Abstract

Despite concerns around the use of technology-based interventions, they are increasingly being employed by social workers as a direct practice methodology to address the mental health needs of vulnerable clients. Researchers have highlighted the importance of using innovative technologies within social work practice, yet little has been done to summarize the evidence and collectively assess findings. In this systematic review, we describe accounts of technology-based mental health interventions delivered by social workers over the past 10 years. Results highlight the impacts of these tools and summarize advantages and disadvantages to utilizing technologies as a method for delivering or facilitating interventions.

Keywords: technology, mental health, interventions, social work practice, access to care

Introduction

The field of social work has long been identified as a profession that emphasizes personal, client-centered relationships, and social workers have been relatively resistant to the advent of technology-based tools used for therapeutic purposes (Parker-Oliver & Demiris, 2006; Parrott & Madoc-Jones, 2008). Traditional approaches to social work mental health practice have highlighted the risks associated with the integration of technology into social work practice, citing concerns related to confidentiality, client trust, and depersonalization (Parker-Oliver & Demiris, 2006). As a result, there has been slower movement towards the actual implementation of innovative technology-based approaches in social work practice that meet clients' mental health needs (Parker-Oliver & Demiris, 2006). However, there is growing evidence that technological tools can allow for increased access and availability, greater anonymity and avoidance of stigma, extended care interventions outside the bounds of a social worker's office, and enhanced communication between the client and social worker (Barak & Grohol, 2011; Mohr, Burns, Schueller, Clarke, & Klinkman, 2013). Parrott and Madoc-Jones (2008) challenge the limited use of technology for basic monitoring and managerial purposes, and instead have underscored the potential benefits of information and communication technologies that may empower clients and address social and economic isolation. Therapeutic uses of technology in a social work context are varied, including online counseling, self-guided web-based interventions, videoconferencing with a social worker, virtual reality software, electronic social networks, email, and text messaging (Reamer, 2013). Regardless of agency policy or therapist preferences, clients are realizing a wide array of options and associated advantages to receiving services through ubiquitous technologies (Mishna, Bogo, Root, Sawyer, & Khoury-Kassabri, 2012).

More recently, some efforts have been made to both emphasize and harness the power of the Internet to provide ongoing professional education and dissemination of evidence-based findings for social workers and mental health practitioners (Holden, Barker, Rosenberg, & Cohen, 2012; Holden, Tuchman, Barker, Rosenberg, Thazin, Kuppens, & Watson, 2012; Powers, Bowen, & Bowen, 2011). Despite increasing consumer demand for using technologies in therapeutic ways, however, the field of social work continues to question the appropriateness of technology-based interventions as a direct practice methodology (Mattison, 2012). Much conceptual discussion has ensued with regard to benefits and risks associated with including technology as a method for delivering or facilitating social work practice interventions (Brownlee, Graham, Doucette, Hotson, & Halverson, 2010; Wodarski & Frimpong, 2013). For instance, Kimball and Kim (2013) raise important ethical considerations associated with the use of social media in social work practice. Mishna and colleagues (2012), however, contend that the infiltration of technology into social work practice is inevitable, urging social workers to focus their efforts on anticipating ethical and legal dilemmas and utilizing technology-based interventions in appropriate ways that preserve therapeutic relationships. For those who are open to the inclusion of technology in social work practice, there remains considerable debate regarding whether technology should be implemented as a supplement to or substitute for traditional face-to-face approaches (Barak & Grohol, 2011; Wodarski & Frimpong, 2013). Indeed, the struggle to understand the appropriate role of technology in enhancing social work practice is still in its infancy.

Amidst the debate and slow adoption, social workers and mental health therapists are beginning to use novel, technology-based methods (e.g., videoconferencing, web-based interventions) in their practice with patients (e.g., Menon & Rubin, 2011). However, very few authors have summarized these efforts, and less is known about the empirical evidence associated with social workers' involvement in interventions that use technology as a means to provide services to vulnerable clients. In fact, to our knowledge this research represents the first systematic review of published studies examining the use of technology-based interventions within social work practice. In this systematic review, we describe accounts of the implementation of technology among social workers over the past 10 years, assess the reported clinical and experiential impacts of these tools, and summarize advantages and disadvantages to utilizing technologies as a method for delivering or facilitating social work interventions. In doing so, this study both evaluates the current state of technology-based interventions within social work practice and highlights knowledge gaps that call for further empirical research and practice-based evidence.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, studies: a) quantitatively and/or qualitatively assessed an intervention that used some form of technology to deliver and/or enhance the delivery of an intervention; b) explicitly included a social worker in treatment delivery; c) examined the impact of the intervention with at least one mental health outcome; d) were reported in journal articles published between 2004 and 2013; and e) were conducted in the United States.

Search Process

To identify the most appropriate articles relevant to social work and mental health interventions, the following academic databases were searched through EBSCO: Academic Search Complete, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, PsycINFO, CINAHL, CINAHL Plus, PsycARTICLES, MEDLINE, Social Work Abstracts, and PsycCRITIQUES. Three search strings were utilized:

social work, AND

practice OR therapy OR intervention OR treatment, AND

technology OR cybertherapy OR computer OR internet OR mHealth OR m-Health OR eHealth OR e-Health OR mobile phone OR web-based OR electronic OR teleconference OR telehealth OR email OR e-mail.

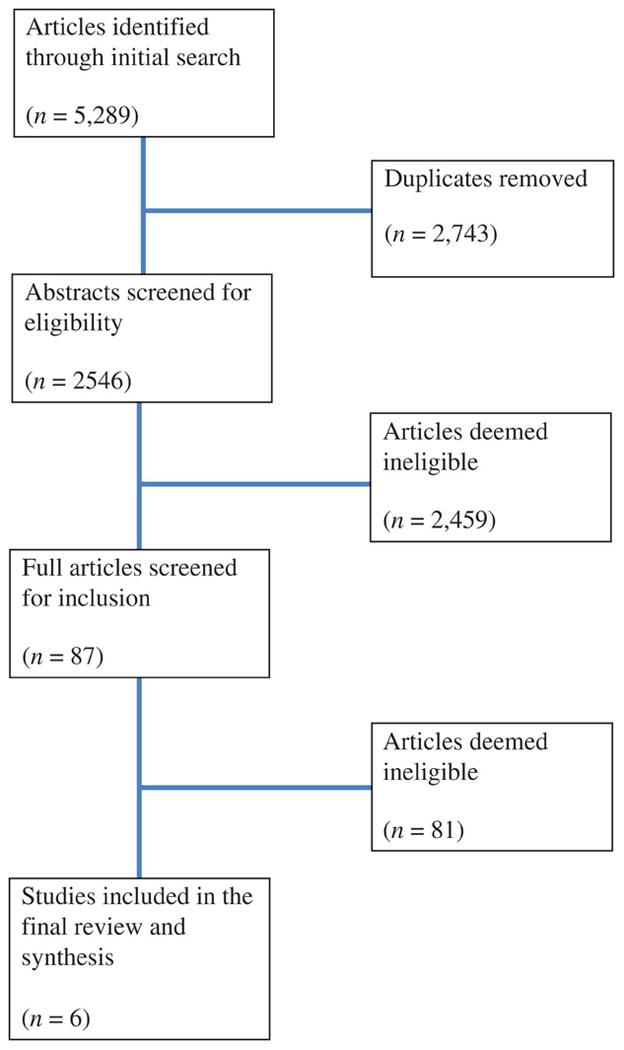

The search revealed 5,289 for the initial screening of abstracts (see Figure 1). Eighty-seven full articles were assessed and resulted in six articles that reported on five studies for the final inclusion.

Figure 1. Screening Flow Chart.

Data Extraction and Coding Procedures

Two reviewers independently screened all of the full articles for inclusion. Results were compared, and the reviewers were found to have 91% agreement. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. For the full coding stage, a coding document was developed to identify and extract sample descriptors, treatment descriptors, research methodology, and mental health and implementation measures. Two reviewers independently coded all final included articles. Results were compared (76% agreement), and all discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The kappa statistic was not calculated, as it has been found to be less meaningful (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008). For example, it is likely that inter-rater reliability would be lower for reviews of articles with poor methodology. For this reason, The Cochrane Collaboration recommends that the double coding process and resolution of discrepancies is necessary, while the calculation of the kappa statistic is not.

Results

Design and Sample

Over half (n = 3) of the studies employed a mix of qualitative and quantitative methodologies (see Table 1). The quantitative study designs ranged from one-group posttest (n =1) to pretest/posttest (n = 2), repeated measures (n = 1), and a randomized controlled trial (n = 1). Intensive interviews (n =1), responses to open-ended questions (n = 1), and content analysis methods (n = 1) were used to gather qualitative data. The majority of sample sizes were generally small, as four of the five studies included 30 or fewer participants. Only one of the studies used a comparison group in their study design, and none of the articles reported on follow-up data.

Table 1. Design, Sample, and Setting Characteristics.

| Citations | Study Methodology | Study Design | N | Control Group | Follow-Up | Participants | Participant Eligibility | Location of Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crawford et al., 2013 | Quantitative | Pretest/Posttest | 17 | no | no |

Mean Age 10.1 Race 76% Caucasian 12% Hispanic 12% Other Gender 70.6% Male |

Anxiety disorder diagnosis | Florida |

| Crunkilton et al., 2008 and Crunkilton, 2009 | Mixed Methods | “Intensive interviews” and One-group posttest | 10 | no | no |

Mean Age 29.2 Race 80% Caucasian 20% African American Gender 60% Male |

Adults enrolled in a Drug Court Program | Medium-sized city in Southeastern U.S. |

| Kernsmith et al., 2008 | Mixed Methods | Content Analysis Pretest/Posttest | 86 | no | no |

Mean Age Unknown Race Unknown Gender 81% Male |

Participants of a self-help group (most had sexually offended against one or more children) | Unknown |

| Parker-Oliver et al., 2006 | Quantitative | Repeated Measures | 2 | no | no |

Mean Age 76 Race Unknown Gender 100% Male |

Hospice caregiver (family member) | Rural area in Missouri |

| Rotondi et al., 2005 | Mixed Methods | Randomized Controlled Trial Open-Ended Questions |

30 | yes | no |

Mean Age 35.7 Race 47% Caucasian 47% African American 6% Other Gender 30% Male |

Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective disorder diagnosis; Age 14 or older; One or more recent hospitalizations; English-speaking; Absence of physical limitations that would interfere with use of a computer | Pittsburgh, PA |

Most of the studies were conducted with adults (n = 4), with an average age range from 29.2 to 76. One study was conducted with only youth, and another study included both adolescents and adults in the eligibility criteria (age 14 and above). It was unknown, however, if Rotondi and colleagues (2005) included adolescents in the final sample. With the exception of one study, most samples included participants who were primarily Caucasian males. The eligibility criteria to participate in the studies were quite varied: specific mental health diagnoses (such as anxiety, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorders), hospice caregivers, adults who were enrolled in a drug court program, or participants involved in a voluntary sexual offender self-help group.

Intervention Characteristics and Mental Health Outcomes

As indicated in Table 2, two of the interventions were delivered online to a group. For the two individually delivered interventions, one was administered via CD-ROM on a computer within a community mental health center, and the other was delivered primarily through the use of a videophone. It was unclear the format through which the fifth intervention was delivered. Two interventions were manualized: Camp Cope-A-Lot (a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention) and the psychoeducational group therapy. Both of these interventions were delivered by a licensed social worker and were considered to be evidence-based interventions. Although the social workers recruited in Parker-Oliver and colleagues' (2006) study were intended to have high involvement in the delivery of services, they noted that the social workers were resistant to participate. Social workers in the remaining two studies (Crunkilton & Robinson, 2008; Crunkilton 2009; Kernsmith & Kernsmith) seemed to provide fewer services. With the exception of one study (Crawford et al., 2013), the extent to which providers were trained in the intervention and specific duration of the treatment was not clear. Four studies reported on services that were delivered in different settings: mental health center, county drug court treatment facility, hospice patient's home, and psychiatric rehabilitation centers. Several mental health outcomes were assessed, but the majority of studies (n = 3) reported on outcomes associated with anxiety symptoms (e.g., stress, obsessive and compulsive thoughts, and general anxiety). Although one study reported no differences in mental health outcomes (Kernsmith & Kernsmith, 2008), most reported empirically or clinically significant benefits. In addition, over half (n = 3) reported on implementation outcomes associated with acceptability and feasibility of the intervention.

Table 2. Intervention Characteristics and Mental Health Outcomes.

| Citations | Name of Intervention |

Manual | Social Worker Role |

Other service providers |

Training in intervention |

Treatment Format |

Treatment Setting |

Duration of Treatment |

Mental Health Outcomes |

Implementation Outcomes |

Primary Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crawford et al., 2013 | Camp Cope-A-Lot (Computer-based and computer assisted CBT) | Yes | Therapists who were not very familiar with CBT | N/A | 2 day training and weekly supervision | Youth and provider Parents and provider | Mental Health Center | 12 weekly 50 minute sessions | Anxiety, global psychopathy, depression, internalizing and externalizing symptoms | Acceptability and feasibility | Significant reductions in anxiety outcomes. |

| Crunkilton et al., 2008 and Crunkilton, 2009 | Drug Court Journey Mapping | No | Not clear (may have facilitated Journey Mapping entry) | Drug Court treatment program director | Unknown | Adults and technology (provider involvement is unclear) | County Drug Court Treatment Facility | An average of 3.1 sessions | Overall well-being | None | Enhanced client's well-being and treatment progress. |

| Kernsmith et al., 2008 | Online Self-Help Group | No | Participated in and observed group | Group facilitators who were recovering offenders | Unknown | Groups of adults and provider | Unknown | Unknown | Cognitive distortions, obsessive and compulsive thoughts | None | Significant decrease in cognitive distortions, compulsions, and obsessions. Higher use of self-help group was significantly associated with outcome benefits. |

| Parker-Oliver et al, 2006 | Telehospice Care | No | Recruit caregivers, train caregivers in technology use, and administer assessment instruments during ongoing work with caregivers | Graduate research assistant and hospice nurse | Yes, but does not state how much training was provided | Adults and provider | Hospice patient's home | Unknown | Anxiety and quality of life | Acceptability and feasibility | Caregivers were generally satisfied with intervention. There were no outcomes differences. |

| Rotondi et al., 2005 | Psycho-education Group Therapy Schizophrenia Guide Website | Yes | Facilitated Group Therapy | N/A | Yes, but does not state how much training was provided | Adults and provider Youth and provider | Psychiatric Rehabilitation Centers | Unknown | Stress | Acceptability Feasibility | Participants in the treatment group with Schizophrenia reported significantly lower levels of stress. |

Use of Technology

Almost all (n = 4) interventions required the use of a computer, three of which also required Internet (see Table 3). The use of technology played a central role in the delivery of all (n = 5) interventions. However, it was largely unclear the extent to which implementers were trained in using the technologies. The use of the technology was generally positive across most (n = 4) of the studies, and several benefits were noted by authors. One of the key benefits across studies was improved accessibility and support that would otherwise not have been received. Although privacy and confidentiality was considered a benefit in one study (Kernsmith & Kernsmith, 2008), it was a potential barrier in another study (Rotondi et al., 2005). Other key barriers included the need to have access to the technology and some difficulty around client use of the technology.

Table 3. Use of Technology.

| Citations | Types of Technology Use | Primary component of practice being delivered or facilitated by technology | Were implementers trained in using technology | Primary benefits using technology | Barriers using technology | General conclusions about technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crawford et al., 2013 | Computer | Therapy sessions | Unknown |

|

|

Positive |

| Crunkilton et al., 2008 and Crunkilton, 2009 | Computer Internet | Narrative therapeutic addition to Drug Court treatment | Unknown |

|

|

Positive |

| Kernsmith et al, 2008 | Computer Internet | Self-Help Group | Unknown |

|

|

Positive |

| Parker-Oliver et al., 2006 | Videophone | Hospice care and assessment | Unknown |

|

|

Mixed |

| Rotondi et al., 2005 | Internet Computers Web-based therapy group Schizophrenia Guide software | Psycho-educational group therapy | Yes, but does not state how much training was provided |

|

|

Positive |

Discussion

The advent of behavioral health interventions delivered or facilitated by information and communication technology is increasingly evident for many conditions, including alcohol and substance abuse, diabetes management, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and insomnia (Lovell & Bee, 2011; Mohr et al., 2013; Staton-Tindall, Wahler, Webster, Godlaski, Freeman, & Leukefeld, 2012). Interestingly, our systematic review yielded only six empirical articles reporting on five technology-based interventions in social work direct practice. The infiltration of technology into the broad mental health arena has progressed at a fairly deliberate pace (Mohr et al., 2013); however, this finding may suggest that the adoption of such tools specifically for social work practice is occurring even more gradually. Furthermore, given that our literature search yielded only one published study since 2009 that met the current criteria, there seems to be little indication that efforts in this area are developing more rapidly in recent years. This may speak to social work values of client trust and personal relationships and, relatedly, caution and skepticism towards innovative changes that could jeopardize these principles (Parker-Oliver & Demiris, 2006). Compared to the medical field, the relevance of new technological innovations to social work practice may be less obvious, perhaps suppressing increased interest in this area. However, the recently concluded 22nd National Institute of Mental Health Conference on Mental Health Services Research focused on “learning mental health care systems” and in particular, the promise and potential of technology to transform mental health care. This may serve to catalyze increased attention to technology-based mental health interventions within the field of social work practice. In any case, the current results call for more empirical research into the ethical, interpersonal, and mental health implications of integrating technology-based methods into social work interventions.

Despite only five studies being identified, the content and target population of the technology-based interventions spanned widely, including manualized computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy to treat childhood anxiety, online self-help groups to manage recovery in sex offending adults, and videophone hospice care support for senior caregivers. Additionally, the treatment settings and primary components delivered varied substantially, further supporting previous findings that technology-based interventions can be applied in-home or in-office to enhance virtually the entire continuum of care, including client assessment, psychoeducation, self-managed care, client-provider communication, and direct treatment (Lord, Trudeau, Black, Lorin, Cooney, Villapiano, & Butler, 2011; Marsch & Gustafson, 2013; Preziosa, Grassi, Gaggioli, & Riva, 2009). As evidenced in this review, technology can extend the reach of care for social workers trained in a particular intervention, and may help social workers provide evidence-based care with higher fidelity. Further research is needed to better understand circumstances in which technology can be used to substitute traditional provider-based care or more appropriately as a supplement to or extension of face-to-face therapy.

The largely positive reports on anxiety and well-being outcomes are encouraging, but should not be perceived as conclusive, particularly for the range of mental health outcomes. Corroborating findings from this review, the efficacy of computer-assisted interventions on anxiety symptoms has been documented in a previous meta-analysis outside the field of social work (Cuijpers et al., 2009). This review should motivate social work researchers to test the effectiveness of technology-based interventions on a broader array of mental and behavioral health outcomes. Furthermore, although more than half of the included studies reported on the acceptance and feasibility of the intervention, the measurement of other implementation outcomes are important and largely unknown with regard to technology-based therapies. Future research in this area would benefit from examining the fidelity of intervention delivery, the appropriateness of technology-enhanced care for certain populations and settings, the cost-effectiveness relative to face-to-face therapy, and long-term sustainability of technology-based interventions with varying levels of therapist involvement.

Due to the highly disparate settings, populations, mental health conditions, interventions, and technologies reported on in this review, it is premature to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of technology-based interventions in social work practice. However, the wide range of benefits reported across studies exemplify the potentially dynamic role that technology can play as the primary mode of delivery or as a feature supporting a larger intervention. Traditional “low-tech” interventions that suffer from limited client reach, poor client-therapist communication, or limited therapist time or training may benefit from incorporating technology-based approaches into treatment delivery. The barriers reported reflect critical concerns that are likely to compromise therapist and/or client utilization, penetration throughout care organizations, and sustainability of technology-based interventions over time. Partnered development of these therapeutic tools that includes all stakeholders (e.g., technologists, researchers, therapists, clients) would likely alleviate many of the unforeseen barriers and improve implementation and client outcomes. Interestingly, however, there were no reports of therapist or client trepidation or negative reactions resulting from a reduced level of therapist contact inherent in the technology-enhanced interventions.

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. The literature search only included published articles retrieved through online databases and, as a result, excluded grey literature. While this approach introduces publication bias, a primary goal of this study was to examine the extent to which the use of technology-based interventions has been reported on through published articles. While this method was deemed appropriate for this study, future reviews may seek to consult unpublished papers, theses and dissertations, conference meeting abstracts, online sources, and study authors through personal contact in order to include a wider array of efforts to integrate technology in social work practice. Further, our review spans approximately 10 years, a period we considered to represent contemporary conceptualizations and applications of technology. While the most recent applications of technology were the focus of the current study, we recognize that this strategy omits years, even decades, of integrating technological approaches into social work practice. In addition, it is possible that some of the articles reviewed did include social workers in the delivery of the intervention, but failed to explicitly report their involvement. Finally, this review only includes studies published in the United States, thereby excluding efforts in Canada, the United Kingdom, and other countries that have explored the use of technology to facilitate social work practice. Because there are many contextual factors that differentially influence the provision of mental health services delivered by social workers around the world, we felt it important to first focus on interventions delivered in the United States. Future studies should consider examining and comparing technology-based interventions across countries.

Conclusion

Despite a historically cautious approach toward the integration of technology into direct social work practice, studies are beginning to report on the implementation of innovative technologies to address the mental health needs for a wide variety of populations, settings, and presenting symptoms. This systematic review of published articles summarizes the current state of technology-based interventions within social work practice and evaluates the reported findings with regard to design, sample, intervention characteristics, mental health outcomes, and the use of technology. Although several barriers to effective technology use were noted across studies, a variety of benefits were reported, and initial evidence suggests that the use of technology-based interventions may be associated with improved mental health outcomes. Further attention from social work researchers and practitioners into the appropriateness, effectiveness, and strategic implementation of technology-based mental health interventions is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research and manuscript preparation was supported by the NIMH T32 Training Grant (T32MH019960).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Alex T. Ramsey, Email: aramsey@brownschool.wustl.edu, Center for Mental Health Services Research, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1196, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130.

Katherine Montgomery, Email: montgomery@brownschool.wustl.edu, Center for Mental Health Services Research, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1093, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130.

References

- Barak A, Grohol JM. Current and future trends in Internet-supported mental health interventions. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2011;29(3):155–196. doi: 10.1080/15228835.2011.616939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee K, Graham JR, Doucette E, Hotson N, Halverson G. Have communication technologies influenced rural social work practice? British Journal of Social Work. 2010;40(2):622–637. [Google Scholar]

- *.Crawford EA, Salloum A, Lewin AB, Andel R, Murphy TK, Storch EA. A pilot study of computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety in community mental health centers. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2013;27(3):221–234. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.27.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Crunkilton DD. Staff and client perspectives on the Journey Mapping online evaluation tool in a drug court program. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2009;32(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Crunkilton DD, Robinson MM. Cracking the “black box”: Journey Mapping's tracking system in a drug court program evaluation. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2008;8(4):511–529. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(2):66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop JM, Fawcett G. Technology-based approaches to social work and social justice. Journal of Policy Practice. 2008;7(2/3):140–154. doi: 10.1080/15588740801937961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden G, Barker K, Rosenberg G, Cohen J. Information for clinical social work practice: A potential solution. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2012;40(2):166–174. doi: 10.1007/s10615-011-0336-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden G, Tuchman E, Barker K, Rosenberg G, Thazin M, Kuppens S, Watson K. A few thoughts on evidence in social work. Social Work in Health Care. 2012;51(6):483–505. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.671649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kernsmith PD, Kernsmith RM. A safe place for predators: Online treatment of recovering sex offenders. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2008;26(2-4):223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball E, Kim J. Virtual boundaries: Ethical considerations for use of social media in social work. Social Work. 2013;58(2):185–188. doi: 10.1093/sw/swt005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord SE, Trudeau KJ, Black RA, Lorin L, Cooney E, Villapiano A, Butler SF. CHAT: Development and validation of a computer-delivered, self-report, substance use assessment for adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(6):781–794. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.538119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell K, Bee P. Optimising treatment resources for OCD: A review of the evidence base for technology-enhanced delivery. Journal of Mental Health. 2011;20(6):525–542. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.608745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Gustafson DH. The role of technology in health care innovation: A commentary. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9(1):101–103. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison M. Social work practice in the digital age: Therapeutic e-mail as a direct practice methodology. Social Work. 2012;57(3):249–258. doi: 10.1093/sw/sws021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon GM, Rubin M. A survey of online practitioners: Implications for education and practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2011;29(2):133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F, Bogo M, Root J, Sawyer J, Khoury-Kassabri M. ‘It just crept in’: The digital age and implications for social work practice. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2012;40(3):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s10615-012-0383-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Burns M, Schueller SM, Clarke G, Klinkman M. Behavioral intervention technologies: Evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):332–338. doi: 10.1O16/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker-Oliver D, Demiris G. Social work informatics: A new specialty. Social Work. 2006;51(2):127–134. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Parker-Oliver DR, Demiris G, Day M, Courtney KL, Porock D. Telehospice support for elder caregivers of hospice patients: Two case studies. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(2):264–267. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott L, Madoc-Jones I. Reclaiming information and communication technologies for empowering social work practice. Journal of Social Work. 2008;8(2):181–197. doi: 10.1177/1468017307084739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JD, Bowen NK, Bowen GL. Supporting evidence-based practice in schools with an online database of best practices. Children & Schools. 2011;33(2):119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Preziosa A, Grassi A, Gaggioli A, Riva G. Therapeutic applications of the mobile phone. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2009;37(3):313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Reamer FG. Social work in a digital age: Ethical and risk management challenges. Social Work. 2013;58(2):163–172. doi: 10.1093/sw/swt003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rotondi AJ, Haas GL, Anderson CM, Newhill CE, Spring MB, Ganguli R, Rosenstock JB. A clinical trial to test the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families: Intervention and 3-month findings. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2005;50(4):325. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Wahler E, Webster JM, Godlaski T, Freeman R, Leukefeld C. Telemedicine-based alcohol services for rural offenders. Psychological Services. 2012;9(3):298. doi: 10.1037/a0026772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarski J, Frimpong J. Application of e-therapy programs to the social work practice. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2013;23(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Youn E. The relationship between technology content in a Masters of Social Work curriculum and technology use in social work practice: A qualitative research study. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2007;25(1/2):45–58. doi: 10.1300/J017v25n01-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]