Abstract

Background

As health care workers face a wide range of psychosocial stressors, they are at a high risk of developing burnout syndrome, which in turn may affect hospital outcomes such as the quality and safety of provided care. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the moderating effect of job control on the relationship between workload and burnout.

Methods

A total of 352 hospital workers from five Italian public hospitals completed a self-administered questionnaire that was used to measure exhaustion, cynicism, job control, and workload. Data were collected in 2013.

Results

In contrast to previous studies, the results of this study supported the moderation effect of job control on the relationship between workload and exhaustion. Furthermore, the results found support for the sequential link from exhaustion to cynicism.

Conclusion

This study showed the importance for hospital managers to carry out management practices that promote job control and provide employees with job resources, in order to reduce the burnout risk.

Keywords: burnout, cynicism, exhaustion, job control, workload

1. Introduction

Stress in the workplace is globally considered a risk factor for workers' health and safety. More specifically, the health care sector is a constantly changing environment, and the working conditions in hospitals are increasingly becoming demanding and stressful. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “a healthy workplace is one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process to protect and promote the health, safety and well-being of all workers and the sustainability of workplace [...]” [1]. Despite WHO's aim to promote and foster healthy work environments, approximately 2 million work-related deaths occurred in 2000 [2]. Several studies focusing on the health care sector have shown that health care professionals are exposed to a variety of severe occupational stressors, such as time pressure, low social support at work, a high workload, uncertainty concerning patient treatment, and predisposition to emotional responses due to exposure to suffering and dying patients [3,4]. In this sense, health care workers are at a high risk of experiencing severe distress, burnout, and both mental and physical illness. In turn, this could affect hospital outcomes, such as the quality of care provided by such institutions [4–7]. Particularly, in the past 35 years, the prevalence of stress-related illnesses such as burnout has increased significantly, affecting 19–30% of employees in the general working population globally [8]. Burnout among health care workers, mainly medical staff, was becoming an occupational hazard, with its rate reaching between 25% and 75% in some clinical specialties [9]. Furthermore, it was reported that among the sources of occupational illnesses, burnout represents 8% of the cases of occupational illnesses [10].

As defined by Leiter and Maslach [11] and Maslach [12], burnout is a cumulative negative reaction to constant occupational stressors relating to the misfit between workers and their designated jobs. In this sense, burnout is a psychological syndrome of chronic exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy, and is experienced as a prolonged response to chronic stressors in the workplace [13]. Exhaustion is mainly related to an individual's experience of stress, which is, in turn, related to a decline in emotional and physical resources. According to Leiter and Maslach [14], “the experience of exhaustion reduces workers' initiative while progressively limiting their capacity for demanding work” (p. 50). Cynicism refers to detachment from work in reaction to the overload of exhaustion [13]. Cynicism pertains to the loss of enthusiasm and passion for one's work [14]. The third component, perceived professional inefficacy, refers to the feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of achievement and productivity at work; in other words, perceived professional inefficacy refers to the loss of confidence in one's work [14]. Particularly, Maslach et al [15] hypothesized that three dimensions of burnout develop as a result of varying sequential progression over time. Previous research on burnout has confirmed the sequential link from exhaustion to cynicism [15]. Specifically, researchers have found “that exhaustion occurs first, leading to the development of cynicism, which in turn leads to inefficacy. However, the subsequent link to inefficacy is less clear, with the current data supporting a simultaneous development of this third dimension rather than a sequential one” [15] (p. 406).

Job burnout has been associated with a multiplicity of health problems, such as hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders, and sleeplessness [15]. It has also been associated with performance-related issues [16], demonstrating its direct impact on workplace effectiveness.

Regarding the etiology of burnout, researchers have mainly focused on the role played by an occupational context. Maslach and Leiter [17] provided a more comprehensive perspective by identifying six general areas of worklife considered as the most important antecedents of burnout: a manageable workload, job control, rewards, community, fairness, and values. According to this model, a mismatch between one's expectations and the structure or process within the occupational environment contributes toward burnout. These six areas have different relationships with the three dimensions of burnout [11,18]. Mainly building on the demand-control theory of job stress described by Karasek and Theorell [19], authors assert that mismatches in workload and job control may aggravate exhaustion through excessive demands, by generating a general condition of anxiety. By contrast, a manageable workload sustains energy, thus contrasting the risk of burnout. A mismatch in workload implies that workers feel overworked and∖or do not have enough time to perform the job. Work overload is a major source of exhaustion that, in turn, is at the root of burnout [14], representing the basic individual stress component of burnout [20]. In addition, a lack of job control means that employees' sense of autonomy and discretion are limited. As a result, their sense of control over what they do is limited or undermined, which also means that they do not have much of a say in what goes on in their work environments. By contrast, job control enables workers to take decisions regarding their work [11]. As described by Leiter and Maslach [11], job control plays an important role in influencing, either directly or indirectly, workload and burnout among employees. In this sense, more control gives workers the opportunity to shape their work environment, such as reducing their workload accordingly. This is in line with the buffer hypothesis of job stress, where high job demands (mainly, a high workload) coupled with low job control lead to job strain. In this sense, it is central to clarify and control the variables involved in the job burnout process. This will enable the development of strategies aimed at protecting health care professionals from the risk of burnout [5].

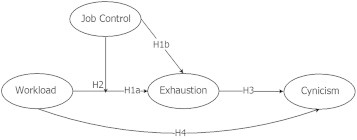

The purpose of this study is to develop and test a conceptual model of the relationship between work environment (workload and job control) and burnout (cynicism and exhaustion) among Italian health care professionals. Specifically, the following working hypotheses were tested (Fig. 1): (1) Hypothesis 1a: workload is positively related to exhaustion; (2) Hypothesis 1b: job control is negatively related to exhaustion; (3) Hypothesis 2: job control moderates the relationship between workload and exhaustion; (4) Hypothesis 3: exhaustion is positively related to cynicism; and (5) Hypothesis 4: exhaustion mediates the relationship between workload and cynicism.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model. H, hypothesis; H1a, workload is positively related to exhaustion; H1b, job control is negatively related to exhaustion; H2, job control moderates the relationship between workload and exhaustion; H3, exhaustion is positively related to cynicism; H4, exhaustion mediates the relationship between workload and cynicism.

2. Materials and methods

The study was performed in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

2.1. Participants and data collection

A cross-sectional survey was conducted. The study participants were recruited in January 2013 from five Italian Hospitals. A total of 352 hospital workers (nurses and other clinical professionals) voluntarily completed a self-administered paper questionnaire that had been distributed to 434 workers, representing a return rate of 81.1%. Researchers provided a briefing on the study objectives as well as statements guaranteeing both confidentiality and anonymity. The hospital workers were given 3 weeks to complete and return their questionnaires in locked boxes.

In total, the sample is composed of 352 health care workers with an average age of 40–46 years. Of these, 74.1% were woman and 61.1% have been working in the actual unit for more than 10 years.

2.2. Ethical permission

Formal approval from the local ethical committee was not required, according to national legislation in Italy.

2.3. Measurements

The exhaustion (5 items) and cynicism (5 items) subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey [13,21] were used to measure burnout. Participants used a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day), to rate the extent to which they experience exhaustion and cynicism at work (e.g., “I feel burned out from my work”). In the present study, the internal reliability for each subscale was 0.87 for exhaustion and 0.77 for cynicism.

Two subscales of the Areas of Worklife Scale [11,22] were used to measure workload (3) and job control (3). The items are worded as statements of perceived congruence or incongruence between oneself and the job. Thus, each subscale includes positively worded items of congruence, for example, “I have enough time to do what's important in my job” (workload), and negatively worded items of incongruence, for example, “Working here forces me to compromise my values” (values). Respondents indicate their degree of agreement with these statements on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree), through 3 (hard to decide), to 5 (strongly agree). Scoring for the negatively worded items is reversed.

The scale has yielded a consistent factor structure across samples with acceptable alpha levels (0.71 for workload and 0.65 for job control). An indication of the subscales' construct validity is that when respondents were given an opportunity to comment on any issue in their worklives, the topics of their complaints corresponded to the areas of worklife that they evaluated negatively [11].

2.4. Data analysis

We tested our study hypotheses using the principles of structural equation modeling techniques with the statistical software package AMOS 19.0 (SPSS: An IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA). Following Anderson and Gerbing's [23] two-step approach, we tested the measurement structure and structural relationships in two separate steps. First, evaluation of the measurement model was carried out using exploratory factor analysis, complemented by confirmatory factor analysis. The second step tests the proposed model along with tests of rival alternative models.

As our hypotheses included both moderation and mediation effects, we had to apply different techniques. In order to investigate the moderation effect (Hypothesis 2), we followed the recommendations of Little et al [24]. In particular, we used orthogonal centered product terms of the latent construct to simulate the interactions in our structural model. First, we multiplied an uncentered indicator of workload with an uncentered indicator of job control. This resulted in nine product terms. Then, we regressed each of the nine products on all indicators. The residual of this regression was saved in the data file. The nine residuals were used for the measurement of the latent product term variable. In the second step, we included the nine orthogonalized product terms as indicators of a single latent interaction construct. For each latent variable [workload, job control, and the latent product (workload * job control)], one factor loading was fixed to 1 to provide a scale for the respective latent variable. In addition, we specified error covariances between the residual variances of the interaction products. To better interpret the interactions, we also performed a graphical plotting of the results and simple slope testing, as proposed by Aiken and West [25]. The significant interaction effects were evident from the plots. Independent lines of regression were generated from the regression equation to represent the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, defining the high and low values of the moderator variable at relatively 1 standard deviation above and below the mean. Following the recommendations of Aiken and West [25], simple effects tests were conducted to determine whether the slopes differed significantly from zero. The mediation effect (Hypothesis 4) was tested in structural equation modeling by comparing the mediation model with the baseline model, and, following the recommendation of Cheung and Lau [26], we also applied bootstrapping procedures to test for the significance of the indirect effect.

We tested our hypothesis by comparing models, using the Δχ2 test with one or two degrees of freedom [27]. Following the recommendation of Bentler [28], in addition to χ2 statistic, the overall fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). As a rule of thumb, applied cutoff values for the IFI and CFI are >0.90 [29] and <0.06 for the RMSEA to indicate an acceptable model fit [30].

3. Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among the variables. The factorial structure of measures (burnout, workload, and job control measures) was examined. All indicators loaded significantly on their corresponding latent constructs (p < 0.001), and the model showed a good fit to the data supporting the hypothesized structure: χ2 (degrees of freedom = 91) = 205.9; IFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.94; and RMSEA = 0.06. We also compared the measurement model with three alternative models (Table 2). First, a three-factor model in which job control and workload items loaded on one common factor (Alternative Model 1) had a significantly worse fit [Δχ2(3) = 91.0; p < 0.001]. Second, a three-factor model with exhaustion and cynicism items loading on one factor (Alternative Model 2) had a worse fit [Δχ2(3) = 72.8; p < 0.001]. Finally, a one-factor model (Alternative Model 3), with all items loading on one common factor, had a worse fit [Δχ2(6) = 231.6; p < 0.001].

Table 1.

Means, SDs, and correlations of variables (N = 352)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload | 3.14 | 1.04 | 1 | |||

| Job control | 3.28 | 0.88 | −0.02 | 1 | ||

| Exhaustion | 2.69 | 1.50 | 0.42∗ | −0.17∗ | 1 | |

| Cynicism | 1.76 | 1.35 | 0.23∗ | −0.19∗ | 0.53∗ | 1 |

SD, standard deviation.

p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Fit indices for measurement models∗

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | IFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-independent-factor measurement model | 205.9 | 91 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.06 | |||

| Alternative model 1 (job control and workload as 1 factor) | 296.9 | 94 | 91.0 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

| Alternative model 2 (exhaustion and cynicism as 1 factor) | 278.7 | 94 | 72.8 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.08 |

| Alternative model 3 (1-factor model) | 437.5 | 97 | 231.6 | 6 | 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.10 |

CFI, comparative fit index; df, degree of freedom; IFI, incremental fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

N = 352. A χ² different test was performed to contrast the measurement model with three nested models.

In the second step of our analysis, we investigated the structural relationships specified in the hypothesized model. We specified paths from the control variables to all dependent study constructs.

3.1. Latent variable model results

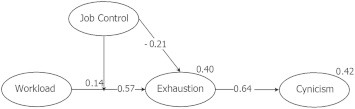

The overall results of the moderated-indirect model suggest that the model fits the data well: χ2 (df = 251) = 390.7; IFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.96; and RMSEA = 0.04. All factor loadings were significant. A look at path coefficients revealed that all paths were significant (p < 0.05). To determine whether our model was parsimonious, the hypothesized model was compared with alternative models that added or dropped paths. As shown in Table 3, first, Alternative Model 1, which allowed a path from workload to cynicism, showed a worse fit: Δχ2(1) = 2.5, which was not significant. Alternative Model 2 restricted the effect of the interaction term to zero and showed a worse fit: Δχ2(1) = 5.7, p < 0.05. Finally, Alternative Model 3, which allowed a path from job control to cynicism, showed a worse fit: Δχ2(1) = 3.0, which was not significant. Overall, the hypothesized model was significantly better than the competing models, confirming all our hypotheses. As proposed in Hypotheses 1a and 1b, workload (β = 0.57, p < 0.001) and job control (β = –.021, p < 0.001) had a hypothesized relationship with exhaustion.

Table 3.

Fit statistics for all models tested∗

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | IFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized model | 390.7 | 251 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.04 | |||

| Alternative model 1 (allowed path: workload → cynicism) | 388.2 | 250 | 2.5 | 1 | ns | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Alternative model 2 (restricted to 0 interaction effect) | 396.2 | 252 | 5.5 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Alternative model 3 (allowed path: job control → cynicism) | 387.7 | 250 | 3 | 1 | ns |

CFI, comparative fit index; df, degree of freedom; IFI, incremental fit index; ns, not significant; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

N = 352. A χ² different test was performed to contrast the measurement model with three nested models.

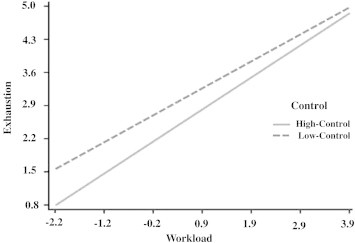

We also observed the expected moderation effect of workload and job control on exhaustion (β = 0.14, p < 0.05; Hypothesis 2). In order to interpret the form of interaction, the equation at the high and low levels of job control was plotted according to the procedure proposed by Aiken and West [25]. The results showed that the form of the interaction was as expected. An increase in the workload was significantly associated with higher job exhaustion; this relationship was attenuated by high job control (Fig. 2). Health care workers were more exhausted in response to higher levels of workload when they had low job control. Thus, Hypothesis 2, about the moderating effect of job control, also was supported.

Fig. 2.

Two-way interaction effect of workload and control on exhaustion.

We also observed the expected relationship between exhaustion and cynicism (β = 0.64, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 3. Finally, because both the relationship between workload and exhaustion and the relationship between exhaustion and cynicism were significant, we carried out bootstrapping procedures, as proposed by Cheung and Lau [26], to test Hypothesis 4. The results from 1,000 bootstrapping samples showed a significant indirect relation between workload and cynicism via transmission of exhaustion (β = 0.45; 95% confidence intervals 0.35–0.39), and thus it confirmed the full mediation hypothesis.

This final model (Fig. 3) accounted for R2 = 40% of variance in exhaustion and R2 = 42% of variance in cynicism.

Fig. 3.

Results of the structural equation modeling analysis of the hypothesized model with standardized path coefficients for mediating and moderating effects. *p < 0.05, two-tailed.

4. Discussion

Burnout among health care workers is associated with high turnover rates and absenteeism due to sickness, relative ineffectiveness in the workplace, as well as low job satisfaction [15,31]. In view of this, it is important to identify organizational stressors that are related to job burnout in order to promote and facilitate strategies aimed at its prevention and reduction.

The key finding of this study was the noteworthy moderation effect of job control on the relationship between workload and exhaustion. This interaction is considered one of the most controversial aspects of Karasek and Theorell's [19] theory. However, previous studies have shown that workload contributes toward the prediction of employee exhaustion [11,32,33], thus indicating incompatibility with Karasek and Theorell's [19] interaction hypothesis. Recently, Taris [34] showed that, of the 90 studies in which this interaction was tested, only nine provided support for the hypothesized interaction. Building on this result, we found a positive association between workload and exhaustion, and this relationship was strongest when job control was lower. In this sense, both workload and job control play important roles in improving working conditions. In turn, improved working conditions are demonstrated by a low workload and exhaustion level, which can also be attributed to an increase in job control. In this manner, job control seems to protect workers from exhaustion when workload increases. Our findings showed that a high workload does not pose major concerns when workers have sufficient job control.

Furthermore, with regard to the burnout dimension, exhaustion was found to be positively associated with cynicism. This result confirmed the well-known sequential progression from exhaustion to cynicism [13], as defined in the theoretical model [13,35]. Specifically, the results are in line with the literature, which indicates that exhaustion occurs first, while cynicism occurs as a reaction to excessive exhaustion [15,36,37].

The well-being of health care workers depends on the quality of their work environment. In the past 30 years, many scholars have examined factors contributing to job burnout. However, further studies focusing on this phenomenon are needed, in order to build and sustain healthy work environments. The results of the present research show the importance of developing organizational management practices that enable job control and provide employees with resources to mitigate the risk of burnout.

Maslach [12] and Maslach and Leiter [11] have argued that organizational interventions aimed at reducing the risk of burnout should be framed according to the dimension considered (exhaustion, cynicism, or sense of efficacy). These authors developed the areas of worklife model [11], proposing that organizational interventions consider policies and practices that are capable of shaping the six key areas of worklife (manageable workload, job control, reward, community, fairness, and values). This suggests that organizations would benefit from interventions aimed at reducing the workload and fostering job control. There is widespread agreement that “preventing burnout is a better strategy than waiting to treat it after it becomes a problem” [38]. In fact, beyond the impact to individual workers' health, burnout also poses risks to others, in the form of workplace accidents, injuries, and fatalities [39]. Furthermore, there is an unexplored issue relating to the crossover effect of burnout. Specifically, it concerns the interpersonal process that occurs when the job stress experienced by one person affects the level of strain experienced by another person in the same social environment [40,41]. Thus, the crossover effect describes the burnout contagion effect among professionals in the same work environments [41].

Although the study findings provide support to the proposed hypotheses, the research design and sample are subject to limitations. First, participants were not randomly selected from the national health care system. This may create a selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results. The study must be replicated by analyzing a larger and more representative sample of health care workers in order to validate the model further. A second limitation is that this study was a cross-sectional study; thus, no hard conclusions can be drawn with regard to causation. Burnout is a process and longitudinal data will be necessary to establish causality among the relationships studied.

To reduce the risk of burnout, intervention programs should be aimed at reducing worker's experience of stressors and, subsequently, should be directed toward both individuals and organizations [42]. Following Leiter and Maslach's [14] approach, in controlling the risk of burnout, health care managers should devise strategies aimed at reducing workers' workload and increasing their sense of control. First, reducing workers' workload when job resources are limited can pose major challenges to health care managers. However, in instances where it is difficult to hire new employees due to economic and regulatory constraints, managers can provisionally reduce the workload by providing employees with a flexible schedule, such as a floating workforce (primarily applicable to nurses). Health care managers may improve workers' sense of control by promoting their autonomy in the workplace. In fact, job autonomy is considered an important coping strategy in decreasing job strain [19,43].

Finally, an interesting avenue for future research is investigation into the contagious nature of burnout by considering the workplace-related crossover effect among health care professionals in a multilevel research design. In this manner, an investigation of crossover as a unit-level factor can expand the current boundaries of burnout models, giving the consideration of a unit burnout level and its effect on individual burnout.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

The authors declare that no funding has been received for this research.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Burton J. World Health Organization; 2010. World Health Organization healthy workplace framework and model: background and supporting literature and practices; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) 2010. WHO healthy workplace framework and model: background and supporting literature and practices.http://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf [cited 2013 Sep 30]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.McVicar A. Workplace stress in nursing: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:633–642. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marine A., Ruotsalainen J.H., Serra C., Verbeek J.H. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2006;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub2. Art. No. CD002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu S., Li H., Zhu W., Lin S., Chai W., Wang X. Effect of work stressors, personal strain, and coping resources on burnout in Chinese medical professionals: a structural equation model. Ind Health. 2012;50:279–287. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieuwenhuijsen K., Bruinvels D., FringsDresen M. Psychosocial work environment and stress related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:277–286. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stansfeld S., Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:443–462. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finney C., Stergiopoulos E., Hensel J., Bonato S., Dewa C.S. Organizational stressors associated with job stress and burnout in correctional officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laschinger H.K.S., Wong C., Greco P. The impact of staff nurse empowerment on person-job fit and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30:358–367. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundin L., Hochwälder J., Bildt C., Lisspers J. The relationship between different work-related sources of social support and burnout among registered and assistant nurses in Sweden: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;44:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leiter M.P., Maslach C. Areas of worklife: a structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In: Perrewé P., Ganster D.C., editors. vol. 3. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 91–134. (Research in occupational stress and well-being). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maslach C. Job burnout: new directions in research and intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maslach C., Jackson S.E., Leiter M.P. 3rd ed. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1996. Maslach burnout inventory manual. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leiter M.P., Maslach C. A mediation model of job burnout. In: Antoniou A.S.G., Cooper C.L., editors. Research companion to organizational health psychology. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham, UK: 2005. pp. 544–564. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslach C., Schaufeli W.B., Leiter M.P. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiter M.P., Harvie P.L., Frizzell C. The correspondence of patient satisfaction and nurse burnout. Soc Sci Med. 1998;37:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslach C., Leiter M.P. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1997. The truth about burnout. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maslach C., Leiter M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:498–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karasek R., Theorell T. Basic Books; New York (NY): 1990. Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslach C. Understanding job burnout. In: Rossi A.M., Perrewe P., Sauter S., editors. Stress and quality of working life: current perspectives in occupational health. Information Age Publishing; Greenwich (CT): 2006. pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaufeli W.B., Leiter M.P., Maslach C., Jackson S.E. The Maslach burnout inventory—general survey. In: Maslach C., Jackson S.E., Leiter M.P., editors. MBI manual. 3rd ed. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto (CA): 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiter M.P., Maslach C. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2000. Preventing burnout and building engagement: a complete program for organizational renewal. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little T.D., Bovaird J.A., Widaman K.F. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: implications for modeling latent variable interactions. Struct Equ Modeling. 2006;13:479–519. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aiken L.S., West S.G. Sage; Newbury Park (CA): 1991. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung G.W., Lau R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ Res Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kline R.B. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; New York (NY): 2005. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bentler P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu L., Bentler P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browne M.W., Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K.A., Long J.S., editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Beverly Hills (CA): 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaufeli W.B., Leiter M.P., Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2008;14:204–220. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leiter M.P., Shaughnessy K. The areas of worklife model of burnout: tests of mediation relationships. Ergonomia Int J. 2006;28:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leiter M.P., Maslach C. Burnout and workplace injuries: a longitudinal analysis. In: Rossi A.M., Quick J.C., Perrewe P.L., editors. Stress and quality of working life: the positive and the negative. Information Age; Greenwich (CT): 2009. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taris T.W. Bricks without clay: on urban myths in occupational health psychology. Work Stress. 2006;20:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W.B., Maslach C., Marek T., editors. Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research. Taylor & Francis; Washington, DC (WC): 1993. pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leiter M.P., Jackson N.J., Shaughnessy K. Contrasting burnout, turnover intention, control, value congruence, and knowledge sharing between boomers and generation X. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16:100–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gascon S., Leiter M.P., Andrés E., Santed M.A., Pereira J.P., Cunha M.J., Albesa A., Montero-Marín J., García-Campayo J., Martínez-Jarreta B. The role of aggressions suffered by healthcare workers as predictors of burnout. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3120–3129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maslach C. Engagement research: some thoughts from a burnout perspective. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2011;20:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nahrgang J.D., Morgeson F.P., Hoffmann D.A. Safety at work: a meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96:71–94. doi: 10.1037/a0021484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolger N., DeLongis A., Kessler R.C., Wethington E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. J Marriage Fam. 1989;51:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westman M., Bakker A.B. Crossover of burnout among health care professionals. In: Halbesleben J., editor. Stress and burnout in health care. Nova Science; Hauppauge, NY: 2008. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Awa W., Plaumann M., Walter U. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hausser J.A., Mojzisch A., Niesel M., Schulz-Hardt S. Ten years on: a review of recent research on the job demand-control (-support) model and psychological well-being. Work Stress. 2010;24:1–35. [Google Scholar]