Abstract

In this paper we present a new method for spatial regularization of functional connectivity maps based on Markov Random Field (MRF) priors. The high level of noise in fMRI leads to errors in functional connectivity detection algorithms. A common approach to mitigate the effects of noise is to apply spatial Gaussian smoothing, which can lead to blurring of regions beyond their actual boundaries and the loss of small connectivity regions. Recent work has suggested MRFs as an alternative spatial regularization in detection of fMRI activation in task-based paradigms. We propose to apply MRF priors to the computation of functional connectivity in resting-state fMRI. Our Markov priors are in the space of pairwise voxel connections, rather than in the original image space, resulting in a MRF whose dimension is twice that of the original image. The high dimensionality of the MRF estimation problem leads to computational challenges. We present an efficient, highly parallelized algorithm on the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). We validate our approach on a synthetically generated example as well as real data from a resting state fMRI study.

1 Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides a non-invasive measurement of cerebral blood flow in the brain that can be used to infer regions of neural activity. Traditional fMRI studies are based on measuring the response to a set of stimuli, and analysis involves testing the time series at each voxel for correlations with the experimental protocol. Recently, there has been growing interest in using resting-state fMRI to infer the connectivity between spatially distant regions. A standard approach is to use correlation between pairs of time series as a measurement of their functional connectivity. The high level of noise present in fMRI can cause errors in pairwise connectivity measurements, resulting in spurious false connections as well as false negatives.

In both task-based and resting-state fMRI the impact of imaging noise can be reduced by taking advantage of the spatial correlations between neighoring voxels in the image. A common approach used for instance in Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM)[1] is to apply a spatial Gaussian filter to smooth the signal prior to statistical analysis. However, this can lead to overly blurred results, where effects with small spatial extent can be lost and detected regions may extend beyond their actual boundaries. An alternative approach to spatial regularization that has been proposed for task activation paradigms is to use a Markov Random Field (MRF) prior [2–6], which models the conditional dependence of the signals in neighboring voxels.

In this work we propose to use MRF models in resting-state fMRI to leverage spatial correlations in functional connectivity maps. Unlike previous MRF-based approaches, which use the neighborhood structure defined by the original image voxel grid, the neighborhoods in functional connectivity must take into account the possible relationships between spatially distant voxels. Therefore, we define the neighborhood graph on the set of all voxel pairs. This results in a Markov structure on a grid with twice the dimensions of the original image data, i.e., the pairwise connectivities for three-dimensional images results in a six-dimensional MRF. The neighborhood structure is defined so that two voxels are more likely to be connected if they are connected to each other's spatial neighbors.

We combine the Markov prior on functional connectivity maps with a likelihood model of the time series correlations in a posterior estimation problem. Furthermore, we model solve for the unknown parameters of the MRF and likelihood using an Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm. In the estimation step the posterior random field is sampled using Gibbs Sampling and estimated using Mean Field theory.

In the next section we describe our MRF model of functional connectivity maps. In Section 3 we give the details of the algorithm to estimate the functional connectivity probabilities, including implementation details for the GPU solver. Finally, in Section 4 we demonstrate the advantages of our approach on a synthetically generated data set as well as on real resting-state fMRI data.

2 Markov Random Fields for Functional Connectivity

Our framework for functional connectivity is a Bayesian approach in which we estimate the posterior distribution of the connectivity between voxels, conditioned on the fMRI data. Let x = {xij} denote the functional connectivity map, i.e., a map denoting whether each pair of voxels i, j is connected, and let y denote the original fMRI data, or some meausrements derived from the fMRI. In this work we take y to be the map of correlations between pairs voxel time series. The posterior distribution is then proportionally given by

| (1) |

In this work we model P(x), the prior on the connectivity map, using a MRF, and the likelihood P(y | x) using Gaussian models of the Fisher transformed correlation values. We now give details for both of these pieces of the model.

2.1 Markov Prior

Conventional image analysis applications of MRFs [7] define the set of sites of the random field as the image voxels, with the neighborhood structure given by a regular lattice. Because we are studying the pairwise connectivity between voxels, we need to define a MRF in the higher-dimensional space of voxel location pairs. Thus, if Ω ⊂ ℤd is a d-dimensional image domain, then the sites for our connectivity MRF form the set

= Ω × Ω. Let i, j ∈ Ω be voxel locations, and let

= Ω × Ω. Let i, j ∈ Ω be voxel locations, and let

i,

i,

j denote the set of neighbors of voxel i and j, respectively, in the original image lattice. Then the set of neighbors for the site (i, j) ∈

j denote the set of neighbors of voxel i and j, respectively, in the original image lattice. Then the set of neighbors for the site (i, j) ∈

is given by

is given by

ij = ({i} ×

ij = ({i} ×

j) ∪ (

j) ∪ (

i × {j}). In other words, two sites are neighbors if they share one coordinate and their other coordinates are neighbors in the original image lattice. This neighborhood structure will give us the property in the MRF that two voxels i, j in the image are more likely to be connected if i is connected to j's neighbors or vice-versa. Equipped with this graph structure,

i × {j}). In other words, two sites are neighbors if they share one coordinate and their other coordinates are neighbors in the original image lattice. This neighborhood structure will give us the property in the MRF that two voxels i, j in the image are more likely to be connected if i is connected to j's neighbors or vice-versa. Equipped with this graph structure,

is a regular 2d-dimensional lattice, which we will refer to as the connectivity graph.

is a regular 2d-dimensional lattice, which we will refer to as the connectivity graph.

We next define a multivariate random variable x = {xij} on the set

, where each random variable xij is a binary variable that denotes the connectivity (xij = 1) or lack of connectivity (xij = – 1) between voxel i and j. If A ⊂ S, let xA denote the set of all xij with (i, j) ∈ A, and let x-ij denote the collection of all variables in x excluding xij. For x to be a MRF it must satisfy

, where each random variable xij is a binary variable that denotes the connectivity (xij = 1) or lack of connectivity (xij = – 1) between voxel i and j. If A ⊂ S, let xA denote the set of all xij with (i, j) ∈ A, and let x-ij denote the collection of all variables in x excluding xij. For x to be a MRF it must satisfy

According to the Hammersley and Clifford Theorem[8], x is Markov random field if and only if it is also a Gibbs distribution, defined as

| (2) |

where U is the energy function U(x) = Σ c∈

Vc, with potentials Vc defined for each clique c in the clique set

Vc, with potentials Vc defined for each clique c in the clique set

. The partition function Z = Σ exp(–U(x)) is a normalizing constant, where the summation is over all possible configurations of x. We use a particular form of MRF—the Ising model—a commonly used model for MRFs with binary states. In this model the energy function is given by

. The partition function Z = Σ exp(–U(x)) is a normalizing constant, where the summation is over all possible configurations of x. We use a particular form of MRF—the Ising model—a commonly used model for MRFs with binary states. In this model the energy function is given by

| (3) |

where the summation is over all edges〈ij, mn〉, i.e., all adjacent voxel pairs (i, j), (m, n) in the connectivity graph. When β > 0, this definition favors similarity of neighbors.

2.2 Likelihood Model

We now define the likelihood model, P(y | x), which connects the observed data y to our MRF. Because we are interested in the functional connectivity between pairs of voxels, we compute the correlation between the time courses of each pair of voxels, and get a correlation matrix y

= {yij}. Just as in the case of the random field x, the correlation matrix y is also defined on the 2-dimensional lattice

. Linear correlation is not the only choice for y. We can use any statistic, as long as it indicates the affinity between two voxel time series. Another possibility could be frequency domain measures, such as the coherence [9].

. Linear correlation is not the only choice for y. We can use any statistic, as long as it indicates the affinity between two voxel time series. Another possibility could be frequency domain measures, such as the coherence [9].

Before defining the full data likelihood, we start with a definition of the emission function at a single site sij ∈

. This is defined as the conditional likelihood, P(yij | xij), and is interpreted as the probability of the observed correlation, given the state of the connectivity between voxels i and j. We model the emission function as a Gaussian distribution with unknown mean and variance on the Fisher transformed correlation yij, that is,

. This is defined as the conditional likelihood, P(yij | xij), and is interpreted as the probability of the observed correlation, given the state of the connectivity between voxels i and j. We model the emission function as a Gaussian distribution with unknown mean and variance on the Fisher transformed correlation yij, that is,

| (4) |

where F denotes the Fisher transform. Notice that each correlation yij on site sij only depends on the latent variable xij on the same site, and does not depend on neighbors of xij. Therefore, the full likelihood is given by

| (5) |

3 Estimation via Expectation Maximization

Having defined the data likelihood and MRF prior in the previous section, we are now ready to describe the maximization of the posterior given by (1). For this we need to determine the model parameters, β in (3) and (μk, σk2) in (4). Rather than arbitrarily setting these parameters, we estimate them using an Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm. Exact computation of the full posterior (1) is intractable, due to the combinatorial number of terms in the partition function Z. Therefore, we instead maximize the approximate posterior given by the pseudo-likelihood function [7, 8],

| (6) |

In the E-step, the parameters are held fixed and we compute the posterior probability for each xij, and sample xij from the posterior distribution using Gibbs Sampling. We then compute the expected value of each connectivity node by Mean Field theory. After we compute the posterior of current point xij, we update xij with its expected value 〈xij〉

In the M-step, the complete data {〈x〉, y} is available, and the parameters can be estimated by maximizing the joint pseudo-likelihood given by (6) using Newton's method. After several iterations of this EM algorithm, we get parameters as our MAP estimates.

Gpu Implementation

The whole algorithm involves updating a high dimensional connectivity matrix x iteratively, and hence have high computation cost. We designed a parallel Markov random field updating strategy on graphics processing unit (GPU). The algorithm take only a few minutes compared with more than 1 hour on CPU counterpart.

To fit the algorithm into GPU's architecture, we use some special strategy. First, because GPU only support 3-dimensional array, we need to reshape x and y defined originally on higher dimensional graph by linear indexing their original subscripts. This is especially difficult for brain fMRI data because the gray matter voxels resides in a irregular 3-D lattice. Specific data structure are used for mapping between original voxel subscripts and their linear index i and j. Second, to update each site of MRF in parallel we have to make sure a site is not updated simultaneously with its neighbors, otherwise the field tends to be stuck in a checkerboard-like local maximum. Our strategy is to divide all the sites of the field into several sub-groups, such that a site is not in the same sub-group with its neighbors. We then can update the sub-group sequentially, while the data in sub-groups are updated simultaneously. The whole procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1.

MAP estimation by EM

| Require: Sample correlation matrix Y. |

| Init posterior matrix by maximizing conditional likelihood P(yij|xij). |

| while Δ{ β, μ, σ 2} > ε do |

| E step: |

| (a) Based on the current parameters, compute the posterior by (6). |

| (b) Repeatedly Do Gibbs Sampling until the field stabilize. |

(c) Based on current value of xij , iteratively compute the mean field for all nodes in

until the field stable. until the field stable. |

| M step: |

| (d) With complete data {X, Y}, estimate β , μ and σ2 by maximizing (6). |

| end while |

| return posterior matrix X. |

4 Results

Synthetic Data

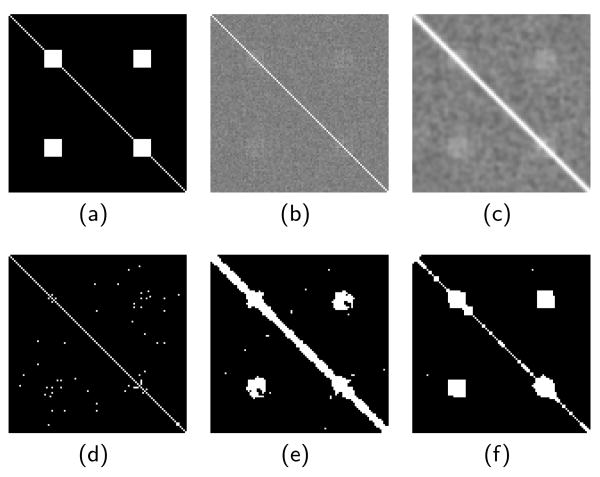

We first construct a synthetic data set consisting of a 100 × 1 1-D image, with each pixel a 300-point time course signal. The time course was constructed with a baseline DC signal of 800, plus additive Gaussian noise of variance 50. We then added a sine wave signal of frequency 0.2 and amplitude 20 to two distant regions of the image. The goal is to detect the connectivity between these two distant regions. Between those pixels containing signal the connectivity is 1, otherwise it is 0 for connectivity between signal and noise, and between noise time series. The true connectivity map is shown in Fig. 1(a)

Fig. 1.

Test of synthetic data, showing the (a) ground-truth connectivity, (b) correlation of original, noisy data, (c) correlation of Gaussian-smoothed data, (d) connectivity based on noisy correlations, (e) connectivity based on smoothed data, (f) connectivity computed using proposed MRF model.

To compare our MRF model with conventional Gaussian blurring of the correlation map, we applied both approaches to the synthetic data (Fig. 1). On the correlation map in the top row, we see smoothing does remove noise and results in a correlation map that looks more like the true connectivity map. However, it also creates several errors, most noticeably false positives around the diagonal (Fig. 1(e)). Fig. 1(f) shows the proposed MRF method better detects the true connectivity regions while removing most false positives.

Resting-State fMRI

Next we tested our method on real data from healthy control subjects in a resting-state fMRI study. BOLD EPI images (TR= 2.0 s, TE = 28 ms, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2, 40 slices at 3 mm slice thickness, 64 × 64 matrix, 240 volumes) were acquired on a Siemens 3 Tesla Trio scanner with 12-channel head coil during the resting state, eyes open. The data was motion corrected by SPM software and registered to a T2 structural image. We used a gray matter mask from an SPM tissue segmentation so that only gray matter voxels are counted in the connectivity analysis. We do not spatially smooth the data, in order to see the benefit of replacing spatial smoothing with our MRF method. Before computing the correlations, the time series at all voxels are linearly detrended by least squares regression.

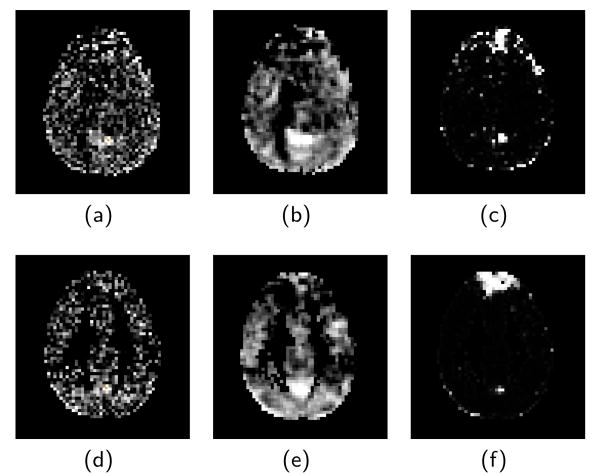

Fig. 2 compares the real data results using no spatial regularization, Gaussian smoothing, and the proposed MRF model. Though the posterior connectivity of the MRF is computed between every pair of voxels within a slice, for visualization purposes, only the posterior of the connectivity between one voxel and the slice is shown. We chose to visualize the connectivity to a voxel in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) because this is known to be involved in the Default Mode Network [10], with connections to the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). The results show that Gaussian smoothing is able to remove noise, but is unable to find a clear connection between the PCC and the MPFC. Our proposed MRF model (rightmost plot) is able to remove spurious connections, and also clearly shows a connection to the MPFC.

Fig. 2.

Correlation map and Posterior Connectivity map between seed voxel and slice containing the seed. First row is subject 1. (a) the correlation map computed from data without spatial smoothing. (b) correlation map of data after smoothing. (c) Posterior probability computed from MRF. Second row (d,e,f) is subject 2 with same test.

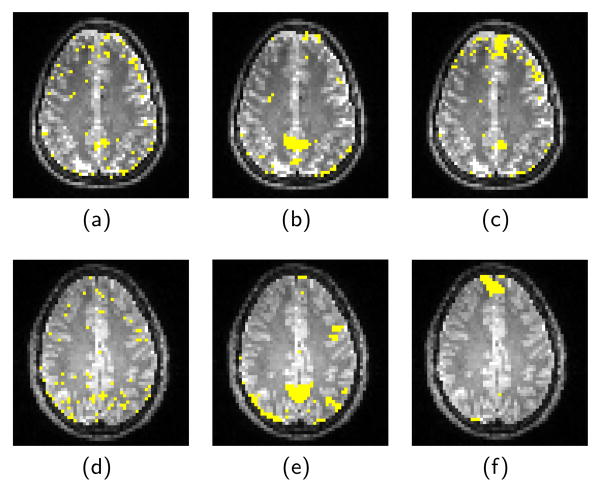

To show the strongest connections found by each method, Fig. 3 shows the thresholded connectivity maps overlaid on T2 structural image. Images in the first two columns are thresholded such that the top 5% voxel correlations are shown. For the MRF in the third column, the MAP estimate is shown.

Fig. 3.

Thresholded correlation map and Posterior Connectivity map between seed voxel and slice, overlaid to T2 image. First row is subject 1. (a) the correlation map computed from data without spatial smoothing. (b) After smoothing. (c) Posterior probability by MRF. Second row (d,e,f) is subject 2 with same test.

5 Conclusion

We propose a Markov random field and Bayesian framework for spatially regularizing functional connectivity. Future work may include running this pairwise connectivity analysis on 3D whole brain. Another interesting direction is applying the method to multiple sessions and subjects.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH Grant R01 DA020269 (Yurgelun-Todd).

References

- 1.Worsley KJ, Friston KJ. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited–again. Neuroimage. 1995;2(3):173–181. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ou W, Golland P. From spatial regularization to anatomical priors in fMRI analysis. Information in Medical Imaging. 2005:88–100. doi: 10.1007/11505730_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Descombes X, Kruggel F, Cramon DV. Spatio-temporal fMRI analysis using Markov random fields. Medical Imaging, IEEE Trans. 1998;17(6):1028–1039. doi: 10.1109/42.746636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Descombes X, Kruggel F, von Cramon DY. fMRI signal restoration using a spatio-temporal Markov random field preserving transitions. NeuroImage. 1998 Nov;8(4):340–349. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolrich M, Jenkinson M, Brady J, Smith S. Fully Bayesian spatio-temporal modeling of fMRI data. Medical Imaging IEEE Transactions on. 2004;23(2):213–231. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.823065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosman ER, Fisher JW, Wells WM. Exact MAP activity detection in fMRI using a GLM with an Ising spatial prior. MICCAI. 2004:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li SZ. Markov Random Field Modeling in Image Analysis. Springer; Mar, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besag J. Spatial interaction and the statistical analysis of lattice systems. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1974;36(2):192–236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller K, Lohmann G, Bosch V, von Cramon DY. On multivariate spectral analysis of fMRI time series. NeuroImage. 2001 Aug;14(2):347–356. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. PNAS. 98(2):676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]