Abstract

Importance

Payments around episodes of inpatient surgery vary widely among hospitals. As payers move towards bundled payments, understanding sources of variation– including use of medical consultants –is important.

Objective

To describe the use of medicine consultations for hospitalized surgical patients, factors associated with utilization, and practice variation across hospitals.

Design

Observational retrospective cohort study of fee-for-service Medicare patients undergoing colectomy or total hip replacement (THR) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 at US acute care hospitals.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Number of inpatient medical consults.

Results

More than half of patients undergoing colectomy (91,684) or THR (339,319) received at least one medicine consult while hospitalized (69% and 63% respectively). Median consultant visits from a medicine physician were 9 for colectomy, and 3 for THR. The likelihood of having at least one medicine consult varied widely among hospitals (IQR: 50% to 91% for colectomy; IQR: 36% to 90% for THR). For colectomy, settings associated with greater use included non-teaching (ARR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.26), and for-profit (ARR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.20). Variation in use of medical consultations was greater for colectomy patients without complications (IQR: 47% to 79%), compared to those with complications (IQR: 90% to 95%). Results stratified by complications were similar for THR.

Conclusions and Relevance

The use of medicine consults varied widely across hospitals, particularly for surgical patients without complications. Understanding the value of medicine consults will be important as hospitals prepare for bundled payments and strive to enhance efficiency.

Introduction

As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and others move to bundled payments around longitudinal episodes of care, hospitals are facing a greater need to understand practice variation and areas of excess resource use within episodes of care. In the case of inpatient surgery, for example, one recent study suggests that episode-based payments for surgery vary as much as 10% to 40% after adjusting for case mix and price.1 For some procedures, variation in episode-based payments is driven by multiple factors, including readmissions, use of home health, skilled nursing services, and other components of post-discharge care.12

Another source of variation is the use of professional services, including the use of medical consultants. Internists and medical sub-specialists are frequently called upon to provide pre-operative assessments of risk, and to provide advice on how to reduce these risks. Medical consultants may also be employed for more routine co-management, caring for surgical patients’ chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension for the duration of the hospital stay. Finally, medical consultants often assist in the care of patients with certain complications after surgery, including acute kidney injury, surgical site infections, and post-operative myocardial infarction.

Although prior work suggests a long-term trend towards increased use of medical consultants for co-management of surgical patients,3 variation in the use of consults for hospitalized surgical patients has not been studied carefully. In this context, we used national Medicare data to explore the use of medicine consultations around inpatient surgery, factors associated with increased utilization, and variation in practice patterns across hospitals.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

To identify inpatient medical visits, we used the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) File and the Carrier File (100% for our cohort). We also used the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey 2007 to identify hospital characteristics.

From these complete Medicare claims data, we created a cohort of elderly fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who underwent colectomy or total hip replacement (THR) at a non-federal hospital from January 2007 to December 2010. We chose to examine these two procedures because they are among the top 10 principal surgical procedures performed on Medicare patients. Colectomy is also performed on patients likely to have multiple medical co-morbidities that may be managed with or without a medical consultant. Total hip replacement is one of the procedures included in CMS’ bundled payment demonstration project.4

We used procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, version 9 to define colectomy (procedure codes: 45.73–45.76, 45.79, and 45.81–45.83) and THR (procedure code 81.51), identifying 497,655 colectomy patients and 567,646 THR patients. We excluded patients admitted to facilities other than general acute care hospitals for these index procedures and those admitted to hospitals we could not link to AHA data. We also excluded patients not enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service Parts A and B for the duration of their hospitalizations, and patients less than 65 years of age or older than 99 years of age at the time of their procedure.

To increase the clinical homogeneity of our samples, we applied several additional exclusion criteria. We excluded colectomy patients with no cancer diagnosis (i.e., diagnosis codes: 153.0–153.9 and 154.0) and THR patients with a hip fracture diagnosis (i.e., diagnosis codes: 820.0–820.3, 820.8, and 820.9). Finally, we excluded patients whose inpatient stays spanned two calendar years because we did not have complete claims data for these patients (2,975 patients for colectomy, 1,752 patients for THR).

To increase the reliability of our estimates and because hospitals varied widely in the number of procedures performed during the study period (i.e., range of 1 to 446 for colectomy, and range of 1 to 5,084 for THR), we also excluded patients if their hospitals had fewer than 10 cases in any year during our study period. Similar exclusion criteria have been chosen in prior studies to reduce statistical artifact.5 Two thousand one hundred eighty-six hospitals with 48,306 patients performed fewer than 10 colectomies per year during the study period; 1,321 hospitals with 32,434 patients performed fewer than 10 THRs per year during the study period. After applying all exclusion criteria, our final analytic samples included 91,684 patients who underwent colectomy at 930 hospitals, and 339,319 patients who underwent THR at 1,589 hospitals.

Characterizations of Medical Consultations

Our primary outcome was having at least one inpatient medical consult at any time during hospitalization for colectomy or THR. We defined inpatient consultations using CPT codes (99221–99223, 99291–99292, 99251–99255, and 99231–99233). In most cases, these codes do not allow us to distinguish between an attending vs. consulting medicine physician. In defining inpatient consultations for our cohort, we included all of these codes, because clinical practice and Medicare coding regulations make little distinction between care for a surgical inpatient that is provided by an attending vs. consulting medicine physician. We included consults that had been performed by providers in general medicine (general practice, family practice, internal medicine, or geriatric medicine), oncology (medical oncology or hematology oncology), cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, infectious disease, nephrology, physical medicine & rehabilitation, pulmonary disease and/or critical care, or other medical sub-specialties (allergy & immunology, dermatology, hematology, neurology, pain management, or rheumatology).

Using a previously validated methodology,6,7 we defined eight common postoperative, inpatient surgical complications with ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes (see Appendix). These post-operative complications were: pulmonary failure, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, hemorrhage, surgical site infection, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Statistical Analyses

We first characterized the types of consults ordered for patients undergoing colectomy or total hip replacement (THR). For each specialty type, we identified the proportion of patients with at least one consult and the median number of visits observed when at least one consult had been ordered. We also described the proportion of patients who received medical co-management (using the previously validated definition of 70% or more of inpatient days with an evaluation and management claim from a medicine physician).3

Hierarchical logistic regression analyses were used to identify patient and hospital factors associated with ordering at least one peri-operative medical consult (binary outcome). Specifically, we used generalized linear mixed model (GLMMIX) with logit link to account for the clustering of patients within hospitals while assessing the effect of patient characteristics (gender, age group, race, number of comorbidities, elective admission type) and hospital characteristics [hospital beds (500+,350 to 499, 200 to 349, <200); teaching (defined as membership in the Council of Teaching Hospitals); registered nurse-to-census ratio (ratio of full-time equivalent registered nurses to total inpatient days); percent Medicaid days (ratio of total facility Medicaid days to total facility inpatient days, multiplied by 100); rural; profit status (for-profit, non-profit, other); and region (South, Northeast, West, Midwest)]. In addition to the patient and hospital fixed effects, our model also included a random hospital-specific intercept to capture the unmeasured heterogeneity across hospitals. Let Yij =1, if for the jth patient seen at the ith hospital at least one peri-operative medical consult was ordered, and Yij = 0 otherwise. The probability of at least one peri-operative medical consult for the jth patient seen at the ith hospital can then be modeled as follows:

where β00 is the population-averaged log-odds of at least one peri-operative medical consult, β0i is the hospital-specific random effect, assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and variance σ2hosp, Xij is the matrix of patient covariates, θ is the corresponding vector of fixed effects representing changes in the log-odds of medical consult use corresponding to each unit change in the covariate values, Zi represents the vector of hospital-level covariates for the ith hospital, and γ is the corresponding vector of coefficients. Model estimates were obtained using a penalized quasi-likelihood based approach. Adjusted risk ratios based on the model were calculated to aid in the interpretability and intuitiveness of the results.8

We also explored hospital variation in medicine consult use. We were particularly interested in how practices might vary after accounting for complications or elective admission type. For each condition (i.e., colectomy and THR), we fitted a hierarchical logistic regression for the entire patient cohort. We then fitted models stratified by the presence or absence of complications or by elective status. Covariates in the overall group model were age, sex, race, and number of comorbidities. The models stratified by complications included elective status as an additional covariate.

Hospital-specific rates of the presence of at least one medical consult among all patients were obtained using empirical Bayes predictions and then plotted by hospital rank, from lowest to highest according to the empirical Bayes predictions. This method shrinks the estimate of the hospital-specific medical consult rate towards the average rate, as a factor of the number of patients treated at the hospital. Hospitals treating a large number of patients will have less shrinkage whereas hospitals treating a small number of patients will have more shrinkage towards the average rate. To display hospital variation in consult use stratified by complications or elective admission type, we used box plots with +/− 1.5 times the interquartile range as whiskers, and points for outliers.

Describing variation in use of visits by medicine physicians is the first step towards understanding when these visits have value for surgical patients. In exploratory analyses, we therefore examined the association between medicine consults and two outcomes: 30-day mortality (defined as death within 30 days of admission), and the presence of one or more post-operative complications during the hospitalization (as defined earlier). For colectomy and THR, we fitted logit regression models with these outcomes as dependent variables. Covariates in these models were age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, and elective status. For each patient, we used these model results to generate (adjusted) predicted probabilities of mortality and one or more complications. We then computed average predicted probabilities at the hospital level both with and without application of the Bayesian shrinkage method we describe above. We also computed average (unadjusted), hospital-level measures of inpatient medical visit use (one or more visits vs. none) and grouped hospitals into quintiles according to these visit-based averages. We report average hospital-level predicted mortality and complications outcomes by visit-use quintile.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two-sided tests were used, with p-values <0.05 considered statistically significant. This study is part of a larger project that was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and found to be exempt from its oversight.

Results

Among colectomy patients, 50% had at least one visit by a general medicine consult (Table 1), and about one-third were co-managed by a generalist (results not displayed). Fifty-six percent of colectomy patients saw at least one medical specialist, most commonly a cardiologist (28%), oncologist (25%), or gastroenterologist (22%). Sixty-nine percent of colectomy patients saw at least one medicine consultant (generalist or specialist), and for this group of patients, the median number of visits by any consultant was nine, and the median number of specialists seen was two.

Table 1.

Proportion of Surgical Patientsa Receiving Medicine Visits, by Procedure and Visit Type

| Medicine Visit Type | Colectomy (n = 91,684) |

Total Hip Replacement (n =

339,319) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with visits | Visits, when present | % with visits | Visits, when present | |||

| Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | |||

| General Medicine | 50 | 7 | (4 to 12) | 53 | 3 | (2 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Medical Specialist | 56 | 6 | (2 to 12) | 24 | 2 | (1 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Cardiology | 28 | 4 | (2 to 8) | 8 | 2 | (2 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Oncology | 25 | 2 | (1 to 4) | 1 | 2 | (1 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Gastroenterology | 22 | 3 | (2 to 5) | 1 | 2 | (1 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Pulmonary &/or Critical Care | 19 | 5 | (3 to 9) | 4 | 3 | (2 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Nephrology | 7 | 5 | (3 to 9) | 2 | 3 | (2 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Infectious Diseases | 6 | 5 | (3 to 9) | 1 | 3 | (2 to 5) |

|

| ||||||

| Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | 4 | 1 | (1 to 2) | 11 | 1 | (1 to 2) |

|

| ||||||

| Endocrinology | 2 | 4 | (2 to 8) | 1 | 2 | (1 to 4) |

|

| ||||||

| Any Otherb | 5 | 2 | (1 to 4) | 2 | 2 | (1 to 3) |

|

| ||||||

| Any Medical Visit(Generalist or Specialist) | 69 | 9 | (4 to 19) | 63 | 3 | (2 to 5) |

Abbreviations: n is number of patients.

Proportion of surgical patients for which each type of physician visited at least once.

Any Other includes dermatology, allergy & immunology, neurology, rheumatology, pain management, and hematology.

Fifty-three percent of patients who underwent THR had a general medicine consult (Table 1), and about one-third were co-managed by a generalist (results not displayed). However, compared with colectomy, many fewer THR patients received at least one specialist consult (24%), with the most common specialist consult type being physical medicine & rehabilitation (11%). Among THR patients who saw at least one medicine consultant (generalist or specialist), the median number of visits by any consultant was three, and the median number of specialists seen was one.

In adjusted analyses, patient factors associated with ordering at least one medicine consult for patients undergoing either procedure included older age, more comorbidities, and non-elective admission type (Table 2). For both procedures, hospital factors associated with ordering at least one medicine consult included being located in the Midwest. Non-teaching status and for-profit status were also associated with greater use of medicine consults for colectomy patients. Larger hospital size was associated with greater use of medicine consults for THR patients.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Ordering at Least One Medicine Visit, Adjusteda

| Characteristics | Colectomy |

Total Hip Replacement |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or Mean | ARR (95% CI) | % or Mean | ARR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||

|

| ||||

| Female | 55.0 | Ref. | 62.3 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| Male | 45.0 | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 37.7 | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) |

|

| ||||

| Age group, years | ||||

|

| ||||

| 65–69 | 16.0 | Ref. | 23.6 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| 70–74 | 19.0 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 25.3 | 1.06 (0.96–1.18) |

|

| ||||

| 75–79 | 21.7 | 1.08 (0.99–1.16) | 23.8 | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) |

|

| ||||

| ≥80 | 43.4 | 1.18 (1.09–1.28) | 27.3 | 1.24 (1.12–1.38) |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

|

| ||||

| White | 88.3 | Ref. | 94.0 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| Black | 8.2 | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 4.1 | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) |

|

| ||||

| Others | 3.5 | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 1.9 | 1.00 (0.89–1.11) |

|

| ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||

|

| ||||

| Zero | 6.9 | Ref. | 12.3 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| One | 21.7 | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 30.3 | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) |

|

| ||||

| Two or more | 71.4 | 1.43 (1.29–1.57) | 57.3 | 1.46 (1.29–1.66) |

|

| ||||

| Elective admission type | 65.1 | 0.67 (0.62–0.73) | 93.3 | 0.83 (0.76–0.92) |

|

| ||||

| Beds | ||||

|

| ||||

| <200 | 10.3 | Ref. | 26.2 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| 200–349 | 33.8 | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) | 31.6 | 1.11 (1.00–1.24) |

|

| ||||

| 350–499 | 24.9 | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | 18.5 | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) |

|

| ||||

| ≥500 | 31.0 | 1.04 (0.94–1.14) | 23.7 | 1.14 (1.02–1.28) |

|

| ||||

| Teaching status | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 23.3 | Ref. | 20.1 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| No | 76.7 | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 79.9 | 1.14 (1.00–1.31) |

|

| ||||

| Nurse ratiob | 6.7 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 7.2 | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) |

|

| ||||

| % Medicaid daysb | 15.4 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 14.7 | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) |

|

| ||||

| Location | ||||

|

| ||||

| Urban | 90.1 | Ref. | 90.5 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| Rural | 9.9 | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) | 9.5 | 0.90 (0.79–1.03) |

|

| ||||

| Profit status | ||||

|

| ||||

| Non-profit | 84.7 | Ref. | 80.7 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| For-profit | 7.2 | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 10.9 | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) |

|

| ||||

| Other | 8.1 | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 8.4 | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) |

|

| ||||

| Region | ||||

|

| ||||

| South | 39.8 | Ref. | 34.4 | Ref. |

|

| ||||

| Northeast | 20.7 | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 19.2 | 1.08 (0.97–1.21) |

|

| ||||

| West | 12.6 | 0.98 (0.90–1.08) | 17.9 | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) |

|

| ||||

| Midwest | 26.9 | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 28.5 | 1.18 (1.06–1.32) |

Abbreviations: ARR is adjusted risk ratio, CI is confidence interval, and Ref. is reference.

Multivariable model adjusted for gender, age group, race, count of comorbidities, elective status, beds, teaching, nurse ratio (full-time registered nurses to total inpatient days * 1000), percent Medicaid days [(total facility Medicaid days/total facility inpatient days) * 100], rural, profit status, and region.

Adjusted risk ratios estimated with “unexposed” group at median among patients (nurse ratios 6.4 for colectomy, 6.8 for THR; percent Medicaid days 15% for colectomy, 14% for THR) and “exposed” group at 75th percentile among patients (nurse ratios 7.7 for colectomy, 8.1 for THR; percent Medicaid days 20% for colectomy, 19% for THR).

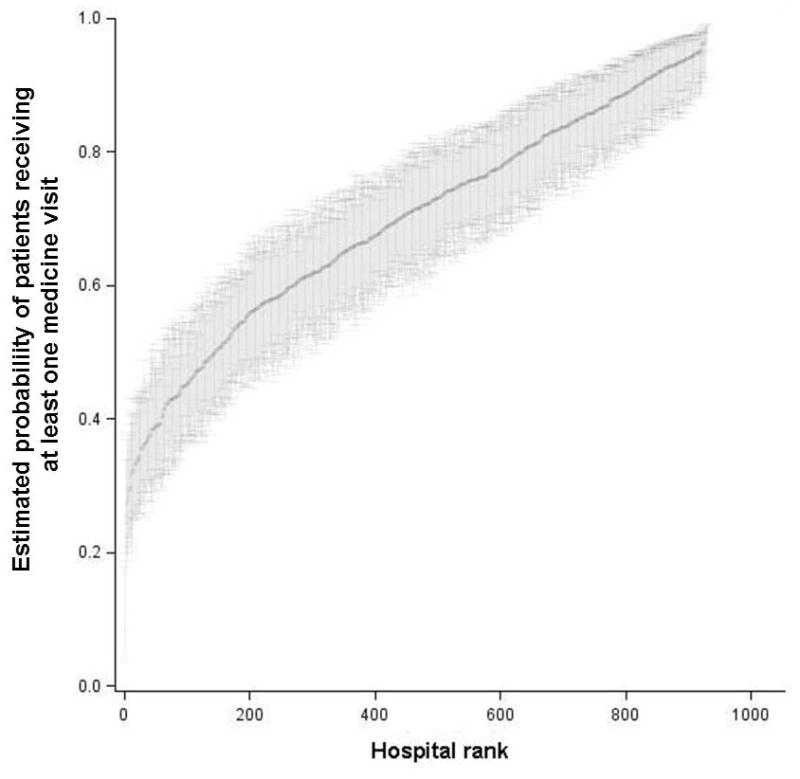

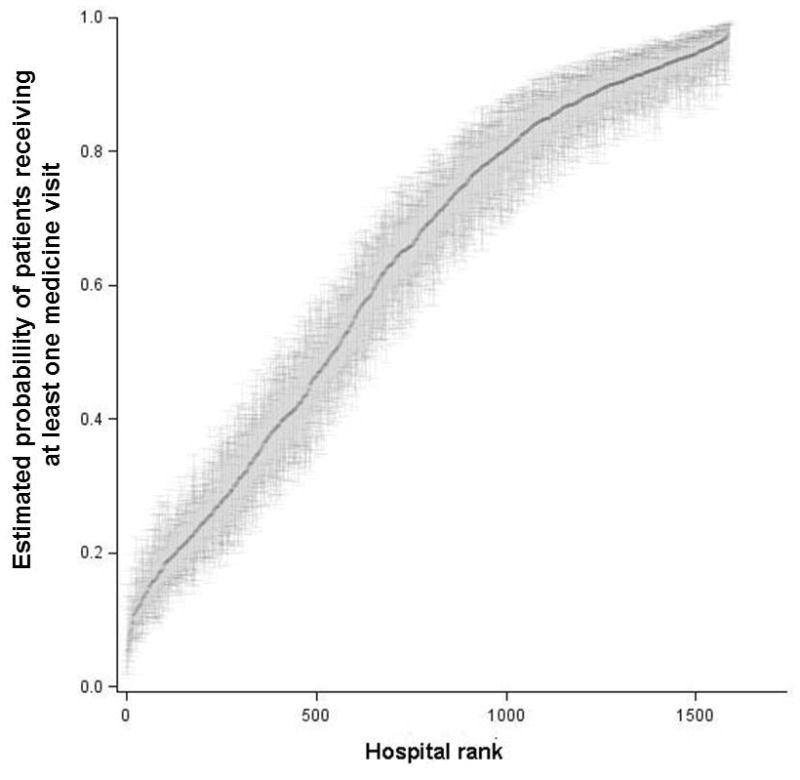

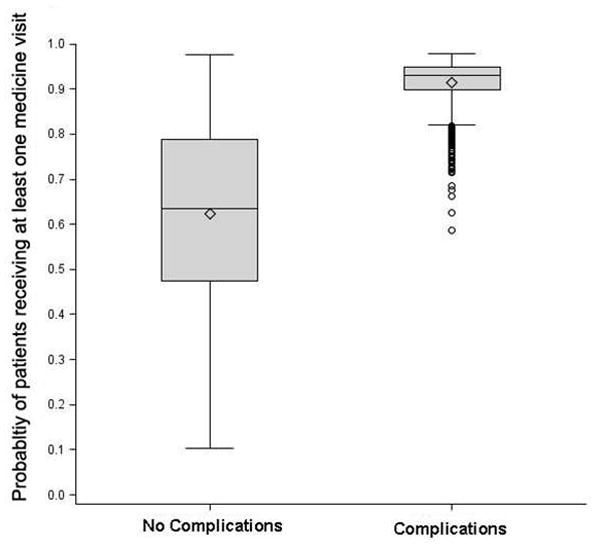

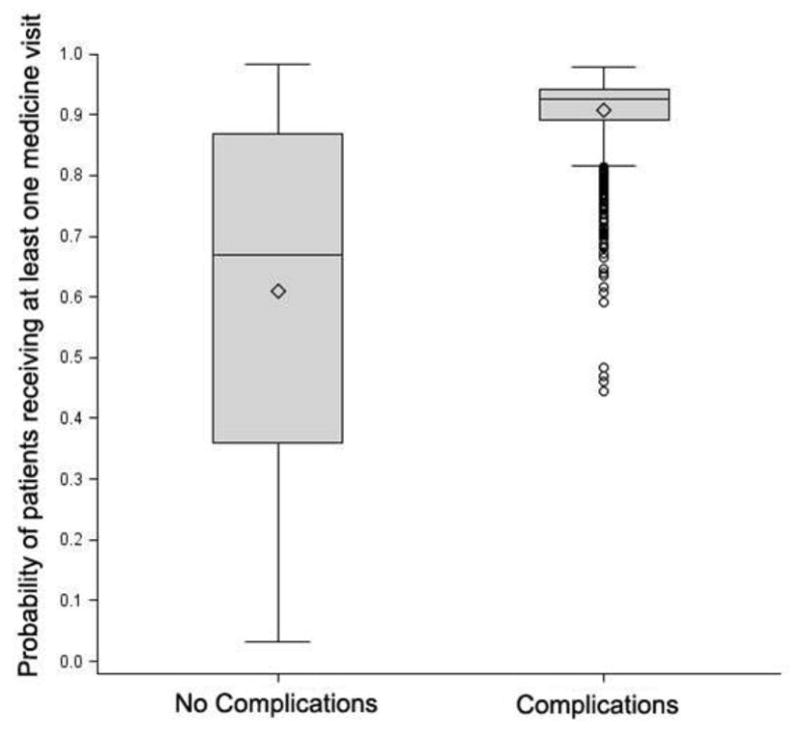

The likelihood of ordering at least one medicine consult varied widely among hospitals performing colectomy (IQR: 50% to 91%; range: 3% to 100%) or THR (IQR: 36% to 90%; range: 1% to 100%) (Figures 1A and 1B). Hospital variation in use of medicine consults was much wider for colectomy patients without vs. with a complication (IQR among those without complications: 47% to 79% vs. those with complications: 90% to 95%) (Figure 2A). Results were similar for THR (IQR among those without complications: 36% to 87% vs. those with complications: 89% to 94%) (Figure 2B). Similarly, for both colectomy and THR, variation was wider among elective compared to non-elective patients (see Appendix).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Hospital-level Probability of Colectomy Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit

Hospitals are ranked along the x-axis according to their estimated probability of having at least one medicine visit for colectomy patients. Each point of the black line represents the estimated probability for one hospital. The gray area above and below each point represents the 95% confidence interval around the estimate for each hospital.

Figure 1B. Hospital-level Probability of Total Hip Replacement Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit

Hospitals are ranked along the x-axis according to their estimated probability of having at least one medicine visit for total hip replacement patients. Each point of the black line represents the estimated probability for one hospital. The gray area above and below each point represents the 95% confidence interval around the estimate for each hospital.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Hospital-level Probability of Colectomy Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Complications

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.

Figure 2B. Hospital-level Probability of Total Hip Replacement Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Complications

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.

In exploratory analyes, the use of medicine consults was not associated with predicted, risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates for colectomy or THR. At hospitals in the lowest quintile of medicine consults for colectomy patients, the 30-day mortality rate was 4.7%. At hospitals in the highest quintile of medicine consults for colectomy patients, the 30-day mortality rate was 5.9%. However, the trend across quintiles was not statistically significant (p-value=0.40). In contrast, greater use of medicine consults was associated with the predicted presence of at least one post-operative complication. At hospitals in the lowest (vs. highest) quintile of medicine consults for colectomy patients, 24.5% (vs. 28.5%) had at least one post-operative complication (p-value<0.001). Results were similar for THR, and with shrunken estimates.

Discussion

We found that use of inpatient peri-operative medical consults for two major operative procedures was common, but varied widely across hospitals. More than half of patients undergoing colectomy or THR had at least one inpatient medicine consult. Among those patients who had at least one medicine consult, the median number of visits was high −9 for colectomy and 3 for THR. Variation in use of medical consultants was wider among patients without complications, compared to patients with complications.

Prior research on peri-operative inpatient medicine consults has examined what constitutes a good consult, the association of consults with outcomes, and trends in co-management. To increase the value of consults provided,9 some have sought to improve risk-prediction and guidelines for peri-operative testing and therapeutics.10–14 Others have examined outcomes associated with use of peri-operative medical consultations in a single hospital,15,16 or region.17 This work has found that medicine consult use has an inconsistent association with length of stay and resource use. Still others have used administrative data to document the trend towards increased co-management of surgical patients by internists,3 or variation in the use of pre-operative outpatient consults.18 However, we are unaware of research that describes variation in inpatient medicine consult use in a national cohort of surgical patients.

We believe our results help identify an area of potential focus for hospitals seeking to deliver higher value care in response to payment reforms such as bundled payments. Episode-based payments are currently being tested by Medicare and commercial payers. With traditional fee-for-service, hospitals, physicians, and post-acute care providers are each paid separately for their services. For example, hospitals receive a diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for the care provided to a surgical patient, but internists are paid separately for each visit made to that same patient. With bundled payments, a single lump sum is provided for all care provided during a longitudinal episode of care. Our findings of wide variation suggest the need for additional research about when medicine consults provide added value during surgical episodes of care.

In particular, our finding that medical consult use was frequent and common among patients with complications has implications for hospitals. The training and experience of internists and medical sub-specialists equips them to help manage patients with post-operative complications such as renal failure, pneumonia, or acute myocardial infarction. But are certain types of consults more strongly associated with improved outcomes? Hospitals that “fail to rescue” their surgical patients from complications have been shown to have higher operative mortality rates.19 It is plausible that carefully timed medicine consults may reduce death after complications. For example, it may be that one nephrology consult done when acute kidney injury is first recognized, may lead to better outcomes than multiple consults several days later. It is also possible that for surgical patients with multiple medical co-morbidities, an attending medicine physician that makes daily visits throughout the hospital stay will improve outcomes. Additional research on the association between mortality after complications, and the type, timing and number of medicine consults would be valuable.

Our finding of wide variation in medicine consult use for those without complications is similar to variation for several other types of medical and surgical interventions.20–22 The variation that we found suggests a lack of consensus about the value of medicine consults for relatively well patients. For patients without complications, which rate is right? It is possible that routine use of medicine consults for relatively well patients prevents poor outcomes. Routine medical co-management of patients with recognized or unrecognized diabetes may provide great benefit. For example, hyperglycemia has been associated with increased peri-operative morbidity and mortality.23 However, it is also possible that some medical consults are perfunctory “social visits” ordered for all patients and with little clinical value. Additional research is needed to identify the best use of medicine consults for patients without complications.

In general, one would expect the care provided by medicine physicians to improve outcomes for some surgical patients. However, in exploratory analyses, we found that hospitals with greater use of medicine consults have similar or worse clinical outcomes. Our preliminary results suggest the need for additional work to better understand the relationship between medical consultations and outcomes. It is possible that our findings may be explained in part by confounders such as unmeasured severity of illness (i.e., sicker patients are more likely to receive a visit from a medicine physician), hospital selection by patients (i.e., sicker patients may be more likely to undergo surgical treatment in hospitals where they expect to receive more intensive medical management), and simultaneity bias (e.g., additional medicine consults may follow the identification of a complication, or the medicine consultant may identify the complication). Future work should use more robust methodological approaches – such as propensity score-matching and instrumental variables – to address these issues.

Our study has several important limitations. First, with administrative claims data, we were unable to ascertain in any detail the clinical indications for medical consults. This precluded a better understanding of the extent to which surgeons pre-emptively order medicine consults in relatively well patients vs. address a complication with a consultation. Second, our findings may not be broadly generalizable as we examined use of medicine consults among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age or older who underwent one of two procedures. However, we chose the most relevant population for our study, as the elderly have a disproportionate number of co-morbid conditions and are most likely to suffer from complications or die after a major procedure. Third, with our data, we were unable to explore the use of pre-operative outpatient medicine consultations. Fourth, from the perspective of the hospital, medicine physicians who assist in the care of surgical patients may have value beyond any positive impact on outcomes. For example, greater use of medicine consults may allow surgeons to spend more time performing high-margin procedures. We were unable to quantify this potential effect. Fifth, the difference in median number of medicine consults for colectomy and THR patients may reflect differences in length of stay (i.e., longer hospitalizations leading to more medicine visits). However, it is also possible that additional medicine consults generate follow-up testing and contribute to longer hospitalizations. Finally, there are well-recognized limitations in the clinical specificity of administrative claims data to characterize patient risk or categorize post-operative complications.

There is a growing imperative for hospitals to increase their efficiency. Many policymakers hope that mechanisms such as accountable care organizations and episode-based bundled payments will motivate providers to reduce costs without harming quality. Medicine consults are a common component of episodes of inpatient surgical care. Our findings of wide variation in medicine consult use – particularly among patients without complications –suggests that understanding when medicine consults provide value will be important as hospitals seek to increase their efficiency under bundled payments.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Figure 1A. Hospital-level Probability of Colectomy Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Admission Type

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.

Appendix Figure 1B. Hospital-level Probability of THR Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Admission Type

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Aging (Grant No. P01AG019783-0751 to John Birkmeyer and Jonathan Skinner). It was also supported with funding from a University of Michigan MCubed grant. Lena Chen is supported by a Career Development Grant Award (K08HS020671) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We are grateful to Edward C. Norton, PhD for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We thank Natalie J. Lin, BA, for the research assistance she provided. She was compensated for her work.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: John Birkmeyer has equity interest in ArborMetrix, a company that profiles hospital quality and episode cost efficiency. The company played no role in the manuscript.

Author contributions: Dr. Chen and Mr. Wilk had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Chen, Birkmeyer, Banerjee

Acquisition of data: Chen, Birkmeyer

Drafting of the manuscript: Chen, Wilk

Revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Chen, Wilk, Thumma, Birkmeyer, Banerjee

Statistical analysis: Chen, Wilk, Thumma, Banerjee

Obtained funding: Chen, Birkmeyer

Administrative, technical or material support: N/A

Study supervision: Birkmeyer, Banerjee

References

- 1.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Large variations in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011 Nov;30(11):2107–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Baser O, Dimick JB, Sutherland JM, Skinner JS. Medicare payments for common inpatient procedures: implications for episode-based payment bundling. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1783–1795. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Feb 22;170(4):363–368. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed September 8, 2012];Medicare Acute Care Episode Demonstration for Orthopedic and Cardiovascular Surgery. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/Downloads/ACE_web_page.pdf.

- 5.Breslin TM, Morris AM, Gu N, et al. Hospital factors and racial disparities in mortality after surgery for breast and colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 20;27(24):3945–3950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994 Jul;32(7):700–715. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weingart SN, Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, et al. Use of administrative data to find substandard care: validation of the complications screening program. Med Care. 2000 Aug;38(8):796–806. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the Risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009 Feb;44(1):288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep;143(9):1753–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra V, Flanders SA, Froehlich JB, Lau WC, Eagle KA. Perioperative practice: time to throttle back. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jan 5;152(1):47–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford MK, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN. Systematic review: prediction of perioperative cardiac complications and mortality by the revised cardiac risk index. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jan 5;152(1):26–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS, Austin PC, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Non-invasive cardiac stress testing before elective major non-cardiac surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5526. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999 Sep 7;100(10):1043–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn SL, Smetana GW. Update in perioperative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Aug 21;147(4):263–270. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auerbach AD, Rasic MA, Sehgal N, Ide B, Stone B, Maselli J. Opportunity missed: medical consultation, resource use, and quality of care of patients undergoing major surgery. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2338–2344. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Beattie WS, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Outcomes and processes of care related to preoperative medical consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1365–1374. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Beattie WS, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Variation in the practice of preoperative medical consultation for major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based study. Anesthesiology. 2012 Jan;116(1):25–34. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823cfc03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 1;361(14):1368–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung KC, Shauver MJ, Yin H, Kim HM, Baser O, Birkmeyer JD. Variations in the use of internal fixation for distal radial fracture in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Dec 7;93(23):2154–2162. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.012802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Stewart AK, Koenig RJ, Birkmeyer JD, Griggs JJ. Use of radioactive iodine for thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2011 Aug 17;306(7):721–728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2008 Oct 15;300(15):1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pichardo-Lowden A, Gabbay RA. Management of hyperglycemia during the perioperative period. Curr Diab Rep. 2012 Feb;12(1):108–118. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Figure 1A. Hospital-level Probability of Colectomy Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Admission Type

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.

Appendix Figure 1B. Hospital-level Probability of THR Patients Receiving at Least One Medicine Visit, Stratified by Admission Type

The lower and upper borders of each box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The middle line of each box indicates the median, and the diamond indicates the mean. The ends of the whiskers represent (1.5)*(interquartile range), and the circles (when present) represent outliers.