Summary

Gram-negative bacteria have evolved modification machinery to promote a dynamic outer membrane in response to a continually fluctuating environment. The kinase LpxT, for example, adds a phosphate group to the lipid A moiety of some Gram-negatives including Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. LpxT activity is inhibited under conditions that compromise membrane integrity, resulting instead in the addition of positively charged groups to lipid A that increase membrane stability and provide resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. We have now identified a functional lpxT ortholog in P. aeruginosa. LpxTPa has unique enzymatic characteristics, as it is able to phosphorylate P. aeruginosa lipid A at two sites of the molecule. Surprisingly, a previously uncharacterized lipid A 4′-dephospho-1-triphosphate species was detected. LpxTPa activity is inhibited by magnesium independently of lpxTPa transcription. Modulation of LpxTPa activity is influenced by transcription of the lipid A aminoarabinose transferase ArnT, known to be activated in response to limiting magnesium. These results demonstrate a divergent activity of LpxTPa, and suggest the existence of a coordinated regulatory mechanism that permits adaptation to a changing environment.

Keywords: lipid A, LpxT, Pseudomonas, outer membrane, lipopolysaccharide, LPS, kinase

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium commonly found in soil and aquatic environments, is also a versatile opportunistic pathogen that can cause both acute and chronic infections (Lyczak et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006). Acute nosocomial infections of P. aeruginosa are a common problem in immunocompromised individuals, including patients undergoing chemotherapy or burn wound treatment (Rumbaugh et al., 1999; Moskowitz and Ernst, 2010). Patients with diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF), however, can develop chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections that persist for months or even years (Moskowitz and Ernst, 2010). The adaptability of this organism makes it an extremely persistent pathogen, and infections caused by P. aeruginosa can be debilitating and potentially fatal (Lyczak et al., 2000).

The outer membrane is the first line of bacterial defense against environmental stressors, such as antimicrobial peptides. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which constitutes the outer leaflet of the outer membrane, is thus a critical molecule that can act as a protective barrier from such deleterious conditions. This glycolipid is composed of three domains: a lipid A anchor, a core oligosaccharide, and an O-antigen polysaccharide (Whitfield and Trent, 2014). The lipid A moiety of Gram-negative bacteria is of particular importance as it is the endotoxic portion of the molecule (Whitfield and Trent, 2014). Lipid A is synthesized via a highly conserved pathway requiring nine enzymes, resulting in a similar hexa-acylated, bis-phosphorylated molecule across various species (Fig. 1A) (Whitfield and Trent, 2014).

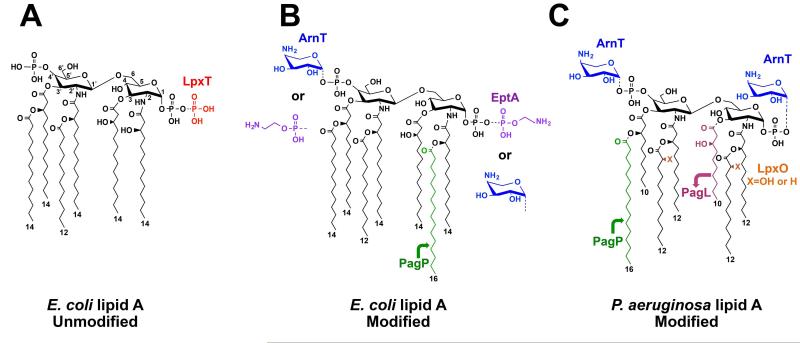

Fig. 1.

Comparison of lipid A structures of E. coli and P. aeruginosa, with and without modifications. A) Canonical hexa-ayclated, bis-phosphorylated lipid A structure of E. coli is shown in black. Phosphorylation of the lipid A 1-phosphate group by LpxT, which occurs for approximately one-third of lipid A species in standard growth media, is indicated in red. B) Canonical lipid A structure of E. coli is shown in black while possible modifications are indicated in color including pEtN addition by EptA (purple), L-4AraN addition by ArnT (blue), and addition of a palmitate (C16:0) chain by PagP (green). C) Hexa-acylated, bis-phosphorylated lipid A structure of P. aeruginosa is shown in black. Modifications are indicated including L-Ara4N addition (blue), palmitate chain addition (green), removal of the 3-hydroxydecanoate acyl chain by PagL (pink), and hydroxylation of the C12 secondary acyl chains by LpxO (orange).

Although a canonical lipid A molecule is initially produced in nearly all Gram-negatives, elaborate lipid A modification systems exist that are responsible for the diversity of lipid A molecules produced by different bacterial species (Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014). Alterations to the lipid A acyl chains can affect the toxicity of lipid A, as well as bacterial resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. Such alterations can include addition of a palmitate (C16:0) acyl chain via the enzyme PagP in E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1B & C) (Guo et al., 1998; Bishop et al., 2000; Thaipisuttikul et al., 2014), while the enzyme PagL in P. aeruginosa removes the C10 acyl chain at the 3 position (Fig. 1C) (Trent et al., 2001a; Ernst, 1999; Ernst et al., 2006). Additionally, LpxO can hydroxylate both secondary C12 chains of Pseudomonas lipid A (Fig. 1C). While E. coli does not contain an LpxO ortholog, this enzyme is found in S. enterica (Gibbons et al., 2008).

The phosphate groups of lipid A can also be modified with several different moieties, which can affect membrane stability. In E. coli, the kinase LpxT transfers a phosphate group from undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (Und-PP) strictly to the 1-phosphate group of lipid A (Touzé et al., 2007). This results in regeneration of undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P), an important precursor involved in the biosynthesis of bacterial membrane components, while simultaneously forming tris-phosphorylated (1-diphosphate) lipid A (Touzé et al., 2007). Positively charged moieties can be added to mask the anionic phosphate groups of lipid A, thereby increasing resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. For example, the enzyme ArnT transfers the cationic sugar 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (L-Ara4N) to the 1- and 4′-phosphate groups of E. coli and P. aeruginosa lipid A (Fig. 1B & C) (Bhat et al., 1990; Ernst, 1999; Trent et al., 2001b). Another positively charged group, phosphoethanolamine (pEtN), is added primarily to the lipid A 1-phosphate group of E. coli by the enzyme EptA (Fig. 1B) (Zhou et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2004) The core of E. coli LPS can also be decorated with pEtN via the enzyme EptB; this modification has been shown to play a role in cationic peptide resistance (Reynolds et al., 2005; Moon and Gottesman, 2009).

Structural modification of lipid A is a common adaptive response to environmental flux, and is often the downstream result of two-component system activation by specific external stimuli (Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014). For example, transcription of arnT in P. aeruginosa is primarily induced by the two-component systems PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB, although recent studies have reported the involvement of additional systems (McPhee et al., 2006; Gutu et al., 2013). Both of these systems respond to limiting magnesium, while PmrA-PmrB can also sense subinhibitory concentrations of cationic antimicrobial peptides (McPhee et al., 2003; McPhee et al., 2006). In E. coli and S. enterica, EptA competes with LpxT for modification at the 1-phosphate group (Herrera et al., 2010). LpxT activity as a lipid A kinase is inhibited in response to conditions that induce eptA expression via the two-component system PmrA-PmrB, such as limiting magnesium or an excess of extracellular ferric iron (Guo et al., 1997; Wösten et al., 2000; Herrera et al., 2010). Activation of PmrA induces transcription of a small regulatory peptide, PmrR, which interacts with LpxT to inhibit its activity (Kato et al., 2012). This leaves the lipid A 1-phosphate group open to pEtN addition by EptA. In this way, the bacterial cell can precisely orchestrate and permit the most beneficial modifications in response to the surrounding environment (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012).

While LpxT has only been characterized in E. coli and S. enterica, tris-phosphorylated lipid A species have previously been reported in other Gram-negatives including Neisseria meningitidis and Yersinia pestis (Cox et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2008; John et al., 2009). Despite the implication that lpxT orthologs are widespread, there remains a lack of studies examining the biochemistry and regulation of these orthologs. Work in E. coli and S. enterica has revealed the importance of lpxT regulation to promote the addition of positively charged moieties to lipid A; whether such coordinated regulation exists in other Gram-negatives is currently unknown (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012). We therefore set out to determine the existence of an LpxT ortholog in P. aeruginosa and, if present, how this enzyme is regulated.

Here we report the identification and characterization of a functional LpxT ortholog in P. aeruginosa. We show that LpxTPa activity is distinct from that of LpxTEc in that it can add not only to the 1-phosphate, but the 4′-position as well. We also describe the first reported example of a minor lipid A 1-triphosphate species. Further, we demonstrate that while phosphate group addition to P. aeruginosa lipid A readily occurs when magnesium concentration is high, LpxTPa activity is inhibited when magnesium is limiting, and instead L-Ara4N modification occurs via the enzyme ArnT. Deletion of arnT, however, results in partial restoration of LpxTPa activity, suggesting coordinated regulation of modification at the lipid A phosphate groups. Further investigation of LpxTPa and how it is regulated will allow better understanding of lipid A modification machinery in this important opportunistic pathogen.

Results

P. aeruginosa lipid A is modified with an additional phosphate

Reports of tris-phosphorylated lipid A in several different organisms suggest that lpxT-mediated phosphorylation of lipid A is widespread across Gram-negatives (Cox et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2008; John et al., 2009). We began our search for an lpxT ortholog in P. aeruginosa by performing a BLAST (NCBI) bioinformatics analysis to identify highly similar proteins to K-12 E. coli lpxT (lpxTEc). A single candidate with significant similarity, PA14_68620 was identified, having 30% sequence identity and an e-value of 1e10-18. This gene is conserved among members of the Pseudomonas genus, according to the Pseudomonas Genome Database (Winsor et al., 2011).

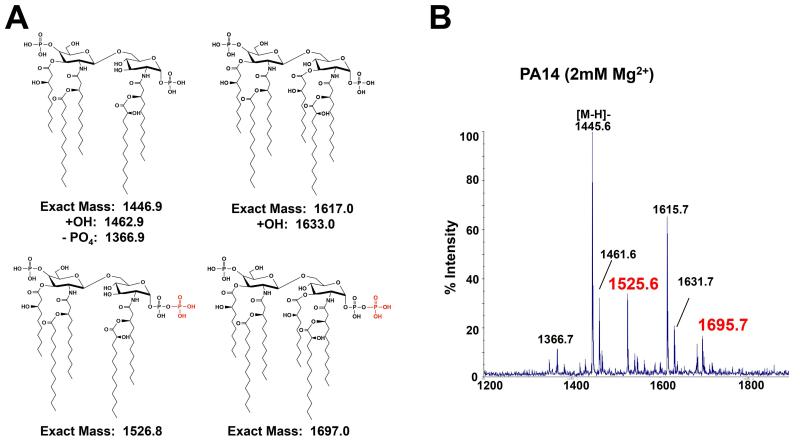

The existence of this ortholog (herein referred to as lpxTPa) prompted us to determine whether P. aeruginosa lipid A is modified with an additional phosphate group. Lipid A was isolated from P. aeruginosa grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2mM MgSO4 and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS). A MgSO4 concentration of 2mM was used, as this concentration of divalent cations has been reported to occur in the human body (Fernandez et al., 2010). Lipid A tris-phosphate was clearly detected for both the predominant, penta-acylated species and the less-abundant hexa-acylated species, generating major molecular ions at m/z 1525.6 and 1695.7, respectively (predicted [M-H]− at m/z 1525.8 and 1696.0) (Fig. 2A & B). This result confirms that P. aeruginosa lipid A can be tris-phosphorylated.

Fig. 2.

P. aeruginosa lipid A is modified with an additional phosphate group. A) Structures of the predominant penta- and hexa-acylated lipid A species and their exact masses are shown, with the corresponding phosphate-modified species shown below. Phosphate group addition is highlighted in red. B) MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the 480mM ammonium acetate lipid A eluate isolated from P. aeruginosa grown in 1 L MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4 shows penta- and hexa-acylated lipid A species (m/z at 1445.6 and 1615.7, respectively) as well as penta- and hexa-acylated lipid A tris-phosphate (m/z at 1525.6 and 1695.7, respectively; red).

Identification of a functional lpxT ortholog in P. aeruginosa

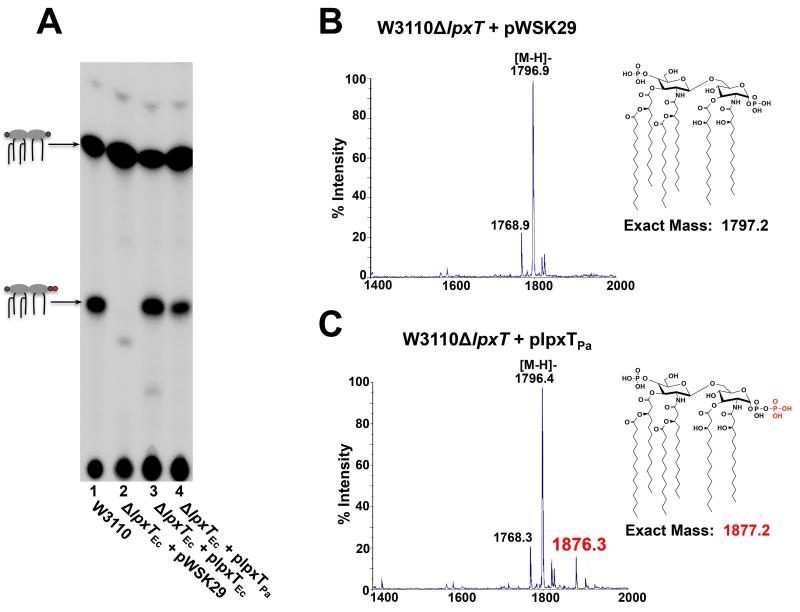

Given that P. aeruginosa lipid A can be modified with an additional phosphate group, the next goal was to determine whether lpxTPa (PA14_68620) is the enzyme responsible for this modification. lpxTPa was expressed in trans in an E. coli lpxT mutant (W3110δlpxTEc), and 32Pi-labelled lipid A from this strain was isolated and separated by TLC. The migration of E. coli lipid A in our TLC solvent system has been well-characterized, and consists of two major species: approximately two-thirds bis-phosphorylated lipid A, and one-third tris-phosphorylated lipid A (lipid A 1-diphosphate) due to LpxTEc activity (Fig. 3A, lane 1) (Herrera et al., 2010). Deletion of lpxTEc results in a single, bis-phosphorylated lipid A species (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Both lpxTEc and lpxTPa were able to complement the lpxTEc mutant, as shown by the restoration of the lipid A tris-phosphate species (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4). LpxTPa activity was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, in which lpxTPa-dependent phosphorylation of lipid A corresponds to the peak at m/z 1876.3 (predicted [M-H]− at m/z 1876.2) (Fig. 3B &C).

Fig. 3.

Heterologous expression of the P. aeruginosa lpxT ortholog restores tris-phosphorylated lipid A species in an E. coli W3110δlpxT mutant. A) Cells were grown in LB medium. Major 32P-labelled lipid A species are indicated with a cartoon of the corresponding structure; colors of groups added to the lipid A molecule correspond to colors used in Fig. 1. Wild-type E. coli W3110 lipid A is isolated as two major species, two-thirds bis-phosphorylated lipid A with phosphates at the 1 and 4′ positions, and one-third tris-phosphorylated lipid A, or lipid A 1-diphosphate (Lane 1). TLC separation of lipid A shows that lpxTPa, like lpxTEc, can modifiy E. coli lipid A with a phosphate group (lanes 3 and 4). B & C) MALDI-TOF analysis of lipid A isolated from W3110δlpxT + empty vector (pWSK29) (B) and W3110δlpxT + plpxTPa (C) demonstrates that lpxTPa can modify E. coli lipid A with an additional phosphate group (m/z at 1876.3, red).

An lpxTPa deletion mutant cannot phosphorylate lipid A

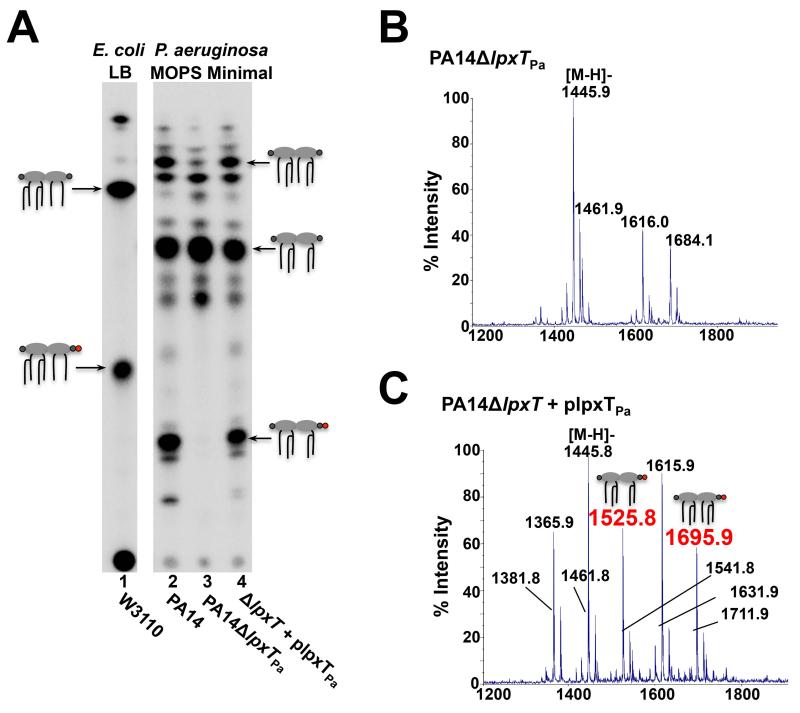

The necessity of lpxTPa for phosphate modification of P. aeruginosa lipid A was next examined by generating a chromosomal deletion mutant of lpxTPa. Lipid A from 32Pi-labelled wild-type, PA14 δ lpxTPa, and complemented mutant strains was isolated from cells grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4 and separated by TLC. Deletion of lpxTPa resulted in loss of a major lipid A species predicted to be tris-phosphorylated lipid A (Fig. 4A, lane 3) that was restored upon complementation with lpxTPa (Fig. 4A, lane 4). Samples isolated from P. aeruginosa grown in rich medium (LB) also showed LpxTPa-dependent phosphorylation of lipid A (Fig. S1). The lack of a lipid A tris-phosphate species in the lpxTPa deletion mutant was confirmed by MALDI-TOF and ESI-MS (Figs. 4B and S2). In the MALDI-TOF spectrum of the complemented mutant strain, however, additional peaks corresponding to tris-phosphorylated lipid A species were easily detected (Fig. 4C). lpxTPa is thus required for phosphate modification of P. aerguinosa lipid A.

Fig. 4.

lpxTPa is necessary for phosphorylation of P. aeruginosa lipid A. A) E. coli was grown in LB, P. aeruginosa was grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4. Minor lipid A species below major P. aeruginosa species correspond to hydroxylated forms of lipid A due to LpxO activity. TLC separation of lipid A shows absence of tris-phosphorylated lipid A when lpxTPa is deleted (lane 3). Upon complementation with plpxTPa, lipid A tris-phosphate is restored (lane 4). B) MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the 480mM ammonium acetate lipid A eluate isolated from PA14δlpxTPa grown in 1 L MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4 shows no peaks corresponding to tris-phosphorylated lipid A. C) MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the 480mM elution fraction of lipid A reveals that when lpxTPa is expressed in trans in the PA14δlpxTPa mutant, phosphorylation of both penta- and hexa-acylated lipid A is restored (m/z at 1525.8 and 1695.8, respectively; red).

P. aeruginosa and E. coli LpxT have divergent activity

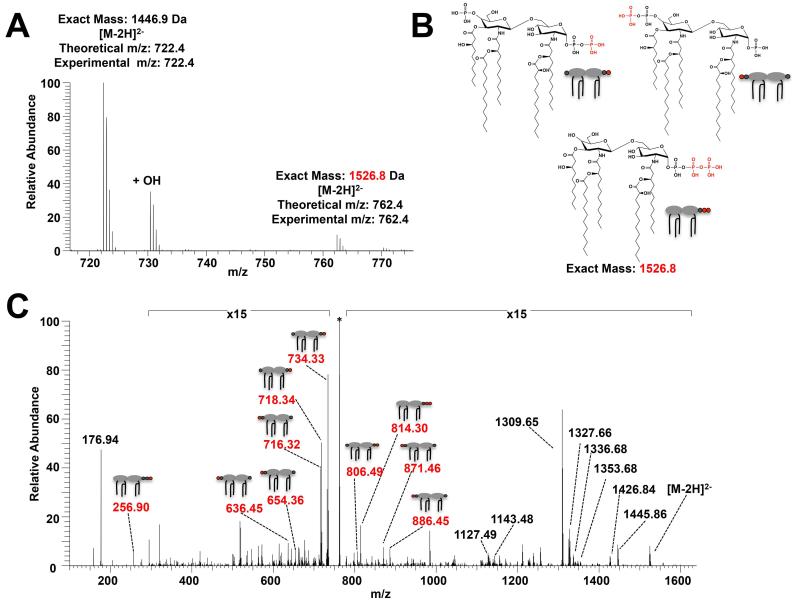

Previous analysis of tris-phosphorylated E. coli lipid A has detected phosphate group addition exclusively at the 1-position (Zhou et al., 1999; Touzé et al., 2007). The next approach was to determine whether LpxTPa has a similar site-specificity to that of LpxTEc. Lipid A was isolated from P. aeruginosa grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2mM MgSO4 and analyzed first by ESI-MS (Fig. 5A) and subsequently by ultraviolet photodissociation mass spectrometry (UVPD-MS) (Fig. 5C), resulting in ions from multiple cleavages of the lipid A parent molecules (selected precursor m/z 762.4). UVPD-MS analysis showed that unlike in E. coli, phosphate modification of P. aeruginosa lipid A can occur both at the 1-phosphate and the 4′-phosphate groups (Figs. 5B and S3A & B). Cleavages generating molecular ions at m/z 718.34, 734.33, and 806.49 allowed identification of the 1-diphosphate species, while ions at m/z 636.45, 654.36, 871.46, and 886.45 provided strong evidence for a 4′-diphosphate species (Figs. 5C and S3A & B). Interestingly, a low abundance of lipid A 1-triphosphate was also identified (Figs. 5B and S3C). UVPD-MS resulted in fragment ions at m/z 256.90 and 814.30 thus confirming the identity of the 1-triphosphate species (Figs. 5C and S3C). This unique species is especially surprising given that in addition to the 1-position being modified with two additional phosphate groups, the 4′ phosphate of the glucosamine backbone is absent. This not only demonstrates a previously uncharacterized activity of LpxT, but also suggests the existence of a lipid A phosphatase in P. aeruginosa, as such an enzyme is necessary to cleave the lipid A 4′ phosphate (Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014).

Fig. 5.

LpxTPa-dependent phosphorylation of P. aeruginosa lipid A results in multiple tris-phosphorylated species. A) Negative ion mode ESI mass spectrum of PA14 P. aeruginosa revealing a mixture of [M-2H]2− lipid A corresponding to wild type penta-acylated lipid A [Exact mass = 1446.9 Da] and a species corresponding to an addition of one phosphate group [Exact Mass = 1526.8 Da]. B) A mixture of three distinct lipid A species (1-pyrophosphate, 4~-pyrophosphate, and 1-triphosphate species) were identified through the C) UVPD mass spectrum of the [M-2H]2− m/z 762.4 from (A). Key fragment ions corresponding to each of the different lipid A types are highlighted in red with the corresponding precursor structure assignment while the remaining fragment ions revealed the lipid A acylation pattern. Fragmentation cleavage maps for the identified species are shown in Fig. S3 and the precursor ion is marked with an asterisk.

LpxTPa activity is modulated by magnesium

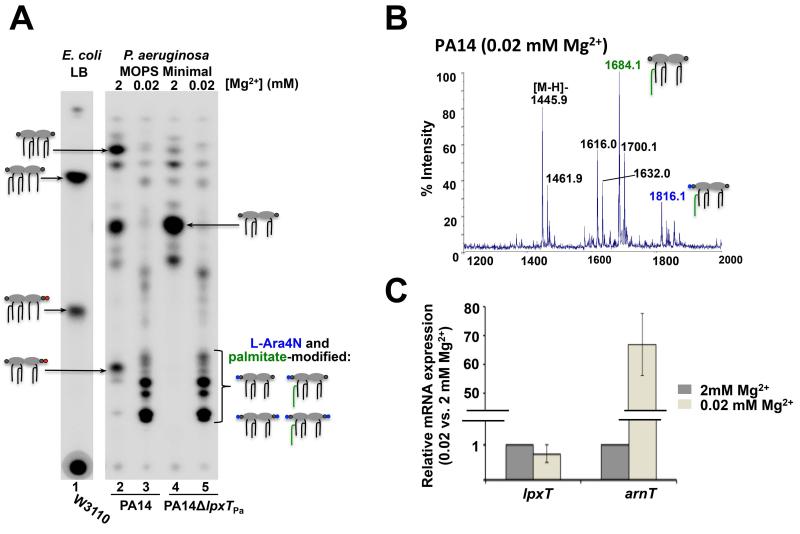

Lipid A modification with positively charged L-Ara4N and pEtN groups by the enzymes ArnT and EptA, respectively, improves bacterial survival in deleterious conditions such as limiting magnesium and exposure to cationic antimicrobial peptides (Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014). Modulation of LpxT activity permits pEtN modification at the 1-phosphate group by EptA, without competition from LpxT (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012). The P. aeruginosa L-Ara4N transferase can modify both phosphate groups of lipid A (Ernst, 1999) and according to our findings the same can be said for LpxTPa. Therefore, we speculated that LpxTPa activity might be inhibited under conditions that induce arnT transcription to prevent competition between phosphate group and L-Ara4N addition. To test this possibility, lipid A was isolated from 32Pi-labelled P. aeruginosa cells grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with either 2 or 0.02 mM MgSO4 (high or low Mg2+), the latter of which has been previously shown to induce arnT transcription via PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB (McPhee et al., 2003; McPhee et al., 2006). Growth in low Mg2+ resulted in absence of the tris-phosphorylated lipid A species and the appearance of L-Ara4N and palmitate-modified lipid A species due to ArnT and PagP activity, respectively (Fig. 6A, lane 3). Absence of tris-phosphorylated lipid A was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 6B). Double L-Ara4N-modified species were also detected in our MS analysis of the wash fraction of this lipid A sample (Fig. S4). These results suggest that limiting Mg2+during growth results in inhibition of LpxTPa activity, either by influencing lpxTPa transcription or enzyme activity.

Fig. 6.

LpxTPa activity is modulated by magnesium. A) E. coli was grown in LB, P. aeruginosa was grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 or 0.02 mM MgSO4, as indicated. When grown in low magnesium, lipid A tris-phosphate was not detected by TLC separation (lane 3). Instead, L-Ara4N and palmitate-modified species were observed for both PA14 and PA14δlpxT grown in low magnesium (lanes 3 and 5). Colors of lipid A modifications in cartoons correspond to colors used in Fig. 1. B) MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the 480mM ammonium acetate lipid A eluate shows the absence of tris-phosphorylated species in PA14 grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 0.02 mM MgSO4. Palmitoylation of the penta-acylated species (m/z at 1684.1) is indicated in green. C) Relative gene expression of lpxTPa and arnT when grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 0.02 mM MgSO4 compared to 2 mM MgSO4 shows that while lpxTPa transcription does not significantly change (<1.5-fold difference) with respect to magnesium concentration, arnT transcription significantly increases in 0.02 mM MgSO4.

It was then investigated whether Mg2+-dependent modulation of LpxTPa occurs at the transcriptional level. Quantitative PCR was performed to compare the level of lpxTPa expression in high or low Mg2+, using the housekeeping gene clpX as an internal control (Palmer et al., 2005). The transcription of arnT was also analyzed under the same conditions as a positive control for Mg2+ regulation. While arnT transcription is strongly induced when Mg2+ is limiting, the transcription of lpxTPa does not significantly change (<1.5-fold difference) (Fig. 6C). Mg2+-dependent modulation of LpxTPa activity is thus independent of lpxTPa transcription, as is the case in E. coli and S. enterica (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012).

LpxTPa activity in low magnesium is partially restored in the PA14δarnT mutant

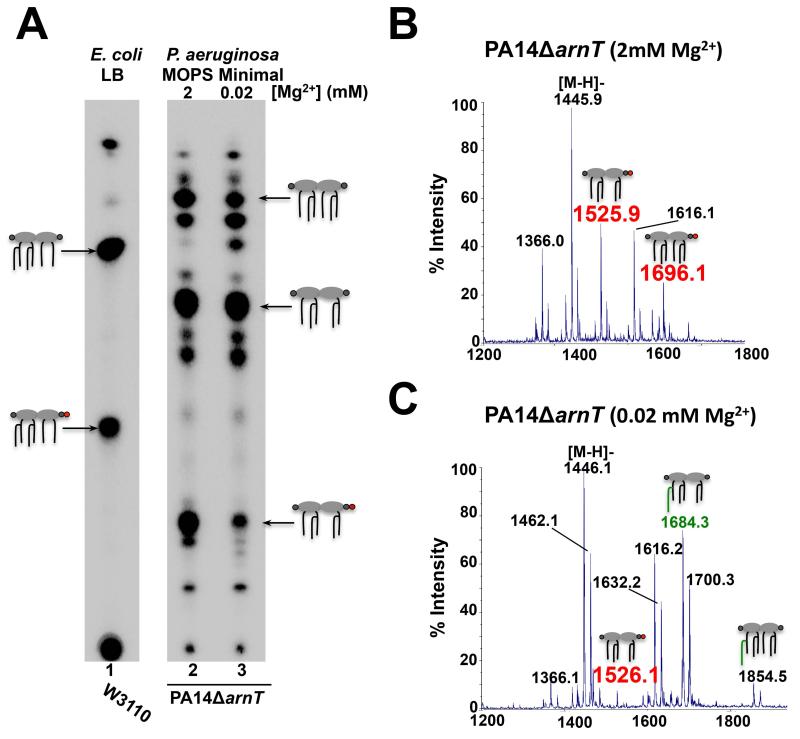

In E. coli and S. enterica, although LpxT-dependent lipid A phosphorylation at the 1-phosphate group occurs under normal laboratory growth conditions, its activity is inhibited when eptA transcription is activated by environmental stimuli (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012). If lpxT is deleted, however, a small amount of pEtN-modified lipid A is detected even under conditions that do not normally induce eptA transcription (Herrera et al., 2010). Given that ArnT can add L-Ara4N to both phosphate groups of lipid A (Fig. S5) (Ernst, 1999), we questioned whether a similar mechanism occurs in P. aeruginosa to control phosphate group and L-Ara4N addition thereby reducing their competition. Since deletion of lpxTPa does not result in detectable L-Ara4N-modified lipid A when Mg2+ concentration is high (Fig. 4), we wondered if deletion of arnT would result in LpxTPa activity in low Mg2+. Accordingly, 32Pi-labelled lipid A was isolated from PA14δarnT grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with high or low Mg2+ and separated by TLC (Fig. 7). When arnT is absent from the genome, the lipid A tris-phosphate species was partially restored in cells grown in low Mg2+ (Fig. 7A, lane 3). Partial restoration of the tris-phosphorylated lipid A species in the PA14δarnT mutant grown in low Mg2+ was further confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 7C). Together, these results suggest that coordinated control of lipid A modification at the phosphate groups occurs in P. aeruginosa.

Fig. 7.

LpxTPa activity in low magnesium is partially restored in the PA14δarnT mutant. A) E. coli was grown in LB, P. aeruginosa was grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 or 0.02 mM MgSO4 as indicated. When arnT is deleted, a small amount of tris-phosphorylated lipid A is detected in lipid A isolated from cells grown in low magnesium (lane 3). B) When PA14δarnT is grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, tris-phosphorylated lipid A species are readily detected in the 480mM ammonium acetate lipid A eluate fraction (m/z at 1525.8 and 1695.9, respectively; red). C) Tris-phosphorylated lipid A species isolated from PA14δarnT grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 0.02 mM MgSO4 are detected as a minor species (m/z at 1526.1; red).

Discussion

Modulation of the bacterial outer membrane is crucial for bacterial survival in a changing and potentially deleterious environment. When outer membrane integrity remains uncompromised (for example, when Mg2+ is plentiful), phosphate modification of lipid A occurs readily through the action of LpxT (Touzé et al., 2007; Herrera et al., 2010). However, when Mg2+ becomes scarce or cationic antimicrobial peptides are present, modification of lipid A with L-Ara4N, pEtN, or palmitate increase bacterial fitness (McPhee et al., 2003; McPhee et al., 2006; Murata et al., 2007; Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014). Environmental stimuli are sensed by two-component regulatory systems that orchestrate outer membrane remodelling by controlling the expression or activity of various lipid A modification enzymes in a coordinated manner (Needham and Trent, 2013; Whitfield and Trent, 2014). For example, phosphorylation of lipid A must be inhibited, while simultaneously promoting the addition of cationic groups at the lipid A phosphates to increase membrane stability (Herrera et al., 2010; Kato et al., 2012).

Previous studies have shown the presence of free pyrophosphate groups in P. aeruginosa lipid A samples analyzed by mass spectrometry, implicating that lipid A from this organism can be tris-phosphorylated (Jones et al., 2008). We have now identified a P. aeruginosa LpxT ortholog that can function on both E. coli and P. aeruginosa lipid A (Figs. 3 and 4). As is the case in E. coli and S. enterica, phosphate group addition occurs under normal laboratory growth conditions in which Mg2+ concentration is replete (Figs. 2B and S1). In all three organisms, limiting Mg2+ concentration inhibits LpxT activity while promoting expression of enzymes that add positively charged groups to lipid A. Importantly, there are several critical differences in LpxTPa activity from that of E. coli or S. enterica, which are highlighted in Table 1. These differences include the dual positional specificity of LpxTPa for lipid A modification and competition with ArnT rather than EptA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of LpxT lipid A enzymatic characteristics

| Property of LpxT | Microorganism | |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli/S. enterica | P. aeruginosa | |

| Kinase activity at 1-phosphate group? |

Yes, adds one phosphate group |

Yes, adds one or two phosphate groups |

| Kinase activity at 4′-phosphate group? |

No | Yes, adds one phosphate group |

| Conditions known to inhibit activity |

Low [Mg2+], mildly acidic pH, excess [Fe3+] |

Low [Mg2+] |

| Mg2+-dependent inhibition: transcriptional or post- transcriptional? |

Post-transcriptional | Post-transcriptional |

| Regulatory system involved in LpxT inhibition |

PmrA-PmrB, via the small peptide PmrR |

Unknown, no PmrR ortholog present |

| Competition with other lipid A modification enzymes? |

Yes, competes with EptA for modification at 1- phosphate group |

Yes, competes with ArnT for modification at both phosphate groups |

| Other factors related to activity or expression |

Basal EptA activity when IpxT is deleted |

LpxTPa active in low [Mg2+] when arnT is deleted |

Previous work in E. coli has demonstrated that LpxT is a member of the undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate (Und-PP) phosphatase family of enzymes, which remove a phosphate group from the carrier lipid Und-PP (Touzé et al., 2007). Und-P is a vital molecule required for shuttling polysaccharide intermediates involved in the synthesis of important polymers such as peptidoglycan and O-antigen across the inner membrane (Tatar et al., 2007; Touzé et al., 2007). By removing a phosphate group from Und-PP, LpxT regenerates Und-P and thus plays a role in the cycle of bacterial cell envelope synthesis (Tatar et al., 2007), while also modifying the lipid A anchor of LPS (Touzé et al., 2007). In E. coli, three additional Und-PP phosphatases (YbjG, PgpB, and UppP) are also present that can regenerate Und-P (El Ghachi et al., 2005; Tatar et al., 2007). UppP (formerly named BacA) is responsible for the majority of Und-PP dephosphorylation, while the other three account for the remaining activity (Tatar et al., 2007). Like LpxT, PgpB has activity on substrates other than Und-PP; it is one of three enzymes in E. coli that functions as a phosphatidylglycerophosphate phosphatase (Icho and Raetz, 1983; El Ghachi et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2011). These enzymes dephosphorylate phosphatidylglycerolphosphate, a necessary intermediate in the synthesis of the phospholipid phosphatidylglycerol (Icho and Raetz, 1983). Although they have not yet been characterized, homologs of the other Und-PP phosphatases exist in P. aeruginosa as well.

Characterization of LpxTPa positional specificity revealed that this enzyme has unique activity in that it can phosphorylate both the 1- and the 4′ phosphate groups of lipid A (Figs. 5 and S4), while LpxT of E. coli modifies strictly the 1-position with a single phosphate group (Zhou et al., 1999). We have also demonstrated that deletion of lpxTPa results in loss of any lipid A tris-phosphate species, suggesting that LpxTPa is both necessary and responsible for phosphorylation of both positions of lipid A (Figs. 4A and B; S2). Quite surprisingly, we observed that LpxTPa adds not only one phosphate group to the 1- or 4′-position of lipid A, but in some cases it can add two phosphate groups at the 1-position, resulting in a minor lipid A 1-triphosphate species (Figs. 5 and S3). This novel species has never been reported in any microorganism. While it is unknown whether a specific regulatory condition exists that might promote such activity of LpxTPa, under the growth conditions used, this 1-triphosphate lipid A species is in very low abundance compared to 1- or 4′-diphosphate lipid A species.

Another unexpected feature of the 1-triphosphate species is its lack of a 4′ phosphate group linked to the glucosamine backbone. While it is common for the lipid A 1-phosphate group to cleave from the molecule during either the mild acid hydrolysis step of lipid A purification or in the mass spectrometer, the 4′ phosphate group is not susceptible to such cleavage (Ernst et al., 2006). 4′-dephosphorylated lipid A species are found in other organisms, such as Helicobacter pylori and Francisella tularensis, due to the activity of lipid A 4′ phosphatases (Wang et al., 2006; Cullen et al., 2011). Although a P. aeruginosa lipid A 4′-phosphatase has not been identified, P. aeruginosa has phosphatidylglycerolphosphate phosphatase orthologs. As these phosphatases can remove a phosphate group from phosphatidylglycerolphosphosphate and leave behind a free hydroxyl group, it is possible that one of these proteins is responsible for removal of the 4′ phosphate group (Icho and Raetz, 1983). We also cannot rule out the possibility that LpxTPa itself is acting as a lipid A 4′ phosphatase. The existence of this unusual lipid A species further demonstrates the need for a deeper understanding of lipid A modification systems in P. aeruginosa.

We have also found that LpxTPa activity is inhibited by growth in limiting Mg2+ independently of lpxTPa transcription. While TLC and MALDI-TOF analysis of lipid A from bacteria grown in low Mg2+ demonstrated no phosphate group addition to lipid A (Fig. 6A and B), our quantitative PCR data revealed no significant change in lpxTPa transcription in response to limiting Mg2+ (Fig. 6C). Instead, low Mg2+ induces transcription of arnT and pagP resulting in addition of L-Ara4N and palmitate, respectively (Fig. 6C and S5) (McPhee et al., 2006; Thaipisuttikul et al., 2014). However, if arnT is deleted from the genome, LpxTPa remains partially active even when Mg2+ is limiting (Fig. 7). While tris-phosphorylated lipid A species are present in the PA14δarnT mutant, this species is clearly diminished when cells are grown in low Mg2+ compared to growth in high Mg2+ (Fig. 7A and B). This strongly suggests that the absence of tris-phosphorylated species in limiting Mg2+ is not merely due to competition from ArnT. Instead, Mg2+-dependent reduction of LpxTPa activity occurs independently from ArnT activity. By altering the expression or activity of these two modification enzymes, P. aeruginosa has evolved a coordinated mechanism that mediates appropriate alterations in the outer membrane to promote survival in a changing environment.

This report demonstrates another level of control involved in environmental adaptation that can contribute to P. aeruginosa’s ability to persist as a pathogen. While LpxTPa-dependent lipid A phosphorylation has not yet been definitively linked to an increase in cell survival under a specific environmental condition, a new study has revealed that in a P. aeruginosa burned mouse acute infection model, an lpxTPa mutant was significantly less fit within the burn wound relative to analysis in succinate growth medium (Turner et al., 2014). Further investigation is necessary to determine the role of lpxTPa in acute P. aeruginosa infections.

Although we have begun to characterize LpxTPa regulation, future work is required to determine which regulatory system or systems might be involved in Mg2+-dependent modulation of LpxTPa activity. Furthermore, we have not tested whether any other lipid A modification activation signals (i.e. cationic antimicrobial peptides) inhibit LpxTPa activity as well. In P. aeruginosa both PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB are independently activated by limiting magnesium, while the latter system can also be activated by antimicrobial peptides such as polymyxin (McPhee et al., 2003; McPhee et al., 2006). In E. coli and S. enterica, inhibition of LpxT activity is PmrA-dependent. Upon activation by inducing environmental conditions, PmrA acts as a transcription factor to regulate many target genes. One such gene encodes the small regulatory protein PmrR, which interacts with LpxT to prevent its function (Kato et al., 2012). While PmrR orthologs exist in other enteric bacteria, including Citrobacter koseri and Klebsiella pneumonia, no such ortholog is present in microorganisms such as P. aeruginosa and N. meningitidis (Kato et al., 2012). It is therefore likely that a distinct regulatory mechanism from E. coli and S. enterica is involved in LpxT regulation in other Gram-negatives like P. aeruginosa. Further investigation of regulatory mechanisms involved in modulation of LpxTPa activity and of P. aeruginosa lipid A remodelling in general is needed to better understand how this formidable pathogen adapts to its surroundings.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. E. coli strains were grown in LB broth or agar (Difco) at 37 ° C. P. aeruginosa strains were grown on LB agar plates, and overnight cultures were routinely grown in LB broth at 37 ° C. Overnight P. aeruginosa cultures were diluted to an OD600 of ~0.05 in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-buffered minimal medium (50mM MOPS, 93mM NH4Cl, 43mM NaCl, 2mM KH2PO4) supplemented with 3.5 μ M FeSO4 • 7H2O, 20mM sodium succinate, and 2mM or 0.02mM MgSO4 as indicated. Ampicillin or carbenicillin were used at a concentration of 100μg/mL or 300μg/mL for E. coli or P. aeruginosa, respectively.

DNA and RNA preparation

Before preparing genomic DNA from an overnight culture, cells were washed two times with 0.1M NaCl. Genomic DNA was prepared from the Easy-DNA Kit (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted from cells grown in MOPS minimal medium with supplements at an OD600 of ~0.6 using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was treated with DNase from the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen) to eliminate residual DNA contamination. cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Recombinant DNA methods

Plasmid DNA was purified using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Prior to transformation into the target strain, plasmids were first transformed into E. coli strain XL1 Blue. DNA for recombinant techniques was amplified using either the DNA polymerase PfuTurboR (Stratagene) or Takara Ex Taq (Takara). PCR products were purified from agarose gels using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). All primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Table S2). Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and Antarctic Phosphatase used in this study for construction of plasmid vectors were purchased from New England Biolabs.

Construction of chromosomal gene deletion mutants

In-frame, markerless gene deletions in P. aeruginosa were generated by homologous recombination using the suicide plasmid pEX18Gm (Hoang et al., 1998). DNA fragments approximately 1Kb upstream and downstream of the target gene were individually amplified using primers listed in Table S2. The upstream flanking regions for lpxT and arnT deletion were amplified using primer pairs lpxTdel-outF, lpxTdel-inR and arnTdel-outF, arnTdel-inR, respectively. The downstream flanking regions were amplified using primers lpxTdel-inF, lpxTdel-outR for lpxT deletion, and arnTdel-inF, arnTdel-outR for arnT deletion. An assembly PCR was then carried out using the outF and outR primers corresponding to each gene (Table S2). Assembly PCR fragments were digested with restriction endonucleases EcoRI and HindIII, and ligated into pEX18Gm. This vector has a gentamycin resistance cassette to select for single recombinants, as well as a sacB gene conferring sensitivity to growth on sucrose to select for double crossover recombinants. The suicide vectors, pEX18-lpxTdel or pEX18-arnTdel were introduced into P. aeruginosa via conjugation with E. coli strain SM10 (de Lorenzo and Timmis, 1994). Deletion mutants were then screened for as described previously (Hoang et al., 1998). Mutations were confirmed by PCR.

Plasmid constructs

Complementation of W3110δlpxT was achieved by expressing either lpxTEc or lpxTPa in the low-copy number plasmid pWSK29 (Wang and Kushner, 1991), and PA14δlpxT was complemented by expressing lpxTPa in the medium-copy number plasmid pEX1.8 (Pearson et al., 1997). For generation of both constructs, the lpxTPa gene and RBS were amplified using primers PAlpxTF and PAlpxTR (Table S2), digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and ligated into vector cut with the same restriction endonucleases to yield plpxTPa and pEXlpxTPa. Constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Isolation and analysis of labelled lipid A

Cultures from overnight growth were diluted to an OD600 of ~0.05 in 5mL of fresh medium (as indicated) and labeled with 2.5 μ Ci/mL 32Pi (Perkin-Elmer). Cells were harvested at an OD600 of 0.8-1.0, and lipid A was isolated by mild acid hydrolysis as previously described (Zhou et al., 1999; Tran et al., 2004). 32Pi-labelled lipid A species were spotted on a TLC plate at ~5,000 cpm per lane (10,000 cpm for E. coli), and analyzed in a solvent system consisting of 50:50:16:5 (v/v) of chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, and water, respectively. TLC plates were dried, exposed to a phosphor screen overnight and imaged using a phosphor-imager (BioRad PMI).

Large scale lipid A isolation and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

Large scale 1L cultures were grown at 37 ° C to an OD600 of ~1.0 in MOPS minimal medium with the indicated concentration of MgSO4. Lipid A was prepared by mild acid hydrolysis, washed and dissolved in chloroform/methanol/water (2:3:1, v/v), as described (Hankins et al., 2013). Samples were then applied to a DEAE cellulose column, washed with chloroform/methanol/water (2:3:1, v/v), and eluted as separate fractions using chloroform/methanol/increasing concentrations of aqueous ammonium acetate (60mM, 120mM, 240mM, 480mM) (2:3:1, v/v), as described previously (Odegaard et al., 1997; Hankins et al., 2013). Typically, hydrophilic or monophosphorylated species fractionate at lower sodium acetate concentrations (flow-through, wash, 60 or 120mM elution fractions), while more hydrophobic, unmodified or phosphate-modified species fractionate at the highest concentration, 480mM sodium acetate. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was performed as previously described using a MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (ABI 4700 Proteomics Analyser) (Hankins et al., 2013).

ESI and UVPD mass spectrometry

Lipid A was isolated and prepared using the same techniques described for MALDI-TOF analysis. All MS experiments were executed on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Bremen, Germany) equipped with a 193-nm Coherent ExciStar XS excimer laser (Santa Clara, CA). The set-up used was similar to that previously described (Shaw et al., 2013; O’Brien et al., 2014b). Lipid A samples for mass analysis were directly infused using an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and analyzed as described previously (O’Brien et al., 2014a).

Quantitative PCR methods

Primers for quantitative PCR (qPCR) were designed using the Primer-BLAST tool (NCBI) and are listed in Table S2. qPCR was performed in a OneStep thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After determining primer efficiency, qPCR was performed on three biological replicates prepared in duplicate technical replicates of cDNA diluted 1:10 for each sample condition. The relative expression ratio of target gene to reference gene (clpX) (normalized to 1) was calculated as described (Pfaffl, 2001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding from NIH (grants AI064184 & AI76322 to M.S.T. & GM103655 to J.S.B.), the Welch Foundation (F-1155 to J.S.B.), the Army Research Office (grant W911NF-12-1-0390 to M.S.T.) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (grant Trent13G0 to M.S.T.) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Bhat R, Marx A, Galanos C, Conrad RS. Structural studies of lipid A from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: occurrence of 4-amino-4-deoxyarabinose. Journal of bacteriology. 1990;172:6631–6636. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6631-6636.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop RE, Gibbons HS, Guina T, Trent MS, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. Transfer of palmitate from phospholipids to lipid A in outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 2000;19:5071–5080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdd507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox AD, Wright JC, Li J, Hood DW, Moxon ER, Richards JC. Phosphorylation of the lipid A region of meningococcal lipopolysaccharide: identification of a family of transferases that add phosphoethanolamine to lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3270–3277. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3270-3277.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen TW, Giles DK, Wolf LN, Ecobichon C, Boneca IG, Trent MS. Helicobacter pylori versus the Host: Remodeling of the Bacterial Outer Membrane Is Required for Survival in the Gastric Mucosa. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002454. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghachi M, Derbise A, Bouhss A, Mengin-Lecreulx D. Identification of multiple genes encoding membrane proteins with undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase (UppP) activity in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18689–18695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK. Specific Lipopolysaccharide Found in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. 1999;286:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK, Adams KN, Moskowitz SM, Kraig GM, Kawasaki K, Stead CM, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lipid A Deacylase: Selection for Expression and Loss within the Cystic Fibrosis Airway. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188:191–201. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.191-201.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez L, Gooderham WJ, Bains M, McPhee JB, Wiegand I, Hancock REW. Adaptive Resistance to the “Last Hope” Antibiotics Polymyxin B and Colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Is Mediated by the Novel Two-Component Regulatory System ParR-ParS. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54:3372–3382. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00242-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons HS, Reynolds CM, Guan Z, Raetz CRH. An Inner Membrane Dioxygenase that Generates the 2-Hydroxymyristate Moiety of Salmonella Lipid A. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2814–2825. doi: 10.1021/bi702457c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Lim KB, Gunn JS, Bainbridge B, Darveau RP, Hackett M, Miller SI. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Lim KB, Poduje CM, Daniel M, Gunn JS, Hackett M, Miller SI. Lipid A Acylation and Bacterial Resistance against Vertebrate Antimicrobial Peptides. Cell. 1998;95:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutu AD, Sgambati N, Strasbourger P, Brannon MK, Jacobs MA, Haugen E, et al. Polymyxin Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phoQ Mutants Is Dependent on Additional Two-Component Regulatory Systems. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57:2204–2215. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02353-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins JV, Madsen JA, Needham BD, Brodbelt JS, Trent MS. The Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria: Lipid A Isolation and Characterization. In: Delcour AH, editor. Bacterial Cell Surfaces. Humana Press; [Accessed May 15, 2014]. 2013. pp. 239–258. http://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1007/978-1-62703-245-2_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera CM, Hankins JV, Trent MS. Activation of PmrA inhibits LpxT-dependent phosphorylation of lipid A promoting resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1444–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-locaed DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icho T, Raetz CR. Multiple genes for membrane-bound phosphatases in Escherichia coli and their action on phospholipid precursors. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:722–730. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.722-730.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John CM, Liu M, Jarvis GA. Natural Phosphoryl and Acyl Variants of Lipid A from Neisseria meningitidis Strain 89I Differentially Induce Tumor Necrosis Factor-in Human Monocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:21515–21525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JW, Shaffer SA, Ernst RK, Goodlett DR, Tureček F. Determination of pyrophosphorylated forms of lipid A in Gram-negative bacteria using a multivaried mass spectrometric approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:12742–12747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800445105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, Chen HD, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Reciprocal Control between a Bacterium’s Regulatory System and the Modification Status of Its Lipopolysaccharide. Molecular Cell. 2012;47:897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DG, Urbach JM, Wu G, Liberati NT, Feinbaum RL, Miyata S, et al. Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Hsu F-F, Turk J, Groisman EA. The PmrA-Regulated pmrC Gene Mediates Phosphoethanolamine Modification of Lipid A and Polymyxin Resistance in Salmonella enterica. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186:4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deLorenzo V, Timmis KN. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Meth Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y-H, Guan Z, Zhao J, Raetz CRH. Three phosphatidylglycerol-phosphate phosphatases in the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5506–5518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JB, Bains M, Winsor G, Lewenza S, Kwasnicka A, Brazas MD, et al. Contribution of the PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB Two-Component Regulatory Systems to Mg2+-Induced Gene Regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188:3995–4006. doi: 10.1128/JB.00053-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JB, Lewenza S, Hancock REW. Cationic antimicrobial peptides activate a two-component regulatory system, PmrA-PmrB, that regulates resistance to polymyxin B and cationic antimicrobial peptides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PmrA-PmrB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Molecular Microbiology. 2003;50:205–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon K, Gottesman S. A PhoQ/P-regulated small RNA regulates sensitivity of Escherichia coli to antimicrobial peptides. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:1314–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz SM, Ernst RK. The role of Pseudomonas lipopolysaccharide in cystic fibrosis airway infection. Subcell Biochem. 2010;53:241–253. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9078-2_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Tseng W, Guina T, Miller SI, Nikaido H. PhoPQ-mediated regulation produces a more robust permeability barrier in the outer membrane of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7213–7222. doi: 10.1128/JB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BD, Trent MS. Fortifying the barrier: the impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:467–481. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J, Needham B, Brown D, Trent MS, Brodbelt J. [Accessed July 14, 2014];Top-Down Strategies for the Structural Elucidation of Intact Gram-negative Bacterial Endotoxins. Chem Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1039/C4SC01034E. http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2014/sc/c4sc01034e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JP, Needham BD, Henderson JC, Nowicki EM, Trent MS, Brodbelt JS. 193 nm ultraviolet photodissociation mass spectrometry for the structural elucidation of lipid A compounds in complex mixtures. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2138–2145. doi: 10.1021/ac403796n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegaard TJ, Kaltashov IA, Cotter RJ, Steeghs L, van der Ley P, Khan S, et al. Shortened hydroxyacyl chains on lipid A of Escherichia coli cells expressing a foreign UDP-N-acetylglucosamine O-acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19688–19696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer KL, Mashburn LM, Singh PK, Whiteley M. Cystic Fibrosis Sputum Supports Growth and Cues Key Aspects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Physiology. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5267–5277. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5267-5277.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JP, Pesci EC, Iglewski BH. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5756–5767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CM, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. A phosphoethanolamine transferase specific for the outer 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid residue of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Identification of the eptB gene and Ca2+ hypersensitivity of an eptB deletion mutant. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21202–21211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaugh KP, Griswold JA, Iglewski BH, Hamood AN. Contribution of Quorum Sensing to the Virulence ofPseudomonas aeruginosa in Burn Wound Infections. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:5854–5862. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5854-5862.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JB, Li W, Holden DD, Zhang Y, Griep-Raming J, Fellers RT, et al. Complete protein characterization using top-down mass spectrometry and ultraviolet photodissociation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12646–12651. doi: 10.1021/ja4029654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar LD, Marolda CL, Polischuk AN, van Leeuwen D, Valvano MA. An Escherichia coli undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate phosphatase implicated in undecaprenyl phosphate recycling. Microbiology. 2007;153:2518–2529. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaipisuttikul I, Hittle LE, Chandra R, Zangari D, Dixon CL, Garrett TA, et al. A divergent Pseudomonas aeruginosa palmitoyltransferase essential for cystic fibrosis-specific lipid A. Mol Microbiol. 2014;91:158–174. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touzé T, Tran AX, Hankins JV, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Trent MS. Periplasmic phosphorylation of lipid A is linked to the synthesis of undecaprenyl phosphate: Periplasmic dephosphorylation of undecaprenyl-PP. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;67:264–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AX, Karbarz MJ, Wang X, Raetz CRH, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Trent MS. Periplasmic Cleavage and Modification of the 1-Phosphate Group of Helicobacter pylori Lipid A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:55780–55791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406480200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent MS, Pabich W, Raetz CR, Miller SI. A PhoP/PhoQ-induced Lipase (PagL) that catalyzes 3-O-deacylation of lipid A precursors in membranes of Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 2001a Mar 23;276:9083–9092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. An inner membrane enzyme in Salmonella and Escherichia coli that transfers 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to lipid A: induction on polymyxin-resistant mutants and role of a novel lipid-linked donor. J Biol Chem. 2001b Nov 16;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KH, Everett J, Trivedi U, Rumbaugh KP, Whiteley M. Requirements for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute burn and chronic surgical wound infection. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RF, Kushner SR. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. Expression cloning and periplasmic orientation of the Francisella novicida lipid A 4′-phosphatase LpxF. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9321–9330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C, Trent MS. Biosynthesis and Export of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2014;83:99–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsor GL, Lam DKW, Fleming L, Lo R, Whiteside MD, Yu NY, et al. Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D596–600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wösten MMSM, Kox LFF, Chamnongpol S, Soncini FC, Groisman EA. A Signal Transduction System that Responds to Extracellular Iron. Cell. 2000;103:113–125. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. Lipid A modifications characteristic of Salmonella typhimurium are induced by NH4VO3 in Escherichia coli K12. Detection of 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine and palmitate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18503–18514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.