Abstract

Background

Despite the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome among young adults, little is known about the awareness level of college students about this condition. The purpose of this study was to assess students’ level of awareness and knowledge about conditions relevant to metabolic syndrome (MetS).

Methods

A self-reported online questionnaire was administered to 243 students attending Central Michigan University. Questions were divided into seven conditions: diabetes, adiposity, hypertension, high serum cholesterol, arteriosclerosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction. Students’ responses were scored and interpreted as follows: poor knowledge if ≤50% of students answered the question correctly; fair knowledge if between 51-80% of students answered the question correctly; and good knowledge if between 81-100% of students answered the question correctly. Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, waist circumference, percentage body fat, and visceral fat score were measured. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the differences in students’ responses. A p value <0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

More than 80% of students correctly identified symptoms and complications of diabetes, hypertension, arteriosclerosis, myocardial infarction and stroke, and 92% identified adiposity as a risk factor for heart disease. There were few false beliefs held by students on questionnaire items. For example, 58% of male students falsely believed that individuals with diabetes may only eat special kinds of sweets compared to 39% of females (p < 0.01) and more than half of the students falsely identified liposuction as the best possible treatment in adiposity therapy. Gender, Health Science major, and year in school were found to be positively associated with more knowledge.

Conclusion

The findings in this study suggest that students’ knowledge about conditions relevant to metabolic syndrome can be improved. In this essence, raising awareness about MetS based on students’ pre-existing knowledge is essential to enhance students’ wellness.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, Cardiovascular risk factors, Adiposity, College students, Lay knowledge

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a constellation of interrelated cardio-metabolic risk factors that include central obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension and dyslipidemia [1–4]. Individuals with MetS are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes [5], cardiovascular disease (CVD) [6, 7], and all-cause mortality [8]. According to the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) report, MetS is identified in individuals when at least three of the following five risk factors are present simultaneously: increased waist circumference, elevated blood pressure, elevated serum triglyceride, reduced HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated fasting plasma glucose [9]. The underlying cause of this syndrome is not yet known, but its manifestation has been linked to obesity (especially abdominal obesity) and insulin resistance [10].

Current literature indicates that MetS is prevalent [11–14] and it is increasing over time [15]. Estimates from the 2003–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that 34% of U.S. adults aged 20 years and over have MetS [13]. This represents a 6% increase in the prevalence of MetS from the 1999–2000 NHANES data [15]. Alarmingly, the prevalence of MetS is common not only among U.S. adults but also among younger persons, and is increasing in parallel with a rise in central obesity [15–17]. According to NHANES, 20.3% of males and 15.5% of females, aged 20–39 years, have MetS [13]. Likewise, MetS prevalence was also documented among college students, in the range of 0.6% to 13% [18–21]. Results from the Young Adult Health Risk Screening Initiative study, conducted among 2722 college students, aged 18–24 years, indicated that 10% of males and 3% of the female participants have MetS [22]. Further, the authors reported that 77% of the males and 54% of the female participants displayed at least one risk factor for MetS (elevated blood pressure in men and low concentrations of HDL-C in women) [22]. Similarly, a study conducted among 300 students at the University of Kansas found that 26% to 40% of the students had at least one metabolic risk factor (low concentrations of HDL-C) [19].This is critical as risk factors for MetS are known to increase the risk of CVD and diabetes later in life. In fact, individuals with MetS appear to have a two-fold increase in risk for CVD and a four-fold increase in risk for type 2 diabetes [22]. Thus, early risk factor detection and intervention is essential to prevent or reduce the development of MetS and, eventually, cardiovascular health problems later in life [23–26].

Universities are unique settings for early risk factor detection and intervention so appropriate lifestyle changes can be implemented at an early age. However, prior to developing any prevention or intervention strategy, assessing the level of awareness and knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS among students is essential. According to the Health Belief Model, risk perception is a primary motive to change a behavior, and the greater the perceived threat, the more likely an individual will change his/her behavior [27, 28]. In this essence, college students should first be aware of MetS and then must perceive themselves at risk so appropriate lifestyle choices can be made. However, a lack of awareness/knowledge might hinder such a change. As such, students who are unaware of MetS or lack knowledge about MetS may not perceive themselves at risk for this condition and, consequently, may go undiagnosed until cardiovascular and diabetes complications occur. Thus, assessing students’ level of awareness and knowledge about conditions relevant to MetS is vital to developing any prevention strategy to reduce MetS.

Currently, there is very little information in the literature about studies examining students’ knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS. Current literature indicates that most college students are unaware of MetS or CVD risk factors and that some students hold false beliefs about CVD complications [29, 30]. Previous reports have indicated that college students do not accurately perceive their own risk factors and rate their own risks lower than their peers’ risk [31]. Thus, the main objective of this study was to assess awareness and knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS among a sample of students from Central Michigan University (CMU). The outcomes of this study may have implications for the design of tailored health promotion programs based on students’ pre-existing knowledge to improve students’ overall health.

Methods

Design and sample

This study was a cross-sectional survey. Out of 270 students recruited, 243 students (174 females and 69 males) completed all the required study assessments, yielding a response rate of 90%. Students were recruited randomly, both in Foods and Nutrition classes and via Blackboard announcements, by a CMU Nutrition and Dietetics professor during fall 2011 and spring 2012 semesters. Students voluntarily entered the study and were provided adequate information about the study protocol. Students agreeing to participate were asked to sign a consent form, in harmony with the Helsinki declaration, and then to come to a laboratory for anthropometric measurements and to receive a numerical code for completing a self-administered online questionnaire. Students were not offered any incentives for their participation. The study protocol was approved by the CMU Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Data collection

Data collection took place in two steps. First, students’ anthropometric measurements including height, weight, waist circumference, percentage body fat, and visceral fat score were measured. Weight, percentage body fat, visceral fat score, and body mass index were determined by Tanita scale body fat analyzer 300A. As fluctuations in body hydration status may affect body composition results, students were instructed to fast and to refrain from any heavy physical activity before Tanita scale measurements were taken in the morning (within 3 hours after waking up). In addition, students were asked to wipe off the bottom of their feet before stepping onto the measuring platform, since unclean foot pads may interfere with conductivity. Height measurements were taken with a stadiometer. Students were asked to take off their shoes for height measurements. Body mass index (BMI) was used to assess students’ weight status [32]. Normal ranges for percentage body fat were considered as follows: 10-20% for males and 20-30% for females based on Tanita score values. In the second step, students were asked to complete a self-administered online questionnaire consisting of questions related to students’ demographics and characteristics, and 90 questions about students’ knowledge about conditions relevant to MetS. The demographic and student characteristics questions were adapted from Yahia et al. [33]. The knowledge questions were adopted from a previous study by Becker et al. [29]. These questions were tested, standardized and validated to be used among university students in a previous study [29]. In addition, the selected adapted questions were administered to a pilot group of 20 students to ensure adequate understanding of the items.

The 90 questions about students’ knowledge were about the conditions often leading to MetS, the outcome and treatment of these conditions, and a description of physical changes relevant to MetS. The questions were divided into seven categories: diabetes (16 questions), adiposity (9 questions), hypertension (12 questions), high serum cholesterol (6 questions), arteriosclerosis (17 questions), stroke (12 questions), and myocardial infarction (18 questions). The response options to the questions were “true”, “false”, or “do not know”. Students’ responses were scored. The “correct” response was awarded one point and the “incorrect” and “do not know” responses were awarded zero points. The maximum possible total score for the MetS questions was 90. Prior to taking the questionnaire, each student was given a numerical code to use. The purpose of coding was to maintain anonymity of the students and to allow them to answer the questions honestly without being identified. The questionnaire was a web-based survey administered via Survey Monkey and was available online for about 10 weeks to accommodate students’ response times.

The definitions for the levels of students’ knowledge were as follows: poor knowledge if ≤50% of students answered the question correctly; fair knowledge if between 51-80% of students answered the question correctly; and good knowledge if between 81-100% of students answered the question correctly [34]. In this study, the questionnaire was pilot-tested on a randomly selected group of 20 students prior to its administration. Students were given instructions on how to fill out the questionnaire completely and truthfully and to skip a question if unsure of the answer.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using the SAS® 9.3 (U.S.A.) software. Descriptive analyses were performed for all study participants. Student’s t-test was used to examine differences in the continuous variables (age, weight, height BMI,% body fat, visceral fat, and waist circumference) between male and female students. Fisher’s exact test or chi-squared was used for the categorical variables (Health-Science vs non-Health Science majors of study, year in school, and presence of family history of various diseases). Fisher’s exact test was also used to examine differences in students’ responses to the questionnaire.

To examine the associations between several variables (such as gender, major of study, year in school, family history, weight status, and ethnicity) and total score for the MetS questions, a Poisson regression model was used. In this model, total score was used as the dependent variable and gender, major of study, family history (any), overweight/obesity, ethnicity, and year in school, were used as independent variables. To assess how these variables were associated with scores on the seven different sections of the questionnaire, seven t-tests were performed to test the differences in the percentage of correct answers for each section (to standardize the unit across the seven sections because the maximum score across the seven sections varied) by the following categorical variables: gender, major, any family history, overweight/obese, ethnicity, and year in school. For all tests, p < 0.05 was used to determine significance; however, since there are multiple tests, this analysis should be considered exploratory. Results were expressed as means ± SD (standard deviation). All reported p values were 2-sided and a p value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A sample of 243 students (72% females and 28% males), with a mean age of 20.6 years, participated in this study. The average weight and height of the participating students were 69.8 ± 16.7 kg and 166.8 ± 9.1 cm, respectively. The mean BMI and percentage body fat for males were 26.1 ± 4.9 kg/m2 and 16.6 ± 8.1, respectively, whereas for females values were 23.4 ± 3.9 kg/m2 and 26.8 ± 6.9, respectively. The mean values of visceral fat scores for males and females were 1.9 ± 1.8 and 3.7 ± 3.4, respectively (Table 1). Of the participating students, 89% were Caucasian, 10% African American, and 1% other ethnicity, reflecting the composition of the ethnic groups at CMU. More than half of the students were Health-Science major (51%) and most of them were in their second and third year of academic study. More women reported a science major (58%) than men (36%). Smoking was not common among students, as 89% of students reported being non-smokers, 6% were current smokers, and 5% were former smokers. Family history of chronic diseases among students was distributed as follows: 13% heart disease, 23% diabetes, 41% hypertension, and 26% cancer. This demographic profile is consistent with national averages in regard to students’ age, gender, and year in school [35], but different in regard to less ethnic diversity, lower percentage of smokers [35], and less obesity [24].

Table 1.

Demographics and student characteristics (Means ± SD)

| Variables | Females | Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | N =174 | N =69 | N =243 |

| Age (Years) | 20.4 ± 1.7* | 21.3 ± 2.4* | 20.6 ± 2.0 |

| Weight (Kg) | 64.1 ± 12.7* | 84.2 ± 17.0* | 69.8 ± 16.7 |

| Height (cm) | 162.9 ± 6.6* | 176.0 ± 6.7* | 166.8 ± 9.1 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 23.4 ± 3.9* | 26.1 ± 4.9* | 24.2 ± 4.4 |

| Body fat (%) | 26.8 ± 6.9* | 16.6 ± 8.1* | 23.9 ± 8.6 |

| Visceral fat score | 1.9 ± 1.8* | 3.7 ± 4.2* | 2.4 ± 2.8 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 81.0 ± 9.7* | 91.2 ± 11.0* | 83.6 ± 11.0 |

| Major of study (%) | |||

| Health science** | 58%* | 36%* | 51% |

| Non-health science | 42%* | 64%* | 49% |

| Year in school (%) | |||

| 1st-year undergraduate | 14% | 15% | 15% |

| 2nd-year undergraduate | 27% | 21% | 25% |

| 3rd-year undergraduate | 27% | 25% | 27% |

| 4th-year undergraduate | 19% | 19% | 19% |

| 5th-year undergraduate | 13% | 19% | 15% |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| White (Hispanic & Non-hispanic) | 91% | 86% | 89% |

| Black (Hispanic & Non-hispanic) | 9% | 10% | 10% |

| Other | 0% | 4% | 1% |

| Family history of chronic disease (%)*** | |||

| Heart Disease | 10%* | 20%* | 13% |

| Diabetes | 23% | 25% | 23% |

| Hypertension | 39% | 41% | 41% |

| Cancer | 12% | 61% | 26% |

| Others**** | 44%* | 21%* | 38% |

| Smoking habit (%) | |||

| Non- smoker | 93%* | 80%* | 89% |

| Current smoker | 3.5% | 12% | 6% |

| Former smoker | 3.5% | 9% | 5% |

*p < 0.05 (between male and female students).

**Health Science majors include: Exercise Science, Health Administration; Health Fitness in Preventive and Rehabilitative Programs, Public Health Education and Health Promotion, School Health Education, Exercise Science, Personal and Community Health, Substance Abuse Education, Prevention, Intervention and Treatment.

***Total% exceeds 100% due to students with a family history of more than one condition.

****Other - includes the “other” family history questions in the data such as family history of overweight, obesity, and high cholesterol.

Metabolic syndrome questionnaire

Overall, results show that students were most knowledgeable about the two conditions: arteriosclerosis and stroke conditions, and least knowledgeable about adiposity and cholesterol. Table 2 shows items where more than 80% of the students answered the questions correctly- indicating good knowledge on questionnaire items; Table 3 shows items where 51-80% of the students answered the questions correctly - indicating fair knowledge; and Table 4 shows items where ≤50% of the students answered the questions correctly- thus indicating poor knowledge or areas for improvement.

Table 2.

Students’ response to the MetS questionnaire by gender - good level of knowledge - (percentage of students answered each question correctly between 81-100%)

| Conditions | Question | Correct answer | Males (N = 69) | Females (N = 171) | Total (N = 240) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Diabetes | There are several different types of diabetes. | True | 62 | 90.0 | 144 | 84.2 | 206 | 85.8 | 0.310 |

| Pregnant women have a reduced risk of acquiring diabetes. | False | 56 | 81.2 | 148 | 86.6 | 204 | 85.0 | 0.320 | |

| Eye disorders can be consequences of diabetes. | True | 60 | 87.0 | 134 | 78.8 | 194 | 81.2 | 0.201 | |

| Adiposity | Adipose individuals have an elevated risk of suffering myocardial infarction. | True | 63 | 91.3 | 15 | 92.9 | 219 | 92.4 | 0.788 |

| Cessation of breathing while sleeping is a possible consequence of adiposity. | True | 52 | 75.4* | 147 | 87.5* | 199 | 84.0 | 0.031 | |

| Adipose individuals are more likely to suffer from arteriosclerosis. | True | 53 | 76.8 | 146 | 86.9 | 199 | 84.0 | 0.078 | |

| Hypertension | Hypertension can cause dizziness. | True | 60 | 88.2 | 144 | 85.2 | 214 | 86.1 | 0.679 |

| High serum cholesterol | A low cholesterol diet can supplement therapy for high serum cholesterol. | True | 62 | 89.9 | 148 | 89.2 | 210 | 89.4 | 1.000 |

| High serum cholesterol can be treated with medication. | True | 58 | 84.1 | 142 | 85.5 | 200 | 85.1 | 0.841 | |

| High serum cholesterol promotes arteriosclerosis. | True | 53 | 76.8* | 145 | 87.9* | 198 | 84.3 | 0.046 | |

| Arteriosclerosis | Arteriosclerosis increases the risk of suffering a stroke. | True | 59 | 85.1* | 162 | 96.4* | 221 | 93.3 | 0.007 |

| Leg pains are a symptom of arteriosclerosis. | True | 56 | 81.2 | 148 | 88.1 | 204 | 86.1 | 0.214 | |

| In arteriosclerosis, a sustainer can be inserted into the artery in order to stabilize it. | True | 56 | 81.2* | 151 | 91.0* | 207 | 88.1 | 0.041 | |

| Individuals with high blood pressure are more likely to suffer from arteriosclerosis. | True | 50 | 72.5* | 148 | 89.2* | 198 | 83.9 | 0.003 | |

| Stroke | A stroke affects the brain. | True | 61 | 88.4* | 162 | 97.0* | 223 | 94.5 | 0.023 |

| If a patient survives a stroke, there are usually no permanent consequences. | False | 52 | 75.4* | 146 | 88.0* | 198 | 84.3 | 0.011 | |

| Permanent speech defects are possible consequences of a stroke. | True | 59 | 85.5* | 159 | 95.1* | 218 | 92.4 | 0.015 | |

| A stroke is often followed by memory dysfunction. | True | 52 | 75.4* | 150 | 89.8* | 202 | 85.6 | 0.007 | |

| There are different types of strokes. | True | 54 | 78.3* | 151 | 90.4* | 205 | 86.9 | 0.018 | |

| A stroke is preceded frequently by speech problems. | True | 58 | 84.1 | 146 | 88.0 | 204 | 86.4 | 0.407 | |

| Myocardial infarction | When suffering a myocardial infarction, pain may radiate into the arms. | True | 58 | 85.3 | 155 | 93.4 | 213 | 91.0 | 0.075 |

| Hereditary factors play a role in the risk of suffering a myocardial infarction. | True | 51 | 75.0 | 138 | 83.6 | 189 | 81.1 | 0.142 | |

| After a myocardial infarction, anticoagulants are administered. | True | 60 | 88.2 | 148 | 89.2 | 208 | 88.9 | 0.822 | |

| A myocardial infarction is often preceded by shortness of breath. | True | 54 | 79.4* | 153 | 92.2* | 207 | 88.5 | 0.012 | |

| A myocardial infarction is caused by arterial obstruction. | True | 53 | 77.9 | 146 | 88.0 | 199 | 85.0 | 0.068 | |

| After a myocardial infarction has occurred, parts of the cardiac muscle tissue can die. | True | 64 | 92.6 | 158 | 95.8 | 222 | 94.9 | 0.344 | |

| With a myocardial infarction, cardiac muscle tissue dies. | True | 51 | 75.0 | 141 | 84.9 | 192 | 82.1 | 0.091 | |

*p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Students’ response to the MetS questionnaire by gender – fair level of knowledge – (percentage of students answered correctly between 51-81%)

| Conditions | Question | Correct answer | Males (N = 69) | Females (N = 171) | Total (N = 240) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Diabetes | Hereditary factors play a major role in the development of diabetes. | True | 54 | 78.3 | 138 | 80.7 | 192 | 80.0 | 0.722 |

| An increased alertness is a frequent symptom of diabetes. | False | 47 | 68.2 | 141 | 82.5 | 188 | 78.3 | 0.310 | |

| Hereditary factors play only a minor role in the development of diabetes. | False | 43 | 62.3 | 112 | 65.5 | 155 | 64.6 | 0.657 | |

| For some individuals with diabetes it is not advisable to take insulin. | True | 57 | 82.6 | 119 | 69.6 | 176 | 73.3 | 0.052 | |

| Individuals with diabetes may only eat special kinds of sweets for diabetes. | False | 29 | 42.0* | 104 | 60.8* | 133 | 55.4 | 0.010 | |

| With diabetes, sugar cannot enter the cells sufficiently. | True | 47 | 69.1 | 103 | 60.6 | 150 | 63.0 | 0.237 | |

| Poor appetite is a frequent symptom of diabetes. | False | 33 | 47.4 | 93 | 54.4 | 126 | 52.5 | 0.393 | |

| With diabetes, too much sugar enters the cells. | False | 45 | 65.2 | 89 | 52.1 | 134 | 55.8 | 0.084 | |

| Pregnant women have an increased risk of acquiring diabetes. | True | 47 | 69.1 | 134 | 78.4 | 181 | 75.7 | 0.136 | |

| Frequent urination is a classic symptom of diabetes. | True | 55 | 79.7 | 121 | 71.2 | 176 | 73.6 | 0.198 | |

| Arteriosclerosis is one of the sequalae of diabetes. | True | 44 | 63.8 | 109 | 64.1 | 153 | 64.0 | 1.000 | |

| Adiposity | An excessively fatty, high-caloric is the only factor that determines adiposity. | False | 43 | 62.3 | 105 | 62.5 | 148 | 62.5 | 1.000 |

| Adipose individuals have the same risk than non-adipose individuals of suffering a stroke. | False | 45 | 65.2 | 120 | 71.4 | 165 | 69.2 | 0.355 | |

| Adiposity can be treated surgically. | True | 45 | 65.2 | 128 | 76.2 | 173 | 73.0 | 0.107 | |

| Hypertension | Hypertension is associated with heredity. | True | 54 | 79.4 | 138 | 80.7 | 192 | 80.3 | 0.858 |

| For the most part, a concrete single reason of why a patient suffers from hypertension can be determined. | False | 33 | 48.5 | 103 | 60.2 | 136 | 56.9 | 0.067 | |

| Pregnant women are less likely to suffer from hypertension. | False | 48 | 70.6* | 143 | 83.6* | 191 | 79.9 | 0.031 | |

| After medication has lowered hypertension, the medication can usually be discontinued. | False | 44 | 64.7 | 115 | 67.7 | 159 | 66.8 | 0.761 | |

| Individuals with hypertension are less likely to suffer from arteriosclerosis. | False | 44 | 64.7* | 134 | 78.8* | 178 | 74.8 | 0.031 | |

| Hypertension can be caused by disorders of the thyroid gland. | True | 54 | 79.4 | 133 | 78.4 | 187 | 78.6 | 1.000 | |

| Hypertension can cause renal damage. | True | 53 | 77.9 | 134 | 78.8 | 187 | 78.6 | 0.863 | |

| Hypertension can lead to eye disorders. | True | 49 | 72.1 | 119 | 70.0 | 168 | 70.6 | 0.875 | |

| Hypertension can be caused by cerebral tumors. | True | 43 | 63.4 | 111 | 65.3 | 154 | 64.7 | 0.766 | |

| High serum cholesterol | High serum cholesterol is not associated with hereditary factors. | False | 46 | 66.7* | 133 | 80.6* | 179 | 76.2 | 0.028 |

| Arteriosclerosis | With arteriosclerosis, arteries become softer. | False | 42 | 60.8 | 109 | 64.9 | 151 | 63.7 | 0.556 |

| Arteriosclerosis can be cured completely. | False | 48 | 69.6 | 135 | 80.4 | 183 | 77.2 | 0.088 | |

| With arteriosclerosis, arteries become less elastic. | True | 45 | 65.2* | 141 | 83.9* | 186 | 78.5 | 0.003 | |

| As a result of arteriosclerosis, blood pressure is likely to decline. | False | 42 | 60.9* | 129 | 76.8* | 171 | 72.2 | 0.017 | |

| As a result of arteriosclerosis, blood pressure is likely to increase. | True | 53 | 76.8 | 136 | 81.0 | 189 | 79.8 | 0.480 | |

| High blood pressure and arteriosclerosis are not linked with each other. | False | 51 | 73.9 | 135 | 81.3 | 186 | 79.2 | 0.212 | |

| The risk of suffering from arteriosclerosis is not hereditary. | False | 41 | 59.4* | 125 | 74.9* | 166 | 70.3 | 0.028 | |

| Arteriosclerosis can cause renal damage. | True | 53 | 76.8 | 124 | 74.7 | 177 | 75.4 | 0.869 | |

| With arteriosclerosis, blood platelets accumulate on the arterial walls. | True | 54 | 78.3 | 117 | 70.5 | 171 | 72.8 | 0.261 | |

| With arteriosclerosis, fat accumulates on the arterial walls. | True | 45 | 75.2* | 133 | 79.6* | 178 | 75.4 | 0.030 | |

| Medication can remove completely sediments from the arteries. | False | 45 | 65.2 | 118 | 71.1 | 163 | 69.4 | 0.438 | |

| With arteriosclerosis, arteries become brittle. | True | 50 | 72.5 | 109 | 65.3 | 159 | 67.4 | 0.351 | |

| A stroke is caused by artery obstruction. | True | 51 | 73.9 | 139 | 83.2 | 190 | 80.5 | 0.107 | |

| The nutrient supply to the brain is not affected by a stroke. | False | 44 | 63.8* | 142 | 85.5* | 186 | 79.2 | <0.001 | |

| A stroke is characterized by a sudden dysfunction of the heart. | False | 44 | 63.8 | 89 | 53.3 | 133 | 56.4 | 0.151 | |

| A stroke is caused when overexcited cells produce too much electricity. | False | 44 | 63.8 | 103 | 61.7 | 147 | 62.9 | 0.883 | |

| Individuals with diabetes are more likely to suffer a stroke. | True | 47 | 68.2 | 122 | 73.1 | 169 | 69.1 | 0.526 | |

| Smoking is a minor risk factor with respect to a myocardial infarction. | False | 35 | 51.5* | 109 | 66.1* | 144 | 61.8 | 0.031 | |

| The oxygen supply to the heart is not affected by a myocardial infarction. | False | 45 | 66.2* | 138 | 83.1* | 183 | 78.2 | 0.008 | |

| Damage caused by a myocardial infarction is not usually permanent. | False | 45 | 66.2* | 133 | 80.6* | 178 | 76.4 | 0.027 | |

| Diabetes is a predisposing factor for a myocardial infarction. | True | 42 | 60.9 | 122 | 73.5 | 164 | 69.8 | 0.062 | |

| When suffering a myocardial infarction, pain may radiate into the stomach. | True | 38 | 55.1 | 105 | 63.3 | 143 | 60.9 | 0.245 | |

| A myocardial infarction can manifest itself through nausea and vomiting. | True | 42 | 60.9 | 94 | 56.6 | 136 | 57.9 | 0.565 | |

*p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Students’ response to the MetS questionnaire by gender - poor level of knowledge – (percentage of students answered correctly ≤50%)

| Conditions | Question | Correct answer | Males (N = 69) | Females (N = 171) | Total (N = 240) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Diabetes | Individuals with diabetes must have insulin shots. | False | 30 | 43.5 | 76 | 44.7 | 106 | 44.4 | 0.887 |

| With diabetes, sugar cannot move in the blood. | False | 25 | 36.2 | 56 | 32.8 | 81 | 33.8 | 0.652 | |

| Adiposity | The terms ‘overweight’ and ‘adiposity’ are synonyms. | False | 35 | 50.7 | 70 | 41.7 | 105 | 44.3 | 0.250 |

| Liposuction is the best possible treatment in adiposity therapy. | False | 27 | 39.1 | 75 | 44.6 | 102 | 43.0 | 0.472 | |

| Hypertension | People with hypertension are as likely to suffer from arteriosclerosis as those with normal hypertension. | False | 32 | 47.1 | 67 | 39.2 | 99 | 41.4 | 0.309 |

| Pregnant women are as likely to suffer from hypertension as non-pregnant women. | False | 31 | 45.6 | 76 | 44.7 | 107 | 45.0 | 1.000 | |

| High serum holesterol | High serum cholesterol does not cause acute ailments. | True | 24 | 34.8* | 26 | 15.7* | 50 | 21.3 | 0.002 |

| Fatigue is a frequent symptom of high serum cholesterol. | False | 16 | 29.2 | 30 | 18.1 | 46 | 19.6 | 0.372 | |

| Arteriosclerosis | With arteriosclerosis, arteries contract. | False | 21 | 30.3 | 43 | 25.6 | 64 | 27.0 | 0.511 |

| Stroke | A stroke is preceded frequently by chest pains. | False | 32 | 46.4 | 80 | 47.9 | 112 | 47.5 | 0.886 |

| Myocardial infarction | A myocardial infarction is caused by cerebral dysregulation of the heart. | False | 32 | 47.1* | 47 | 28.3* | 79 | 33.8 | 0.009 |

| A myocardial infarction must be treated surgically. | False | 25 | 36.3 | 60 | 36.1 | 85 | 36.2 | 1.000 | |

| A myocardial infarction is typically followed by some degree of paralysis. | False | 23 | 33.3 | 78 | 47.0 | 101 | 43.0 | 0.061 | |

| A myocardial infarction is caused by malfunction of one or more heart valves. | False | 14 | 20.3 | 24 | 14.6 | 38 | 16.2 | 0.331 | |

| A myocardial infarction is usually preceded by loss of sensation and numbness. | False | 20 | 29.0 | 33 | 19.9 | 53 | 22.6 | 0.161 | |

*p < 0.05.

Good level of knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS

Students indicated good knowledge on various questionnaire items about conditions relevant to MetS. As shown in Table 2, more than 80% of students were aware about diabetes types, eye complications, and increased risk in pregnancy. Ninety two percent of the students identified adiposity as a risk factor for heart disease and 84% knew that adiposity, and high serum cholesterol, can predispose individuals to arteriosclerosis. Likewise, more than 85% of students knew that individuals with hypertension may complain of dizziness and that high serum cholesterol can be treated with diet and medications.

Arteriosclerosis was clear to many students in regard to disease characteristics, symptoms, and risk factors. For example, 86% of the students correctly identified leg pain as a symptom of arteriosclerosis, 93% (85.5% of males and 96% of females) knew that arteriosclerosis increases the risk of suffering a stroke (p < 0.05), and 88% knew that a stent can be surgically inserted into an arteriosclerotic artery to increase the flow of blood through it.

As for the stroke questions, most students indicated good knowledge about causes, symptoms and complications of stroke with few statistically significant differences between genders. For example, 94.5% of the students knew that stroke affects the brain, but more females (97%) than males (88%) responded correctly to this question (p < 0.05). Also, 95% of the female students knew that a permanent speech defect is a potential consequence of stroke compared to 85.5% of the males (p < 0.05). Likewise, 89% of the females knew that a stroke is often followed by a memory dysfunction compared to 75% of males (p < 0.05) and 86.4% of the students were aware that a stroke is usually preceded by speech problems.

Students indicated good knowledge about myocardial infarction in terms of causes, symptoms and treatment with few gender differences. For example, 85% of students knew that obstructive coronary artery disease may cause myocardial infarction and 91% of students knew that most myocardial infarctions can cause chest pain radiating into the right or left arm. More females (92%) than males (79%) knew that shortness of breath may precede a myocardial infarction (p < 0.05) which may lead to permanent damage of the affected heart tissue (85% of females vs. 75% of males), and 89% of the students were aware that anticoagulant medications are administered after a myocardial infarction.

Fair level of knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS

Table 3 shows the questions where students’ correct answers were between (51-80%) indicating fair knowledge. Students showed fair knowledge about diabetes in regard to risk factors, symptoms, diet and complications. About 80% of students knew that hereditary factors can play a role in the development of diabetes. Polyuria was identified by 74% of students as a common symptom of diabetes and 64% identified arteriosclerosis as one of the sequela of diabetes. However, 45% of the students (58% of males and 39% of females) falsely believed that patients with diabetes can only eat special kinds of sweets (p < 0.05).

Adiposity was fairly understood by students in regard to risk factors and treatment. About 69% of students were aware that obesity increases the chance of suffering a stroke and 73% knew that adiposity can be treated surgically. As for hypertension, students indicated fair knowledge in terms of risk factors, causes, and treatment. About 80% of students were aware that hereditary factors can contribute to hypertension. However, 43% of students falsely believed that most cases of hypertension can be attributed to a single, easily identified cause, and 33% assumed that antihypertensive medications could be discontinued once blood pressure was under control. Complications of untreated hypertension, such as kidney and eye diseases, were identified by 70% of students.

Poor level of knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS

Table 4 shows the questions where less than 50% of students answered the questions correctly, thus indicating poor knowledge or areas for improvement. Students showed poor knowledge about some aspects of the physiology and treatment of diabetes. About 66% of the students assumed that sugar cannot “move” in the blood with diabetes and 56% thought that all patients with diabetes must take insulin injections. In regard to adiposity, 56% of students thought that the terms “overweight” and “adiposity” were synonymous and 57% of students falsely believed that liposuction was the best possible treatment for adiposity.

In terms of hypertension, only 45% of students knew that pregnant women were more likely to suffer from hypertension than non-pregnant women. Consequences of high serum cholesterol were not clear to students as 79% thought that high serum cholesterol causes acute ailments and 80% of students falsely believed that fatigue could be a frequent symptom of high serum cholesterol. There were few false beliefs among students about arteriosclerosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction. For example, 73% of students falsely believed that with arteriosclerosis, arteries contract and 52.5% of the students falsely believed that a stroke is preceded by chest pain.

Myocardial infarction was not clear to students in terms of causes, symptoms, and treatment. About 66% of students falsely believed that a myocardial infarction is caused by cerebral dysregulation of the heart, 84% thought that myocardial infarction is caused by malfunction of one or more heart valves, 77.5% assumed that myocardial infarction is preceded by a loss of sensation and numbness, 57% believed that myocardial infarction is typically followed by some degree of paralysis. More than two-thirds of the students (64%) thought that myocardial infarction must be treated surgically.

Total score in relation to gender, major of study, year in school, family history, BMI, and ethnicity

Results of the Poisson Regression model regressing total score on gender, major of study, any family history, overweight/obese, ethnicity, and year in school as covariates, indicated that gender, major of study and year in school were significant factors associating with differences in total score. Controlling for covariates mentioned, females scored 6% higher than male students (p = 0.01), Health Science major students scored 7% higher (p = 0.0011) than non- Health Science major students. Compared to 1st year students, 5th year had 11% higher scores (p = 0.002). Family history of disease, BMI and ethnicity were not significantly associated with total score (Table 5). Table 6 shows the average percent correct answers per condition, which ranged from 62.7% (lowest percentage on adiposity questions) to 77.3% (highest percentage on stroke questions).

Table 5.

Poisson Regression Model - Total Score*

| Total score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR* | P Value |

| Gender (Female) | 1.06 | 0.010 |

| Health sciences major | 1.07 | 0.001 |

| No family history | 0.97 | 0.106 |

| BMI <25 | 0.99 | 0.530 |

| Ethnicity (White) | 1.05 | 0.111 |

| 2nd year | 0.98 | 0.557 |

| 3rd year | 1.00 | 0.927 |

| 4th year | 1.06 | 0.059 |

| 5th year | 1.11 | 0.002 |

*overall model p < 0.001.

*OR (odd ratio).

Table 6.

Summary of Average Scores and Percentage of Correct Answers Per Condition as Questionnaire Topic Areas (N = 243)

| Condition | Maximum score | Average score | SD* | Average percentage of correct answers | SD* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 16 | 10.7 | 2.5 | 66.6 | 15.9 |

| Adiposity | 9 | 5.7 | 1.6 | 62.7 | 17.4 |

| Hypertension | 12 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 68.8 | 20.2 |

| Cholesterol | 6 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 62.7 | 18.5 |

| Arteriosclerosis | 17 | 12.6 | 3.2 | 74.1 | 18.7 |

| Myocardial infarction | 18 | 11.7 | 3.0 | 64.8 | 16.8 |

| Stroke | 12 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 77.3 | 21.5 |

* Standard deviation.

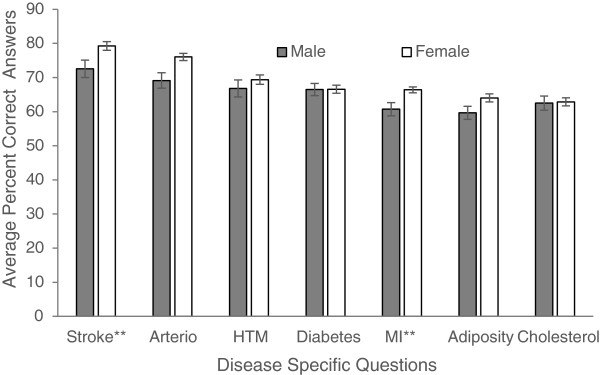

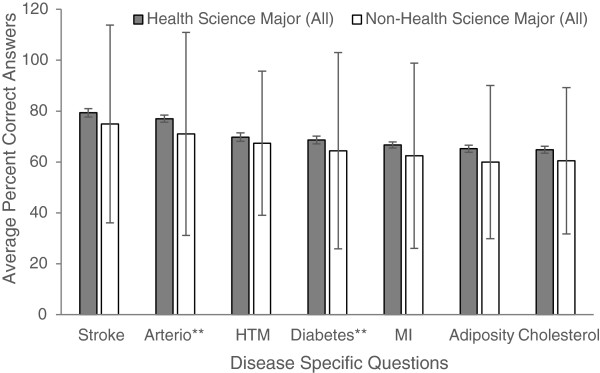

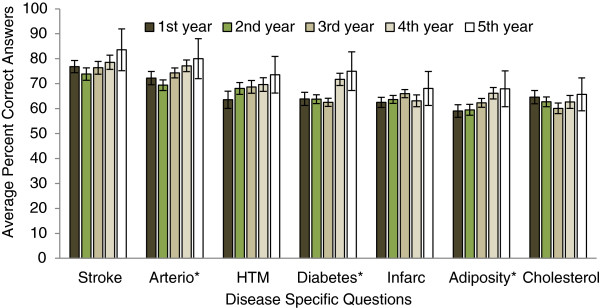

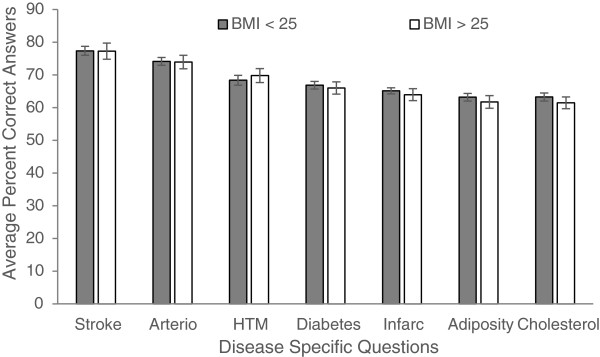

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 explore visually the trends for average percent correct answers per condition for various characteristics. Females scored higher than males on most conditions, except for “Diabetes” and “Cholesterol” sections, where males had similar average score as females (Figure 1). Health Science major students consistently scored higher than non-Health Science major students (Figure 2). Those students in the 5th-year of study scored higher than those students in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th- years; however, there was an overlap between the other grade years (Figure 3). While those students with family history of some diseases generally scored higher than those students with no-family history, this difference was not statistically significant for most of the tests (Figure 4). There was no difference between the knowledge of healthy weight students and that of obese or overweight students (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Students’ knowledge based on gender.

Figure 2.

Students’ knowledge based on major of study.

Figure 3.

Students’ knowledge based on year in school.

Figure 4.

Students’ knowledge based on family history.

Figure 5.

Students’ knowledge based on weight status (healthy weight vs. overweight/obese).

Discussion

Study’s results show that students were most knowledgeable about arteriosclerosis and stroke conditions and least knowledgeable about adiposity and cholesterol. There were some false beliefs held by students. For example, 56% of the students falsely believed that all individuals with diabetes must take insulin injections, 55.4% falsely believed that individuals with diabetes can only eat special kinds of sweets, and 57% falsely identified liposuction as the best possible treatment for adiposity. There was no pattern for significant gaps in knowledge between the conditions or type of knowledge missing. The average percentage correct answers by condition varied from 62.7% to 77.3%. Similar analyses by type of information (enabling conditions often leading to, description of physical changes, outcomes of condition and treatment of the conditions) did not reveal any consistent gaps in knowledge. Therefore, the discussion of areas for improvement will be explored by the individual questions. As expected, Health-Science major students scored 7% higher than non-Health-Science major students (p < 0.001), and 5th- year students scored 11% higher than 1st-year students (p < 0.001). Students majoring in Health Sciences would have covered these topics more intensely than students of non-Health Science majors. Also, students in their 5th-year would be expected to perform better than 1st-year students as they are in their final year of schooling and would have covered more coursework on the topic. In regards to gender, female students showed better “understanding” since being female was associated with a 6% higher score after controlling for the other covariates in the regression model (p < 0.01). Female students scored higher than male students on most questionnaire sections, except for “Diabetes” and “Cholesterol” sections, where scores were similar for both genders. It could be argued that the gender differences seen in this study were due to the field of study as more females (58%), than males (36%), were majoring in Sciences; however, based on the Poisson Regression analysis, after controlling for covariates (major of study, year in school, BMI, ethnicity), females still scored higher than male students (p < 0.01). One possible explanation for this difference in results might be that female students are more concerned about their body shape and may have more interest in health issues than male students at college age [36]. Male students, in general, have more interest in extracurricular activities than in health issues. Results also indicated that students with family history of some diseases generally scored higher than students with no family history, but differences were not statistically significant. To test whether students’ specific family history was associated with knowledge by score condition, (for example if students had a family history of diabetes, were their diabetes scores higher), regression analysis did not indicate any significant differences.

Nevertheless, in spite of the majority of students correctly identified symptoms and complications of diabetes, adiposity, hypertension, arteriosclerosis, myocardial infarction and stroke, there were some misconceptions held by students on questionnaire items that have implications for future health education efforts and whether students will be prompted to make personal healthy lifestyle choices. For example, in terms of diabetes, about half of the students believed that individuals with diabetes can only eat special kinds of sweets and more than two-thirds of the students thought that sugar cannot “move” in the blood in patients with diabetes. These results reflect a lack of understanding about the etiology and treatment of diabetes. The notion that individuals with diabetes cannot eat sweets or desserts like anyone else may also reflect the general public’s notions about diabetes. Diabetes is a serious health problem and it is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States [37]. Thus, educating students about this disease as a first step in awareness and knowledge is important as a precursor to other health education efforts that could lead to actual behavior changes to reduce their personal risk of developing diabetes or metabolic syndrome later in life.

Central obesity is a leading risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Results indicated that the majority of students, irrespective of weight, were aware that adiposity is a risk factor for heart disease, stroke and arteriosclerosis. However, students were not clear about whether the terms “overweight” and “adiposity” are synonyms. These terms are often misleading and sometimes used as synonyms, even though the former refers to the gaining of body weight, and the latter refers to an excess of body fat. Also, adiposity treatment was not clear to students as more than half of the students thought that liposuction is the best possible treatment in adiposity therapy. This finding may be related to how the media portray liposuction as a revolutionary treatment for adiposity therapy. It was reported that most college students acquire their health information via television, popular magazines, and the internet rather than from credible, evidence-based information sources [38]. Confusion about overweight and adiposity and the notion that liposuction is the best possible obesity treatment may contribute to students failing to understand that the amount and placement of adipose tissue in the body are more important concepts than body weight itself. While the survey did not specifically measure knowledge related to body fat distribution, e.g. central obesity, lack of clarity about adiposity may further confuse the issue. The belief that liposuction is the best possible obesity treatment, may lead to students overlooking the importance of making healthy lifestyle choices, including healthy eating habits and regular physical activity, as the primary prevention and treatment options. Also, this could lead students to the perception that healthy lifestyles are not necessarily important since other actions can be taken later to resolve the health consequences.

In this study, findings related to the hypertension questions indicated that the majority of students knew that hypertension can be manifested as dizziness, is linked to the genetic makeup of an individual, and heredity is a risk factor for this condition. However, when students were asked whether pregnant women are as likely to suffer from hypertension as non-pregnant women, only 45% of the female students responded correctly to this question. In addition, only 41.4% of the students knew that there is a relationship between hypertension and arteriosclerosis. Hypertension is often called a “silent” killer because it usually starts with no symptoms or warning signs and progress before individuals realize that they have it. It has been estimated that about 1 in 5 (20.4%) adults in the U.S. have high blood pressure but are unaware of it [39–42]. In this regard, students’ correct response identifying that dizziness is a symptom of blood pressure may lead them to a false sense of safety if they wait for this sign and symptom, prior to seeking health advice or making healthy lifestyle choices, to prevent the development of hypertension. Students’ response also indicates a lack of understanding about risk for hypertension during pregnancy and the connection between hypertension and arteriosclerosis.

In regard to the cholesterol questions, results are encouraging as more than two-thirds of the students were aware that family history is a risk factor for high serum cholesterol, and more than 85% of the students were aware that high serum cholesterol can be treated with diet and medication. In 2008 in Germany, Becker et al. reported that only about half of their participating students knew that heredity and serum cholesterol were related, and that high serum cholesterol can promote arteriosclerosis [29]. The differences seen in students’ responses in our study and that of Becker et al. might be due to the cultural differences in risk perceptions. It might be that our students are more familiar with cholesterol as a risk factor for heart disease than students in the Becker et al. study [29] since heart disease is the number one killer in the U.S. [6].

As for arteriosclerosis questions, 93% of students were aware that arteriosclerosis can increase the risk of suffering a stroke, but more than two-thirds of the students were not aware that elevated cholesterol can thicken the wall of the arteries leading to stiffness and loss of elasticity, and only 20% knew that high cholesterol did not cause “acute” ailments and that fatigue was not a symptom of elevated cholesterol. Therefore, it is unclear that the ultimate connection between elevated serum cholesterol, arteriosclerosis, and stroke is fully understood by students. Morrell et al. conducted a study among 360 undergraduate students recruited from three universities in the U.S. and reported that 12% of their male participants had MetS compared to 6% of their female participants [22]. In general, men do not routinely seek medical care and discuss health complications with their healthcare providers, and in this study also male students showed lower knowledge about these conditions [43]. This suggests that there is a need to increase knowledge of the interconnections between elevated cholesterol and CVD complications among students, especially male students. This lends support for campaigns such as “know your number” [44] as an effective way to raise awareness among male students about the need to have their serum cholesterol measured and for each student to know his results in order to spur the necessary lifestyle changes, if needed.

As for myocardial infarction and stroke questions, there seems to be confusion between myocardial infarction and stroke as almost half of the students believed that a stroke was frequently preceded by chest pain and is characterized by a sudden dysfunction of the heart. More than two-thirds of the students falsely thought that myocardial infarction is caused by cerebral dysregulation of the heart, and 84% believed that myocardial infarction is caused by malfunction of the heart valves. Similar findings were reported by other authors. Becker et al. [29] reported that more than one-third of their participating students thought that a stroke often begins as chest pain and about 70% believed that myocardial infarction was due to malfunctioning of the heart valves [29]. However, symptoms of myocardial infarction were better understood by students as the majority of students, especially females, knew that most myocardial infarctions can cause chest pain that can radiate into the right or left arm, shortness of breath, and can permanently damage the heart tissue. However, over 70% of the students falsely believed that a myocardial infarction was usually preceded by a loss of sensation and numbness, more than half of the students inaccurately believed that surgical treatment was needed, and that paralysis was an outcome of myocardial infarction. Munoz et al. [38] also reported that a high proportion of their female students knew the causes of heart disease and were aware of the basic warning signs associated with a heart attack [38].

Whether specific knowledge about the individual conditions and signs and symptoms is critical to students to recognizing their personal risk and making the behavior and lifestyle changes at an early age that are necessary to prevent these conditions is still unknown. However the results of this study indicate that there are opportunities for clarifying understanding about specific conditions. In particular, health education may need to be developed that targets students of non-Health Science majors since their knowledge is different than Health Science majors. The level of understanding is only significantly different for those students in the 5th year of school. Educating students about cardiovascular diseases and stroke at early stages is very important; especially risk factors for heart disease that are established at an early age [45].

As indicated previously, the impact of a Science-based curriculum on health knowledge is confirmed as expected by these study results and this increased knowledge cannot be attributed to the higher proportion of females, versus males, that reported a Science field of study. As students become more educated about MetS risk factors, positive lifestyle changes are more likely to be followed. Colleges and universities should put their emphasis not only on students’ mainstream coursework but also on students’ health education that involve preventive strategies to promote good health and minimize the development of MetS risk factors among students at an early age. It has been documented that lifestyle modifications are an effective treatment strategy to reduce MetS [46–51]. In this essence, mandating the incorporation of health education courses into the curriculum should be a priority for colleges and universities to enhance students’ wellness and promote a healthy lifestyle that nurtures students’ academic success - in particular for non-Health Science majors since they have the lowest level of knowledge.

Study’s strengths and limitations

Given the serious health problems resulting from MetS, evaluating students’ level of awareness and knowledge about conditions relevant to MetS is crucial. Colleges and universities are often the final academic settings where students can acquire knowledge about health-related issues and develop positive lifestyle skills. Findings from this study will help in filling the gap in evaluating students’ knowledge about conditions relevant to MetS and in identifying students’ existing false beliefs. Critical baseline information was provided in this study and results can be used in developing health education courses tailored to students’ needs. The main limitation of this study is the small sample size, which limits the generalization of this study’s findings and limits the statistical power to detect significant differences between genders. Therefore, this study’s results should be interpreted with caution, as results may not be generalizable to all university students. Another limitation is the use of the cross-sectional design which cannot distinguish whether the false belief is a result of students’ lack of awareness or due to students’ pre-existing knowledge. Also, this study was limited in that most of the participants were female students (72% female vs. 28% male). Female students may have been more interested in research related to health issues than male students, since participants voluntarily entered into the study. Nevertheless, the dominance of female participants reflects the university’s student body data and is consistent with the gender composition of a large-scale national study [35]. The participants’ answers were self-reported; thus, factors such as question interpretation and understanding by students may have also affected the results. Lastly, it would be important to replicate this study in schools having a more ethnically diverse student population than in the current study and to include students pursuing a greater variety of majors. Given the serious implications of MetS on health, research on this topic deserves further attention.

Conclusions

The present study provides insight into students’ knowledge about conditions relevant to MetS.

Students’ understanding of conditions relevant to metabolic syndrome differed among domains, with few gender differences and few false beliefs. Knowledge about a health condition’s signs and symptoms, health consequences, and treatment are prerequisites to the next component of the health belief model—understanding “your” personal risk. While the students acknowledged the importance of heredity, this may still not translate into personal risk for them at the level necessary for them to consider behavior change and adoption of more healthy lifestyles. In this study, specific family history did not impact students’ knowledge in those specific conditions. Thus, using family history as a perceived threat (according to Health Belief Model) to motivate students may not be effective. This research indicates that health education programs at the college level may be able to assume basic knowledge about the various conditions related to MetS; however, there is a room for improvement. Also, colleges may need to focus on the how these conditions relate to the students on a personal level, so that this knowledge is more likely to lead to healthy lifestyles. A recent study conducted by Hawkins et al. indicated that knowledge acquisition via education is effective when education is tailored to students’ needs [52]. Other researchers also noted that acquiring knowledge about health-related problems was associated with more positive changes [53, 54]. In this essence, health education based on individual’s “personal” risk is important to facilitate voluntary adaptions of healthy behavioral choices.

Given the increasing prevalence of MetS among college-aged adults, raising awareness about MetS among this age group is important to reduce the prevalence of this condition. Colleges and universities are ideal settings to educate students about health issues, however, they need to move beyond simple knowledge acquisition and focus on the ability to connect this knowledge on a “personal” level to the individual student’s perception of their own risk and then equip them with the right skills needed to help them translate knowledge into positive lifestyle behaviors. Previous studies have indicated that lifestyle interventions, including a healthy eating pattern, regular physical activity, and weight management, can substantially reduce the prevalence of MetS among various age groups of different populations [42–46]. Future research should examine whether students’ knowledge of conditions relevant to MetS did translate into their lifestyle practices towards Mets risk reduction. This question can be investigated by assessing the actual prevalence of MetS among CMU students. Future research should also explore the strategies that can stimulate students’ personal risk perception to create positive change in their lifestyle behaviors.

Acknowledgments

A special note of appreciation goes to Dr. Esther Myers for her constructive and invaluable comments on the draft. Also, I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to CMU students, namely Joshua Bolender, Ethan Michaels, Alyssa Thornton, Ashley Harper, Courtnay Hughes, Elizabeth Kasbow, Kaitlin Thomas, and Melissa Harmon for assisting in literature review, data entry, references’ listing, and to all CMU students who participated in this study. In addition, a thank you note goes to Tanita Corporation for providing the body fat analyzer 300A scale for this research.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the EHS Scholarship grant and the Faculty Research and Creative Endeavors (FRCE) Premier Display grant at CMU.

Abbreviations

- MetS

Metabolic Syndrome

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- HDL-C

High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol, BMI, Body Mass Index.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NY carried out questionnaire design, manuscript preparation, data collection and study coordination. CB contributed in the statistical analysis. MR contributed in data collection and data entry. MC performed all the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Najat Yahia, Email: yahia1n@cmich.edu.

Carrie Brown, Email: Carrie.Brown@tufts.edu.

Melyssa Rapley, Email: melyssarapley@gmail.com.

Mei Chung, Email: Mei_Chun.Chung@tufts.edu.

References

- 1.Reaven GM. The metabolic syndrome: is this diagnosis necessary? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1237–1247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, Niskanen LK, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Lakka TA. Metabolic syndrome and development of diabetes mellitus: application and validation of recently suggested definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(11):1070–1077. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, Vasan RS, Nathan DM, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):2906–2912. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsén B, Lahti K, Nissén M, Taskinen MR, Groop L. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(4):683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119(10):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik S, Wong ND, Franklin SS, Kamath TV, L'Italien GJ, Pio JR, Williams GR. Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1245–1250. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140677.20606.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel Evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37(13):1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Nat Hlth Stat Rep. 2009;13(5):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: findings from The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287(3):356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2444–2449. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrell JS, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Quick V, Olfert M, Dent A, Carey GB. Metabolic syndrome: Comparison of prevalence in young adults at 3 Land-Grant universities. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.841703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diab Care. 2011;34(1):216–219. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1519–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes and obesity related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang TT, Kempf AM, Strother ML, Chaoyang L, Lee RE, Harris KJ. Overweight and components of the metabolic syndrome in college students. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):3000–3001. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang TT, Shimel A, Lee RE, Delancey W, Strother ML. Metabolic risks among college students: prevalence and gender differences. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 2007;5(4):365–372. doi: 10.1089/met.2007.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen SL, Chiu TY, Lin YC, Lee YC, Lee L, Huang KC. Obesity and hepatitis B infection are associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome in university freshmen. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(3):474–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke JD, Reilly RA, Morrell JS, Lofgren IE. The University of New Hampshire's young adult health risk screening initiative. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(10):1751–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrell JS, Lofgren IE, Burke JD, Reilly RA. Metabolic syndrome, obesity, and related risk factors among college men and women. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(1):82–89. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.582208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schilter JM, Dalleck LC. Fitness and fatness: indicators of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk factors in college students? Journal of Exercise Physiology-Online. 2010;13(4):29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hlaing WM, Nath SD, Huffman FG. Assessing overweight and cardiovascular risk among college students. Am J Health Educ. 2007;38(2):83–90. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2007.10598948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparling PB, Beavers BD, Snow TK. Prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors in a college population. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(Suppl):S254. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199905001-01217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer L. Results of a heart disease risk-factor screening among traditional college students. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50(6):291–296. doi: 10.1080/07448480209603447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker MH (e) The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Ed Behav. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker BM, Bromme R, Jucks R. College students’ knowledge of concepts related to the metabolic syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2008;13(3):367–379. doi: 10.1080/13548500701405525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins KM, Dantico M, Shearer NB, Mossman KL. Heart disease awareness among college students. J Community Health. 2004;29(5):405–420. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHE.0000038655.19448.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green JS, Grant M, Hill KL, Brizzolara J, Belmont B. Heart disease risk perception in college men and women. J Am Coll Health. 2003;51(5):207–211. doi: 10.1080/07448480309596352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BMI for Adults [http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/obe/diagnosis.html]. Accessed March 14, 2014

- 33.Yahia N, Abdallah A, Achkar A, Rizk S. Physical Activity and Smoking Habits in Relation to Weight Status among Lebanese University Students. Int J Health Res. 2010;3(1):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Sarayra L, Khalidi R. Awareness and Knowledge about Diabetes Mellitus among Students at Al-Balqa′ Applied University. Pakistan J Nutr. 2012;11:1023–1028. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2012.1023.1028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American College Health Association . American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2013. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yahia N, El-Ghazale H, Achkar A, Rizk S. Dieting practices and body image perception among Lebanese University students. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(1):21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Diabetes Fact Sheet [http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf] Accessed March 14, 2014

- 38.Muñoz LR, Etnyre A, Adams M, Herbers S, Witte A, Horlen C, Baynton S, Estrada R, Jones ME. Awareness of heart disease among female college students. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(12):2253–2259. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf]. Accessed March 14, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.High Blood Pressure: A Look at the Causes [http://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/hbcauses.cfm]. Accessed March 14, 2014

- 41.CDC Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension—United States, 1999–2002 and 2005–2008. MMWR. 2011;60(4):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):188–197. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, Freemantle N, Petersen I. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003320. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith SC, Jr, Collins A, Ferrari R, Holmes DR, Logstrup S, Vaca McGhie D, Ralston J, Sacco RL, Stam H, Taubert K, Wood DA, Zoghbi WA. Our time: a call to save preventable death from cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) Circulation. 2012;126:2769–2775. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318267e99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W, Bao W, Begum S, Elkasabany A, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Age-related patterns of the clustering of cardiovascular risk variables of syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood in a population made up of black and white subjects. Diabetes. 2000;49(6):1042–1048. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phelan S, Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Sarwer DB, Womble LG, Cato RK, Rothman R. Impact of weight loss on the metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(9):1442–1448. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilanne-Parikka P, Eriksson JG, Lindström J, Peltonen M, Aunola S, Hämäläinen H, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Valle TT, Lahtela J, Uusitupa M, Tuomilehto J, Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group Effect of lifestyle intervention on the occurrence of metabolic syndrome and its components in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):805–807. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parikka PI, Laakso M, Eriksson JG, Lakka TA, Lindstr J, Peltonen M, Aunola S, Keinánen-Kiukaanniemi S, Uusitupa M, Tuomilehto J. Leisure-time physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1610–1617. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaoka K, Tango T. Effects of lifestyle modification on metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2012;10:138. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beibei L, Yang Y, Nieman DC, Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang R, Chen P. A 6-week diet and exercise intervention alters metabolic syndrome risk factors in obese Chinese children aged 11–13 years. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2(4):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2013.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dalleck LC, Van Guilder GP, Quinn EM, Bredle DL. Primary prevention of metabolic syndrome in the community using an evidence-based exercise program. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hawkins S, Hertweck M, Salls J, Laird J, Goreczny A. Assessing Knowledge Acquisition of Students: Impact of Introduction to the Health Professions Course. IJAHSP. 2012;10(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klesges RC, Somes G, Pascale RW, Klesges LM, Murphy M, Brown K, Williams E. Knowledge and beliefs regarding the consequences of cigarette smoking and their relationships to smoking status in a biracial sample. Health Psychol. 1988;7(5):387–401. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.7.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiner Z, Sonicki Z, Tedeschi-Reiner E. The perception and knowledge of cardiovascular risk factors among medical students. Croat Med J. 2012;53(3):278–284. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]