Abstract

The inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is negatively charged, rendering positively charged cytoplasmic proteins in close proximity likely candidates for protein-membrane interactions. YscU is a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III secretion system protein crucial for bacterial pathogenesis. The protein contains a highly conserved positively charged linker sequence that separates membrane-spanning and cytoplasmic (YscUC) domains. Although disordered in solution, inspection of the primary sequence of the linker reveals that positively charged residues are separated with a typical helical periodicity. Here, we demonstrate that the linker sequence of YscU undergoes a largely electrostatically driven coil-to-helix transition upon binding to negatively charged membrane interfaces. Using membrane-mimicking sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles, an NMR derived structural model reveals the induction of three helical segments in the linker. The overall linker placement in sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles was identified by NMR experiments including paramagnetic relaxation enhancements. Partitioning of individual residues agrees with their hydrophobicity and supports an interfacial positioning of the helices. Replacement of positively charged linker residues with alanine resulted in YscUC variants displaying attenuated membrane-binding affinities, suggesting that the membrane interaction depends on positive charges within the linker. In vivo experiments with bacteria expressing these YscU replacements resulted in phenotypes displaying significantly reduced effector protein secretion levels. Taken together, our data identify a previously unknown membrane-interacting surface of YscUC that, when perturbed by mutations, disrupts the function of the pathogenic machinery in Yersinia.

Introduction

Disorder-to-order transitions in proteins are encountered in a variety of biochemical contexts (1), such as signal transduction (2) and transcriptional regulation (3). In general, order-to-disorder transitions in proteins occur upon interaction with a template such as another protein or a membrane surface. As an example, the KIX domain of the coactivator CBP folds when bound to a phosphorylated domain of the coactivator CREB (4). Some polypeptides, such as antimicrobial peptides (5) and the Aβ peptide (6), or proteins that are intrinsically disordered in solution, including α-synuclein (7,8), adopt folded structures in the presence of lipid membranes. It has been proposed that in Escherichia coli pyruvate oxidase, an order/disorder transition within the context of a membrane binding/folding interaction is a key activation step that exposes the enzymatic binding site to pyruvate in response to reduction of enzyme-bound flavin (9). There exist two extreme models for coupled folding and binding reactions: the induced-fit (10) and conformational-selection (or one-site MWC) (11,12) models. However, recent theoretical and experimental results suggest that in practice, a complex mixture of the two models is used in these reactions (13).

Several Gram-negative bacteria use the type III secretion system (T3SS) to translocate virulence effector proteins into eukaryotic host cells (14). Upon translocation, these effector proteins counteract several immune-defense mechanisms deployed by the host, such as phagocytosis or inflammatory response (15). In Yersinia, the effector proteins are denoted Yersinia outer proteins (Yops) (16). The T3SS itself is a multiprotein machinery that includes a needle complex that spans both the inner and the outer membranes and ends with a hollow assembly through which effector proteins are believed to be threaded in a nonnative conformation (17). The protein YscU from Yersinia and its homologs in other T3SSs are important for the secretion switch from early to late substrates (18–20). YscU contains two domains, an N-terminal membrane-spanning domain (NTD) and a soluble cytoplasmic domain (YscUC) (Fig. 1 A). Residues from Ile211 through Arg239 of YscUC constitute an evolutionarily conserved linker sequence that separates the folded part of YscUC from the NTD (Fig. 1, A and B). During the secretion process, YscUC undergoes an autoproteolytic cleavage at a conserved NPTH motif. This cleavage generates a cytoplasmic C-terminal peptide (YscUCC) of ∼10 kDa and a cytoplasmic N-terminal part of YscUC (YscUCN) that remains linked to the transmembrane domain (Fig. 1 A) (21,22).

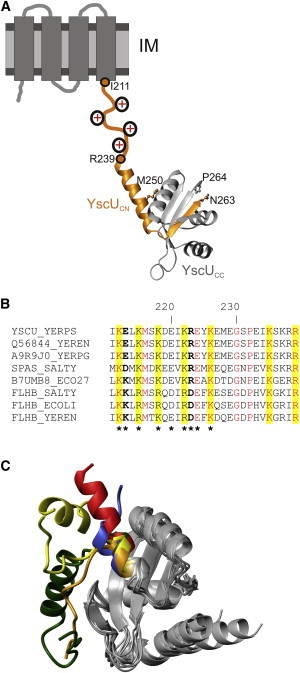

Figure 1.

YscUC structure and domain arrangements. (A) Representation of the current structural biology view of YscU (25). The membrane-spanning domain (NTD) is illustrated on an IM as four cylinders, and the evolutionarily conserved linker sequence spanning residues Ile211 and Gln239 is illustrated as an orange line with conserved positive charges added schematically. YscUC is represented by the crystallographic structure (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 2JLI (23)). The polypeptides resulting from autoproteolytic cleavage at the (N↑PTH) motif are indicated in orange (YscUCN) and gray (YscUCC). The C-terminal residue in YscUCN (Asn263) and the N-terminal residue in YscUCC (Pro264) are indicated. Met250, the first structured residue of YscUC in solution is highlighted. (B) The YscU linker sequence contains conserved positively charged side chains. Multiple sequence alignment of YscU (Y. pseudotuberculosis), SpaS (Salmonella typhimurium), EscU (Escherichia coli), and FlhB families from different organisms. Conserved residues that are positively charged are highlighted in yellow. In YscU and SpaS sequences, residues at positions 213 and 223 (bold) are negatively or positively charged, whereas they are oppositely charged in the different FlhB proteins. Asterisks indicate residues that were mutated in this study. (C) Structural plasticity of the N-terminus in YscUC and orthologs. Crystallographic structures are superimposed on the core of the autoproteolytic domains using the DALI server (26). The proteins can be identified by the colors of their N-terminal segments: red, Y. pestis YscUC (PDB 2JLI (23)); green, Y. enterocolitica YscUCN263A (PDB 2V5G (25)); yellow, E. coli EscUC (PDB 3BZL (22)); orange, E. coli EscUCT264A (PDB 3BZV (22)); and blue, S. typhimurium SpaSC (PDB 3C01 (22)).

YscUCC and YscUCN form a stable complex in solution and the crystallographic structure of this heterodimeric protein has been determined (Fig. 1 (23)). Recently, it was shown that in Yersinia, YscUCC dissociates from the remaining membrane-anchored part of YscU (i.e., NTD and YscUCN) and is subsequently secreted (24). The crystallographic structure of YscUC (23) contains an N-terminal α-helix (residues 240–255) that protrudes from the folded core of the protein. In solution, the first 10 amino acid residues in this helix are unstructured and flexible (i.e., the first folded residue is methionine 250), as shown by NMR spectroscopy (24) (Fig. 1 A). A comparison between YscUC homolog structures reveals that whereas the cores of the proteins have very similar structural topology, the N-terminal segments appear to be flexible, adopting helical and/or extended conformations (Fig. 1 C (25,26)). Taken together, it appears that the YscU family of linker sequences is disordered in solution but possesses helical propensity that enables crystallization of helical conformations.

Inspection of aligned linker sequences reveals a cluster of conserved positive charges that are distributed with a pattern reminiscent of amphipathic helical periodicity (that is, an i + 3 and i + 4 pattern) (Fig. 1 B). Given the boundary conditions that the linker sequence 1), is unstructured in solution; 2), contains stretches of residues with significant helical propensity; 3), has highly conserved positive residues arranged in an amphipathic pattern; and 4), is constrained to be in close proximity to the negatively charged bacterial inner membrane (IM), we designed biophysical experiments to test whether the linker sequence interacts with negatively charged membrane models and whether this interaction is of a disorder-to-order type. We found that the linker sequence indeed interacts with negatively charged membrane models, but it also interacts with vesicles formed from lipid extracts of E. coli inner membrane fractions. The interaction occurs in concert with a coil-to-helix transition and as such belongs to the class of proteins that undergo order-to-disorder transitions. An NMR-based structural model of the linker sequence in complex with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelles shows the presence of three helical segments. To test the biological significance of the putative linker-IM interaction, we substituted positively charged side chains found on the interaction interface with alanine. These variants displayed attenuated membrane binding affinity in vitro and significantly reduced levels of effector secretion in vivo. In summary, we have identified a disorder-to-order transition in YscU that appears to be significant for Yersinia T3SS functionality.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the Supporting Material. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or on Luria agar plates at 37°C. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis was grown at either 26°C or 37°C in LB or on Luria agar plates. Antibiotics were used for selection according to the resistance markers carried by the plasmid at concentrations of 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 100 μg/mL carbenicillin. To create calcium-depleted conditions to induce the T3SS, we added 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2 into the medium.

Purification of YscUCN variants

yscUC and yscUC6 were cloned into pGex-6p3 plasmid to produce glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins in BL21 (DE3) pLysS strain. Cultures were first grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.6; they were then shifted to 30°C and 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1 thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce protein production for 12 h. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4600 × g and pellets were stored at −80°C. Pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Tris, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.4, for sonication and centrifuged at 27,000 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were passed through a 0.45 μm syringe filter (Corning, Corning, NY) and loaded on a 5 mL GSTrap FF column (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) using an ÄKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare). GST-tagged proteins were eluted with 20 mM glutathione in 50 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.4. Fractions with the fusion protein were pooled, dialyzed against cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT), and GST was cleaved using PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) at 4°C overnight. Free GST and remaining GST-tagged protein were eliminated by binding on a GSTrap FF column. YscUC variants were further purified using cation exchange chromatography (HiTrap SP FF, GE Healthcare). Purified proteins were concentrated using centrifugal filter units (Millipore, Billerica, MA). To dissociate YscUCN from YscUCC, YscUC variants were heated to 70°C and cooled down to 20°C. This treatment triggers YscUCC precipitation, and YscUCN is recovered in the supernatant after centrifugation at 14,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. Slight modifications of the protocol described above were made for the purification of YscUCNK218A, YscUCNKE220A, and YscUCNR223A. Here, yscUCN (not yscUC) variants were cloned into pGex-6p3. GST-tagged proteins were found mostly in inclusion bodies and were dissolved in 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris, 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4. After centrifugation at 27,000 × g to eliminate urea and refold the proteins, the supernatant was stepwise dialyzed against a buffer consisting of 4 M urea, 50 mM Tris, and 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4, for 2 h at 4°C and overnight in the same buffer with no urea. Dialyzed lysates were centrifuged at 27,000 × g and 4°C and were loaded onto a 5 mL GSTrap FF column, where the purification was carried out as described above for YscUC and YscUC6. Isotopically enriched proteins 15N and 15N,13C were prepared by growing E. coli in an M9 minimal medium supplemented with 15NH4Cl and 13C-D-glucose. Samples containing SDS were prepared by adding an appropriate volume of 200 mM SDS stock solution to YscUCN in buffer.

Preparation of liposomes

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt) (DMPG), and E. coli IM lipid extract were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). DMPC or DMPG was dissolved in chloroform or chloroform/methanol (3:1), respectively, to make 2.5 mM stock solutions. Liposomes were prepared by mixing the appropriate volume of stock solutions to get the DMPC/DMPG ratios of 100:0, 95:5, 90:10, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, and 0:100. The organic solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas for 4 h and samples were dried completely under high vacuum overnight. The lipid films were resuspended in 5 mM sodium phosphate, 30 mM NaCl, and 1 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), pH 6.0, followed by four freeze-thaw vortexing cycles in liquid nitrogen. Finally, the vesicles were sonicated at 4°C until clear samples were obtained.

Circular dichroism

Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Peltier element for temperature control and a 0.1 cm quartz cuvette. Spectra were recorded from 260 to 195 nm in continuous scanning mode with a response time of 4 s, 0.5 nm steps, a bandwidth of 2 nm, and a scan speed of 50 nm/min. Five spectra were accumulated and averaged to improve the signal/noise ratio. Each spectrum was subtracted with the respective solvent spectrum background. Smoothing of data was performed with a Savitsky-Golay filter with polynomial order 3 and a window frame of 19 points (27). Concentration of added detergents was 2 mM lipid (phospholipid or E. coli IM lipid extract) or ∼20 mM SDS. For vesicle preparations, 160 μL of 2.5 mM lipid was mixed with 40 μL of 50 μM protein to obtain protein/lipid ratios of 1:200 in each sample. Lipid samples were measured in 5 mM sodium phosphate, 30 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP at pH 7.4. For SDS preparations, 270 μL of 100 μM protein was mixed with 30 μL of 200 mM SDS. SDS samples were measured in 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4. All samples were homogenized with a vortexer and allowed to equilibrate for at least 15 min before measurement.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR measurements were performed at a YscUCN concentration of 100 μM in 30 mM sodium phosphate and 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.0, with 26 mM SDS and 8% v/v D2O as a lock solvent. NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker 600 MHz Avance III spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm HCN cryprobe with z-axis gradients, using pulse programs from the Bruker library. Temperature calibration was obtained before NMR measurements were taken with a home-built temperature probe inserted into the sample compartment. NMR spectra were processed with NMRPipe (28) and visualized in Ansig for Windows (29) and CcpNmr (30). Resonance assignments of YscUCN in complex with SDS micelles were obtained from 15N NOESY heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC), 15N TOCSY-HSQC (31,32), HNHA (33), HNCA, and HN(CO)CA (34) experiments. Residue-specific secondary structure predictions from pooled 1HN, 1Hα, 13Cα, and 15N chemical shifts were generated with the program MICS (35). Deviations Δδ = δobs − δrc of observed from random coil shifts were computed using the reference random coil shift database employed by the program MICS (36–38) MICS also provided values of the random coil index (RCI) (39), offering an independent assessment of backbone root mean-square fluctuations to supplement the order parameters derived from spin relaxation measurements. Experimental details regarding structure calculations, amide exchange, pH perturbation, and spin relaxation measurements are outlined in the Supporting Material.

The translational diffusion coefficient of YscUCN in buffer with 26 mM SDS 8% (v/v) D2O/H2O was measured at 36.5 ± 0.2°C with a PFG-STE pulse program using binomial pulses for water suppression and a diffusion delay of 100 ms. Amide resonances were integrated and the signal decays fit with a single exponential function by nonlinear least squares to derive the initial signal amplitude, I0, and diffusion coefficient, D, according to the Stejskal-Tanner equation (40,41):

| (1) |

Here, Δ is the effective diffusion delay and q = γδG, where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, and δ and G are the gradient pulse length and amplitude, respectively. Uncertainties in the fitted parameters were estimated from the root mean-square residuals and the covariance matrix from the fits. The diffusion coefficient of the YscUCN micellar complex was converted into an effective hydrodynamic radius according to the Stokes-Einstein equation (42):

| (2) |

Here, η is the dynamic viscosity of the solvent, rH is the hydrodynamic radius, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Finally, the hydrodynamic radius was translated into a rotational correlation time using the rotational Stokes-Eintein-Debye equation:

| (3) |

where V is the volume of the tumbling particle, assumed spherical with radius rH. A value of η = 0.709 cP for 8% (v/v) D2O in H2O at 36.5°C was used in all calculations.

Transverse paramagnetic relaxation enhancements (PREs) were determined by monitoring the effect of doxyl-5-stereate (D5S) and Mn2+ on the crosspeak volumes in 1H-15N HSQC spectra of YscUCN. Mn2+ PRE spectra were acquired at MnCl2 concentrations of 0, 31, 88, 161, and 225 μM. Measurements with D5S were performed at PRE agent concentrations of 0, 0.43, and 1.93 mM. Crosspeak volumes, V, were fit with Eq. 4 to obtain the transverse PRE rate Γ2 (43)

| (4) |

where c is the molar concentration of relaxation agent, τ is the total time during which magnetization is transverse, and R2 is the effective transverse relaxation rate, estimated as 15N R2.

Complementation assay

ΔyscU (pIB75) strain was transformed with pBAD plasmids encoding either yscUwt or different yscU point mutants and grown in LB containing both kanamycin and carbenicillin. Cultures in calcium-depleted conditions were started at OD600 = 0.1, grown at 26°C for 1 h, and shifted to 37°C for 3 h. To analyze Yop secretion, cultures were processed according to the protocol described by Frost and colleagues (24) with some modifications. 9 mL of filtrated supernatant was precipitated with 10% (v/v) of trichloroacetic acid. Cells and supernatants were loaded according to OD600 and separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were either stained with Coomassie R250 or, alternatively, transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for immunoblotting. Anti-Yop and anti-YscU antibodies were diluted 1:5000. Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was diluted at 1:10,000 (GE Healthcare). Proteins were detected with a chemiluminescence detection kit (GE Healthcare).

Surface localization of YscF

Surface-localized YscF was analyzed according to the protocol previously described by Edqvist et al. (20), with some modifications. Strains were grown as described above, then gently pelleted and resuspended in LB. The concentrated pellets were sheared by five passages through a hypodermic needle (23G × 1; 0.6 × 25 mm; Braun, Melsungen, Germany) to release surface proteins from the bacterial surface. After centrifugation, sheared supernatants were separated by 15% Tris-Tricine SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for Immunoblot analysis with anti-YscF antibodies (1:5000 dilution).

Results and Discussion

Since the IMs of Gram-negative bacteria contain significant amounts of negatively charged lipids (44) and the YscUC linker sequence is enriched in positively charged residues distributed with an amphipathic helical periodicity, we speculated that the linker can interact with the IM via electrostatic interactions while in a helical conformation. To test this hypothesis we studied the interaction between YscUC and YscUCN with lipid membrane models of varying complexity. These models that mimic biological membranes range from IM lipid fractions extracted from E. coli to glycerophospholipid vesicles composed of varying mixtures of neutral DMPC and negatively charged DMPG lipids to SDS micelles.

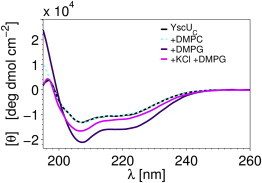

YscUC interacts with negatively charged glycerophospholipid vesicles

To study interactions between YscUC and membranes, lipid vesicles with a range of negative surface charges were prepared by varying the amount of anionic DMPG lipids incorporated into neutral DMPC bilayers. Far-ultraviolet (far-UV) circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is particularly suited to monitor conformational changes in the protein resulting from its association with the membrane (45). As seen in Fig. 2, addition of highly charged DMPG vesicles to YscUC induces pronounced features in CD bands (208 and 220 nm) that are typical markers for helical secondary structures. These features are much less pronounced in the presence of neutral DMPC vesicles and in the vesicle-free case. This observation is a clear indication that YscUC indeed can interact with membranes containing anionic lipids, as in the case of the IM, a process that is accompanied by an increase in the helical features of the protein. Since YscUC does not interact with neutral DMPC vesicles (Fig. 2), the observed interaction is likely caused by electrostatic attraction between basic residues of the protein and the vesicles containing acidic lipid. Fully consistent with a primarily electrostatically driven mechanism, the interaction between YscUC and DMPG vesicles is screened by addition of potassium chloride (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

YscUC interacts with negatively charged phospholipid vesicles. The interaction between YscUC and vesicles was probed with far-UV CD spectroscopy in a buffer consisting of 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4 and a temperature of 37°C. CD spectra were acquired in buffer (black) in the presence of DMPC (zwitterionic; dashed light blue) or DMPG vesicles (anionic; violet). Addition of 100 mM KCl (magenta) attenuated the interaction between YscUC and DMPG vesicles.

Despite the absence of an increase in helical features upon addition of DMPC, it is possible that the peptide partitions to the membrane interface in a disordered state that would be silent to CD. To check this possibility, we estimated free energies of transfer from water to a neutrally charged membrane environment using the Wimley-White water/interface (w/if) hydrophobicity scale, which describes specifically the free energy of transfer of residues (including peptide bond) within short disordered peptides from water to the interface of POPC large unilamellar vesicles (46). In addition, we calculated traditional hydrophobicities in the form of free energies of transfer from water to octanol (w/o), which is a useful measure of the relative propensity for partitioning to the hydrophobic membrane interior. The large positive values of the w/o and w/if free energies compiled in Table S4 for the entire protein and for individual helices reveal that transfer to a neutral membrane interface or apolar interior is generally disfavored. This is expected for a peptide with such a high proportion of charged residues and supports instead electrostatic attraction as the main driving force for partititioning of the peptide to the vesicle membrane. As a consequence, gain of helical structure can serve as a reporter of binding, and the absence of structure indicates negligible binding to the model membranes used in this study.

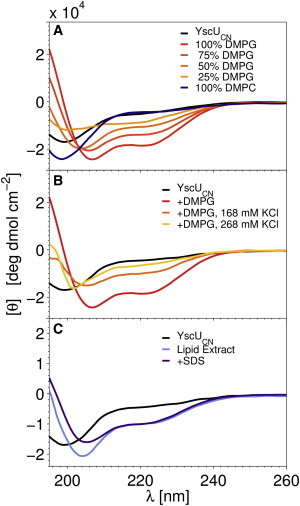

Coil-to-helix transition of YscUCN

To further characterize the nature of the interactions of YscUC with negatively charged lipids, we purified YscUCN (residues 211–263; Fig. 1 A) and studied its interaction with model membrane systems with different surface potentials and of varying chemical complexity. YscUCN is unstructured in a vesicle-free solution, as indicated by the CD and NMR spectra (Figs. 3 A and 4). Like YscUC, YscUCN interacts with anionic lipid vesicles, and this interaction and associated structural changes are strongly correlated with the membrane surface charge density (i.e., the ratio of DMPG to DMPC) as the CD signal varies in a dose-dependent manner with DMPG ratio. The interaction includes an electrostatic component, since it is attenuated in the presence of KCl (Fig. 3 B). The CD spectra suggest that YscUCN also undergoes a coil-to-helix transition as a consequence of its association to negatively charged membranes. The nearly complete loss of random-coil character indicated by the CD response reveals that YscUCN is a key site involved in a membrane interaction accompanied by folding of the linker region (Fig. 1 A). YscUCN also interacts with SDS micelles and lipid extracts from E. coli IM preparations (Fig. 3 C). Since E. coli and Yersinia IM lipids are similar, it is plausible that the protein-membrane interaction also takes place in vivo in Y. pseudotuberculosis. The interaction with SDS micelles is important, since it enables a detailed structural characterization of the YscUCN-membrane interaction with NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 3.

YscUCN undergoes a coil-to-helix transition upon binding to negatively charged phospholipid vesicles. The interaction between YscUCN and different membrane models was probed with far-UV CD as in Fig. 2. (A) The YscUCN interaction with negatively charged phospholipid vesicles (DMPG) is proportional to negative charge density. (B) KCl attenuates the YscUCN interaction with DMPG vesicles in a dose-dependent manner. (C) YscUCN interacts with SDS micelles (purple) and E. coli IM lipid extracts (light blue) with a CD response similar to that observed with DMPG vesicles.

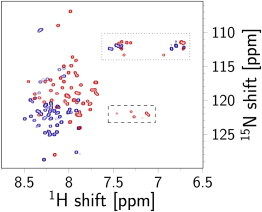

Figure 4.

Interaction between YscUCN and SDS micelles probed with NMR spectroscopy. 1H-15N HSQC spectra of YscUCN in 30 mM NaPi and 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.0 (blue), and in the presence of 26 mM SDS (red). The significantly improved signal dispersion of YscUC when bound to SDS micelles indicates that the protein undergoes a structural rearrangement upon micelle binding. Arginine and glutamine/asparagine side-chain resonances are enclosed in dashed and dotted boxes, respectively.

YscUCN structure in complex with SDS micelles

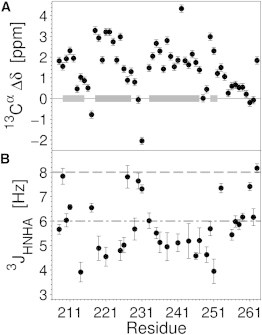

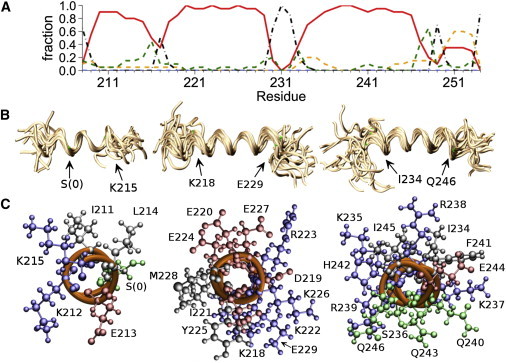

To identify the amino acid residues in YscUCN directly involved in the membrane-induced formation of helical segments, we used high-resolution NMR spectroscopy on 15N isotopically enriched YscUCN in complex with negatively charged SDS micelles. Although SDS micelles represent a very basic model of a biological membrane (but contain the characteristic amphiphilic features of a negative surface potential and hydrophobic core), they allow measurement of high-resolution structural information with NMR spectroscopy. The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of YscUCN in complex with SDS micelles displays well dispersed signals (Fig. 4, red) and is significantly shifted from a spectrum obtained in buffer (Fig. 4, blue), suggesting that YscUCN forms a stable complex with SDS micelles. An NMR-based determination of the translational diffusion coefficient was used to estimate the size of the protein micelle complex. The diffusion NMR data were satisfactorily fit by a single exponential according to Eq. 1, with uncertainties in D of ±2%. Introduction of a second exponential term did not significantly improve the fits according to an F-statistic. The fitting parameters were insensitive to an increase in the diffusion time from 100 ms to 200 ms. Taken together, the data suggest a reasonable estimate of 1.40 ± 0.03 × 10−10 m2/s at 36.5°C, which translates to a Stokes hydrodynamic radius of 2.28 ± 0.05 nm. The radius is comparable to previously reported sizes for an SDS micelle (2.34 nm at cSDS = 26 mM and cNa+ = 80 mM (47)). To derive molecular details on the peptide-micelle interaction, the backbone resonances of YscUCN were assigned in the micelle-bound state using standard NMR approaches (48). Analysis of chemical shifts (35) shows that when interacting with SDS micelles, YscUCN forms three α-helices comprised of more than five residues (Fig. 5 A). The existence of these helices is further supported by the magnitudes of three-bond 3JHNHA couplings (Fig. 5 B) and sequential nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) patterns (Fig. S1). Thus, the NMR observations reinforce the conclusion from CD spectroscopy that YscUCN undergoes a coil-to-helix transition upon interaction with a negatively charged membrane surface. From NMR structural restraints, an ensemble of conformations (deposited at the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics under Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 2ml9) representative of the helical stretches within SDS-bound YscUCN was derived (Fig. 6). Three longer α-helices are evident spanning residues S[0]–K215, K218–E229, and I234–Q246 (residue S[0] is one of the residues encoded by the plasmid multiple cloning site that remain attached to the YscUCN N-terminus after the GST-tag cleavage). Interestingly, the helical segments identified in the presence of SDS agree with secondary structure predictions generated with the PSI-PRED algorithm (49,50) (Fig. S1) and are therefore consistent with similar folded units identified in globular and transmembrane proteins. Molecular structures (Fig. 6) were aligned and rendered with the VMD program (51).

Figure 5.

NMR identification of helical segments of YscUCN in complex with SDS micelles. (A) Deviation (Δδ) of observed 13Cα chemical shifts from random-coil values are displayed against the primary sequence of YscUCN. Gray horizontal bars indicate α-helical regions identified by the program MICS (35), with darker tone indicating rigid helices (see Supporting Material). (B) 3JHNHα couplings in SDS-bound YscUCN. Horizontal lines indicate standard cutoffs (48) used during classification of backbone conformations (<6 Hz, α-helical (dash-dotted gray line); >8 Hz, extended (dashed gray line)).

Figure 6.

Structure of YscUCN in complex with SDS micelles computed from NMR restraints. (A) Occupation of different secondary-structure conformations by each residue, averaged over the structure ensemble. Red, α-helix; dashed yellow, 310 helix; dashed green, turn; dash-dotted black, bend or coil. (B) Backbone alignments for helices 1–3, showing an ensemble of 20 low-energy conformers. Backbones are rendered as golden coils. Positions of Cα atoms at the edges of the aligned segments corresponding to the helix boundaries are marked with green dots and labeled with arrows. (C) View along the long axis (from C to N terminus) of the first three helices of YscUCN, emphasizing amphipathic helical residue distributions. Backbone atoms are rendered as orange coils and side chains in ball-and-stick format colored according to residue polarity and charge: blue, basic (H, K, and R); red, acidic (D and E); green, polar (S and Q); black, = nonpolar (I, F, M, and Y). Molecular structures were aligned and rendered with the VMD program (51).

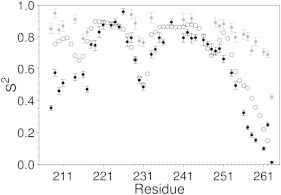

The fast-timescale (picoseconds to nanoseconds) dynamics of the helices was evaluated via NMR-derived order parameters obtained from spin relaxation rates (Fig. S2) and validated independently by chemical-shift measurements via the RCI algorithm (39). The order parameter (S2) is well suited for quantitative analysis of fast (picoseconds to nanoseconds) internal motions in proteins. It adopts values between 0 and 1, describing the limits of unrestricted versus fully restricted motion on the picosecond-to-nanosecond timescale. Amino acid residues in secondary-structure elements in folded globular proteins usually have order parameters in the range 0.75–0.95 (52). For YscUCN in complex with SDS micelles it was found that helices 2 and 3 have order parameters with a magnitude resembling those of globular proteins, whereas residues in helix 1 have significantly smaller values and consequently are more dynamic on the picosecond-to-nanosecond timescale compared to helices 2 and 3 (Fig. 7). Since helix 1 forms one unit on the basis of NOE connectivities and chemical shifts, it is likely that this helix fluctuates between alternate positions relative to the remainder of the protein.

Figure 7.

Dynamics of YscUCN in complex with SDS. Amplitude of fast-timescale motion (picoseconds to nanoseconds) was quantified by order parameters derived from NMR spin relaxation (S2 and S2fast, evaluated at τM = 7.7 ns) and chemical shifts (S2RCI). Solid circles, S2; gray circles, S2fast; open circles, S2RCI.

Helix 2 is initiated by a well defined and conserved N-terminal helix-capping (Ncap) box motif verified by the knowledge-based primary sequence and chemical-shift analysis performed with the program MICS. The Ncap is formed by Ser217, which can form a hydrogen bond via its side chain to the backbone amide of Glu220, and a weak NOE is observed between Ser Hβ and Glu HN, suggesting transient bonding. Helix 3 also displays clear amphipathic periodicity. Although MICS failed to identify probable capping boxes or other bounding motifs in this region, the experimental data are consistent with initiation of the helix at I234 and termination near Q246 (see Fig. 6 A). Helices 2 and 3 are separated by the sequence Gly-Ser-Pro-Glu, which is consistent with a type VIα2/β β-turn (βαR or ββ in Ramachandran notation). The key glycine and proline residues in the series are highly conserved (nearly 100%) among YscUC homologs, and the turn may therefore be of importance for T3SS function.

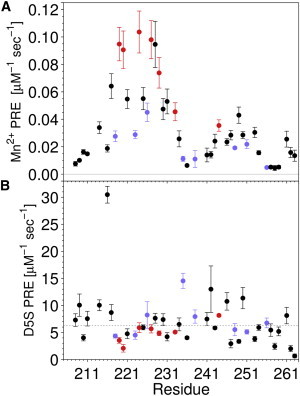

Positioning of YscUCN in SDS micelles

The positioning of YscUCN within the micellar complex was probed by quantifying the effects of paramagnetic substances added to the bulk solution (Mn2+) or incorporated into the micelle itself in the form of a spin label containing fatty acids (53). Close proximity of a nucleus to the paramagnetic agent enhances NMR spin relaxation, resulting in quantifiable line broadening of NMR resonances. Addition of Mn2+ ions to the bulk solution resulted in PREs that are most pronounced for residues in helix 2 and less so for those in helices 1 and 3 (Fig. 8 A). These results suggest that helix 2 is located near the surface of the micelle, whereas helices 1 and 3 are more deeply immersed in the hydrophobic core of the micelle. In addition, PREs in helix 2 are most prominent for the acidic glutamic and aspartic acid residues (Fig. 8 A, red) and weakest for the basic arginine and lysine residues (in blue), which matches the amphipathic pattern of residues in the helices (see Fig. 6 A) and is consistent with an interaction primarily driven by positive charges in YscUCN. To probe the micellar localization in more detail, additional experiments using micelles doped with D5S were performed. Regions of YscUC buried within the micelle will be situated closer to the spin-label segment of D5S and thus experience a stronger PRE (see Fig. 8 B). Corresponding NMR measurements confirm the buried location of helices 1 and 3 as they display an enhanced PRE. An independent probe of the positioning of YscUCN within the SDS-micellar complex was provided by chemical-shift changes in response to a perturbation of the aqueous buffer surrounding the micelles from pH 6 to 7. In particular 1HN and 15N chemical shifts of residues localized in the vicinity of sulfate headgroups at the micellar interface display an amplified sensitivity to buffer pH changes compared to resonances removed from the interface (54) (Figs. S1 and S3). The pH response also places helix 2 at an interfacial location and the other helices at positions more distant from the interface. Amide hydrogen-to-deuterium exchange rates also inform on the position of YscUCN segments within the complex, as their magnitude depends on the extent of solvent exposure. A helix on the surface of a micelle is expected to show less protection against exchange compared to a helix embedded in the micellar core. Quantification of these exchange rates by the CLEANEX approach (55) show that residues in helices 1 and 3 are most protected (Figs. S1 and S4), again substantiating that helix 2 is located at the micelle surface, whereas helices 1 and 3 are less accessible to the solvent. The results of the positioning experiments are consistent with Wimley-White hydrophobicities and Eisenberg hydrophobic moments computed for helices 1–3 (Table S4). The hydrophobicities suggest that compared to helices 1 and 3, helix 2 has a reduced preference for the hydrophobic environment of a micelle or membrane, and the hydrophobic moments indicate that helix 2 would favor an interfacial location relative to the other helices.

Figure 8.

Relative solvent exposure of YscUCN residues in the presence of SDS micelles. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancements from titration of SDS-YscUCN complexes with Mn2+ (A) or D5S (B). Red, acidic residues (E and D); blue, basic residues (K and R).

It should be noted that differences in the dimensions and chemical composition of an SDS micelle and a phospholipid membrane could alter preferences in location. In particular, constraints imposed upon the dimensions of the SDS complex by the solvation preferences of the amphiphile can be expected to compete with the interactions between helices and to affect the relative positioning of the helices. However, the NMR positioning experiments performed in SDS are useful in providing evidence for interfacial localization of the helices and describing the relative exposure of the individual residues.

Disruption of the YscUC-membrane interaction affects Yop secretion in vivo

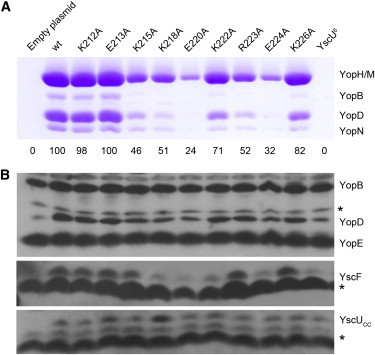

The biophysical experiments suggest that the YscUC-membrane interaction is mainly driven by electrostatic attractions, since either incorporation of zwitterionic lipid or addition of salt interfere with YscUC binding to vesicles. In addition, NMR experiments place helix 2 of YscUCN at the membrane surface. To test whether the proposed membrane interaction in YscUC is of biological relevance, we performed an alanine scanning mutagenesis toward the positively charged residues within helix 2 and measured the ability of these variants to complement Yop secretion. In a complementation assay, the introduction of a plasmid-encoded copy of yscU into a ΔyscU strain (i.e., a strain lacking yscU gene) restores Yop secretion once the T3SS is activated. The T3SS can be activated by shifting growing bacteria from 26°C to 37°C with a simultaneous depletion of Ca2+ from the culture medium by addition of 5 mM EGTA. Hence, depletion of Ca2+ and temperature increase are invaluable tools used in the laboratory to mimic the bacterial host cell contact needed for T3SS activation (16). Complementation of Yop secretion was then assayed by introducing plasmids expressing full-length mutated yscU in a ΔyscU strain. At first, we used the variant denoted YscU6 that contains six alanine substitutions (K212A, K215A, K218A, K222A, R223A, and K226A) to test a variant where the membrane interaction is expected to be removed. Both the empty plasmid and the plasmid-encoding wild-type yscU were used as controls to demonstrate the validity of the complementation assay. No complementation of Yop secretion was observed with YscU6 (Fig. 9 A), even though the immunoblot showed that similar amounts of Yops were present in the cell pellets (Fig. 9 B). Thus, the positively charged residues within helices 1 and 2 are essential for YscU function, and the absence of complementation by YscU6 is probably due to its inability to interact with the IM.

Figure 9.

Complementation assays to probe the YscUC-membrane interaction in vitro. The Yop secretion complementation assay was performed using a ΔyscU strain. (A) Coomassie-stained gel corresponding to trichloroacetic acid precipitated culture supernatants. To compare the complementation efficiency of the different variants, the YopH/M band was quantified by densitometry using MultiGauge software (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The secretion efficiency has been set to 100 for the strain transformed with the plasmid encoding yscUwt. Quantification results are listed below the gel. (B) Cell pellet immunoblots carried out with anti-Yop (upper) and anti-YscUCC (lower) antibodies and shared supernatants analyzed with an anti-YscF antibody (center). Asterisks indicate unspecific bands. To see this figure in color, go online.

To determine which of those six residues are most important for YscU function, complementation assays were performed with YscU variants containing single substitutions. No significant difference in the level of effector secretion was detected between the wild-type and YscUK212A. This result is somewhat surprising considering the degree of conservation of K212 within T3SS homologs (Fig. 1 B), and it suggests that this residue is not crucial for YscU function in secretion. A decrease of ∼30% and 20% of Yop present in the supernatant was observed for YscUK222A and YscUK226A, respectively (Fig. 9). YscUK215A, YscUK218A, and YscUR223A are the most affected single-substitution variants, with only 50% of secreted Yop compared to the wild-type. None of the single mutants abolished Yop secretion as YscUC6 did, indicating that residues at positions 215, 218, 222, 223, and 226 all participate in the interaction with membranes. It is important to note that synthesis of the effectors is not affected by these substitutions, since a similar amount of Yop was detected in the cell pellets (Fig. 9 B). Furthermore, the amount of secreted YscF, the needle subunit that is an early substrate, is also affected. In fact, the amount of secreted effectors is generally proportional to the amount of secreted YscF. These results show that both early substrates and effectors are affected in these mutants.

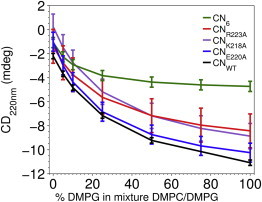

Mutations of YscUCN at positively charged residues influence the interaction with anionic liposomes

The complementation data presented above suggest that the positively charged residues within YscUCN helices 1 and 2 are critical for YscU function in vitro. To correlate the complementation ability of the different variants with their capacity to interact with negatively charged model membranes we developed a CD-based protocol to measure their interaction with vesicles of varying negative charge density. The-signal at 220 nm (intensity used as a reporter of helical structure) was monitored for the different mutants in a buffer with or without vesicles with different surface charges. For clarity, the mutations in this section are referred to as CNX, where CN corresponds to YscUCN and subscript X defines the mutation position in the peptide sequence. The results displayed in Fig. 10 show that the capacity of CN6 (variant with six substitutions) to interact with the model membrane is significantly reduced compared to the wild-type variant (CNWT). This result strongly supports a correlation between the membrane interaction measured in vitro and the in vivo function of the YscU linker within the T3SS. For the two point mutants CNK218A and CNR223A, the membrane-interacting capacity is intermediate between the two limiting cases that are CNWT and CN6, which then correlates with partial loss of Yop secretion for these substitutions. Taking all the data together, we observe a correlation between Yop secretion in vivo and membrane-binding capacity in vitro. This observation suggests that the membrane interaction by the linker sequence of YscU is of biological significance. In the model proposed here, the cationic surface of the linker sequence binds to negatively charged membranes in a helical conformation. This raises the possibility that the opposite, solvent-accessible, surface may constitute a binding site for other proteins involved in the secretion process. To test this, we made two point mutations of negatively charged and presumably solvent-exposed side chains (CNE220A and CNE224A). Both these substitutions resulted in a significant reduction of effector secretion levels (Fig. 9) while leaving the membrane interaction affinity unaltered compared to that of the wild-type (Fig. 10). These results are consistent with a protein interaction site at the solvent-exposed side of helix 2 that is of functional relevance for effector secretion.

Figure 10.

Binding of YscUCN and variants to vesicles. The binding capacity of YscUCN variants to vesicles with varying anionic charge density was probed by observing the CD signal at 220 nm. CD spectra were recorded at 20°C in 5 mM sodium phosphate, 30 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP at pH 6.0. The data were analyzed with a one-site binding model (solid lines) and the binding capacity is judged from the maximum amplitude of the CD signal. Black, CNWT; green, CN6; red, CNR223A; purple, CNK218A; blue, CNE220A.

Conclusion

We have found that the linker sequence separating the membrane-spanning and soluble cytoplasmic domains of YscU interacts with negatively charged model membranes. This interaction is dominated by electrostatic contributions, since salt addition attenuates the binding. The interaction is accompanied by extensive acquisition of helical structure. A structural model derived using SDS as a membrane mimic indicates that three helices form in regions that demonstrate clear amphipathic patterns of residue distribution. NMR structural restraints and dynamics measurements indicate that helix 2 has a stable α-helical structure distinctly delineated by strictly conserved features in the amino acid sequence, including helical initiation and termination sites. Together, our observations point to a cooperative (all-or-none) electrostatically mediated binding process. Since the linker sequence is disordered in solution, the membrane induces a disorder-to-order transition. Coupled folding and binding events by unstructured proteins can in principle occur with mixtures of induced fit (10) or conformational selection (11,12) models, but from our equilibrium experiments we cannot distinguish between these models. Disorder-to-order transitions have been observed for other aspects of the T3SS; for instance, YopE undergoes a coupled folding-binding event upon interaction with its chaperone SycE (56). The sequence separating helices 2 and 3 is consistent with a type-VIa/b β-turn and suggests that the helices are primed for an antiparallel alignment, but only when an essential Pro residue in the turn adopts an N-terminal cis-amide conformation.

It was found that YscUC interacts with lipid vesicles from E. coli IM extracts, and since the IMs of Gram-negative bacteria are similar, it is likely that some of the interactions we observe with model membranes also occur inside Yersinia cells. From a functional standpoint, we have found a correlation between the in vitro membrane-binding capacity of mutated YscUc variants and Yop secretion complementation ability of these mutations when introduced in full-length YscU. From these observations, we propose a model in which the linker sequence of YscU binds to the Yersinia IM and suggest that this interaction is important for effector secretion via the T3SS. Supporting our findings, previous works in which mutagenesis toward the linker sequence from E. coli EscU (22) and Salmonella FlhB (57) showed that small deletions, as well as Proline introduction within the linker sequence, drastically affected T3SS functionality. We propose that membrane interaction would be critical for YscU to be placed in the correct position in relation to the T3SS to fulfill its function. Given the strong linker-sequence conservation between YscU homologs, it is likely that the model proposed here is of relevance also in many other Gram-negative bacterial species.

Author Contributions

We thank Konrad Cyprych for assistance with preparation of lipid vesicle samples and Radek Sachl for helpful discussions. Parts of subcloning and protein purification were planned and performed by the Umeå Protein Expertise Platform. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council (M.W.W., H.W.W., and G.G.), an Umeå University Carrier Award to M.W.W., and post-doc support to F.L. from the Umeå Centre for Microbial Research. We acknowledge the Kempe Foundation and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation for funding of the NMR infrastructure.

Footnotes

Christoph F. Weise and Frédéric H. Login contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material

Supporting Citations

References (58–79) appear in the Supporting Material.

References

- 1.Radivojac P., Iakoucheva L.M., Dunker A.K. Intrinsic disorder and functional proteomics. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1439–1456. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uesugi M., Nyanguile O., Verdine G.L. Induced α helix in the VP16 activation domain upon binding to a human TAF. Science. 1997;277:1310–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5330.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radhakrishnan I., Pérez-Alvarado G.C., Wright P.E. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of CREB: a model for activator:coactivator interactions. Cell. 1997;91:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by α-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aisenbrey C., Borowik T., Gröbner G. How is protein aggregation in amyloidogenic diseases modulated by biological membranes? Eur. Biophys. J. 2008;37:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliezer D., Kutluay E., Browne G. Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:1061–1073. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varkey J., Isas J.M., Langen R. Membrane curvature induction and tubulation are common features of synucleins and apolipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32486–32493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann P., Weidner A., Tittmann K. Structural basis for membrane binding and catalytic activation of the peripheral membrane enzyme pyruvate oxidase from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17390–17395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koshland D.E. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1958;44:98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange O.F., Lakomek N.A., de Groot B.L. Recognition dynamics up to microseconds revealed from an RDC-derived ubiquitin ensemble in solution. Science. 2008;320:1471–1475. doi: 10.1126/science.1157092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J.P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogan J., Gianni S., Jemth P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:6323–6331. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54226b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galán J.E., Wolf-Watz H. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature. 2006;444:567–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mota L.J., Cornelis G.R. The bacterial injection kit: type III secretion systems. Ann. Med. 2005;37:234–249. doi: 10.1080/07853890510037329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornelis G.R., Wolf-Watz H. The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:861–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2731623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radics J., Königsmaier L., Marlovits T.C. Structure of a pathogenic type 3 secretion system in action. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:82–87. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minamino T., Macnab R.M. Domain structure of Salmonella FlhB, a flagellar export component responsible for substrate specificity switching. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:4906–4914. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4906-4914.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams A.W., Yamaguchi S., Macnab R.M. Mutations in fliK and flhB affecting flagellar hook and filament assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:2960–2970. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2960-2970.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edqvist P.J., Olsson J., Lloyd S.A. YscP and YscU regulate substrate specificity of the Yersinia type III secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:2259–2266. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2259-2266.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Björnfot A.C., Lavander M., Wolf-Watz H. Autoproteolysis of YscU of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is important for regulation of expression and secretion of Yop proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:4259–4267. doi: 10.1128/JB.01730-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarivach R., Deng W., Strynadka N.C. Structural analysis of the essential self-cleaving type III secretion proteins EscU and SpaS. Nature. 2008;453:124–127. doi: 10.1038/nature06832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lountos G.T., Austin B.P., Waugh D.S. Atomic resolution structure of the cytoplasmic domain of Yersinia pestis YscU, a regulatory switch involved in type III secretion. Protein Sci. 2009;18:467–474. doi: 10.1002/pro.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost S., Ho O., Wolf-Watz M. Autoproteolysis and intramolecular dissociation of Yersinia YscU precedes secretion of its C-terminal polypeptide YscU(CC) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiesand U., Sorg I., Heinz D.W. Structure of the type III secretion recognition protein YscU from Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:854–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holm L., Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenfield N.J. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2876–2890. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helgstrand M., Kraulis P., Härd T. Ansig for Windows: an interactive computer program for semiautomatic assignment of protein NMR spectra. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;18:329–336. doi: 10.1023/a:1026729404698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vranken W.F., Boucher W., Laue E.D. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer A.G., Cavanagh J., Rance M. Sensitivity improvement in proton-detected two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 1991;93:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kay L.E., Keifer P., Saarinen T. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vuister G.W., Bax A. Quantitative J correlation: a new approach for measuring homonuclear 3-bond J(HNHα) coupling constants in 15N-enriched proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:7772–7777. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grzesiek S., Bax A. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. J. Magn. Reson. 1992;96:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y., Bax A. Identification of helix capping and b-turn motifs from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;52:211–232. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornilescu G., Delaglio F., Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spera S., Bax A. Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cβ13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wishart D.S., Bigam C.G., Sykes B.D. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berjanskii M.V., Wishart D.S. The RCI server: rapid and accurate calculation of protein flexibility using chemical shifts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W531–W537. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price W.S. Pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance as a tool for studying translational diffusion: Part II. Experimental aspects. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1998;10:197–237. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stejskal E.O., Tanner J.E. Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. J. Chem. Phys. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price W.S. Pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance as a tool for studying translational diffusion. 1. Basic theory. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1997;9:299–336. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Battiste J.L., Wagner G. Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5355–5365. doi: 10.1021/bi000060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silhavy T.J., Kahne D., Walker S. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unnerståle S., Mäler L., Draheim R.R. Structural characterization of AS1-membrane interactions from a subset of HAMP domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:2403–2412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White S.H., Wimley W.C. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quina F.H., Nassar P.M., Bales B.L. Growth of sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles with detergent concentration. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:17028–17031. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cavanagh J., Fairbrother W.J., Skelton N.J. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buchan D.W., Ward S.M., Jones D.T. Protein annotation and modelling servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W563–W568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones D.T. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodman J.L., Pagel M.D., Stone M.J. Relationships between protein structure and dynamics from a database of NMR-derived backbone order parameters. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:963–978. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarvet J., Danielsson J., Gräslund A. Positioning of the Alzheimer Aβ(1–40) peptide in SDS micelles using NMR and paramagnetic probes. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;39:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheftic S.R., Croke R.L., Atexandrescu A.T. Electrostatic contributions to the stabilities of native proteins and amyloid complexes. Methods Enzymol. 2009;466:233–258. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)66010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang T.L., van Zijl P.C., Mori S. Accurate quantitation of water-amide proton exchange rates using the phase-modulated CLEAN chemical EXchange (CLEANEX-PM) approach with a Fast-HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;11:221–226. doi: 10.1023/a:1008276004875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodgers L., Gamez A., Ghosh P. The type III secretion chaperone SycE promotes a localized disorder-to-order transition in the natively unfolded effector YopE. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20857–20863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802339200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fraser G.M., Hirano T., Macnab R.M. Substrate specificity of type III flagellar protein export in Salmonella is controlled by subdomain interactions in FlhB. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:1043–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laskowski R.A., Macarthur M.W., Thornton J.M. Procheck: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabsch W., Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eisenberg D., Weiss R.M., Terwilliger T.C. The hydrophobic moment detects periodicity in protein hydrophobicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:140–144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kay L.E., Torchia D.A., Bax A. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori S., Abeygunawardana C., van Zijl P.C. Improved sensitivity of HSQC spectra of exchanging protons at short interscan delays using a new fast HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme that avoids water saturation. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1995;108:94–98. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bai Y., Milne J.S., Englander S.W. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Connelly G.P., Bai Y., Englander S.W. Isotope effects in peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:87–92. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Markley J.L., Bax A., Wüthrich K. Recommendations for the presentation of NMR structures of proteins and nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:933–952. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mandel A.M., Akke M., Palmer A.G., 3rd Backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI: correlations with structure and function in an active enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:144–163. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fushman D., Cahill S., Cowburn D. The main-chain dynamics of the dynamin pleckstrin homology (PH) domain in solution: analysis of 15N relaxation with monomer/dimer equilibration. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:173–194. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hall J.B., Fushman D. Characterization of the overall and local dynamics of a protein with intermediate rotational anisotropy: differentiating between conformational exchange and anisotropic diffusion in the B3 domain of protein G. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;27:261–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1025467918856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wennerst H. Nuclear magnetic relaxation induced by chemical exchange. Mol. Phys. 1972;24:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lipari G., Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic-resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lipari G., Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 2. Analysis of experimental results. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clore G.M., Szabo A., Gronenborn A.M. Deviations from the simple two-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic relaxation of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ortega A., de la Torre J.G. Hydrodynamic properties of rodlike and disklike particles in dilute solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:9914–9919. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma K., Clancy E.L., Zagorski M.G. Residue-specific pKa measurements of the β-peptide and mechanism of pH-induced amyloid formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8698–8706. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Studier F.W., Moffatt B.A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lavander M., Sundberg L., Forsberg A. Proteolytic cleavage of the FlhB homologue YscU of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for bacterial survival but not for type III secretion. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4500–4509. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4500-4509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.