Abstract

Rationale: Previous respiratory diseases have been associated with increased risk of lung cancer. Respiratory conditions often co-occur and few studies have investigated multiple conditions simultaneously.

Objectives: Investigate lung cancer risk associated with chronic bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and asthma.

Methods: The SYNERGY project pooled information on previous respiratory diseases from 12,739 case subjects and 14,945 control subjects from 7 case–control studies conducted in Europe and Canada. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to investigate the relationship between individual diseases adjusting for co-occurring conditions, and patterns of respiratory disease diagnoses and lung cancer. Analyses were stratified by sex, and adjusted for age, center, ever-employed in a high-risk occupation, education, smoking status, cigarette pack-years, and time since quitting smoking.

Measurements and Main Results: Chronic bronchitis and emphysema were positively associated with lung cancer, after accounting for other respiratory diseases and smoking (e.g., in men: odds ratio [OR], 1.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20–1.48 and OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.21–1.87, respectively). A positive relationship was observed between lung cancer and pneumonia diagnosed 2 years or less before lung cancer (OR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.33–4.70 for men), but not longer. Co-occurrence of chronic bronchitis and emphysema and/or pneumonia had a stronger positive association with lung cancer than chronic bronchitis “only.” Asthma had an inverse association with lung cancer, the association being stronger with an asthma diagnosis 5 years or more before lung cancer compared with shorter.

Conclusions: Findings from this large international case–control consortium indicate that after accounting for co-occurring respiratory diseases, chronic bronchitis and emphysema continue to have a positive association with lung cancer.

Keywords: epidemiologic study, lung neoplasm, pulmonary disease, data pooling, case–control study

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and asthma, when examined individually, have been associated with an increased risk of lung cancer diagnoses.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our results from a large pooled study show that chronic bronchitis and emphysema are positively associated with lung cancer, after accounting for other pulmonary diseases. The positive association between pneumonia and lung cancer was stronger when diagnosed 2 years or fewer before lung cancer diagnoses, compared with longer intervals. Co-occurrence of chronic bronchitis and emphysema and/or pneumonia had a stronger association with lung cancer, compared with chronic bronchitis “only.” Asthma diagnosed 5 years or more prior was inversely related to lung cancer, and no association was observed when asthma co-occurred with chronic bronchitis.

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). Evidence suggests that there is a relationship between previous respiratory disease (PRD), including chronic bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, and pneumonia, and lung cancer diagnoses (2). Tobacco is a shared risk factor of PRD and lung cancer. Yet, the mechanisms by which PRD may independently influence lung cancer risk are poorly understood, but it has been hypothesized that inflammation caused by PRD may act as a catalyst in the development of lung neoplasms (3).

Much of the existing literature focuses on individual PRDs, and does not account for the high level of co-occurrence observed among the various respiratory diseases. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) frequently co-occurs with pneumonia (4) and a medical history of respiratory disease early in life has been related to a later increased risk of asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema (5).

The aim of this pooled analysis was to investigate the relationship between multiple PRDs and lung cancer risk in a large multinational data set with detailed information on smoking habits. To further understand the role of PRD in lung cancer etiology, we investigated the influence of patterns of multiple respiratory diseases and latency of PRD on lung cancer diagnoses.

Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of a conference abstract (6).

Methods

The SYNERGY project is a consortium of international lung cancer case–control studies with information on occupational and lifetime smoking histories (7, 8). More information about the SYNERGY project is available (http://synergy.iarc.fr). Of the participating centers, 13 collected information on PRD. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the studies. Case subjects and control subjects were frequency-matched for sex and age in most studies. Interviews were predominantly conducted through face-to-face interviews, with the exception of the Montreal and Toronto lung cancer studies, which used telephone interviews. Individual countries in the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) multicenter lung cancer study in Central and Eastern Europe and the United Kingdom (INCO) are included as individual studies in these analyses. Ethical approvals were obtained in accordance with legislation in each country, and in addition by the Institutional Review Board at the IARC.

Table 1.

Description of Studies Included in Pooled Analysis

| Study Acronym | Country | Case Subjects |

Control Subjects |

Data Collection | Control Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Response Rate (%) | Number | Response Rate (%) | ||||

| HdA | Germany | 1,004 | 69 | 1,002 | 68 | 1988–1993 | Population |

| AUT | Germany | 3,180 | 77 | 3,249 | 41 | 1990–1995 | Population |

| INCO-Czech Republic | Czech Republic | 304 | 94 | 452 | 80 | 1998–2002 | Hospital |

| INCO-Hungary | Hungary | 391 | 90 | 305 | 100 | 1998–2001 | Hospital |

| INCO-Poland | Poland | 793 | 88 | 835 | 88 | 1998–2002 | Population and hospital |

| INCO-Romania | Romania | 179 | 90 | 225 | 99 | 1998–2001 | Hospital |

| INCO-Russia | Russia | 599 | 96 | 580 | 90 | 1998–2000 | Hospital |

| INCO-Slovakia | Slovakia | 345 | 90 | 285 | 84 | 1998–2002 | Hospital |

| INCO/LLP-UK | UK | 442 | 78 | 917 | 84 | 1998–2005 | Population |

| Montreal | Canada | 1,176 | 85 | 1,505 | 69 | 1996–2002 | Population |

| EAGLE | Italy | 1,921 | 87 | 2,089 | 72 | 2002–2005 | Population |

| ICARE | France | 2,926 | 87 | 3,555 | 81 | 2001–2006 | Population |

| Toronto | Canada | 455 | 62 | 948 | 60 and 84 | 1997–2002 | Population and hospital |

Modified by permission from Reference 36.

In all studies PRD was self-reported (“ever had” or “doctor diagnosed” a disease) and most collected information on five PRDs (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and asthma). INCO/LLP-UK study participants reported “bronchitis” diagnoses. In the Montreal study information on chronic bronchitis was not collected and in the ICARE study emphysema and pneumonia were omitted. The HdA and AUT studies were restricted to PRDs diagnosed at least 2 years before lung cancer diagnoses or control interview.

Statistical Analyses

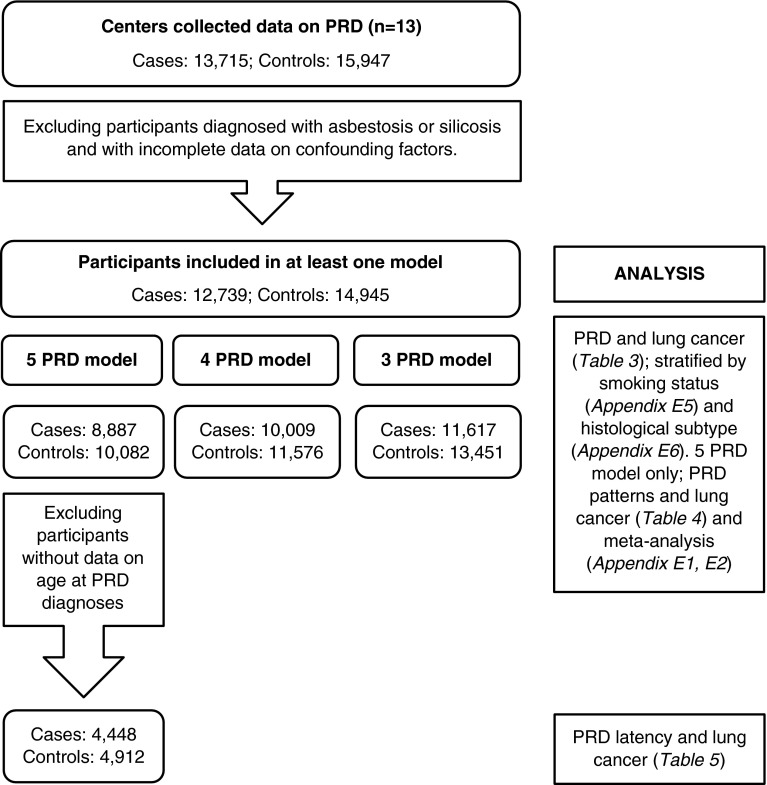

Logistic regression models were fitted to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of lung cancer associated with PRD diagnoses. All PRDs were included in the same model to account for multiple PRD diagnoses. As not all studies collected information on all five PRDs, three models were developed; the first model included all five PRDs (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and asthma); the second, four PRDs (chronic bronchitis omitted); and the third, three PRDs (emphysema and pneumonia omitted) (Figure 1). Subjects with asbestosis (n = 89) and silicosis (n = 110) were omitted, as these diseases are causally associated with known lung carcinogens. Analyses were stratified by sex because of differences in smoking-related exposures observed in men and women. The potential effect of cigarette smoking status was examined by stratifying the analyses; former smokers (stopped ≥5 yr before lung cancer diagnoses or control interview), current smokers (≥1 cigarette per day for ≥1 yr, and participants who quit <5 yr before lung cancer/interview), and never-smokers. Analyses were also stratified by histological subtype to investigate the association between PRD diagnoses and subtypes of lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of exclusion, participants, and analysis. PRD = previous respiratory disease.

A high level of co-occurrence was observed among all PRDs, and thus further analyses were restricted to studies and participants with data on all five PRDs (Figure 1). Patterns of PRD diagnoses with 20 or more case subjects and 20 or more control subjects were investigated and a categorical variable for each PRD was created, indicating whether participants reported the index respiratory disease only, or other co-occurring PRD. Associations were examined using logistic regression models. Because of the small number of women with specific PRD patterns, only associations in men are reported.

The effect of latency of PRD diagnoses on lung cancer risk was investigated in studies with information on age at PRD diagnoses (Figure 1). Three studies did not collect year of PRD diagnoses (HdA, AUT, and INCO/LLP-UK). A latency variable for each PRD was created, indicating whether the diagnoses had been made less than 2, 2–4, 5–9, or 10 or more years before lung cancer/interview. Logistic regression models were fitted to categorical latency variables for each PRD, and adjustments were made for additional PRD diagnosed at any age.

Models were adjusted for center, age (continuous), employment in an occupation with an excess risk of lung cancer (“list A” job [see Appendix E1 in the online supplement; yes/no [9, 10]) and level of education (none, <6, 6–9, 10–13, >13 yr). Additional adjustments were made for cigarette smoking status (current smokers, former smokers, and never-smokers), pack-years (∑duration × average intensity per day/20) and time-since-stopped smoking cigarettes (2–7, 8–15, 16–25, >25 yr), where appropriate. Subjects with missing data on any covariates were omitted from analyses.

Meta-analyses and forest plots were used to explore study-specific ORs and extent of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed using a chi-squared test of the Cochrane Q statistic and I2 statistic. If there was evidence of heterogeneity between studies, outliers were identified using Galbraith plots and removed in sensitivity analysis.

All analyses were conducted with Stata version 11.0 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The Stata command “metan” was used in the meta-analyses.

Results

Study Population

A description of the total study population (12,739 case subjects and 14,945 control subjects) is shown in Table 2. The median age was 63 years for men and 62 years for women. More case subjects than control subjects were current smokers (71 vs. 26% men and 61 vs. 20% women) and the mean cumulative tobacco consumption (cigarette pack-years) was higher in case subjects compared with control subjects (men, 42.7 [SD 26.7] vs. 26.0 [SD 23.2]; women, 35.2 [SD 23.3] vs. 20.0 [SD 18.5]). A greater proportion of women, both case subjects and control subjects, were never-smokers, and, on average consumed less tobacco, compared with men. In case subjects, squamous cell carcinoma was the most frequently characterized histologic subtype among men (41%), compared with adenocarcinoma in women (44%).

Table 2.

Description of Study Population

| Men: %/Mean (n) |

Women: %/Mean (n) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Subjects (n = 9,794) | Control Subjects (n = 11,163) | Case Subjects (n = 2,945) | Control Subjects (n = 3,782) | |

| Age (median), yr | 63 | 62 | 61 | 62 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| None | 1.0 (96) | 0.6 (72) | 0.9 (25) | 0.8 (29) |

| Some primary; <6 yr | 16.9 (1,656) | 11.5 (1,284) | 16.1 (474) | 15.0 (568) |

| Primary/some secondary; 6–9 yr | 52.0 (5,089) | 45.2 (1,330) | 43.8 (4,886) | 38.5 (1,455) |

| Secondary/some college; 10–13 yr | 17.6 (1,720) | 22.3 (656) | 21.9 (2,441) | 25.4 (959) |

| University; >13 yr | 12.6 (1,233) | 22.2 (2,480) | 15.6 (460) | 20.4 (771) |

| “List A” occupation | ||||

| Never | 85.2 (8,347) | 90.2 (10,073) | 94.5 (2,871) | 98.7 (3,734) |

| Ever | 14.8 (1,447) | 9.8 (1,090) | 2.5 (74) | 1.3 (48) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 2.4 (233) | 23.5 (2,627) | 25.4 (749) | 59.0 (2,232) |

| Former (≥5 yr) | 26.6 (2,601) | 43.6 (4,869) | 14.0 (413) | 18.3 (693) |

| Current | 71.1 (6,690) | 32.9 (3,667) | 60.5 (1,783) | 22.7 (857) |

| Pack-years; mean | 42.7 (9,561) | 35.2 (2,196) | 26.0 (8,536) | 20.0 (1,550) |

| Time since cessation of smoking | ||||

| 2–7 yr | 12.6 (1,229) | 7.5 (835) | 8.9 (263) | 4.7 (177) |

| 8–15 yr | 9.6 (944) | 10.0 (1,120) | 5.3 (156) | 4.8 (180) |

| 16–25 yr | 8.2 (806) | 13.8 (1,544) | 3.8 (113) | 5.9 (224) |

| ≥26 yr | 4.8 (469) | 16.0 (2,900) | 2.0 (59) | 5.4 (204) |

| Centers | ||||

| HdA | 7.9 (774) | 7.2 (804) | 5.4 (159) | 4.3 (164) |

| AUT | 26.2 (2,562) | 23.8 (2,654) | 17.5 (514) | 14.4 (545) |

| INCO-Czech Republic | 2.3 (229) | 2.6 (289) | 2.3 (68) | 4.2 (158) |

| INCO-Hungary | 3.2 (312) | 2.2 (247) | 2.9 (86) | 1.7 (64) |

| INCO-Poland | 5.6 (545) | 5.1 (568) | 8.2 (241) | 6.8 (258) |

| INCO-Romania | 1.4 (139) | 1.4 (152) | 1.4 (40) | 2.0 (76) |

| INCO-Russia | 5.3 (516) | 4.5 (501) | 2.7 (79) | 2.0 (77) |

| INCO-Slovakia | 2.9 (385) | 2.1 (234) | 2.0 (58) | 1.3 (49) |

| INCO/LLP-UK | 2.8 (272) | 5.1 (564) | 5.4 (158) | 9.1 (343) |

| Montreal | 6.5 (634) | 7.7 (858) | 14.8 (435) | 15.9 (601) |

| EAGLE | 15.4 (1,503) | 14.3 (1,564) | 13.5 (398) | 13.1 (497) |

| ICARE | 19.3 (1,888) | 22.7 (2,560) | 19.0 (558) | 18.9 (716) |

| Toronto | 1.4 (135) | 1.5 (168) | 1.4 (135) | 6.2 (234) |

| Histologic type* | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 40.8 (3,966) | 19.1 (560) | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 16.4 (1,594) | 17.2 (504) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 25.9 (2,520) | 44.1 (1,291) | ||

The remaining case subjects had other or mixed histology types or information was missing (n = 2,304).

PRD Prevalence

The most frequently reported PRDs were pneumonia (25% of 10,194 case subjects and 18% of 11,642 control subjects) and chronic bronchitis (24% of 11,617 case subjects and 15% of 13,451 control subjects). Emphysema was the least frequently reported PRD (5.0% of 10,106 case subjects and 2.2% of 11,631 control subjects). There was a high level of PRD co-occurrence; of subjects with any PRD, between 50 and 83% of case subjects and 40 and 83% of control subjects reported another, dependent on the index condition (Appendix E2). In particular, a high proportion of participants who reported emphysema (77% of 367 case subjects and 83% of 206 control subjects) or asthma (83% of 620 case subjects and 67% of 535 control subjects) reported another PRD.

PRD and Lung Cancer

In all models persons with chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and pneumonia had an increased risk of lung cancer, compared with persons with no PRD diagnoses. For men, relationships persisted after further adjustment for “list A” occupation, level of education, smoking status, pack-years, and time-since-stopped smoking (Table 3). There was little difference in the strength of association among the PRD models. For women, emphysema and pneumonia remained positively associated with lung cancer after adjustment for confounding factors (not significant for emphysema). Chronic bronchitis was associated with an increased risk of lung cancer in the three-PRD model only (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07–1.47). No relationship between tuberculosis and lung cancer was observed.

Table 3.

Association between Previous Respiratory Disease Diagnoses and Risk of Lung Cancer; Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals Calculated Using Logistic Regression Models

| Five-PRD Models |

Four-PRD Models* |

Three-PRD Models† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Subjects |

Control Subjects |

OR (95% CI) | Case Subjects |

Control Subjects |

OR (95% CI) | Case Subjects |

Control Subjects |

OR (95% CI) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Men | 7,023 | 7,652 | 7,697 | 8,535 | 9,120 | 10,280 | |||||||||

| None | 3,938 | 56.1 | 5,055 | 66.1 | Ref | 5,113 | 66.4 | 6,319 | 74.0 | Ref | 6,459 | 70.8 | 8,182 | 73.6 | Ref |

| Bronchitis | 1,639 | 23.3 | 1,176 | 15.4 | 1.33 (1.20–1.48) | 2,166 | 23.8 | 1,442 | 14.0 | 1.52 (1.39–1.67) | |||||

| Emphysema | 346 | 4.9 | 176 | 2.3 | 1.50 (1.21–1.87) | 398 | 5.2 | 204 | 2.4 | 1.68 (1.37–2.05) | |||||

| Tuberculosis | 349 | 5.0 | 323 | 4.2 | 1.00 (0.83–1.20) | 364 | 4.7 | 341 | 4.0 | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 461 | 5.05 | 427 | 4.15 | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) |

| Pneumonia | 1,750 | 24.9 | 1,444 | 18.9 | 1.24 (1.13–1.37) | 1,945 | 25.3 | 1,580 | 18.5 | 1.36 (1.24–1.48) | |||||

| Asthma | 372 | 5.3 | 402 | 5.3 | 0.89 (0.75–1.07) | 424 | 5.5 | 468 | 5.5 | 0.96 (0.81–1.13) | 540 | 5.9 | 614 | 6.0 | 0.86 (0.74–0.99) |

| Women | 1,864 | 2,430 | 2,312 | 3,041 | 2,497 | 3,171 | |||||||||

| None | 1,056 | 56.7 | 1,514 | 62.3 | Ref | 1,501 | 64.9 | 2,193 | 72.1 | Ref | 1,648 | 66.0 | 2,340 | 73.8 | Ref |

| Bronchitis | 484 | 26.0 | 487 | 20.0 | 1.12 (0.92–1.35) | 673 | 27.0 | 567 | 17.9 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | |||||

| Emphysema | 65 | 3.5 | 43 | 1.8 | 1.35 (0.85–2.12) | 97 | 4.2 | 54 | 1.8 | 1.42 (0.96–2.11) | |||||

| Tuberculosis | 97 | 5.2 | 100 | 4.1 | 1.16 (0.83–1.60) | 108 | 4.7 | 111 | 3.7 | 1.10 (0.80–1.51) | 133 | 5.3 | 130 | 4.1 | 1.21 (0.91–1.60) |

| Pneumonia | 418 | 22.4 | 403 | 16.6 | 1.20 (1.00–1.44) | 605 | 26.2 | 536 | 17.6 | 1.38 (1.18–1.62) | |||||

| Asthma | 139 | 7.5 | 224 | 9.2 | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 199 | 8.6 | 299 | 9.8 | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 233 | 9.3 | 286 | 9.0 | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; PRD = previous respiratory disease.

Participants diagnosed with previous respiratory diseases at any age; participants may be diagnosed with more than one respiratory disease. Analyses include the *Montreal study and the †ICARE study. All previous respiratory diseases included in the same model; further adjustment made for age and center, “list A” occupation, level of education, smoking status, pack-years, and time-since-stopped smoking.

An inverse relationship between asthma and lung cancer was observed in all models. Effect estimates weakened and were no longer significant after controlling for additional confounding factors for men, except in the three-PRD model (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74–0.99). Among women, inverse associations remained in the adjusted five- and four-PRD models.

In the meta-analysis, there was evidence of heterogeneity (P < 0.05) across studies in the chronic bronchitis and pneumonia models, and in the emphysema and asthma models in men (Appendix E3). When outliers were removed there was little change in most of the effect estimates (Appendix E4). For men, no association was found between emphysema and lung cancer (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.68–1.55; I2, 27.9% after outliers removed). For women, no association between pneumonia and lung cancer was found (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62–1.48; I2, 58.5% after outliers removed).

Results stratified by smoking status showed patterns of association in former and current smokers similar to those observed in the overall results (Appendix E5). In never-smokers, numbers were small and no significant risk of lung cancer was found in relation to any of the PRDs; an inverse association between asthma and lung cancer was, however, observed in men in the four-PRD (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.17–0.90) and three-PRD models (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.24–0.98).

Results stratified by lung cancer histological subtype showed that chronic bronchitis and pneumonia were positively associated with all lung cancer subtypes; emphysema was positively related to squamous cell and adenocarcinoma (Appendix E6). Asthma was inversely associated with all lung cancer subtypes among women, and with adenocarcinoma among men.

Patterns of PRD Diagnoses

Because of the high level of co-occurrence among all PRDs and similar findings in all models, the remaining analyses focused on studies with data on all five PRDs.

The relationships between patterns of PRD diagnoses and lung cancer in men are shown in Table 4. Associations reflected previous patterns observed in all models, and relationships persisted after adjustment for confounding factors (Table 4). Chronic bronchitis “only” and pneumonia “only” had a positive relationship with lung cancer (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.21–1.59 and OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.09–1.38, respectively), the strength of association increasing when they co-occurred, and when emphysema was present. A large effect estimate was observed for emphysema “only” (OR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.71–4.21). An inverse relationship was found between asthma “only” and lung cancer (although not significant). There was no association between chronic bronchitis or pneumonia and lung cancer when either co-occurred with asthma or tuberculosis.

Table 4.

Associations between Combinations of Previous Respiratory Disease Diagnoses and Lung Cancer in Men; Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals Calculated Using Logistic Regression Models

| PRD Patterns | Control Subjects |

Case Subjects |

OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Bronchitis (n = 11,808) | 5,577 | 6,231 | ||||

| None | 5,055 | 81.1 | 3,938 | 70.6 | Ref | Ref |

| Bronchitis only | 577 | 9.3 | 751 | 13.5 | 1.81 (1.61, 2.04) | 1.39 (1.21, 1.59) |

| Bronchitis and emphysema | 37 | 0.6 | 77 | 1.4 | 2.69 (1.81, 4.01) | 1.70 (1.09, 2.66) |

| Bronchitis and tuberculosis | 29 | 0.5 | 33 | 0.6 | 1.62 (0.98, 2.70) | 1.04 (0.59, 1.85) |

| Bronchitis and pneumonia | 261 | 4.2 | 431 | 7.7 | 2.26 (1.92, 2.66) | 1.83 (1.52, 2.20) |

| Bronchitis and asthma | 112 | 1.8 | 78 | 1.4 | 1.04 (0.77, 1.40) | 1.03 (0.73, 1.46) |

| Bronchitis and emphysema and pneumonia | 28 | 0.5 | 57 | 1.0 | 2.60 (1.64, 4.11) | 1.69 (1.02, 2.80) |

| Bronchitis and tuberculosis and pneumonia | 32 | 0.5 | 53 | 1.0 | 2.25 (1.44, 3.52) | 1.86 (1.13, 3.04) |

| Bronchitis and pneumonia and asthma | 43 | 0.7 | 73 | 1.3 | 2.47 (1.68, 3.65) | 1.99 (1.27, 3.11) |

| Emphysema (n = 9,515) | 4,284 | 5,231 | ||||

| None | 5,055 | 96.7 | 3,938 | 92.0 | Ref | Ref |

| Emphysema only | 33 | 0.6 | 92 | 2.2 | 3.41 (2.28, 5.10) | 2.68 (1.71, 4.21) |

| Emphysema and bronchitis | 37 | 0.7 | 77 | 1.8 | 2.69 (1.80, 4.00) | 1.67 (1.07, 2.61) |

| Emphysema and bronchitis and pneumonia | 28 | 0.5 | 57 | 1.3 | 2.64 (1.67, 4.18) | 1.69 (1.02, 2.80) |

| Pneumonia (n = 12,187) | 5,688 | 6,499 | ||||

| None | 5,055 | 77.8 | 3,938 | 69.3 | Ref | Ref |

| Pneumonia only | 942 | 14.5 | 972 | 17.1 | 1.26 (1.14, 1.40) | 1.23 (1.09, 1.38) |

| Pneumonia and bronchitis | 261 | 4.0 | 431 | 7.6 | 2.10 (1.79, 2.48) | 1.73 (1.44, 2.07) |

| Pneumonia and tuberculosis | 57 | 0.9 | 58 | 1.0 | 1.21 (0.84, 1.75) | 1.15 (0.75, 1.75) |

| Pneumonia and asthma | 27 | 0.4 | 33 | 0.6 | 1.59 (0.94, 2.68) | 1.46 (0.80, 2.68) |

| Pneumonia and bronchitis and emphysema | 28 | 0.4 | 57 | 1.0 | 2.68 (1.70, 4.24) | 1.71 (1.03, 2.83) |

| Pneumonia and bronchitis and tuberculosis | 32 | 0.5 | 53 | 0.9 | 2.06 (1.32, 3.22) | 1.74 (1.06, 2.85) |

| Pneumonia and bronchitis and asthma | 43 | 0.7 | 73 | 1.3 | 2.27 (1.54, 3.34) | 1.84 (1.18, 2.87) |

| Asthma (n = 9,767) | 4,310 | 5,457 | ||||

| None | 5,055 | 92.7 | 3,938 | 91.4 | Ref | Ref |

| Asthma only | 150 | 2.8 | 82 | 1.9 | 0.76 (0.57, 1.01) | 0.73 (0.53, 1.01) |

| Asthma and bronchitis | 112 | 2.1 | 78 | 1.8 | 1.02 (0.76, 1.38) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.43) |

| Asthma and pneumonia | 27 | 0.5 | 33 | 0.8 | 1.62 (0.96, 2.74) | 1.49 (0.81, 2.74) |

| Asthma and pneumonia and bronchitis | 43 | 0.8 | 73 | 1.7 | 2.28 (1.55, 3.37) | 1.87 (1.19, 2.93) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; PRD = previous respiratory disease.

Participants diagnosed with index previous respiratory disease and other respiratory diseases at any age; that is, participants with data on all five PRDs. Unadjusted models include age and center, adjusted models further adjust for “list A” occupation and level of education, smoking status, pack-years, time-since-stopped smoking.

Latency of PRD

In men, latency of chronic bronchitis and emphysema had little effect on the relationship with lung cancer (Table 5). Relationships remained consistent for chronic bronchitis after adjustment for potential confounding factors. In the adjusted model, there was little difference in the strength of association between emphysema at different latencies and lung cancer; however, only emphysema diagnosed 10 years or more before lung cancer/interview remained statistically significant (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.29–2.92). In women, chronic bronchitis diagnosed 5 years or more before lung cancer/interview and emphysema diagnosed less than 4 years prior were positively associated with lung cancer; relationships attenuated after adjustment for potential confounding factors.

Table 5.

Association between Latency of Previous Respiratory Disease Diagnoses and Lung Cancer Using Logistic Regression Models; Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals Calculated Using Logistic Regression Models

| Latency of PRD Diagnoses* | Men |

Women |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Subjects (n = 4,448) |

Control Subjects (n = 4,912) |

OR (95% CI) |

Case Subjects |

Control Subjects |

OR (95% CI) |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | Model 1 | Model 2 | n | % | n | % | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Bronchitis (n = 7,116) | ||||||||||||

| None | 2,707 | 77.7 | 3,125 | 86.1 | Ref | Ref | 797 | 75.8 | 1,115 | 81.3 | Ref | Ref |

| <2 yr | 110 | 3.2 | 48 | 1.3 | 2.52 (1.78, 3.56) | 1.78 (1.22, 2.61) | 19 | 1.8 | 28 | 2.0 | 0.81 (0.44, 1.49) | 0.58 (0.30, 1.15) |

| 2–4 yr | 60 | 1.7 | 43 | 1.2 | 1.51 (1.01, 2.25) | 1.10 (0.71, 1.72) | 24 | 2.3 | 30 | 2.2 | 0.98 (0.56, 1.72) | 0.77 (0.42, 1.44) |

| 5–9 yr | 85 | 2.4 | 45 | 1.2 | 1.92 (1.32, 2.80) | 1.76 (1.16, 2.68) | 21 | 2.0 | 20 | 1.5 | 1.32 (0.70, 2.50) | 0.98 (0.49, 1.96) |

| ≥10 yr | 524 | 15.0 | 369 | 10.2 | 1.53 (1.31, 1.79) | 1.30 (1.09, 1.55) | 190 | 18.1 | 178 | 13.0 | 1.33 (1.02, 1.73) | 1.18 (0.88, 1.59) |

| Emphysema (n = 7,252) | ||||||||||||

| None | 3,332 | 93.7 | 3,612 | 97.7 | Ref | Ref | 1,063 | 97.1 | 1,381 | 98.6 | Ref | Ref |

| <2 yr | 35 | 1.0 | 12 | 0.3 | 3.04 (1.56, 5.94) | 1.94 (0.96, 3.93) | 12 | 1.1 | 5 | 0.4 | 3.17 (1.09, 9.17) | 1.99 (0.62, 6.42) |

| 2–4 yr | 37 | 1.0 | 15 | 0.4 | 2.56 (1.39, 4.71) | 1.98 (0.97, 4.03) | 9 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.3 | 2.31 (0.70, 7.67) | 1.17 (0.31, 4.34) |

| 5–9 yr | 40 | 1.1 | 17 | 0.5 | 2.34 (1.31, 4.18) | 1.60 (0.84, 3.04) | 3 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.94 (0.21, 4.31) | 0.36 (0.06, 2.22) |

| ≥10 yr | 111 | 3.1 | 41 | 1.1 | 2.42 (1.67, 3.51) | 1.94 (1.29, 2.92) | 8 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.5 | 1.14 (0.41, 3.22) | 0.81 (0.26, 2.56) |

| Tuberculosis (n = 7,276) | ||||||||||||

| None | 3,380 | 94.5 | 3,546 | 95.8 | Ref | Ref | 1,038 | 94.5 | 1,352 | 96.6 | Ref | Ref |

| <2 yr | 12 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.1 | 2.28 (0.79, 6.54) | 1.37 (0.47, 3.98) | 5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2–4 yr | 12 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.1 | 3.76 (1.05, 13.56) | 3.26 (0.80, 13.25) | 3 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 5.31 (0.54, 51.77) | 5.06 (0.44, 58.33) |

| 5–9 yr | 14 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.2 | 1.79 (0.71, 4.54) | 1.03 (0.40, 2.65) | 6 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| ≥10 yr | 158 | 4.4 | 139 | 3.8 | 1.07 (0.84, 1.36) | 1.06 (0.81, 1.39) | 47 | 4.3 | 47 | 3.4 | 1.16 (0.76, 1.78) | 1.12 (0.70, 1.79) |

| Pneumonia (n = 7,188) | ||||||||||||

| None | 2,639 | 74.6 | 2,939 | 80.5 | Ref | Ref | 860 | 79.3 | 1,152 | 83.5 | Ref | Ref |

| <2 yr | 167 | 4.7 | 53 | 1.5 | 3.10 (2.25, 4.27) | 3.31 (2.33, 4.70) | 41 | 3.8 | 27 | 2.0 | 1.63 (0.98, 2.71) | 1.21 (0.70, 2.08) |

| 2–4 yr | 68 | 1.9 | 50 | 1.4 | 1.30 (0.89, 1.90) | 0.94 (0.63, 1.43) | 20 | 1.9 | 26 | 1.9 | 0.89 (0.49, 1.63) | 0.78 (0.40, 1.52) |

| 5–9 yr | 76 | 2.2 | 46 | 1.3 | 1.61 (1.10, 2.34) | 1.82 (1.19, 2.78) | 21 | 1.9 | 20 | 1.5 | 1.29 (0.68, 2.42) | 1.07 (0.54, 2.14) |

| ≥10 yr | 588 | 16.6 | 562 | 15.4 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.21) | 142 | 13.1 | 154 | 11.2 | 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | 0.90 (0.68, 1.20) |

| Asthma (n = 7,253) | ||||||||||||

| None | 3,416 | 95.9 | 3,519 | 95.3 | Ref | Ref | 1,020 | 93.2 | 1,276 | 91.7 | Ref | Ref |

| <2 yr | 28 | 0.8 | 21 | 0.6 | 1.08 (0.60, 1.93) | 1.21 (0.62, 2.40) | 13 | 1.2 | 15 | 1.1 | 0.99 (0.45, 2.15) | 1.32 (0.58, 3.00) |

| 2–4 yr | 20 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.4 | 1.15 (0.56, 2.34) | 0.82 (0.37, 1.79) | 11 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.4 | 0.65 (0.30, 1.39) | 0.57 (0.24, 1.37) |

| 5–9 yr | 26 | 0.7 | 31 | 0.8 | 0.60 (0.35, 1.03) | 0.44 (0.24, 0.79) | 12 | 1.1 | 23 | 1.7 | 0.66 (0.32, 1.35) | 0.64 (0.28, 1.43) |

| ≥10 yr | 71 | 2.0 | 107 | 2.9 | 0.51 (0.37, 0.70) | 0.67 (0.47, 0.98) | 38 | 3.5 | 58 | 4.2 | 0.79 (0.51, 1.22) | 0.83 (0.51, 1.35) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; PRD = previous respiratory disease.

Number of years index respiratory disease diagnosed before lung cancer diagnoses or control interview. Participants restricted to those with age of diagnoses for index respiratory disease and complete data on other four respiratory diseases; that is, participants with data on five PRDs. Unadjusted models include age and center, adjusted models further adjust for “list A” occupation and level of education, smoking status, pack-years, time-since-stopped smoking.

Tuberculosis diagnosed 2–4 years prior had an OR of 3.76 (95% CI, 1.05–13.56) for men and an OR of 5.31 (95% CI, 0.54–51.77) for women, the effect estimates remaining in the adjusted model (OR, 3.26; 95% CI, 0.80–13.25 and OR, 5.06; 95% CI, 0.44–58.33 for men and women, respectively).

For pneumonia, effect estimates were similar in both unadjusted and adjusted models and stronger relationships were observed in the shorter latencies, compared with longer; for example, in men: OR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.33–4.70 and OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.19–2.78 for less than 2 and 5–9 years, respectively.

Asthma diagnosed at least 5 years prior was inversely related to lung cancer among men; weaker or no associations were observed at other latencies. In women, asthma diagnosed at least 2 years prior had an inverse relationship with lung cancer in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, although the 95% CI included the null effect.

Discussion

In this investigation we pooled data from case–control studies in Europe and Canada to examine the association between multiple PRD and lung cancer. A high level of co-occurrence among various PRDs was observed. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema were positively associated with lung cancer, irrespective of the latency between PRD diagnoses and lung cancer/interview. Pneumonia had a positive association with lung cancer, the relationship being stronger for pneumonia diagnosed less than 2 years before lung cancer diagnoses compared with those diagnosed later. Asthma had an inverse association with lung cancer, the association being stronger for asthma diagnosed at least 5 years before lung cancer compared with less than 5 years. No association was observed between tuberculosis and lung cancer after accounting for confounding factors. Co-occurrence of chronic bronchitis and either/both emphysema and pneumonia had a stronger positive association with lung cancer than chronic bronchitis “only,” with emphysema diagnoses being particularly important. Chronic bronchitis was not associated with lung cancer when it co-occurred with asthma.

Methodological Considerations

The study strengths include the large sample size and detailed information on lifetime smoking history. Data on multiple PRDs were collected, and thus the relationship between patterns of PRD and lung cancer could be investigated. Limitations include some centers using hospital-based control selection, the low response rate among control subjects in the AUT study (40%), and the small number of never-smokers. There was limited detail on the respiratory diseases, for example, investigation of atopic and allergic subtypes of asthma was not possible. The comparability of chronic bronchitis between studies may be limited due to differences in the definition of the condition. Most studies reported diagnoses of “chronic bronchitis,” whereas INCO/LLP-UK studies used a broader definition of the disease, asking participants whether they had had “bronchitis,” which includes acute and chronic subtypes. However, sensitivity analysis excluding the INCO/LLP-UK studies found little difference in the results (data not shown).

Temporality is an important consideration when investigating PRD and lung cancer as some of the conditions resemble the early symptoms of lung cancer. Latency analysis was possible in studies that collected age at PRD diagnoses. Excluding participants without age at PRD diagnoses reduced the sample size by almost 50% and missing data may have influenced the relationship between PRD and lung cancer. However, overall patterns of association were comparable between the full and restricted study sample, indicating that missing data may not have influenced the associations (data not shown).

PRD diagnoses were self-reported and participants may have misreported their disease status (11, 12). The lack of medical records or spirometry data limit the validity of the disease definition, and this may have varied by PRD. For example, diagnosis of emphysema requires sensitive pulmonary function tests compared with a sputum test for tuberculosis. Studies that have compared self-reported data and medical records of chronic respiratory diseases have found good agreement for the absence or presence of asthma (13, 14), and moderate to poor agreement for COPD, emphysema, pneumonia, and tuberculosis (15, 16). However, self-reported COPD has been shown to have a high level of agreement with spirometry results (17, 18). Recall bias is a potential problem in all case–control studies and it is possible that misclassification may have introduced some bias here. Nevertheless, case subjects did not report all PRDs at a consistently higher level than control subjects, as shown by the positive association between chronic bronchitis and emphysema with lung cancer, null association for tuberculosis, and an inverse relationship for asthma, indicating that recall bias may not have had a strong influence on the results (19). Differences in the severity or treatment of the PRD could also mean that participants who report different diseases may differently recall exposure to other risk factors, such as smoking history. Never-smokers were investigated in this study, but because of small numbers, the results were difficult to interpret.

Interpretation of Findings and Comparison with the Literature

Co-occurrence of PRD.

Co-occurrence of different pulmonary conditions was common in the SYNERGY consortium, as shown elsewhere. In particular, asthma and emphysema were rarely reported in isolation, compared with other PRDs. In an Italian general population study 13% of adults reported a physician’s diagnoses of asthma and COPD, the proportion increasing to 20% among participants aged 65 years and older (20). Clinical record studies have reported high levels of co-occurrence of respiratory diseases (21). An American study found that 47% of patients more than 65 years of age and hospitalized for pneumonia had a comorbid chronic pulmonary disease (22). Our estimates of co-occurrence are at the upper end of previously reported figures; of participants who reported one PRD, 31.3% of case subjects and 26.3% of control subjects reported two or more PRDs. Respiratory diseases often share symptoms, for example, COPD and asthma. The overlap of asthma and COPD diagnoses can reach 20% of all patients with chronic respiratory disease (23). A previous diagnosis of a respiratory disease is also associated with an increased risk of future diagnoses of another respiratory disease. Prior tuberculosis infection has been associated with irreversible airway obstruction and an increased risk of COPD, and childhood pneumonia is linked to an increased risk of major respiratory diseases in adulthood (24). Given the high proportion of patients with multiple pulmonary diseases, it is important to account for multiple diagnoses when investigating the independent contribution of each respiratory disease to cancer risk.

Chronic bronchitis and emphysema and lung cancer.

Findings in this study of a positive association between chronic bronchitis and emphysema and lung cancer are consistent with previous pooled analysis, which also included the AUT, Toronto, and INCO/LLP-UK studies. Brenner and colleagues (2) observed an average overall relative risk of 1.47 (95% CI, 1.29–1.68) from 13 studies and 2.33 (95% CI, 1.86–2.94) from 16 studies for chronic bronchitis and emphysema, respectively. Comparable independent associations were observed in this study, irrespective of latency. Often chronic bronchitis and emphysema are grouped together, along with other pulmonary syndromes, into COPD, despite heterogeneity in their clinical presentation, physiology, response to therapy, decline in lung function, and survival (25). It is important to investigate chronic bronchitis and emphysema separately as grouping them may mask differences in their association with lung cancer. As shown here, individual conditions and different patterns of PRD had unique and independent associations with lung cancer.

Emphysema was found to have a stronger association with lung cancer, compared with chronic bronchitis as well as other PRDs. Studies that have investigated chronic bronchitis and emphysema separately have reported similar findings (2, 26). A 20-year follow-up study of 448,600 lifelong nonsmokers reported that lung cancer mortality was significantly associated with both emphysema (hazard ratio [HR], 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.6), and emphysema combined with chronic bronchitis (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.2–4.9), but not with chronic bronchitis alone (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.7–1.3) (27).

A potential explanation for the increase in lung cancer risk is the inflammatory response to chronic bronchitis and emphysema, which is conducive to tumor initiation (3). Increases in genetic mutations, angiogenesis (28), and antiapoptotic signaling (29) are potential processes through which inflammation may increase the risk of cancer development.

Pneumonia and lung cancer.

Pneumonia had a positive relationship with lung cancer, but there was some indication that the time between pneumonia and lung cancer diagnoses may influence the relationship. A stronger effect was shown between pneumonia with shorter latencies and lung cancer, compared with those diagnosed later. In a prospective U.K. study of primary care data, the association between pneumonia and lung cancer was influenced by timing of diagnoses; greater effect estimates were observed with pneumonia diagnosed within 6 months of lung cancer diagnosis (OR, 13.3) compared with 1–5 years (OR, 1.34) (30). People with symptoms or diagnoses of a pulmonary disease are more likely to undergo further clinical investigation than those without, providing greater opportunity for a subsequent diagnoses of lung cancer. The strong association with short latency may also reflect reverse causality, as bronchial suppression or immunosuppression caused by a tumor may make patients more susceptible to infection. The association between pneumonia and lung cancer may therefore be partially explained by the misdiagnoses of early lung cancer symptoms or ascertainment bias due to increased monitoring of patients.

Asthma and lung cancer.

Here an inverse association between asthma and lung cancer was observed, with the relationship stronger with longer compared with shorter latencies. A previous meta-analysis of existing studies found a positive relationship between asthma and lung cancer, with a stronger relationship in recent studies and shorter latencies (31). In subgroup analysis, they stratified by other respiratory diseases and found an inverse relationship between asthma and lung cancer in studies that adjusted for co-occurring chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD (shown in Table E1 in the online supplement). Rosenberger and colleagues concluded that there was no clear evidence of an independent association between asthma and lung cancer (31). Avoidance of known risk factors, such as tobacco smoking, and working in “clean” industries may partially explain the inverse association and the strong association observed among participants diagnosed with asthma at least 10 years before lung cancer/interview. A greater proportion of participants who reported asthma were classified as never-smokers (21%), compared with those who reported emphysema (9%), chronic bronchitis (14%), and pneumonia (15%). It has been hypothesized that asthma may reduce the risk of lung cancer, thus counteracting the association with other respiratory diseases, through a more efficient elimination of abnormal cells (32). Long-term steroid treatment (inhalers or tablets) can have an important effect of the inflammation pathway and could also biologically explain the inverse relationship. Information on treatment or grade of asthma was not available in these studies and could not be investigated here.

Tuberculosis and lung cancer.

The published literature on tuberculosis and lung cancer is mixed. A meta-analysis found that tuberculosis was associated with adenocarcinoma lung cancer, but not squamous or small cell carcinoma (33). Findings from this study, of overall no association between tuberculosis and lung cancer, are consistent with a previous investigation of tuberculosis which accounted for co-occurring pulmonary diseases, such as chronic bronchitis and asthma (34). However, the number of case subjects with tuberculosis in this consortium was small and thus results should be interpreted with caution.

Multiple PRDs and lung cancer.

Our study is one of a few that report on the relationship between multiple types of pulmonary diseases and lung cancer. There was a stronger association with lung cancer with increasing number of pulmonary diseases (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and pneumonia). Yet, no association was observed between chronic bronchitis and lung cancer when asthma was also reported. Other studies have observed similar results. A Hong Kong longitudinal study that grouped COPD and asthma observed no association with lung cancer mortality in female never-smokers (35). A Chinese occupational cohort study examining chronic bronchitis, asthma, and tuberculosis found that only prior chronic bronchitis was associated with an increased lung cancer risk, with an adjusted HR of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.24–1.81), after including all respiratory diseases in the same model (34). A general practice study in the United Kingdom found no independent association between asthma and lung cancer after excluding all patients with a diagnoses of COPD (30).

Conclusions

Findings from this large international case–control consortium indicate that individual respiratory diseases may be differentially associated with lung cancer, after accounting for co-occurring PRD. The pooling of data provided the power to investigate multiple PRDs and different histological subtypes of lung cancer, which was not possible in the individual lung cancer case–control studies. Respiratory diseases, such as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma, are conditions frequently found in the general population, and thus identifying those at greater risk would be of clinical importance. PRDs frequently co-occur and in this study, the relationship between different patterns of PRD diagnoses and lung cancer varied, with emphysema being particularly important whereas co-occurring asthma and chronic bronchitis were not associated with lung cancer. The different associations found with each PRD may support the hypothesis of a different biological mechanism underlying the etiological pathway from a specific respiratory disease to lung cancer. These findings could be used to identify potentially vulnerable groups, and inform the type and periodicity of clinical surveillance recommended for each PRD. Further investigation of our observed associations is needed to characterize high-risk groups, which could then be used to develop opportunities for early disease detection.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Mrs. Veronique Benhaim-Luzon (IARC) for data management.

Footnotes

Supported by the Institut National du Cancer in France (Projets Libre Epidemiologie 2009). The SYNERGY project was funded by the German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV). The Montreal study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and Guzzo-SRC Chair in Environment and Cancer. The Toronto study was funded by the National Cancer Institute of Canada with funds provided by the Canadian Cancer Society, and the occupational analysis was conducted by the Occupational Cancer Research Centre, which was supported by the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, the Canadian Cancer Society, and Cancer Care Ontario. The ICARE study was supported by the French Agency of Health Security (ANSES); the Fondation de France; the French National Research Agency (ANR); the National Institute of Cancer (INCA); the Foundation for Medical Research (FRM); the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS); the Health Ministry (DGS); the Organization for the Research on Cancer (ARC); and the French Ministry of Work, Solidarity, and Public Function (DGT). The AUT study in Germany was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Technology grant no. 01 HK 173/0. The HdA study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Science (grant 01 HK 546/8) and the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (grant IIIb7-27/13). The INCO study was supported by a grant from the European Commission’s INCO-COPERNICUS program (contract IC15-CT96-0313). In Warsaw, the study was supported by a grant from the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research (grant SPUB-M-COPERNICUS/P-05/DZ-30/99/2000). The Liverpool Lung Project (LLP) was supported by the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. The EAGLE study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (Bethesda, MD); the Environmental Epidemiology Program of the Lombardy Region, Italy; and the Istituto Nazionale per l’Assicurazione contro gli Infortuni sul Lavoro (Rome, Italy).

Author Contributions: R.D. conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft and most of the paper. A.C.O., K.S., P.B., and I.S. launched this project and have been involved in all steps. J. Schüz, D.R.B., and S.D.M. participated in the writing, including revising several drafts. T. Brüning, H.K., R.V., S.P., and B.K. have been involved in the coordination of the SYNERGY project since it started in 2007; T. Behrens joined the coordinating team in 2011. All other authors have contributed substantially to the original studies, that is, designed and directed their implementation, including quality assurance and control. All authors have received drafts of the manuscript and have suggested additional analyses and contributed to the interpretation and discussion.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0338OC on July 23, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner DR, Boffetta P, Duell EJ, Bickeböller H, Rosenberger A, McCormack V, Muscat JE, Yang P, Wichmann HE, Brueske-Hohlfeld I, et al. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:573–585. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ, Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:549–555. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-148ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galobardes B, McCarron P, Jeffreys M, Davey Smith G. Association between early life history of respiratory disease and morbidity and mortality in adulthood. Thorax. 2008;63:423–429. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.086744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denholm R Olsson A Deepak D Stucker I Jockel KH Straif K, Schüz J SYNERGY-INCA study group. Previous pulmonary disease and lung cancer risk in a multi-national consortium of case–control studies [abstract]. Presented at the European Congress of Epidemiology (EUROEPI). August 11–14, 2013, Aarhus, Denmark. Abstract 0-012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pesch B, Kendzia B, Gustavsson P, Jöckel KH, Johnen G, Pohlabeln H, Olsson A, Ahrens W, Gross IM, Brüske I, et al. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer—relative risk estimates for the major histological types from a pooled analysis of case–control studies. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1210–1219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters S, Vermeulen R, Cassidy A, Mannetje A, van Tongeren M, Boffetta P, Straif K, Kromhout H INCO Group. Comparison of exposure assessment methods for occupational carcinogens in a multi-centre lung cancer case–control study. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:148–153. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.055608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahrens W, Merletti F. A standard tool for the analysis of occupational lung cancer in epidemiologic studies. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:236–240. doi: 10.1179/oeh.1998.4.4.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirabelli D, Chiusolo M, Calisti R, Massacesi S, Richiardi L, Nesti M, Merletti F. [Database of occupations and industrial activities that involve the risk of pulmonary tumors] Epidemiol Prev. 2001;25:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Torres JP, Bastarrika G, Wisnivesky JP, Alcaide AB, Campo A, Seijo LM, Pueyo JC, Villanueva A, Lozano MD, Montes U, et al. Assessing the relationship between lung cancer risk and emphysema detected on low-dose CT of the chest. Chest. 2007;132:1932–1938. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, Black PN, Metcalf P, Gamble GD. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:380–386. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abramson MJ, Schattner RL, Sulaiman ND, Del Colle EA, Aroni R, Thien F. Accuracy of asthma and COPD diagnosis in Australian general practice: a mixed methods study. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:167–173. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weakley J, Webber MP, Ye F, Zeig-Owens R, Cohen HW, Hall CB, Kelly K, Prezant DJ. Agreement between obstructive airways disease diagnoses from self-report questionnaires and medical records. Prev Med. 2013;57:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iversen L, Hannaford PC, Godden DJ, Price D. Do people self-reporting information about chronic respiratory disease have corroborative evidence in their general practice medical records? A study of intermethod reliability. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:162–168. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muggah E, Graves E, Bennett C, Manuel DG. Ascertainment of chronic diseases using population health data: a comparison of health administrative data and patient self-report. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA., Jr Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:965–971. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radeos MS, Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Barr RG, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayne ST, Buenconsejo J, Janerich DT. Previous lung disease and risk of lung cancer among men and women nonsmokers. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:13–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, Accordini S, Antonicelli L, Bugiani M, Casali L, Ferrari M, Nicolini G, Panico MG, et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardin M, Silverman EK, Barr RG, Hansel NN, Schroeder JD, Make BJ, Crapo JD, Hersh CP COPDGene Investigators. The clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthma. Respir Res. 2011;12:127. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fry AM, Shay DK, Holman RC, Curns AT, Anderson LJ. Trends in hospitalizations for pneumonia among persons aged 65 years or older in the United States, 1988–2002. JAMA. 2005;294:2712–2719. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.21.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miravitlles M, Andreu I, Romero Y, Sitjar S, Altés A, Anton E. Difficulties in differential diagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e68–e75. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X625111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmond K, Scott S, Korczak V, Ward C, Sanderson C, Theodoratou E, Clark A, Griffiths U, Rudan I, Campbell H. Long term sequelae from childhood pneumonia; systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli BR, Criner G, Curtis JL, Fabbri LM, Goldin JG, Jones PW, Macnee W, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:598–604. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1843CC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu AH, Fontham ET, Reynolds P, Greenberg RS, Buffler P, Liff J, Boyd P, Henderson BE, Correa P. Previous lung disease and risk of lung cancer among lifetime nonsmoking women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:1023–1032. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner MC, Chen Y, Krewski D, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with lung cancer mortality in a prospective study of never smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:285–290. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1792OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azad N, Rojanasakul Y, Vallyathan V. Inflammation and lung cancer: roles of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008;11:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10937400701436460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell HA, Iyen-Omofoman B, Baldwin DR, Hubbard RB, Tata LJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk of lung cancer: the importance of smoking and timing of diagnosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:e34–e35. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828950e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberger A, Bickeböller H, McCormack V, Brenner DR, Duell EJ, Tjønneland A, Friis S, Muscat JE, Yang P, Wichmann HE, et al. Asthma and lung cancer risk: a systematic investigation by the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:587–597. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Zein M, Parent ME, Kâ K, Siemiatycki J, St-Pierre Y, Rousseau MC. History of asthma or eczema and cancer risk among men: a population-based case–control study in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang HY, Li XL, Yu XS, Guan P, Yin ZH, He QC, Zhou BS. Facts and fiction of the relationship between preexisting tuberculosis and lung cancer risk: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2936–2944. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan YG, Jiang Y, Chang RS, Yao SX, Jin P, Wang W, He J, Zhou QH, Prorok P, Qiao YL, et al. Prior lung disease and lung cancer risk in an occupational-based cohort in Yunnan, China. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung CC, Lam TH, Yew WW, Law WS, Tam CM, Chang KC, McGhee S, Tam SY, Chan KF. Obstructive lung disease does not increase lung cancer mortality among female never-smokers in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:546–552. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsson AC, Gustavsson P, Kromhout H, Peters S, Vermeulen R, Brüske I, Pesch B, Siemiatycki J, Pintos J, Brüning T, et al. Exposure to diesel motor exhaust and lung cancer risk in a pooled analysis from case–control studies in Europe and Canada. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:941–948. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0940OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]