Abstract

The effect of calcium channel blockers (CCBs), beta blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on the prognosis of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is largely unknown. We collected data on the use of these medications on 1043 patients with AML excluding promyelocytic leukemia diagnosed and treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 2000 and 2012. Treatment with either amlodipine or diltiazem predicted a worse overall survival (HR 1.6 95% CI 1.22-2.06, p<0.0001). There was no difference in survival depending on whether the patients were taking beta blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs. The effect of CCBs on survival was independent from the NCCN risk classification, age, performance status, response to treatment, year of diagnosis and CD34 levels, assessed by flow cytometry (HR=1.39, 95% CI 1.05-1.80, p=0.02). Treatment with either amlodipine or diltiazem predicts worse survival in patients with AML independent of known prognostic factors.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, amlodipine, diltiazem, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) involves the predominantly clonal expansion of myeloid cells, driven by a now well-characterized mutation panel that share the culprit elements of bone marrow myeloid cell increase with concomitant maturation arrest[1]. The outcome largely depends on the specific genetic alterations: different cytogenetic patterns stratify the patients for distinct prognostic groups[2], which in recent years were refined by a plethora of prognostic factors that include mutations, SNPs, proteins and microRNAs, incorporated in the prognostication schemes[3]. Although AML can be diagnosed at any age, the incidence peaks in the 7th decade of life[4], at a time when a considerable number of patients are likely to be treated for other comorbid conditions.

The impact of beta blockers, angiocoverting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs) on the survival of patients with AML is largely unknown. Nevertheless, an association between the chronic use of antihypertensive drugs and cancer has been sporadically suggested: patients on immediate release CCBs have been reported to carry a higher risk for breast cancer in a recent study[5] and in another report ACE inhibitors and CCBs render a hazard for developing lung cancer[6]. These results remain controversial as they have not been validated in separate cohorts. With regards to cancer prognosis, patients with different types of cancer who use ACE inhibitors have lower rates of mortality while they have longer time to progression when compared with patients who are not on ACE inhibitors[7]. Likewise, patients with breast cancer[8] and melanoma[9] who receive beta blockers have extended survival.

Certain biochemical evidence suggests that commonly prescribed antihypertensives can exert biological effect on AML cells. Angiotensin II receptors have been shown to be present in hematopoietic progenitor cells[10], and components of the renin angiotensin system (RAS) are expressed in the bone marrow microenvironment of AML cells and are postulated to exert a regulatory function by participating in autocrine and paracrine loops[11]. Interestingly, treatment of certain AML cell lines with ACE inhibitors or ARBs results in inhibition of cell growth and promotion of apoptosis associated with decreased c-myc expression[12]. With regards to beta blockers, the non-selective beta blocker carvedilol is a very potent inhibitor of the myeloid leukemia K562 cells[13], whereas propranolol exerts a cytotoxic effect on the monocyte cell line U937[14].

Calcium homeostasis participates in major cellular processes in cancer[20]. Preclinical data propose potential effect of calcium with the regulation of biological processes in AML, although the exact pathophysiology is not well-understood. First, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) induces apoptosis in AML cell lines by increasing the intracellular calcium concentration[21]. Traditionally, 4-AP is used to block high voltage dependent potassium channels[22] but it has been also shown to induce N-type calcium channels by directly acting on the voltage-activated calcium channel beta subunit[23]. Second, Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 a chief component of the calcium entry mechanism in non-excitable cells is present in AML cell lines and is involved in the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells[24]. Third, the farnesyl-transferase inhibitor, tipirfanib induces apoptosis in AML cells by inducing calcium influx that seems to be mediated by a store operating calcium entry (SOCE)-like pathway[25]. SOCE is found to play a role in calcium homeostasis of non-excitable cells[17] and to interact with CCBs in some reports[18, 19].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the potential effect of CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs and beta blockers on the prognosis in a large retrospective cohort of patients with AML treated at a single center.

Methods

Ethics declaration

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center which waived the need for written informed consent by the patients whose records were retrospectively reviewed. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as well as the institutional ethical requirements.

Data collection

We identified the patients diagnosed with AML from December 1999 to January 2013 who received treatment at MD Anderson Cancer Center. We used the electronic code for AML to search the MD Anderson database. We excluded patients who were diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia. We then collected the following data from electronic charts: date of diagnosis, treatment start, progression and last follow up, best response, cytogenetics, mutational analysis, age, sex, race, CD34 flow cytometry, performance status (PS), FAB classification and contemporary treatment with beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Patients were classified into either low CD34 or high CD34 on the basis of the median CD34 count. Patients were considered to have good PS if PS was ≤ 1 and unfavorable PS otherwise. In addition, we recorded treatment related deaths as well as whether the patients were alive or dead at the time of last follow up. Response to treatment was assessed with the NCCN definition of complete response and treatment failure[26]. Briefly, patients were classified as complete responders if they achieved a morphologic leukemia free state and were transfusion independent. Additionally, If cytogenetics and molecular abnormalities were identified initially, then normalization of the cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities were required for complete response. Patients who did not achieve a complete response were classified as poor responders. Finally, we included patients who died during treatment in a separate category.

We confirmed that most patients received cytarabine (AraC) based induction chemotherapy. The data concerning the beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs were obtained from the medication reconciliation section of the patient electronic charts and cross validated with review of the electronic prescriptions from the MD Anderson Cancer Center pharmacy.

Statistics

We applied the chi square statistic to calculate odds ratios from contingency tables and identify any imbalances across the patient antihypertensive subgroups with regards to specific clinicopathologic data. We used the Kaplan Meier method to construct survival curves. Statistical significance was evaluated with the logrank p value. Results were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05. The univariate Cox model was used to calculate the hazard ratios and the proportional hazards model was used to assess independent effects of the variables that were found to be significantly affecting overall survival in univariate analysis. All statistical analysis was performed with JMP version 10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

We identified 1043 patients with AML as summarized in table 1. There were no patients with promyelocytic leukemia. The cohort consisted of 585 men and 458 women, 487 were younger than 60 years of age and 556 were older than 60 years. The majority (856) had a performance status of 0 or 1. After applying the NCCN prognostic criteria that combine cytogenetics with mutation information, we classified 135 patients as having favorable risk, 507 intermediate and 346 as poor risk. Patients were followed for a median of 13.5 months (range 1.13-132.4). Older patients were more likely to receive treatment with at least one of the antihypertensive agents; however there were no other differences between the patients on different classes of antihypertensives with regards to the patients' demographics.

Table 1. Population descriptive statistics.

| Variable | All patients | CCBs | BBs | ACEi/ARBs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Yes | No | p | Yes | No | p | Yes | No | p | |||

| n | 1043 | 83 | 960 | 160 | 883 | 88 | 955 | ||||

| Age | •≤60 | 487 | 32 | 455 | 0.12 | 60 | 427 | 0.01 | 27 | 460 | 0.0017 |

| •>60 | 556 | 51 | 505 | 100 | 456 | 61 | 495 | ||||

| PS | •≤1 | 856 | 66 | 790 | 0.42 | 127 | 729 | 0.5 | 72 | 784 | 0.9 |

| •>1 | 168 | 16 | 152 | 28 | 140 | 14 | 154 | ||||

| NCCN prognosis strata | •Good | 135 | 5 | 130 | 0.06 | 26 | 109 | 0.3 | 14 | 121 | 0.5 |

| •Intermediate | 507 | 39 | 468 | 67 | 440 | 36 | 471 | ||||

| •poor | 346 | 35 | 311 | 55 | 291 | 31 | 315 | ||||

| Sex | •Male | 585 | 49 | 536 | 0.57 | 86 | 499 | 0.51 | 54 | 531 | 0.29 |

| •Female | 458 | 34 | 424 | 74 | 384 | 34 | 424 | ||||

| Follow up (months) | 13.5 (1.13-132.4) | 8.1 (1.16-63.7) | 14.1 (1.13-132.4) | 12.5 (1.16-113.8) | 13.8 (1.13-132.4 | 12.4 (1.33-94.4) | 13.6 (1.13-132.4 | ||||

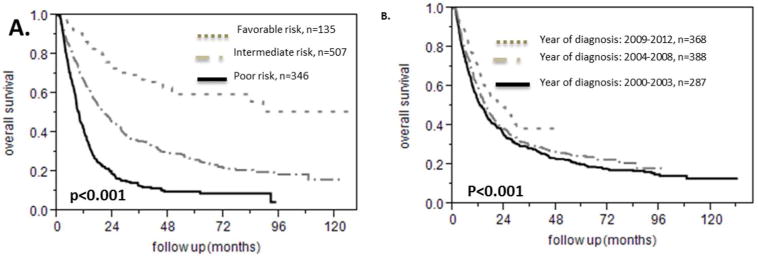

The NCCN prognosis stratification that assigns patients to one of three groups, favorable, intermediate or poor risk takes into account the cytogenetics in combination with the presence or absence of certain mutations that carry prognostic information[26]. We validated the NCCN prognostication strata in our cohort as shown in figure 1A: patients with favorable risk had the best prognosis, patients with intermediate risk had worse overall survival compared to patients with favorable risk and finally patients with poor risk had the worse prognosis (median survival for the favorable risk group risk not reached, for the intermediate group risk it was 20.4 months and for the poor risk group it was 9.4 months). The univariate Cox model hazard ratio of dying was 2.7 (95% CI 2.0-3.7) for the intermediate risk group in comparison to the favorable risk group, 2.0 (95% CI 1.7-2.35) for the poor risk group over the intermediate risk group and 5.4 (95% CI 4.0-7.6) for the poor risk group over the favorable risk group. Among the patients with intermediate cytogenetics, further prognostic classification based on presence or absence of CEBPA, NPM1, FLT3-ITD and c-KIT mutations, was able to identify three strata with distinct prognosis (supplementary figure 1). In addition, we observed that patients had a better survival the later they were diagnosed: median survival was 13.2 months (95% CI 10.9-15.73) for the patients who were diagnosed between 2000 and 2003, 15.33 months (95% CI 13-17.08) for the patients who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2007 and 23.43 months (95% CI 17.23-27.7) for the patients who were diagnosed from 2008 to 2012. The difference between the groups was statistically significant (p=0.0004, figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Survival analysis for different NCCN risk strata and year of diagnosis for patients with AML. A. NCCN prognosis classification correctly stratifies patients with AML in good, intermediate and poor risk. B. The prognosis of patients becomes better from 2000 to 2012.

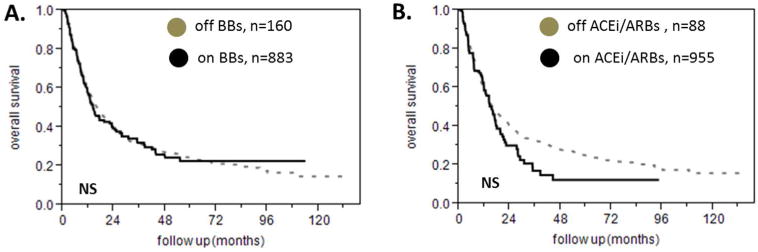

There were a total of 160 patients on beta blockers, 39 of whom were taking atenolol and 121 were taking metoprolol. There was no difference in the overall survival between patients who were on beta blockers versus the patients who were not on this class of medications as shown in figure 2A (univariate Cox model HR for the group on the beta blocker versus the group not on beta blocker 1.01 95% CI 0.82-1.24). We identified 35 patients who were taking valsartan, 55 patients who were taking lisinopril and 88 total on either ACE inhibitors or ARBs whereas 955 patients were taking none of those drugs. There were two patients who were reported to be taking both drugs. Being on an ACE inhibitor or ARB did not affect overall survival in this patient population as shown in figure 2B (hazard ratio for being on this class of medications over the rest of the patients 1.23 95% CI 0.94 to 1.58). Being on a beta blocker, an ACE inhibitor or ARB did not predict prognosis when we performed the subgroup analysis on the basis of age, sex, race, PS, NCCN prognostic group, type of response or CD34 count (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effect of beta blockers and ACE inhibitors and ARBs on survival of patients with AML. A. Treatment with a beta blocker does not affect survival in AML. B. Treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB does not affect prognosis in patients with AML.

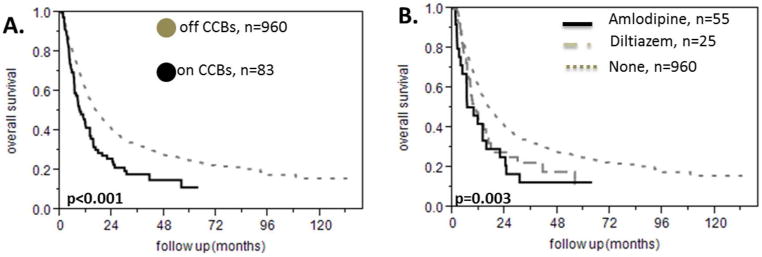

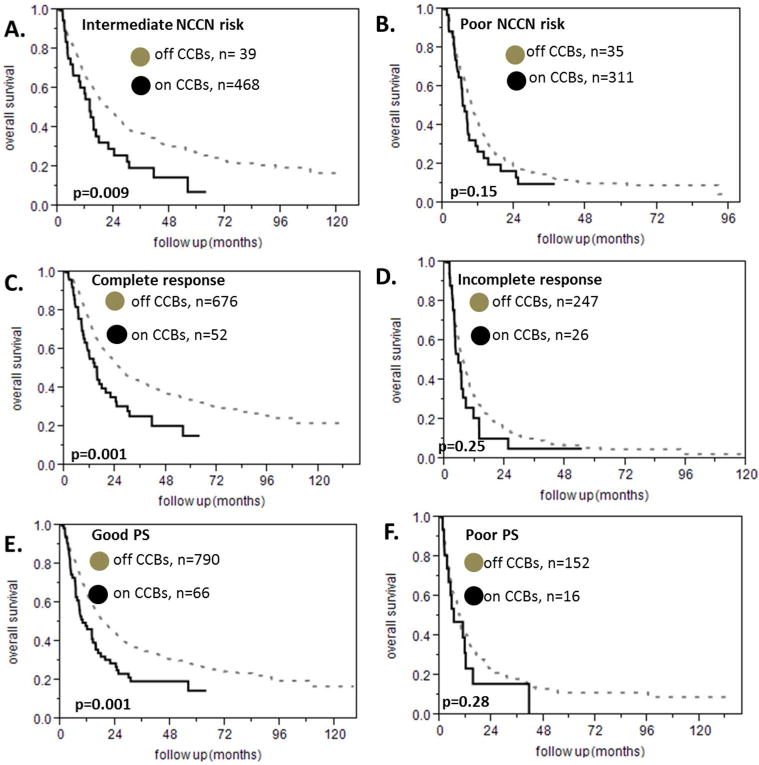

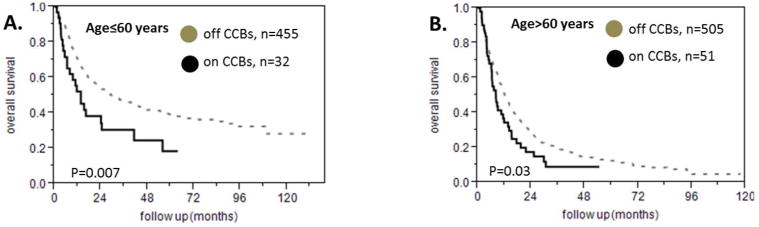

We found 83 patients who were taking calcium channel blockers. In particular, 58 were taking amlodipine and 28 were taking diltiazem while 3 were taking both of these medications. The remaining 960 patients did not take any CCBs. The median survival of patients on a CCB was 9 months versus 16.7 months for the patients who were not taking a CCB (HR 1.6 95% CI 1.22-2.06, p<0.0001 figure 3A) and there was no difference in the overall survival between the patients that received amlodipine and those who were treated with diltiazem (figure 3B). In the subgroup analysis we found that patients on a CCB had a shorter survival among the patients with intermediate NCCN prognostic risk (median survival 13.6 months versus 21.5 months, HR 1.6 95% CI 1.1-2.38, p=0.009, figure 4A) but not among the patients with poor NCCN prognostic risk (median survival 7.2 months versus 9.5 months, HR 1.31 95% CI 0.88-1.89, p=1.15, figure 4B). There were very few patients taking CCBs among the patients with favorable NCCN prognostic risk for the survival analysis to be meaningful. In addition, being on either amlodipine or diltiazem predicted a shorter survival among the patients who achieved a complete response to treatment (median survival 15.1 versus 26.5 months, p=0.001, HR 1.75 95% CI 1.22-2.42, figure 4C) but this was not true for the patients who had a poor response to treatment (median survival 5.3 versus 7.3 months, p= 0.25, HR 1.3 95% CI 0.8-1.98, figure 4D). The prognostic impact of CCB was present in the group of patients with good PS (median survival 9.5 months for the patients on CCBs versus 19.3 months for the patients who were not taking CCBs, p=0.0011, HR 1.62 95% CI 1.19-2.15 figure 4E) but not in the subgroup of patients with poor PS (median survival 6.4 months for the patients on CCBs versus 9.2 months for the patients who were not taking CCBs, p=0.28, HR 1.36 95% CI 0.73-2.33 figure 4F). We divided the patients into young and old using 60 years of age as a cut off. The usage of amlodipine or diltiazem was associated with worse survival in both subgroups (for patients age ≤ 60 years HR 1.78 95% CI 1.13-2.67, p=0.007 as shown in figure 5A, for patients age > 60 years, HR 1.42 95% CI 1.01-1.95, p=0.03 as shown in figure 5B). Finally, taking a CCB did not predict different response to treatment (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of the calcium channel blockers diltiazem and amlodipine on survival of patients with AML. A. Patients with AML who have been treated with the calcium channel blockers diltiazem or amlodipine have worse prognosis compared to the patients who are not receiving either of these drugs. B. The effect of calcium channel blockers on survival is the same for diltiazem and amlodipine.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses for the effect of calcium channel blockers on survival of patients with AML for different NCCN risk strata, different response to treatment and different performance status. A. The negative effect of calcium channel blockers on survival in AML is present in patients with intermediate NCCN risk. B. This is not true for patients with poor NCCN risk. There were not enough patients on calcium channel blockers and good NCCN risk to perform a survival analysis In that subgroup C. Patients with AML and complete response to treatment have worse prognosis when they receive a calcium channel blocker. D This is not true for patients who had a poor response to treatment. Patients who died during treatment were excluded from this analysis E. Patients with AML and good performance status have worse prognosis when they receive a calcium channel blocker. F. This is not true in the case of patients with poor performance status.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analyses for the effect of calcium channel blockers on survival of patients with AML of different age. A. Patients on calcium channel blockers who are younger than 60 years of age have shorter survival compared to patients who are not on calcium channel blockers. B. The same is true for patients who are older than 60 years of age.

We developed a proportional hazards model to assess whether the effect of CCBs on overall survival was independent of the variables that were found to be significantly affecting survival in the univariate analysis. Table2 summarizes the univariate and multivariate calculated hazard ratios that were included in the model. It appears that the effect of CCBs remains significant after adjusting for the NCCN prognostic class, the age, the gender, the performance status, the year of diagnosis, the CD34 level calculated by flow cytometry and the response to treatment. Hazard ratio for dying when being on a CCB is 1.39 in the proportional hazards model (95% CI 1.05-1.80, p=0.02).

Table 2. Survival data.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | p | HR (95%CI) | p | |

| NCCN prognostic group: | 2.72 (2.00-3.78) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.40-2.69) | <0.001 |

| •intermediate/good | 2.01 (1.71-2.35) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.71-2.37) | <0.001 |

| •poor/intermediate | ||||

| Age>60 | 2.13 (1.83-2.48) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.30-1.81) | <0.001 |

| PS>1 | 1.80 (1.49-2.16) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.28-1.89) | <0.001 |

| CD34>median | 1.23 (1.06-1.42) | 0.005 | 1.07 (0.91-1.25) | 0.379 |

| Male gender | 1.02 (0.88-1.18) | 0.779 | 1.00 (0.86-1.17) | 0.952 |

| Year of Diagnosis | 1.13 (0.96-1.33) | 0.12 | 1.08 (0.91-1.28) | 0.359 |

| •2000-2003/2004-2008 | 1.34 (1.09-1.66) | <0.001 | 1.22 (0.97-1.53) | 0.07 |

| •2004-2008/2009-2012 | ||||

| Response to treatment | 7.47 (5.22-10.44) | <0.001 | 6.97 (4.69-10.06) | <0.001 |

| •Died/poor | 3.17 (2.7-3.72) | <0.001 | 2.35 (1.97-2.80) | <0.001 |

| •Poor/complete | ||||

| CCBs | 1.6 (1.22-2.06) | <0.001 | 1.39(1.05-1.80) | 0.02 |

Discussion

In the current study we studied the effect of beta blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs and CCBs on the survival of patients with AML without including the patients with promyelocytic leukemia. We collected data on 1043 patients with AML who were diagnosed and treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2000 to 2012. We found that the NCCN prognosis classification as described in the NCCN guidelines for AML separates patients into three distinct prognostic groups. We found that older age, poor performance status, response to treatment, earlier year of diagnosis and high CD34 flow cytometry count were additional negative prognostic factors. Patients who were treated with beta blockers or ACE inhibitors or ARBs did not have a differently improved outcome compared to the patients who were not treated with such agents. On the contrary, patients who received CCBs had shorter overall survival compared to the patients who were not treated with CCBs even after adjusting for the NCCN prognostic classification, age, PS, year of diagnosis, response to treatment and CD34 flow cytometry count.

It is unclear why beta blockers and ACEi/ARBs were not found to interfere with survival in our cohort. It is likely that additional non measured confounders which might be present in patients but not in the in vitro experiments account for the discrepancy between the preclinical data and our findings. Furthermore, beta blockers and ACEi/ARBs do not interfere with pharmacokinetics and are therefore unlikely to enhance or attenuate the effects of chemotherapy.

Different mechanisms might account for the effect of CCBs on overall survival. First, it is plausible that treatment with CCBs is an indication of cardiovascular comorbidities as these agents are often used for the treatment of common conditions like hypertension, arrythmias or angina. The worse survival of patients on CCBs might reflect that this group of patients is sicker compared to the rest of the study population. Nonetheless, we did not see the same effect in patients who were treated with other antihypertensives like beta blockers and ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Both classes of medications are often used in patients with congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease. Beta blockers in particular are used to alleviate angina and treat various arrythmias. In addition, amlodipine is not indicated for the treatment of arrhythmia or angina; however the effect of amlodipine on the survival of patients with AML was similar to the effect of diltiazem indicating a class effect rather than a confounding effect from underlying coronary artery disease.

A second possibility might be interference with the pharmacokinetics of chemotherapy or of drugs that are used as supportive treatment like azoles for prophylaxis or treatment of fungal infections. Nevertheless, diltiazem is a notorious inhibitor of the P450 enzyme[27] which is central in the metabolism of many drugs and would enhance the effect of chemotherapy or supportive treatment that is processed by P450 in the liver. On the other hand, amlodipine does not interfere with P450 although patients on amlodipine had the same survival as did patients on diltiazem, which was inferior compared with patients who were on neither of these drugs.

The effect of CCBs on calcium homeostasis at the level of the tumor microenvironment is another potential explanation for the negative effect of CCBs on survival of patients with AML. The effect of calcium channel blockers on apoptosis inhibition that might make a putative connection to carcinogenesis is controversial and would require a dose higher than the typical prescription dose[28]. Some studies suggest that calcium channel blockers or lowering the intracellular levels of calcium abrogates apoptotic signals[29, 30] whereas others have reported that low calcium levels can mediate apoptosis[31] or that calcium channel blockers can enhance the apoptotic effect of chemotherapy[32]. Both types of results though would support the premise of benefiting the patients as they are referring to different cancerous and non-cancerous settings; this might represent some level of publication bias in the literature that covers the effect of intracellular calcium and calcium channel blockers on apoptosis.

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest cohorts of patients with AML, including apopulation treated at a single center. Furthermore, we here have validated the NCCN prognostic classification and have included this classification in the proportional hazards model. According to the NCCN algorithm, patients with AML are classified into good, intermediate or poor prognosis on the basis of the traditional cytogenetic analysis with the addition of the presence or absence of certain mutations; patients with normal cytogenetics and either NPM1 but no FLT3-ITD mutation either an isolated bi-allelic CEBPA mutation are re-classified as favorable from intermediate risk; patients with favorable cytogenetics and c-kit mutation are re-classified to intermediate risk and finally the presence of FLT3-ITD mutations in the setting of normal cytogenetics predicts worse prognosis.

This study has several limitations: first, it is an observational, retrospective study that is subject to bias. Second, we did not adjust the results for the different treatments that the patients received. This is partially balanced by the adjustment for response; regardless of the treatment type, the negative effect of CCBs on survival of patients with AML was independent of whether the patients died during treatment, achieved only a partial response or experienced a complete response. It is expected that most of the patients received induction chemotherapy followed by consolidation therapy or high dose chemotherapy followed by a bone marrow transplant as per standard institutional practices. Third, we have not adjusted the effect of CCBs on survival for cardiologic comorbidities, especially for angina or arrhythmia as the indication for CCBs that might confound the results. It is possible that comorbidities are more common among patients on antihypertensive medication and this might account for the observed associations with survival. In addition, although we reasonably presume that patients who have been on antihypertensive medications would continue taking them during therapy for AML, it is possible that in some patients antihypertensives were discontinued in the case of hypotension or septic shock.

In summary, here we present the effect of beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors or ARBs on the prognosis of AML. We show that patients on amlodipine or diltiazem have shorter survival independently of other known prognostic factors. The etiology of this phenomenon is unclear; further research should be focused on the interaction of CCBs with the calcium homeostasis in the microenvironment of patients with AML.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank pharmacists including Deborah McCue for providing the comprehensive pharmacological data that enabled this study. They are also indebted to the physicians of the leukemia department that treated the patients reported here.

Grant support: This study was supported by a grant from the ASCO Young Investigator Award (to YKC) and, in part, supported by fundings from NCI (CA55164, CA100632) and the Haas Chair in Genetics (to MA).

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information is available at the Leukemia's website

References

- 1.Ferrara F, Schiffer CA. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adults. Lancet. 2013;381:484–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer K, Scholl C, Salat J, et al. Design and validation of DNA probe sets for a comprehensive interphase cytogenetic analysis of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1996;88:3962–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mrozek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, Whitman SP, Bloomfield CD. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood. 2007;109:431–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltzman BS, Weiss NS, Sieh W, et al. Use of antihypertensive medications and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:365–71. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay L, Assimes TL, Yin H, Bartels DB, Schiffrin EL, Suissa S. Long-term use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mc Menamin UC, Murray LJ, Cantwell MM, Hughes CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in cancer progression and survival: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:221–30. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barron TI, Connolly RM, Sharp L, Bennett K, Visvanathan K. Beta blockers and breast cancer mortality: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2635–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemeshow S, Sorensen HT, Phillips G, et al. beta-Blockers and survival among Danish patients with malignant melanoma: a population-based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2273–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aksu S, Beyazit Y, Haznedaroglu IC, et al. Over-expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD 143) on leukemic blasts as a clue for the activated local bone marrow RAS in AML. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:891–6. doi: 10.1080/10428190500399250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, et al. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De la Iglesia Inigo S, Lopez-Jorge CE, Gomez-Casares MT, et al. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cell lines treated with captopril, trandolapril and losartan: a new role in the treatment of leukaemia for these agents. Leuk Res. 2009;33:810–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanojkovic TP, Zizak Z, Mihailovic-Stanojevic N, Petrovic T, Juranic Z. Inhibition of proliferation on some neoplastic cell lines-act of carvedilol and captopril. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 2005;24:387–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajighasemi F, Mirshafiey A. In vitro sensitivity of leukemia cells to propranolol. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2009;1:144–9. doi: 10.4021/jocmr2009.06.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz A. Molecular and cellular aspects of calcium channel antagonism. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:6F–8F. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa T, Nukada T, Suzuki K, et al. Voltage and pH dependent block of cloned N-type Ca2+ channels by amlodipine. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1136–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogeski I, Kilch T, Niemeyer BA. ROS and SOCE: recent advances and controversies in the regulation of STIM and Orai. J Physiol. 2012;590:4193–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stepien O, Marche P. Amlodipine inhibits thapsigargin-sensitive CA(2+) stores in thrombin-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1220–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Z, Li H, Guo F, et al. Egr-1, the potential target of calcium channel blockers in cardioprotection with ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:17–24. doi: 10.1159/000227809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: new roles for known actors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:609–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Xiao J, Adachi M, Liu Z, Zhou J. 4-aminopyridine induces apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia cells via increasing [Ca2+]i through P2X7 receptor pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28:199–208. doi: 10.1159/000331731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Xu B, White RE, Lu L. Growth factor-mediated K+ channel activity associated with human myeloblastic ML-1 cell proliferation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1657–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu ZZ, Li DP, Chen SR, Pan HL. Aminopyridines potentiate synaptic and neuromuscular transmission by targeting the voltage-activated calcium channel beta subunit. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36453–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdullaev IF, Bisaillon JM, Potier M, Gonzalez JC, Motiani RK, Trebak M. Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2008;103:1289–99. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000338496.95579.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanamandra N, Buzzeo RW, Gabriel M, et al. Tipifarnib-induced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma cells depends on Ca2+ influx through plasma membrane Ca2+ channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:636–43. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Donnell MR, Abboud CN, Altman J, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2012;10:984–1021. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou SF. Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:310–22. doi: 10.2174/138920008784220664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason RP. Calcium channel blockers, apoptosis and cancer: is there a biologic relationship? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1857–66. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trump BF, Berezesky IK. Calcium-mediated cell injury and cell death. FASEB J. 1995;9:219–28. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang F, Schulte BA, Qu C, Hu W, Shen Z. Inhibition of the calcium- and voltage-dependent big conductance potassium channel ameliorates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in spiral ligament fibrocytes of the cochlea. Neuroscience. 2005;135:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leszczynski D, Zhao Y, Luokkamaki M, Foegh ML. Apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Protein kinase C and oncoprotein Bcl-2 are involved in regulation of apoptosis in non-transformed rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1265–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo S, Yin D, Morimura T, Takeuchi J. Combination therapy with cisplatin and nifedipine inducing apoptosis in multidrug-resistant human glioblastoma cells. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:469–74. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.3.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.