Abstract

Purpose: The aim of present study was to determine effects of L-Arginine supplementation on antioxidant status and body composition in obese patients with prediabetes.

Methods: A double-blind randomized control trial was performed on 46 (24 men, 22 women) obese patients with prediabetes. They were divided randomly into two groups. Patients in intervention (n = 23) and control group (n=23) received 3 gr/day L-arginine and placebo, respectively for 8 weeks. Anthropometric indices, dietary intake and biochemical measurements ((serum total antioxidant capacity (TAC), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)) were performed at the baseline and after 8-week intervention.

Results: The mean age and BMI of participants were 44.29±8.65 years old and 28.14±1.35 kg/m2, respectively. At the end of study, in both intervention and control group, percentage of carbohydrate decreased and %fat intake increased compared to the baseline (P<0.05). After adjusting for dietary intake, no significant difference was observed in Fat Mass (FM) and Fat Free Mass (FFM) between two groups (P>0.05). Among measured biochemical factors, only serum TAC level showed significant differences at the end of study in the intervention group compared to the control group (pv<0.01).

Conclusion: 3gr/day L-Arginine supplementation increased TAC level in obese patients with prediabetes.

Keywords: L-arginine, Prevention, Oxidative Stress, Prediabetes

Introduction

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder that is increasing in the world. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) has predicted that the prevalence of diabetes will increase from 135 million in 1995 to 300 million in 2025.1 DM can increase risk of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia and mortality. When Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) is above the normal range (100-125 mg/dl) but not high enough for diagnosis of DM, it named as prediabetes.2 Prevalence of prediabetes in the world is not available, but possibility it is greater than prevalence of diabetes. Uncontrolled blood glucose level in subjects with prediabetes can lead to type 2 DM and its complications.3 Therefore, treatment of patients with prediabetes can minimize cost, required health resources, diabetes complications and can improve quality of life.4 One of the main reasons for progression of diabetes and its complications is reduced activity of antioxidant defenses and high level of free radical production.5

Rising free radicals can increase protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation and plasma Nitric Oxide (NO) levels. Antioxidant ingredients can transfer electrons to oxidizing agents, so they inhibit from free radical production and cell damages.5,6Antioxidants can be classified into two groups: enzymatic (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase,…) and non-enzimatic agents (carotenoids, coenzyme Q10, some vitamins and minerals, Arginine,etc).7

L-Arg is a semi-essential amino acid that participates in protein and creatine synthesis, anabolic hormone simulation and nitrogen balance improvement.8 It is free radical scavenger and substrate of NO synthase, so it can alleviate and protect from endothelial damages. Some previous studies indicated that L-Arg is protective agent against some chronic diseases.9,10 Tripati and Misra demonstrated that L-Arg supplementation increased some antioxidant enzyme activities in patients with ischemic heart disease.11 In Lucotti et al study, concurrent L-Arg supplementation with hypocaloric diet and exercise training, improved endothelial function and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes.12 Piattee et al reported that potential mechanism for improving peripheral and hepatic insulin sensivity by L-Arg administration may be due to the effect of L-Arg on NO synthesis.13Although there are strong evidences about antioxidant and preventive roles of L-Arg amino acid for some chronic diseases, but it seems that there are limited studies on antioxidant role of L-Arg amino acid in patients with prediabetes.

Considering rising prevalence of diabetes, heavy cost of diabetes treatment and limited studies, the primary aim of present study was to determine the effect of L-Arginine supplementation on antioxidant status in obese patients with prediabetes and the secondary aim was to determine effects of L-Arg supplementation on antioxidant status and body composition in obese patients with prediabetes.

Materials and Methods

Study design

In this double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial, 46 patients (24 men, 22 women) with prediabetes that referred to Endocrine Research Center of Shariati hospital in Tehran were recruited. Based on Jableka et al14 and TAC variable, sample size was calculated with α-value 0.05 and power 80%. With dropout rate of 20%, sample size increased to 23 subjects in each study group. Patients were recruited through physician referral from October 2012 to February 2013. Inclusion criteria were as follows: both sexes, age 20-50 yrs, recently diagnosed patients, FBS between 100 to 125mg/dl or 2-hour postprandial blood sugar 140-199 mg/dl and Body Mass Index (BMI) 25-34.9 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria were as follows: cardiovascular disease, liver and kidney diseases, thyroid disorders, smoking, taking vitamin/ mineral supplements, pregnancy and lactation.

After completing informed consent by eligible patients, they were adjusted for age, sex and BMI. Thereafter subjects were assigned to the intervention or placebo group by random number table and permuted blocks of size 2. Patients in intervention and placebo group took 3 gr L-Arg supplement (Karen Pharma & Food Supplement Co. Iran) and maltdextrin (1000 mg capsules) 3 times a day (once every 8 hours), respectively for eight weeks. L-Arg and maltodextrin capsules had the same size and color. Researcher and patients did not know which capsule was being used. Also participants were asked not to change their diet and physical activity during the study. They were follow-up every 2 weeks for receiving supplements and any possible side effects of taking L-Arg supplements.

Assessments

Basal characteristic questionnaire was filled out with face to face interview. Anthropometric indices, body composition, dietary intake, physical activity and biochemical measurements were performed at the baseline and after 8-week intervention.

Anthropometric and body composition measurements :

Patients were weighed in light clothing without shoes. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a wall-mounted stadiometer while subjects were standing without shoes with shoulders in a standard position. BMI was calculated with division weight in kilograms into the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Body composition (Fat Mass (FM) and Fat Free Mass (FFM)) was meseared by bioelectrical impedance analysis (TANITA BC-418, Co. Tokyo).

Dietary and physical activity Assessments :

24-h dietary record (2 work days and 1 weekend) were filled out by patients at the baseline and the end of study for dietary assessment. Physical activity level was determined by International Physical activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) with face to face interview at the baseline and after 8- week intervention.

Biochemical measurements :

After 12-14 hour fasting, 7 cc venous blood samples of patients were collected. Blood samples were centrifuged and serum separated. Serum samples were stored at -70 °C until biochemical measurements. Concentration of serum Superoxidase Dismutase (SOD) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) were measured using commercial kit (Cayman Chemical®, Michigan, USA) by spectrophotometer and Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) were meseared by FRAP (Fluorescence recovery after photo bleaching) method at the baseline and the end of study.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were recorded in percentage and Mean±SD, respectively. Normality distribution of data was determined by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For normally distributed data, independent t-test and paired t-test were applied for comparison between two groups and within each group, respectively. But for non-normally distributed data, Mann-Whitney U-test and Wilcoxan were used for comparison between two groups and within each group, respectively. For adjusting confounder factors, ANCOVA test was applied. For dietary intake analysis Nutritionist IV program was used. All statistical analysis was performed by SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). P-value<0.05 considered significant.

Results

Basal characteristic of participants

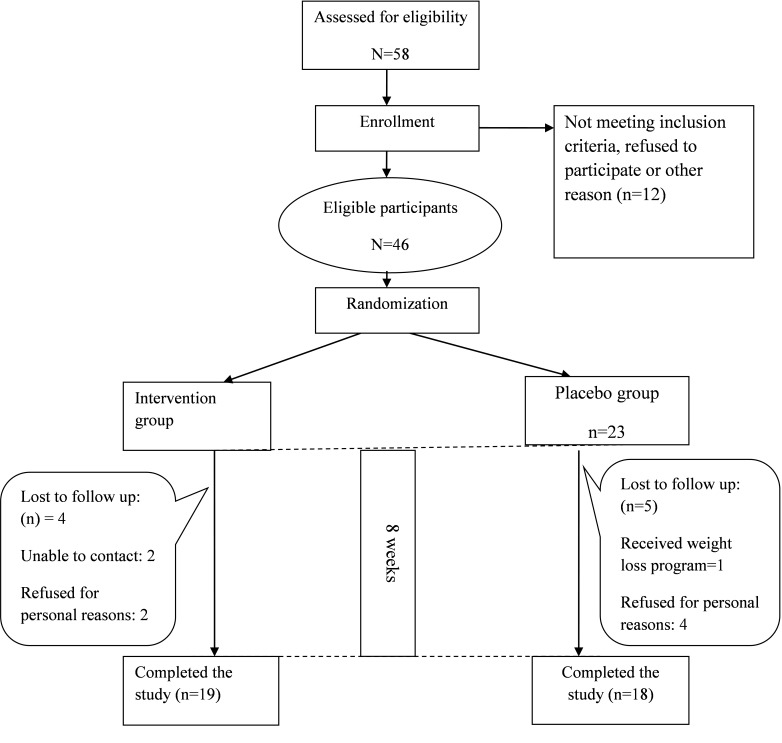

In the present study, 46 eligible subjects (24 men, 22 women) with the mean age of 44.29±8.65 years were recruited. Finally 37 subjects (19=intervention; 18=control) were completed the study (Figure 1). No side effects were reported during the intervention by participants. No significant differences was observed in mean of age, sex and education level between two groups (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm of participants in two groups during the intervention

Table 1. Basal characteristic of participants in two groups.

| Variable | Intervention (n=23) | Placebo (n=23) | **P-value | |

| Age(years) | 40.34±3.77a | 38.6±5.39 | 0.21† | |

| Sex (%) | Men | 57.9 | 57.9 | 0.9* |

| Women | 42.1 | 42.1 | ||

| Education(%) | Primary/high School | 15.8 | 26.3 | 0.05‡ |

| Diploma | 63.2 | 21.1 | ||

| University education | 15.8 | 26.3 | ||

| Physical activity level (%) | Sedentary | 83 | 79 | 0.72* |

| Moderate | 17 | 21 | ||

a Mean±SD, †: Independent t-test, *:K Square test, ‡: Exact, Fisher test, **p<0.05 considered significant

Dietary intake and physical activity assessment

Comparison total energy intake, carbohydrate, protein and dietary Arg between two groups showed no significant differences at the baseline. But there was a significant difference in %fat intake between two groups at the baseline (p=0.04).Within both intervention and control group, percentage of carbohydrate decreased and %fat increased compared to the baseline. Dietary Arg intake, …. Monounsaturated Fatty Acid (MUFA) and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) in control group increased at the end of study (Table 2). 83 and 79% of subjects in intervention and control group reported sedentary physical activity, respectively (Table 1). Physical activity level in both groups did not change during the study (p>0.05).

Table 2. Comparison of dietary intake in intervention and control group at the baseline and the end of study.

| Variable | Intervention (n=23) | Placebo (n=23) | *P value | **P value | |||

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | ||||

| Energy | 2293 ±941 | 2341.1±386.9 | 2033±665.6 | 2198.6±499.2 | 0.61 | 0.33 | |

| Carbohydrate | (gr) | 301.5±110.3 | 273.5±45.7 | 286.8±89.1 | 279±68.7 | 0.90 | 0.77 |

| % | 52.8±6.2 | 46.85±5.4 | 56.8±8.0 | 49.3±4.7 | 0.15 | 0.14 | |

| Protein | (gr) | 66.8±22.9 | 76.6±12.8 | 73±29.6 | 74.4±17.5 | 0.48 | 0.65 |

| % | 12.1±3.7 | 13.1±2.1 | 14±3.59 | 13.3±1.5 | 0.13 | 0.75 | |

| Fat | (gr) | 94.8±54.5 | 107.8±32.0 | 68.7±31.1 | 90.5±26.8† | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| % | 34.2±7.0 | 39.8±5.95 | 29.2±6.9 | 37.1±4.48 | 0.04† | 0.12‡ | |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 212.2±165.1 | 281.5±110.1 | 225.4±157.1 | 250.1±85.5 | 0.62 | 0.35 | |

| SFA (gr)1 | 25.0±15.1 | 28.6±11.6 | 26.1±23.7 | 26.2±11.4 | 0.71 | 0.52 | |

| MUFA (gr)2 | 38.9±25.6 | 44.7±13.4 | 29.3±14.9 | 36.5±10.9 | 0.18 | 0.04† | |

| PUFA (gr)3 | 24.9±18.81 | 28.3±11.5 | 15.1±7.2 | 22.4±9.0 | 0.02† | 0.08‡ | |

| Dietary Arg (mg) | 922.4±591.8 | 587.7±254.2 | 635.2±383.8 | 654.8±318.7 | 0.08 | 0.47 | |

‡ ANCOVA, †p<0.05 considered significant, 1Saturated Fatty Acid, 2Monounsaturated Fatty Acid, 3Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid,

*: comparision two groups at the baseline, **: comparision two groups at the end of the study

Anthropometric and body composition measurements

Due to adjusting subjects for BMI at the baseline, no significant difference between two groups was observed in BMI value (P>0.05). Body composition between two groups did not show significant difference at the baseline. But in the intervention group, FM and FFM indicated significant difference compared to the baseline. After adjusting for confounder factors (PUFA, MUFA, percent of dietary fat intake), body composition and weight showed no significant changes at the end of the trial (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of anthropometric indices and body composition of patients at the baseline and the end of study.

| Variable | Intervention (n=23) | Placebo (n=23) | †P value | *P value | ||

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | |||

| Weight (Kg) | 75.69 ±8.32 | 74.91±8.36 | 79.12±10.73 | 78.86±11.48 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.70±1.40 | 27.40±1.49 | 28.58±1.31 | 28.48±1.56 | 0.05 | 0.41 |

| FM (%) | 27.99±7.42 | 26.56±7.57† | 30.66±8.39 | 30.13±8.22 | 0.31 | 0.15 |

| FFM (%) | 72.01±7.42 | 73.44±7.57† | 69.34±8.39 | 69.89±8.24 | 0.31 | 0.16 |

† Independent t-test: comparision to groups at the base line , *ANCOVA: comparison two groups at the end of study

Biochemical tests

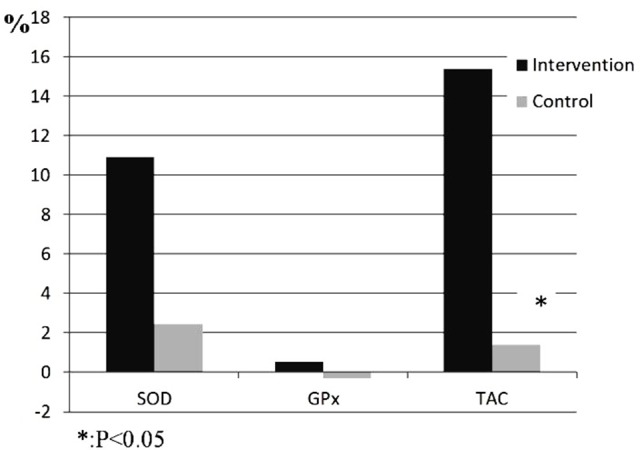

No significant differences were observed in serum SOD, GPx and TAC levels at the baseline between two groups (Table 4). After adjusting for dietary Arg, PUFA and percentage of fat at the end of study, only serum TAC level showed a significant difference at the end of study in intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.01). Percentage of changes in SOD, GPx and TAC levels for intervention group was 10.92, 0.51 and 15.38%, respectively (Figure 2).

Table 4. Comparison of biochemical parameters in participants at the baseline and the end of study.

| Variable | Intervention (n=23) | Placebo (n=23) | †P value | *P value | ||

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | |||

| SOD (U/L) | 77.1±12.3 | 85.5±18.4 | 76.62±14.94 | 78.52±16.97 | 0.8 | 0.05 |

| GPx (U/ml) | 126.9±10.1 | 127.6±9.8 | 1.43±0.36 | 1.45±0.37 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| TAC (mmol/l) | 1.3±0.1 | 1.5±0.3† | 1.43±0.36 | 1.45±0.37 | 0.17 | <0.01 |

† t-test: comparison two groups at the baseline, *ANCOVA: comparison two groups at the end of study

Figure 2.

The percentage changes in biochemical parameters for two groups during the intervention

Discussion

Some previous experimental and clinical studies indicated that L-Arg amino acid can improve antioxidant status.11,12,14,15 In the present study, supplementation with 3gr/day L-Arg increased TAC level in patients with prediabetes after 8 weeks. Previous studies have shown that fat aggregation is associated with oxidative stress in human and rats. ROS production in adipose tissue of obese rats increased NADPH oxidase and decreased antioxidant enzymes. Also FM is associate with free radicals.16-18 In the present study, increasing TAC may be due to decreasing of FM in intervention group. Although it was not significant, but a little decreasing of FM may help to decrease oxidative stress in study patients.

In this study, despite of increasing SOD level in intervention group at the end of study, it was not significant (P=0.05). It was in line with Tripati et al research. They indicated that supplementation with 3gr L-Arg in ischemic patients for 15 days increased SOD level, but its increasing was not significant.11 Also Huang et al reported that supplementation with L-Arg (2% of diet) increased antioxidant enzyme level, but it was not significant.19In Lucotti et al study 8.3 gr L-Arg concurrent with weight loss diet for 21 days increased SOD levels.12Different dose and weight loss diet besides taking L-Arg supplement is a possible reason for different results.

According to Missiry et al, injection of 100 mg/kg L-Arg in diabetic rats increased GSH,SOD and catalayse levels.20But in line with the present study, in Jabecka et al study, 2 gr L-Arg during 28 days increased TAC level in atheroscloric patients.12Also Ren et al concluded that after L-Arg supplementation, TAC level in rats with virus infection increased.15

In the present study, GPx level did not change significantly after intervention. The present study was in line with missiry el al20 and Kochar et al studies.21 In Kochar et al study, 100 mg/kg L-Arg supplementation in diabetic rats increased GSH and SOD levels.21

Previous studies indicated that NADH, NADPH and FADH2 production occur in aerobic pathway of protein, fat and glucose. High energy intake, increases free radical production in mitochondria. and it can increase oxidative stress.22By controlling diet intake and physical activity in the present study, these dietary factors cannot affect antioxidative enzymes and the other mechanisms may be responsible for these changes.

For future studies, larger sample size, longer intervention time and considering physiological stress of participants are suggested.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that 3gr/day L-Arg supplementation for 2 months increased TAC level without any significant changes in other measured antioxidant enzymes and body composition in patients with prediabetes. More studies are suggested to clarify the beneficial effects of L-Arg supplementation in patients with prediabetes for improvement of antioxidant status.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks all patients for participation in this study. We would also like to express my appreciation to Tehran University of medical sciences for their financial support and Endocrine Research Center of Shariati hospital for their cooperation with researchers. This article was written based on a data set for the MSc thesis of Siavash Fazelian that registered in Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical issues

Authors confirm the liability of the scientific integrity of the article contents. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and written informed consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of the study. The trial was registered on the Iranian registry of clinical trials website (URL: www.irct.IR) with Clinical trial number: IRCT201211106415N2.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P. et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, Eberhardt MS, Byrd-Holt DD, Li C. et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the USpopulation in 1988-1994 and 2005-2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):287–94. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes A. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):202–12. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent AM, Russell JW, Low P, Feldman EL. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(4):612–28. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB 3rd. Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2003;17(1):24–38. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A review on the role of antioxidants in the management of diabetes and its complications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(7):365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lass A, Suessenbacher A, Wolkart G, Mayer B, Brunner F. Functional and analytical evidence for scavenging of oxygen radicals by L-arginine. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61(5):1081–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu G, Bazer FW, Davis TA, Kim SW, Li P, Marc Rhoads J. et al. Arginine metabolism and nutrition in growth, health and disease. Amino Acids. 2009;37(1):153–68. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu G, Davis PK, Flynn NE, Knabe DA, Davidson JT. Endogenous synthesis of arginine plays an important role in maintaining arginine homeostasis in postweaning growing pigs. J Nutr. 1997;127(12):2342–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.12.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi P, Misra MK. Therapeutic role of L-arginine on free radical scavenging system in ischemic heart diseases. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2009;46(6):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucotti P, Setola E, Monti LD, Galluccio E, Costa S, Sandoli EP. et al. Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(5):E906–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piatti PM, Monti LD, Valsecchi G, Magni F, Setola E, Marchesi F. et al. Long-term oral L-arginine administration improves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):875–80. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabecka A, Ast J, Bogdaski P, Drozdowski M, Pawlak-Lemaska K, Cielewicz AR. et al. Oral L-arginine supplementation in patients with mild arterial hypertension and its effect on plasma level of asymmetric dimethylarginine, L-citruline, L-arginine and antioxidant status. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(12):1665–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren W, Yin Y, Liu G, Yu X, Li Y, Yang G. et al. Effect of dietary arginine supplementation on reproductive performance of mice with porcine circovirus type 2 infection. Amino Acids. 2012;42(6):2089–94. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0942-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y. et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1752–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Festa A, D'agostino R Jr, Williams K, Karter AJ, Mayer-Davis EJ, Tracy RP. et al. The relation of body fat mass and distribution to markers of chronic inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(10):1407–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinaiko AR, Steinberger J, Moran A, Prineas RJ, Vessby B, Basu S. et al. Relation of body mass index and insulin resistance to cardiovascular risk factors, inflammatory factors, and oxidative stress during adolescence. Circulation. 2005;111(15):1985–91. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161837.23846.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CC, Lin TJ, Lu YF, Chen CC, Huang CY, Lin WT. Protective effects of L-arginine supplementation against exhaustive exercise-induced oxidative stress in young rat tissues. Chin J Physiol. 2009;52(5):306–15. doi: 10.4077/cjp.2009.amh068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Missiry MA, Othman AI, Amer MA. L-Arginine ameliorates oxidative stress in alloxan-induced experimental diabetes mellitus. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24(2):93–7. doi: 10.1002/jat.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochar NI, Umathe SN. Beneficial effects of L-arginine against diabetes-induced oxidative stress in gastrointestinal tissues in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(4):665–72. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327(6122):524–6. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]