Abstract

Objectives

Bipolar disorder (BD) has been associated with dysfunctional brain connectivity and with family chaos. It is not known whether aberrant connectivity occurs before illness onset, representing vulnerability for developing BD amidst family chaos. We used resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine neural network dysfunction in healthy offspring living with parents with BD and healthy comparison youth.

Methods

Using two complementary methodologies [data-driven independent component analyses (ICA) and hypothesis-driven region-of-interest (ROI)-based intrinsic connectivity], we examined resting state fMRI data in 8–17-year-old healthy offspring of a parent with BD (n = 24, high risk) and age-matched healthy youth without any personal or family psychopathology (n = 25, low risk).

Results

ICA revealed that relative to low-risk youth, high-risk youth showed increased connectivity in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) subregion of the left executive control network (ECN), which includes frontoparietal regions important for emotion regulation. ROI-based analyses revealed that high-risk versus low-risk youth had decreased connectivities between left amygdala and pregenual cingulate, between subgenual cingulate and supplementary motor cortex, and between left VLPFC and left caudate. High-risk youth showed stronger connections in the VLPFC with age and higher functioning, which may be neuroprotective, and weaker connections between the left VLPFC and caudate with more family chaos, suggesting an environmental influence on frontostriatal connectivity.

Conclusions

Healthy offspring of parents with BD show atypical patterns of prefrontal and subcortical intrinsic connectivity that may be early markers of resilience from or vulnerability for developing BD. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether these patterns predict outcomes.

Keywords: amygdala, bipolar, functional connectivity, resting state, risk, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a highly familial disorder. Twin and family studies have reported a 59–87% heritability of BD (1), reflecting the high level of risk for first-degree relatives of probands with BD to develop the disorder themselves (2). Children of parents with BD are especially vulnerable to developing mood problems at an early age and more commonly have a severe course of illness (3, 4), signifying the importance of elucidating factors that predict the early onset of BD. Indeed, assessing familial risk can improve identification of bipolar symptom onset in youth (5), and combining this with a biological assessment is likely to increase the accuracy of predicting outcome in high risk youth (6), while also providing insights about the timing and mechanisms of risk for developing BD.

BD is principally characterized by disruptions in prefrontal and subcortical neural networks (7–9). Findings from task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in youth who have already developed BD have demonstrated either over- or under-activation of prefrontal emotion regulatory regions (10) or limbic hyperactivity (11–13). However, it is unclear from these studies whether the observed neural dysfunction precedes or is a consequence of bipolar illness. Evidence from youth at risk for BD who have not fully developed BD suggest certain patterns of aberrant neural activations in key prefrontal and limbic regions including the ventromedial and ventrolateral (VLPFC) prefrontal cortices, the striatum, and the amygdala (14–18) and impairments in neurocognitive performance (19–22) that may precede BD onset. Most of these studies have been limited, however, by symptom or illness-related confounds such as mood state, comorbidities, and medication exposure (10–12, 23–25), and have reported activations in discrete brain regions rather than the functional interactions among them. Nevertheless, taken together, these studies raise the possibility that disruption of connections among different neural regions that constitute large-scale networks (26) may represent early risk factors for developing BD.

It is also well-established that offspring of parents with BD are biologically sensitive to stress (27), are exposed to significant adversity or negative life events (28), and typically live in family environments that have low levels of cohesion and organization, and high levels of conflict and chaos (29–31). Importantly, however, it is not known whether exposure to such dysfunctional family settings is associated with disruptions in neural circuitry in these high-risk youth. Further, unaffected siblings of individuals with BD have been found to show greater levels of impulsivity compared to healthy controls (32) that appears to be compounded by a chaotic family environment and poor psychosocial functioning (33, 34). However, not all youth at familial risk for BD go on to develop BD, suggesting that some youth may be resilient to the mechanisms by which BD is transmitted (35). Examining healthy offspring of parents with BD provides a unique opportunity to simultaneously evaluate factors associated with risk and resilience, and to examine associations between neural network function and specific intrinsic (e.g., poor inhibitory control) or environmental (e.g., family chaos), as opposed to acute illness-associated (36) factors that precede symptom onset.

A viable approach to characterizing neural network risk factors for developing BD is to examine resting state or intrinsic functional connectivity of neural circuits that subserve emotional and inhibitory control in healthy youth at risk for BD. Resting state fMRI has several advantages over task-based fMRI. First, resting state fMRI circumvents task-related confounds and is easy to administer. Second, it probes ongoing spontaneous brain activity that reflects neural processes that consume the vast majority of the brain's resources, offering a potentially richer source of signal changes (37) that may be implicated in risk for developing BD. Finally, resting state fMRI can provide information about the formation and strength of neural networks during critical periods of vulnerability for the development of mood syndromes (38). Adults with BD have been found to demonstrate decreased intrinsic functional connectivity between the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the amygdala, thalamus, and pallidostriatum (39), and a negative correlation between ventral prefrontal and amygdalar connectivity (40). Youth with BD have demonstrated greater negative resting state functional connectivity between the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and right superior temporal gyrus (41) and abnormal ventral-affective and dorsal-cognitive circuits compared to healthy subjects during rest (42). Youth with BD have also shown hyperconnectivity between the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and affective and executive control network (43). Further, greater connectivity of the right amygdala within the affective network is associated with better executive function in children with BD but not in controls (43). These findings suggest that disrupted functional connectivity in the brain regions that subserve emotional and cognitive functioning underlies core deficits that characterize BD across the lifespan.

To date, no study has examined intrinsic functional connectivity in youth with a familial vulnerability for BD and who have not yet experienced any mood symptoms or other psychiatric disorders. Drawing on findings from neural examinations of youth at risk for BD (14–18) and studies of resting state fMRI in adults (39, 40) and in youth with BD (41–43), we predicted that, compared with healthy youth of never-disordered parents, healthy youth of parents with bipolar I disorder would exhibit atypical patterns intrinsic functional connectivity between key prefrontal and subcortical brain regions and networks associated with emotion regulation, including the VLPFC, ACC, and amygdala. In addition, we hypothesized that a chaotic family environment and poorer functioning would be associated with more disrupted connectivity within the high-risk group.

Methods and materials

Participants

The Stanford University Panel of Medical Research in Human Subjects approved this research protocol. Participants included 49 youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years with no current or past Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–IV) Axis I disorder. Twenty-four youth had at least one biological parent diagnosed with bipolar I disorder (high risk), and 25 youth had biological parents and first- and second-degree relatives with no history of any Axis I disorder (low risk). Youth were recruited with their parents through advertisements in the local community and through clinics in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. The parents’ responses to a telephone interview established that the family was fluent in English and that their children were between 8 and 17 years of age and were unlikely to have past or current psychopathology. Other exclusion criteria for all subjects included a neurological condition (such as a seizure disorder), a substance use disorder, IQ < 80, or presence of metallic implants or braces. Eligible youth were invited to the laboratory for more extensive interviews and testing after the parents completed a written informed consent, and the children completed a written assent.

Assessment of psychological health

All participants were ruled out for psychiatric disorders by semi-structured clinical interviews using the Affective Modules of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U KSADS) (44) and the Kiddie Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version (KSADS-PL) (45) by raters with established symptom and diagnostic reliability (kappa > 0.9). Masters-level and higher interviewers with training and experience administered the interview separately to youth and their parents (about the youth) in order to rule out current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses for affective, psychotic, anxiety, behavioral, substance abuse, and eating disorders. A different interviewer administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM–IV (SCID) (46) to the parents while they were euthymic to establish a bipolar I disorder diagnosis in high-risk group parents and to rule out any psychiatric disorders in the parents of the low-risk group. This diagnostic information was supplemented by a Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) (47) to assess levels of parent psychopathology. A board-certified child psychiatrist (MKS) ultimately made all diagnostic decisions.

To ensure that the two groups did not differ in levels of mania or depressive symptoms, all youth were interviewed using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (48) and the Children’s Depressive Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) (49). Levels of anxiety were assessed by administering the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) (50) to the parents. Global functioning was determined by the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) (51). Level of problematic family functioning was assessed by the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES) IV (52) administered to all parents while they were euthymic. Most relevant to our hypotheses was the family chaos score, which indexes the degree of disorganization in the family environment that may adversely affect neural development in high-risk youth (53). Age, sex, socioeconomic status (Hollingshead Four Factor Index) (54), pubertal stage (Pubertal Development Scale) (55), IQ (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence) (WASI) (56), and handedness (Crovitz Handedness Questionnaire) (57) were also assessed.

fMRI data acquisition and preprocessing

Magnetic resonance images were collected at Lucas Center of Radiology at Stanford University using a 3T GE Discovery MR750 scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee) with a 16-channel whole head coil, T2-weighted spiral in/out pulse sequence: repetition time (TR) = 2000 msec, echo time (TE) = 30 msec, flip angle = 80°, field of view (FOV) = 220 mm × 220 mm, voxel-size = 3.43 mm × 3.43 mm × 4 mm with 1 mm skip, 30 slices collected in ascending order, anterior and posterior commissure alignment, 210 volumes. Subjects were scanned for seven min while instructed to remain awake, but rest quietly with their eyes closed. Three-dimensional high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired using a spoiled gradient recall pulse sequence: TR = 8.5 msec, TE = 3.4 msec, flip angle = 15°; FOV = 220 mm × 220 mm, voxel-size 0.86 × 0.86 × 1.5mm, 1-NEX (number of excitation) scans, 124 coronal slices.

Image preprocessing was performed using the Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library (FSL version 5.0.2; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). The following preprocessing steps were applied to the functional data: (i) first six volumes were discarded to allow for signal stabilization; (ii) head motion correction was performed using the Motion Correction FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (MCFLIRT) (58); (iii) non-brain tissue was extracted using the Brain Extraction Tool (BET) (59); (iv) spatial smoothing was conducted using a Gaussian kernel of 6-mm full width half maximum; (v) high-pass temporal filtering (Gaussian-weighted least mean squares straight line fitting with sigma = 75 seconds) was applied to the data; and (vi) low-pass temporal filtering (half width at half maximum of 2.8 secs) was applied to the data. After preprocessing, the functional data were registered to each individual’s high-resolution T1-weighted image, followed by registration to the MNI152 standard-space by affine linear registration using FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT) (58).

Several sources of noise were regressed from the functional data, including six motion parameters and time-series extracted from the white matter and cerebrospinal fluid. Importantly, high and low-risk groups did not differ on the six motion parameters (x: p = 0.81; y: p = 0.25; z: p = 0.13; pitch: p = 0.10; roll: p = 0.58; yaw: p = 0.35). Two high-risk and one low-risk subjects were excluded due to excessive motion (defined as scans where maximum translation or rotation exceeded more than one volume containing motion above 2 mm or 2 degrees, respectively). Recent work has shown that in addition to regressing out motion parameters, it is important to detect and remove individual motion-affected volumes to avoid spurious connectivity results (60, 61). Thus, volumes affected with excessive or sharp motion were detected using the fsl_motion_outliers script (supplied with FSL) and were regressed out as confounding variables. This alternative approach of regressing affected volumes as opposed to simply removing them is preferred because it adjusts for the changes in signal and auto-correlation on either side of the affected volume and also appropriately corrects for the degrees of freedom. Further, volumes identified as motion outliers were not significantly different between groups (high-risk: 4.70% ± 3.10%, low-risk: 4.95% ± 2.33%; t = 0.320, p = 0.75). Finally, the residual image was scaled for further analysis.

Group independent component analysis (ICA) and dual regression

After preprocessing, group ICA and dual regression procedures were used to assess between group differences in resting-state functional connectivity (62). They involve three steps: (i) data-driven spatial maps are created by running group ICA (58) on temporally concatenated data from both groups. Using this technique we decomposed the data into 25 components; (ii) using all of the 25 components, we ran dual regression (first temporal, then spatial) to estimate subject specific spatial maps for each component (63, 64); and (iii) for selected a priori components (described below), we examined differences between high- and low-risk groups using subject-specific spatial maps, controlling for demeaned YMRS, CDRS-R, and MASC scores. To determine significant group differences, for each independent component spatially masked at Z = 4, we applied FSL’s randomise permutation (5000 iterations) tool (65, 66) using a threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) procedure at a family-wise error (p < 0.05). A post-hoc Bonferroni correction was then applied for testing four networks (p = 0.05/four networks) for a final adjusted p value of < 0.0125.

Selection of networks and region-of-interests (ROI)

Four out of the 25 group functional networks, including the dorsal and ventral default mode (DMN) and bilateral executive control (ECN) networks (67) (see Figure 1), were selected a priori for between-group analyses based on three observations: (i) individuals with and at risk for BD have significant deficits in emotion and executive functioning and regulation (68, 69) that are subserved by interfacing prefrontal (VLPFC and DLPFC) and parietal regions included in these networks; (ii) individuals with BD and their relatives have demonstrated atypical patterns of connectivity in regions associated with the DMN and ECN compared to healthy subjects (70–73); and (iii) the ECN and DMN show inverse connectivity that may reflect opposing network functions during self-referential thinking and the regulation of emotion (74, 75). We also investigated connectivity in the following ROIs selected a priori and created from the Harvard–Oxford atlas: left and right amygdala, left and right VLPFC, and the subgenual anterior cingulate. These regions were selected because of their consistent representation in rest- and task-related fMRI studies of BD, and because they subserve attention, inhibitory control, and emotion regulation (14–16, 41, 42, 76–78).

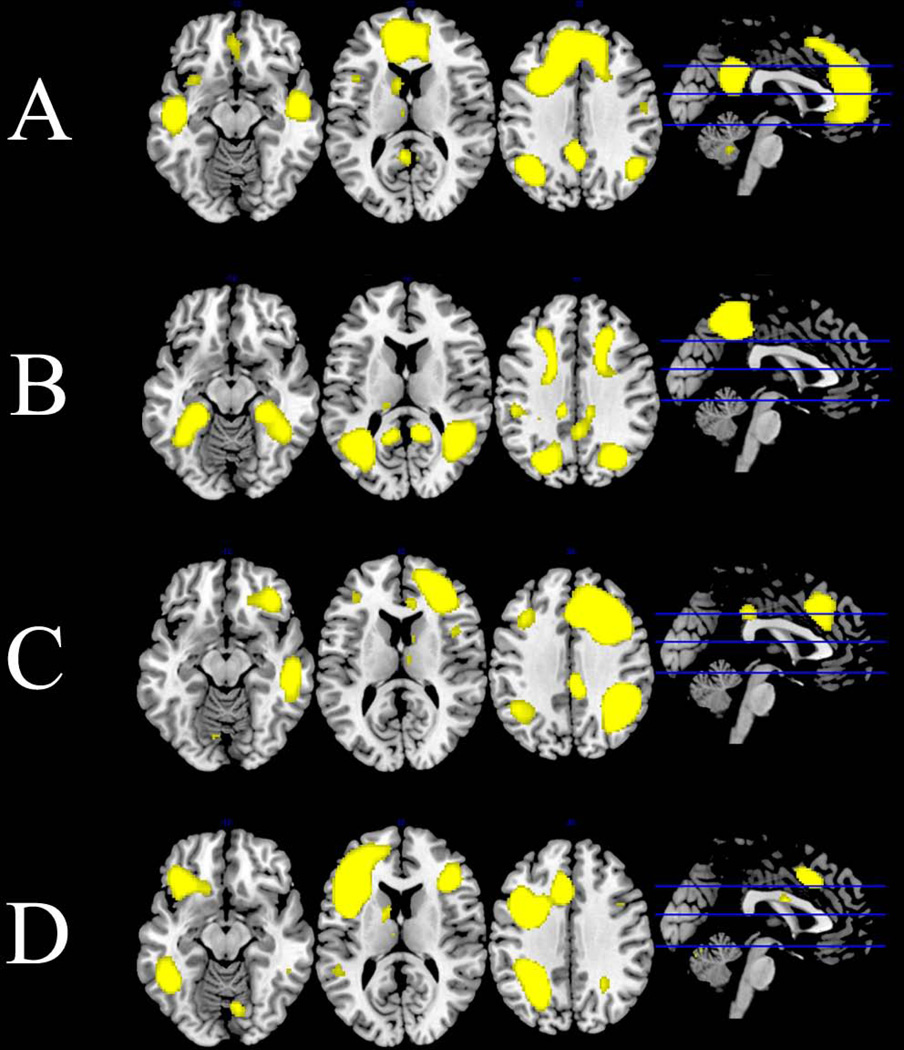

Fig. 1.

Default mode and executive control networks derived from group independent components analysis of all subject overlaid on anatomical template: (A) default mode network; (B) ventral default mode network; (C) right executive control network; (D) left executive control network. All networks are at the Z = 4 threshold applied to group-level statistics.

ROI-based connectivity analysis

To complement the ICA analysis, we conducted a hypothesis-driven connectivity analysis (79) to explore whole-brain connectivity in three a priori regions that have shown aberrant activations in task-based fMRI studies in youth at risk for BD. Anatomical ROIs were used to extract averaged time series from residual images created by the preprocessing steps described above. Extracted time series of a priori ROIs were modeled with regression analysis [using the FMRI Expert Analysis Tool (FEAT)] to estimate the ROI connectivity maps for each subject. To account for the common variance associated with laterality, left and right ROIs were orthogonalized within the amygdala and VLPFC. Thus, after orthogonalization, any signal shared by left and right ROIs is attributed solely to either the left or right ROI. Group-level analyses were conducted on the resulting connectivity maps while controlling for demeaned YMRS, CDRS-R, and MASC scores. FSL’s randomise permutation (5000 iterations) tool was applied with threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) procedure with a threshold of p < 0.05, family-wise error corrected. In addition, effect size for distinguishing between the two groups for each of the ROIs was calculated using Cohen’s d (80).

Relations to cumulative intrinsic and environmental factors

We extracted connectivity estimates from the clusters showing group-level differences in the group ICA and ROI-based connectivity analyses in order to examine correlates of aberrant connectivity. We conducted partial correlations, adjusting for YMRS, CDRS-R, and MASC scores, between connectivity estimates and cumulative intrinsic and environmental characteristics, including age, gender, measures of global functioning, and chaotic family structure within each group. We then conducted Fisher’s r-to-z transformations to determine whether the high- and low-risk groups differed significantly with respect to these within-group correlations. In addition, the extracted connectivity estimates and demographics were entered into a univariate analysis to determine group by gender interactions.

Results

Participants

Demographic information is presented in Table 1. High- and low-risk groups were balanced for age, gender, handedness, IQ, and pubertal stage. Moreover, the groups did not differ in scores on the CDRS-R, YMRS, or MASC (all p > 0.05). Compared with the low-risk group, the high-risk group had significantly lower CGAS scores (t = 2.11, p = 0.04), higher family chaos scores (t = 2.8, p = 0.008), and higher parental SCL-90 scores (t = −5.07, p < 0.001). There were no significant group-by-gender interactions for age, handedness, IQ, pubertal stage, CGAS, CDRS-R, YMRS, or MASC scores. However, family chaos scores had a significant group-by-gender interaction (F = 4.38, p = 0.043), driven by higher scores in high-risk females compared to high-risk males (t = 2.428, p = 0.027). Family chaos scores were not correlated with parental SCL-90 scores.

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral variables of study sample

| Variables | High risk (n = 24) |

Low risk (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 12.25 (3.03) | 11.56 (2.29) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 16 (66.67) | 15 (60) |

| Right handedness, n (%) | 22 (91.67) | 24 (96) |

| Tanner stage, mean (SD) | 2.64 (0.73) | 2.31 (0.81) |

| Caucasian race, n (%) | 21 (87.5) | 18 (72) |

| Full-scale IQ, mean (SD) | 114.69 (10.71) | 114.88 (17.30) |

| YMRS score, mean (SD) | 1.33 (1.37) | 1.08 (1.24) |

| CDRS-R score, mean (SD) | 19.67 (3.16) | 19.25 (2.56) |

| CGAS score, mean (SD)a | 87.00 (5.51) | 90.36 (5.49) |

| MASC t-score, mean (SD) | 42.26 (14.55) | 45.27 (10.92) |

| Family chaos score, mean (SD)a | 15.11 (3.42) | 12.25 (3.17) |

| Parental Symptom Checklist-90, mean (SD)a | 39.18 (27.85) | 8.08 (9.72) |

SD = standard deviation; IQ = intellectual quotient; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; CDRS-R = Children’s Depressive Rating Scale-Revised; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children.

p < 0.05.

Group ICA

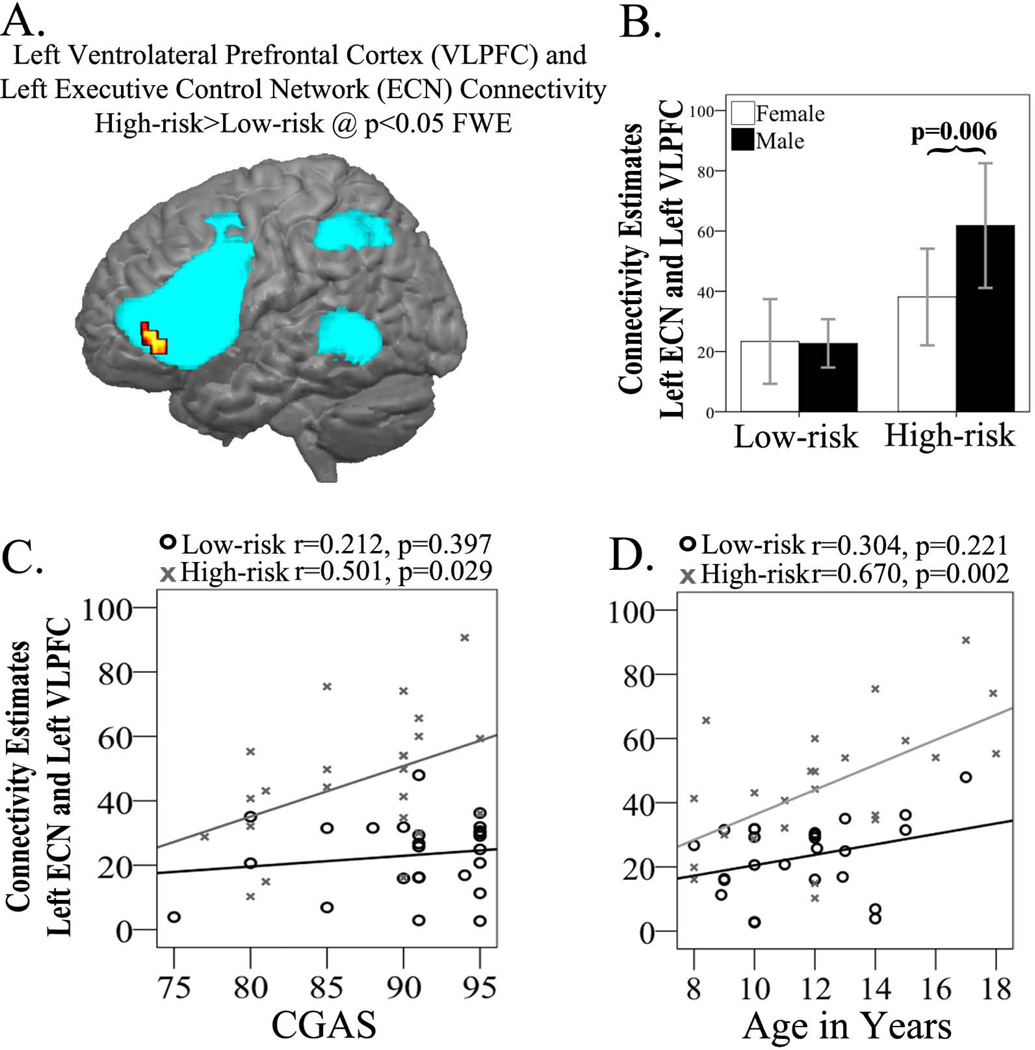

Results of the group ICA showed that among the four networks of interest, the high-risk group had greater connectivity in the left ECN, in particular in the VLPFC area, than did the low-risk group (Fig. 2, Table 2); the two groups did not differ in connectivity in the other three networks. There were no networks for which the low-risk youth had greater functional connectivity than the high-risk youth. However, a significant group by gender interaction (F = 4.445, p = 0.042) indicated that the high-risk males had greater connectivity (t = −3.03, p = 0.006) in the VLPFC area of left ECN than high-risk females. These gender differences were not observed in the low risk group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Group independent components analysis (ICA) results in the high-risk and low-risk groups. (A) Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) cluster showing high-risk > low-risk connectivity differences overlaid upon the left executive control network. (B) Extracted connectivity measures from the left VLPFC show high-risk males with increased connectivity (p = 0.006) compared to high-risk females. (C) Positive correlation (r = 0.501, p = 0.029) in the high-risk group between VLPFC connectivity estimates and Clinical Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) scores. (D) Positive correlation (r = 0.670, p = 0.002) in the high-risk group between VLPFC connectivity estimates and age. ECN = executive control network; FEW = family-wise error.

Table 2.

Significant between group differences in resting state functional connectivity

| Network | Comparison | Region | Cluster size (mm3) | MNI coordinates | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Group-based ICA | |||||||

| Left executive control |

High–Risk > Low–Risk |

Left VLPFC | 448 | −42 | 42 | −4 | 0.008 |

| ROI-based connectivity analysis | |||||||

| Left amygdala |

Low–Risk > High–Risk |

Pregenual cingulate | 344 | 0 | 38 | 2 | 0.024 |

| Subgenual cingulate |

Low–Risk > High–Risk |

Right supplementary motor cortex |

560 | 10 | −6 | 68 | 0.031 |

| Left VLPFC | Low–Risk > High–Risk |

Left caudate | 832 | −14 | −4 | 22 | 0.025 |

| Left VLPFC | High–Risk > Low–Risk |

Left superior parietal lobule |

64 | 22 | −42 | 72 | 0.048 |

MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute; ICA = independent component analysis; ROI = region-of-interest; VLPFC = ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

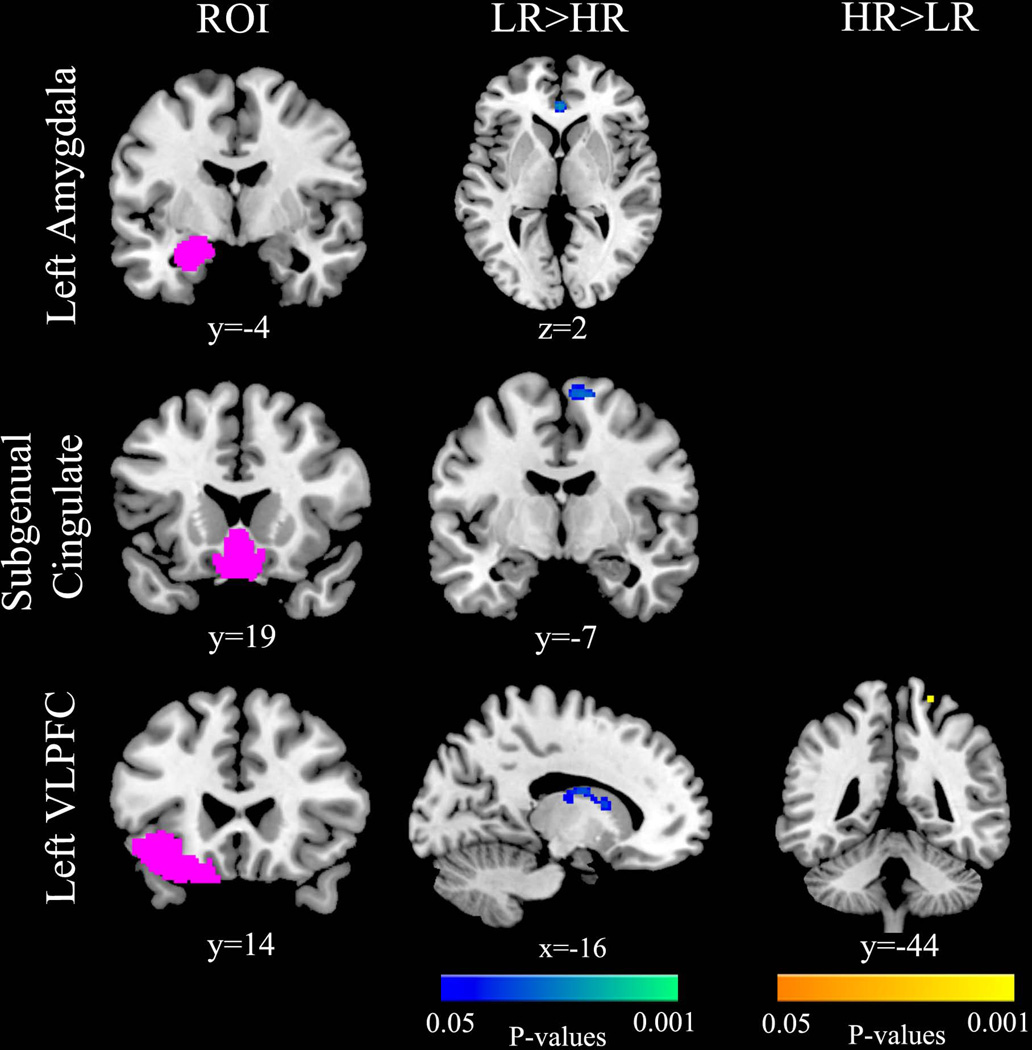

ROI-based connectivity

In the ROI connectivity analyses, the low-risk group had greater connectivity than did the highrisk group between the left amygdala and pregenual cingulate [t(47) = 2.02, p = 0.024, Cohen’s d = 0.58], the subgenual cingulate and the supplementary motor cortex [t(47) = 1.91, p = 0.031, Cohen’s d = 0.56], and the left VLPFC and left caudate [t(47) = 1.91, p = 0.025, Cohen’s d = 0.56] (Fig. 3, Table 2); the high-risk group had greater connectivity than did the low-risk group between the left VLPFC and left superior parietal lobule [t(47) = −1.49, p = 0.048, Cohen’s d = −0.43] (Fig. 3, Table 2). The two groups did not differ significantly in connectivity estimates in the right amygdala or right VLPFC and there were no significant group by gender interactions in these analyses.

Fig. 3.

Region-of-interest (ROI) based connectivity results in the high-risk (HR) and low-risk (LR) groups. Compared to the low-risk group, the high-risk group had decreased connectivity between the left amygdala and the anterior cingulate, the subgenual cingulate and the right supplemental motor area, the left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) and the left caudate, and decreased connectivity between the left VLPFC and the left parietal cortex.

Correlational analyses

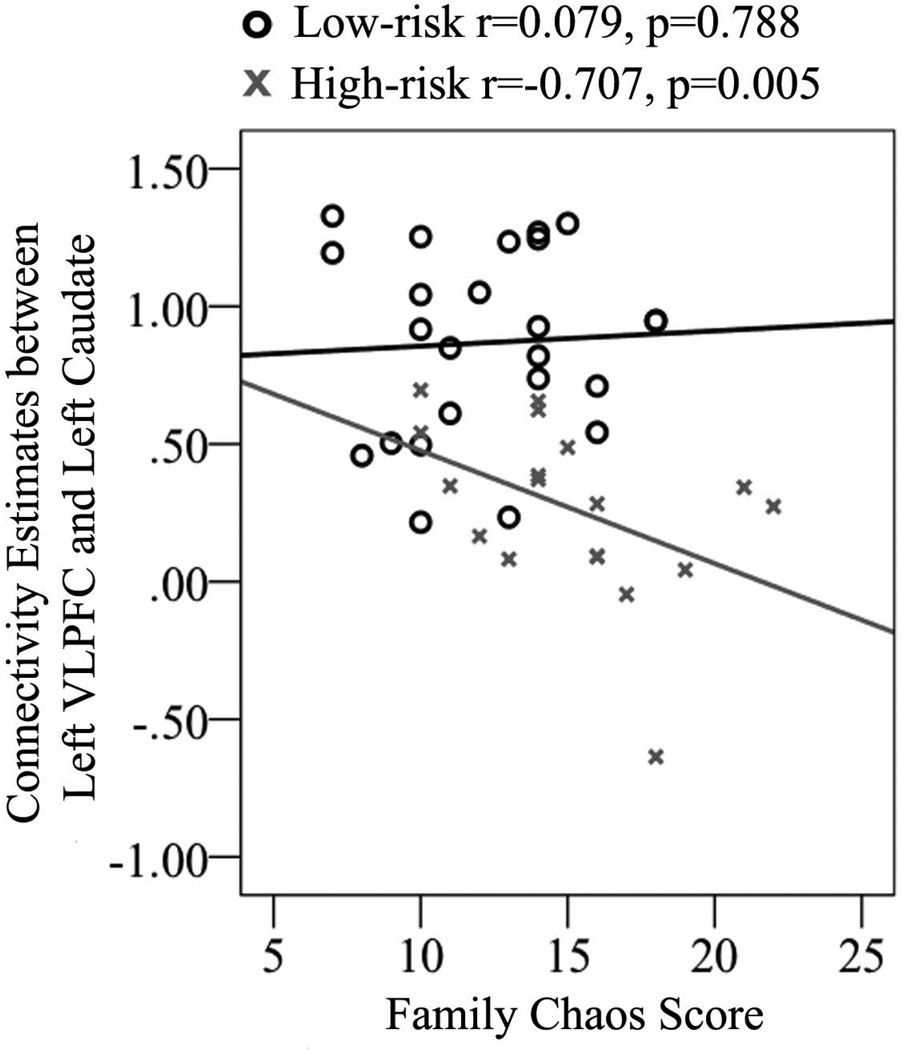

From the group ICA analysis, connectivity estimates in the left VLPFC area of ECN within the high-risk group was positively correlated with both age (r = 0.670, p = 0.002) and CGAS scores (r = 0.501, p = 0.029) (Fig. 2); these correlations were not significant within the low-risk group [age: (r = 3.04, p = 0.22; z = −1.63, p = 0.052); CGAS: (r = 0.212, p = 0.397; z = −1.1, p = 0.14)]. Moreover, ROI connectivity estimates between the left VLPFC and left caudate were positively correlated with age (r = 0.542, p = 0.014) within the high-risk group to a significantly greater extent than was the case within the low-risk group (r = −0.100, p = 0.692; z = −2.31, p = 0.021), and negatively correlated with level of family chaos within the high-risk group (r = −0.707, p = 0.005) to a significantly greater extent than was the case within the low-risk group (r = 0.079, p = 0.788; z = 3.15, p = 0.0016) (Fig. 4). When controlling for gender in the high-risk group, these correlations between connectivity estimates and CGAS (r = 0.641, p = 0.004) and family chaos (r = −0.600, p = 0.030) remained significant, while correlations with age were no longer significant. In addition, the correlation between left caudate connectivity measurements and family chaos also remained significant after controlling for parent SCL-90 scores, (r = −0.712, p = 0.014)

Fig. 4.

Correlation between family chaos and connectivity between the left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) and left caudate in high-risk (r = –0.707, p = 0.005) and low-risk (r = 0.079, p = 0.788) groups.

Discussion

This study was designed to examine differences in intrinsic functional connectivity between healthy youth at high- versus low-risk for developing bipolar I disorder to determine patterns of connectivity that may increase or decrease risk for developing BD. As predicted, compared to their low-risk peers, youth at high-risk for BD had altered patterns of intrinsic functional connectivity both within brain networks and between key prefrontal and subcortical brain regions. Specifically, as compared to low-risk controls, ICA-based analyses revealed that high-risk offspring had increased connectivity in the VLPFC area of the left ECN and ROI-based analyses revealed that highrisk offspring had decreased functional connectivity between the left VLPFC and left caudate, between the left amygdala and the pregenual cingulate, and between the subgenual cingulate and the supplementary motor cortex. Importantly, older and higher-functioning high-risk offspring showed stronger connectivity in the VLPFC region of left ECN, suggesting a potential neuroprotective mechanism that may prevent the onset of mood symptoms for these youth as they pass through adolescence. Older high-risk youth had stronger connectivity between the left VLPFC and caudate than did their younger peers, but had weaker connectivity between these regions with more family chaos. It is possible that low frontostriatal connectivity in high-risk youth represents a vulnerability marker for developing BD that is compounded by a chaotic family environment, whereas with increasing age, greater frontostriatal connectivity becomes neuroprotective. In summary, the profile of altered prefrontal-subcortical connectivity observed in youth at familial risk for BD provides an initial picture of the type of connectivity patterns that may underlie a vulnerability to or resilience from disordered emotional and inhibitory control associated with BD.

Using independent group ICA and ROI-based analytic methods, we found that high-risk offspring have increased connectivity in the VLPFC region of the left ECN. This increase in VLPFC-ECN connectivity was positively correlated with age and global functioning within the high-risk group. Given that the VLPFC may function to increase attentional and inhibitory control and mediate cognitive responses to negative emotions, it is possible that the VLPFC reinforces connectivity in the ECN in high-risk youth as an adaptive brain response to prevent disorder-related attentional dysfunction and emotion dysregulation (81). This formulation is supported by the developmental trajectory of high-level attentional and inhibitory control, which relies with age on the integrity of, and dynamic interactions between, core neurocognitive networks, including the ECN (82, 83). Importantly, resilient adult relatives of individuals with BD have shown increased functional coupling between the VLPFC and superior parietal lobule during a Stroop test similar to healthy counterparts, a connectivity not found in individuals with BD (81). Our findings suggest that increased functional connectivity in the VLPFC region of left ECN occurs early in neurodevelopment in youth at risk for BD, and becomes a marker for resilience after individuals reach adulthood and have passed the period of highest risk for developing BD.

Two meta-analyses of neurocognitive functioning in individuals with BD and their first degree-relatives suggest that executive functions such as response inhibition, verbal learning, and memory, subserved by the ECN are candidate bipolar endophenotypes (84, 85). In the absence of mood and attentional dysfunction, youth at risk for BD may be especially vulnerable to anomalous connectivity in the ECN and require reinforced connectivity beyond what would be expected without a familial risk for BD. A compensatory mechanism is similarly formulated in youth with BD, for whom hyperconnectivity in executive control and affective networks compared to controls may represent a neural mechanism for cognitive control of emotions (43). Indeed, several recent studies have demonstrated that functional connectivity within emotion regulation neural networks can distinguish individuals resilient from and susceptible to mood disorders (86–88), and that pharmacological interventions normalize aberrant connectivity in these networks in youth with BD (10, 89). These studies collectively support that ECN connectivity may represent either an early biological marker of resilience or a target for prevention or early intervention. Importantly, because all youth in our study did not have any significant mood symptoms, we did not evaluate for group differences in the salience network, which has robust connectivity to limbic and other subcortical regions, and functions to identify homeostatically relevant internal and external stimuli during conflict monitoring and interoceptive feedback. In contrast, the ECN is equipped to handle stimuli once it is identified, and provides response flexibility by exerting control over posterior sensorimotor representations and by maintaining relevant data until proper actions are selected (90). These ECN functions may be the most relevant and sensitive functions to discriminate vulnerability from resilience in our sample population.

ROI-based analyses provide preliminary evidence for decreased connectivity between key prefrontal (cingulate and VLPFC) and subcortical (caudate and amygdala) in high-risk youth that is consistent with neural findings in BD (39, 40, 76–78) and behavioral findings in healthy relatives of individuals with BD (20, 32). Given these similarities with connectivity patterns observed in individuals who have already developed BD and in task-based fMRI studies in individuals at risk for mood disorders (14, 88), decreased connectivities between prefrontal regulatory regions and subcortical regions may represent markers of vulnerability. The only other study to examine resting state fMRI in unaffected relatives of individuals with BD reported decreased network connectivity between fronto-occipital and anterior default mode networks and between meso-limbic and sensory-motor networks (73), similar to our ROI-based results. Longitudinal follow up of the high-risk youth would confirm which connectivity findings predict the onset of BD.

Finally, we found that family chaos is associated with reduced fronto-striatal connectivity in high-risk but not low-risk offspring. Importantly, this association was independent of levels of parental dysfunction. Although there is a rich literature on how experiential factors and stress exposure can shape the development and plasticity of neural circuits in humans and animals (93, 94), few studies have directly examined the impact of a chaotic family environment on brain function. The present study is the first to demonstrate the impact of this factor on neural connectivity in youth at risk for BD. The association between a disorganized family structure and disrupted fronto-striatal connectivity in high-risk youth motivates early family intervention to prevent the onset or progression of psychiatric symptoms in youth at familial risk for psychopathology (53, 95). Similarly, interventions targeted to increase fronto-striatal connectivity in high-risk youth may lead to more adaptive transitions into adulthood (96, 97).

In this study we present the first evidence that even before the onset of mood symptoms, youth at familial risk for BD exhibit anomalies in intrinsic functional brain connectivity. We document a prominent role of the VLPFC in the executive control network as an index of both normal and disordered functional connectivity; as suggested by other researchers (15, 17, 98–100), this structure may be a promising candidate for a biological marker of risk for BD development. We note here three main limitations of this study. First, we had a modest sample size; nevertheless, our results were consistent using multiple analytic approaches, suggesting robust connectivity differences between groups. Second, we did not correct for multiple comparisons for ROI-based connectivity analyses; these analyses were based on a priori hypotheses derived from the extant literature. Our primary interest in conducting these analyses was in exploring potential neural risk factors that should be further examined in future studies. Third, this was a cross-sectional study of a sample of healthy children at familial risk for BD who may have yet to pass through the risk period for developing BD. Thus, we are limited in the scope of the conclusions we can draw regarding precisely how the anomalies in intrinsic functional connectivity we found in these participants are related to the development of BD. It will be important in future research to examine whether the anomalous patterns of intrinsic functional connectivity documented here predict or protect youth from developing BD symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grants MH085919 (MKS) and MH74849 (IHG). The authors thank Meghan Howe, LCSW, Elizabeth Adams, Rosie Shoemaker, Erica Marie Sanders, and Jennifer Kallini for their assistance with assessment, recruitment, data collection, and data entry.

Footnotes

Disclosures

KDC receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, NIMH, and NARSAD; and has served as an unpaid consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Sunovion. AR has served as a consultant for Novartis. MKS, RGK, MS, and IHG report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Smoller JW, Finn CT. Family, twin, and adoption studies of bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2003;123C:48–58. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Martelon M, McKillop HN, Biederman J. Further evidence for robust familiality of pediatric bipolar I disorder: results from a very large controlled family study of pediatric bipolar I disorder and a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1328–1334. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang KD. Course and impact of bipolar disorder in young patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:e05. doi: 10.4088/JCP.8125tx7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sala R, Axelson D, Birmaher B. Phenomenology, longitudinal course, and outcome of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:273–289. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.11.002. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Algorta GP, Youngstrom EA, Phelps J, Jenkins MM, Youngstrom JK, Findling RL. An inexpensive family index of risk for mood issues improves identification of pediatric bipolar disorder. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:12–22. doi: 10.1037/a0029225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brietzke E, Mansur RB, Soczynska JK, Kapczinski F, Bressan RA, McIntyre RS. Towards a multifactorial approach for prediction of bipolar disorder in at risk populations. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leow A, Ajilore O, Zhan L, et al. Impaired inter-hemispheric integration in bipolar disorder revealed with brain network analyses. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houenou J, Frommberger J, Carde S, et al. Neuroimaging-based markers of bipolar disorder: evidence from two meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2011;132:344–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green MJ, Cahill CM, Malhi GS. The cognitive and neurophysiological basis of emotion dysregulation in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavuluri MN, Ellis JA, Wegbreit E, Passarotti AM, Stevens MC. Pharmacotherapy impacts functional connectivity among affective circuits during response inhibition in pediatric mania. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich BA, Vinton DT, Roberson-Nay R, et al. Limbic hyperactivation during processing of neutral facial expressions in children with bipolar disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8900–8905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603246103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett AS, Reiss AL, Howe ME, et al. Abnormal amygdala and prefrontal cortex activation to facial expressions in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:821–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavuluri MN, Passarotti AM, Harral EM, Sweeney JA. An fMRI study of the neural correlates of incidental versus directed emotion processing in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:308–319. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181948fc7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsavsky AK, Brotman MA, Rutenberg JG, et al. Amygdala hyperactivation during face emotion processing in unaffected youth at risk for bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim P, Jenkins SE, Connolly ME, et al. Neural correlates of cognitive flexibility in children at risk for bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mourão-Miranda J, Almeida JRC, Hassel S, et al. Pattern recognition analyses of brain activation elicited by happy and neutral faces in unipolar and bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:451–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts G, Green MJ, Breakspear M, et al. Reduced inferior frontal gyrus activation during response inhibition to emotional stimuli in youth at high risk of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladouceur CD, Diwadkar VA, White R, et al. Fronto-limbic function in unaffected offspring at familial risk for bipolar disorder during an emotional working memory paradigm. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2013. 5C:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glahn DC, Almasy L, Barguil M, et al. Neurocognitive endophenotypes for bipolar disorder identified in multiplex multigenerational families. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:168–177. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brotman MA, Skup M, Rich BA, et al. Risk for bipolar disorder is associated with face-processing deficits across emotions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1455–1461. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318188832e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belleau EL, Phillips ML, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Ladouceur CD. Aberrant executive attention in unaffected youth at familial risk for mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitney J, Howe M, Shoemaker V, et al. Socio-emotional processing and functioning of youth at high risk for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passarotti AM, Ellis J, Wegbreit E, Stevens MC, Pavuluri MN. Reduced functional connectivity of prefrontal regions and amygdala within affect and working memory networks in pediatric bipolar disorder. Brain Connect. 2012;2:320–334. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang K, Adleman NE, Dienes K, Simeonova DI, Menon V, Reiss A. Anomalous prefrontal-subcortical activation in familial pediatric bipolar disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:781–792. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh MK, Chang KD, Kelley RG, et al. Reward processing in adolescents with bipolar I disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mesulam MM. Large-scale neurocognitive networks and distributed processing for attention, language, and memory. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:597–613. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostiguy CS, Ellenbogen MA, Walker C-D, Walker EF, Hodgins S. Sensitivity to stress among the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a study of daytime cortisol levels. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2447–2457. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostiguy CS, Ellenbogen MA, Linnen A-M, Walker EF, Hammen C, Hodgins S. Chronic stress and stressful life events in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang KD, Blasey C, Ketter TA, Steiner H. Family environment of children and adolescents with bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:73–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belardinelli C, Hatch JP, Olvera RL, et al. Family environment patterns in families with bipolar children. J Affect Disord. 2008;107:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero S, Delbello MP, Soutullo CA, Stanford K, Strakowski SM. Family environment in families with versus families without parental bipolar disorder: a preliminary comparison study. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:617–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardo LE, Bearden CE, Barrett J, et al. Trait impulsivity as an endophenotype for bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:565–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bella T, Goldstein T, Axelson D, et al. Psychosocial functioning in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones SH, Bentall RP. A review of potential cognitive and environmental risk markers in children of bipolar parents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1083–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frangou S. Risk and resilience in bipolar disorder: rationale and design of the Vulnerability to Bipolar Disorders Study (VIBES) Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:1085–1089. doi: 10.1042/BST0371085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider MR, DelBello MP, McNamara RK, Strakowski SM, Adler CM. Neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:356–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox MD, Greicius M. Clinical applications of resting state functional connectivity. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NUF, et al. The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Lowe MJ, Dzemidzic M. Resting state corticolimbic connectivity abnormalities in unmedicated bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chepenik LG, Raffo M, Hampson M, et al. Functional connectivity between ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala at low frequency in the resting state in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;182:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickstein DP, Gorrostieta C, Ombao H, et al. Fronto-temporal spontaneous resting state functional connectivity in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Q, Zhong Y, Lu D, et al. Altered regional homogeneity in pediatric bipolar disorder during manic state: a resting-state fMRI study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu M, Lu LH, Passarotti AM, Wegbreit E, Fitzgerald J, Pavuluri MN. Altered affective, executive and sensorimotor resting state networks in patients with pediatric mania. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38:232–240. doi: 10.1503/jpn.120073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. Reliability of the Washington University in St Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.First MB. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID-I: clinician version, administration booklet. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale –preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973:9, 13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children’s depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984;23:191–197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olson D. FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: validation study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37:64–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miklowitz DJ, Chang KD. Prevention of bipolar disorder in at-risk children: theoretical assumptions and empirical foundations. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:881–897. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cirino PT, Chin CE, Sevcik RA, Wolf M, Lovett M, Morris RD. Measuring socioeconomic status: reliability and preliminary validity for different approaches. Assessment. 2002;9:145–155. doi: 10.1177/10791102009002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carskadon MA, Acebo C. A self-administered rating scale for pubertal development. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:190–195. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) San Antonio; Harcourt Brace & Company: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crovitz HF, Zener K. A group-test for assessing hand- and eye-dominance. Am J Psychol. 1962;75:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy K, Birn RM, Bandettini PA. Resting-state fMRI confounds and cleanup. Neuroimage. 2013;80:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 2005;360:1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beckmann CF, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Smith SM. Presented at the 15th Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jun, 2009. Group comparison of resting-state fMRI data using multi-subject ICA and dual regression; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayasaka S, Nichols TE. Validating cluster size inference: random field and permutation methods. Neuroimage. 2003;20:2343–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shirer WR, Ryali S, Rykhlevskaia E, Menon V, Greicius MD. Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:158–165. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nieto RG, Castellanos FX. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological functioning in patients with early onset schizophrenia and pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40:266–280. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schulze KK, Walshe M, Stahl D, et al. Executive functioning in familial bipolar I disorder patients and their unaffected relatives. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pomarol-Clotet E, Moro N, Sarró S, et al. Failure of de-activation in the medial frontal cortex in mania: evidence for default mode network dysfunction in the disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:616–626. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.573808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vargas C, López-Jaramillo C, Vieta E. A systematic literature review of resting state network--functional MRI in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teng S, Lu C-F, Wang P-S, et al. Classification of bipolar disorder using basal-ganglia-related functional connectivity in the resting state. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013:1057–1060. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2013.6609686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meda SA, Gill A, Stevens MC, et al. Differences in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging functional network connectivity between schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar probands and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12569–12574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu C-H, Ma X, Li F, et al. Regional homogeneity within the default mode network in bipolar depression: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu C-H, Li F, Li S-F, et al. Abnormal baseline brain activity in bipolar depression: a resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu C-H, Ma X, Wu X, et al. Resting-state abnormal baseline brain activity in unipolar and bipolar depression. Neurosci Lett. 2012;516:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shehzad Z, Kelly AMC, Reiss PT, et al. The resting brain: unconstrained yet reliable. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2209–2229. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anticevic A, Tang Y, Cho YT, et al. Amygdala connectivity differs among chronic, early course, and individuals at risk for developing schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frangou S. Brain structural and functional correlates of resilience to bipolar disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2011;5:184. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Supekar K, Menon V. Developmental maturation of dynamic causal control signals in higher-order cognition: a neurocognitive network model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uddin LQ, Supekar KS, Ryali S, Menon V. Dynamic reconfiguration of structural and functional connectivity across core neurocognitive brain networks with development. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18578–18589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4465-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bora E, Harrison BJ, Davey CG, Yücel M, Pantelis C. Meta-analysis of volumetric abnormalities in cortico-striatal-pallidal-thalamic circuits in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2012;42:671–681. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arts B, Jabben N, Krabbendam L, van Os J. Meta-analyses of cognitive functioning in euthymic bipolar patients and their first-degree relatives. Psychol Med. 2008;38:771–785. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cisler JM, James GA, Tripathi S, et al. Differential functional connectivity within an emotion regulation neural network among individuals resilient and susceptible to the depressogenic effects of early life stress. Psychol Med. 2013;43:507–518. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pompei F, Dima D, Rubia K, Kumari V, Frangou S. Dissociable functional connectivity changes during the Stroop task relating to risk, resilience and disease expression in bipolar disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;57:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang L, Paul N, Stanton SJ, Greeson JM, Smoski MJ. Loss of sustained activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in response to repeated stress in individuals with early-life emotional abuse: implications for depression vulnerability. Front Psychol. 2013;4:320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pavuluri MN, Passarotti AM, Harral EM, Sweeney JA. Enhanced prefrontal function with pharmacotherapy on a response inhibition task in adolescent bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1526–1534. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05504yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fornito A, Zalesky A, Bassett DS, et al. Genetic influences on cost-efficient organization of human cortical functional networks. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3261–3270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4858-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pedroso I, Lourdusamy A, Rietschel M, et al. Common genetic variants and gene-expression changes associated with bipolar disorder are over-represented in brain signaling pathway genes. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:689–695. doi: 10.1038/nn.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Korosi A, Naninck EFG, Oomen CA, et al. Early-life stress mediated modulation of adult neurogenesis and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2012;227:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Berk M, Malhi GS, Hallam K, et al. Early intervention in bipolar disorders: clinical, biochemical and neuroimaging imperatives. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rubia K, Smith AB, Woolley J, et al. Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:973–993. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Somerville LH, Hare T, Casey BJ. Frontostriatal maturation predicts cognitive control failure to appetitive cues in adolescents. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23:2123–2134. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Erol A, Kosger F, Putgul G, Ersoy B. Ventral prefrontal executive function impairment as a potential endophenotypic marker for bipolar disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:18–23. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.756062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hajek T, Cullis J, Novak T, et al. Brain structural signature of familial predisposition for bipolar disorder: replicable evidence for involvement of the right inferior frontal gyrus. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Drapier D, Surguladze S, Marshall N, et al. Genetic liability for bipolar disorder is characterized by excess frontal activation in response to a working memory task. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]