regulation of major pathways involved in pancreatic development, including Shh, Wnt, TGF-β, Notch, and fibroblast growth factor. We also discuss pancreatic phenotypes associated with ciliary dysfunction, including pancreatic cysts and defects in glucose homeostasis, and explore the potential role of cilia in such defects.

Keywords: pancreas, cilia, ciliopathies, development, Shh, Wnt, TGF-beta, Notch, FGF, pancreatic cysts, glucose homeostasis

Introduction

The discovery of the role of primary cilia as cellular sensors mediating an expanding list of signaling pathways has begun to shed light onto the importance of this organelle in proper organogenesis and function. Recent evidence suggests, however, that although primary cilia are present on nearly every vertebrate cell type, their composition and function may vary in a tissue-specific and cell-specific manner (Gerdes et al., 2009; Ivliev et al., 2012). A comprehensive understanding of the role of cilia in coordination of cellular processes in each organ system is therefore necessary to fully understand their importance in human disease. Here, we discuss the role of cilia in the development and pathology of the pancreas. The pancreas, essential for the production of both digestive enzymes, as well as the production of glucose-regulating hormones, is a complex tissue with various cell types found in both exocrine and endocrine compartments. Pancreatic development is regulated by the interplay of several pathways, including sonic hedgehog (Shh), Wnt, TGF-β, Notch, and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), all of which have been linked to primary cilia. In this review, we provide an overview of the current understanding of pancreatic development under the control of these pathways, offering insight into the role of primary cilia. We also discuss pancreatic phenotypes associated with ciliopathies and ciliary mutant models, providing mechanistic insights into the link between disruption of cilia and pancreatic pathology.

Pancreatic Architecture and Development

The mature pancreas comprises exocrine and endocrine compartments consisting of various cell types, approximately 15% of which are ciliated (Table 1; (Kachar et al., 1979; Githens, 1988, 1994; Bonner-Weir, 2004). The exocrine tissue comprises approximately 99% of the organ and is composed of acinar and centroacinar cells arranged in glands that secrete digestive enzymes, including proteases, amylase, and lipase into the duodenum (Table 2). Ductal cells create a compartmentalized network consisting of the main duct and interlobular ducts connected to each other and to centroacinar cells, which link the network to acinar cells [(Reichert and Rustgi, 2011); reviewed in (Pan and Wright, 2011)]. Primary cilia have been identified on pancreatic ductal cells of the Chinese hamster, as well as centroacinar cells of the bat pancreas [(Boquist, 1968); D.W. Fawcett cited by (Sorokin, 1962)]. Interestingly, acinar cells are unique among exocrine cells, in that they are not ciliated (Cano et al., 2004; Ait-Lounis et al., 2007). The endocrine tissue, known as islets of Langerhans, is distributed throughout the organ and contains highly differentiated cell types including alpha (α), beta (β), delta (δ), epsilon (ε), and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) cells which are responsible for production and secretion of the hormones glucagon, insulin, somatostatin, ghrelin, and PP, respectively (Gittes, 2009; Pandol, 2011; Mansouri, 2012; Shih et al., 2013). In 1958, Munger (1958) first reported the presence of cilia on mouse pancreatic β-cells. These observations were later confirmed by electron microscopy in human β-cell tumor cells (Greider and Elliot, 1964). Primary cilia have since been reported on α- and δ-cells of several vertebrates, including adult rats, mice, and rabbits (Yamamoto and Kataoka, 1986; Aughsteen, 2001), although they are absent from PP-cells (Cano et al., 2004; Ait-Lounis et al., 2007). It is unknown if ε-cells are ciliated (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Ciliated Cell Types of the Developing Pancreas

| Pancreatic Cell Types | Function | Derived from: | Ciliated | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exocrine: | Pluripotent precursors within embryonic pancreatic epithelium | (Kim and Hebrok, 2001) | |||

| Acinar cell | Creates digestive enzymes called zymogens | Tip epithelium | No | (Cano et al., 2004; Hegyi and Petersen, 2013) | |

| Centroacinar cell | duct cell which connects secretory acini with intralobular ductal epithelium; secretes additional pancreatic digestive fluids | Dorsal and ventral buds | Yes | (Sorokin, 1962; Seeley et al., 2009; Cleveland et al., 2012) | |

| Duct cell | Produces a fluid that mixes with zymogens | Trunk epithelium, dorsal and ventral buds | Yes | (Aughsteen, 2001; Zhang et al., 2005; Hegyi and Petersen, 2013) | |

| Endocrine: | Endocrine-biased progenitors found in the trunk epithelial | (Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Pan and Wright, 2011) | |||

| Alpha-cell | Secretes the hormone glucagon | Dorsal (early) and ventral buds | Yes | (Hellman et al., 1962; Greider and Elliot, 1964; Yamamoto and Kataoka, 1986; Aughsteen, 2001; Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Zhang et al., 2005; Seeley et al., 2009) | |

| Beta-cell | Produces insulin and islet cell amyloid polypeptide (amylin) | Dorsal and ventral buds | Yes | (Lacy, 1957; Like, 1967; Yamamoto and Kataoka, 1986; Aughsteen, 2001; Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Zhang et al., 2005) | |

| Delta-cell | Secretes the hormone somatostatin and vasoactive intestinal peptide | Dorsal and ventral buds | Yes | (Yamamoto and Kataoka, 1986; Aughsteen, 2001; Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Zhang et al., 2005) | |

| PP (gamma, F)-cell | Secretes pancreatic polypeptide | Ventral pancreatic bud | No | (Larsson et al., 1974; Larsson et al., 1975; Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Ait-Lounis et al., 2007) | |

| Epsilon-cell | Secretes the hormone ghrelin | Dorsal and ventral buds | Unknown | (Andralojc et al., 2009) | |

| Enterochromaffin cells | Secretes serotonin, motilin, substance P, histamine and kinins | Unknown, but located in head (dorsal) | Unknown | (Buffa et al., 1977; Cetin, 1988; Wierup et al., 2013) | |

| G-cell | Secretes gastrin | Unknown | Unknown | (Wierup et al., 2013) | |

| C-cell | No known function | Unknown | Unknown | (McClish and Eglitis, 1969) | |

TABLE 2.

Pancreatic Developmental Cellular Composition

| Cellular population composition during development | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic cell types | Mid-gestational fetal cell population | Newborn cell population | Mature pancreas cell population | |||||

| Exocrine: | Total: 80% | Total: 93–94% Duct: 50–60% |

Total: 80%a Duct: 10–14% |

|||||

| Reference: | (Bouwens and Rooman, 2005) | (Kachar et al., 1979; Rahier et al., 1981) | (Kachar et al., 1979; Githens, 1988, 1994; Bonal and Herrera, 2008) | |||||

| Endocrine: | Total: 20% | Total: 6–7% | Total: 1% | |||||

| Reference: | (Bouwens and Rooman, 2005) | (Rahier et al., 1981) | (Malaisse, 2005) | |||||

| Rat | Human | Rat | Baboon | Rat | Human | |||

| Reference: | (Wierup et al., 2002; Steiner et al., 2010) | (Stefan et al., 1983; Wierup et al., 2002; Bonner-Weir, 2004; Jeon et al., 2009; Andralojc et al., 2009; Steiner et al., 2010) | (Wierup et al., 2002) | (Wolfe-Coote et al., 1988; Steiner et al., 2010; Quinn et al., 2012) | (Elayat et al., 1995; Steiner et al., 2010) | (Stefan et al., 1983; Bonner-Weir, 2004; Cleaver and Melton, 2004; Andralojc et al., 2009; Steiner et al., 2010) | ||

| Alpha-cell | 36 ±5.3% | Few cells to 33% | 34% | 16% | 15–20% | 15–20% | ||

| Beta-cell | 31 ±4.4% | 34.0 ±3.8% | 31% | 14% | 65–80% | 70–80% | ||

| Delta-cell | 23 ±8.5% | 39.2 ±11.1% | 23% | 15% | 3–10% | 5–10% | ||

| PP (gamma, F)-cell | 1 ±0.5% | 42.6 ±4.0% | 1% | Present, but % unknown | 3–5% | <1% | ||

| Epsilon-cell | 9 ±2.3% | 14.8 ±10.2% | 11% | 5% (human) | <1% | 1% | ||

| Enterochromaffin cells | <1% | |||||||

| G-cell | <1% | |||||||

| C-cell | <1% | |||||||

Blood vessels, lymphatics, nerves, and excretory ducts constitute about 18% of the pancreas (Barth and Burdick, 2010).

DEVELOPMENT OF THE PANCREAS

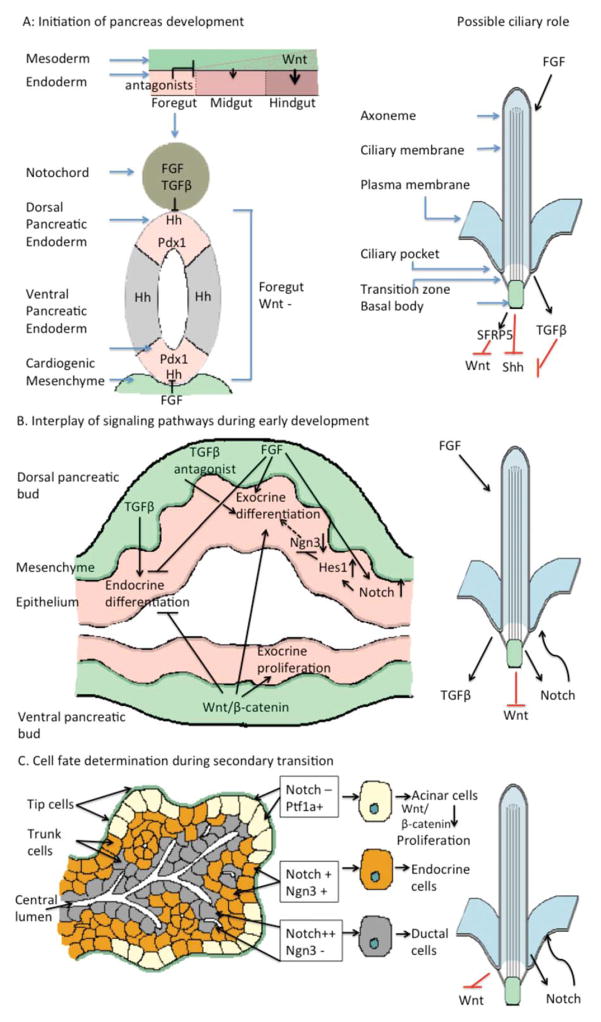

Pancreatic development begins early in embryogenesis, and is comprised of three major developmental processes: (1) formation and patterning of the endoderm, (2) specification of the pancreatic primordium, and (3) differentiation of exocrine and endocrine cell types. Patterning of the endoderm is initiated primarily through anterior–posterior (A–P) regionalization of the gut tube by concentration gradients of high FGF expression derived from the surrounding mesoderm and low levels of canonical Wnt signaling in the anterior endoderm, allowing for subsequent foregut specification (Kikuchi et al., 2000; Stafford and Prince, 2002; Jørgensen et al., 2007). FGF and TGF-β signaling from the notochord suppress expression of sonic hedgehog (Shh) in the presumptive dorsal pancreatic epithelium, resulting in dorsal pancreatic bud formation (Jørgensen et al., 2007) and a similar process occurs in the ventral pancreatic epithelium. The pancreatic buds are comprised of pancreatic progenitor cells expressing Pdx1, the broad pancreatic marker, as well as Ptf1a, an important regulator of progenitor cell proliferation and acinar cell differentiation (Gu et al., 2002; Burlison et al., 2008). The fusing of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds is followed by transition from the highly proliferative progenitor cell state to differentiation of exocrine and endocrine cell types, which marks the maturation of the pancreas. Those cells closest to the extracellular matrix, known as tip cells, are highest in exposure to mesenchymal FGF and acquire an acinar cell fate with activation of Wnt, Notch and Ptf1a, as well as downregulation of progenitor cell-maintaining factors. Cells within the trunk commit to either ductal or endocrine fates. These events are mediated by complex regulation of production and detection of signaling molecules. Although comprehensive reviews of pancreatic development have been presented elsewhere (Kim and Hebrok, 2001; Grapin-Botton, 2008; Gittes, 2009; Tiso et al., 2009; Zorn and Wells, 2009; Pan and Wright, 2011; Pandol, 2011; Mansouri, 2012; Hegyi and Petersen, 2013; Shih et al., 2013), this discussion will focus on the role of cilia in these events through pathway regulation (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Regulation of pancreatic development by cilia-dependent pathways. A. In early endodermal patterning, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is excluded from the foregut endoderm by foregut expression of antagonists (McLin et al., 2007). The dorsal and ventral pancreatic endoderm of the foregut are subsequently specified by suppression of Shh signaling, as a result of FGF and TGF-β signaling from the notochord (Hebrok et al., 1998) and FGF signaling from the cardiogenic mesenchyme (Deutsch et al., 2001). Expression of the pancreatic progenitor marker Pdx1 is upregulated throughout the pancreatic endoderm, specifying progenitor cells that will contribute to the mature organ. Primary cilia prevent improper activation of both canonical Wnt signaling (Gerdes et al., 2007; Corbit et al., 2008), as well as Shh (Cervantes et al., 2010), and are required for proper TGF-β signaling (Clement et al., 2013), implicating proper ciliary function in the patterning of the gut endoderm and the specification of pancreatic progenitor cells. In addition, FGF signaling regulates the length of primary cilia (Brody et al., 2000; Bonnafe et al., 2004; Urban et al., 2006; Neugebauer et al., 2009), which blocks inappropriate activation of Hh signaling in pancreatic epithelium (Cervantes et al., 2010), suggesting that FGFs may repress Hh in pancreatic endoderm by maintaining cilia. B. The pancreatic epithelium, defined by Pdx1 expression, evaginate to form dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds. Pdx1+ cells that lack Notch signaling transiently express Ngn3 and eventually give rise to endocrine cells. Those that retain Notch signaling express Ptf1a, repress Ngn3 expression, and give rise to exocrine cells (Gu et al., 2002; Herrera et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2003). Notch signaling is maintained by mesenchymal FGFs (Hart et al., 2003; Norgaard et al., 2003; Miralles et al., 2006), which favors exocrine differentiation over endocrine differentiation (Bhushan et al., 2001; Hart et al., 2003; Norgaard et al., 2003; Jacquemin et al., 2006). Canonical Wnt signaling is required for the proliferation of pancreatic progenitor cells (Dessimoz et al., 2005; Murtaugh et al., 2005; Papadopoulou and Edlund, 2005; Heiser et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2007), as well as for the exocrine acinar cells (Murtaugh et al., 2005; Wells et al., 2007). Primary cilia in the pancreas are necessary to preclude overactivation of Notch signaling, and therefore may regulate the balance between endocrine and exocrine fates (Cervantes et al., 2010). TGF-β signaling from the surrounding mesenchyme is also important to drive production of endocrine fates from the pancreatic epithelium and inhibit exocrine fates. In contrast, canonical Wnt signaling is essential for the proliferation of acinar cells and preventing endocrine differentiation. Given the role of cilia in inhibiting Wnt signaling and promoting TGF-β signaling, cilia may block improper Wnt signaling and promote TGF-β in endocrine precursor cells. The absence of cilia in the main exocrine lineage, acinar cells, however, may serve the opposite function, providing an environment conducive to high levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. C. During the secondary transition of pancreatic development, tip cells at the termini of ducts give rise to exocrine acinar cells and trunk cells lining the ducts give rise to endocrine and ductal cells. Notch signaling regulates the balance between tip and trunk fates; active Notch promotes trunk identity and represses tip identity, and tip cells expressing low levels of Notch proliferate rapidly under the control of canonical Wnt signaling, ultimately producing acinar cells. Additionally, trunk cells maintain dual potential: high levels of Notch activity lead to the formation of duct cells through repression of Ngn3 and low levels of Notch enhance Ngn3 expression, driving differentiation of endocrine cells (Shih et al., 2012). Primary cilia may regulate these processes by coordinating regulation of Notch.

CILIARY REGULATION OF SIGNALING IN PANCREATIC DEVELOPMENT

Sonic hedgehog (Shh)

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) is a secreted protein of the Hedgehog (Hh) family of ligands which, upon binding to their receptor Patched (PTCH), relieve its inhibition of Smoothened (SMO). Active SMO converts the Gli proteins from transcriptional repressors to transcriptional activators, driving expression of target genes (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980; Ruppert et al., 1988; Hui et al., 1994; Marigo et al., 1996; AzaBlanc et al., 1997; Goodrich et al., 1997; Altaba, 1999; Sasaki et al., 1999; Schweitzer et al., 2000; Ingham and McMahon, 2001; McMahon et al., 2003; Ingham, 2008). Primary cilia are essential for proper Shh signaling in vertebrates. In the absence of ligand, PTCH1 is located at the base of the cilium and prevents ciliary entry of SMO (Corbit et al., 2005; Rohatgi et al., 2007). On ligand binding, PTCH1 exits the cilium, allowing SMO translocation to the ciliary membrane. The Gli transcription factors are also present in cilia, and their accumulation at the ciliary tip increases upon SMO activation correlating with transcriptional activation of Shh targets (Haycraft et al., 2005; Endoh-Yamagami et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009b).

In the mouse embryo, Shh is expressed throughout the embryonic gut endoderm (Echelard et al., 1993; Bitgood and McMahon, 1995; Ramalho-Santos et al., 2000), but is exclusively excluded from the pancreatic bud endoderm, which expresses high levels of the pancreatic progenitor marker, Pdx1 (Apelqvist et al., 1997; Hebrok et al., 1998; Hebrok et al., 2000). The repression of Shh in the dorsal pancreatic bud endoderm is mediated by notochord-derived signals, namely the TGF-β family member, activin-βB, and FGFs (Kim et al., 1997a; Hebrok et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2000). Shh signaling in ventral pancreatic endoderm is suppressed by FGF from the cardiogenic mesenchyme (Deutsch et al., 2001). In mouse and chick, ectopic expression of Shh in embryonic pancreatic epithelium results in loss of Pdx1 expression and subsequent transformation of pancreatic mesenchyme into gut mesoderm. Pancreatic endocrine and exocrine cells, however, develop but are mislocalized to the intestinal wall (Apelqvist et al., 1997; Hebrok et al., 1998). Similarly, while loss of Shh signaling does not impede development of the pancreas, it results in overproduction of endocrine cell types (Kim et al., 1997b; Hebrok et al., 2000). In human, Hh signaling components have been identified in the primary cilia of developing pancreatic duct cells. Hh signaling is also low during early pancreatic development, as human ductal cilia are devoid of Hh effectors, SMO and GLI2, at embryonic week 7.5. Both SMO and GLI2 gradually begin to accumulate in primary cilia at later stages between embryonic weeks 14 and 18 (Nielsen et al., 2008). Moreover, the presence of GLI3, whose expression is repressed by Hh signaling (Marigo et al., 1996; Buscher and Ruther, 1998; Schweitzer et al., 2000), is reduced gradually during pancreas development in the nucleus and cytoplasm of ductal epithelial cells (Nielsen et al., 2008), supporting the concept that in mammals, Hh signaling is repressed in early pancreatic progenitors and is required for both proliferation and maturation of the pancreas during later stages of development.

Given the central role of primary cilia in regulation of Shh, they have been implicated in key aspects of pancreatic development. Evidence suggests that primary cilia in pancreatic epithelium cells may block inappropriate activation of Hh signaling by regulating the GLI transcription factors (Cervantes et al., 2010). Overexpression of constitutively active GLI2 in transgenic mice [Pdx1-Cre;CLEG2 (di Magliano et al., 2006)] failed to completely activate the pathway in the pancreatic epithelium. Compounded with the loss of cilia in Pdx1-Cre;CLEG2;Kif3alox/lox, Ptch1lacZ/+ mice, however, the pathway was aberrantly activated, suggesting that the presence of primary cilia is necessary for impeding improper Hh activation in pancreas (Cervantes et al., 2010). Importantly, this regulation was downstream of Ptch1 and Smo, as elimination of cilia along with either did not significantly disrupt activation. The activation of Hh in this context did significantly disrupt pancreatic morphogenesis in 2–3 week old mice with a loss of differentiated exocrine cell types, primarily acinar cells, and an expansion of abnormal duct-like epithelial cells expressing markers of undifferentiated progenitor cells (Cervantes et al., 2010). Endocrine cell loss was also observed in these animals, likely due to postnatal cell death, suggesting the importance of primary cilia in maintaining reduced levels of Hh activation to allow differentiation of mature cell types (Cervantes et al., 2010).

The possibility that loss of cilia leads to loss of differentiation was supported by the observation that primary cilia-driven ectopic activation of Hh signaling in adult β-cells of Pdx1-CreER;CLEG2;Kif3af/f mice resulted in decreased insulin expression and secretion, as well as defects in glucose sensing (Landsman et al., 2011). This loss of β-cell functionality was due to their dedifferentiation. Further, the persistent Hh signaling ultimately transformed those cells to undifferentiated pancreatic tumors (Landsman et al., 2011). This finding was consistent with reports that elevated Hh signaling in cilia results in tumorigenesis. Cancer cells in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are devoid of cilia (Bailey et al., 2009; Seeley et al., 2009). Furthermore, these cells exhibit active Shh signaling and lack SMO, in contrast with the surrounding ciliated stromal cells, which was likely responsible for driving tumorigenesis as well as metastasis (Bailey et al., 2009). Consistent with this, cultured human PDAC cell lines, CFPAC-1 and PANC-1, are largely lacking in cilia, but those that are present exhibit less PTCH1 and very high levels of SMO, even in the absence of a Hh ligand (Nielsen et al., 2008). This suggests that either a lack of cilia or perhaps perturbed ciliary function results in activation of Hh signaling in the cancerous cell lines, and underscores the possibility that proper ciliary regulation of the pathway is required for maintenance of differentiated pancreatic cell fates.

Wnt

Wnt signaling molecules are secreted proteins that bind to Frizzled (Fz) transmembrane receptors and LRP5/ 6 coreceptors (Bhanot et al., 1996; YangSnyder et al., 1996; Hsieh et al., 1999; Tamai et al., 2000; Umbhauer et al., 2000; Mao et al., 2001). The canonical pathway is characterized by recruitment of disheveled (Dsh) to the plasma membrane on Wnt binding, resulting in the cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin and its subsequent translocation to nucleus, where it directs target transcription in coordination with TCF/LEF (T cell-specific factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor) transcription factors (Kioussi et al., 2002; Baek et al., 2003). In the absence of Wnt, β-catenin is phosphorylated and is degraded via proteasomes (He et al., 2004; Logan and Nusse, 2004). Studies suggest the presence of unphosphorylated β-catenin in cilia and phosphorylated β-catenin at the basal body (Corbit et al., 2008). In the absence of Wnt ligands, elevated levels of β-catenin have been observed in cells and organisms deficient in ciliary proteins, including KIF3A and BBS4, potentially through a direct interaction of BBS4 with the proteasomal subunit RPN10, as well as a spatial relationship between proteasomes and this region of the cell (Wigley et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2003; Gerdes et al., 2007; Corbit et al., 2008). In addition, evidence suggests that the ciliary protein, inversin, is required for inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling by targeting Dsh for degradation (Simons et al., 2005). The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is therefore likely dependent on cilia for proper degradation of β-catenin and inhibiting aberrant activation.

During development of the pancreas, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is critical from the earliest stages of endoderm patterning through differentiation of exocrine and endocrine cell types [reviewed in (Murtaugh, 2008)]. Initially, suppression of pathway expression is necessary in the anterior endoderm to maintain foregut identity (McLin et al., 2007). Consistent with this inhibitory role, ectopic Wnt/β-catenin signaling during early pancreas development leads to complete pancreas agenesis in mice (Heller et al., 2002; Heiser et al., 2006). Wnt antagonists secreted from foregut endoderm repress the pathway in this region (Pilcher and Krieg, 2002; Li et al., 2008). This may be at least partially regulated by cilia, as expression of one Wnt antagonist, Sfrp5, is regulated by cilia. Depletion of cilia in Ift88fl/fl mice decreased Sfrp5 expression with a concomitant upregulation of Wnt signaling and loss of srfp5 in zebrafish produced defects in endoderm-derived organogenesis, including impaired production of islets (Chang and Serra, 2013; Stuckenholz et al., 2013). After endodermal patterning, Wnt likely plays an inhibitory role in the pancreatic epithelium. Transgenic expression of a stabilized form of β-catenin in mice at around E10.5, when the buds emerge, leads to pancreas agenesis as a result of downregulation of FGF10 expression, upregulation of Shh signaling, and subsequent loss of Pdx1 expression (Heiser et al., 2006). In contrast, after the formation of pancreatic buds, Wnt is essential for proliferation of pancreatic progenitor cells, as well as for proliferation of newly specified acinar cells (Dessimoz et al., 2005; Murtaugh et al., 2005; Papadopoulou and Edlund, 2005; Heiser et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2007). This proliferative role is supported by the resulting pancreatic hypoplasia, largely affecting exocrine cells with some effects on islets when β-catenin signaling is perturbed in Pdx1-expressing progenitors (Murtaugh et al., 2005; Papadopoulou and Edlund, 2005; Wells et al., 2007). Consistently, activated β-catenin prevents endocrine differentiation in chick (Pedersen and Heller, 2005), further supporting the proliferative role of the canonical Wnt pathway during the latter part of pancreatic specification.

Though it remains to be elucidated how ciliary regulation of Wnt signaling may contribute to regulation of the developing pancreas, there is evidence of deregulated Wnt signaling in pancreatic cells lacking normal cilia. The developing pancreatic epithelium of the Ift88 mutant oak ridge polycystic kidney (orpk) mouse was mostly devoid of cilia and the remaining cilia were smaller than normal (Cano et al., 2004). Further, the newborn orpk pancreas is characterized by acinar cell apoptosis, as well as ductal hyperplasia. Interestingly, pancreatic cells of orpk mice exhibited increased cytosolic β-catenin and transcription of TCF/LEF targets, suggesting the role of cilia in mediating levels of pancreatic Wnt signaling (Cano et al., 2004). In light of the importance of β-catenin signaling in mediating the balance between proliferation and differentiation in pancreatic cell types, these findings implicate the cilium in monitoring the levels of Wnt transduction to control that balance. Moreover, given that pancreatic development is marked by an absence of Wnt signaling in the ciliated endoderm and active Wnt in the proliferation of nonciliated acinar cells, cilia may serve to inhibit aberrant proliferation and drive differentiation.

TGF-β

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling is driven by binding of secreted growth factors of the TGF-β superfamily to transmembrane serine/threonine kinase type I and type II receptors. Ligand binding results in tetramerization of two of each type of receptor and the subsequent phosphorylation and activation of the receptor I kinase domain by receptor II. The activated receptor phosphorylates receptor-regulated Smad (R-Smad) proteins which complex with comediator Smad (Co-Smad) proteins. The complex translocates to the nucleus where it mediates transcription of target genes. Inhibitory Smad (I-Smad) proteins negatively regulate the pathway by competitively binding to activated receptor or Co-Smad, I-Smad, or by targeting the receptor for degradation (Shi and Massague, 2003). In addition, TGF-β receptors can be regulated by clathrin-dependent endocytosis in vesicles enriched in SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA), which recruits R-Smad for activation (Tang et al., 2010; Huang and Chen, 2012).

TGF-β ligands are expressed in various regions of the developing pancreas, including the pancreatic epithelium, the surrounding mesenchyme, and both developing and mature islets (Ogawa et al., 1993; Feijen et al., 1994; Furukawa et al., 1995; Verschueren et al., 1995; Crisera et al., 1999; Tremblay et al., 2000; Dichmann et al., 2003). At early stages, the TGF-β superfamily protein, Activin-B, is secreted from the notochord, binds to ActR receptors in pancreatic endoderm, and represses expression of Shh in the foregut epithelium, promoting the specification of pancreatic progenitors (Kim and Hebrok, 2001; Kim and MacDonald, 2002; Johansson and Grapin-Botton, 2002; Hebrok, 2003). ActR receptors are also expressed in the islets (Yamaoka et al., 1998; Shiozaki et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2000; Goto et al., 2007). The ActR ligand Activin-B is also expressed in the glucagon positive α-cells during early mouse development (E12.5) and later (E18.5) in differentiated islets (Maldonado et al., 2000), suggesting a role of Activin signaling in lineage specification (Ritvos et al., 1995). It is therefore not surprising that mutations in ActR or its mediator, Smad2, result in reduced islet in mice (Yamaoka et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2000; Goto et al., 2007) or that overexpression of Smad7, an inhibitor of the pathway, also leads to reduction in β-cell mass (Smart et al., 2006). Likewise, another TGF-β inhibitor, follistatin, which is expressed in the mesenchyme during early developmental stages (before E12.5) and in differentiated islets at E18.5, inhibits endocrine differentiation while also promoting the specification of exocrine tissue (Miralles et al., 1998). These findings suggest a role for TGF-β signaling in driving endocrine tissue production, while inhibiting exocrine fates. However, another TGF-β ligand, GDF11, may actually inhibit endocrine development (Harmon et al., 2004). Therefore, although the complete role of various TGF-β ligands and receptors in achieving the balance between exocrine and endocrine fates remains to be elucidated, the pathway is clearly integral to both early and late stages of pancreatic development.

Recent evidence has implicated primary cilia in the regulation of TGF-β signaling, suggesting that the cilium may serve as an intracellular site in which signaling components are brought together. The ciliary pocket region is a unique site for endocytosis; both early endosomes and clathrin-dependent endocytic vesicles are enriched in this region (Poole et al., 1985; Molla-Herman et al., 2010; Rattner et al., 2010; Ghossoub et al., 2011). As such, the fact that TGF-β receptor internalization via clathrin-coated pits enhances the signaling by sequestering the receptors and R-Smads (Tang et al., 2010; Huang and Chen, 2012) suggests a possible role for cilia in regulation of the signaling components. Indeed, TGF-β RI and TGF-β RII are located at the ciliary tip and, on activation, are trafficked to the base of the cilium where they activate Smad2/3 (Clement et al., 2013). Smad4, which is also located at the ciliary base, complexes with phosphorylated Smad2/3 and translocates to nucleus (Clement et al., 2013). This process is dependent on the presence of a cilium, as embryonic fibroblasts of the orpk mouse, which exhibit shorter cilia (Schneider et al., 2005; Corbit et al., 2008), express similar levels of TGF-β RI and TGF-β RII, but reduced clathrin dependent endocytosis and reduced localization of the receptors and pSmad2/3 at the base of cilium, correlating with a reduction in pathway activation (Clement et al., 2013). While this implicates a dependence on cilia for proper TGF-β signaling, its role in pancreatic development remains unclear. Pancreatic architecture in the orpk mouse begins to be disrupted late in gestation, but is primarily characterized by loss of exocrine cell types with no effect on islets (Cano et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005), consistent with a possible role for the pathway in maintaining the balance between both compartments. Given the multiple roles of TGF-β at both early and late stages of pancreatic development, it will be necessary to investigate perturbation of cilia at discrete developmental time points to delineate their role in mediating TGF-β regulation of pancreatic phenotypes.

Notch

Transmembrane Notch receptors are bound and activated by ligands of the delta Jagged family proteins present on the surface of neighboring cells. Binding results in sequential proteolytic cleavages of the receptor, which ultimately produces a Notch intracellular domain (NICD) fragment that translocates to the nucleus to drive transcription of target genes (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1999; Radtke and Raj, 2003; Schweisguth, 2004). Notch receptors are expressed in pancreatic epithelium as well as mesenchymal and endothelial cells (Lammert et al., 2000), and signaling suppresses differentiation and induces proliferation in pancreatic progenitors (Ahnfelt-Ronne et al., 2007; Fujikura et al., 2007). Similarly, in mouse, this balance is dictated by expression of HES genes under the control of nuclear NICD bound to the DNA-binding protein, RBP-Jκ, which inhibit expression of Ngn transcription factors (Lewis, 1996; Ma et al., 1996; Sommer et al., 1996; Beatus and Lendahl, 1998). Ngn3, in particular, is expressed in the pancreatic progenitor cells and commits them to endocrine fates (Gu et al., 2002; Herrera et al., 2002). Notch, therefore, promotes exocrine fates by enhancing expression of its target, Hes1, which at the same time inhibits endocrine differentiation via suppression of Ngn3 during early pancreas development (Jensen et al., 2000). Consistently, loss of Notch signaling in early pancreatic development results in precocious differentiation of endocrine cells at the expense of ductal cells (Jensen et al., 2000; Parsons et al., 2009). Although the detailed mechanism is unclear, it has been suggested that Ngn3 may direct expression of the Notch ligand, Dll1, resulting in NICD-dependent transcription of Hes1 in neighboring cells which, in turn, inhibits Ngn3 and promotes the exocrine fate (Gasa et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2010). Later, after the establishment of Ngn3+ progenitor cells, Notch signaling is important for differentiation of endocrine fates (Cras-Meneur et al., 2009). The level of Notch signaling also determines the ductal or endocrine fate of trunk cells by regulating both positive (Sox9) and negative (Hes1) regulators of Ngn3 (Shih et al., 2012). High Notch signaling results in the expression of both Hes1 and Sox9, and gives rise to a ductal lineage. By contrast, low levels of Notch results in the expression of only Sox9 and differentiation of endocrine cells (Shih et al., 2012).

Ciliary regulation of Notch signaling is not well understood and appears to be tissue-dependent. Discrepant effects on Notch have been reported with ablation of cilia in the pancreas and other tissues, namely developing skin epithelium. Deletion of Kif3a in the suprabasal cells in embryonic mouse skin impedes Notch signaling, resulting in defective skin development (Ezratty et al., 2011). In these cells, the Notch3 receptor localizes to the cilium and, Presenilin-2, the γ-secretase component catalyzing NICD cleavage, localizes to the basal body, indicating a direct dependence of Notch on the primary cilium. By contrast, depletion of cilia in developing pancreas via elimination of Kif3a gene in a transgenic mouse model (Pdx1-Cre; CLEG2; Kif3alox/lox, Ptch1lacZ/+) resulted in the upregulation of Notch pathway with an increase in Hes1 expression (Cervantes et al., 2010). While these discrepant findings suggest the likelihood of tissue- and stage-dependent ciliary regulation of Notch, the finding that loss of cilia results in increased signaling in the pancreas (Cervantes et al., 2010) suggests that, similar to Shh and Wnt signaling, proper ciliary function is necessary to maintain Notch signaling below a certain threshold of activation. Indeed, loss of ciliopathy proteins results in increased activation of the pathway in zebrafish embryos and multiple cell lines (Leitch et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014). This would be consistent with the perturbation of exocrine fates in the absence of cilia, without major consequences for endocrine cells (Cano et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). In addition to ciliary regulation of Notch, Notch also regulates formation of cilia and ciliary length. For example, Notch regulates the length of cilia in Kupffer’s vesicle in association with ligand DeltaD in zebrafish. Shorter cilia are produced in the absence of Notch signaling and hyperactive signaling leads to longer cilia (Lopes et al., 2010). In the pancreas, the Notch target genes, Sox9 and Tcf2, control ciliogenesis (Gresh et al., 2004; Zong et al., 2009; Shih et al., 2012). Interestingly, Sox9-deficient mice exhibit decreased Pkd2 expression, reduced number of cilia in the pancreatic epithelium, and ductal lumen as well as development of pancreatic cysts (Shih et al., 2012). Given that loss of Tcf2 leads to formation of cysts in the kidney (Gresh et al., 2004), this Notch effector may play a similar role in mediating ciliogenesis in the pancreas. Although this intricate mechanism of feedback is yet to be clearly established, evidence suggests that cilia regulate the level of Notch in the developing pancreas and that Notch in turn regulates primary cilia, maintaining a proper threshold of signaling.

FGF

FGFs are extracellular ligands that bind to the extracellular domain of FGF receptors (FGFRs), a family of tyrosine kinase receptors, in combination with heparan sulphate. Binding of two FGF molecules along with one or two heparan sulfate proteoglycans results in receptor dimerization, which leads to conformational changes and cross phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain of the receptors. This triggers several different signaling pathways, such as, the Ras/ERK pathway, the Akt pathway, and the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway (Schlessinger, 2000; Dailey et al., 2005; Mohammadi et al., 2005).

Secreted from the surrounding mesenchyme, FGFs are critical regulators of the pancreatic epithelium proliferation and differentiation. FGFs secreted from notochord and cardiogenic mesenchyme suppress Shh signaling in dorsal and ventral pancreatic endoderm, respectively (Kim et al., 1997a; Hebrok et al., 1998; Deutsch et al., 2001). Pdx1 expression in pancreatic progenitors is initiated by Fgf2 and Fgf10 in mice (Le Bras et al., 1998; Bhushan et al., 2001). The default programming of epithelium in the absence of mesenchymal signals is toward islets, but the mesenchymal interaction leads to exocrine differentiation (Gittes et al., 1996; Miralles et al., 1998). FGF7, for example, binds to FGFR2IIIb, activating proliferation in the pancreatic epithelium, and repressing endocrine differentiation (Zhang et al., 2006). Removal of Fgf7 results in differentiation of endocrine cells (Elghazi et al., 2002). Similarly, Fgf10, a high affinity ligand for FGFR2b, is highly expressed in the mesenchyme surrounding the pancreatic buds during the early stages of development (Bhushan et al., 2001), with decreased expression in the pancreatic epithelium at later developmental stages (Hart et al., 2003). Persistent expression of Fgf10 in the developing pancreatic epithelium of transgenic mice leads to pancreatic hyperplasia as a result of increased proliferation of pancreatic epithelial cells and perturbed differentiation of endocrine cells (Hart et al., 2003). Likewise, mice lacking FGFR2b signaling, due to lack of FGFR2b or FGF10 develop pancreatic hypoplasia (Celli et al., 1998; Ohuchi et al., 2000; Bhushan et al., 2001; Revest et al., 2001). FGF10 promotes pancreatic progenitor proliferation by inducing Pdx1 expression and maintaining Ptf1a expression; these cells fail to proliferate in the absence of FGF10 (Bhushan et al., 2001; Hart et al., 2003; Norgaard et al., 2003; Jacquemin et al., 2006). Although the role of FGF signaling in mediating early proliferative and progenitor capacity is critical, the downstream cascade by which this occurs is not completely understood.

One possible mechanism by which FGF participates in pancreatic specification is through its regulation of ciliogenesis. FGF regulates the length of primary cilia and, therefore, ciliary function. In zebrafish, Fgf8 and Fgf24 activate Fgfr1 and regulate the expression of foxj1 and rfx2, transcription factors known to play significant roles in ciliogenesis (Brody et al., 2000; Bonnafe et al., 2004; Neugebauer et al., 2009). These factors activate intraflagellar transport genes such as ift88 (Neugebauer et al., 2009). Consistently, suppression of Fgfr1 in zebrafish leads to reduced ciliary length in Kupffer’s vesicle (Neugebauer et al., 2009), as does suppression of FGF8 and downstream effectors, ler2 and fibp1 (Hong and Dawid, 2009). Therefore, it is possible that FGF signaling is necessary for proper production of the cilium, which coordinates the intricate balance of pathways required for proper pancreatic development. For example, FGF10 maintains Notch signaling and Hes1 expression in developing pancreas (Hart et al., 2003; Norgaard et al., 2003; Miralles et al., 2006), and sustained expression of Fgf10 in transgenic mice inhibits Ngn3 expression within pancreatic epithelium as a result of active Notch, ultimately impeding pancreatic cell differentiation (Hart et al., 2003). Therefore, Notch signaling acts as a downstream mediator of FGF10 signaling in pancreatic precursor cells (Miralles et al., 2006), potentially through primary cilia. Similarly, FGF is necessary for proper regulation of other pathways, including Shh and Wnt signaling. In light of the important role of cilia in regulation of these pathways, it is possible that FGF mediates the availability of cilia to regulate them, a possibility that remains to be explored.

PANCREATIC PHENOTYPES ASSOCIATED WITH CILIARY DYSFUNCTION

Defects in cilia have been associated with a spectrum of human diseases collectively called ciliopathies (Badano et al., 2006). While each clinical entity is characterized by discrete genetic mutations and phenotypes, overlap in both is prevalent across the diseases. These include renal cysts, retinal degeneration, laterality defects, and polydactyly (Beales and Kenny, 2014). Defects of the pancreas, however, have been less well-characterized, although they have been described in many ciliopathies. Dysplasia and fibrosis of the pancreas and liver have been reported in patients harboring mutations in genes associated with nephronopthisis (NPH), including mutations in NEK8/NPHP9 and NPHP3 (Bergmann et al., 2008; Frank et al., 2013). Fibrocystic disease of the pancreas has also been reported in oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 (OFD1), Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, and renal–hepatic–pancreatic dypslasia (Bernstein et al., 1987; Yerian et al., 2003; Chetty-John et al., 2010; Ware et al., 2011). The more prominent pancreatic feature of ciliopathies is the presence of ductal cysts. Pancreatic cysts have been reported in about 10% of patients diagnosed with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), the most common ciliopathy (Fick et al., 1995; Torra et al., 1997; Nicolau et al., 2000; Igarashi and Somlo, 2002). In contrast, about 70% of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), an atypical ciliopathy and inherited tumor syndrome caused by mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene, exhibit pancreatic cysts of varying severity, including simple cysts, serous cystadenomas, and neuroendocrine tumors (Latif et al., 1993; Lolkema et al., 2008; van Asselt et al., 2013). In spite of these multiple reports of pancreatic structural lesions, exocrine or endocrine functional defects are often not detected. The exception is Alstrom syndrome, in which β-cell dysfunction and major defects in glucose regulation are hallmarks of disease (Marshall et al., 2011). This is in contrast with another obesity ciliopathy, Bardet–Biedl Syndrome (BBS), in which patients appear to be relatively protected from defects in β-cell function and glucose homeostasis (Lee et al., 2011; Marion et al., 2012). As such, clinical evidence suggests that defects in cilia are directly responsible for pancreatic structural and functional phenotypes. Here, we discuss the potential role of cilia in the development and onset of the more prominent pancreatic defects associated with ciliopathies: pancreatic cysts and disruption of glucose regulation.

PANCREATIC CYSTS

Pancreatic cysts are a heterogenous group of lesions with little known about the origin, pathophysiology, and developmental processes involved. Pancreatic cysts can present with pancreatitis, cystic kidney disease, or alone (Pirro et al., 2003; Khokhar and Seidner, 2004), and can be divided into two categories: benign and neoplastic. Cysts likely result from the abnormal proliferation of a single epithelial cell which eventually expands until it pinches off as an isolated pancreatic cyst, continually expanded by fluid secreted into the cyst lumen (Grantham, 2000; Calvet and Grantham, 2001). Cysts of the pancreas are often accompanied by other phenotypes, including increased proliferation of epithelial cells, acinar cell apoptosis, and dilation of ducts.

The mechanisms by which primary cilia regulate the production of pancreatic cysts are unclear, but substantial evidence from animal models indicates that loss of cilia can lead to their development. For example, perturbation of cilia of the exocrine ductal and centroacinar cells results in pancreatic cyst formation (Cano et al., 2006; Gallagher et al., 2008; Seeley et al., 2009; van Asselt et al., 2013). Defects in cilia in the orpk mouse, lacking expression of the Ift88/Polaris gene which is necessary for ciliary assembly (Pazour et al., 2000; Taulman et al., 2001; Yoder et al., 2002), results in expansion of developing and postnatal ducts, giving rise to cystogenesis (Cano et al., 2004). Interestingly, this ductal expansion is accompanied by apoptosis in the only non-ciliated exocrine cell type, acinar cells, resulting in an overall loss of exocrine tissue and pancreas size (Cano et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). This is consistent with the ductal dilation observed during development and postnatal expansion of animals with a conditional loss of cilia in pancreatic tissue induced by Pdx1-Creearly;Kif3af/ f (Cano et al., 2006). Although both the ductal and endocrine cells were deciliated in those mice, lineage tracing showed that the cysts originated from the ciliated ductal cells. As the mice aged, the pancreatic pathophysiology progressed to loss of acinar tissue, fluid filled cysts, extensive dilation of ductal systems, increasing adipose tissue mass, and eventual fibrosis (Cano et al., 2006). Likewise, loss of Vhl specifically in pancreas gave rise to postnatal development of cysts and microcystic adenoma (Shen et al., 2009). Similar observations were reported from mutant mice deficient for hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 (HNF-6), a transcription factor expressed in the pancreatic progenitor cells regulating Pdx1 expression and the differentiation to ductal cells (Pierreux et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). Loss of Hnf6 expression resulted in an absence of primary cilia from pancreatic ducts, producing enlargement of the lumen and multiple cysts (Kaestner, 2006; Pierreux et al., 2006). HNF6 is believed to play an important role in controlling the expression of Pkhd1 through HNF1 and Cys1 (cystin), thereby regulating the formation of primary cilia (Gresh et al., 2004; Kaestner, 2006; Pierreux et al., 2006). In addition to loss of cilia, impaired ciliary function can also lead to pancreatic cyst formation. Pkd2 and inversin (Invs) are two ciliary proteins that are not required for cilia formation, but mediate cilia function (Wu et al., 2000; Morgan et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2009a). Similar to animals lacking cilia, mice mutated for Pkd2 and Invs exhibit increased ductal structures and reduced acinar tissue (Cano et al., 2004). Similarly, mice lacking the gene implicated in ADPKD, Pkd1, exhibit pancreatic ductal cysts (Lu et al., 1997).

The mechanistic links between primary cilia in pancreas and cystogenesis remain elusive, although it has been proposed that they may function as mechanosensors in the pancreatic ductal cells to measure luminal flow similar to what has been observed in kidney cells (Ong and Wheatley, 2003; Nauli et al., 2003; Nauli and Zhou, 2004). It is possible that the absence of cilia would impede sensing of luminal flow, resulting in increased pressure and defects in other cellular regulatory signals driving proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, ultimately giving rise to cystogenesis. Another possibility is the involvement of microtubule defects associated with loss of ciliary proteins. For example, the VHL protein binds to KIF3A and KAP3 (kinesin-associated protein 3) (Lolkema et al., 2007), but also plays a significant role in ciliary maintenance and stability through its regulation of cell polarity, assembly of the extracellular matrix, and microtubule stability (Esteban et al., 2006; Lutz and Burk, 2006; Schermer et al., 2006). Mutant VHL-induced microtubule instability gives rise to the development of cysts in renal tissue (Esteban et al., 2006) and it is plausible that similar mechanisms may be responsible for the development of pancreatic cysts in VHL.

It is also likely that disruption of signaling as a result of ciliary dysfunction may result in production of cysts either through polarization defects or dedifferentiation that result in aberrant proliferation. HNF-6 deficient mice, for example, exhibit disrupted polarization of ductal epithelial cells as well as mislocalization of β-catenin from the lateral membrane (Pierreux et al., 2006), suggesting a possible role for Wnt signaling and downstream regulation of proliferation. Additionally, the cystic epithelium of Pdx1-Creearly;-Kif3af/f mice expressed high levels of TGF-β ligands, as well as phosphorylated extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), indicating MEK/ERK pathway activation (Cano et al., 2006). These pathways are highly implicated in pancreatic fibrosis and neoplastic transformation (Lee et al., 1995; Sanvito et al., 1995; Hezel et al., 2006), suggesting the possibility of similar pathway deregulation in cilia-driven cystogenesis. Likewise, aberrant activation of Shh signaling may be implicated, given that β-cell specific disruption of cilia and elevation of Shh results in dedifferentiation and aberrant proliferation (Landsman et al., 2011). Similar to the role of cilia during development in inhibiting activation of morphogenetic pathways, it is possible that continual disruption or postnatal ablation of cilia activates those pathways driving proliferative cystogenesis.

IMPAIRED GLUCOSE REGULATION

Disruption of glucose homeostasis in ciliopathies has been discussed primarily in the context of the subgroup of diseases characterized by highly penetrant obesity, which include Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS) and Alstrom syndrome. A majority of BBS and Alstrom patients are obese, potentially as a result of centrally mediated hyperphagia (Arsov et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009; Sherafat-Kazemzadeh et al., 2013), and display complications associated with obesity including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperleptinemia (Beales et al., 1999; Grace et al., 2003; Feuillan et al., 2011; Girard and Petrovsky, 2011). Despite the similarities between the two disorders, the rate of early onset of diabetes is significantly higher in Alstrom patients (Marshall et al., 2005; Marshall et al., 2007; Girard and Petrovsky, 2011) when compared to most cohorts of BBS patients (Beales et al., 1999; Grace et al., 2003; Feuillan et al., 2011), as well as to rates of diabetes in common obesity (Mokdad et al., 2003; Finkelstein, 2008; Bettini et al., 2012). Although this is in large part due to the severe insulin resistance in children afflicted with Alstrom (Marshall et al., 2005) which is not as prevalent in BBS (Beales et al., 1999; Grace et al., 2003; Feuillan et al., 2011), there is evidence to support a role for dysfunction of the endocrine pancreas, namely β-cells. Clinical reports suggest that the progression of diabetes in Alstrom patients is due to failure in insulin secretion from β-cells, without any further worsening of insulin resistance (Green et al., 1989; Moore et al., 2005). Consistent with this possibility, the protein product of the gene mutated in Alstrom, ALMS1, is highly expressed in adult and fetal pancreatic islets (Hearn et al., 2005; Li et al., 2007) and loss of Alms1 expression in mutant mice results in pancreatic hyperplasia, partial degranulation of β-cells, and islet cysts (Collin et al., 2005; Arsov et al., 2006). The extent to which Alms1-deficient β-cells are able to respond to glucose and secrete insulin is unknown. In contrast, insulin secretion increased in C. elegans models of BBS and cultured mouse insulinoma cells (Min6), an in vitro model for β-cells, exhibited enhanced insulin secretion in the absence of Bbs gene expression (Lee et al., 2011). Consistently, mouse models of BBS exhibit increased insulin sensitivity and normal glucose management (Marion et al., 2012). These findings suggest that ciliary proteins may play discrepant roles in the regulation of β-cell function or, potentially, the cilium maintains a delicate balance between enhanced and depleted β-cell function.

Although little is known about the role of BBS and Alstrom proteins per se, there is evidence to suggest that cilia in general are important in β-cell differentiation and function. Rfx3, a transcription factor necessary for ciliogenesis (Bonnafe et al., 2004), is expressed in Ngn3+ endocrine progenitor cells in the developing mouse pancreas as well as in differentiated endocrine cells, including β-cells (Ait-Lounis et al., 2007). Mice deficient in this transcription factor possess fewer β-cells, α-cells, and ε-cells during perinatal stages. Furthermore, the adult mice exhibit smaller islets, decreased insulin production, reduced glucose stimulated insulin secretion, and impaired glucose tolerance (Ait-Lounis et al., 2007). Assessment of developing Rfx3−/− mice revealed abnormal β-cell development at E15.5, indicated by the presences of accumulated β-cell precursors and defective β-cells expressing decreased Insulin, Glut2, and Glucokinase (Ait-Lounis et al., 2010). Consistent with the role of Rfx3 in ciliogenesis, the endocrine cells of Rfx3−/− mice also exhibited reduced and shortened primary cilia (Ait-Lounis et al., 2007), suggesting an important role of cilia in the development and maintenance of endocrine cells as well as in the maintenance of normal glucose homeostasis. This potential role is supported by the loss of β-cell differentiation when cilia are ablated specifically in β-cells, along with increased Shh signaling (Landsman et al., 2011). Although further investigation is required to determine the exact role of cilia and ciliopathy proteins in the function and maintenance of β-cells and other endocrine cell types, the emerging evidence suggests that disruption of glucose regulation in ciliopathies—and potentially in more common diseases—may be directly linked to the regulation of signaling that is highly dependent on cilia and is critical to proper pancreatic morphogenesis.

Conclusions

Primary cilia have been established as important mediators of many developmental signaling pathways and the developing pancreas is highly reliant on pathways that have been clearly linked to cilia including Shh, Wnt, FGF, Notch, and TGF-β. It is therefore not surprising that disruption of cilia gives rise to disruption of both pancreatic morphology and function. However, the extent to which pancreatic morphogenesis and homeostasis is reliant on ciliary function to maintain proper signaling is unknown. Furthermore, the involvement of cilia in regulation of other pathways necessary for pancreatic development, such as retinoic acid signaling, is unclear. Future studies investigating the specific role in pancreas played by proteins associated with cilia and ciliopathies will be necessary not only to clarify the extent to which cilia can be linked to pancreatic phenotypes but also to achieve a more complete understanding of pancreatic development and function in general.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health [K01DK092402 (N.A.Z.) and T32AG000219 (E.A.O.)]

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- Ahnfelt-Ronne J, Hald J, Bodker A, et al. Preservation of proliferating pancreatic progenitor cells by Delta-Notch signaling in the embryonic chicken pancreas. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Lounis A, Baas D, Barras E, et al. Novel function of the ciliogenic transcription factor RFX3 in development of the endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 2007;56:950–959. doi: 10.2337/db06-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Lounis A, Bonal C, Seguin-Estevez Q, et al. The transcription factor Rfx3 regulates beta-cell differentiation, function, and glucokinase expression. Diabetes. 2010;59:1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/db09-0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaba ARI. Gli proteins encode context-dependent positive and negative functions: implications for development and disease. Development. 1999;126:3205–3216. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andralojc KM, Mercalli A, Nowak KW, et al. Ghrelin-producing epsilon cells in the developing and adult human pancreas. Diabetologia. 2009;52:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelqvist A, Ahlgren U, Edlund H. Sonic hedgehog directs specialised mesoderm differentiation in the intestine and pancreas. Curr Biol. 1997;7:801–804. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsov T, Silva DG, O’Bryan MK, et al. Fat Aussie—a new Alstrom syndrome mouse showing a critical role for ALMS1 in obesity, diabetes, and spermatogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1610–1622. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aughsteen AA. The ultrastructure of primary cilia in the endocrine and excretory duct cells of the pancreas of mice and rats. Eur J Morphol. 2001;39:277–283. doi: 10.1076/ejom.39.5.277.7380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AzaBlanc P, RamirezWeber FA, Laget MP, et al. Proteolysis that is inhibited by Hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell. 1997;89:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek SH, Kioussi C, Briata P, et al. Regulated subset of G1 growth-control genes in response to derepression by the Wnt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3245–3250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330217100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JM, Mohr AM, Hollingsworth MA. Sonic hedgehog paracrine signaling regulates metastasis and lymphangiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:3513–3525. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth B, Burdick J. Anatomy, histology, embryology, and developmental anomalies of the pancreas. In: Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: Pathophysiology/diagnosis/management. 9. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier Inc; 2010. pp. 909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Beales P, Kenny T. Towards the diagnosis of a ciliopathy. In: Kenny T, Beales P, editors. Ciliopathies: A reference for clinicians. Oxford University Press New York; New York: 2014. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Beales PL, Elcioglu N, Woolf AS, et al. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet. 1999;36:437–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatus P, Lendahl U. Notch and neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981015)54:2<125::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann C, Fliegauf M, Bruchle NO, et al. Loss of nephrocystin-3 function can cause embryonic lethality, Meckel-Gruber-like syndrome, situs inversus, and renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:959–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Chandra M, Creswell J, et al. Renal-Hepatic-Pancreatic dysplasia - A syndrome reconsidered. Am J Med Genet. 1987;26:391–403. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettini V, Maffei P, Pagano C, et al. The progression from obesity to type 2 diabetes in Alstrom syndrome. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:59–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, et al. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a wingless receptor. Nature. 1996;382:225–230. doi: 10.1038/382225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan A, Itoh N, Kato S, et al. Fgf10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development. 2001;128:5109–5117. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood MJ, McMahon AP. Hedgehog and bmp genes are coexpressed at many diverse sites of cell-cell interaction in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 1995;172:126–138. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonal C, Herrera PL. Genes controlling pancreas ontogeny. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:823–835. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072444cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnafe E, Touka M, AitLounis A, et al. The transcription factor RFX3 directs nodal cilium development and left-right asymmetry specification. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4417–4427. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4417-4427.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S. Islets of langerhans: Morphology and post-natal growth. In: Kahn CR, Smith RJ, Jacobson AM, Weir GC, King EL, editors. Joslin’s diabetes mellitus. 14. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Boquist L. Cilia in normal and regenerating islet tissue. An utlrastructural study in the Chinese hamster with particular reference to the B-cells and the ductular epithelium. Z Zellforsch mikrosk Anat. 1968;89:519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens L, Rooman I. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1255–1270. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody SL, Yan XH, Wuerffel MK, et al. Ciliogenesis and left-right axis defects in forkhead factor HFH-4-null mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:45–51. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.1.4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffa R, Capella C, Solcia E, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) cells in the pancrease and gastrointestinal mucosa. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Histochemistry. 1977;50:217–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00491069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlison JS, Long Q, Fujitani Y, et al. Pdx-1 and Ptf1a concurrently determine fate specification of pancreatic multipotent progenitor cells. Dev Biol. 2008;316:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher D, Ruther U. Expression profile of Gli family members and Shh in normal and mutant mouse limb development. Dev Dyn. 1998;211:88–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199801)211:1<88::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvet JP, Grantham JJ. The genetics and physiology of polycystic kidney disease. Sem Nephrol. 2001;21:107–123. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano DA, Murcia NS, Pazour GJ, Hebrok M. Orpk mouse model of polycystic kidney disease reveals essential role of primary cilia in pancreatic tissue organization. Development. 2004;131:3457–3467. doi: 10.1242/dev.01189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano DA, Sekine S, Hebrok M. Primary cilia deletion in pancreatic epithelial cells results in cyst formation and pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1856–1869. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli G, LaRochelle WJ, Mackem S, et al. Soluble dominant-negative receptor uncovers essential roles for fibroblast growth factors in multi-organ induction and patterning. Embo J. 1998;17:1642–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes S, Lau J, Cano DA, et al. Primary cilia regulate Gli/Hedgehog activation in pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10109–10114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin Y. Enterochromaffin (EC-(cells of the mammalian gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) endocrine system—cellular sources of prodynorphin-derived peptides. Cell Tissue Res. 1988;253:173–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00221752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-F, Serra R. Ift88 regulates Hedgehog signaling, Sfrp5 expression, and beta-catenin activity in post-natal growth plate. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:350–356. doi: 10.1002/jor.22237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty-John S, Piwnica-Worms K, Bryant J, et al. Fibrocystic disease of liver and pancreas; under-recognized features of the X-linked ciliopathy oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 (OFD I) Am J Med Genet Part A. 2010;152A:2640–2645. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver O, Melton DA. Development of the endocrine pancreas. In: Kahn CR, Smith RJ, Jacobson AM, Weir GC, King EL, editors. Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus. 14. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Clement CA, Ajbro KD, Koefoed K, et al. TGF-β signaling is associated with endocytosis at the pocket region of the primary cilium. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1806–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MH, Sawyer JM, Afelik S, Jensen J, Leach SD. Exocrine ontogenies: On the development of pancreatic acinar, ductal and centroacinar cells. Sem Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin GB, Cyr E, Bronson R, et al. Alms1-disrupted mice recapitulate human Alstrom syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2323–2333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, et al. Vertebrate smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit KC, Shyer AE, Dowdle WE, et al. Kif3a constrains β-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:70–76. doi: 10.1038/ncb1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cras-Meneur C, Li L, Kopan R, Permutt MA. Presenilins, Notch dose control the fate of pancreatic endocrine progenitors during a narrow developmental window. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2088–2101. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisera CA, Rose MI, Connelly PR, et al. The ontogeny of TGF-β1, -β2, -β3, and TGF-β receptor-II expression in the pancreas: implications for regulation of growth and differentiation. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:689–694. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessimoz J, Bonnard C, Huelsken J, Grapin-Botton A. Pancreas-specific deletion of beta-catenin reveals Wnt-dependent and Wnt-independent functions during development. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1677–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch G, Jung JN, Zheng MH, et al. A bipotential precursor population for pancreas and liver within the embryonic endoderm. Development. 2001;128:871–881. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Magliano MP, Sekine S, Ermilov A, et al. Hedgehog/Ras interactions regulate early stages of pancreatic cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3161–3173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1470806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichmann DS, Miller CP, Jensen J, et al. Expression and misexpression of members of the FGF and TGFβ families of growth factors in the developing mouse pancreas. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:663–674. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echelard Y, Epstein DJ, Stjacques B, et al. Sonic-hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity. Cell. 1993;75:1417–1430. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elayat AA, Elnaggar MM, Tahir M. An immunocytochemical and morphometric study of the rat pancreatic-islets. J Anat. 1995;186:629–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghazi L, Cras-Meneur C, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Role for FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals in controlling pancreatic endocrine progenitor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3884–3889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062321799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh-Yamagami S, Evangelista M, Wilson D, et al. The mammalian Cos2 homolog Kif7 plays an essential role in modulating Hh signal transduction during development. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1320–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban MA, Harten SK, Tran MG, Maxwell PH. Formation of primary cilia in the renal epithelium is regulated by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1801–1806. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty EJ, Stokes N, Chai S, et al. A role for the primary cilium in notch signaling and epidermal differentiation during skin development. Cell. 2011;145:1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijen A, Goumans MJ, van den AJ, Raaij E-V. Expression of activin subunits, activin receptors and follistatin in postimplantation mouse embryos suggests specific developmental functions for different activins. Development. 1994;120:3621–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuillan PP, Ng D, Han JC, et al. Patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome have hyperleptinemia suggestive of leptin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E528–E535. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick GM, Johnson AM, Hammond WS, Gabow PA. Causes of death in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney-disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2048–2056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MM. The prevalence of diabetes among overweight and obese individuals is higher in poorer than in richer neighbourhoods. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Frank V, Habbig S, Bartram MP, et al. Mutations in NEK8 link multiple organ dysplasia with altered Hippo signalling and increased c-MYC expression. Hum Molr Genet. 2013;22:2177–2185. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura J, Hosoda K, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Rbp-j regulates expansion of pancreatic epithelial cells and their differentiation into exocrine cells during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2779–2791. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa M, Eto Y, Kojima I. Expression of immunoreactive activin A in fetal rat pancreas. Endocr J. 1995;42:63–68. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.42.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher A-R, Esquivel EL, Briere TS, et al. Biliary and pancreatic dysgenesis in mice harboring a mutation in Pkhd1. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:417–429. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasa R, Mrejen C, Leachman N, et al. Proendocrine genes coordinate the pancreatic islet differentiation program in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13245–13250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405301101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes JM, Liu Y, Zaghloul NA, et al. Disruption of the basal body comprises proteasomal function and perturbs intra-cellular Wnt response. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1350–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes JM, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. 2009;137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghossoub R, Molla-Herman A, Bastin P, Benmerah A. The ciliary pocket: a once-forgotten membrane domain at the base of cilia. Biol Cell. 2011;103:131–144. doi: 10.1042/BC20100128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard D, Petrovsky N. Alstrom syndrome: insights into the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:77–88. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Githens S. The pancreatic duct cell—proliferative capabilities, specific characteristics, metaplasia, isolation, and culture. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:486–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Githens S. Pancreatic duct cell-cultures. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:419–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes GK. Developmental biology of the pancreas: a comprehensive review. Dev Biol. 2009;326:4–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes GK, Galante PE, Hanahan D, et al. Lineage-specific morphogenesis in the developing pancreas: role of mesenchymal factors. Development. 1996;122:439–447. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, Scott MP. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, Nomura M, Tanaka K, et al. Genetic interactions between activin type IIB receptor and Smad2 genes in asymmetrical patterning of the thoracic organs and the development of pancreas islets. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2865–2874. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace C, Beales P, Summerbell C, et al. Energy metabolism in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Int J Obes. 2003;27:1319–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham JJ. Time to treat polycystic kidney diseases like the neoplastic disorders that they are. Kidney Int. 2000;57:339–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grapin-Botton A. Endoderm specification. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Stem Cell Institute; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JS, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, et al. The cardinal manifestations of Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a form of Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1002–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910123211503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider MH, Elliot DW. Election microscopy of human pancreatic tumors of islet cell origin. Am J Pathol. 1964;44:663–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresh L, Fischer E, Reimann A, et al. A transcriptional network in polycystic kidney disease. Embo J. 2004;23:1657–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu GQ, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129:2447–2457. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu GQ, Brown JR, Melton DA. Direct lineage tracing reveals the ontogeny of pancreatic cell fates during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2003;120:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon EB, Apelqvist AA, Smart NG, et al. GDF11 modulates NGN3(+) islet progenitor cell number and promotes beta-cell differentiation in pancreas development. Development. 2004;131:6163–6174. doi: 10.1242/dev.01535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A, Papadopoulou S, Edlund H. Fgf10 maintains notch activation, stimulates proliferation, and blocks differentiation of pancreatic epithelial cells. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:185–193. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, et al. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intra-flagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. Plos Genet. 2005;1:480–488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Semenov M, Tamai K, Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn T, Spalluto C, Phillips VJ, et al. Subcellular localization of ALMS1 supports involvement of centrosome and basal body dysfunction in the pathogenesis of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:1581–1587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok M. Hedgehog signaling in pancreas development. Mech Dev. 2003;120:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok M, Kim SK, Melton DA. Notochord repression of endodermal Sonic hedgehog permits pancreas development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1705–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok M, Kim SK, St-Jacques B, et al. Regulation of pancreas development by hedgehog signaling. Development. 2000;127:4905–4913. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi P, Petersen O. The exocrine pancreas: The acinarductal tango in physiology and pathophysiology. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;165:1–30. doi: 10.1007/112_2013_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser PW, Lau J, Taketo MM, et al. Stabilization of beta-catenin impacts pancreas growth. Development. 2006;133:2023–2032. doi: 10.1242/dev.02366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller RS, Dichmann DS, Jensen J, et al. Expression patterns of Wnts, Frizzleds, sFRPs, and misexpression in transgenic mice suggesting a role for Wnts in pancreas and foregut pattern formation. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:260–270. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman B, Wallgren A, Hellerstrom C. Two types of islet alpha cells in different parts of the pancreas of the dog. Nature. 1962;194:1201–1202. doi: 10.1038/1941201a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera PL, Nepote V, Delacour A. Pancreatic cell lineage analyses in mice. Endocrine. 2002;19:267–277. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:19:3:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, et al. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]