SUMMARY

In Escherichia coli, initial assembly of the Z ring for cell division requires FtsZ plus the essential Z ring-associated proteins FtsA and ZipA. Thermosensitive mutations in ftsA, such as ftsA27, map in or near its ATP binding pocket and result in cell division arrest at nonpermissive temperatures. We found that purified wild-type FtsA bound and hydrolyzed ATP, whereas FtsA27 was defective in both activities. FtsA27 was also less able to localize to the Z ring in vivo. To investigate the role of ATP transactions in FtsA function in vivo, we isolated intragenic suppressors of ftsA27. Suppressor lesions in the ATP site restored the ability of FtsA27 to compete with ZipA at the Z ring, and enhanced ATP binding and hydrolysis in vitro. Notably, suppressors outside of the ATP binding site, including some mapping to the FtsA-FtsA subunit interface, also enhanced ATP transactions and exhibited gain of function phenotypes in vivo. These results suggest that allosteric effects, including changes in oligomeric state, may influence the ability of FtsA to bind and/or hydrolyze ATP.

INTRODUCTION

In the model organism Escherichia coli, the highly conserved tubulin homolog FtsZ assembles into the cytokinetic ring (Z ring) at midcell (Bi and Lutkenhaus, 1991). Two additional proteins, FtsA and ZipA, are both essential for cell division and work together to anchor the Z ring to the cytoplasmic membrane (Hernández-Rocamora et al., 2012; Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2002). Both proteins bind to the carboxy-terminal tail of FtsZ (Din et al., 1998; Hale et al., 2000; Liu et al., 1999; Ma and Margolin, 1999; Moreira et al., 2006; Mosyak et al., 2000; Shen and Lutkenhaus, 2009; Szwedziak et al., 2012), and both are required for the maturation of the Z ring, including recruitment of downstream cell division proteins (Busiek and Margolin, 2014; Busiek et al., 2012; Corbin et al., 2004; Hale and de Boer, 2002; Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2002; Rico et al., 2004).

In addition to anchoring the Z ring to the cytoplasmic membrane and recruiting downstream proteins, ZipA has been shown to be important for stabilizing the Z ring and is required for the FtsZ-dependent formation of preseptal peptidoglycan (Kuchibhatla et al., 2011; Pazos et al., 2013; Potluri et al., 2012; RayChaudhuri, 1999). ZipA also promotes bundling of FtsZ protofilaments in vitro (Hale et al., 2000; RayChaudhuri, 1999). However, zipA is only conserved among the gamma-proteobacteria (Margolin, 2000), and no evidence currently exists for direct recruitment of downstream cell division proteins by ZipA. In addition, a number of point mutations in ftsA allow a complete bypass of zipA (Geissler et al., 2003; Pichoff et al., 2012). This has led to the hypothesis that FtsA is the dominant Z ring anchor required for septation.

FtsA is almost as widely conserved in bacteria as FtsZ (Margolin, 2000). FtsA belongs to the actin, HSP70, sugar kinase superfamily of ATPases, and maintains a structural homology to actin with the exception of one of its four subdomains (Bork et al., 1992; van den Ent and Löwe, 2000). Each subdomain plays a role in FtsA self-interaction, with the FtsA-FtsA subunit interface defined in the atomic structure of an oligomer (Szwedziak et al., 2012). Subdomains 1A, 2A and 2B make up the conserved ATP binding pocket (van den Ent and Löwe, 2000). Subdomain 2B also contains the residues required for interaction with FtsZ (Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2007). The unique subdomain 1C interacts directly with downstream division proteins (Busiek et al., 2012; Corbin et al., 2004; Rico et al., 2004). With all of these functions, FtsA is not only a membrane anchor for the Z ring, but also is probably a key regulator of bacterial cell division.

Recent evidence supports the idea that FtsA regulates the Z ring. In 2009, we showed that the FtsA hypermorph, FtsA-R286W, also known as FtsA*, can curve and shorten FtsZ polymers in vitro in the presence of ATP (Beuria et al., 2009). This led us to hypothesize that FtsA must bind and/or hydrolyze ATP to regulate FtsZ assembly and Z ring dynamics. There have been reports of FtsA from Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa having measurable ATPase activity (Feucht et al., 2001; Paradis-Bleau et al., 2005), but the role of ATPase activity in FtsA function or what stimulates it remain unknown. Little progress has been made in deciphering how ATP influences FtsA activity because of the need to refold FtsA from insoluble inclusion bodies (Martos et al., 2012; Paradis-Bleau et al., 2005). However, Loose and Mitchison very recently had success in isolating soluble active E. coli FtsA and reported that ATP is required for FtsA to interact with FtsZ in a supported lipid bilayer system (Loose and Mitchison, 2014).

To investigate the role of ATP binding by FtsA in vivo, we took advantage of an ftsA thermosensitive (ts) allele. Other known FtsA lesions at the ATP binding site, such as FtsA-G336D, confer complete loss of function in vivo, making them recalcitrant to analysis. The advantage of ts mutants is that they allow mostly normal cell division at 30°C and thus their function can be switched off by shifting to the non-permissive temperature (42°C), facilitating in vivo studies. Our ability to purify FtsA in soluble form allows complementary biochemical analyses, such as nucleotide binding measurements. In this study, we investigate a previously uncharacterized ts mutant, ftsA27 (S195P) and some thermoresistant intragenic suppressors. In addition, we further characterize the biochemical properties of wild-type (WT) FtsA and FtsA*.

RESULTS

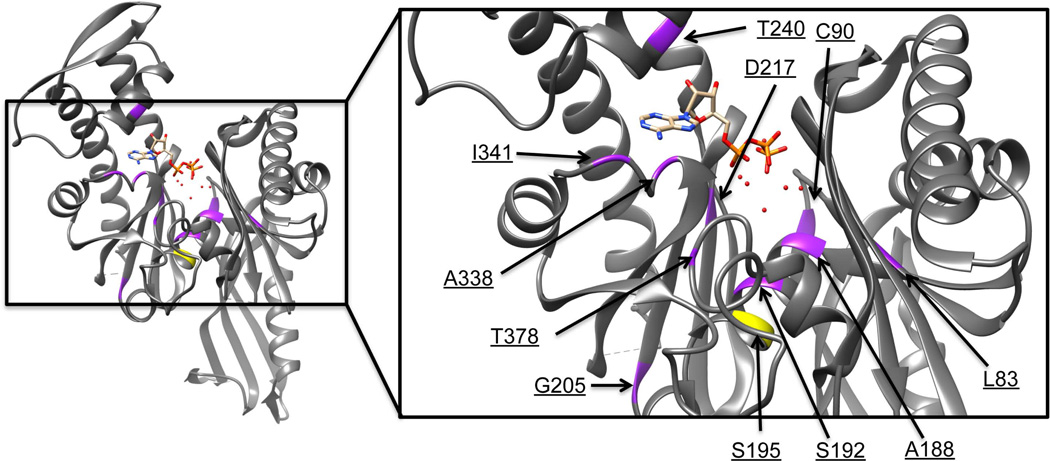

Thermosensitive alleles of E. coli ftsA map to residues in or adjacent to the ATP binding site

As a first step to understand the mechanism behind the thermosensitivity of E. coli ftsA alleles, we mapped the mutations in ftsA12, ftsA27 and ftsA1882, which have been used to conditionally inhibit FtsA function. We found that the proteins encoded by ftsA12, ftsA27 and ftsA1882 had the amino acid changes A188V, S195P, and T378M, respectively. A188 corresponds to S190 of the crystallized Thermotoga maritima FtsA, which is located at the beginning of helix H4 and identified as an active site residue (van den Ent and Löwe, 2000). S195 corresponds to T. maritima G197, at the end of H4 and not in the active site, but in the Mg++ binding site. T378 corresponds to T. maritima D383, on helix H11 near the α phosphate of ATP. Each is in the ATP binding pocket of FtsA as defined by the T. maritima FtsA crystal structure. Interestingly, all other published ftsA (ts) mutant alleles are dispersed along the primary sequence but are also within or adjacent to the ATP binding pocket of the tertiary structure of FtsA (Table 1 and Figure 1) (Robinson et al., 1988, 1991; Sanchez et al., 1994). This suggests that there are many lesions that can render FtsA thermosensitive, but they probably all share defects in ATP binding and/or hydrolysis.

Table 1. All sequenced temperature-sensitive ftsA mutants map to the active site.

| FtsA(ts) Mutant Protein |

Identity & Location of Lesion |

|---|---|

| FtsA8-25 | L83F in S4 near the γ phosphate (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| FtsA22 | C90W in S5 near the γ phosphate (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| FtsA12 | A188V in H4 in the Mg++ binding pocket (this work) |

| FtsA40 | S192L in H4 in the Mg++ binding pocket (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| FtsA27 | S195P in H4 in the Mg++ binding pocket (this work) |

| FtsA38/21 | G205S between H5 & S9 – Mg++ binding, phosphate binding/hydrolysis (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| FtsA6 | D217N in S10, predicted to be involved in ATP hydrolysis (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| FtsA3 | T240I in H6 in the adenosine binding pocket (Sanchez et al., 1994) |

| FtsA2 | A338T between S14 & H9 in the adenosine binding pocket (Sanchez et al., 1994) |

| FtsA13 | I341N between H9 & H10 in the adenosine binding pocket (Robinson et al., 1991) |

| FtsA1882 | T378M in H11 near the α-phosphate of ATP (this work) |

FIG. 1. Thermosensitive mutations of ftsA map to the ATP-binding site.

A structure of FtsA from T. maritima with a magnified region highlighting locations of lesions that render E. coli FtsA thermosensitive highlighted in yellow (S195P, encoded by ftsA27 and the focus of this study) or purple (all other known lesions). Water molecules are denoted by red dots.

Intragenic suppressors of ftsA27 map to the ATP binding site and elsewhere including the putative FtsA dimer interface

It was shown previously that FtsA27 localization at division sites is lost within 30 minutes of shifting the cells to 42°C, but the protein remained relatively stable and Z rings remained intact (Addinall et al., 1996). This suggested that FtsA27 loses its interaction with the Z ring upon temperature shift. We confirmed these observations (Figure S1A), and further showed that the delocalization occurred as soon as 5 min after the temperature shift in essentially all (97%) of the cells counted (Figure S1B and data not shown). WT FtsA rings were present in most cells under these conditions (Figure S1B). As FtsA depends upon FtsZ for its localization to the Z ring, these results suggest that FtsA-FtsZ interactions were rapidly destabilized by the shift.

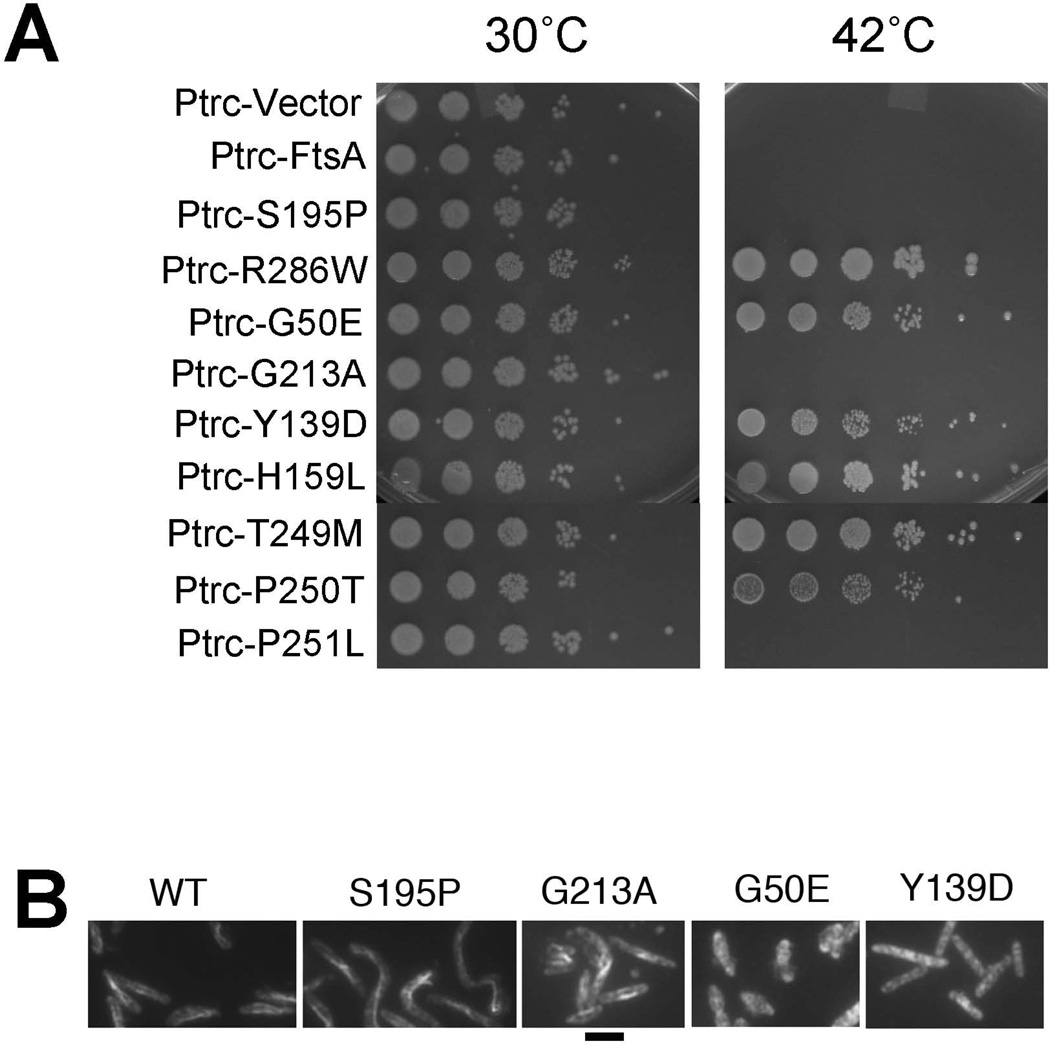

To understand more about how FtsA-FtsZ interactions are affected by thermoinactivation of FtsA27, we selected thermoresistant spontaneous suppressors of ftsA27 by plating serial dilutions of each strain at 42°C (see Experimental Procedures). Aside from the expected revertants, we obtained multiple intragenic suppressors. These were identified as single point mutations that were able to suppress the temperature sensitivity of S195P in cis (Figure 2A). When isolated from the S195P lesion and expressed from an IPTG-inducible trc promoter on plasmid pWM2784, these individual suppressor alleles were able to support viability in a strain containing an ftsA null allele (Figure S2).

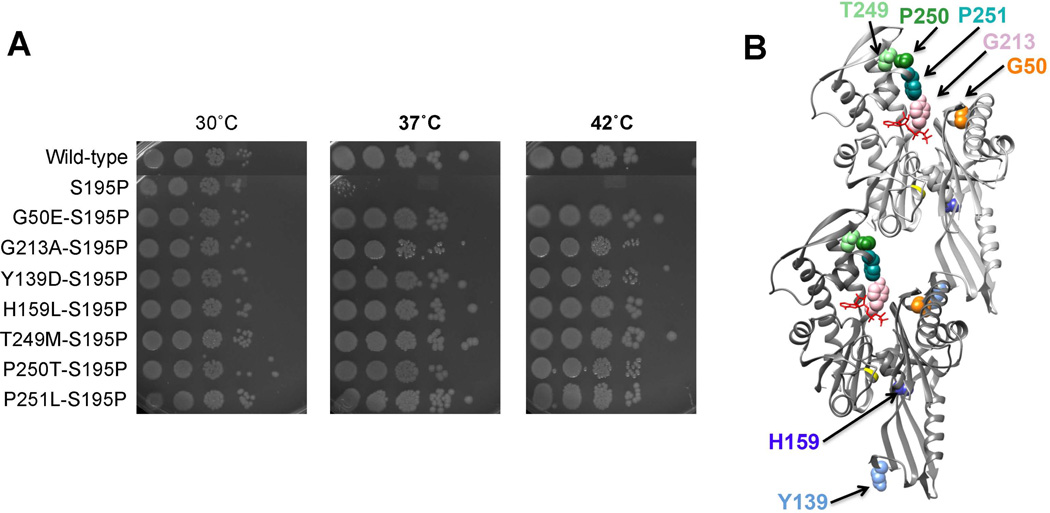

FIG. 2. Intragenic suppressors of ftsA27 restore thermoresistance and map to different regions of FtsA.

A) Serial dilution growth assay of WT E. coli and cells expressing chromosomal ftsA27 or an intragenic suppressor of ftsA27 spotted on plates incubated at the indicated temperatures. B) Locations of the intragenic suppressor mutations on the dimer structure of T. maritima FtsA.

We expected that the intragenic suppressors might map to the ATP binding pocket, compensating for the original lesion. Indeed, one suppressor mutation, G213A, is consistent with this idea. G213 corresponds to Y215 in T. maritima and is predicted to make contacts with the alpha, beta and gamma phosphates of ATP (van den Ent and Löwe, 2000). However, additional suppressors mapped outside the ATP binding pocket.

G50E, in subdomain 1A, and Y139D, in subdomain 1C, were located at or near the proposed FtsA-FtsA interface (Figure 2B), with G50E at the top of one subunit and Y139D at the bottom of a corresponding subunit. Another mutation, H159L, was located within subdomain 1C but not near any known binding interface (Figure 2B). The other three suppressor mutations were in three consecutive residues within subdomain 2B: T249M, P250T and P251L. These residues are near the FtsA-FtsA interface, but also near the ATP binding pocket (Figure 2B).

Increased sensitivity of FtsA27 to ZipA overproduction at the permissive temperature suggests a weaker interaction with the Z ring

The rapid delocalization of FtsA27 from the Z ring after the temperature shift to 42°C (Figure S1A) suggests that the mutant protein may be defective in interacting with FtsZ, despite having no lesions in the FtsZ-interacting domain. Because the lesion is near the ATP binding site, this idea is consistent with previous findings which suggest that FtsA must bind to ATP to interact with FtsZ (Beuria et al., 2009; Loose and Mitchison, 2014; Osawa and Erickson, 2013). To explore whether a lesion in the ATP binding pocket affects FtsA-FtsZ interactions in vivo, we exploited the idea that ZipA and FtsA should compete for binding to the same conserved segment of the carboxy-terminus of FtsZ.

Like overproduction of FtsA, overproduction of ZipA is toxic to E. coli, causing strong inhibition of cell division (Hale and de Boer, 1997). Although massive overproduction of ZipA can cause significant membrane disturbances and recruit FtsZ away from the division site (Cabré et al. 2013), moderate excess of ZipA might preserve Z rings but prevent FtsA from interacting with FtsZ. This seems reasonable, as ZipA seems to bind to the FtsZ C-terminal tail more strongly than does FtsA in vivo (Shen and Lutkenhaus, 2009), and the original search for FtsZ interacting proteins identified ZipA but not FtsA (Hale and de Boer, 1997).

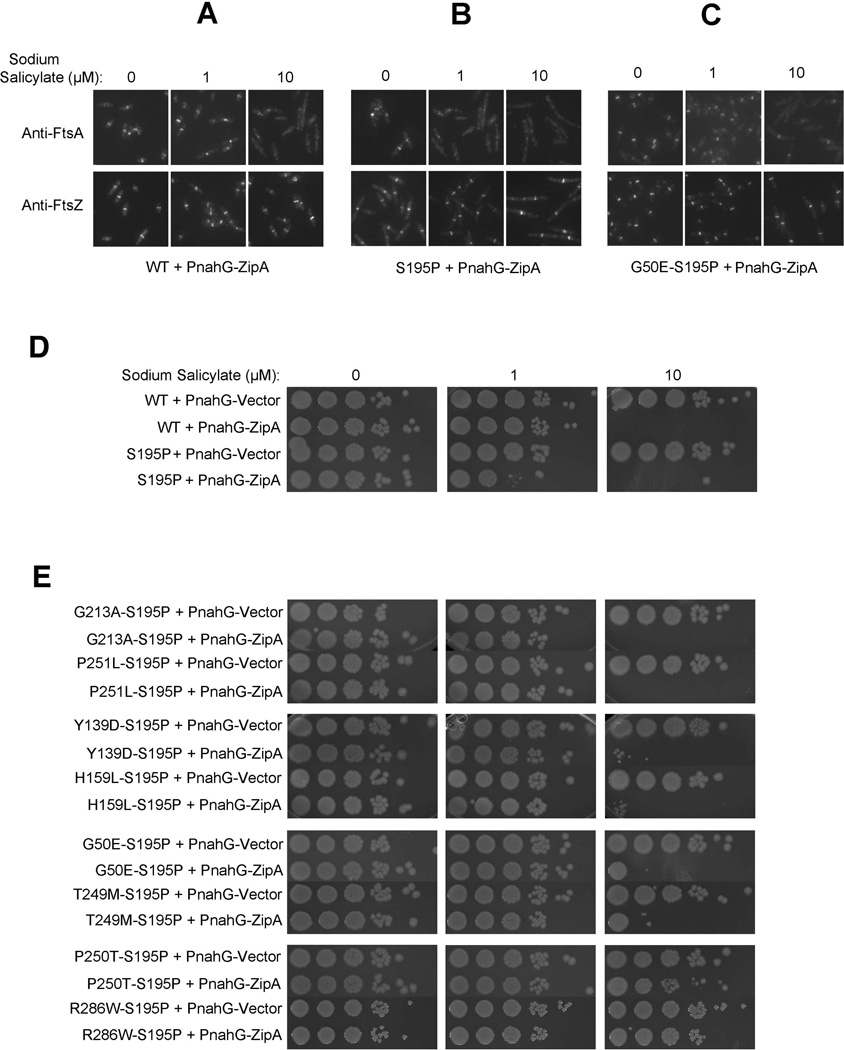

To determine if ZipA indeed competes with FtsA for binding to the Z ring, we overproduced ZipA in WT cells and measured FtsA localization by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM). We used a sodium salicylate-inducible promoter (PnahR) to drive zipA expression on a plasmid (pWM3073) in a merodiploid strain, expecting that FtsA would delocalize at higher ZipA concentrations. At uninduced or low levels (1 µM) of salicylate, FtsA remained localized to Z rings (Fig. 3A) and displayed normal viability (Fig. 3D). However, at 10 µM salicylate, FtsA localization at midcell decreased dramatically, suggesting that FtsA was competed away from the Z ring although FtsZ localization was unaffected (Figure 3A). Consistent with this, there was normal growth on plates containing 0 or 1 µM salicylate but none at 10 µM (Fig. 3D). These data strongly suggest that FtsA cannot bind to the Z ring in the presence of high levels of ZipA.

FIG. 3. Resistance of ftsA27 and ftsA27 suppressors to overproduced ZipA.

A–C) IFM images showing localization of FtsA or FtsZ in cells with WT chromosomal ftsA (A) ftsA27 (encoding S195P) (B) or the suppressor encoding G50E S195P (C), containing zipA expressed from a sodium salicylate-inducible plasmid at three concentrations of inducer. Scale bars are 2 µm. D) Serial dilution growth assay of WT and ftsA27 cells containing zipA expressed from a sodium salicylate-inducible plasmid, under the indicated inducer concentrations. E) Growth assay performed as described in B, with ftsA27 suppressor cells. Growth assays from different plates are shown as composite images.

We then reasoned that any FtsA that had stronger interactions with FtsZ should be more resistant to ZipA overproduction, whereas FtsA mutants with weaker binding to FtsZ should be even more sensitive. All assays were done at 30°C, where FtsA27 (S195P) localizes normally to Z rings. With no induction of extra zipA, ftsA27 cells grew normally in serial dilution plate assays and exhibited normal FtsA rings, indicating that these levels of ZipA were not inhibitory (Figure 3B, D). However, in contrast to WT cells, even a low level of zipA induction (1 µM sodium salicylate) was toxic to ftsA27 cells, which displayed >10-fold lower plating efficiency and lost FtsA localization at the Z ring (Figure 3B, D). High levels of inducer (10 µM) were lethal to ftsA27 strains, with no FtsA localization to Z rings and no viability (Figure 3B, D). Figure S3 shows that ZipA was overproduced to approximately the same levels in each strain background. These results are consistent with the idea that FtsA27 delocalizes from the Z ring at high temperature because of an already weakened interaction with FtsZ, possibly caused by defects in binding or hydrolyzing ATP.

Two independent in vivo assays reveal that some FtsA27 suppressors have stronger affinity for the Z ring than WT FtsA

If the primary reason for the FtsA27 defect is a problem in interacting with FtsZ, then we predicted that the suppressors should correct this, possibly even at the permissive temperature. In support of this, the ftsA27 suppressor strains containing both the S195 lesion and a suppressor lesion restored resistance to low levels of zipA overexpression, even at 30°C (1 µM salicylate, Figure 3E). Strikingly, several of these double mutants conferred resistance to higher levels of zipA overexpression (10 µM sodium salicylate) that were toxic to cells with WT ftsA (Figure 3E). These included, in decreasing order of resistance, P250T, T249M, G50E, H159L, Y139D, and lastly P251L and G213A. In support of these viability data, we confirmed that the FtsA27 suppressor (G50E-S195P) localized to ~20% of Z rings at 10 µM salicylate (Fig. 3C), unlike FtsA27 alone, WT FtsA, or G213A-S195P (data not shown) which had no detectable localization. The H159L-S195P FtsA suppressor localized to ~10% of Z rings under the same conditions (data not shown), consistent with its lower viability than G50E-S195P but higher viability than the others upon ZipA overproduction. These results suggested that some FtsA27 suppressor proteins, despite having the S195P lesion on the same molecule, bind to the Z ring and probably FtsZ itself more strongly than does WT FtsA, conferring resistance to ZipA overproduction.

As the hypermorph FtsA* (R286W) shows several gain-of-function properties, including the ability to bypass ZipA as well as the ability to bind more strongly to FtsZ in yeast-two-hybrid assays (Geissler et al., 2003, 2007; Pichoff et al., 2012), we hypothesized that FtsA* also would confer increased resistance to ZipA overproduction. Using spot dilution assays, we observed that FtsA* indeed conferred resistance to the highest levels of ZipA overproduction that we tested (Figure 3C). These results corroborate the idea that resistance to ZipA is due to increased affinity of FtsA for FtsZ.

To lend further support to the idea that the suppressor lesions promote stronger FtsA-FtsZ interactions, we developed an independent genetic assay for measuring these interactions. FtsA contains a highly conserved arginine residue at position 300 that is required for binding to FtsZ (Szwedziak et al., 2012). Changing this residue to a glutamate, which has the opposite charge, completely abolishes FtsA binding to FtsZ by several criteria, as well as FtsA function in cell division (Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2007). Interestingly, moderate overproduction of R300E is significantly more toxic than WT FtsA at equivalent levels of protein (Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2007). This is also apparent in Figure 4 (compare rows 2 and 3, with FtsA and R300E at 0.1 mM IPTG). The postulated reason for this increased toxicity is that the R300E mutant protein effectively titrates later divisome proteins away from the Z ring whereas WT FtsA recruits them to the ring (Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2007).

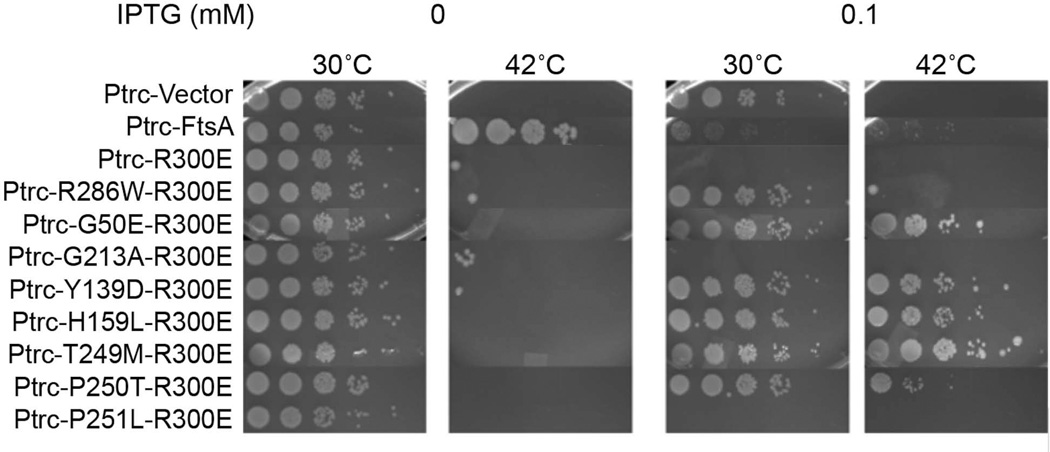

FIG. 4. Some mutations that suppress ftsA27 (S195P) also suppress R300E toxicity and loss of function.

Flag-ftsA alleles indicated were expressed from a plasmid with the IPTG-inducible trc promoter in WM1115 (ftsA12 (ts)) and grown in serial dilution spots at the indicated temperature with indicated amounts of IPTG. Growth assays from different plates are shown as composite images.

We surmised that mutations in FtsA that increased its resistance to competition by ZipA might exhibit increased affinity for FtsZ, and therefore could potentially restore some FtsZ binding activity to the R300E mutant. Such increased binding to FtsZ by R300E might result in reduced toxicity and potentially restoration of function. To test this idea, we combined the individual ftsA27 suppressor mutations with R300E in cis on a plasmid with the IPTG-inducible trc promoter (pWM2784) and measured toxicity upon induction with IPTG. Western blot analysis confirmed that each construct tested was produced at equivalent levels (data not shown). We used WM1115 (ftsA12 (ts)) as the strain background so that toxicity of the R300E derivatives could be tested at 30°C and their ability to complement tested at 42°C.

Without IPTG induction, all R300E derivatives grew normally at 30°C and failed to complement at 42°C (Figure 4). However, upon induction with 0.1 mM IPTG, the mutations that had suppressed ZipA toxicity, even weakly, also strongly suppressed R300E toxicity at 30°C (Figure 4; Figure S4). On the other hand, the weakest suppressors of ZipA toxicity, G213A and P251L, were unable to suppress R300E toxicity. Surprisingly, five of the six non-toxic R300E double mutants successfully complemented ftsA12 (ts) at 42°C to varying extents, indicating that these lesions restored function to FtsA proteins containing R300E. In contrast, FtsA* (R286W) could only partially complement R300E at even higher levels of induction (1 mM IPTG, data not shown), although it did suppress its toxicity at 30°C (Figure 4). Overproduction of the R300E double mutant constructs was needed for complementation, possibly because the R300E lesion may still inhibit binding to FtsZ, which can only be overcome by higher protein concentrations.

We conclude that some of the suppressors of ftsA27 can provide extra resistance to ZipA overproduction compared to WT ftsA and can complement an R300E mutant in cis. These results support the idea that residue changes outside the ATP binding pocket and, importantly, outside the known FtsA:FtsZ interface, can allosterically enhance FtsA’s interaction with FtsZ. Moreover, because the FtsA27 lesion is in the ATP binding site, these results further support the idea that FtsA needs ATP to interact efficiently with FtsZ in vivo.

Some suppressors of ftsA27 bypass the requirement for zipA

We noticed that some suppressors of ftsA27 were nearly identical (and one, T249M, was identical) to some of the mutants described by the Lutkenhaus group (Pichoff et al., 2012), which displayed decreased FtsA-FtsA interaction by two different in vivo assays and were able to bypass the requirement for the normally essential ZipA protein in cell division. We therefore hypothesized that our mutants might also bypass the requirement for ZipA. To test this, we attempted to transduce a ΔzipA::kan allele into the ftsA27 suppressor strains, as well as strains harboring plasmids containing the individual ftsA27 suppressor mutations without the S195P lesion in cis. Surprisingly, we were unable to obtain any transductants except from a strain expressing ftsA* (R286W), which was originally identified because of its ability to strongly bypass the zipA requirement (Geissler et al., 2003) and remains one of the strongest zipA bypass alleles of ftsA (Pichoff et al., 2012).

We expected that T249M would also bypass ZipA as shown previously, but because it did not we reasoned that this could be due to strain differences. The previous study used a W3110 strain background (Pichoff et al., 2012), whereas we used MG1655 for our analyses. To determine if strain background affected the ability to bypass zipA, we tested the ability of the individual ftsA27 suppressor alleles to suppress a zipA1 (ts) allele in a W3110 background (Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2002). As with our other constructs described above, these individual alleles (separated from ftsA27) were expressed from the IPTG inducible trc promoter on plasmid pWM2784. We found that G213A and P251L, which did not confer ZipA resistance beyond that of WT FtsA and could not complement an R300E mutation, also could not suppress the zipA1(ts) strain at 42°C. However, other suppressors of ftsA27 that conferred higher levels of ZipA resistance were able to suppress zipA1 (ts) (Figure 5A).

FIG. 5. Some mutations that suppress ftsA27 allow bypass of zipA and inhibit formation of cellular FtsAΔMTS polymers.

A) Serial dilution growth assay of indicated flag-ftsA alleles expressed from the IPTG inducible weak trc promoter on plasmids (uninduced) in a W3110 zipA1 (ts) background at indicated temperatures. Growth assays from different plates are shown as composite images. B) Presence or absence of cellular FtsA polymers after overproduction of several selected FtsA derivatives deleted for their C-terminal membrane targeting sequences. Overproduction of the FLAG-FtsA variants from the stronger trc promoter on pDSW208 was induced for 1 h with 0.1 mM IPTG; cells were then stained for FtsA and imaged by IFM. Scale bar = 2 µm.

To test if these alleles could bypass the complete loss of ZipA in a W3110 background, we transduced the ΔzipA::kan allele into the zipA1 (ts) strains exogenously expressing the ftsA27 suppressors (Figure S5). Intriguingly, the W3110 background allowed transduction of the ΔzipA::kan allele into some of the strains that expressed mutant ftsA alleles other than ftsA*. As expected, the strain expressing ftsA* (R286W) was able to robustly bypass the requirement for ZipA, whereas strains expressing the G213A or P251L alleles did not yield transductants, indicating they could not bypass ZipA. Strains expressing H159L, Y139D or P250T resulted in the smallest transductant colonies. In contrast, strains expressing T249M or G50E yielded slightly larger transductant colonies, indicating that they could bypass ZipA more robustly, however, the colonies were not as large as those from the strain expressing R286W. These results strongly suggest that W3110 is more permissive for bypassing ZipA than MG1655.

Genetic evidence that G50E and Y139D, but not G213A, disrupt FtsA-FtsA interactions

The presence of several of the suppressor lesions at or near the FtsA dimer interface suggested that they suppress the FtsA27 defect by perturbing FtsA-FtsA interactions. Such interactions have not yet been demonstrated biochemically, but genetic assays such as yeast two-hybrid, bacterial two-hybrid, and, most recently, FtsA polymer formation in vivo have been used in an attempt to measure these interactions. Visible assembly of FtsA polymers in cells occurs when the C-terminal 15 residues containing the membrane targeting sequence (MTS) is removed (Pichoff et al., 2012; Szwedziak et al., 2012)). Lesions that disrupt these polymers cluster near the dimer interface, suggesting that the in vivo polymers reflect increased FtsA dimerization.

As G50E and Y139D map to the dimer interface, while G213A maps to the ATP binding pocket, we tested which of these lesions would disrupt in vivo FtsA polymer formation. We constructed MTS deletion derivatives of these mutants, along with WT, R286W (which was previously shown to disrupt FtsAΔMTS polymers), and the original FtsA27 lesion S195P. As shown in Fig. 5B, overproduction of MTS-deleted FtsA assembled polymers in the majority of cells, as observed by IFM with anti-FtsA. Cells containing these FtsAΔMTS polymers curled and twisted dramatically, as observed previously (Gayda et al. 1992). Notably, G213A and S195P ΔMTS derivatives formed similar polymers (Figure 5B), indicating that the FtsA27 protein is capable of self-interaction and G213A does not significantly suppress this self-interaction. In contrast, the MTS-deleted G50E and Y139D derivatives displayed no FtsA polymers, even after prolonged overproduction, and did not curl the cells (Figure 5B). These data indirectly support the idea that G50E and Y139D, but not G213A, disrupt FtsA-FtsA interactions, and are consistent with the ZipA bypass results.

Purified FtsA27 is defective in binding ATP, but its suppressors restore ATP binding

To ascertain whether the decreased or increased binding to FtsZ correlated with a change in the ability of these FtsA proteins to bind ATP, we purified His6-tagged versions of wild type and mutant FtsA. We then measured their ability to bind ATP using a filter-binding assay with a fluorescent ATP analog. As predicted, based on the location of its lesion, FtsA27 (S195P) showed a dramatic reduction in its ability to bind ATP compared to WT FtsA (Table 2).

Table 2. ATP-binding properties of FtsA gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutants.

ATP binding was measured using technical replicates. All values were normalized to one of the WT replicates and averaged. Standard deviations are indicated.

| FtsA protein | Relative ATP binding |

|---|---|

| WT | 1.17 ± 0.15 |

| S195P (FtsA27) | 0.38 ± 0.26 |

| S195P-G213A | 1.33 ± 0.55 |

| S195P-G50E | 0.72 ± 0.18 |

| G213A | 5.94 ± 0.22 |

| G50E | 3.1 ± 1.10 |

| R286W (FtsA*) | 5.07 ± 0.90 |

We then tested two suppressors of ftsA27, FtsA-G50E-S195P and FtsA-G213A-S195P. These two mutants were chosen because they displayed different genetic phenotypes in our assays described above, and they are located in different domains of the protein. G50E is located at the FtsA-FtsA interface, provides extra resistance to ZipA overexpression, complements R300E in cis, and has the ability to bypass the requirement for ZipA. G213, on the other hand, is located in the ATP binding site and G213A does not show any gain-of-function compared to WT FtsA. We suspected that the G213A lesion would restore normal ATP binding to the FtsA27 protein by directly altering the conformation of the ATP binding site. However, we hypothesized that the G50E lesion could either allosterically restore ATP binding to FtsA27 or restore FtsA27 function solely via a distinct mechanism, such as reducing FtsA-FtsA interactions, which is suggested by its location on FtsA and its genetic similarity to T249M. As shown in Table 2, both the G213A and G50E mutations in cis with S195P restored ATP binding in vitro, although G213A enhanced ATP binding slightly more than G50E.

We then asked whether these lesions, when isolated from S195P in an otherwise WT protein, might exhibit hypermorphic properties. Table 2 shows that the G50E and G213A proteins had a drastically increased ability to bind to ATP, retaining 3–6 times more ATP on the filter than WT FtsA. We then asked whether FtsA* (R286W), like G50E and G213A, might bind ATP better than WT FtsA, because FtsA activity on FtsZ in vitro was not observed with WT FtsA but only with the FtsA* protein (Beuria et al., 2009; Osawa and Erickson, 2013). As predicted, purified FtsA* also showed a significant (~5-fold) increase in its ability to bind to ATP compared to WT FtsA.

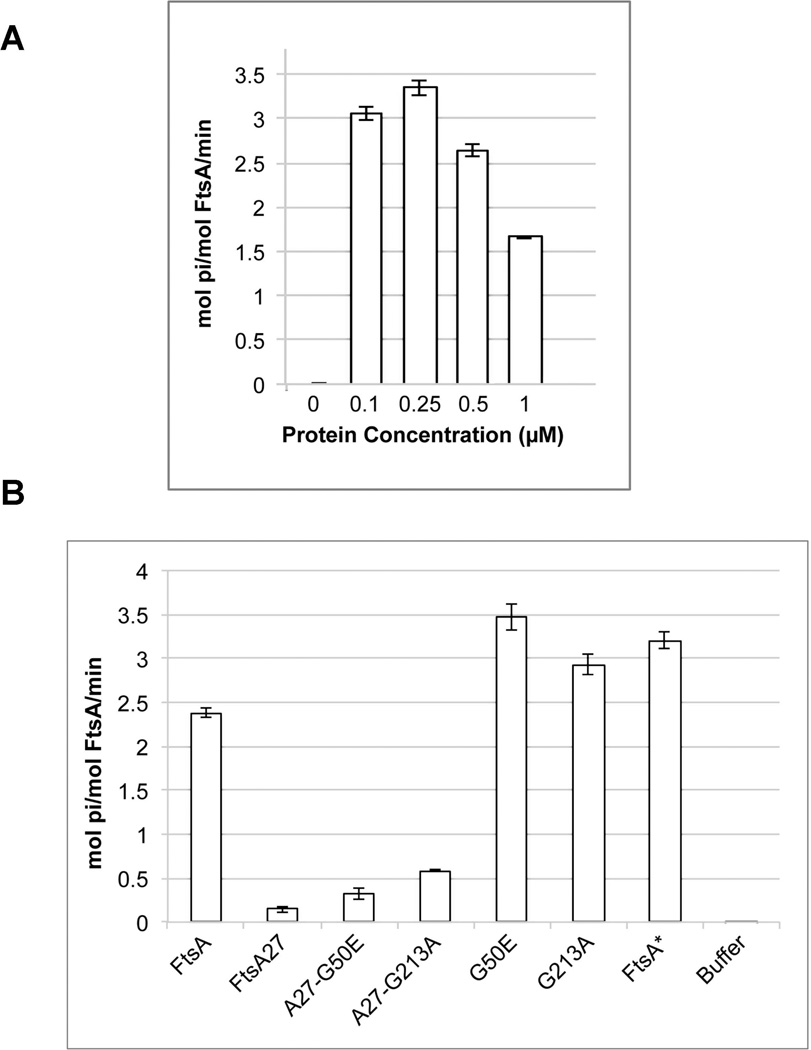

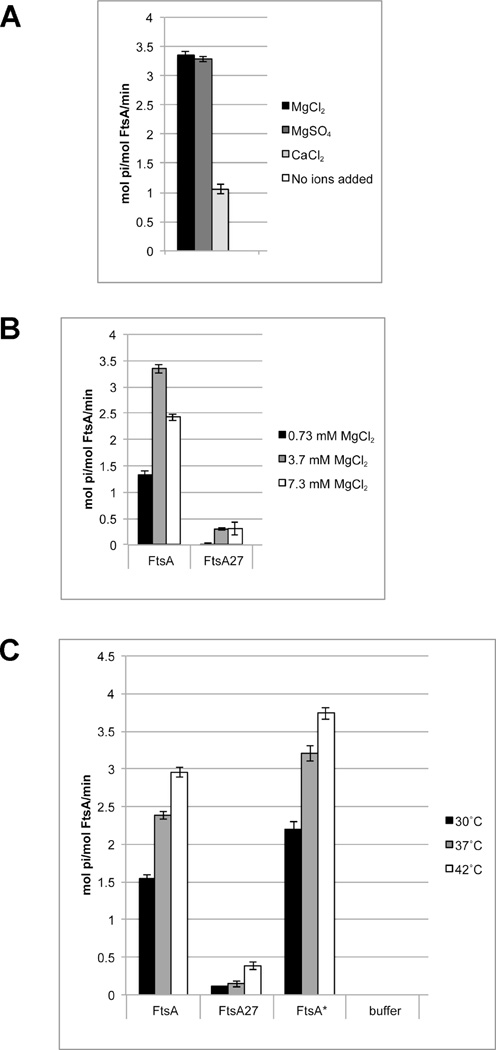

Purified E. coli FtsA can hydrolyze ATP

Given its ability to bind ATP, we then investigated whether our preparation of FtsA could hydrolyze ATP. After extensive optimization of protein purification (Figure S6) and assay conditions (described in Experimental Procedures) we were able to detect significant ATPase activity as measured by a sensitive phosphate release assay (Figures 6–7). Interestingly, we found that of the protein concentrations we tested, 0.25 µM His6-FtsA produced the highest ATPase activity, ~3 mol ATP/mol FtsA/min. When the protein concentration was increased to 0.5 or 1 µM, the specific ATPase activity decreased (Figure 6A), such that 1 µM His6-FtsA had about half the specific hydrolysis activity (~1.5 mol ATP hydrolyzed per mol FtsA per minute) of 0.25 µM FtsA. We also found that FtsA ATP hydrolysis required metal cations, with Mg++ preferred over Ca++ (Figure 7A). In addition, increasing Mg++ concentrations inhibited ATPase activity (Figure 7B) and ATPase activity increased with temperature, as expected (Figure 7B & C).

FIG. 6. Purified FtsA, FtsA27 and its suppressors display levels of ATPase activity that roughly correlate with their in vivo activities.

A) Rates of WT FtsA ATPase activity in 1 mM ATP with indicated amounts of FtsA protein. B) Rates of ATPase activity with 0.25 µM of indicated FtsA protein variant.

FIG. 7. Rates of FtsA ATPase activity depend on type and amount of Mg++ ions as well as temperature.

A) Rates of ATPase activity with WT FtsA in the presence of indicated metal ions. B) Rates of ATPase activity with WT FtsA and FtsA27 at the indicated concentrations of MgCl2. C) Rates of ATPase activity with the indicated FtsA protein at indicated temperatures. All reactions contained 0.25 µM protein.

Because ATP binding is a prerequisite for ATP hydrolysis, we reasoned that ATPase activity of our mutant proteins might correlate with the degree of ATP binding. As expected, the rate of hydrolysis from FtsA27 protein was extremely low, between 0.1 and 0.5 mol ATP/mol FtsA/min (Figure 6B, 7B–C). Although low, this was slightly higher than the spontaneous rate of ATP hydrolysis under the conditions we used. This indicates that FtsA27 may be able to bind low levels of ATP that could not be detected in our ATP binding assay, and that it can hydrolyze this low amount of ATP. Interestingly, the FtsA27 suppressor proteins FtsA-G213A-S195P and FtsA-G50E-S195P showed an increase in ATPase activity compared to FtsA-S195P alone, but the levels were still significantly lower than WT levels (Figure 6B). Because proteins with the individual residue changes R286W, G50E and G213A (separated from S195P) displayed 3–6 times more ATP binding than the WT protein, we thought we would detect a similar increase in the rates of hydrolysis. Although we did observe an increase, it was only about 1.5 times greater than the rate of ATP hydrolysis from the WT protein (Figure 6B).

Our data show that ATP binding by the various mutants roughly parallels ATP hydrolysis. Despite binding to ATP as efficiently as WT FtsA, G213A-S195P and G50E-S195P display very low levels of ATP hydrolysis, supporting the notion that ATP binding may be a more important regulator of FtsA activity on the Z ring than ATP hydrolysis (Beuria et al., 2009; Loose and Mitchison, 2014; Osawa and Erickson, 2013; Szwedziak et al., 2012). However, it is also possible that other factors in vivo can stimulate FtsA ATPase activity above the levels we can detect in vitro, or that the conditions of our assay can be further optimized. We attempted to identify the former by adding additional purified divisome proteins or protein domains to our ATPase activity assay, but so far we have not identified any factor or combination of factors that stimulate further ATP hydrolysis by FtsA (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this work, we characterized the ftsA27 thermosensitive mutant, which has been previously used to inactivate FtsA in genetic experiments. Like all other known thermosensitive alleles of ftsA, ftsA27 has a point mutation in or near the ATP binding site, and we confirmed that the FtsA27 protein is defective at binding and hydrolyzing ATP in vitro. In vivo conditions for ATP binding may be more favorable, allowing FtsA27 to be at least partially functional at 30°C. Our in vivo results suggest that FtsA27 is also defective at binding to FtsZ at the permissive temperature, but the defect is likely exacerbated at higher temperatures, leading to delocalization of FtsA27 from the Z ring. Together, our genetic and biochemical data are consistent with the idea that ATP enhances the ability of FtsA to bind FtsZ (Beuria et al., 2009; Loose and Mitchison, 2014).

The genetic characteristics of the ftsA27 suppressor mutants are summarized in Figure S7. They fall roughly into two different classes: (1) mutants that likely affect ATP binding directly and (2) mutants that likely affect protein-protein interaction directly. The G213A and P251L lesions, which correspond to Y215 and F253 in T. maritima, are the closest to the ATP binding site and fall into the first category. F253 is near, although not part of the active site. Y215, on the other hand, is in the active site and is predicted to make contacts with the alpha, beta, and gamma phosphates of ATP (van den Ent and Löwe, 2000). According to our genetic and cytological assays, the G213A and P251L mutant proteins of E. coli restore interactions between FtsA27 and the Z ring, probably FtsZ itself, to WT levels, but do not further enhance these interactions. These results add in vivo support to the idea that ATP binding by FtsA is required for its interaction with the Z ring. However, our results with G213A suggest that increased ATP binding above WT levels does not correlate with significantly increased binding to the Z ring above WT levels.

The G50E and T249M lesions at the FtsA-FtsA interface (Szwedziak et al., 2012) fall into the second category and may affect FtsA-FtsA interactions directly. Both have increased affinity for the Z ring compared to WT FtsA by our genetic assays, and bypass the requirement for zipA more efficiently than any of the other ftsA27 suppressor mutants. Recently, a strong correlation was made between ability to bypass ZipA and decreased oligomerization of FtsA, although these in vivo assays were indirect and relied on fusions or MTS deletions of FtsA (Pichoff et al., 2012). This model contradicts our previous model in which we made the case, based on different in vivo assays (bacterial two-hybrid analysis and behavior of tandem FtsA fusions), that mutants that oligomerized better than WT FtsA, such as FtsA*, had a gain of function such as bypass of ZipA, whereas lower FtsA oligomerization resulted in loss of function (Shiomi et al., 2007b). The fact that many of the lesions identified by Pichoff et al. localize to the FtsA subunit interface lends credence to their model. Our bacterial two-hybrid results may have been confounded by stronger FtsA-FtsZ interactions, which may have caused false positive FtsA-FtsA interactions; likewise, our tandem fusions, which we thought would mimic dimerization (Shiomi et al., 2007b), may have paradoxically interfered with proper FtsA dimerization by forcing a sterically unfavorable interaction. However, without a definitive biochemical assay for FtsA oligomerization, it is difficult to directly confirm either model. Using our purified proteins active for ATP hydrolysis, we have attempted to measure oligomerization differences between FtsA variants using native gels or equilibrium density gradients, but have not yet had success (Herricks, et al., unpublished data). It should be emphasized that apart from the FtsA in vivo polymer assay (see below), other in vivo assays such as yeast two-hybrid analysis show only small qualitative effects on FtsA-FtsA interactions for many of the ZipA bypass mutants (Pichoff et al., 2012).

Despite exhibiting some phenotypes associated with increased interaction with the Z ring according to our assays, the H159L, P250T and Y139D proteins all have intermediate phenotypes, with H159L and Y139D being more similar to the lesions in category 1, and P250T being more similar to the lesions in category 2. Overall, our results suggest that gain-of-function alterations in the ATP binding site have a considerable effect on ATP binding and hydrolysis, but less effect on FtsA interactions with the Z ring (and thus probably FtsZ itself). Conversely, mutations closer to the FtsA-FtsA interface had significant impacts on both ATP binding and FtsA interactions with the Z ring. Work by others suggests that changes in some of the residues we analyzed or in adjacent residues also significantly affect FtsA-FtsA interactions (Hsin et al., 2013; Pichoff et al., 2012), as would be predicted by their location. Consistent with this model, we showed here that MTS-deleted versions of the original FtsA27 lesion S195P as well as its ATP site suppressor G213A readily formed large polymers in vivo, whereas MTS-deleted versions of G50E and Y139D did not. This is consistent with G50E and Y139D suppression of S195P by disrupting FtsA-FtsA interactions, whereas G213A suppresses via a distinct mechanism. We speculate that FtsA self-interaction strongly influences, and may compete with, its ability to bind ATP and interact with the Z ring. Clearly, future work on the in interplay with these factors in vitro will be needed to confirm this idea.

The fact that FtsA27 can divide cells quite normally at permissive temperatures despite its severe defect in ATP transactions and probable weaker interaction with FtsZ supports the idea that other divisome factors such as ZipA have overlapping functions. ZipA, apart from its membrane tethering properties, likely functions mainly to keep FtsZ bundled and polymerized in order to promote FtsA-FtsZ binding during early stages of Z ring formation. We suggest that variants of FtsA that can bypass ZipA do so by increasing the ability of FtsA to bind to the Z ring, with decreasing oligomerization as one potential pathway towards this end. For the most well characterized of the ZipA bypass suppressors, R286W, this comes at the cost of circumventing a cell size checkpoint, as R286W cells divide at too small a size (Geissler et al., 2007). This is consistent with a role for ZipA in managing the earliest stages of proto-ring assembly, possibly suppressing FtsZ treadmilling until the ring is more mature (Loose and Mitchison, 2014).

As zipA is only conserved in the gamma-proteobacteria, our model suggests that in other classes of bacteria that contain FtsA, (i) FtsA-FtsZ interactions may be stronger and do not require a ZipA-like protein to promote their interaction; (ii) FtsZ may polymerize and/or bundle more efficiently in vivo, allowing FtsA to interact more efficiently; or (iii) other bundling proteins perform the function of ZipA and promote FtsZ polymerization and FtsA-FtsZ interactions.

Finally, we have shown for the first time that E. coli FtsA does indeed hydrolyze ATP, with the ATPase activity of various mutant proteins correlating with ATP binding activity. What is the role of FtsA ATP hydrolysis? By using a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, Loose & Mitchison (2014) showed that ATP hydrolysis by FtsA was not essential for dynamic FtsA-FtsZ interactions in vitro. However, ATP hydrolysis by FtsA may provide energy for the constriction of the divisome, or it may induce conformational changes that allow FtsA to recruit downstream divisome proteins in its ADP-bound form. Interestingly, FtsA* displays increased ATP binding and hydrolysis in vitro as well as increased subunit turnover at the Z ring (Geissler et al., 2007), which suggests that the increase in turnover correlates with increased ATP binding and/or hydrolysis. Mutants with hydrolysis defects but not ATP binding defects may be able to uncouple the roles of ATP binding and hydrolysis. This work will continue to drive our understanding of bacterial cytokinesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and growth media

Except for where indicated, E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 30°C, 37°C or 42°C as indicated and supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich), ampicillin (50 µg ml−1; Fisher Scientific), kanamycin (25 µg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich), chloramphenicol (10 µg ml−1; Acros Organics) and glucose (1%; Sigma-Aldrich), as needed. Cells were induced with 0.01 – 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) or 1–10 µM sodium salicylate one hour prior to microscopic analysis or overnight on LB agar plates as indicated. Cloning was performed using E. coli strain XL1 Blue. E. coli strain C43 (BL21-DE3 derivative) was used for gene expression from pET28a.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. WM4107 was constructed by transducing a P1 phage lysate grown on WM2965 (MCA27) into WM1074 and selecting for the tetracycline resistance linked to the leu locus. Resistant colonies were then screened for temperature sensitivity, which was observed at the expected cotransduction rate of 50%. The presence of the ftsA27 allele was confirmed by sequencing ftsA genes PCR-amplified from the genome. Using a similar method, we transduced the ftsA null allele from WM1281, which is 50% linked to leu+, into WM4107 derivatives containing various plasmids expressing ftsA alleles, selecting for Leu+ on M9 glucose medium, screening for tetracycline sensitivity, and confirming the presence of the null allele (a frameshift at the unique BglII site within ftsA) by sequencing.

Table 3. Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| XL1-Blue | recA1 cloning strain | Stratagene |

| C43(DE3) | F – ompT hsdSB (rB- mB-) gal dcm (DE3) | Miroux and Walker, 1996 |

| WM1074 | MG1655 ΔlacU169 | Laboratory collection |

| WM1115 | WM1074 ftsA12(ts) | Laboratory collection |

| WM1281 | PB103 ftsA0 recA::Tn10 | Hale and de Boer, 1997 |

| WM1659 | WM1074 ftsA(R286W) | Geissler et al., 2003 |

| WM2965 | MCA27 [MC4100r, leu-260::Tn10, ftsA27(ts)] | E. coli Genetic Stock Center |

| WM2991 | W3110 zipA1(ts) | Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2002 |

| WM4107 | WM1074 leu-260::Tn10, ftsA27(ts) | This study |

| WM4585 | WM4107 ftsA(G213A, S195P) | This study |

| WM4586 | WM4107 ftsA(G50E, S195P) | This study |

| WM4587 | WM4107 ftsA(H159L, S195P) | This study |

| WM4588 | WM4107 ftsA(T249M, S195P) | This study |

| WM4589 | WM4107 ftsA(P250T, S195P) | This study |

| WM4590 | WM4107 ftsA(P251L, S195P) | This study |

| WM4591 | WM4107 ftsA(Y139D, S195P) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDSW208 | Derivative of pBR322 with weaker Ptrc promoter | Weiss et al., 1999 |

| pDSW210 | Derivative of pBR322 with weakest Ptrc promoter | Weiss et al., 1999 |

| pKG110 | pACYC184 derivative with PnahG promoter | J. S. Parkinson |

| pET28a | Expression vector with PT7 promoter | Novagen |

| pWM1260 | his6-ftsA in pET28a | Geissler et al., 2003 |

| pWM1609 | his6-ftsA(R286W) in pET28a | Geissler et al., 2003 |

| pWM4327 | his6-ftsA27 in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4522 | his6-ftsA(G50E, S195P) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4523 | his6-ftsA(G213A, S195P) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4760 | his6-ftsA(G50E) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4819 | his6-ftsA(G213A) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM2060 | pDSW210 without gfp | Geissler and Margolin, 2005 |

| pWM2784 | flag in pDSW210 | Shiomi and Margolin, 2007a |

| pWM2785 | flag-ftsA in pDSW210 | Shiomi and Margolin, 2007b |

| pWM2787 | flag-ftsA(R286W) in pDSW210 | Shiomi and Margolin, 2007b |

| pWM3073 | zipA in pKG110 | Shiomi and Margolin, 2007b |

| pWM3241 | flag-ftsAΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM3242 | flag-ftsA(R286W)ΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM4900 | flag-ftsA(G50E)ΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM4901 | flag-ftsA(Y139D)ΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM4902 | flag-ftsA(S195P)ΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM4903 | flag-ftsA(G213A)ΔMTS in pDSW208 | This study |

| pWM3928 | flag-ftsA27(ts) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4115 | flag-ftsA(G213A) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4116 | flag-ftsA(T249M) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4424 | flag-ftsA(G50E) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4425 | flag-ftsA(Y139D) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4426 | flag-ftsA(P250T) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4427 | flag-ftsA(P251L) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4428 | flag-ftsA(H159L) in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4653 | flag-ftsA in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4654 | flag-ftsA(R286W) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4655 | flag-ftsA(R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4656 | flag-ftsA(R286W, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4658 | flag-ftsA(G50E, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4659 | flag-ftsA(G213A, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4767 | flag-ftsA(Y139D, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4868 | flag-ftsA(H159L, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4869 | flag-ftsA(T249M, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4870 | flag-ftsA(P250T, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

| pWM4871 | flag-ftsA(P251L, R300E) in pWM2060 | This study |

Isolation of intragenic suppressors

Suppressors of ftsA27 were isolated by growing cultures of WM4107 (ftsA27) to early log phase at 30°C. Cultures were then shifted to 42°C for one hour. Serial dilutions of each culture were plated on LB agar at 30°C to determine viability, and on pre-warmed LB agar incubated overnight at 42°C to select for thermoresistant mutants. The ftsA alleles from colonies that survived at 42°C were PCR-amplified from the chromosome using primers 822 and 823 and cloned as XbaI-PstI fragments into pWM2784. The constructs were then transformed into WM1115 (ftsA12ts) and tested for complementation at 42°C. The ftsA genes from plasmid constructs that could complement were sequenced, and identified as either revertants or harboring intragenic suppressors of the original ftsA27 mutation.

DNA and protein manipulation and analysis

Standard protocols or manufacturers’ instructions were used to isolate and manipulate DNA, including preparation of plasmid DNA, restriction endonuclease digest, DNA ligation, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs, Inc. (NEB). Plasmid DNA was purified using Wizard Plus SV miniprep DNA purification systems and DNA fragments were purified with Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up systems from Promega. Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase from NEB and Kapa Biosystems High Fidelity Readymix from VWR International, LLC were used for PCR. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay from Thermo Scientific. DNA sequencing was performed by Genewiz, Inc. and SeqWright, Inc. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and are listed in Table S1. The final versions of all relevant clones were sequenced to verify correct construction. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package (Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311).

Plasmid construction

All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. For protein purification constructs, ftsA alleles were PCR amplified with primers 822 and 1514 and cloned as KpnI-EcoRI fragments into pWM1260 to replace the resident ftsA gene. Mutant flag-ftsA constructs in pDSW210 were made by PCR-amplifying the ftsA alleles with primers 822 and 823 and cloning the resulting products as XbaI-PstI fragments into pWM2784. For flag-ftsA constructs in pWM2060, we PCR-amplified ftsA alleles fused to flag using primers 888 and 823, and cloned the products as EcoRI-PstI fragments into pWM2060. Most ftsA alleles were PCR-amplified from chromosomal DNA using primers 822 and 823.

Point mutations were created by site-directed mutagenesis with combinatorial PCR using 822 and 823 as outside primers. For creation of ftsA27 suppressor alleles without S195P, we used site-directed mutagenesis with combinatorial PCR to mutate P195 back to S195 using inside primers 1953 and 1954.

To express FtsA ΔMTS derivatives at levels sufficient to make visible FtsA polymers in cells, we cloned FtsAΔMTS in pDSW208-FLAG, which has a stronger IPTG-inducible promoter than pDSW210. Using existing pDSW210 derivatives as templates, the mutant ftsAs were cloned as XbaI-PstI fragments using primers 822 and 998, which results in a construct expressing a FLAG-FtsA with its C-terminal 15 amino acid residues removed.

Protein purification

His6-FtsA and its derivatives were expressed from pET28a in E. coli strain C43(DE3). Cells were grown to an optical density (OD600) of 0.4 to 0.6 and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 hours at 30°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed in buffer A (20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 25 mM potassium glutamate, and 5 mM MgCl2). Cell pellets were stored at -80°C. Prior to lysis, cell pellets were thawed and resuspended in lysis buffer (buffer A, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma-Aldrich), cOmplete, EDTA-free cocktail protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Science), and 5 mM imidazole). After homogenization, cells were lysed by 4 passages through a French pressure cell (SLM Aminco). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 23,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Clarified lysates were incubated with equilibrated TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Clonetech Laboratories, Inc.) for 2 hours at 4°C. Lysate-resin mixtures were then poured into gravity-flow columns and the lysates were allowed to flow through. The resin was washed with 200 ml each of buffer A containing 5 mM, 20 mM and 30 mM imidazole. His-tagged proteins were eluted from the resin with buffer A containing 150 mM imidazole. Eluate fractions containing protein were dialyzed two times at 4°C for a total of at least 16 hours in buffer A with 1 mM DTT and 20% glycerol (FtsA buffer). Purified proteins were then distributed into 100 µL aliquots and stored at -20°C. Purity was determined by Coomassie staining after SDS-PAGE (Fig. S6).

Protein Analysis

Crude extracts, eluates, and purified proteins were resuspended in 5X SDS loading buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 25% glycerol, 0.5 M DTT, 10% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue), boiled for 10 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE in a Mini PROTEAN Tetra Cell (Bio-Rad) using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were stained with Coomassie protein stain for at least one hour followed by incubation in destaining solution.

For Western Blot analysis proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a Bio-Rad Mini Trans-Blot Cell. Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG primary antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Polyclonal anti-ZipA serum was affinity purified according to Levin, 2002. Primary antibody dilutions of 1:5,000 or 1:10,000 were used. Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Sigma-Aldrich) were used at a 1:10,000 or 1:5000 dilutions. Western Lightning ECL Pro kit (PerkinElmer) was used to detect chemiluminescence.

ATP binding

To measure ATP binding by FtsA and FtsA mutants, 50 nM BodipyFL-ATP (Life Technologies) was incubated with 0.25 µM of the indicated purified protein in FtsA buffer at 30°C for 15 minutes. Samples were passed through a nitrocellulose membrane using a slot-blot apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instruments). The membrane was presoaked in FtsA buffer for at least 2 hours at 4°C. The membrane was washed with 1 mL of FtsA buffer after samples passed through. Fluorescence retained on the membrane was imaged with a ChemiDoc MP System (BioRad) and staining intensities within an area of constant size for each sample were quantified using Image J software.

ATP hydrolysis

The EnzChek Phosphate Assay Kit from Life Technologies is very sensitive and was therefore used to detect phosphate release from the low concentrations of FtsA and its derivatives. The manufacturer’s instructions were modified for 96-well format. Briefly, FtsA or its derivative was diluted to 0.1–1 µM in FtsA buffer. Assay reagents, 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine riboside (MESG) substrate and purine nucleoside phosphorylase, were added to 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 with or without ATP (Sigma-Aldrich). The protein was mixed with the assay reagents in a clear, flat-bottom 96-well plate. OD360 was read using a Synergy MX Microplate Reader (BioTek) every 10–15 minutes for 1–4 hours at 37°C unless otherwise indicated. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate and analyze the data. We initially detected a very low rate of phosphate release with WT FtsA (0.5 mol pi/mol FtsA/minute) using the EnzChek assay. We then tested different buffers and protein concentrations to see if we could optimize conditions for FtsA ATP hydrolysis. Our optimal buffer composition was 87 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 3.7 mM MgCl2, 74 mM KCl, 18.5 mM potassium glutamate, 0.74 mM DTT, 0.74 mM EDTA, and 14.8% glycerol. Figures and figure legends indicate differences in buffer composition for given experiments.

Microscopy

For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were grown to mid-log phase at the indicated temperatures and fixed using paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde as previously described (Levin, 2002). Briefly, 500 µL of mid-log phase cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature followed immediately by incubation for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were washed 3 times with 1X PBS and resuspended in 1X GTE. FtsA was stained using 1:500 anti-FtsA primary antibody and 1:200 secondary anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies) or DyLight 550 (Pierce). Anti-FtsZ was stained with 1:2000 anti-FtsZ primary antibody and 1:200 of the Alexa Fluor 488 or DyLight 550 conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. Fluorescence images were captured using an Olympus BX60 microscope with a 100X oil immersion objective and a Hamamatsu C8484 digital camera with HCImage software. Images were compiled using Adobe Photoshop.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank past and present members of the Margolin lab for helpful discussions. We are indebted to Kevin A. Morano, Ph.D., for the use of the plate reader and technical assistance, and Nicholas De Lay, Ph.D., for the use of the ChemiDoc System. This work was supported by NIH grant R01-GM61074 to W.M. a Ruth Kirschstein NRSA (F31-GM099422) to J.R.H., and the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- Addinall SG, Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring formation in fts mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3877-3884.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuria TK, Mullapudi S, Mileykovskaya E, Sadasivam M, Dowhan W, Margolin W. Adenine nucleotide-dependent regulation of assembly of bacterial tubulin-like FtsZ by a hypermorph of bacterial actin-like FtsA. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14079–14086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808872200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. An ATPase domain common to prokaryotic cell cycle proteins, sugar kinases, actin, and hsp70 heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7290–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busiek KK, Eraso JM, Wang Y, Margolin W. The early divisome protein FtsA interacts directly through its 1c subdomain with the cytoplasmic domain of the late divisome protein FtsN. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1989–2000. doi: 10.1128/JB.06683-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busiek KK, Margolin W. A role for FtsA in SPOR-independent localization of the essential Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsN. Mol Microbiol. 2014;92:1212–1226. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabré EJ, Sanchez-Gorostiaga A, Carrara P, Ropero N, Casanova M, Palacios P, Stano P, Jimenez M, Rivas G, Vicente M. Bacterial division proteins FtsZ and ZipA induce vesicle shrinkage and cell membrane invagination. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:26625–26634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin BD, Geissler B, Sadasivam M, Margolin W. Z-ring-independent interaction between a subdomain of FtsA and late septation proteins as revealed by a polar recruitment assay. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7736–7744. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7736-7744.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Din N, Quardokus EM, Sackett MJ, Brun YV. Dominant C-terminal deletions of FtsZ that affect its ability to localize in Caulobacter and its interaction with FtsA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1051–1063. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feucht A, Lucet I, Yudkin MD, Errington J. Cytological and biochemical characterization of the FtsA cell division protein of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:115–125. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayda RC, Henk MC, Leong D. C-shaped cells caused by an ftsA mutation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5362–5370. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5362-5370.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler B, Elraheb D, Margolin W. A gain-of-function mutation in ftsA bypasses the requirement for the essential cell division gene zipA in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4197–4202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0635003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler B, Margolin W. Evidence for functional overlap among multiple bacterial cell division proteins: compensating for the loss of FtsK. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:596–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler B, Shiomi D, Margolin W. The ftsA* gain-of-function allele of Escherichia coli and its effects on the stability and dynamics of the Z ring. Microbiology. 2007;153:814–825. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001834-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, de Boer PA. Direct binding of FtsZ to ZipA, an essential component of the septal ring structure that mediates cell division in E. coli. Cell. 1997;88:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, De Boer PA. Recruitment of ZipA to the septal ring of Escherichia coli is dependent on FtsZ and independent of FtsA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:167–176. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.167-176.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, Rhee AC, de Boer PA. ZipA-induced bundling of FtsZ polymers mediated by an interaction between C-terminal domains. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5153–5166. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5153-5166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, de Boer PAJ. ZipA Is required for recruitment of FtsK, FtsQ, FtsL, and FtsN to the septal ring in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2552–2556. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.9.2552-2556.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rocamora VM, García-Montañés C, Rivas G, Llorca O. Reconstitution of the Escherichia coli cell division ZipA–FtsZ complexes in nanodiscs as revealed by electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsin J, Fu R, Huang KC. Dimer dynamics and filament organization of the bacterial cell division protein FtsA. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4415–4426. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhatla A, Bhattacharya A, Panda D. ZipA binds to FtsZ with high affinity and enhances the stability of FtsZ protofilaments. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin PA. Methods in Microbiology. London: Academic Press Ltd; 2002. Light microscopy techniques for bacterial cell biology; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. Recruitment of ZipA to the division site by interaction with FtsZ. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1853–1861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loose M, Mitchison TJ. The bacterial cell division proteins FtsA and FtsZ self-organize into dynamic cytoskeletal patterns. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:38–46. doi: 10.1038/ncb2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Margolin W. Genetic and functional analyses of the conserved C-terminal core domain of Escherichia coli FtsZ. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7531–7544. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7531-7544.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin W. Themes and variations in prokaryotic cell division. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:531–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos A, Monterroso B, Zorrilla S, Reija B, Alfonso C, Mingorance J, Rivas G, Jiménez M. Isolation, characterization and lipid-binding properties of the recalcitrant FtsA division protein from Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira IS, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. Detailed microscopic study of the full ZipA:FtsZ interface. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinformat. 2006;63:811–821. doi: 10.1002/prot.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosyak L, Zhang Y, Glasfeld E, Haney S, Stahl M, Seehra J, Somers WS. The bacterial cell-division protein ZipA and its interaction with an FtsZ fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography. EMBO J. 2000;19:3179–3191. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Erickson HP. Liposome division by a simple bacterial division machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11000–11004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222254110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis-Bleau C, Sanschagrin F, Levesque RC. Peptide inhibitors of the essential cell division protein FtsA. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2005;18:85–91. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazos M, Natale P, Vicente M. A specific role for the ZipA protein in cell division: stabilization of the FtsZ protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3219–3226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. Unique and overlapping roles for ZipA and FtsA in septal ring assembly in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2002;21:685–693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. Identification of a region of FtsA required for interaction with FtsZ. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1129–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichoff S, Shen B, Sullivan B, Lutkenhaus J. FtsA mutants impaired for self-interaction bypass ZipA suggesting a model in which FtsA’s self-interaction competes with its ability to recruit downstream division proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:151–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potluri L-P, Kannan S, Young KD. ZipA Is required for FtsZ-dependent preseptal peptidoglycan synthesis prior to invagination during cell division. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5334–5342. doi: 10.1128/JB.00859-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RayChaudhuri D. ZipA is a MAP–Tau homolog and is essential for structural integrity of the cytokinetic FtsZ ring during bacterial cell division. EMBO J. 1999;18:2372–2383. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rico AI, García-Ovalle M, Mingorance J, Vicente M. Role of two essential domains of Escherichia coli FtsA in localization and progression of the division ring. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1359–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AC, Begg KJ, Donachie WD. Mapping and characterization of mutants of the Escherichia coli cell division gene, ftsA. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AC, Begg KJ, MacArthur E. Isolation and characterization of intragenic suppressors of an Escherichia coli ftsA mutation. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:623–631. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90075-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Dopazo A, Pla J, Robinson AC, Vicente M. Characterization of mutant alleles of the cell division protein FtsA, a regulator and structural component of the Escherichia coli septator. Biochimie. 1994;76:1071–1074. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Lutkenhaus J. The conserved C-terminal tail of FtsZ is required for the septal localization and division inhibitory activity of MinCC/MinD. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:410–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi D, Margolin W. The C-terminal domain of MinC inhibits assembly of the Z ring in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007a;189:236–243. doi: 10.1128/JB.00666-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi D, Margolin W. Dimerization or oligomerization of the actin-like FtsA protein enhances the integrity of the cytokinetic Z ring. Mol Microbiol. 2007b;66:1396–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwedziak P, Wang Q, Freund S, Löwe J. FtsA forms actin-like protofilaments. EMBO J. 2012;31:2249–2260. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ent F, Löwe J. Crystal structure of the cell division protein FtsA from Thermotoga maritima. EMBO J. 2000;19:5300–5307. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Chen JC, Ghigo JM, Boyd D, Beckwith J. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:508–520. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.508-520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.