Abstract

Objective:

Our paper presents findings from the first population survey of stigma in Canada using a new measure of stigma. Empirical objectives are to provide a descriptive profile of Canadian’s expectations that people will devalue and discriminate against someone with depression, and to explore the relation between experiences of being stigmatized in the year prior to the survey among people having been treated for a mental illness with a selected number of sociodemographic and mental health–related variables.

Method:

Data were collected by Statistics Canada using a rapid response format on a representative sample of Canadians (n = 10 389) during May and June of 2010. Public expectations of stigma and personal experiences of stigma in the subgroup receiving treatment for a mental illness were measured.

Results:

Over one-half of the sample endorsed 1 or more of the devaluation discrimination items, indicating that they believed Canadians would stigmatize someone with depression. The item most frequently endorsed concerned employers not considering an application from someone who has had depression. Over one-third of people who had received treatment in the year prior to the survey reported discrimination in 1 or more life domains. Experiences of discrimination were strongly associated with perceptions that Canadians would devalue someone with depression, younger age (12 to 15 years), and self-reported poor general mental health.

Conclusions:

The Mental Health Experiences Module reflects an important partnership between 2 national organizations that will help Canada fulfill its monitoring obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and provide a legacy to researchers and policy-makers who are interested in monitoring changes in stigma over time.

Keywords: stigma, stigma experiences, Devaluation Discrimination Scale, Opening Minds, Statistics Canada, Mental Health Experiences Module

Abstract

Objectif :

Notre article présente les résultats du premier sondage sur les stigmates dans la population du Canada, mené à l’aide d’une nouvelle mesure des stigmates. Les objectifs empiriques sont de fournir un profil descriptif des attentes des Canadiens, soit que les gens dévalorisent et exercent une discrimination à l’encontre d’une personne souffrant de dépression, et d’explorer la relation entre l’expérience d’être stigmatisé dans l’année précédant le sondage chez les gens qui ont été traités pour une maladie mentale, et un nombre choisi de variables sociodémographiques et liées à la santé mentale.

Méthode :

Les données ont été recueillies par Statistique Canada en utilisant un format de réponses rapides dans un échantillon représentatif des Canadiens (n = 10 389) en mai et juin 2010. Les attentes du public relativement aux stigmates et les expériences personnelles des stigmates dans le sous-groupe recevant un traitement pour une maladie mentale ont été mesurées.

Résultats :

Plus de la moitié de l’échantillon appuyait 1 ou plusieurs items de discrimination dévalorisante, indiquant qu’ils croyaient que les Canadiens stigmatiseraient une personne souffrant de dépression. L’item le plus fréquemment appuyé concernait les employeurs qui rejetaient une demande d’emploi d’une personne ayant fait une dépression. Plus du tiers des personnes ayant reçu un traitement dans l’année précédant le sondage ont déclaré faire l’objet de discrimination dans 1 ou plusieurs domaines de leur vie. Les expériences de discrimination étaient fortement associées aux perceptions que les Canadiens dévaloriseraient une personne souffrant de dépression, les jeunes (de 12 à 15 ans), et une santé mentale générale médiocre auto-déclarée.

Conclusions :

Le module des expériences de santé mentale reflète un important partenariat entre 2 organisations nationales qui aideront le Canada à s’acquitter de ses obligations de surveillance en vertu de la Convention des Nations Unies relative aux droits des personnes handicapées et à offrir un héritage aux chercheurs et décideurs qui s’emploient à observer les changements dans la stigmatisation avec le temps.

Contemporary disability discourse, which has culminated in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,1 recognizes that social environments create disability through discrimination, social oppression, and social inequity. Signatories to the Convention (and Canada is one) agree to undertake activities to remove harmful stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminatory practices.2 In response to this and the growing public health interest in mental illness–related stigma, many countries have mounted large anti-stigma efforts.

Demonstrating the effectiveness of these programs is challenging and requires population-based data. Statistics Canada regularly collects population-based data to monitor the health status and mental health status of Canadians, but has not had detailed information on stigma. In 2008, members of the OM Anti-Stigma Initiative and Statistics Canada addressed this gap. Our paper presents findings from the first national survey of stigma. Empirical objectives are 1) to describe Canadian’s expectations that people will devalue and discriminate against someone with depression, providing a community-based index of stigmatization, and 2) to explore the relation between the experience of being stigmatized among people who have been treated for a mental illness, and selected sociodemographic and mental health-related variables.

Methods

The Stigma Modules

The stigma modules measure public attitudes toward people with a mental illness (depression), and personal experiences of discrimination reported by recent service users. Two existing scales were adapted to fit the 3-minute window allowable within the survey. Modifications were done with the permission of the authors, and Statistics Canada staff tested the modified scales extensively using qualitative and quantitative methods.

Clinical Implications

Canadians expect that people with depression are more likely to experience discrimination, rather than devaluation; therefore, it is important that anti-stigma programs focus on discriminatory behaviours.

As youth (aged 12 to 25 years) are more likely to report experiences of discrimination, it is important that anti-stigma programs target this group.

As employers are expected to discriminate against people with depression, it is important to consider anti-stigma programming for employers and workplaces.

Limitations

Qualitative testing showed that Canadians may be uncomfortable estimating how others would react to people with depression. This might have resulted in underestimates of public stigma.

The small sample of people who had been treated in the previous year and had experienced discrimination prevented a robust analysis of associations.

The optional content in the annual component in the CCHS meant that many variables of interest could not be included in the analysis because they had not been collected uniformly across all provinces.

The first scale—The Devaluation–Discrimination Scale— was developed by Link.3 It asks respondents to indicate whether they think most people would devalue (think less of) or discriminate against someone who had been treated for a mental illness. This approach is superior to one that directly asks respondents to report their personal biases and prejudices, which engender socially acceptable responses. Depression was chosen as the frame because it is one of the key disorders assessed by the CCHS. Depression was defined for respondents as “a prolonged period of sadness or loss of interest in usual activities that interferes with daily life.” The original 12-item scale was shortened to 6 items: most people you know would not be willing to accept someone who has had depression as a close friend (discrimination); most people you know believe that someone who has had depression is not trustworthy (devaluation); most people you know think less of a person who has had depression (devaluation); most employers would not consider an application from someone who has had depression (discrimination); most people you know would be reluctant to date someone who has had depression (discrimination); and, once they know a person has had depression, most people you know would take their opinions less seriously (devaluation). Items were scored on a 5-point agreement scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, with a possible range of 6 to 35. Higher scores reflect higher levels of stigma. The internal consistency of the scale in this sample was high (0.82).

The second scale came from The Inventory of Stigma Experiences, which includes a subscale to assess the frequency of occurrence and psychosocial impact of stigma across key life domains. The Inventory of Stigma Experiences targets people with a mental disorder who have received community-based treatment.4 The modified version (now termed the Mental Health Experiences Scale) assesses levels of stigma experienced by people who have been treated for a mental illness in the year prior to the survey. This period was chosen (for example, over a lifetime prevalence measure) so that successive surveys could monitor change over time. Stigma was defined for respondents as a feeling that someone held “negative opinions about you or treated you unfairly because of your past or current emotional or mental health problem.” If respondents answered yes, they were asked to rate how this affected them on a scale of 0 (meaning they had not been affected) to 10 (meaning they had been severely affected) across 5 life domains: family relationships, romantic life, school or work life, financial situation, and housing situation. The aggregated scale ranges from 0 to 50, with higher scores reflecting higher personal impact. Cronbach alpha in this sample was high (0.90).

This analysis also included sex, age group (12 to 25 years, 26 to 55 years, or ≥56 years), education (<secondary, secondary, or college or university), income group (≤$19 999, $20 000 to $39 999, $40 000 to $59 999, $60 000 to $79 999, $80 000 to $99 999, or ≥$100 000), general mental health (excellent or very good, good, fair or poor), and personal contact with someone who has a mental illness (work colleague, close friend, close family member, or self). These were the only variables of interest collected across all provinces.

Data Collection

In 2010, OM funded a rapid response survey through Statistics Canada using the new modules (n = 10 389). Rapid response surveys piggyback new content onto a 2-week collection window of the annual portion of the CCHS. The CCHS is a multi-stage, cross-sectional survey of about 65 000 respondents aged 12 and older. About 3% of the population (people living on reserves, institutionalized, or full-time members of the Canadian Forces) are excluded from the sampling frame. The rapid response portion that included the stigma scales was conducted in May and June of 2010. Details on the data collection methods used in the CCHS can be found on the Statistics Canada website.5 The CCHS has a response rate of 72.3%.6 The analysis received ethics clearance from the Queen’s University and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board.

Data Analysis

In accordance with Statistics Canada quality guidelines, all analyses were weighted and variance estimates bootstrapped (n = 500). We report the weighted per cent and the CV; the proportion of each parameter estimate that is attributable to sampling variation is expressed as a percentage (100 × standard error of the parameter estimate / parameter estimate). CVs greater than 16.6% are unreliable and presented with a cautionary flag. The Mental Health Experiences scale was bimodally distributed. Therefore, we dichotomized it to reflect the presence or absence of stigma and used logistic regression to explore the relations of sociodemographic and mental illness–related factors to experiences of stigma. Because we encountered problems with model convergence, 2 variables (income and contact with a close friend) were omitted from the analysis.

Results

Devaluation and Discrimination

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics and the descriptive results of the Devaluation–Discrimination Scale by sex. Only 1 estimate (females making ≥$100 000; CV = 19.6%) was unreliable. Ages ranged from 12 to 101. One-half of the sample was between the ages of 26 and 55 years, and the majority (82%) had a college- or university-level education. There were no sex differences. Personal income categories ranged from less than $20 000 to over $100 000 per year, with 67.9% of men and 86.4% of women making less than $60 000 per year. A greater proportion of women were in the lowest income categories. Three-quarters of the sample reported their general mental health to be excellent or very good, with less than 1 in 10 (about 6%) indicating their mental health was fair or poor. Twice as many women as men reported having received treatment for a mental illness (22%, compared with 11%, respectively). Women were also more likely to report that they had a work colleague, a close family member, or a close friend who had received treatment for a mental illness.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and Devaluation–Discrimination Scale items, weighted per cent (coefficient of variation), n = 10 389

| Characteristic | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 12–25 | 21.6 (1.9) | 20.6 (1.8) | 21.0 (1.2) |

| 26–55 | 50.6 (1.7) | 50.6 (1.4) | 50.6 (1.1) |

| 56–101 | 27.8 (2.7) | 28.9 (2.2) | 28.3 (1.7) |

| Highest education | |||

| Primary | 7.6 (0.8) | 7.7 (5.8) | 7.7 (5.1) |

| Secondary | 10.4 (7.5) | 11.3 (6.4) | 10.8 (4.8) |

| College or university | 82.0 (1.1) | 81.0 (1.0) | 81.5 (0.8) |

| Personal yearly income, $ | |||

| ≤19 999 | 20.0 (5.2) | 36.0 (3.9) | 27.7 (3.3) |

| 20 000 to 39 999 | 26.7 (4.9) | 33.0 (4.4) | 29.8 (3.4) |

| 40 000 to 59 999 | 21.2 (5.9) | 17.4 (6.4) | 19.3 (4.2) |

| 60 000 to 79 999 | 15.3 (7.2) | 7.9 (10.0) | 11.7 (5.9) |

| 80 000 to 99 999 | 6.4 (10.4) | 3.6 (15.3) | 5.1 (8.5) |

| ≥100 000 | 10.4 (9.6) | 2.1 (19.6)a | 6.4 (8.7) |

| General mental health | |||

| Excellent or very good | 74.8 (1.4) | 72.3 (1.4) | 73.5 (1.0) |

| Good | 19.8 (4.6) | 21.5 (4.4) | 20.7 (3.1) |

| Fair or poor | 5.5 (9.5) | 6.2 (8.7) | 5.8 (5.8) |

| Prior contact with someone who has been treated for a mental illness | |||

| Worked or volunteered in program | 10.1 (6.4) | 17.4 (4.1) | 13.8 (3.6) |

| Work colleague who received treatment for a mental illness | 36.2 (3.2) | 41.4 (2.7) | 38.8 (2.1) |

| Close member of family received treatment for a mental illness | 33.6 (3.6) | 40.0 (2.6) | 36.8 (2.2) |

| Close friends received treatment for a mental illness | 28.7 (3.6) | 40.0 (2.7) | 34.5 (2.2) |

| Devaluation–Discrimination Scale items (strongly agree or agree) | |||

| Most people you know would not willingly accept someone who has had depression as a close friend. | 19.9 (4.9) | 20.1 (4.7) | 20.0 (3.4) |

| Most people you know would believe that someone who has had depression is not trustworthy. | 11.8 (6.8) | 9.3 (7.2) | 10.5 (4.8) |

| Most people you know would think less of a person who has had depression. | 19.6 (4.6) | 19.8 (4.6) | 19.7 (3.4) |

| Most employers would not consider an application from someone who has had depression. | 38.7 (2.8) | 37.7 (3.0) | 38.2 (2.1) |

| Most people you know would be reluctant to date someone with depression. | 34.2 (3.2) | 33.2 (3.1) | 33.7 (2.3) |

| Once they know a person has had depression, most people you know would take their opinions less seriously. | 26.3 (3.9) | 23.1 (4.2) | 24.7 (2.9) |

| Cumulative count of Devaluation–Discrimination Scale items | |||

| 0 endorsed | 41.7 (2.9) | 42.3 (2.8) | 41.8 (2.1) |

| 1 endorsed | 20.7 (4.8) | 21.9 (4.7) | 21.3 (3.2) |

| 2 endorsed | 12.6 (6.7) | 13.2 (5.7) | 12.9 (4.2) |

| 3 endorsed | 10.2 (7.9) | 8.2 (7.9) | 9.2 (5.6) |

| 4 endorsed | 6.3 (10.0) | 7.1 (9.0) | 6.7 (7.1) |

| 5 endorsed | 4.7 (11.9) | 4.1 (12.0) | 4.4 (8.4) |

| 6 endorsed | 4.3 (13.3) | 3.1 (13.1) | 3.7 (9.4) |

| Have received treatment for a mental illness | 11.2 (6.2) | 21.6 (4.2) | 16.5 (3.4) |

|

| |||

| Mental Health Experiences Scale, n = 752 | |||

|

| |||

| Experience of discrimination in 1 or more life domains, a score of 1 to 10 | 40.2 (9.4) | 36.1 (9.3) | 37.4 (7.9) |

Interpret with caution owing to a large coefficient of variation

More than one-half of the sample (about 58%) endorsed at least 1 Devaluation–Discrimination Scale item, most frequently the item pertaining to employers. Over one-third of Canadians (38.2%) considered that employers would discriminate against someone who has had depression. Similarly, one-third (33.7%) indicated that most people they know would be reluctant to date someone with depression. The least endorsed item (10.5%) was that people would believe someone who has had depression was not trustworthy. Though not shown on the table, 59.3% of the sample indicated that they shared these opinions, 14.3% were neutral, and 26.4% disagreed.

Mental Health Experiences

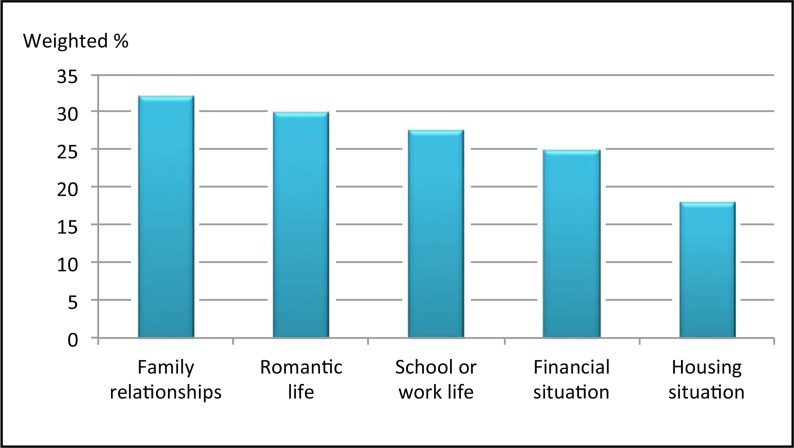

One-third (38.5%) of people treated for a mental illness in the past year indicated they had been treated unfairly because of a current or past mental health or emotional problem, most frequently in relation to intimate personal relationships, such as family (32%) or romantic relationships (30%). Stigma was also experienced in school or work (28%) and finances (25%) but to a slightly lesser degree. Housing was the area least affected by stigma in this sample (18%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Twelve-month stigma impact

Table 2 shows that 3 variables were significant predictors of stigma experiences: the Devaluation–Discrimination Scale, age group, and general mental health. Each unit change in the Devaluation–Discrimination Scale was associated with a 20% increase in the likelihood of having experienced stigma. The likelihood of experiencing stigma decreased with age group in a dose–response pattern. Finally, people who rated their general mental health as fair or poor were almost 3 times more likely to have experienced stigma. The remaining variables were not significant.

Table 2.

Multivariate regression of mental health experiences of stigma

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devaluation–Discrimination Scale | 1.2 | 1.1 to 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | — | — | — |

| Female | 0.79 | 0.43 to 1.5 | 0.44 |

| Age, years | |||

| 12–25 | — | — | — |

| 26–55 | 0.28 | 0.12 to 0.61 | 0.002 |

| 56–101 | 0.16 | 0.06 to 0.41 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||

| Primary | — | — | — |

| Secondary | 0.86 | 0.25 to 3.0 | 0.81 |

| College or university | 0.64 | 0.25 to 1.7 | 0.36 |

| General mental health | |||

| Excellent or very good | — | — | — |

| Good | 1.2 | 0.5 to 2.8 | 0.68 |

| Fair or poor | 2.8 | 1.2 to 6.7 | 0.02 |

| Worked or volunteered in a program | |||

| No | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1.8 | 0.84 to 3.7 | 0.13 |

| Worked with a colleague | |||

| No | — | — | — |

| Yes | 0.74 | 0.37 to 1.5 | 0.4 |

| Contact with close family member | |||

| No | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1 | 0.54 to 2.1 | 0.89 |

| Do you share opinions on the Devaluation–Discrimination Scale | |||

| Agree | — | — | — |

| Neutral | 1.2 | 0.39 to 3.6 | 0.76 |

| Disagree | 1.3 | 0.62 to 2.7 | 0.49 |

Income and contact with a close friend were omitted from the model to allow it to converge. Unstable estimates can result when variables are collinear with other variables in the model.

— = Reference

Discussion

Our paper presents the results of a rapid response survey, examining 2 aspects of stigma—the extent to which respondents believe that most Canadians would devalue or discriminate against someone with depression, and the extent to which people who have been treated for a mental illness in the previous year have experienced stigma in 1 or more life domains. These are the first population-based data describing stigma in Canada, and this is the first ever population-based study describing personal stigma experienced among people treated for a mental illness. Over one-half of the sample believed Canadians would devalue or discriminate against someone with depression. The item most frequently endorsed concerned employers not considering an application from someone who has had depression. Over one-third of people who had received treatment in the year prior to the survey reported discrimination in 1 or more life domains. Experiences of discrimination were strongly associated with perceptions that Canadians would devalue someone with depression, younger age group (12 to 15 years), and self-reported poor mental health.

It is interesting that the items referring to devaluation were less frequently endorsed than discrimination items. For example, respondents indicated that people with depression would be taken less seriously (24.7%), would be thought less of (19.7%), and would be seen as less trustworthy (10.5%)—items pertaining to devaluation. Conversely, they expected that employers would not consider an application from someone with depression (38.2%), that most people would not date someone with depression (33.7%), or that most people would not willingly accept someone who has depression as a close friend (20.0%)—items pertaining to discrimination. These findings highlight the importance of OM targeting stigmatizing behaviours (as opposed to attitudes), particularly among employers and in workplaces.

People who have been personally stigmatized were more likely to expect others to be stigmatizing. This is consistent with the “why try” effect,7 which occurs when people with a mental illness expect to be stigmatized, internalize pernicious social stereotypes related to devaluation and discrimination, and lower their expectations related to the achievement of 1 or more life goals. Results also showed a distinctive age gradient, where youth aged 12 to 25 reported the highest level of personal stigma in the year prior to the survey. These results support the importance of targeting youth for anti-stigma programming and suggest that interventions targeting self-stigma should target people who are early in the course of their illness and recovery. Because most mental disorders begin in adolescence or early adulthood, stigma experienced during this time may be more frequent or more impactful. Over time, people recover and learn how to manage or move beyond the stigma.8 Longitudinal research following people from their first episode of illness over time would be required to examine this issue more comprehensively.

The lack of association between the personal contact variables and stigma experiences was unexpected as social contact theory predicts that positive interpersonal contact reduces stigmatizing views.9 Contact-based education has become one of the most promising practices in the field of anti-stigma intervention10 and one that is central to the OM approach to stigma reduction.11,12 However, note that interpersonal contact is typically directed toward reducing public stigma, not personal experiences of stigma. Our findings indicate that the odds of being stigmatized are similar, whether or not one has had contact with people with a mental illness.

The development of the Mental Health Experiences Module reflects an important partnership between 2 national organizations that will help Canada fulfill its monitoring obligations under the United Nations Convention and provide a legacy to researchers and policy-makers who are interested in monitoring changes in stigma over time.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded as a collaborative effort between the OM Anti-Stigma Initiative of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) and Statistics Canada. This supplement was funded by the MHCC, which is funded by Health Canada, and by the Bell Canada Mental Health and Anti-Stigma Research Chair at Queen’s University. Dr Patten is a Senior Health Scholar with Alberta Innovates, Health Solutions. The views expressed in this report represent the perspectives of the authors.

Abbreviations

- CCHS

Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-Being

- CV

coefficient of variation

- OM

Opening Minds

References

- 1.United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) Geneva (CH): United Nations; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J. A public health perspective on the stigmatization of mental illnesses. Public Health Rev. 2012;34(2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link B. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52(1):96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart H, Koller M, Milev R. Inventories to measure the scope and impact of stigma experiences from the perspective of those who are stigmatized—family and consumer versions. In: Arboleda-Flórez J, Sartorius N, editors. Understanding the stigma of mental illness Theory and interventions. Chichester (GB): John Wiley and Sons; 2008. pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey—annual component (CCHS) [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2012. [cited 2014 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226&Item_Id=144171$lang=en. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)—annual component user guide 2010 and 2009–2010 microdata files (Appendix G) [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2011. [cited 2014 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/3226_D7_T9-V8-eng.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corrigan P, Larson J, Rusch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amering M, Schmolke M. Recovery in mental health. Oxford (GB): Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couture S, Penn D. Interpersonal contact and the stigma of mental illness: a review of the literature. J Ment Health. 2003;12(3):291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrigan P, Morris S, Michaels P, et al. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):963–973. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patten S, Remillard A, Phillips L, et al. Effectiveness of contact-based education for reducing mental illness-related stigma in pharmacy students. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart H, Koller M, Christie R, et al. Reducing mental health stigma: a case study. Healthc Q. 2011;14 doi: 10.12927/hcq.2011.22362. Spec No: 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]