Abstract

Background:

In Ayurvedic classics, two types of Laghupanchamula -five plant roots (LP) have been mentioned containing four common plants viz. Kantakari, Brihati, Shalaparni, and Prinshniparni and the fifth plant is either Gokshura (LPG) or Eranda (LPE). LP has been documented to have Shothahara (anti-inflammatory), Shulanashka (analgesic), Jvarahara (antipyretic), and Rasayana (rejuvenator) activities.

Aim:

To evaluate the acute toxicity (in mice), analgesic and hypnotic activity (in rats) of 50% ethanolic extract of LPG (LPGE) and LPE (LPEE).

Materials and Methods:

LPEG and LPEE were prepared separately by using 50% ethanol following the standard procedures. A graded dose (250, 500 and 1000 mg/kg) response study for both LPEE and LPGE was carried out for analgesic activity against rat tail flick response which indicated 500 mg/kg as the optimal effective analgesic dose. Hence, 500 mg/kg dose of LPEE and LPGE was used for hot plate test and acetic acid induced writhing model in analgesic activity and for evaluation of hypnotic activity.

Results:

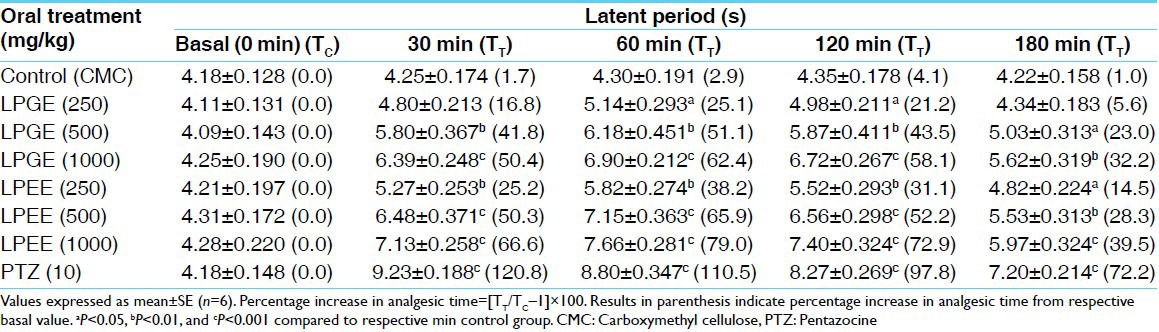

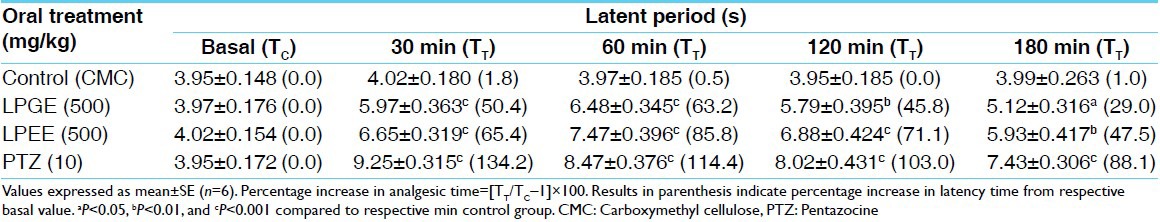

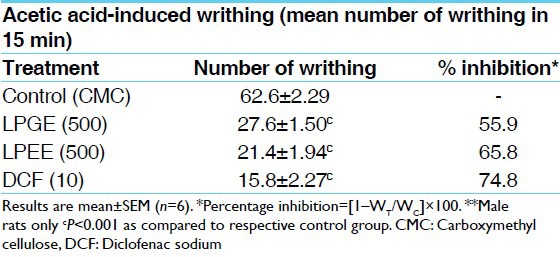

Both the extracts did not produce any acute toxicity in mice at single oral dose of 2.0 g/kg. Both LPGE and LPEE (250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg) showed dose-dependent elevation in pain threshold and peak analgesic effect at 60 min as evidenced by increased latency period in tail-flick method by 25.1-62.4% and 38.2-79.0% respectively. LPGE and LPEE (500 mg/kg) increased reaction time in hot-plate test at peak 60 min analgesic effect by 63.2 and 85.8% and reduction in the number of acetic acid-induced writhes by 55.9 and 65.8% respectively. Both potentiated pentobarbitone-induced hypnosis as indicated by increased duration of sleep in treated rats.

Conclusion:

The analgesic and hypnotic effects of LP formulations authenticate their uses in Ayurvedic system of Medicine for painful conditions.

Keywords: Analgesic, hypnotic potentiation, Laghupanchamula

Introduction

Ayurvedic classics treasures a rich repertory of medicinal plants used for the treatment, management and/or control of different types of Shula and this knowledge is passed from generation to generation.[1] Both the formulations of LP, have been documented in various Ayurvedic classics for Shothahara (anti-inflammatory),[2] Shulanashka (analgesic),[3] Rasayana (antioxidant and rejuvenator),[4] Jvarahara (antipyretic),[5] Kushtha Nashaka (blood purifier activities and useful in skin disorders),[6] and Vranaropaka (wound healing)[7] properties. Two different classical formulations of Laghupanchamula (LP) came into existence with the passage of time containing four common plants viz. Kantakari (Solanum surratense Burm f.), Brihati (Solanum indicum Linn.), Shalaparni (Desmodium gangeticum DC.), and Prinshniparni (Uraria picta Desv.) with either Gokshura (Tribulus terrestris Linn.), advocated in Charaka Samhita,[8] and Chikitsa Granthas like “Chakradatta”,[9] Shargadhara Samhita, Vangasena Samhita, Yogaratnakara, and Bhaisajyasatnavali or roots of Eranda (Ricinus communis Linn.), advocated in Sushruta Samhita,[10] Kashyapa Samhita,[11] and Siddhasara Samhita[12] as the fifth plant.

The plants included under LP have been explored individually for various phytochemicals and pharmacological properties. D. gangeticum DC. (DG) has great therapeutic value in treating typhoid, piles, inflammation, asthma, bronchitis, and dysentery.[13] The aqueous extracts have strong anti-writhing and moderate central nervous system depressant activities. The phytochemical analysis of DG showed the presence of flavonoids, glycosides, pterocarpanoides, lipids, glycolipids, and alkaloids.[14] Isolate obtained from the leaves of U. picta Desv. (UP) exhibited marked bacteriostatic or bacteriosidal and fungistatic or fungicidal activities. Isoflavanones, triterpenes and steroids were isolated from the roots of UP.[15] β-sitosterol, β-sitosterol glucoside, dioscin, methyl protodioscin and protodioscin were isolated from Solanum indicum having many pharmacological activities. Solanum surratence (SS) has high concentration of solasodine, a starting material for the manufacture of cortisone and sex hormone and scientifically reported as antifungal, anti-nociceptive and hypoglycemic.[16] Tribulus terrestris Linn. (TT) have been used in folk medicine as tonic, aphrodisiac, analgesic, astringent, stomachic, anti-hypertensive, diuretic, and urinary anti-infective.[17] TT contained steroidal saponins, and reported to act as a natural testosterone enhancer.[18] Ricinus communis seeds, seed oil, leaves and root have been used for the treatment of inflammation and liver disorder.[19] Pain is centrally modulated via a number of complex processes including opiate, dopaminergic, descending noradrenergic and serotonergic systems. The hot-plate and tail-flick tests are useful in elucidating centrally mediated anti-nociceptive responses, which focuses mainly on changes above the spinal cord level. It is generally accepted that the sedative effects of drugs can be evaluated by measurement of pentobarbital sleeping time in laboratory animals. The prolongation of pentobarbital hypnosis is thus, a good index of Central Nervous System (CNS) depressant activity.[20] Therefore, the present study was undertaken to evaluate analgesic and hypnotic activity of the two classical types of LP, Laghupanchamula with the fifth plant Gokshura (LPG), and Laghupanchamula with the fifth plant Eranda (LPE) using their 50% ethanolic extract, LPG Extract (LPGE) and LPE Extract (LPEE). Tail-flick, hot-plate and acetic acid-induced writhing tests were selected for evaluating analgesic activity and pentobarbitone-induced hypnosis was used for studying their hypnotic potentiating effect in rats. Acute toxicity study was done in mice to see the safety profile of LPEE and LPGE.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Charls-Foster strain albino rats (150-200 g) and Swiss albino mice (20-30 g) of either sex were obtained from the Central Animal House of the Institute. They were kept in the departmental animal house at 24 ± 2°C and relative humidity 44-56%, light and dark cycles of 10 and 14 h respectively for 1 week before and during the experiments. Animals were provided with standard rodent pellet diet. Principles of laboratory animal care (NIH publication no. 82-23, revised 1985) guidelines will be followed. The ethical permission for the investigation of animals used in experiments was taken from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Notification No. Dean/2006-07/810 dated 25.11. 2006).

Collection of plant materials

Roots of Kantakari, Brihati, Shalaparni, Prinshniparni, Eranda, or Gokshura were collected in months of November-December 2006, authenticated in Department of Dravyaguna, Faculty of Ayurveda, IMS, BHU, Varanasi and a sample specimen, of each plant was preserved in the Department (No.-COG/LP-06), for future reference.

Preparation of plant extracts

The collected roots of the above mentioned plants were shade dried and reduced to coarse powder (Sieve no. 8) using a mechanical grinder and stored in air dried containers. 200 g each of dried powder of roots of Kantakari, Brihati, Shalaparni, Prinshniparni plus either Gokshura, i.e. LPG (first combination) or Eranda, i.e., LPE (second combination) were taken. 50% ethanol extracts of 1 kg powder of each LPG and LPE were prepared separately by soxhlation. The percentage yield of LPGE and LPEE was 10.92% and 10.78% respectively.

Drugs and Chemicals

Pentazocin (Fortwin, Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals, New Delhi, India), diclofenac sodium (Jagsonpal Pharmaceuticals, New Delhi, India), acetic acid (Merck, Mumbai, India), pentobarbitone (Loba Chemie, Mumbai, India) were used.

Dose selection and treatment protocol

In the classical texts, for an adult dose of Kvatha (decoction) mentioned is 60 ml/day prepared from ~50 g of the powdered drug.[21] The percentage yield of LPGE and LPEE was ≥10% and considering this, the rat/mouse dose would approximately be 0.5 g/kg body surface area.[22] The test extracts/standard drug was suspended in 0.5% Carboxy-Methyl Cellulose (CMC). The suspension was administered in a volume of 1 ml/100 g body weight, orally, single dose per day with the help of an orogastric tube either just before or 30 min before experiment. A graded dose (250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg) response study for both LPEE and LPGE was carried out for analgesic activity against rat tail-flick response which indicated 500 mg/kg as the optimal effective analgesic dose (>50% response at 120 min peak response). Hence, 500 mg/kg dose of LPEE and LPGE was used for further studies.

Acute toxicity study

Adult Swiss albino mice of either sex, weighing between 20 and 25 g fasted overnight, were used for toxicity study. Suspension of LPGE and LPEE were orally administered at 2 g/kg stat dose (four times of the optimal effective dose of 500 mg/kg) to mice. Subsequent to extracts administration, animals were observed closely for first three hours, for any toxicity manifestation like increased motor activity, salivation, convulsion, coma, and death. Subsequently observations were made at regular intervals for 24 h. The animals were under further investigation up to a period of 2 weeks.[23]

Analgesic activity

Tail-flick test

Control group received 0.5% CMC (1st group) and the treated groups (2nd -7th groups) received 250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg doses of LPGE and LPEE while the 8th group received pentazocine (PTZ, 10 mg/kg). The extracts/drug was administered orally just before experiment. The tail-flick latencies were recorded by analgesiometer (Elite) in sec at pre-drug (basal, 0 min reading) and at 30, 60, 120, 180, and 300 min after administration of CMC/LPGE/LPEE/Pentazocin (PTZ) following the standard procedure. Percent increase in latency period was calculated by following the formula:

[TT/TC–1] × 100,

where, TC and TT were mean analgesic time at basal (0 min) and post-treatment time of 30, 60, 120, 180, and 300 min respectively.[24]

Hot-plate test

Rats were placed on hot-plate kept at 55 ± 0.5°C for a maximum time of 10 s to avoid any thermal injury in the paws. Reaction time was recorded using Eddy's hot-plate apparatus, when the animals licked their fore and hind paws and jumped; at before (basal/0 min) and after 30, 60, 120, 180, and 300 min following administration of CMC (control), LPGE/LPEE (Test drugs, 500 mg/kg) and PTZ (positive control, 10 mg/kg). Reaction time in sec was recorded and percent increase in reaction time was calculated following the formula:

[TT/TC–1] × 100,

where, TC and TT were mean analgesic time at basal (0 min) and post-treatment time of 30, 60, 120, 180, and 300 min respectively.[25]

Acetic acid-induced writhing

Control group received CMC and treated groups received diclofenac (10 mg/kg), or LPGE or LPEE (500 mg/kg). Thirty minutes later, 0.7% acetic acid (10 ml/kg) solution was injected intraperitoneal to all the rats in the different groups. The number of writhes (abdominal constrictions) occurring between 5 and 20 min after acetic acid injection was counted. A significant reduction of writhes in tested animals compared to those in the control group was considered as an anti-nociceptic response.[26]

Hypnotic activity

Control group received CMC and treated groups received LPGE or LPEE (500 mg/kg). Thirty minutes later, sub-hypnotic dose of pentobarbitone (20 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) was administered to each rat of all the groups for observing the potentiation of pentobarbitone-induced hypnosis in rats. Each rat was observed for the time of onset of sleep (time between the administration of pentobarbitone to loss of righting reflex) and duration of sleep (time between the onset of sleep to regaining of righting reflex).[27]

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM) statistical comparison was performed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and for multiple comparisons versus control group was done by Dunnett's t test.

Results

Acute toxicity study

LPGE and LPEE did not produce any mortality during 72 h period at single, 2 g/kg oral dose. Animals showed no stereotypical symptoms associated with toxicity, such as convulsion, ataxia or increased diuresis.

Analgesic activity

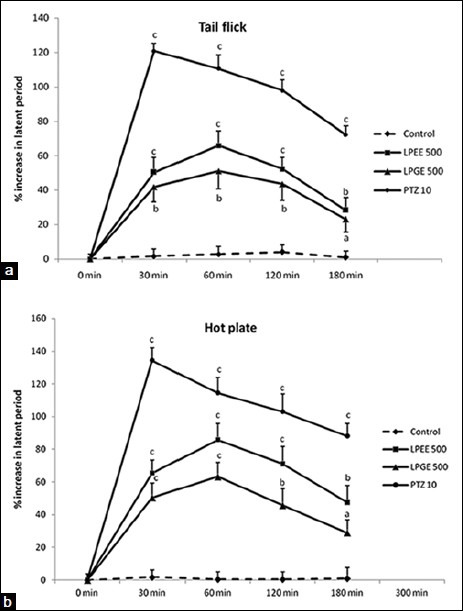

Both, LPGE and LPEE dose-dependently (250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg) increased the latency time in tail-flick test during 180 min of study duration showing peak analgesic effect at 60 min. Therefore for further studies on hot-plate, acetic acid-induced writhing and potentiation of pentobarbitone hypnosis, 500 mg/kg dose of both LPGE and LPEE were selected [Table 1]. LPGE and LPEE (test extracts) at 500 mg/kg dose showed significant analgesic effect from 30 min onwards till the 180 min duration of study period both in tail-flick and hot-plate studies which was comparable with PTZ, positive control [Tables 1 and 2; Figure 1a and b]. Further, both LPGE and LPEE (500 mg/kg) significantly reduced the number of writhing induced by acetic acid in rat [Table 3]. Both LPGE and LPEE showed good analgesic effect that was comparable with the standard drug, PTZ.

Table 1.

Analgesic activity of LPEE and LPGE by tail-flick method in rats

Table 2.

Analgesic activity of LPEE and LPGE by hot-plate method in rats

Figure 1.

(a and b) Analgesic activity of LPEE, LPGE, and pentazocine at 0 min (basal) to 180 min of study duration in tail-flick and hot-plate study methods in terms of % increase in latency period from respective group basal (0 min) value. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, and cP < 0.001 compared to respective min control carboxymethyl cellulose value

Table 3.

Effects of LPEE and LPGE on acetic acid induced writhing in rats

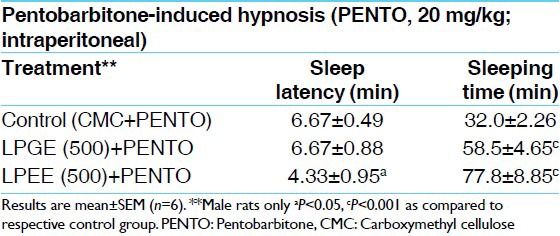

Hypnotic activity

Effects of oral pre-treatment with LPGE and LPEE (500 mg/kg) on the sleep latency and duration induced by sub-hypnotic dose of pentobarbitone (20 mg/kg) are shown in Table 3. LPEE showed early onset of sleep while, both LPGE and LPEE prolonged the sleeping time induced by pentobarbitone [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effects of LPEE and LPGE on pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time in rats

Discussion

The 50% ethanolic extracts of both the formulations of LP - LPG, and LPE, at the dose of 500 mg/kg protected rat against both thermal and chemical-induced noxious stimuli, which were evidenced from their effects on tail-flick hot-plate tests and acetic acid-induced writhing indicating both the central and peripheral components of pain perception [Tables 1ȓ3]. Peripherally acting analgesics act by blocking the generation of impulses at chemoreceptor site of pain, while centrally acting analgesics not only raise the threshold for pain, but also alter the physiological response to pain and suppress the patient's anxiety and apprehension.[28] Analgesic effect mediated through central mechanism indicates the involvement of endogenous opiods peptides and biogenic amines like 5HT.[29] In tail-flick and hot-plate study, pre-treatments with LPGE and LPEE significantly increased the reaction time indicating central mechanism in analgesic action. Acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing is a sensitive visceral pain model which detects anti-nociceptive effects of compounds at dose levels that may appear inactive in tail-flick test.[30] Acetic acid-induced writhing syndromes causes algesia by releasing endogenous substances, prostaglandins (PGs) and bradykinin, which then excite the pain nerve endings to other pain provoking stimuli[31] and the abdominal constriction is related to the sensitization of nociceptive receptors to PGs.[32] Increased level of eicosanoids (Prostaglandin E2, Prostaglandin F2α and Leukotrienes) has been found in the peritoneal fluid after intraperitoneal injection of acetic acid.[33] The analgesic effect of the extract may therefore be due either to its action on visceral receptors sensitive to acetic acid or to the inhibition of the production of algogenic substances or the inhibition at the central level of the transmission of painful messages.

Phytochemical analysis of plants used in LPGE and LPEE reported the presence of flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, essential oils, and saponins.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] Tannins are important compounds known to be potent cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitors and have anti-inflammatory actions.[34] Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects have been observed in flavonoids as well as tannins.[35] Flavonoids have also been reported to possess anti-oxidant and anti-radical properties.[36] As, in the visceral pain model, there is release of arachidonic acid byproducts via cyclooxygenase and lipooxygenase pathways which plays a role in the nociceptive mechanism.[37] So, LPEE and LPGE might be suppressing the formation of eicosanoids or antagonize their action and thus, exert their peripheral analgesic activity in acetic acid-induced writhing test as was observed with diclofenac sodium, a potent cyclooxygenase inhibitor. Analgesics effects of alkaloids, essential oils, and saponins have been observed by various workers.[38,39] Both the extracts potentiated pentobarbitone-induced sleep in rats. It may be assumed that the bioactivity elicited by these extracts may be due partly to its flavonoid and tannin contents, since these have been shown to have analgesic and hypnotic activity. The analgesic and hypnotic effects of the extracts may therefore, be due to the presence of flavonoids, tannins, alkaloid, or saponins. Acute toxicity study in mouse with both the extracts proved them to be safe.

Conclusions

50% ethanolic extract of LP types containing either Gokshura (LPGE) or Eranda (LPEE) at 500 mg/kg oral dose, possessed similar anti-nociceptive and hypnotic activities at both central and peripheral levels which authenticate their use for the treatment of painful conditions as advocated in traditional Ayurvedic system.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rathore B, Ali Mahdi A, Nath Paul B, Narayan Saxena P, Kumar Das S. Indian herbal medicines: Possible potent therapeutic agents for rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;41:12–7. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2007002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agnivesha, Charaka, Dridhabala . Charaka Samhita, Cikitsa Sthana, Abhaya Amalaki Rasayana Pada Adhyaya 1/41-57. In: Tripathi B, editor. Chaukambha Surbharati Prakashan, Varanasi. 3rd ed. 1994. pp. 378–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma PV, editor. Chowkhambha Orientalia, Varanasi. 1st ed. 1994. Chakrapanidatta. Chakradatta, Jvara Chikitsa Adhyaya, 1/169; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadavaji Trikamji., editor. Chowkhambha Orientalia, Varanasi. 7th ed. 2002. Sushruta. Sushruta Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, Sootra Sthana. Dravyasangrhniya Adhyaya 38/66-67; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari PV, editor. Chowkhambha Vishvabharti, Varanasi. 1st ed. 2008. Kashyap. Kashyap Samhita, Khila Sthana; Antervartani Chikitsha Adhyaya, 10/83-87; p. 563. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emmerich RE, editor. 1st ed. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag Gmbh; 1980. Ravigupta. Siddhasara Samhita, 2.29; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agnivesha, Charaka, Dridhabala . Charaka Samhita, Cikitsa Sthana, Shvathu Chikitsa Adhyaya 12/50-52. In: Tripathi B, editor. Chaukambha Surbharati Prakashan, Varanasi. 3rd ed. 1994. p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shastri KA, editor. Chaukambha Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi. 5th ed. 1982. Sushruta, Sushruta Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana, Niruhakrama Cikitsa Adhyaya 38/77-78; pp. 547–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnivesha, Charaka, Dridhabala . Charaka Samhita, Cikitsa Sthana, Abhaya-amalaki Rasayana Pada Adhyaya, 1/1/42. In: Tripathi B, editor. Chaukambha Surbharati Prakashan, Varanasi. 3rd ed. 1994. p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shastri KA, editor. Chaukambha Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi. 5th ed. 1982. Sushruta. Sushruta Samhita, Uttara tantra, Jvara Pratishedha Adhyaya, 39/112; p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibidem, Sushruta Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana, Kushtha Chikitsa Adhyaya, 9/27. :442. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibidem, Sushruta Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana, Vrana Chikitsa Adhyaya, 1/112. :403. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastogi S, Pandey MM, Rawat AK. An ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Desmodium gangeticum (L.) DC. and Desmodium adscendens (Sw.) J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:283–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi H, Parle M. Antiamnesic effects of Desmodium gangeticum in mice. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126:795–804. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman MM, Gibbons S, Gray AI. Isoflavanones from Uraria picta and their antimicrobial activity. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1692–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar N, Prakash D, Kumar P. Wound healing activity of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad and Wendl Fruits. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:470–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasubramani SP, Murugan R, Ravikumar K, Venkatasubramanian P. Development of ITS sequence based molecular marker to distinguish, Tribulus terrestris L.(Zygophyllaceae) from its adulterants. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:503–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Nair V, Gupta YK. Evaluation of the aphrodisiac activity of Tribulus terrestris Linn. in sexually sluggish male albino rats. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:43–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.92512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khairnar PP, Pawar JC, Chaudhari SR. Central nervous system activity of different extracts of Leucas longifolia Benth. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2010;3:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilavarasan R, Mallika M, Venkataraman S. Toxicological assessment of Ricinus communis Linn root extracts. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2011;21:246–50. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2010.538752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annonymous. 2nd ed. Part 1. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Indian System of Medicine and Homoeopathy; 2003. Kvatha churna. Ayurvedic Formulary of India; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh MN. Fundamentals of Experimental Pharmacology. 2nd ed. Calcutta, India: Scientific Book Agency; 1984. Some common evaluation technics; pp. 144–51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gautam MK, Singh A, Rao CV, Goel RK. Toxicological evaluation of Murraya paniculata (L.) leaves extract on rodents. Am J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;7:62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallina CF, Grau JW. Tail-flick test. I: Impact of a suprathreshold exposure to radiant heat on pain reactivity in rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;58:161–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00046-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaz ZR, Mata LV, Calixto JB. Analgesic effect of the herbal medicine catuama in thermal and chemical models of nociception in mice. Phytother Res. 1997;11:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dharmasiri MG, Jayakody JR, Galhena G, Liyanage SS, Ratnasooriya WD. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of mature fresh leaves of Vitex negundo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma SM, Amrisha, Prakash J, Sah VK. Phyto-pharmacognostical investigation and evaluation of anti-inflammatory and sedative hypnotic activity of the leaves of Erythrina indica lam. Anc Sci Life. 2005;25:79–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shreedhara CS, Vaidya VP, Vagdevi HM, Latha KP, Muralikrishna KS, Krupanidhi AM. Screening of Bauhinia purpurea Linn. for analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities. Indian J Pharmacol. 2009;41:75–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.51345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glazer EJ, Steinbusch H, Verhofstad A, Basbaum AI. Serotonin neurons in nucleus raphe dorsalis and paragigantocellularis of the cat contain enkephalin. J Physiol (Paris) 1981;77:241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez MR, Guterres L, Dickel OE, de Castro MR, Henriques AT, de Souza MM, et al. Preliminary studies on the anti-nociceptive activity of Vaccinium ashei berry in experimental animal models. J Med Food. 2010;13:336–42. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shukla S, Mehta A, Mehta P, Vyas SP, Shukla S, Bajpai VK. Studies on anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic properties of Caesalpinia bonducella F. seed oil in experimental animal models. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:61–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Annu W, Latha PG, Shaji J, Anuja GI, Saju SR, Sini S, et al. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and anti-lipid peroxidation studies on leaves of Commiphora caudate (Wight and Arn.) Engl. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed Ts, Magaji M, Yaro A, Musa A, Adamu A. Aqueous methanol extracts of Cochlospermum tinctorium (A. Rich) possess analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities. J Young Pharm. 2011;3:237–42. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.83774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beg S, Swain S, Hasan H, Barkat MA, Hussain MS. Systematic review of herbals as potential anti-inflammatory agents: Recent advances, current clinical status and future perspectives. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5:120–37. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.91102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmadiani A, Hosseiny J, Semnanian S, Javan M, Saeedi F, Kamalinejad M, et al. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72:287–92. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pereira DM, Valentao P, Pereira JA, Andrade PB. Phenolics: From chemistry to biology. Molecules. 2009;14:2202–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413:203–10. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hajhashemi V, Ghannadi A, Jafarabadi H. Black cumin seed essential oil, as a potent analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug. Phytother Res. 2004;18:195–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghannadi A, Hajhashemi V, Jafarabadi H. An investigation of the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Nigella sativa seed polyphenols. J Med Food. 2005;8:488–93. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]