Abstract

Chemotaxis is vital cellular movement in response to environmental chemicals. Unlike the canonical chemotactic pathway in Escherichia coli, Rhodobacter sphaeroides has both transmembrane and cytoplasmic sensory clusters, with the latter possibly interacting with essential components in the electron transport system. However, the effect of the cytoplasmic sensor and the mechanism of signal integration from both sensory clusters remain unclear. Based on a minimal model of the chemotaxis pathway in this species, we show that signal integration at the motor level produces realistic chemotactic behaviour in line with experimental observations. Our model also suggests that the core pathway of R. sphaeroides, at least its ancestor, may represent a metabolism-dependent selective stopping strategy, which alone can steer cells to favourable environments. Our results not only clarify the potential roles of the two sensory clusters but also put in question the current definitions of attractants and repellents.

Keywords: chemotaxis, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, simulations, metabolism

1. Introduction

Chemotaxis is biased random walk in gradients of beneficial or toxic chemicals, until relevant concentrations are optimal. In bacteria, chemotactic behaviour requires flagellar rotation and two-component signal transduction systems that comprises histidine kinases and response regulators. Unlike the well-known example of chemotaxis in Escherichia coli, some bacteria including Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Bacillus subtilis have more complicated signalling systems composed of multiple homologues of E. coli chemotaxis proteins [1–3].

Although it is widely believed that metabolism does not feedback to chemotactic behaviour, recent research challenges this prevailing concept of metabolism-independent chemotaxis by raising the issue that chemotaxis is constantly affected by the metabolic state. For instance, a number of chemotaxis proteins in R. sphaeroides may be involved in intracellular metabolic sensing [4,5], thus referring to this motility as metabolism-dependent chemotaxis. In this paper, we aim to gain insights into metabolism-dependent chemotaxis, specifically in R. sphaeroides, by mathematically modelling its minimal signal transduction pathway.

1.1. Metabolism-independent chemotaxis

The chemotaxis signalling pathway of E. coli is best-understood and considered largely independent of metabolism where cells only sense external attractants and repellents with membrane-bound receptor clusters [6,7]. As depicted in figure 1a, upon ligand binding to the membrane-bound chemoreceptors, histidine kinase CheA autophosphorylates and transfers phospho groups to its cognate response regulator CheY, allowing phosphorylated CheY (CheY-P) to interact with the flagellar motor switch complex, resulting in clockwise rotation of flagella and tumbling motion of cell. Without a chemical stimulus, CheZ rapidly dephosphorylates CheY, and flagella switch to default counter-clockwise rotation, causing the cell to run. Enzymes CheR and CheB enable recovery of the receptor activity to its pre-stimulus level by methylation and demethylation of the receptors, respectively [9,10]. Hence, the chemoreceptors are known as methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs). Meanwhile, CheW is required in chemotactic signalling transduction, as it links chemoreceptors and CheA [11].

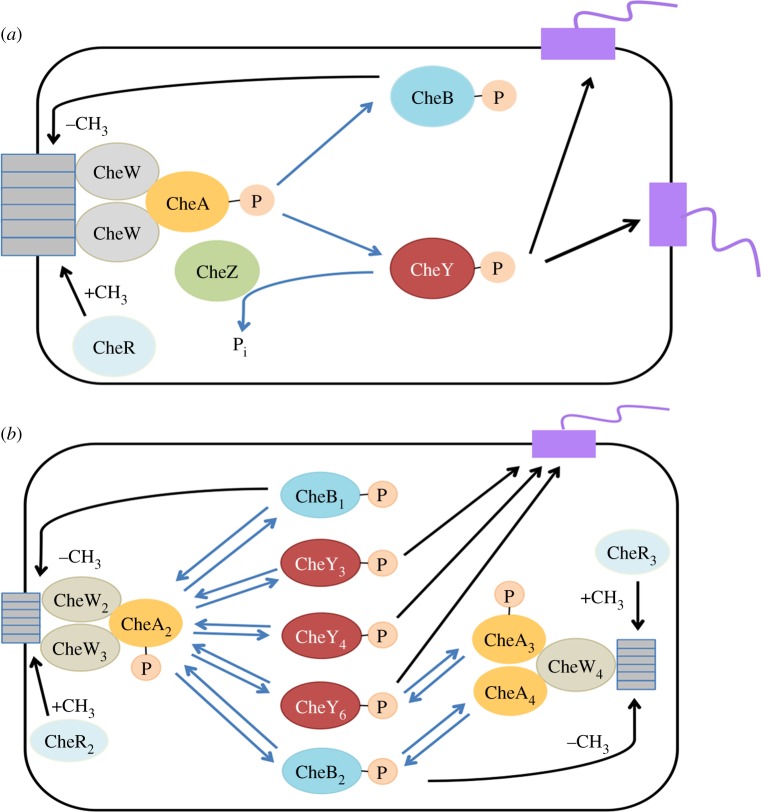

Figure 1.

Chemotaxis signalling pathway in (a) E. coli and (b) R. sphaeroides (adapted from [8]). Blue arrows indicate phosphotransfer. (a) In E. coli, attractant binding to the transmembrane receptors inhibits CheA autophosphorylation. Subsequently, CheA-P transfers the phospho group to CheY, allowing CheY-P to bind flagellar motors for ‘tumbling’. CheZ phosphatase dephosphorylates CheY-P to enable ‘running’. CheR and CheB are antagonistic proteins that fine-tune sensitivity of the receptors by methylation and demethylation, respectively. (b) In R. sphaeroides, transmembrane chemoreceptors can sense external concentration of attractants, and the cell presumably responds by CheA2 autophosphorylation. CheA2-P then transfers phospho groups to a range of response regulators including CheY3, CheY4, CheY6, CheB1 and CheB2. Cytosolic chemoreceptors may sense the internal metabolic state. When cytosolic cluster is activated, CheA3 and CheA4 cooperate to phosphorylate CheY6 and CheB2. (Online version in colour.)

In E. coli and some other species, dedicated receptors for oxygen, various sugars and some amino acids have been identified [12–14]. Chemotaxis towards ligand analogues supports the proposition that attractant sensing is only through the transmembrane chemoreceptors. Similarly, repellents like some weak acids may be sensed through these MCPs at different binding sites [15,16]. For instance, acids are also sensed in the cytosolic linker region of Tsr and Tar receptors at the end of the HAMP domain [17].

Although chemotaxis to some attractants supports metabolism by leading cells to nutrients, bacterial movement is not affected by the metabolic state in the cell, due to lack of signal feedback loops from metabolism pathways to the chemotaxis proteins. This insensitivity to metabolic states allows bacteria to navigate to the maximum concentration of attractants.

1.2. Metabolism-dependent chemotaxis

In contrast to the widely accepted concept of metabolism-independent chemotaxis, evidence for metabolism-dependent chemotaxis is raised in many species such as R. sphaeroides, Azospirillum brasilense and Helicobacter pylori [18–20]. In these bacteria, the metabolic state has an on-going effect on chemotaxis, with evidence including:

— chemotaxis to some attractants requires partial metabolism of these attractants [21,22];

— the role of a chemical can switch between attractant and repellent, depending on growth conditions and the chemical concentration [8,23];

— inhibiting the metabolic pathway of one attractant abolishes chemotaxis to this attractant, while bacteria still have chemotactic behaviour towards other attractants [22,24]; and

— inhibitors of metabolic pathways can act as repellents [18].

1.3. Chemotaxis pathway in Rhodobacter sphaeroides

Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a purple non-sulfur bacterium that can use a wide variety of energy sources depending on the availability in the environment. Its notably versatile metabolism stresses the essentiality of metabolic state to continuously affect chemotaxis. In fact, sensing of cellular metabolic state in this bacterium can be accomplished by an additional cytoplasmic sensory cluster, which is absent in metabolism-independent chemotactic bacteria [25]. This cytoplasmic cluster is thought to cooperate with the transmembrane chemosensory cluster and together determine the response of the single unidirectional flagellar rotation, i.e. rotating or stopping [26,27]. The resulting response of the cell is either a run or a stop. During the stops, the bacteria presumably randomly reorientate through Brownian motion [28], resembling a tumble in E. coli.

Another important characteristic of R. sphaeroides chemotaxis is the presence of two types of flagella composed of different proteins Fla1 and Fla2 controlled by different chemotaxis proteins [4,26,29], but only Fla1 is exclusively expressed in wild-type cells in the laboratory [30]. Phylogenetic studies indicate that Fla2-mediated chemotaxis might be evidence for an ancient chemotaxis pathway [30]. Therefore, we focus on Fla1-mediated chemotaxis in this paper.

Fla1-mediated chemotaxis involves both transmembrane and cytoplasmic sensory clusters (figure 1b) [8]. CheW2, CheW3 and CheW4 in these clusters are responsible for coupling the CheAs with dedicated MCPs and fine-tuning chemoreceptor sensitivity by accepting or donating methyl groups [31]. Upon binding of external attractants to the transmembrane chemoreceptors, CheA2 autophosphorylates and passes the phospho group onto response regulators CheY3, CheY4, CheY6, CheB1 and CheB2 [32]. However, binding affinities of chemoeffectors at the transmembrane receptors have not been measured.

Although the cytoplasmic cluster is believed to sense the metabolic state, specific ligands have not been experimentally established [8], except for some dicarboxylic acids such as succinate and propionate, which are sensed by TlpT [33]. It is possible that molecules involved in respiration, especially in the electron transport system (ETS) may activate cytoplasmic CheAs (CheA3 and CheA4) [23]. CheA3 and CheA4 differ from CheA2 because cytoplasmic CheAs only phosphorylate CheY6 and CheB2. Moreover, CheA3 and CheA4 do not autophosphorylate, but first form a heterodimer (CheA3/CheA4) that uses the kinase domain of CheA4 to phosphorylate the P1 domain of CheA3 [27]. There is additional complexity in this signalling pathway. For example, phosphorelay via CheB2 and multiple phosphorylation sites on CheY6 enable CheY6 to become a phosphate sink [34]. As phosphate groups from CheY3 and CheY4 can be transferred to CheY6, and CheA3 is able to quickly dephosphorylate CheY6 [35], it is reasonable that a CheZ homologue is absent in R. sphaeroides.

Recently, some researchers have modelled metabolism-based chemotaxis based on simple physical principles [36], while others have attempted to predict interactions between some chemotaxis proteins in R. sphaeroides [37]. So far there is no approach to simulating how the two sensory clusters contribute to bacterial movement. Here, we investigate a number of open questions, including signal transduction, integration of signals at the flagellar motor and the resulting chemotactic behaviour, using a minimal model of only the essential components in R. sphaeroides chemotaxis.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemotaxis pathway

The transmembrane and cytoplasmic sensory clusters are regarded as a metabolism-independent and a metabolism-dependent pathway, respectively. The former pathway only responds to extracellular ligand, whereas the latter senses the metabolic state, reflected by the amount of ATP. Minimal models for both pathways are constructed using ordinary differential equations, considering only the essential components involved, with details explained in the following paragraphs.

2.1.1. Metabolism-independent pathway

The essential structure of this pathway consists of transmembrane receptors, histidine kinase CheA2, response regulators CheY3 and CheY4, and motor, as shown in figure 2a. We regard CheY3 and CheY4 as one molecule CheY3,4 for simplicity, as they are functionally redundant [34]. The associated rate constants are demonstrated in table 1.

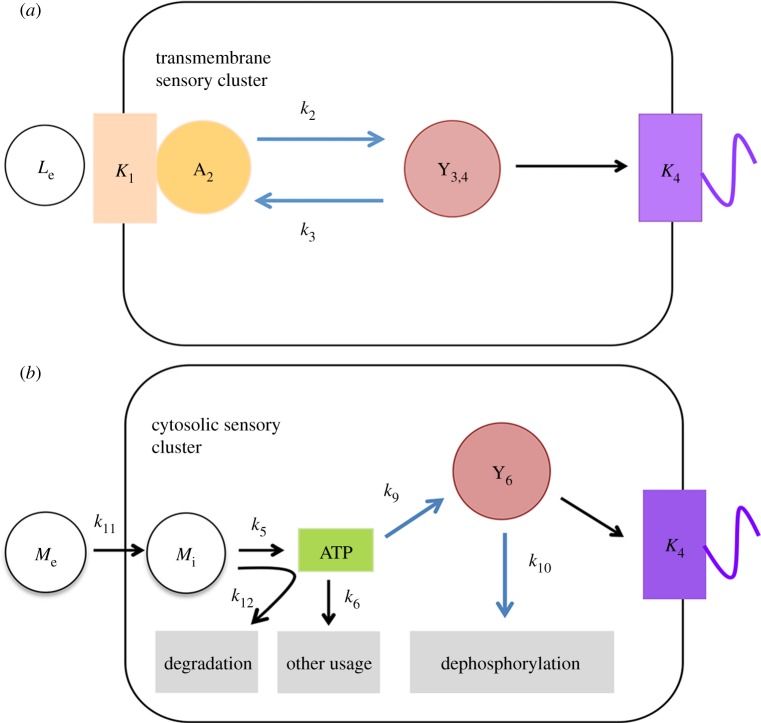

Figure 2.

Minimal model for R. sphaeroides (a) transmembrane and (b) cytosolic sensory clusters. Blue arrows indicate phosphotransfer. (a) In the transmembrane chemotaxis pathway model, CheA2 autophosphorylation is increased upon external ligand binding to transmembrane chemoreceptors (activated CheA2 is denoted as A2). Receptor activity is also dependent on ligand-binding constant K1. The amount of CheY3-P and CheY4-P (Y3,4) is dependent on A2, phosphorylation rate k2 and dephosphorylation rate k3. Binding of CheY3-P and CheY4P stops flagellar rotation, influenced by motor dissociation constant K4. (b) In the cytoplasmic chemotaxis pathway model, internal metabolite (Mi) transported from external environment (Me) with rate k11 is taken up and k12 catabolized, producing ATP with rate k5. Subsequently, ATP is used for indirect phosphorylation of CheY6 (CheY6-P denoted as Y6) with rate k9. Other usages of ATP include anabolism with rate k6. CheY6 can also be gradually dephosphorylated with rate k10. Binding of CheY6-P to motor leads to an increased probability of flagellar stopping, depending on motor binding constant K4. (Online version in colour.)

Table 1.

Parameters of the R. sphaeroides metabolism-independent pathway. The asterisk marks that the parameter value is adapted from [37].

| parameter | value | unit |

|---|---|---|

| K1 | 2.0 | μM |

| k2 | 0.6* | s−1 |

| k3 | 0.3 | s−1 |

| K4 | 0.5 | — |

| n | 2 | — |

| m1 | 8 | — |

The Ising-lattice model [38] and Monod–Wyman–Changeux [39,40] models suggest that receptors in clusters act cooperatively by allosterically activating or deactivating neighbouring receptor proteins. Here, we use the simplified Hill equation

| 2.1 |

with K1 being the ligand-binding rate constant, Le, the external attractant concentration and n, a Hill coefficient. This implies that external attractant binding increasing phosphorylation of CheA2. This is in contrast to observations in R. sphaeroides [41], but is meant to reflect an ancient selective stopping strategy [36] (see ‘Discussion’ section). The activated CheA2 phosphorylates CheY3,4, while changes in total phosphorylated CheY3,4 concentration are also affected by the available unphosphorylated CheY3,4, whose concentration is normalized by the total CheY3,4 concentration. Hence, the changes in phosphorylated CheY3,4 (denoted as Y3,4) is calculated as

| 2.2 |

with k2 and k3 being rate constants of phospho transfer and dephosphorylation, respectively. As a result of phosphorylated CheY3,4 binding to the flagellar motor, R. sphaeroides has a chance to stop flagellar rotation, with stopping probability

|

2.3 |

where K4 is a threshold parameter and m1 a Hill coefficient.

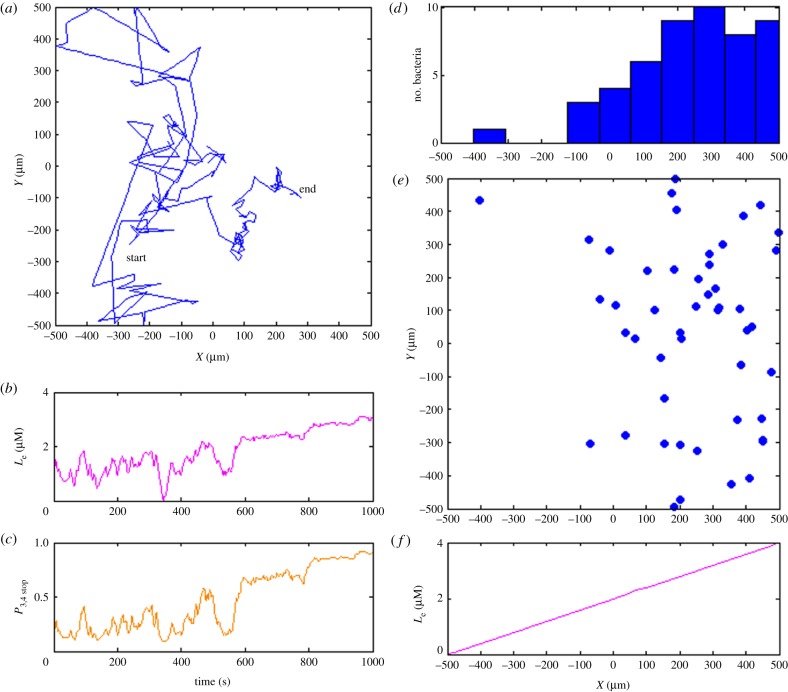

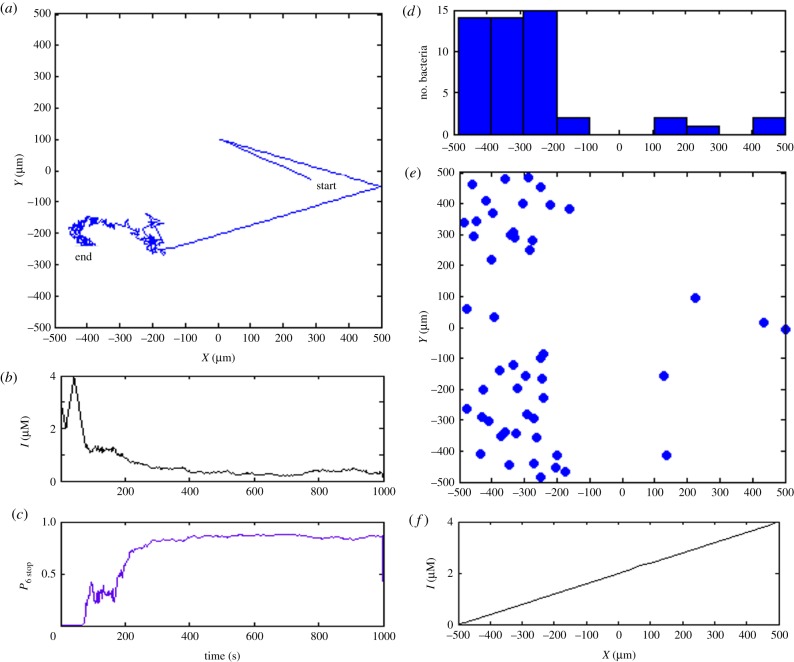

To summarize, in our model, an increase in environmental ligand level results in more phosphorylated CheA2, an increased concentration of phosphorylated CheY3,4, and eventually a higher stopping probability. With the presumed high sensitivity, the metabolism-independent pathway encourages the cell to run towards the maximum concentration of ligand. Figure 3 shows the simulated chemotactic behaviours based only on the metabolism-independent pathway (for simulation details, see §2.3).

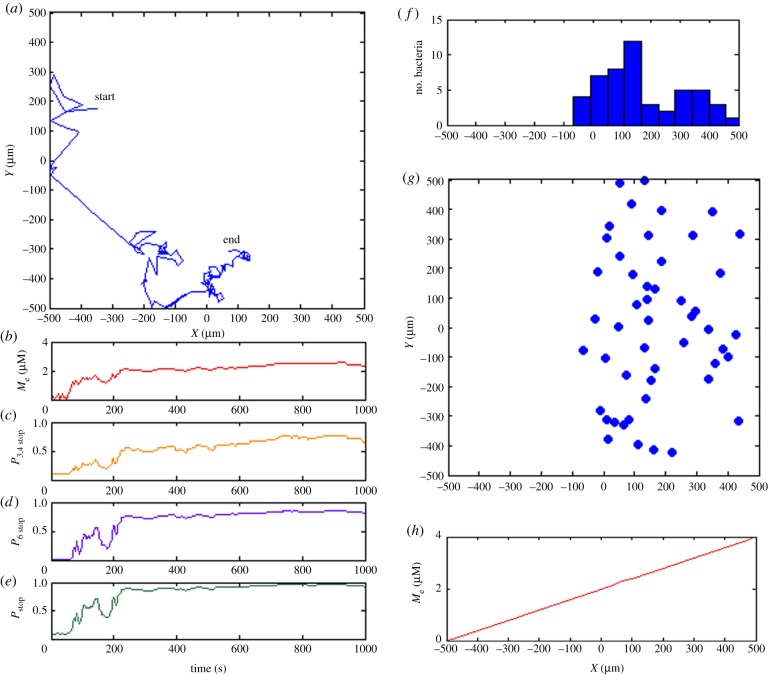

Figure 3.

Simulation of transmembrane cluster-mediated chemotaxis. (a) Trajectory of exemplar bacterium showing movement up the gradient from left to right in the simulation box. (b) Experienced local ligand concentration of simulated bacterium during 1000 s simulation period. (c) Stopping probability based only on the transmembrane sensory pathway. (d) The distribution of 50 independently bacteria along x-axis after 1000 s simulation time. (e) The final distribution of 50 simulated in silico bacteria. Almost all the simulated bacteria migrate to the area where external ligand is abundant. (f) The external ligand concentration increases linearly in x-direction from −500 to 500 µm. (Online version in colour.)

2.1.2. Metabolism-dependent pathway

In this model, we assume that the metabolic state is represented by the amount of ATP, as ATP is the most common and direct energy source in cells, and it is required for all phosphorylation reactions. For simplicity, histidine kinases CheA3 and CheA4 are not considered. Thus, the key components of the metabolism-dependent pathway include external and internal metabolite, ATP, CheY6 and the motor, as shown in figure 2b. The rate constants in this particular model are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of the R. sphaeroides metabolism-dependent pathway.

| parameter | value | unit |

|---|---|---|

| k5 | 43.90 | μM3 s−1 |

| k6 | 1 | s−1 |

| K7 | 3.8 | μM |

| k8 | 0.5 | (μM s)−1 |

| k9 | 0.6 | (μM s)−1 |

| k10 | 0.6 | s−1 |

| k11 | 0.5 | s−1 |

| k12 | 0.1 | (μM s)−1 |

| m2 | 8 | — |

| n0 | 3 | — |

| n1 | 2 | — |

The internal metabolite concentration Mi depends on the extracellular metabolite concentration Me as follows:

| 2.4 |

with k11 being the diffusion rate of metabolite across the membrane and k12, the catabolic rate of the metabolite. When transported inside cells, metabolite is catabolized to produce ATP, or inhibits ATP production if present at high level. Meanwhile, ATP production can also be inhibited at the presence of a metabolic inhibitor I. Here, the inhibitor is assumed to accelerate the rate of ATP degradation, resulting in

| 2.5 |

with k5 being the ATP production rate; k6, the ATP usage rate; K7, the threshold parameter that allows saturation of ATP production; k8, the inhibitory rate of metabolite; and n0 and n1 Hill coefficients. Apart from supporting cellular activities, ATP is also used to indirectly phosphorylate CheY6, with the concentration of phosphorylated CheY6 given as

| 2.6 |

with k9 and k10 the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation rate constants, respectively. Finally, binding of phosphorylated CheY6 at motor contributes to cell stopping, with the stopping probability given as

| 2.7 |

where K4 is a threshold and m2, a Hill coefficient.

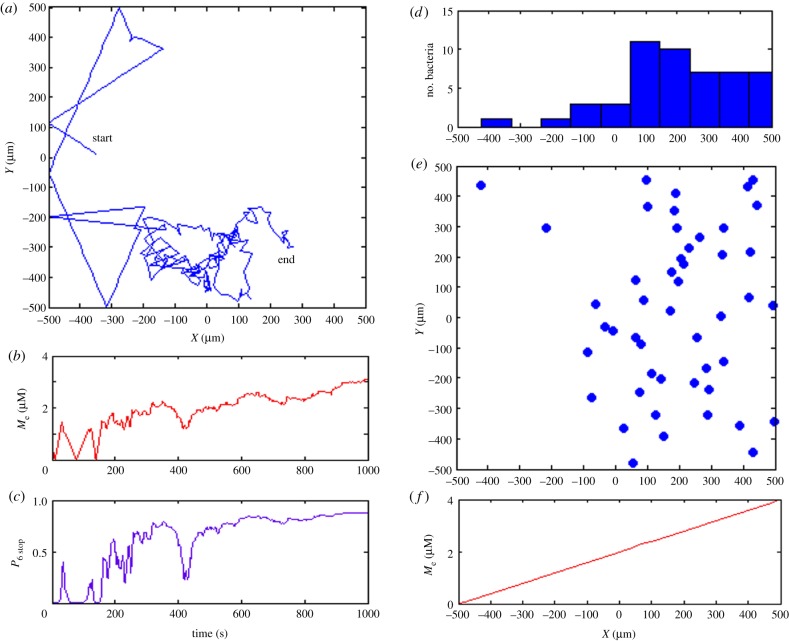

In summary, an increase in external metabolite concentration leads to ATP production, contributing to more phosphorylated CheY6 and consequently, a higher stopping probability. Hence, this pathway allows migration to places where optimal metabolism is achieved. Figure 4 shows the simulated chemotactic behaviours based only on the metabolism-dependent pathway.

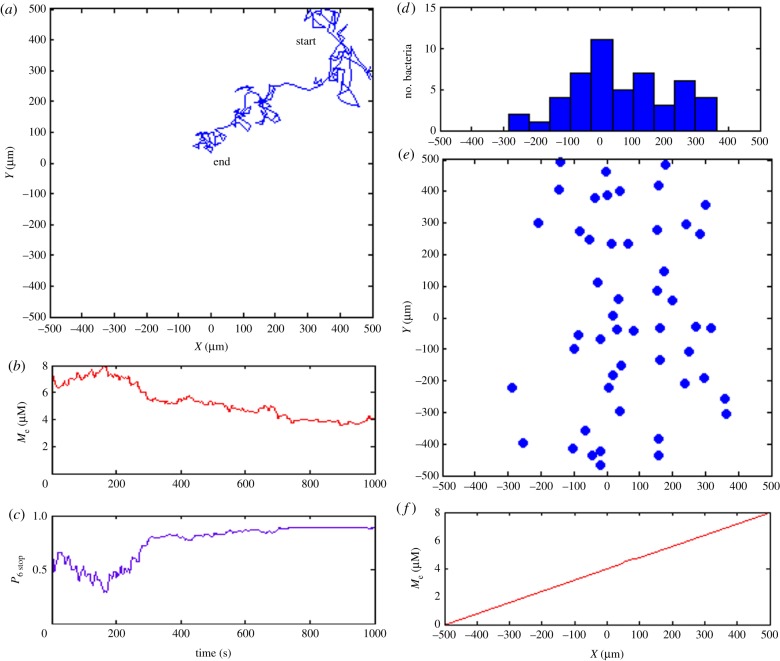

Figure 4.

Simulation of cytosolic cluster-mediated chemotaxis. (a) Exemplar trajectory of in silico bacterium in simulation box. (b) Local external metabolite concentration during 1000 s simulation. (c) Stopping probabilities resulting from cytoplasmic signalling cascade show saturation of the signal when external metabolite concentration is intermediate or high. (d) Distribution of 50 independently bacteria along x-axis at the end of the simulation shows that the majority of simulated bacteria accumulated at positive x-coordinates. (e) Final distribution of 50 simulated in silico bacteria, showing that bacteria move towards metabolites. (f) External metabolite concentration increases linearly in x-direction from −500 to 500 µm. (Online version in colour.)

As kinetic studies of the biochemical reactions are very limited, some rate constants were motivated by previous studies [37], while others were adjusted for convenience of the simulations to avoid saturation in the simulation box as adaptation was neglected.

2.2. Signal integration

As R. sphaeroides has a run-or-stop motor, the sum of running and stopping probabilities from each cluster is one. Hence, the following equation is obtained

| 2.8 |

Assuming that integration of signals from both sensory clusters occurs only at the flagellar motor, we propose a modified OR logic gate that integrates the probability resulting from each pathway, with the integrated stopping probability calculated as

| 2.9 |

Equation (2.9) is obtained by expansion and extraction of the factors containing stopping probabilities from equation (2.8).

2.3. Bacterial movement

Based on the Euler method, R. sphaeroides is simulated to move or stop, determined by the integrated stopping probability at each time step, i.e. each second in our simulations. Bacterial movement is implemented by comparing the integrated stopping probability, Pstop, with a random number between 0 and 1.

When stopped, the simulated bacteria randomly re-orientate around the two-dimensional space, mimicking in vivo behaviour [28]. In the running mode, bacteria orient in the same direction, α, as in the previous step and run 20 μm in the simulation box. The speed 20 μm s−1 was chosen based on experimental data of R. sphaeroides [42]. Therefore, the displacements along the x- and y-axes are x = 20 · cos (α) and y = 20 · sin (α), in units of micrometres.

All bacteria are simulated within a box of 50 × 50 μm. Meanwhile, reflecting boundary conditions are applied to prevent loss of bacteria within the box. To observe the collective chemotactic behaviour, 50 in silico bacteria are simulated independently with random starting points within the simulation box. The cellular signal levels are updated for each iteration to calculate the new stopping probability. Ultimately, the initial and final distributions of bacteria along the appropriate axes are compared in each simulation using the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistical test.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation 1: chemotaxis towards a chemical sensed by both sensory clusters

This simulation is inspired by several experimental observations that chemotaxis to some chemicals requires transport and metabolism of these chemicals [21,43,44]. Here, we test R. sphaeroides chemotactic behaviours towards a transmembrane receptor ligand that can also be converted to ATP. The ligand concentration increases linearly from left to right in the simulation box.

As shown in figure 5, the stimulated bacterium tumbles around high attractant concentrations, as the integrated stopping probability, Pstop, levels off at around 0.9 after 200 s. This movement pattern also applies to the other R. sphaeroides bacteria, as all the bacteria started from random positions clearly accumulated around high concentrations. The KS test proves the significant difference between the final and the initial distribution (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Simulation 1: chemotaxis towards a chemical sensed by both sensory clusters. (a) Exemplar trajectory in simulation box. (b) Experienced chemical concentration. (c) The stopping probability contributed by the transmembrane sensory pathway gradually increases as chemical concentration increases. (d) The stopping probability resulting from the cytoplasmic sensory cluster increases more significantly as the chemical concentration increases. (e) The integrated stopping probability eventually approaches 1 as the cytoplasmic sensory cluster almost saturates. (f) The distribution of 50 simulated bacteria along x-axis shows that the bacteria favour medium attractant concentrations. (g) Corresponding endpoints of bacteria. (h) Attractant concentration increases linearly in positive x-direction. (Online version in colour.)

3.2. Simulation 2: a metabolite can switch from an attractant to a repellent at very high concentration

As observed in Simulation 1, many bacteria do not move to the maximum attractant concentration. Such behaviour is also documented in aerotaxis. In response to an oxygen concentration gradient, R. sphaeroides returns to medium concentrations, forming a band [45]. To explore the reason for this behaviour, we conduct another simulation in which we allow for an even larger concentration range. In this case, it is assumed that only cytoplasmic cluster can sense the metabolite, which is set up to sharply increase in concentration along x-axis.

Interestingly, as shown in figure 6, the bacterium immediately returns to the middle of the box once it faces extreme concentrations of metabolite. By contrast, tumble motion dominates in the middle of the box, as directed by a higher stopping probability that resulted from the cytoplasmic sensory pathway. The behavioural pattern along the x-axis explains how multiple bacteria form a band in the middle of the box. The KS test supports that the initial and eventual cell distribution along the x-axis significantly differ (p < 0.01). A minor number of cells are found in the very right end of the box where the attractant concentration is highest. These, however, are eventually also trapped in the middle of the box.

Figure 6.

Simulation 2: a metabolite can switch from an attractant to a repellent at very high concentration. (a) Exemplar trajectory showing more running at the right side of the simulation box, and more tumbling in the middle of the box. (b) The experienced local external metabolite concentration indicates that the bacterium in (a) migrated from a high external metabolite concentration area to a medium concentration area. (c) As the bacterium in (a) moves to a medium metabolite concentration, the signal from cytoplasmic sensory cluster saturates. (d) The distribution of 50 simulated independent bacteria clearly exhibits accumulation in the middle of the box. (e) Corresponding endpoints of 50 trajectories. (f) The range of the metabolite concentration is twice as large as in the previous simulations in figure 5. (Online version in colour.)

3.3. Simulation 3: chemotaxis towards two functionally different chemicals

Rhodobacter sphaeroides has been shown to perform chemotaxis towards two functionally similar chemicals [46]. Additionally, bacteria may also need to simultaneously sense and chemotaxis towards functionally different beneficial molecules such as enzyme cofactors and carbon sources, assuming differential functionality means that absorption of the chemical leads to direct alterations in energy production. For example, the transmembrane chemoreceptor ligand may not directly contribute to producing ATP, while cytoplasmic receptor TlpT can sense some dicarboxylic acids that are commonly used as carbon source [33]. However, previous modelling of chemotaxis at the molecular level has only used one concentration gradient at a time [47], and there is currently no published investigation about chemotaxis towards functionally different chemicals. Here, we test if the simulated cells can respond to gradients of two functionally different chemicals.

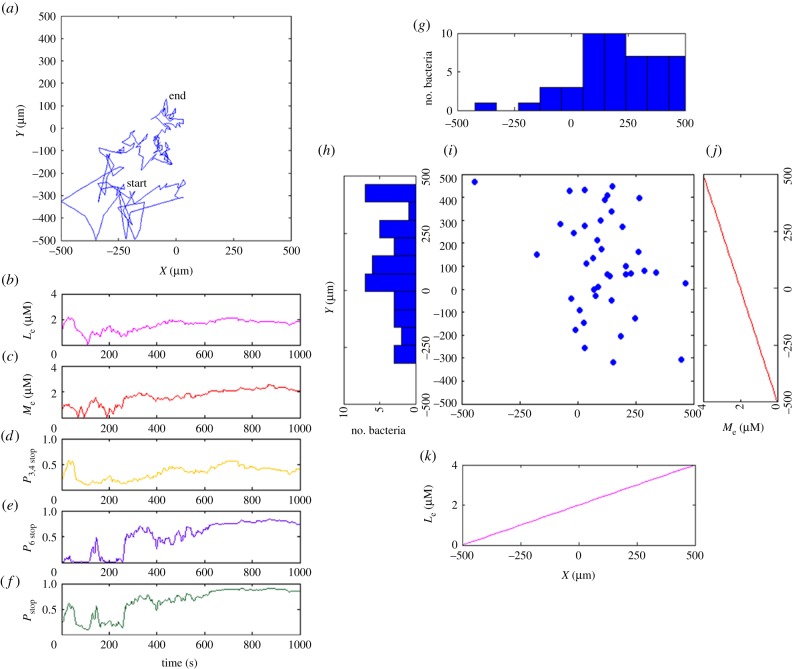

As shown in figure 7, bacteria favour the region where both attractants are relatively abundant, although they do not tend to explore maximal concentrations of both external ligand and metabolite. This is due to the saturation of both chemotaxis pathways, and corresponds to our other simulations that bacteria stop before reaching the highest concentration regions. Statistical analysis by the KS test shows a change in cell distribution along both axes after 1000 s is significant (x-axis p < 0.01; y-axis p < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Simulation 3: chemotaxis towards two functionally different chemicals. (a) Exemplar trajectory showing migration from the bottom-left to the middle of the box. (b,c) The bacterium in (a) moves up both ligand and external metabolite concentration gradients. (d,e) The stopping probabilities contributed by both the transmembrane and cytosolic sensory pathways gradually increase as the ligand and metabolite concentrations increase. (f) The stopping probability increases due to the increase in the signal levels from both sensory clusters. (g–i) Simulation of 50 independent bacteria indicates that they are able to seek both higher external ligand and metabolite concentrations using different sensory pathways. (j) Metabolite concentration is proportional to x. (k) Ligand concentration is proportional to y. (Online version in colour.)

3.4. Simulation 4: metabolic inhibitors can block chemotaxis towards the dedicated metabolite

Experiments have shown that inhibition and artificial mutation of key components in the metabolic pathway can abolish chemotaxis to that attractant. For example, methionine sulfoximine that inhibits ammonia assimilation can significantly interrupt chemotaxis to ammonia [43]. In addition, knocking out fructose metabolic pathway blocks chemotaxis towards fructose but not other attractants such as succinate [22]. Here, an inhibitor that blocks the metabolic pathway sensed by the cytoplasmic sensory cluster is evenly distributed (2 μM) across the simulation box. Ligand and metabolite concentrations are the same as in Simulation 3, with the results presented in figure 8.

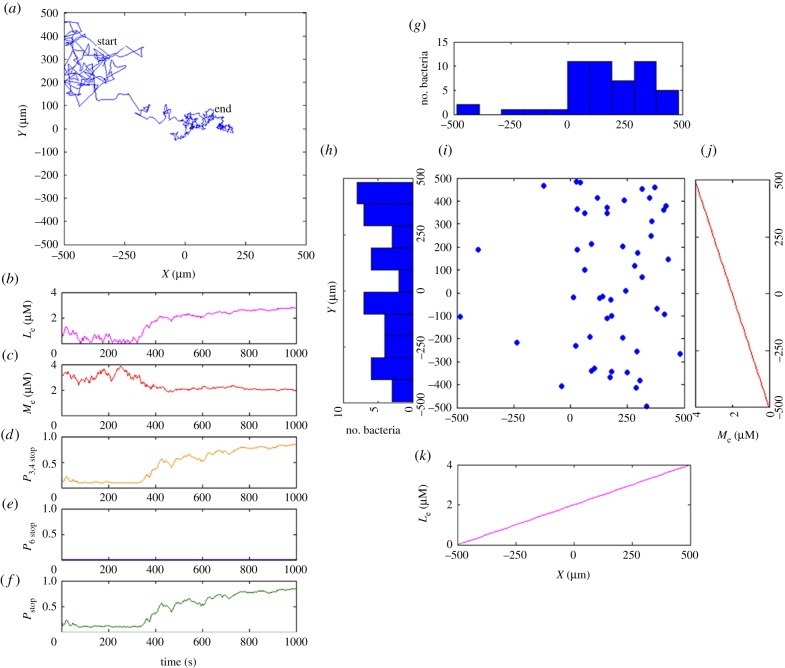

Figure 8.

Simulation 4: metabolic inhibitors can block chemotaxis towards the dedicated metabolite. The inhibitor is present evenly in the simulation box (with concentration 2 μM, not shown in the figures). (a) Exemplar bacterium showing migration from the top-left to the bottom-right in the simulation box. (b) The bacterium in (a) experiences an increase in ligand concentration. (c) The bacterium does not seek external metabolite. (d) The signal level in transmembrane sensory cluster becomes stronger as ligand concentration increases. (e) The stopping probability from the cytosolic sensory pathway remains almost zero, due to the constant inhibitory effect from the evenly distributed inhibitor. (f) The stopping probability only depends on the signal from transmembrane sensory cluster. (g–i) The distribution of 50 simulated bacteria along the x-axis shows that they seek high ligand concentrations, while being randomly distributed along the y-axis. (j) Linear metabolite gradient in x-direction. (k) Linear ligand gradient in y-direction. (Online version in colour.)

The inhibitor can completely block the signalling at the cytoplasmic cluster. Based on the OR gate algorithm (eqn (2.11) in Methodology), the stopping probability, in this case, equals the stopping probability resulting from signalling by the transmembrane sensory cluster. Thereafter, the in silico bacteria show more running motion towards high ligand concentrations. According to the distribution of 50 R. sphaeroides, the metabolic inhibitor has no effect on chemotaxis to ligand (p < 0.02), but can significantly interrupt chemotaxis to the metabolite, i.e. there is no significant difference between initial and final distribution of bacteria (p > 0.84).

3.5. Simulation 5: metabolic inhibitors can act as repellents

In other bacteria like A. brasilense, inhibitors including oxidized quinones that interrupt metabolic pathways actually act as repellents [18]. Similar experiments have not been conducted for R. sphaeroides. Thus, we would like to theoretically test whether an inhibitor can act as a repellent in this species. In this simulation, only the cytoplasmic sensory cluster is tested, as the inhibitor acting on the metabolic pathway does not directly affect the transmembrane sensory cluster. The control for this experiment is the bacteria distribution in presence of a constant metabolite concentration and absence of inhibitor, as shown in figure 9.

Figure 9.

Simulation 5: metabolic inhibitors can act as repellents. In this simulation, the metabolite is evenly distributed in the simulation box (figure not shown). (a) Exemplar trajectory showing that bacterium runs away from high inhibitor concentrations at the right in the simulation box, and that it stops at the left of the simulation box. (b) Within 1000 s simulation time, the bacterium in (a) avoids the inhibitor. (c) The signal from cytoplasmic sensory pathway increases significantly as the local inhibitor concentration drops. (d) The distribution of 50 simulated bacteria along the x-axis evidently indicating that most bacteria avoid the inhibitor. A few bacteria are observed at area where inhibitor concentration is high, but they will eventually join the others. (e) Trajectory endpoints of 50 in silico bacteria. (f) Linear inhibitor gradient in x-direction. (Online version in colour.)

The results show that compared to the randomly distributed bacteria in the control group, bacteria facing the metabolism inhibitor favour areas with low inhibitor concentration. Also there is a statistically significant difference between the cell distribution in control and test groups (p < 0.01). This is because the inhibitor reduces synthesis of ATP, which leads to less phosphorylated CheY6, encouraging bacteria to swim away from the inhibitor. When bacteria are distant from the inhibitor, the stopping probability resulting from high cytoplasmic signalling level approaches 1, contributing to flagellar stopping.

4. Discussion

Bacterial chemotaxis has been traditionally studied independently from metabolism. However, recent genomic studies show that metabolism-dependent chemotaxis in species like R. sphaeroides may be achieved through metabolic sensing by the cytoplasmic chemoreceptors and possibly integration of signals from both transmembrane and cytoplasmic sensory pathways. Here, we have provided a novel mathematical modelling approach to the unsolved problem of cytoplasmic sensory pathway signalling and integration of both sensory cluster signals in R. sphaeroides. Based on the minimal model where only essential molecules are considered, the simulations agree with available qualitative data in literature. Quantitative data is not used to compare with simulation results due to their limited availability.

An advance of this model is the cooperation of metabolic sensing with classic metabolism-independent chemotaxis. Previously, it was suggested that the signal integration site in R. sphaeroides might be CheA2, as deletion of CheA2 removes tactic behaviour [25]. Our model proposes an OR gate for integration at the motor level, producing realistic bacterial behaviours while reducing the complexity of cross-talk between the different pathways. However, there are two shortcomings of our minimal model. First, we neglect adaptation of both receptor clusters to avoid additional cross-talk via uncharacterized reactions. A downside of this is that our model parameters require some fine-tuning. Second, we technically do not implement a run-and-tumble chemotaxis strategy, but a simpler selective stopping strategy. This potentially ancient strategy allows cells to simply swim until they find favourable conditions and then stop [36]. We speculate that receptors of the cytoplasmic cluster of R. sphaeroides may have used such a strategy as CheY6 dominates over other CheYs, i.e. CheY6 is the key CheY in controlling the flagellar motor, and thus could have implemented such metabolism-based chemotaxis. Note that our minimal model without cross-talk between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic clusters requires an OR gate to produce simultaneous chemotaxis to both an external attractant and a metabolite. However, when allowing for the possibility that the transmembrane and cytoplasmic signalling pathways are interlinked by adaptation pathways, an AND gate also may work.

Our simulation results raise the very interesting question of how to define an attractant or a repellent, because they can be interchangeable. Simulations 1 and 2 suggest that a metabolite, when present at certain concentrations, can cause signal saturation and may even switch to a repellent, corresponding to the microaerophilic and microaerophobic behaviours observed in aerotaxis [45]. Precise definition of attractant and repellent may be more complicated as the role of a metabolite also depends on cell culture conditions [48,49], so that photosynthetically grown R. sphaeroides may regard oxygen as a repellent, as coexistence of light and oxygen can produce fatal reactive oxidative species.

In addition, there is experimental evidence that inhibition of metabolic pathways abolishes chemotaxis towards this metabolite. Based on the modelling (Simulation 4), we predict that the inhibitor can indeed act as a repellent for R. sphaeroides. In fact, experiments on other species like A. brasilense, whose chemotaxis mechanism also depends on metabolism, imply that cells avoid exposure to inhibitors of the ETS [18]. Hence, it is realistic to suggest that the role of a chemical may be defined through its effect on energy generation.

The results of several simulations stress the importance of the cytoplasmic sensory cluster, as it can nearly determine cell movement by itself (Simulations 1, 3 and 5). There are several observations that support this idea. Firstly, sensitivity of the cytoplasmic sensory cluster can be increased by splitting a kinase into an ATP binding protein (CheA4) and a phosphatase (CheA3), and joining them together as a heterodimer [50]. Secondly, experimental observations have indicated the ability of CheY6 to stop the flagellar motor alone, probably due to multiple phosphorylation sites [34]. Finally, some attractants like fumarate may not be sensed through the transmembrane sensory cluster at all. Instead, furmarate acts on flagellar rotation via a respiratory protein fumarate reductase [51], which can potentially be sensed by the cytoplasmic sensory cluster.

As simulated cells mimic chemotaxis observed in wild-type R. sphaeroides, even when the transmembrane sensory pathway is not considered (Simulation 2), one might wonder why a transmembrane sensory cluster is necessary at all? As R. sphaeroides shows strong chemotaxis towards many different sugars, it may be unrealistic to possess different chemoreceptors for each specific ligand in the membrane [22]. This evidence suggests that carbohydrates may not be sensed through the classic transmembrane MCP pathway. However, other experiments indicate that both sensory pathways must work together to support chemotactic behaviours [34,52]. Some researchers believe having many CheY proteins may allow the molecules to compete for binding, even without actually stopping the flagellar rotation [53]. Therefore, upon external ligands binding to receptors, phosphorylated CheY3 and CheY4 may only compete with phosphorylated CheY6 for binding to the flagellar motor switch complex, without stopping flagellar rotation themselves. Of course, sensing toxins by transmembrane receptors avoids having to take them up prior to sensing. Further biochemical research is necessary to identify the ligands of transmembrane chemoreceptors, as well as the roles of different chemotaxis proteins.

Our simulation results suggest that ATP may play a key role in chemotaxis signalling. Indeed, ATP is both an essential reactant for phosphorylation of the chemotaxis proteins and a product of energy generation. Its ability to change rapidly in R. sphaeroides provides the potential to affect chemotaxis significantly [54]. Note, however, that our minimal model of metabolism-based chemotaxis does not model sensing of the metabolites by the cytoplasmic cluster explicitly. This reflects the idea that our model represents an ancient version of R. sphaeroides chemotaxis. Hence, to avoid large changes in intracellular ATP levels, which may be detrimental for many other aspects of cellular functioning, the cytoplasmic sensory cluster may have evolved to sense some metabolites directly, and not indirectly via ATP.

Current experimental data suggest that metabolism-dependent chemotaxis may be more complex than previously thought, owing to differential gene expression in different environments. For example, PrrB/PrrA two-component system up-regulates photosynthesis in R. sphaeroides, and the expression is stimulated by low oxygen conditions [55]. This implies that at very low concentration, oxygen may no longer be an attractant, but may cause bacteria to start phototaxis. The coupling between gene expression and tactic response can be very beneficial to cells by enhancing adaptation to their changing environment.

Unfortunately, using a more realistic model to simulate complex metabolism-dependent chemotaxis is still limited by the lack of quantitative experimental data and kinetic studies. For example, some reactions in the signalling pathways, the nature of the ligands of the cytoplasmic receptor cluster, the binding sites of the CheY proteins on the motor switch complex, the origin of signal integration, cross-talk and synchronization of the two of sensory pathways are yet unclear. A stronger collaboration between experimentalists and theoretical systems biologist is required to improve our understanding of metabolism-dependent chemotaxis.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for helpful discussions with Judy Armitage. This work was initiated during S.F.'s final-year undergraduate project.

Funding statement

R.E. thankfully acknowledges funding from the ERC Starting grant no. 280492-PPHPI.

References

- 1.Rosario MML, Fredrick KL, Ordal GW, Helmann JD. 1994. Chemotaxis in Bacillus subtilis requires either of 2 functionally redundant CheW homologs. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2736–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward M, Bell A, Hamblin P, Packer H, Armitage J. 1995. Identification of a chemotaxis operon with 2 CheY genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 17, 357–366. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020357.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2008. Rhodobacter sphaeroides: complexity in chemotactic signalling. Trends Microbiol. 16, 251–260. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2008.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah DSH, Porter SL, Martin AC, Hamblin PA, Armitage JP. 2000. Fine tuning bacterial chemotaxis: analysis of Rhodobacter sphaeroides behaviour under aerobic and anaerobic conditions by mutation of the major chemotaxis operons and cheY genes. EMBO J. 19, 4601–4613. ( 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4601) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin AC, Gould M, Byles E, Roberts MAJ, Armitage JP. 2006. Two chemosensory operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides are regulated independently by sigma 28 and sigma 54. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7932–7940. ( 10.1128/JB.00964-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2004. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 1024–1037. ( 10.1038/nrm1524) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenbach M, Constantinou C, Aloni H, Shinitzky M. 1990. Repellents for Escherichia coli operate neither by changing membrane fluidity nor by being sensed by periplasmic receptors during chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 172, 5218–5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2011. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 153–165. ( 10.1038/nrmicro2505) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goy MF, Springer MS, Adler J. 1977. Sensory transduction in Escherichia coli—role of a protein methylation reaction in sensory adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 74, 4964–4968. ( 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4964) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clausznitzer D, Oleksiuk O, Lovdok L, Sourjik V, Endres RG. 2010. Chemotactic response and adaptation dynamics in Escherichia coli. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000784 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000784) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borkovich KA, Kaplan N, Hess JF, Simon MI. 1989. Transmembrane signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis involves ligand-dependent activation of phosphate group transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1208–1212. ( 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bibikov SI, Biran R, Rudd KE, Parkinson JS. 1997. A signal transducer for aerotaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179, 4075–4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grebe TW, Stock J. 1998. Bacterial chemotaxis: the five sensors of a bacterium. Curr. Biol. 8, R154–R157.. ( 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)00098-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkinson JS, Ames P, Studdert CA. 2005. Collaborative signaling by bacterial chemoreceptors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 116–121. ( 10.1073/pnas.092071899) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slonczewski JL, Macnab RM, Alger JR, Castle AM. 1982. Effects of pH and repellent tactic stimuli on protein methylation levels in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 152, 384–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto K, Macnab RM, Imae Y. 1989. Repellent response functions of the Trg and Tap chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 72, 383–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umemura T, Matsumoto Y, Ohnishi K, Homma M, Kawagishi I. 2002. Sensing of cytoplasmic pH by bacterial chemoreceptors involves the linker region that connects the membrane-spanning and the signal-modulating helices. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1593–1598. ( 10.1074/jbc.M109930200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexandre G, Greer SE, Zhulin IB. 2000. Energy taxis is the dominant behavior in Azospirillum brasilense. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6042–6048. ( 10.1128/JB.182.21.6042-6048.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandre G. 2010. Coupling metabolism and chemotaxis-dependent behaviours by energy taxis receptors. Microbiology 156, 2283–2293. ( 10.1099/mic.0.039214-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schweinitzer T, Josenhans C. 2010. Bacterial energy taxis: a global strategy? Arch. Microbiol. 192, 507–520. ( 10.1007/s00203-010-0575-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole PS, Smith MJ, Armitage JP. 1993. Chemotactic signaling in Rhodobacter sphaeroides requires metabolism of attractants. J. Bacteriol. 175, 291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeziore-Sassoon Y, Hamblin PA, Bootle-Wilbraham CA, Poole PS, Armitage JP. 1998. Metabolism is required for chemotaxis to sugars in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiology 144, 229–239. ( 10.1099/00221287-144-1-229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romagnoli S, Armitage JP. 1999. Roles of chemosensory pathways in transient changes in swimming speed of Rhodobacter sphaeroides induced by changes in photosynthetic electron transport. J. Bacteriol. 181, 34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexandre G, Zhulin IB. 2001. More than one way to sense chemicals. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4681–4686. ( 10.1128/JB.183.16.4681-4686.2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamblin PA, Maguire BA, Grishanin RN, Armitage JP. 1997. Evidence for two chemosensory pathways in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 26, 1083–1096. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6502022.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter SL, Warren AV, Martin AC, Armitage JP. 2002. The third chemotaxis locus of Rhodobacter sphaeroides is essential for chemotaxis. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 1081–1094. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03218.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter SL, Armitage JP. 2004. Chemotaxis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides requires an atypical histidine protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54 573–54 580. ( 10.1074/jbc.M408855200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armitage JP, Macnab RM. 1987. Unidirectional, intermittent rotation of the flagellum of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 169, 514–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Campo AM, Ballado T, De la Mora J, Poggio S, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2007. Chemotactic control of the two flagellar systems of Rhodobacter sphaeroides is mediated by different sets of CheY and FliM proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8397–8401. ( 10.1128/JB.00730-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poggio S, Abreu-Goodger C, Fabela S, Osorio A, Dreyfus G, Vinuesa P, Camarena L. 2007. A complete set of flagellar genes acquired by horizontal transfer coexists with the endogenous flagellar system in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3208–3216. ( 10.1128/JB.01681-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin AC, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2001. The roles of the multiple CheW and CheA homologues in chemotaxis and in chemoreceptor localization in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 1261–1272. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02468.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter SL, Armitage JP. 2002. Phosphotransfer in Rhodobacter sphaeroides chemotaxis. J. Mol. Biol. 324, 35–45. ( 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01031-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson S, Wadhams G, Armitage J. 2006. The positioning of cytoplasmic protein clusters in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8209–8214. ( 10.1073/pnas.0600919103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Martin AC, Byles ED, Lancaster DE, Armitage JP. 2006. The CheYs of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32 694–32 704. ( 10.1074/jbc.M606016200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter SL, Roberts MAJ, Manning CS, Armitage JP. 2008. A bifunctional kinase-phosphatase in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18 531–18 536. ( 10.1073/pnas.0808010105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egbert MD, Barandiaran XE, Di Paolo EA. 2010. A minimal model of metabolism-based chemotaxis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1001004 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tindall MJ, Porter SL, Maini PK, Armitage JP. 2010. Modeling chemotaxis reveals the role of reversed phosphotransfer and a bi-functional kinase-phosphatase. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000896 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000896) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duke TAJ, Bray D. 1999. Heightened sensitivity of a lattice of membrane receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10 104–10 108. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. 1965. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88–118. ( 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80285-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skoge ML, Endres RG, Wingreen NS. 2006. Receptor-receptor coupling in bacterial chemotaxis: evidence for strongly coupled clusters. Biophys. J. 90, 4317–4326. ( 10.1529/biophysj.105.079905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamadeh A, Roberts MAJ, August E, McSharry PE, Maini PK, Armitage JP, Papachristodoulou A. 2011. Feedback control architecture and the bacterial chemotaxis network. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1001130 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armitage JP, Pitta TP, Vigeant MA, Packer HL, Ford RM. 1999. Transformations in flagellar structure of Rhodobacter sphaeroides and possible relationships to changes in swimming speed. J. Bacteriol 181, 4825–4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poole PS, Armitage JP. 1989. Role of metabolism in the chemotactic response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides to ammonia. J. Bacteriol. 171, 2900–2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs MHJ, vanderHeide T, Tolner B, Driessen AJM, Konings WN. 1995. Expression of the gltP gene of Escherichia coli in a glutamate transport-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides restores chemotaxis to glutamate. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 641–647. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040641.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romagnoli S, Packer HL, Armitage JP. 2002. Tactic responses to oxygen in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5590–5598. ( 10.1128/JB.184.20.5590-5598.2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim M, Kim T. 2010. Diffusion-based and long-range concentration gradients of multiple chemicals for bacterial chemotaxis assays. Anal. Chem. 82, 9401–9409. ( 10.1021/ac102022q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldstein RA, Soyer OS. 2008. Evolution of taxis responses in virtual bacteria: non-adaptive dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000084 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armitage JP, Schmitt R. 1997. Bacterial chemotaxis: Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Sinorhizobium meliloti—variations on a theme? Microbiology 143, 3671–3682. ( 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3671) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kojadinovic M, Sirinelli A, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2011. New motion analysis system for characterization of the chemosensory response kinetics of Rhodobacter sphaeroides under different growth conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4082–4088. ( 10.1128/AEM.00341-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amin M, Porter SL, Soyer OS. 2013. Split histidine kinases enable ultrasensitivity and bistability in two-component signaling networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002949 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002949) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen-Ben-Lulu GN, et al. 2008. The bacterial flagellar switch complex is getting more complex. EMBO J. 27, 1134–1144. ( 10.1038/emboj.2008.48) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2007. In vivo and in vitro analysis of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides chemotaxis signaling complexes. Methods Enzymol. 423, 392–413. ( 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)23018-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferre A, de la Mora J, Ballado T, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2004. Biochemical study of multiple CheY response regulators of the chemotactic pathway of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5172–5177. ( 10.1128/JB.186.15.5172-5177.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abee T, Hellingwerf KJ, Konings WN. 1988. Effects of potassium ions on proton motive force in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 170, 5647–5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metz S, Jager A, Klug G. 2009. In Vivo sensitivity of blue-light-dependent signaling mediated by AppA/PpsR or PrrB/PrrA in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4473–4477. ( 10.1128/JB.00262-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]