To the Editor:

Mechanotransduction is increasingly appreciated as being relevant to cell activation. This is pertinent to asthma, in which airway smooth muscle contraction, leading to bronchoconstriction, compresses airway epithelial cells. Several studies have shown that compressive force comparable with that arising in vivo, with bronchoconstriction, promotes bronchial epithelial cell activation in vitro, with generation and release of growth factors and cytokines (1, 2). We have demonstrated the relevance of mechanotransduction to asthma in vivo, with repeated bronchoconstriction inducing epithelial activation and promoting airway remodeling changes (3). These findings are supported by ex vivo work demonstrating up-regulation of contractile proteins and the activation of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) after airway narrowing (4). It is, however, unclear whether epithelial responses to bronchoconstriction reflect a normal airway response to mechanotransductive stimuli or whether there is an altered response in asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells.

The epithelium in asthma is structurally and functionally abnormal, with increased production of mucus, higher permeability, a greater sensitivity to oxidants, and a deficient innate immune response to virus (5, 6). Interaction of an abnormal epithelium in asthma with underlying mesenchyme may result in deviation of immune, inflammatory, and structural responses down abnormal pathways in response to external stimuli (7). Although response to compression has not been assessed in asthmatic epithelial cells, an abnormal response to physical stress may provide an additional pathway for asthma pathogenesis.

We hypothesized that mature primary bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) cultured in vitro from volunteers with and without asthma would respond similarly to a compressive stimulus mimicking bronchoconstriction and that the epithelial response to bronchoconstriction in vivo was a normal response to this stimulus.

To test this hypothesis, BECs were obtained by brushings at bronchoscopy from adult volunteers, both with and without a diagnosis of asthma, to establish primary epithelial cell cultures. Patients with asthma (n = 13) had a physician diagnosis of asthma and had either a provocative concentration of methacholine, causing a 20% fall (PC20) in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second of less than 8 mg/ml, or were receiving high-dose maintenance inhaled corticosteroids. Healthy volunteers (n = 11) had no respiratory disease and a methacholine PC20 higher than 16 mg/ml (see online supplement). All participants gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the local research ethics committee. BECs were cultured and taken to an air–liquid interface (ALI) at passage 2, as previously described (5, 6). Cultures were used at ALI day 21 when confluent and when the transepithelial resistance was greater than 3,000 Ω ⋅ cm2. Sixteen hours before compression, ALI medium was replaced with minimal medium, comprising a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium and bronchial epithelial basal medium plus insulin, transferrin, penicillin, and streptomycin. Cell compression was performed by increasing air pressure above the ALIs to 30 cm H2O pressure, using humidified 5% CO2 in air for 1 hour (1, 2). Cells were also subject to sham compression. Basal medium was analyzed 24 hours after compression. Two transwells from each volunteer were used in each of the sham and compression groups of the study. Total TGF-β ELISA (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) and bead-based multiplex analysis (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) were performed on basal medium to manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

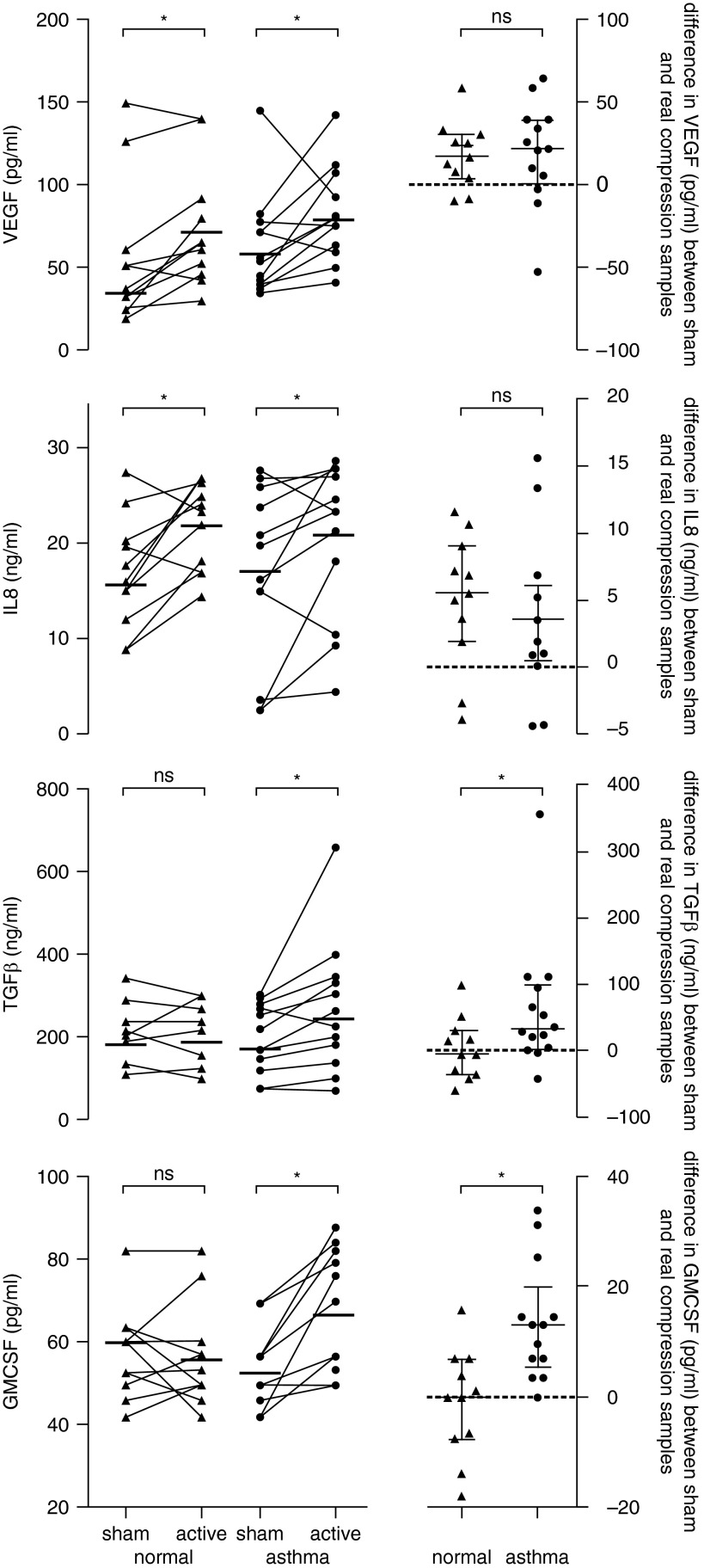

There were no differences in mediator measures between the groups with and without asthma after sham compression. Interleukin 8 (IL-8) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were significantly increased after compression in both normal and asthma-derived cells, whereas TGF-β and granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were only increased after compression of cells derived from donors with asthma, with this difference being significant within and between groups (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Results of Compression of Air–Liquid Interface Cultures from Normal Subjects and Patients with Asthma

| Normal |

Asthma |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham Compression | Active Compression | Change | P Value for Within-Group Change | Sham Compression | Active Compression | Change | P Value for Within-Group Change | P Value for Between-Group Change | |

| VEGF, pg/ml | 38.2 (26.1 to 61.5) | 63.5 (45.7 to 92.2) | 17.2 (4.1 to 30.7) | 0.014 | 54.3 (40.0 to 75.6) | 75.1 (62.1 to 100.2) | 22.1 (1.2 to 39.6) | 0.039 | 0.64 |

| IL-8, ng/ml | 15.94 (11.89 to 20.28) | 23.37 (16.96 to 26.15) | 5.53 (1.94 to 9.06) | 0.014 | 19.71 (9.13 to 26.06) | 23.23 (14.24 to 27.44) | 3.52 (0.48 to 6.04) | 0.048 | 0.27 |

| TGF-β, ng/ml | 191.9 (120.0 to 231.6) | 211.2 (119.1 to 266.7) | −4.3 (−35.4 to 29.8) | 1.00 | 163.1 (89.7 to 266.9) | 218.8 (111.5 to 330.1) | 35.0 (10.4 to 103.1) | 0.011 | 0.03 |

| GM-CSF, pg/ml | 60.1 (49.6 to 63.3) | 53.2 (49.4 to 60.1) | 0.0 (−7.3 to 7.1) | 0.81 | 49.6 (47.6 to 56.7) | 69.9 (55.0 to 80.5) | 13.1 (5.4 to 20.0) | 0.002 | 0.002 |

Concentrations of cytokines in basal media from primary bronchial epithelial cells after compression for 1 hour at 30 cm H2O pressure. All measurements are expressed as median (interquartile range). P values within group were calculated by Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the difference in the change between asthma and normal cells calculated using Mann-Whitney U testing.

Definition of abbreviations: GM-CSF = granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor; IL8 = interleukin 8; TGF-β = transforming growth factor beta; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 1.

Cytokine release into the basolateral medium of air–liquid interface cultures from donors with and without asthma 24 hours after apical compression with 5% CO2 in air at 30 cm H2O pressure for 1 hour. GMCSF = granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor; IL-8 = interleukin 8; ns = not significant; TGF-β = transforming growth factor β; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor. Bars indicate median values and interquartile ranges. *P < 0.05, calculated using Wilcoxon signed-rank test within groups and the difference in the change between asthma and normal cells using Mann-Whitney U testing.

Discussion

We identified no difference between asthmatic and healthy epithelial cells in the basal output of IL-8, VEGF, GM-CSF, or TGF-β, consistent with other publications, but did reveal the differing potential of asthmatic and healthy BECs to respond to compressive force. We demonstrate that bronchial epithelial cell responses to mechanical compressive stress are a normal physiological mechanism, with similar release of IL-8 and VEGF from healthy and asthma-derived cells, whereas TGF-β and GM-CSF concentrations in basal medium only increased after mechanical compression of cells from individuals with asthma. This is the first study demonstrating a differential response of asthmatic and normal BECs to mechanical compression.

The reason for the additional response in asthmatic cells is currently unclear, but in comparison with healthy airway epithelium, the asthmatic epithelium is morphologically distinct, with reduced expression of adhesion molecules including E-cadherin and ZO-1 and increased expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (8, 9). During apical compression of epithelial cells, there is a reduction in the volume of the lateral intercellular space, leading to increased activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (2, 10, 11). Potentially, this pathway underlies the additional TGF-β responses to compression we observed. In our study, compression did not lead to increased TGF-β release from normal cells, although this has previously been described (2). The ALI culture duration (day 10–14, rather than at day 21 in our study) and the small numbers of donors (1, 2) used previously may explain the discrepancy in the observed results. We were unable to identify any significant correlation between clinical measures of asthma (PC20 to methacholine, percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second, or reversibility) and change in TGF-β or GM-CSF concentrations with compression.

TGF-β and GM-CSF release after airway compression may contribute to epithelial mast cell and eosinophil recruitment, both of which are features of the asthmatic disease process (12, 13). In addition, TGF-β, through mesenchymal signaling, is likely to promote myofibroblast transformation and enhance collagen synthesis and subbasement membrane collagen deposition, as well as induce increased smooth muscle contractile protein expression (4, 14), all features of airway wall remodeling. Epithelial VEGF and IL-8 release has relevance in asthma with regard to angiogenesis and neutrophil recruitment. Such release may also explain the reported airway neutrophilic inflammation and vascular remodeling described in nonasthmatic individuals with chronic cough (15).

This study provides, for the first time, a direct comparison of the response of primary epithelial cells from volunteers with and without asthma to compressive force and further adds to the weight of evidence for the relevance of airway mechanical compressive forces induced by bronchoconstriction to the asthmatic disease process.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: C.G. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. P.D. and L.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. D.D. and P.H. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council UK (G0900453) and National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre Funding Scheme.

This letter has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Park JA, Tschumperlin DJ. Chronic intermittent mechanical stress increases MUC5AC protein expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:459–466. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0195OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tschumperlin DJ, Dai G, Maly IV, Kikuchi T, Laiho LH, McVittie AK, Haley KJ, Lilly CM, So PTC, Lauffenburger DA, et al. Mechanotransduction through growth-factor shedding into the extracellular space. Nature. 2004;429:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature02543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grainge CL, Lau LCK, Ward JA, Dulay V, Lahiff G, Wilson S, Holgate S, Davies DE, Howarth PH. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2006–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oenema TA, Maarsingh H, Smit M, Groothuis GMM, Meurs H, Gosens R. Bronchoconstriction Induces TGF-β Release and Airway Remodelling in Guinea Pig Lung Slices. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucchieri F, Puddicombe SM, Lordan JL, Richter A, Buchanan D, Wilson SJ, Ward J, Zummo G, Howarth PH, Djukanović R, et al. Asthmatic bronchial epithelium is more susceptible to oxidant-induced apoptosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:179–185. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.2.4699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedorov IA, Wilson SJ, Davies DE, Holgate ST. Epithelial stress and structural remodelling in childhood asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:389–394. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grainge CL, Davies DE. Epithelial injury and repair in airways diseases. Chest. 2013;144:1906–1912. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puddicombe SM, Torres-Lozano C, Richter A, Bucchieri F, Lordan JL, Howarth PH, Vrugt B, Albers R, Djukanovic R, Holgate ST, et al. Increased expression of p21(waf) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in asthmatic bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:61–68. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 2007;447:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Even-Tzur N, Kloog Y, Wolf M, Elad D. Mucus secretion and cytoskeletal modifications in cultured nasal epithelial cells exposed to wall shear stresses. Biophys J. 2008;95:2998–3008. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinken TM, Thijssen DHJ, Hopkins N, Black MA, Dawson EA, Minson CT, Newcomer SC, Laughlin MH, Cable NT, Green DJ. Impact of shear rate modulation on vascular function in humans. Hypertension. 2009;54:278–285. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tschumperlin DJ, Shively JD, Kikuchi T, Drazen JM. Mechanical stress triggers selective release of fibrotic mediators from bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:142–149. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0121OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choe MM, Sporn PHS, Swartz MA. An in vitro airway wall model of remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L427–L433. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00005.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niimi A. Structural changes in the airways: cause or effect of chronic cough? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]