Abstract

Background

Imatinib mesylate is a selective tyrosine‐kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of multiple cancers, most notably chronic myelogenous leukemia. There is evidence that imatinib can induce cardiotoxicity in cancer patients. Our hypothesis is that imatinib alters calcium regulatory mechanisms and can contribute to development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Methods and Results

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were treated with clinical doses (low: 2 μM; high: 5 μM) of imatinib and assessed for molecular changes. Imatinib increased peak systolic Ca2+ and Ca2+ transient decay rates and Western analysis revealed significant increases in phosphorylation of phospholamban (Thr‐17) and the ryanodine receptor (Ser‐2814), signifying activation of calcium/calmodulin‐dependent kinase II (CaMKII). Imatinib significantly increased NRVM volume as assessed by Coulter counter, myocyte surface area, and atrial natriuretic peptide abundance seen by Western. Imatinib induced cell death, but did not activate the classical apoptotic program as assessed by caspase‐3 cleavage, indicating a necrotic mechanism of death in myocytes. We expressed AdNFATc3‐green fluorescent protein in NRVMs and showed imatinib treatment significantly increased nuclear factor of activated T cells translocation that was inhibited by the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 or CaMKII inhibitors.

Conclusion

These data show that imatinib can activate pathological hypertrophic signaling pathways by altering intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. This is likely a contributing mechanism for the adverse cardiac effects of imatinib.

Keywords: cancer pharmacology, calcium, hypertrophy, molecular biology

Introduction

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is caused by the formation of the fusion protein, Bcr‐Abl,1 which develops from a translocation between chromosomes 9 (Abl) and 22 (Bcr); the mutated chromosome is known as the Philadelphia chromosome. The mutant Bcr‐Abl protein is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that can induce malignancies. This mutant protein activates cell survival pathways and inhibits cell death pathways2 and is responsible for more than 90% of all cases of CML.1

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are a relatively new class of anticancer drugs that target cellular pathways overexpressed in certain types of tumors. Imatinib mesylate (IM) is a TKI and CML therapeutic that inhibits the constitutively active Bcr‐Abl tyrosine kinase.3 It has been FDA approved since 2001.4 IM ameliorates cellular proliferation and induces more than 70% cytogenic remission in CML patients.

Recent clinical studies suggest that IM can have off target effects and can induce cardiotoxicity in patients.5, 6, 7 In one particular study, all of the patients evaluated (10 individuals) had normal left ventricular function before IM therapy was introduced (ejection fraction 56 ± 7%), but presented with indicators of heart failure including significant volume overload and symptoms corresponding to a New York Heart Association (NYHA) class 3–4 heart failure (mean NYHA class 3.5 ± 0.5; p < 0.001 vs. pretreatment) and a reduction in ejection fraction to 25 ± 8% (p < 0.001 vs. pretreatment) associated with mild left ventricular (LV) dilation 1–14 months (mean of 7.2 ± 5.4 months) following initiation of treatment.5 Another study indicated that IM treatment‐induced heart failure accompanied by extraordinarily high concentrations of natriuretic peptide precursor B (BNP), an indicator of hypertrophy and heart failure, in patients being treated for gastrointestinal stromal tumors.6 An additional study assessing LV systolic and diastolic function on patients receiving TKIs (including IM) by tissue Doppler echocardiography showed significant decreases in mean LV ejection fraction and LV stroke volume values in subjects receiving IM.7

These clinical findings have been followed up with animal studies to more clearly define the basis of the adverse cardiovascular effects of IM. Mice chronically treated with clinical dosages of IM8 had reduced contractile function, LV dilation, and diminished LV mass.5 However, cardiomyocytes from the LV of IM‐treated mice displayed an increase in size, in conjunction with Ca2+‐induced mitochondrial swelling. These finding suggest that IM may have induced myocyte hypertrophy and possibly mitochondrial based cell death.9

In the present study we examined the hypothesis that IM treatment alters myocyte Ca2+ handling, induces cardiac hypertrophy, and causes cell death. Two different doses of IM were used (low: 2 μM; high: 5 μM) based on clinical evaluations of plasma concentrations of CML patients receiving IM treatment and previously described in vivo and in vitro studies.5, 10, 11 Our experiments showed that neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) treated with IM develop pathological hypertrophy with increased expression of the hypertrophic marker atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP).12 IM treated myocytes exhibited enhanced Ca2+ transients and more rapid Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). IM‐induced CaMKII mediated phospholamban (PLB) phosphorylation, which resulted in enhanced SR function.13 IM treated NRVMs developed pathological hypertrophy via activation of Calcineurin (Cn)‐nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (NFAT) signaling and at high doses myocyte death was observed which was independent of caspase‐3 activation, indicating necrosis rather than programmed apoptosis in these cells.14, 15 These data show that IM activates Ca2+‐dependent hypertrophic pathways and also can induce necrotic cell death.

Methods

NRVM isolation and culture

All animal procedures were approved by the Temple University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. NRVMs were isolated from 1‐ to 3‐day‐old Sprague Dawley rats as described previously.16, 17, 18 NRVMs were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 5% fetal bovine serum for 24 hours. The cells were then cultured in serum‐free media and treated with 2 or 5 μM IM. The 100‐mg capsules were dissolved in distilled water and insoluble material was removed by repeated centrifugation at 2,500×g to yield highly purified material.19 NRVMs were exposed to IM at 37 °C for 72 hours. An adenovirus containing a dominant negative CaMKIIδc (CaMKII‐DN) was used at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. The following inhibitors were added to the NRVM cultures for experiments: autocamtide 2‐related inhibitory peptide (AIP‐1 μM; Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and the L‐type calcium channel (LTCC) blocker Nifedipine.

Mouse myocyte isolation and culture

Anesthesia was induced in mice using 3% isoflurane and maintained using 1% isoflurane delivered by nose cone. Adequacy of anesthesia was evaluated by monitoring hind limb reflexes. When unconscious state was induced, mouse hearts were excised from the thorax and cannulated on a constant‐flow Langendorff apparatus. The heart was digested by retrograde perfusion of normal Tyrode's solution containing 180 U/mL collagenase and (mM): CaCl2 0.02, glucose 10, HEPES 5, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.2, NaCl 150, and sodium pyruvate 2, pH 7.4. When the tissue softened, the left ventricle was isolated and gently minced, filtered, and equilibrated in Tyrode's solution with 0.2 mM CaCl2, and 1% bovine serum albumin at room temperature.20 Myocytes were incubated with 2 μM or 5 μM IM for 12 hours and then collected for Western analysis.

Cell count and volume measurements

To determine if IM‐induced cellular hypertrophy, myocyte counts were measured in NRVMs as described in detail previously.21, 22, 23 Cell volume was measured using a Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA), after the NRVMs were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution and trypsinized.24

NFATc3‐GFP infection and analysis

NRVMs pretreated with IM were infected with an adenovirus encoding NFATc3–GFP to monitor NFAT localization. In normal NRVMs NFAT‐GFP is found in the cytoplasm. Four micromolar calcium was used as a positive control, to induce NFAT‐GFP nuclear translocation. The Cn inhibitor FK506 (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used as a Cn‐NFAT translocation inhibitor.16 After infection, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 minutes and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X‐100 immediately before labeling with antibodies directed against α‐actinin. Staining of α‐actinin and 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) were performed to detect myocytes and location of NFAT‐GFP. Fixed cells on coverslips were mounted onto slides and observed with a confocal microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). Images were analyzed with EZ‐C1 FreeViewer (Nikon) and ImageJ (NIH) software. NFAT localization was quantified as the normalized nucleus/cytoplasm ratio of GFP fluorescence intensity (NFATn/c).25

Ca2+ transients

NRVMs were grown on glass coverslips coated with laminin and were treated with 2 or 5 μM IM. The glass coverslips were broken and pieces with affixed myocytes were placed in a heated chamber (35 °C) on the stage of an inverted microscope and perfused with a normal physiological tyrodes solution containing (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 2 Na‐pyruvate, 1 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES, pH 7.4. Myocytes were loaded with 10 μM Fluo‐4 AM (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 15 minutes and then washed to measure [Ca2+]i transients. Myocytes were paced at 0.5 Hz. For fluorescence measurements, the F 0 (or F unstimulated) was measured as the average fluorescence for the 50 ms prior to stimulation. Ca2+ transients are reported as F/F 0.26

Electrophysiology

Adult mouse ventricular myocytes were isolated as described above and were incubated with or without 5 μM imatinib in normal tyrodes for 16–20 hours. L‐type calcium channel current was measured in Na+‐ and K+‐free solution with a holding potential at –50. Once baseline currents were measured, 100 nM isoproterenol was added and currents were measured again.20

Western blotting

Cytoplasmic and membrane protein were isolated from cultured NRVMs using phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) lysis buffer containing: 0.5% Triton X‐100, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH 7.4), phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF and 0.1 mM NaVO4), proteinase inhibitors (10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 8 μg/mL calpain inhibitor I and II, and 200 μg/mL benzamidine). Cardiac actin was isolated from resulting pellet using PBS lysis buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Fisher Biotech, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), 1% IGEPAL CA‐630 (Sigma), 0.5% deoxycholate (Sigma), 5 mM EDTA (pH 7.4), and proteinase inhibitors. Protein abundance and phosphorylation levels in isolated protein were analyzed with Western blot analysis as described previously.27 Target antigens were probed with the following antibodies: Na+–Ca2+ exchanger protein (NCX; Swant, Marly, Switzerland), PLBt (Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA, USA), RyR (Research Diagnostics, Minneapolis, MN, USA), α‐sarcomeric actin and SERCA (Sigma), ANP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), GAPDH (AbD Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom), LTCC‐α1C subunit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), S2814‐RyR, PS16‐PLB, and PT17‐ PLB (Badrilla, Leeds, United Kingdom), Cleaved Caspase 3 and full length Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Rabbit‐ and mouse‐horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfront, United Kingdom) were used and Westerns were developed with Western Lightening Enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Paired and unpaired t‐test and ANOVA were used to test for significance with GraphPad Prism 5.0. For all tests, statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Imatinib treatment increases Ca2+ transients and alters the abundance and phosphorylation state of Ca2+ regulatory proteins

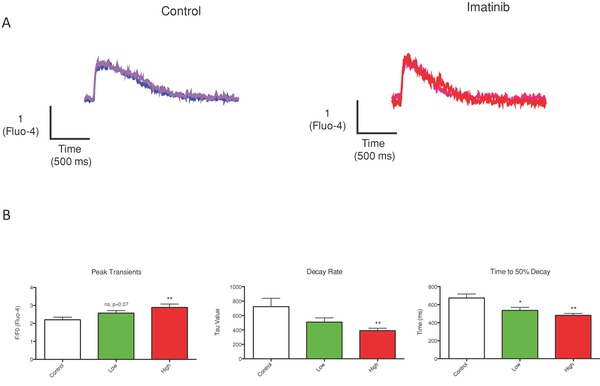

Ca2+ transients were measured in paced NRVMs. Imatinib treatment increased peak systolic Ca2+ and increased its rate of decay (Tau). The duration of the Ca2+ transient was also reduced. All of these effects are consistent with a stimulation of SR Ca2+ uptake, storage, and release (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Imatinib increases Ca2+ transient amplitude and accelerates the rate of decay. Ca2+ transient characteristics were measured after IM treatment. (A) Representative traces are shown. (B) IM caused a significant increase in the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ transients, increased decay rate, and shortened the time to 50% decay. *p < 0.05 from control, ** p < 0.01 from control.

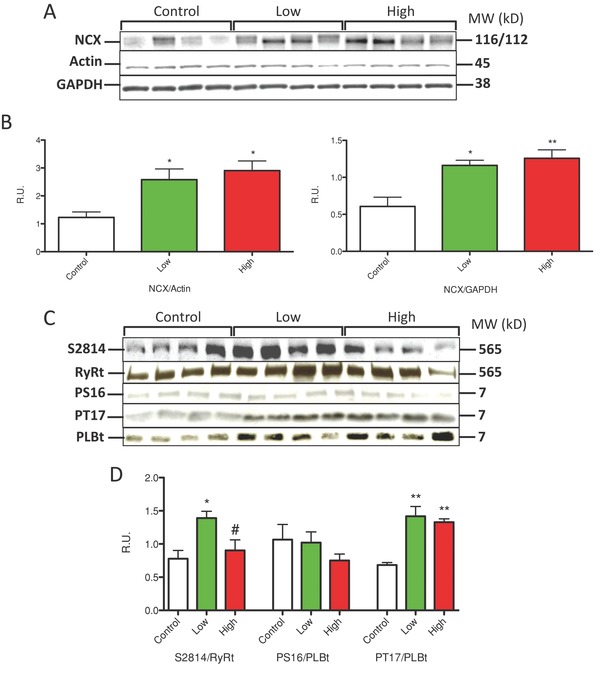

Increases in peak systolic Ca2+ transient amplitude and enhanced SR Ca2+ uptake suggest changes in the abundance and phosphorylation of Ca2+ regulatory proteins after IM treatment. IM caused a dose‐dependent increase in the abundance of the major myocyte Ca2+ efflux molecule, the Na/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX; Figure 2A and B). This finding supports the idea that SR dependent Ca2+ transients are increased after IM treatment and myocytes adapt by increasing the abundance of Ca2+ export proteins, to maintain Ca2+ flux balance. There was no effect on the abundance of other Ca2+ regulatory proteins studied: ryanodine receptor (RyRt), L‐type Ca2+ channel (α1C, pore‐forming subunit), SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), and PLB (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Imatinib treatment altered the abundance and phosphorylation state of Ca2+ handling proteins. NRVMs were treated with Imatinib at low (2 μM) and high concentrations (5 μM). (A and B) NCX abundance was quantified with Actin or GAPDH. (C) Representative western analysis of RyR (RyRS2814) and PLB (S16 and T17) are shown. (D) Changes in phosphorylation state of RyRS2814 and PLB‐T17 (CaMKII sites) but not PLB‐S16 (PKA site) were found in IM‐treated myocytes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 from control; #p < 0.05 from low.

The increased decay rate of the Ca2+ transient after IM treatment suggests that SR Ca2+ uptake was enhanced. SR Ca2+ uptake rates are regulated by phosphorylation of the SERCA regulatory protein PLB. This phosphorylation usually results from activation of protein kinase A (PKA; phosphorylates PLB‐Serine 16) or secondarily CaMKII (phosphorylates PLB‐threonine 17). Imatinib treatment had no effect on PLB‐S16 phosphorylation, but caused a significant increase in phosphorylation of PLB‐T17 at both low and high IM doses (Figure 2C and D). The enhanced phosphorylation of PLB‐Thr17 suggests that IM treatment led to the activation of CaMKII, possibly secondary to the increased Ca2+ transients. We also determined that phosphorylation of the RyR at S2814 (also a CaMKII phosphorylation site) was significantly enhanced with Low (2 μM) IM (Figure 2C and D). Collectively these studies suggest that IM treatment increases myocyte Ca2+ transients and an increase in CaMKII mediated phosphorylation of Ca2+ regulatory proteins is involved in this Ca2+ regulatory remodeling.

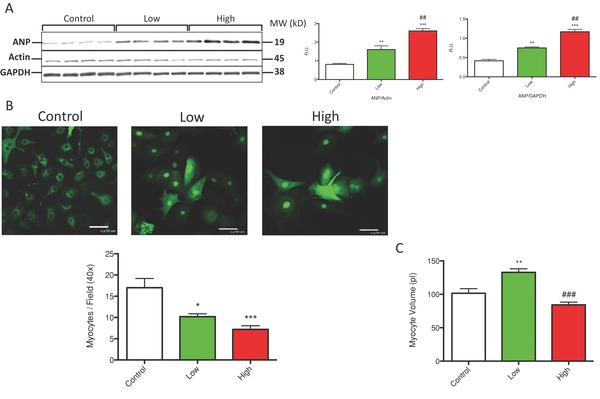

Imatinib treatment causes pathological hypertrophy and myocyte death

Persistent increases in myocyte Ca2+ are linked to pathological hypertrophy and cell death.28 IM caused a dose‐dependent increase in ANP abundance. ANP is a molecule expressed in myocytes with pathological hypertrophy (Figure 3A). IM treatment caused myocyte hypertrophy, as evidenced by an increase in myocyte volume at low concentrations (Con‐102 pl; imatinib‐133 pl. p < 0.05, Figure 3C). However, at high concentrations, average myocyte volume was not different from control even though large myocytes were visible (Figure 3B). Interestingly, while large myocytes were present after treatment with high IM concentrations, fewer myocytes were present, supporting IM‐induced cell death (Figure 3B). These results suggest that IM treatment activates pathological hypertrophy signaling. In addition, IM treatment caused cell death as evidenced by a reduced number of myocytes per field. The IM‐mediated cell death was dose dependent (Figure 3B). These results suggest that high IM treatment induces cardiac hypertrophy but also induces cell death.

Figure 3.

Imatinib treatment induced pathological hypertrophy and cell death. (A) Western analysis of ANP is shown. ANP abundance was normalized with actin and GAPDH. (B) NRVMs infected with AdNFATc3‐GFP are shown. Myocytes treated with IM were decreased in number per field. (C) Average myocyte volume was quantified via Coulter counter from four experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 from control; #p < 0.05, ##p <0.01, ###p < 0.001 from low.

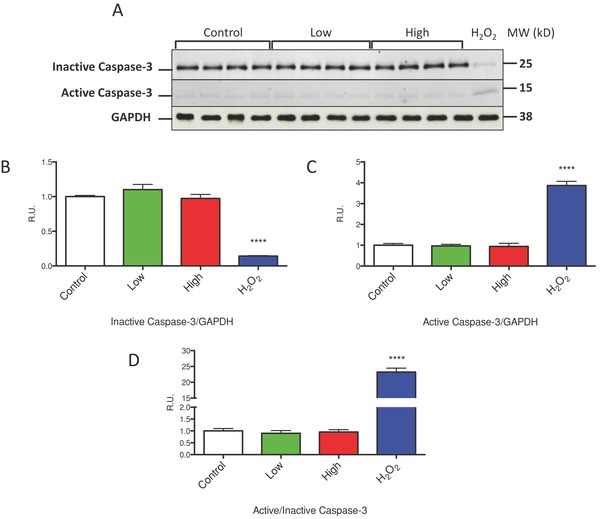

To further explore the mechanism by which IM treatment induces cell death we assayed adult myocytes treated with low and high dose IM for 12 hours for activation of caspase‐3. Caspase‐3 normally exists as an inactive proenzyme in cells and, upon the induction of the classical apoptotic cell death program, is proteolytically processed to an active enzyme that plays a central role in subsequent apoptotic cell death.29 We assessed IM‐induced caspase‐3 cleavage and activation by Western analysis and found no activation at either low or high dose IM treatment (Figure 4A–D). A positive control was included in which caspase‐3 was activated in isolated myocytes by exposure to H2O2. Therefore, we conclude that cell death observed with IM treatment appears to be due to necrotic cell death rather than via programmed apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Imatinib treatment does not induce classical apoptotic cell death. (A) Western analysis of inactive (full length) and active (cleaved) caspase‐3 in isolated ventricular myocytes treated with low and high dose IM is shown. (B) Westerns were quantified and data is represented as inactive caspase‐3 relative to GAPDH, (C) Active caspase‐3 relative to GAPDH, and (D) Active caspase‐3 relative to inactive caspase‐3. Isolated myocytes treated with 100 μM H2O2 were used as a positive control. ****p < 0.0001 from control.

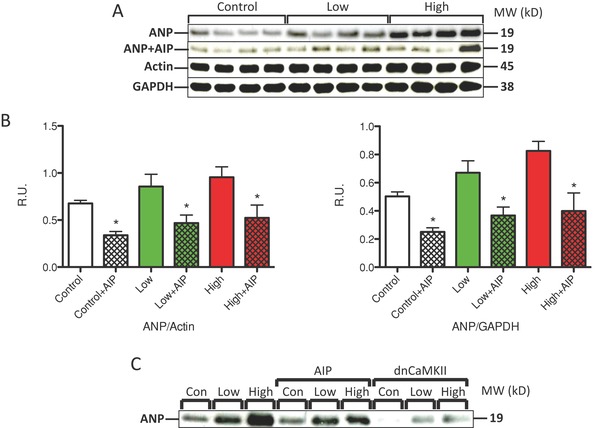

To examine the putative role of CaMKII in IM‐induced myocyte hypertrophy, NRVMs were pretreated with the CaMKII inhibitor, AIP, and then treated with IM (Figure 5A and B). Western blot analysis showed that AIP reduced ANP abundance under all conditions. NRVMs were also coinfected with a dominant negative CaMKII30 (CaMKII‐DN) at an MOI of 100 (Figure 5C). CaMKII‐DN caused a significant reduction in ANP protein abundance under all conditions. These results strongly support the idea that CaMKII plays a key role in IM‐induced pathological hypertrophy.

Figure 5.

Hypertrophy induced by imatinib is reduced by inhibitors of CaMKII signaling. (A) IM‐treated NRVMs were also treated with the CaMKII inhibitor AIP (1 μM). A representative Western blot is shown. ANP was normalized with GAPDH and cardiac actin. (B) AIP reduced ANP expression under all conditions. (C) Western analysis of IM‐treated NRVMs also treated with AIP or infected with dnCaMKII (MOI 100). *p < 0.05 versus control.

Imatinib causes calcineurin‐induced nuclear NFAT translocation

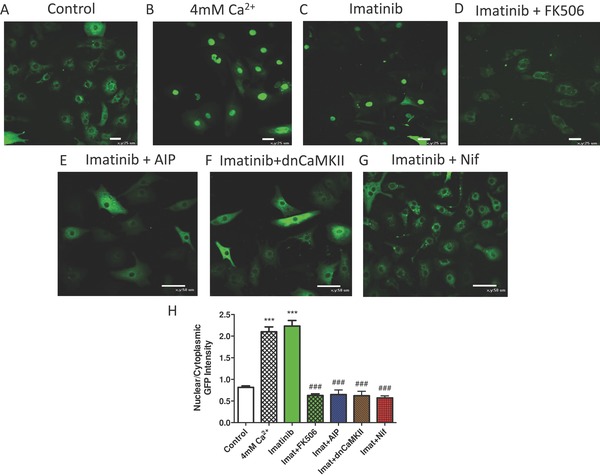

Persistent increases in Ca2+ influx are known to activate Cn‐NFAT signaling and pathological hypertrophy.31 IM treatment did not cause an increase in the L‐type Ca2+ current under any conditions tested (not shown), consistent with Western analysis of channel protein abundance. Therefore, the source of Ca2+ to increase the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was not elucidated. To determine if IM treatment leads to activation of Cn‐NFAT signaling, NRVMs were infected with an adenovirus to induce expression of an NFAT‐GFP construct that we have used previously.25 NFAT‐GFP was found in the cytoplasm of control myocytes under baseline conditions (Figure 6A). NFAT‐GFP nuclear translocation was induced by elevation of bath Ca2+ (Figure 6B). IM treatment at both low and high doses caused significant NFAT‐GFP nuclear translocation, similar to the effect produced by increasing bath Ca2+ (Figure 6C). The Cn inhibitor FK506 abolished IM effects; documenting that IM treatment caused NFAT‐GFP nuclear translocation via a Cn dependent mechanism (Con‐0.8162 ± 0.032; imatinib‐2.233 ± 0.13; imatinib+FK506–0.6277 ± 0.037; p < 0.05). The CaMKII inhibitor AIP and coexpression of a dominant negative CaMKII construct (dnCaMKII) also eliminated IM‐induced NFAT‐GFP nuclear translocation . Finally, the L‐type Ca2+ channel inhibitor Nifedipine abolished IM‐mediated NFAT nuclear translocation (Figure 6D–G).

Figure 6.

Imatinib treatment causes NFAT nuclear translocation. NRVMs were infected with AdNFATc3‐GFP and treated with (A) normal media, (B) +4 mM Ca2+, (C) low dose Imatinib, low dose Imatinib with (D) 2 μM FK506, (E) 1 μM AIP, (F) dnCamKII (MOI of 100), and (G) 10 μM Nifedipine. (H) NFAT Nuclear GFP intensity was normalized to cytoplasmic GFP intensity ([A] n = 52, [B] n = 47, [C] n = 55 [D] n = 43, [E] n = 53, [F] n = 51, and [G] n = 50). ***p < 0.001 from control; ###p < 0.001 from 4 mM Ca2+ and low.

Discussion

TKIs are a relatively new class of anticancer drugs that target cellular pathways overexpressed in certain types of tumors.32 The introduction of IM as a therapeutic targeted against the Bcr‐Abl fusion protein represents one of the most prominent success stories in cancer therapy of the past decade and results in remission of a high fraction of patients with CML.33 However, IM has also been shown to cause unanticipated cardiotoxicity reported as a decline in LV ejection fraction and congestive heart failure in patients without any prior history of heart disease.5, 34, 35 Extensive animal studies have reinforced these findings.5, 36, 37 The association between kinase inhibitors and cardiotoxicity has prompted the need to develop a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying kinase inhibitor‐induced cardiotoxicity.

To date, there is not much known about the mechanisms of toxicity associated with kinase inhibitors that lead to cardiac dysfunction. Electron microscopic analysis of heart biopsy specimens from patients taking imatinib showed nonspecific abnormalities in mitochondria and cytosolic vacuoles containing membranous debris.5 Studies in cultured cardiomyocytes showed that IM leads to significant mitochondrial dysfunction with loss of membrane potential, release of cytochrome c, and markedly impaired energy generation with significant declines in ATP concentration which was associated with cell death that morphologically resembled necrosis (cytosolic vacuolization, loss of cell membrane integrity, and lack of caspase‐3 activation).5 Mitochondrial defects have also been seen in patients treated with other TKIs38, 39 who also developed heart failure characterized by myocyte hypertrophy.38

The goals of the present study were to further define the effects of chronic, in vitro IM treatment on cardiac myocyte function, hypertrophy, and survival. Our experiments show that IM treatment enhanced Ca2+ transients of cardiac myocytes, induced pathological hypertrophy, and, at high doses, and caused myocyte death. The cellular bases of these effects were explored throughout our study.

IM and myocyte Ca2± transients

Intracellular Ca2+ plays a vital role in many physiological and pathophysiological processes in cardiomycoytes. Altered intracellular Ca2+ handling and impaired Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiomyocytes has been implicated in drug‐induced cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenesis and may serve as a unifying theme in clinically observed cardiotoxic events.40, 41 Our experiments showed that myocytes that had chronic IM treatment had a dose dependent increase in their Ca2+ transients and the transients were shorter than normal duration with a faster rate of decay (Figure 1 ). It does not appear that this resulted from an acute, direct effect of IM on L‐type Ca2+ current, since this current was not altered by acute or chronic IM exposure (not shown). However, after exposing NRVMs to IM for 72 hours, their systolic Ca2+ transients were increased in peak amplitude and the rate of decline was accelerated.

Molecular remodeling was studied in IM‐treated myocytes. There was a dose dependent increase in the abundance of the NCX, the major Ca2+ efflux pathway in the heart,42 suggesting that NCX activity is increased to ensure Ca2+ flux balance in the presence of the increased Ca2+ transient amplitude (Figure 2 A and B). We also observed significant changes in CaMKII mediated PLB‐T17 and RyR‐S2814 phosphorylation (Figure 2 C and D), which contributes to enhanced SR Ca2+ uptake, storage, and release.43 These results are somewhat surprising, since IM treatment in cancer patients has been linked to reduced cardiac pump function.32 As we will discuss in more detail below, contractile defects in these patients may in part be due to necrotic cell death and loss of myocardial mass rather than by direct effects of altered Ca2+ regulatory proteins and Ca2+ cycling dynamics.

IM and myocyte hypertrophy

Impaired cardiac function in humans and mice treated with IM has been reported and previous studies have shown evidence of cardiac hypertrophy in these subjects characterized by elevated levels of BNP at both the mRNA and protein levels.6, 44 We examined myocyte hypertrophy in our in vitro studies and found that IM treatment caused an increase in cell volume at low doses and no change in average cell volume at higher doses (Figure 3 C). We also found that IM treatment caused a dose dependent increase in the expression of the hypertrophy marker ANP (Figure 3 A). We had already shown that CaMKII activation was at least partially responsible for IM treatment‐induced changes in myocyte contractility. Therefore, we also determined if IM treatment‐induced hypertrophy also involved CaMKII activation. Our experiments showed that myocytes treated with the CaMKII inhibitor AIP, or infected with a virus containing a dn‐CaMKII had less IM treatment‐induced hypertrophy and expression of ANP (Figure 5). Our experiments also showed that the hypertrophy induced by IM treatment involved activation of Cn‐NFAT signaling. IM treatment‐induced nuclear translocation of NFAT (Figure 6) and this effect was blocked by the Cn inhibitor FK506, the CaMKII inhibitor AIP, and by the LTCC blocker Nifedipine. Collectively these data suggest that IM treatment increases the pool of cellular Ca2+ that activates CaMKII and Cn‐NFAT nuclear translocation, to increase myocyte contractions and induce pathological hypertrophy.

IM and myocyte death

It remains unclear whether LV dysfunction with TKIs is attributable to myocyte loss (and therefore largely irreversible) or myocyte dysfunction (potentially irreversible). IM caused a dose dependent increase in myocyte death, as shown by a reduced number of myocytes per dish. However, we did not see an activation of the apoptosis activator Caspase 3 (Figure 4), suggesting that the myocytes were not dying via programmed apoptosis, but rather through necrotic cell death. This finding is in accordance with literature that describes a striking loss of myocardial mass in mice treated with IM that was consistent with cell loss and characterized by morphological hallmarks of necrotic cell death in histological heart sections.5 Previously, our laboratory has shown that myocytes with chronic increases in [Ca2+] die of a form of regulated necrosis rather than via apoptosis, and we suggest that this mechanism must be present in IM treated myocytes.45

Conclusion

These studies show that chronic IM treatment of cardiomyocytes in vitro causes alterations in Ca2+ transients, cardiac hypertrophy, and cell death at high IM doses. These findings suggest that chronic IM therapy has the potential to cause a hypertrophy and cell death based cardiomyopathy resulting from chronic Ca2+ stress. If patients have some underlying cardiac disease, these effects might occur at lower IM doses. Our data suggest that chronic IM therapy could cause cardiotoxic effects through Ca2+ dysregulation and the induction of necrotic cell death and these findings provide important insights into the evolving field of off‐target effects of cancer therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants to SRH (R01HL089312, T32HL091804, P01HL091799, and R37HL033921) and TF (R01HL06168817 and R01HL11412402).

References

- 1. Van Etten RA. Mechanisms of transformation by the Bcr‐Abl oncogene: new perspectives in the post‐imatinib era. Leuk Res. 2004; 28(Suppl. 1): 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Quintas‐Cardama A, Cortes J. Important therapeutic targets in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2007; 13: 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chu S, Xu H, Shah NP, Snyder DS, Forman SJ, Sawyers CL, Bhatia R. Detection of Bcr‐Abl kinase mutations in CD34+ cells from chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission on imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood. 2005; 105: 2093–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deininger M, Buchdunger E, Druker BJ. The development of imatinib as a therapeutic agent for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005; 105: 2640–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kerkela R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, Walters B, Shevtsov S, Pesant S, Clubb FJ, et al. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nat Med. 2006; 12: 908–‐916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park YH, Park HJ, Kim BS, Ha E, Jung KH, Yoon SH, Yim SV, Chung JH. BNP as a marker of the heart failure in the treatment of imatinib mesylate. Cancer Lett. 2006; 243: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alihanoglu YI, Kaya Z, Ari H, Karaarslan S, Yildiz BS, Karanfil M, Yazici M, Boruban MC, Ozdemir K, Ulgen MS. Assessment of left ventricular systolic and diastolic function with conventional and tissue Doppler echocardiography imaging techniques in patients administered tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2012; 40: 597–‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wolff NC, Ilaria RL, Jr . Establishment of a murine model for therapy‐treated chronic myelogenous leukemia using the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571. Blood. 2001; 98: 2808–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. von Haehling S, Lainscak M, Springer J, Anker SD. Cardiac cachexia: a systematic overview. Pharmacol Ther. 2009; 121: 227–‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Larson RA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, Riviere GJ, Krahnke T, Gathmann I, Wang Y. Imatinib pharmacokinetics and its correlation with response and safety in chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a subanalysis of the iris study. Blood. 2008; 111: 4022–4028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Picard S, Titier K, Etienne G, Teilhet E, Ducint D, Bernard MA, Lassalle R, Marit G, Reiffers J, Begaud B, et al. Trough imatinib plasma levels are associated with both cytogenetic and molecular responses to standard‐dose imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007; 109: 3496–3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishikimi T, Maeda N, Matsuoka H. The role of natriuretic peptides in cardioprotection. Cardiovas Res. 2006; 69: 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mills GD, Kubo H, Harris DM, Berretta RM, Piacentino V, 3rd , Houser SR. Phosphorylation of phospholamban at threonine‐17 reduces cardiac adrenergic contractile responsiveness in chronic pressure overload‐induced hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006; 291: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Molkentin JD, Lu JR, Antos CL, Markham B, Richardson J, Robbins J, Grant SR, Olson EN. A calcineurin‐dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998; 93: 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Calcium‐calcineurin signaling in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004; 322: 1178–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao H, Wang F, Wang W, Makarewich CA, Zhang H, Kubo H, Berretta RM, Barr LA, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. Ca2+ influx through l‐type Ca2+ channels and transient receptor potential channels activates pathological hypertrophy signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012; 53: 657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaughan JP, Hefner CA, Houser SR. Electrophysiological properties of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes with alpha1‐adrenergic‐induced hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1998; 275: 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simpson P, Savion S. Differentiation of rat myocytes in single cell cultures with and without proliferating nonmyocardial cells. Cross‐striations, ultrastructure, and chronotropic response to isoproterenol. Circ Res. 1982; 50: 101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, Kottom TJ, Murphy SJ, Limper AH, Leof EB. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF‐beta and prevents bleomycin‐mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004; 114: 1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang H, Makarewich CA, Kubo H, Wang W, Duran JM, Li Y, Berretta RM, Koch WJ, Chen X, Gao E, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor at serine 2808 is not involved in cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012; 110: 831–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alibin CP, Kopilas MA, Anderson HD. Suppression of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy by conjugated linoleic acid: role of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors alpha and gamma. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 10707–10715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson HD, Wang F, Gardner DG. Role of the epidermal growth factor receptor in signaling strain‐dependent activation of the brain natriuretic peptide gene. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 9287–9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silver LH, Hemwall EL, Marino TA, Houser SR. Isolation and morphology of calcium‐tolerant feline ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1983; 245: 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohtsu H, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Brailoiu E, Higuchi S, Suzuki H, Nakashima H, Eguchi K, Eguchi S. Adam17 mediates epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006; 26: 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Makarewich CA, Correll RN, Gao H, Zhang H, Yang B, Berretta RM, Rizzo V, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. A caveolae‐targeted l‐type Ca2+ channel antagonist inhibits hypertrophic signaling without reducing cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 2012; 110: 669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X, Wilson RM, Kubo H, Berretta RM, Harris DM, Zhang X, Jaleel N, MacDonnell SM, Bearzi C, Tillmanns J, et al. Adolescent feline heart contains a population of small, proliferative ventricular myocytes with immature physiological properties. Circ Res. 2007; 100: 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kubo H, Margulies KB, Piacentino V, 3rd, Gaughan JP, Houser SR. Patients with end‐stage congestive heart failure treated with beta‐adrenergic receptor antagonists have improved ventricular myocyte calcium regulatory protein abundance. Circulation. 2001; 104: 1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Molkentin JD. Calcineurin and beyond: cardiac hypertrophic signaling. Circ Res. 2000; 87: 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fernandes‐Alnemri T, Litwack G, Alnemri ES. CPP32, a novel human apoptotic protein with homology to caenorhabditis elegans cell death protein ced‐3 and mammalian interleukin‐1 beta‐converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269: 30761–30764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang T, Kohlhaas M, Backs J, Mishra S, Phillips W, Dybkova N, Chang S, Ling H, Bers DM, Maier LS, et al. CamkIIdelta isoforms differentially affect calcium handling but similarly regulate HDAC/MEF2 transcriptional responses. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282: 35078–35087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacDonnell SM, Weisser‐Thomas J, Kubo H, Hanscome M, Liu Q, Jaleel N, Berretta R, Chen X, Brown JH, Sabri AK, et al. CaMKII negatively regulates calcineurin‐NFAT signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009; 105: 316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng H, Force T. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular toxicity of targeted cancer therapeutics. Circ Res. 2010; 106: 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marchan R, Bolt HM. Imatinib: the controversial discussion on cardiotoxicity induced by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Arch Toxicol. 2012; 86: 339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Force T, Kerkela R. Cardiotoxicity of the new cancer therapeutics–mechanisms of, and approaches to, the problem. Drug Discov Today. 2008; 13: 778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Force T, Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007; 7: 332–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saad SY, Alkharfy KM, Arafah MM. Cardiotoxic effects of arsenic trioxide/imatinib mesilate combination in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006; 58: 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herman EH, Knapton A, Rosen E, Thompson K, Rosenzweig B, Estis J, Agee S, Lu QA, Todd JA, Lipshultz S, et al. A multifaceted evaluation of imatinib‐induced cardiotoxicity in the rat. Toxicol Pathol. 2011; 39: 1091–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, Dallabrida SM, Zurakowski D, Nguyen L, Woulfe K, Pravda E, Cassiola F, Desai J, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007; 370: 2011–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Will Y, Dykens JA, Nadanaciva S, Hirakawa B, Jamieson J, Marroquin LD, Hynes J, Patyna S, Jessen BA. Effect of the multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib, dasatinib, sunitinib, and sorafenib on mitochondrial function in isolated rat heart mitochondria and H9c2 cells. Toxicol Sci. 2008; 106: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999; 42: 270–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Janse MJ. Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovas Res. 2004; 61: 208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weber CR, Ginsburg KS, Philipson KD, Shannon TR, Bers DM. Allosteric regulation of Na/Ca exchange current by cytosolic Ca in intact cardiac myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2001; 117: 119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grimm M, Brown JH. Beta‐adrenergic receptor signaling in the heart: role of CamkII. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010; 48: 322–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fernandez A, Sanguino A, Peng Z, Ozturk E, Chen J, Crespo A, Wulf S, Shavrin A, Qin C, Ma J, et al. An anticancer C‐Kit kinase inhibitor is reengineered to make it more active and less cardiotoxic. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117: 4044–4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nakayama H, Chen X, Baines CP, Klevitsky R, Zhang X, Zhang H, Jaleel N, Chua BH, Hewett TE, Robbins J, et al. Ca2+‐ and mitochondrial‐dependent cardiomyocyte necrosis as a primary mediator of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117: 2431–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]