Abstract

Early-onset, familial Alzheimer's disease (AD) is rare and may be attributed to disease-causinq mutations. By contrast, late onset, sporadic (non-Mendelian) AD is far more prevalent and reflects the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental risk factors, together with the disruption of epigenetic mechanisms controlling gene expression. Accordingly, abnormal patterns of histone acetylation and methylation, as well as anomalies in global and promoter-specific DNA methylation, have been documented in AD patients, together with a deregulation of noncoding RNA. In transgenic mouse models for AD, epigenetic dysfunction is likewise apparent in cerebral tissue, and it has been directly linked to cognitive and behavioral deficits in functional studies. Importantly, epigenetic deregulation interfaces with core pathophysiological processes underlying AD: excess production of Aβ42, aberrant post-translational modification of tau, deficient neurotoxic protein clearance, axonal-synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis, and cell cycle re-entry. Reciprocally, DNA methylation, histone marks and the levels of diverse species of microRNA are modulated by Aβ42, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. In conclusion, epigenetic mechanisms are broadly deregulated in AD mainly upstream, but also downstream, of key pathophysiological processes. While some epigenetic shifts oppose the evolution of AD, most appear to drive its progression. Epigenetic changes are of irrefutable importance for AD, but they await further elucidation from the perspectives of pathogenesis, biomarkers and potential treatment.

Keywords: acetylation, apoptosis, Bcl2, beta-amyloid methylation, cell cycle re-entry, HDAC, histone, inflammation, microRNA, microtubule, miR, miRNA, oxidative stress, phosphorylation, tau, secretase

Abstract

La Enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) familiar de aparición precoz, es rara y puede atríbuirse a mutaciones que causan la enfermedad. A díferencia, la EA esporádíca (no Mendelíana) de aparición tardía, es más prevalente y refleja la interacción de múltíples factores de riesgo genético y ambíental, junto con la alteración de los mecanismos epigenéticos que controlan la expresíón géníca. En consecuencia, en pacientes con EA se han documentado los pairones anormales de acetilación y metilación de hístonas, como las anormalidades en la metilación global del ADN como en la del ADN específíco del promotor, junto con la mala regulación del ARN no codíficante. En modelos de ratones transgénicos para la EA, la disfunción epígenética tambíén es evidente en el tejido cerebral, y en estudios funcionales se ha relacionado directamente con défícits cognitivos y conductuales. Es importante consíderar que la mala regulación epigenética tiene una interfase con los procesos fisíopatológicos centrales de la EA: exceso de producción de Aβ42, modificación post-translacional aberrante de tau, clearance deficiente de la proteína neurotóxica, dísfunción axonal-sináptica, apoptosís dependíente de mitocondrías y re-entrada del cíclo celular. Del mismo modo la metilación de ADN, las marcas de hístonas y los níveles de diversos tipos de mícroRAN son modulados por Aβ42, estrés oxidativo y neuroinflamación. En conclusión, los mecanismos epigenéticos están bastante mal regulados en la EA, principalmente hacía arriba, pero también hacia abajo en los procesos fisiopatológicos clave. Míentras que algunos cambíos se oponen a la evolucíón de la EA, la mayoría parece conducirla hacia su avance. Los cambios epigenéticos para la EA son de ímportancia irrefutable, pero esperan de una aclaración adicíonal desde las perspectivas de la patogénesis, los bíomarcadores y los potenciales tratamíentos.

Abstract

La forme familiale de la maladie d'Alzheimer (MA) à début précoce est rare et peut être attribuée à des mutations pathogènes. Par opposition, la forme sporadique (non mendélienne) de MA à développement tardif est beaucoup plus répandue, reflétant l'interaction de facteurs de risque multiples génétiques et environnementaux, associés à la perturbation des mécanismes épigénétiques contrôlant l'expression des gènes. C'est pourquoi des formes anormales de méthylation et d'acétylation des histones ont été documentées chez des patients atteints de MA ainsi que des anomalies de la méthylation globale et de la méthylation de l'ADN spécifique d'un gène promoteur, avec une dérégulation de l'ARN non codant. Dans des modèles de souris transgéniques pour la MA, la dysfonction épigénétique apparaissant aussi dans le tissu cérébral est directement liée aux déficits cognitifs et comportementaux dans des études fonctionnelles. De façon importante, la dérégulation épigénétique est liée aux processus physiopathologiques clés de la MA: production en excès de Aβ42, modification aberrante post-translationnelle de la protéine tau, clairance déficiente des protéines neurotoxiques, dysfonction axono-synaptique, apoptose dépendante des mitochondries et ré-entrée du cycle cellulaire. La méthylation de l'ADN, les marques d'histone et les niveaux des espèces différentes de microARN sont réciproquement modulés par l'Aβ42, le stress oxydatif et l'inflammation neuronale. Pour conduce, les mécanismes épigénétiques sont largement deérégulés dans la MA, principalement en amont mais aussi en aval des processus physiopathologiques clés. Certaines variations épigénétiques s'opposent à l'évolution de la MA mais la plupart semblent entraîner sa progression. Ces modifications, d'une importance indiscutable dans la MA, nécessitent d'être éclaircies du point de vue de la pathogenèse, des biomarqueurs et d'un traitement éventuel.

Introduction

The progressive neurodegenerative disorder, Alzheimer's disease (AD), is by far the most common cause of dementia. Early-onset AD occurs before the age of 65 and is uncommon (around 3% to 5% of cases), with late-onset AD accounting for the vast majority of patients and occurring with increasing frequency from the age of 65 onwards.1 The disorder is characterized by a profound dysfunction of cognition, together with a suite of behavioral, psychological, mood, and motor abnormalities poorly treated by currently available therapies.2,3

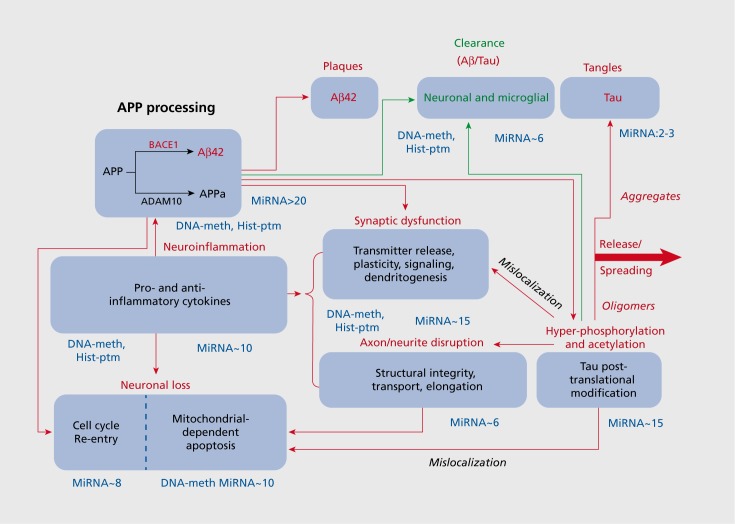

These deficits may be attributed to widespread neuronal loss, glial dysfunction, cerebrovascular damage, metabolic defects and brain atrophy, most typically—though not exclusively—in the hippocampus, temporal lobe, and eventually other regions of the neocortex.4,5 Large-scale anomalies are accompanied by, and reflect, perturbed neurotransmission, synaptic dysfunction, disruption of axonal stability and integrity, as well as the gradual propagation of cellular hallmarks of AD throughout the brain (Figure 1). These include characteristic extracellular plaques formed principally of excess β-amyloid42 (Aβ42), together with intracellular neurofibrillary tangles constituted mainly of tau following its cleavage and/or aberrant post-translational modification (PTM) by phosphorylation and acetylation.6-9 The pathological features of AD spread rostrally and intensify over the course of the disorder, which is usually classed in “Braak” stages from III/IV (mild/ moderate) to V/VI (advanced/severe).5

Figure 1. Schematic overview of core pathophysiological processes implicated in Alzheimer's disease and their modulation by epigenetic mechanisms. This depiction of core and interlinked pathophysiological processes implicated in the progression of AD provides a framework for following and integrating the roles of various epigenetic modes of regulation. The approximate number of species of miRNA implicated in modulating various mechanisms is indicated next to the respective panels. These values are likely to increase with continuing research but they are already strikingly high. In addition, it is indicated for which mechanisms a role for DNA methylation (meth) and histone post-translational modifications (PTM) has been shown. Again, this is likely to be an underestimation. Red lines and lettering indicate deleterious processes, and green ones beneficial, protective mechanisms. Note, however, that it remains under debate whether the deposition of insoluble, neurotoxic forms of excess β-amyloid42 and tau is destructive or actually protective—at least early in the disease.

Cellular mechanisms provoking these anomalies are still under clarification, but oxidative stress, energy deprivation, and neuroinflammation are considered to be key processes that trigger and/or exacerbate the pathophysiological substrates of AD.10,11 Likewise of importance are interrelated and interacting processes of deficient autophagy, mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle re-entry (CCR) which can ultimately lead to neuronal loss (Figure 1).11-14

While aberrant generation of Aβ42 and plaque formation anticipates the formation of tau neurofibrils (Figure 1), these characteristic facets of AD are at least partially independent.5 Further, despite the current preoccupation with an Aβ42-tau axis of causation, other mechanisms are involved in the pathogenesis of AD, and the complex web of cerebral anomalies awaits further elucidation.3-5

Genetic and environmental risk factors for familial and sporadic AD

A minority of familial AD cases (about 5%) are provoked by dominant, autosomal mutations in the gene encoding the Aβ42 precursor, amyloid precursor protein (APP), and in the genes encoding Presenilin (PS) 1 and PS2, catalytic components of the γ-secretase complex that processes APP downstream of β-secretase (BACE-1).7,15 The effects of mutations are not limited to alterations in the quantity of Aβ42 engendered. Rather, reflecting loss of physiological function/gain of toxic function, multiple mechanisms are involved, such as altered processing of APP into Aβ42 vs related APP-derived species, as well as APP-independent mechanisms such as defective autophagy.6,15,16

As for late-onset, sporadic (non-Mendelian) AD, the apolipoprotein-E (APO-E) allele (4 deleterious vs 2 protective) is by far the greatest genetic risk factor, with more than 60% of patients being Apo-E4 carriers. Apo-E4-accrued risk is related to: (i) increased APP membrane insertion and processing; (ii) decreased glial and blood-brain barrier Aβ42 clearance; and (iii) promotion of Aβ42 aggregation, though Aβ42-independent mechanisms are also involved.17-19 Nonetheless, an Apo-E4 phenotype is not of itself sufficient to provoke the disorder and, despite some additional risk genes identified by unbiased genome-wide association studies, genetic factors alone cannot explain late-onset AD.19

It is then important not to neglect environmental risk factors like age and gender, cerebral trauma and stroke, hypertension and diabetes, chronic stress and depression. They are superimposed upon a genetic foundation of greater or lesser vulnerability and act via cellular mechanisms indicated above like oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation and apoptotic cell loss (Figure 1). 1,10-14

Collectively, multiple genetic and environmental risk factors lead to diverse molecular anomalies associated with AD, and by no means restricted to the prototypical signatures of excess Aβ42 and aberrant tau-PTM.

Epigenetic mechanisms and the pathophysiology of AD

From the above remarks, it may be posited that epigenetic mechanisms lying at the interface of genetic and environmental risk factors participate in their detrimental effects, and hence to the onset and progression of, AD.20-22 Some epigenetic shifts contributing to AD may arise well before diagnosis, even in early development.23,24 Conversely, certain epigenetic changes appear to be downstream of core AD pathophysiology and elicited in response to, for example, Aβ42 and oxidative stress21,25,26—see below. The following paragraphs exemplify this dual cause-and-effect relationship of epigenetic processes to AD, while also underlining their Janus-like impact in both restraining and, more prominently, encouraging disease progression.

For the purpose of this discussion, epigenetic refers to sustained and potentially heritable (by meiosis and/or mitosis) alterations in gene expression exerted in the absence of altered DNA sequence.27 With the possible exception of residual pockets of adult neurogenesis, the notion of “trans-generational,” postmitotic inheritance of DNA sequence-independent changes in gene activity by daughter cells is not of great relevance to AD. Rather, we are concerned with mechanisms that modify the sinuous route from gene to functional protein in the cell itself.

The broad suite of epigenetic mechanisms affected in AD ranges from DNA methylation to altered posttranslational marking of histones to regulatory actions of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), with a particularly rich (and challenging) literature devoted to microRNAs (miRNAs, or miRs).

DNA methylation and AD

DNA methylation is mainly effected at promoters and it exerts a repressive influence on gene transcription. It is dynamically regulated in mature neurones, as exemplified by the existence of both DNA methyltransferases and DNA demethylases, though the latter are less well-characterized.20,27-29 DNA methylation is dependent upon the folate-methionine-homocysteine cycle and, though data are not fully consistent, a deficit in folate (and/or an increase in homocysteine) levels has been related to aging and specifically to AD.21,22,30

Several studies have reported both widespread and promoter-specific alterations in DNA methylation in the hippocampus and cortex of AD patients compared with normally aged control subjects—to some extent resembling a profile of accelerated and “exacerbated” aging.21,22,31-33 DNA hypomethylation has been correlated with a greater amyloid plaque burden, enhanced APP production, and increased activity of enzymes (BACE-1/PS1) involved in the amyloidogenic processing of APP and generation of Aβ42.32-34 Those observations are underpinned by studies of cellular models and transgenic mice, with a possible role for oxidative stress in the induction of these changes.25,30,35-37 In addition, observations in the frontal cortex of AD subjects, supported by cellular work, reveal that DNA hypomethylation results in an upregulation of the proinflammatory gene, Nuclear Factor-kB (NF-kB), as well as that encoding cyclooxygenase-2 which catalyses the generation of prostaglandins and other prostanoids.38,39 This suggests that aberrant DNA methylation may drive neuroinflammation. Conversely, the hypermethylation of promoters for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c AMP-responsive element (CREB) would interfere with synaptic plasticity.38 Intriguingly, alterations in DNA methylation have been seen prior to the onset of symptoms, likewise consistent with a causal role.24 Thought it is not yet entirely clear how these changes in DNA methylation status are triggered, several cellular mechanisms implicated in the genesis of AD may be responsible, including oxidative stress—and Aβ42 itself, possibly as part of a positive feedback loop.25,30,37

Another open question is why and how alterations in DNA methylation occur in an at least partially promoter/gene-dependent manner. For example, a study in cerebral endothelial cells described a global pattern of hypomethylation, with a patch of hypermethylation at the promoter for the Aβ42-degrading enzyme, neprilysin, resulting in a reduction of Aβ42 clearance.40 Furthermore, Aβ42-induced alterations in DNA methylation have been specifically related to the discrete induction of genes eliciting apoptotic cell loss.41

Intriguingly, many classes of miRNA implicated in AD are controlled by promoter DNA methylation.42 Contrariwise, miR-148a, a microRNA increased in AD,43 diminishes translation of mRNA encoding DNA methytransferase—at least in non-neuronal cell lines.44 These observations suggest that the interplay amongst epigenetic mechanisms controlling protein expression will be disrupted in AD, and this likely extends to interactions between miRNAs and histone-PTM42,45 (see below).

To summarize, the above comments suggest that altered patterns of DNA methylation lie upstream of, and contribute to, many core pathophysiogical processes incriminated in AD. Reciprocally, however, Aβ42 itself and oxidative stress can modify DNA methylation. The functional relevance of aberrant DNA methylation to AD is supported by evidence for its dynamic modulation of learning and memory.27,29,46 Further clarification of the interplay between DNA methylation and AD pathophysiology would be of considerable interest.

Histone acetylation/methylation and AD

A second and widespread mechanism for epigenetic control of gene expression relates to the histone code. That is, alterations in methylation, acetylation and other post-translational modifications of histones,27,47 which change their conformation and hence the access of transcription factors and other chromatin regulators to specific zones of DNA. An “open” configuration favors transcription, whereas a closed configuration hinders it. Histone acetylation (acetyl transferase-mediated) and phosphorylation (kinase-imposed) generally favors transcription. Histone methylation (methyl transferase-mediated) is more complicated and site-dependent. For example, when enforced at H3Lysine 4, transcription is enhanced, whereas methylation at HSLysine 9 is inhibitory.2,27,47-49 Histone marks are deleted by phosphatases, specific demethylases, and histone deacetylases (HDAC) like HDAC2, blockade of which is associated with pro-cognitive properties.27,48-49 Indeed, HDAC2 inhibitors have been proposed as potential procognitive agents for the treatment of AD27,48-50 and histone methylation likewise exerts a marked influence on synaptic plasticity and cognition.27,49,51

Surprisingly, few data concerning histone marks are available from human tissue, yet there was a decrease in histone acetylation in temporal cortex,52 and a decrease in histone H3 acetylation has been reported from transgenic mouse models of AD.53,54 A possible explanation—supported by work in animal models of AD and cell lines—would be overactivity of HDAC2, blockade of which relieves cognitive impairment.48 Similarly, in transgenic mice, HDAC2 inhibitors: normalized spatial memory, augmented markers of synaptic plasticity and countered neuroinflammation and behavioral deficits.53,55 Dysregulation of histone H4 acetylation has also been linked to cognitive deficits in double transgenic APP-PS1 mice.54

While H3 hyperacetylation participates in the induction of APP, BACE1 and PS1 by cellular stress,37 in a reciprocal manner, Aβ42 itself may provoke anomalous patterns of histone acetylation.56 An interesting illustration is provided by a study where neuroinflammation intervened in the influence of Aβ42 on histones, with a suppression of H3 acetylation (coupled to promoter DNA hypermethylation) resulting in reduced expression of the post-synaptic regulator of synaptic plasticity, Neuroligin-1.57

Finally, oxidative stress downregulates neprilysin gene expression (and hence Aβ42 clearance) in cultured neuronal cells via increased H3Lysine9 methylation and reduced H3 acetylation.58

To summarize, there is evidence for a reciprocal interplay between anomalies in histone-PTM and other pathophysiological changes in AD. Currently, most data support a primary role for aberrant histone-PTM upstream of—and driving—pathology, including accelerated production of Aβ42 and a reduction in its clearance. At the cellular level, the question arises of what triggers the disruption of histone PTM: while there is evidence for a role of cellular stress, this is unlikely to be the only factor.25,37 There is a need for further exploration of alterations in histone-PTM in AD in comparison to normal aging, and distinguishing events in neuronal vs glial cells, since they may well differ.

Noncoding RNAs and AD: focus on miRNAs

Another dimension of epigenetic control, exerted mainly (but not only) at the level of translation, is afforded by a rich repertoire of short and long noncoding (lnc) RNAs that do not encode proteins: several are deregulated in AD. While some ncRNAs overlap with genes (exons and introns) encoding proteins, most are derived from the vast intergenic domain of DNA that structures and regulates the human genome: not exactly dark matter, but nonetheless very gray.59-62

NcRNAs are divided into short and long species which are, by convention, less and more than 200 nucleotides in length, respectively. Prominent amongst the former are miRNAs, for which a substantial but sometimes baffling (even for the initiated) body of evidence has accumulated in AD. Hence, to facilitate understanding of the roles of miRNAs in AD and their links to its molecular substrates, summary Tables accompany the discussion below.

More than 2000 classes of miRNA are currently-recognized in humans with the majority found in the brain and some enriched in cerebral tissue. They are produced by the successive actions of: RNA polymerase III which generates a long, precursor pre-miRNA; nuclear splicing of the pre-miRNA by “Drosha”; and export and further splicing of this shorter form in the cytosol by “Dicer.” The mature single strand of miRNA interacts via its 2-8 “seed” nucleotide, 5-Untranslated Region with a complementary region of its target mRNA in a so-called “RNA-induced silencing complex—RISC.” When matching is perfect, target mRNAs is degraded or, when matching is imperfect, mRNA translation into protein is hindered.

Each species of miRNA can recognize up to hundreds of different target mRNAs. Further, most target mRNAs are controlled by numerous species of miRNA. Redundancy and crosstalk are, then, fundamental features of miRNA neurobiology.27,59-61,63 Together with the sheer number of miRNAs, this renders understanding and discussion of the roles of miRNAs in AD exceptionally complex. The following sections (complemented by the Tables and Figures) describe, explain and integrate most of the major facets currently known, but many likely remain to be discovered, and a full synthesis is not yet possible.

Alterations in the cerebral expression of miRNAs in AD

Several studies have examined changes in miRNA levels in the brains of AD sufferers in comparison with normally aged subjects, as summarized in (Table I). 64-67 As discussed elsewhere,43,65,68 the use of contrasting procedures for measuring miRNA levels may account for some discrepant findings between studies: for example, as illustrated by miRs-9 and 128 (Table I). 43,69,70Another explanation is differences between brain regions. In this regard, it should be noted that anatomical resolution is still very limited, despite an intriguing study that found contrasting patterns of changes in white vs gray matter of the temporal cortex.67 This lack of resolution is worrying since there is no certainty that all classes of cell will behave similarly, nor even that miRNAs are homogeneously distributed amongst them: for example, neurones vs microglia, and pyramidal glutamatergic projection neurones vs γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ergic interneurones. This was recently shown for miR-132 in the frontal cortex71 and is well-established for other epigenetic mechanisms like DNA methylation and histone-PTM.27,29,49

Table I. (Opposite) Overview of changes in miRNA seen in cerebral tissue of Alzheimer's disease patients. In certain cases, a single species of miR was studied whereas other investigations quantified multiple species. Amongst the latter, those species of miRNA for which robust changes were seen are highlighted. In the interest of clarity, miRNAs which did not change are not shown. Ref 88 should be consulted for lists of the very large number of alterations in levels of miRNA documented across various studies. III/IV and V/IV refer to Braak stages, and correspond to mild/moderate vs late-stage AD, respectively. In certain investigations, the mRNA/protein targeted by the miRNA in question was directly quantified in tissue in parallel (indicated in italics). qRT-PCR signifies quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction. Overall direction of changes. Decreased (↓): miRs 15a;29a,b; 103; 106; 107; 124a; 132; 137; 146a; 146b; 153; 181c; 210; 212; 339-5p and 485-5p. Increased (↑): miRs 26b; 34a,c; 125b; 1 44; 146a; 155 and 206. No consistent pattern; Let-7 and miRs 9, 101 and 128a. However, for certain, only one observation is available, one cerebral structure, one time of measurement, one method of quantification and/or a small patient cohort etc so, for essentially all species, further data would be desirable to confirm the patterns of effect.

| Structure(s) analyzed | Technique | Major changes in discrete regions (Braak stage) Targeted mRNA/protein quantified in parallel | Reference |

| Frontal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiR-339-5p | 87 |

| ↑Beta-secretase1 | |||

| Hippocampus | qRT-PCR | ↑MiRs-34c (III/IV), 146a (III/IV) | 70 |

| ↓107, 128a (V/VI) | |||

| Prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, Temporal cortex | qRT-PCR, In situ hybridization | ↓MiRs-132, 212 (III/IV and V/VI) | 74 |

| ↑Forkhead transcription factor, FOXO1A | |||

| Substantia nigra | qRT-PCR | ↑MiRs-26b (III/VI), 29c (III), 125b (III). | 83 |

| Frontal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiR-153 (III, VI) | 84 |

| ↑Amyloid precursor protein in patients showing tangles | |||

| Hippocampus | qRT-PCR | ↑MiR-34c (V/VI) | 85 |

| Anterior temporal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiRs-107, 124 | 76 |

| Frontal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiRs-9,29a,29b,137,181c | 79 |

| ↑Serine palmitoyltransferase | |||

| Superior middle temporal cortex | Northern blot, Microarray | ↑Ca 80 MiRs spread across white and gray matter. | 67 |

| ↓Ca 100 MiRs spread across white and gray matter. | |||

| Cerebral cortex | qRT-PCR, Microarray | ↑MiRs-101,144 | 89 |

| ↓Ataxin 1 | |||

| Temporal cortex (gray matter) | qRT-PCR | ↓MiRs-107 | 77 |

| Superior temporal cortex, hippocampus | Northern blot, Microarray | ↑MiRs-146a | 72 |

| ↓Interleukin 1 receptor activating kinase 1 | |||

| Entorhinal cortex, hippocampus | qRT-PCR | ↓Mirs-485-5p | 122 |

| ↑Beta-secretase1 | |||

| Frontal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiRs-29a | 90 |

| ↑Neurone navigator 3 | |||

| Parietal cortex | Microarray | Many classes of miR correlated positively or negatively with target mRNAs. No precise information on changes. | 88 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | qRT-PCR | ↑MiRs-27a,b,30,34a,125b,145,422a | 43 |

| ↓MiRs-9,26a,27a,132,146b,210,212 | |||

| Hippocampus | ↑MiRs-26a,30a,124a,125b,145,422a | ||

| ↓MiRs-9,27a,132,146b,210,212 | |||

| Cerebellum | ↑MiRs-27a,b,34a,125b,145,422a | ||

| ↓MiRs-9,132,146b,210,212,425 | |||

| Changes seen at both III/IV and V/VI except 9,212 and 422 (IV/VI), and 27a, 34a (III/IV) | |||

| Anterior temporal cortex | qRT-PCR | ↓MiR-106b | 119 |

| Anterior temporal cortex | qRT-PCR, Microarray | ↓MiRs-9,15a,19b,26b,29a,101,106b,181c,210,Let-7 | 80 |

| ↑197,320,511 | |||

| ↑Beta-secretase1 (related to decreases in 29a,b) | |||

| Superior and middle temporal cortex | Northern blot, Microarray, In situ hybridization | ↓MiR-107 | 78 |

| ↑Beta-secretase1 | |||

| Superior temporal cortex, Hippocampus | Northern blot, Microarray | ↑MiR-146a | 86 |

| ↓Complement Factor H | |||

| Temporal cortex | Northern bolt, Microarray | ↑MiRs-9,125b,146a | 73 |

| Hippocampus | Northern blot | ↑MiRs-9,128a | 69 |

Nonetheless, there are some fairly consistent changes such as: (i), increases in miR-146a in temporal cortex and hippocampus72,73 and, in an opposite direction, decreases in miR-132 in several brain regions74,75; (ii), reductions of miR-107 in temporal cortex76-78; and (iii) diminished miR-181c in frontal cortex and temporal cortex.79,80 The latter change is interesting since it is mimicked by similar decreases in animal models for AD. Further, Aβ42 exerts comparable effects on miR-181c in a cellular procedure (see further below).79,81,82 Another interesting point comes from studies that have looked at the time-course of changes. Some emerge rather early (Braak III/IV) and are sustained, some appear early and subside, and some are apparent only at a later phase (Table I) 43,70,74,83-85 Early-onset changes are most compatible with the notion of causation. It is important to relate changes to target mRNAs. Most studies have done this using cell lines, yet a few have shown - more compellingly - that levels of target proteins and/or mRNAs are inversely correlated to levels of miRNAs in cerebral tissue.72,74,79,80,84,86-90

Amongst these observations, many alterations in miRNA levels would be expected to provoke or aggravate AD pathology, such as an increase in the activity of BACE1, the rate-limiting enzyme for generation of neurotoxic Aβ42 generation from its precursor, APP (see below). One intriguing exception appears to be miR-181c. Despite a facilitation of Aβ42 generation via disinhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase (see below),79,91 reduced levels of miR-181c would be associated with several favorable repercussions:

Activation of the deactylating enzyme, Sirtuin1 (downregulated in AD), which fulfils a broad prosurvival and procognitive role92,93

Reinforcement of the anti-apoptotic factors, Bcell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) and X-linked apoptotic factor, which will counter neuronal loss

Induction of microglial mechanisms of neuroprotection.81,82,94-96

To summarize, as shown in Table I, a broad suite of changes in the levels of numerous miRNAs has been seen across several brain regions in AD, both increases and decreases. Some changes are seen early in the disorder, consistent with a causal role in pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD. However, at least certain miRNA responses may be counter-regulatory and fulfil a protective role. These points are further elaborated on below.

Comparisons of miRNA changes in AD patients to transgenic models of AD

Complementary to studies of AD patients, changes in miRNA levels have been explored in transgenic mouse models for AD.97-99

While some miRNAs impacted in AD models are not known to be affected in patients, like miR-298 (which targets BACE1),100 there are interesting parallels to clinical studies. For example, mimicking studies in human AD,72,73,79 decreases in miR-181c levels were reported in a mutant APP transgenic mouse model of AD.81,82 Conversely, and likewise resembling AD, miR146a was upregulated in a variety of other transgenic AD mice lines.101 Interestingly, miR-34c was only increased in 24 but not 2-month-old double mutant (APP and tau) mice, resembling its elevation in late-phase AD.85 In another study of the time-course of changes, levels of miR-34a were upregulated prior to the accumulation of plaques in a transgenic model for AD in a similar manner to its precocious upregulation in human hippocampus.43 Furthermore, a key miRNA target, the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl2, was concurrently downregulated in this mouse model.99 This change in miR-34a levels was mirrored by increases in several further microRNAs, whereas others were decreased, indicating miRNA species-specificity of changes.99

It is worth noting that senescence-accelerated mice show a downregulation of miR-16, and normalization of its activity by over expression reversed APP overproduction and plaque proliferation.102 This study provides direct evidence for a causal role of this miR-16 in driving pathological changes, though it remains unknown whether miR-16 is impacted in AD patients. Many other classes of miRNA are likewise altered in senescent mice, and another one deserving mention is miR-20.103 MiR-20a inhibits several mechanisms driving AD, namely generation of Aβ42 and phosphorylation of tau. However, it also inhibits several substrates opposing progression of AD: namely, activity of the antiapoptotic factor, Bcl2, and of transdermal growth factor (TGF). These proteins protect against the loss of neurones and enhance the clearance of Aβ42, respectively.103,104 MiR-20a illustrates, then, the complex role of even a single species of miRNA.

To summarize, several (though not all) species of miRNA show alterations of levels in animal models resembling those seen in AD patients, both as regards the direction of changes and their time course. Further, these changes can be experimentally related to expression of the target mRNA and to the functional status of animals. Thus, further studies of miRNA in transgenic mouse models as compared with AD patients should prove instructive for clarifying their roles in driving and delimiting AD pathophysiology.

Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in AD that impact and interact with miRNAs

MiRNAs upstream and downstream of core pathophysiology

As pointed out above, some lines of evidence suggest that changes in miRNA levels may be a response to Aβ42 and additional risk factors for AD. Conversely, other findings indicate that miRNAs may be provoking cellular anomalies that favors the progression of AD.

These downstream vs upstream scenarios have been extensively examined in cellular models, as outlined in this and the following section.

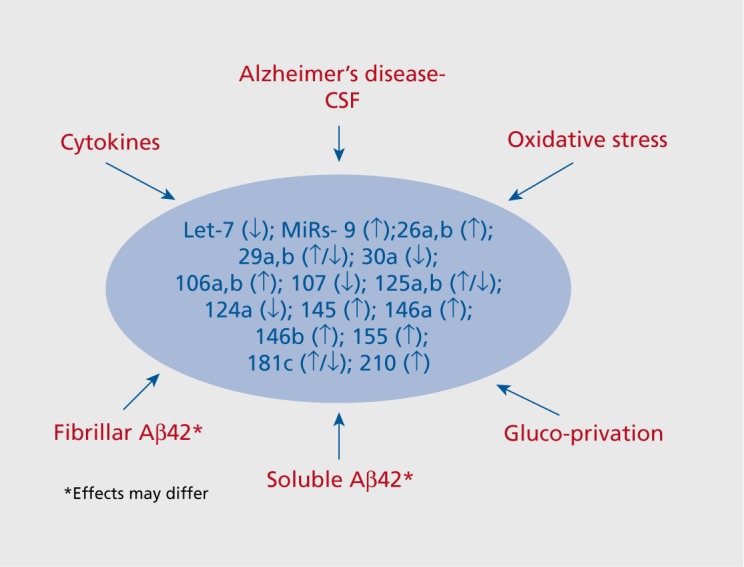

Exposure to Aβ42 and oxidative stress: impact on miRNAs

As mentioned above, miR-181c is decreased both in AD patients and in transgenic mouse models for AD. Accordingly, its downregulation in vitro by fibrillar Aβ42 is consistent with the notion that the decrease in miR-181c levels seen in AD may be downstream of Aβ42 Figure 2. 103,104 Several other classes of microRNA were also downregulated by Aβ42 including miR-9, though not all findings have found a decrease in this microRNA in AD (Table I). Complicating the situation, a recent study found that the effects of soluble forms of Aβ42 differ from those of fibrillar Aβ42 (Figure 2).6 In the latter study, some microRNAs were upregulated by soluble Aβ42 in a N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent fashion. This is consistent with a role for NMDA receptors in mediating Aβ42 neurotoxicity, perhaps since these receptors are hijacked by Aβ42 in order to enter neurones where it affects miRNAs.106 Conversely, other classes of miRNA were downregulated by soluble Aβ42, including miR-107 which is decreased in AD brain (Table I). This effect of soluble Aβ42 on miR-107 was mimicked by peroxide, indicative of a role for oxidative stress. This is interesting since oxidative stress is a well-known trigger for AD which elicits alterations in the expression of a variety of miRNAs in cellular paradigms (Figure 2).107,108

Figure 2. Overview of the regulation of multiple species of miRNA by cellular risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. In in vitro studies, a large number of miRs are modulated by exposure to β-amyloid42 (Aβ42) and cellular stressors implicated in the pathophysiology of AD. The direction and magnitude of change will depend upon the stimulus. Note that not all of these miRs have been evaluated in response to each type of stressor, and that many classes of miR remain to be examined.

To summarize, the above observations suggest that Aβ42 and oxidative stress provoke alterations in the expression of several classes of miRNA. Accordingly, a deregulation of miRNAs may contribute to their deleterious actions.

Exposure to neuroinflammatory signals: reciprocal interactions with miRNAs

Neuroinflammation has been identified as a potential source of neuronal damage antecedent to AD.10 Inflammatory mediators like Interleukin-1β enhance the expression of miR-146a, which is known to be upregulated in AD: this upregulation involves the prototypical, cytokine-responsive transcription factor, Nuclear Factor-kB (NF-kB) (Figure 2).86,109,110 It has been proposed that miR-146a acts as a molecular brake on other inflammatory cascades in a negative feedback manner, for example by suppression of the proinflammatory interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase.72,109,111 However, the situation appears to be more complex. For example, together with miRs-25 and 155 (which are likewise induced by inflammatory signals), miR-146 detrimentally suppresses the activity of Complement Factor H which itself inhibits inflammatory processes.109,112 This action would aggravate neuroinflammation.

In addition, downregulation of miR-101 in AD80 would disinhibit cyclooxygenase 2, hence contributing to excessive production of prostaglandins.11,37 Furthermore, the induction of miR-125b by inflammation would inhibit 15-lipooxygenase—which protects against toxic actions of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species—hence worsening oxidative stress.73,109,113 On the other hand, reduced levels of miR-107 in AD would disinhibit the anti-inflammatory peptide, progranulin.114,115

Underscoring the complex interplay between microRNA and inflammation, miRs-146a and -155 can be released from neurones to induce inflammatory processes by, for example, interference with complement factor H in other cells.116 In addition, Let-7b is liberated into the extracellular space where it activates Toll-7 receptors on glia and neurones resulting in a NF-kB-driven cascade that leads to apoptosis.117 Though variable changes have been seen for Let-7 family members in AD brain tissue (Table I), Let-7 levels are elevated in the CSF, consistent with cell-to-cell transmission of this deleterious, proinflammatory miRNA.117

To summarize, several classes of microRNA are induced by neuroinflammatory mediators, while others reciprocally regulate inflammatory signaling. As regards the latter process, certain classes of miRNA reinforce and transduce neuroinflammatory processes driving the genesis of AD, whereas others act in an opposite, protective fashion. These observations underline the Janus-like facet of microRNAs, a take-home message underscored throughout this review.

Molecular mechanisms resulting in altered levels of miRNAs

The question arises as to which mechanisms of miRNA regulation account for changes in their levels in AD patients, mouse models, and cellular paradigms. Oddly enough, very little is known but altered transcription, processing and degradation have all been proposed as explanations: interactions with other classes of ncRNA may also be implicated.59,60,62,73,81,82,109

Impact of miRNAs on pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in AD

Modulation of the generation of Aβ42

MicroRNAs exert a broad suite of actions to modify the amyloidogenic processing of APP into neurotoxic Aβ42 which is effected by consecutive actions of the cleaving enzymes, BACE1 , followed by y-secretase (Figure 1, Table II). MiRNAs also affect an alternative, non-amyloidogenic (non-toxic) pathway of APP processing which yields soluble APPα via the actions of AD-related disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM-10).15-16 Several key interactions are highlighted below.

Multiple species of microRNAs, including miRs-106 and 153, target mRNA encoding APP so their downregulation in AD (Table I) would lead to enhanced production of Aβ4284,118-120

Loss of miR-124a would promote the activity of polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTBP) and hence lead to altered splicing of pre-mRNA encoding for APP: more specifically, to generation of AD-associated isoforms containing exons 7 and 876

miRs-137 and 181c both target serine palmitolyltransferase, the rate-limiting enzyme for synthesis of ceramides which favor lipid raft insertion, endocytosis and processing of APP. Again, downregulation would promote APP processing into Aβ4279

Numerous microRNAs reduced in AD converge onto BACE1, including 27a-3p, 29a, 107, 124a, 339-5p and 485-5p: their downregulation will favour the amyloidogenic pathway of Aβ42 production.78,80,87,121-124 Furthermore, upregulation of miR-144 would suppress the activity of Ataxin1 and hence relieve its inhibitory control of BACE1, to further encourage Aβ42 generation.89,125

The above observations comprise a remarkably consistent set of actions suggesting a causal role of miRNAs in accelerating the generation of neurotoxic Aβ42 in AD. As for the alternative pathway, reduced levels of 107 (and 103) would simultaneously disinhibit the activity of ADAMIO and non-amyloidogenic products of APR126 More insidiously, however, the activity of ADAMIO would be suppressed by upregulation of miR-144 which is recruited by Activator Protein 1 itself induced by Aβ42.127 Further, both miR-125b and 146a upregulation will suppress Tetraspanin 12, a protein that facilitates activity of ADAMIO.128,129

To summarize, a broad and coherent palette of observations suggests that microRNA deregulation in AD is associated with the accrued BACE1-effected processing of APP into Aβ42. These observations support a role for miRNAs in driving pathophysiological processes underlying AD. Further, this role of miRNAs may be expressed early in the disorder inasmuch as accumulation of Aβ42 begins well before clinical diagnosis.6,7

Influence upon anomalous post-translational processing of tau

Excess formation of Aβ42 contributes to the induction of aberrant post-transcriptional modifications of tau, though other upstream mechanisms are also involved.5,8 Anomalous patterns of tau-PTM, mainly hyperphosphorylation and acetylation, favour tau disassociation from microtubules. This leads to microtubule destabilization and the disruption of axonal-neuritic stability and transport, as well as to “gain of toxic function” of tau in other subcellular compartments, like the synapse.9,130 Many mechanisms impacting tau-PTM and axonal integrity are under the control of microRNAs affected in AD (Table II). Some examples are given below.

Table II. Overview of the influence of diverse species of miRNA upon generation, processing and elimination of Aβ42 and Tau, processes disrupted in Alzheimer's disease. The Table is nonexhaustive and limited to miRNAs known to be deregulated in AD - see text for details. Cdk5, cyclindependent kinase 5; IGF, insulin growth factor and BAG, Bd2-regulated anthogene. For other abbreviations, see list at beginning of paper.

| Process | MiRNA target | Species of MiRNA |

| Synthesis of amyloid precursor protein (APP) | APP | 16, 17-5p, 20a, 101, 106a/b, 153 |

| Alternative splicing of APP | PTB1/2 | 124, 132 |

| Lipid raft localization and endocytosis of APP | Serine palmitoyl transferase | 137, 181c |

| Cleavage of APP into Aβ42 | β-secretase 1 | 9, 29a/b, 29c, 107, 124, 195, 298, 328, 339-5p |

| Inhibition of BACE1 activity | Ataxin 1 | 144 |

| Cleavage of APP into soluble APP | ADAM10 | 107, 144 |

| Facilitation of ADAM10 | Tetraspanin12 | 125b, 146a |

| Synthesis of tau precursor protein | Tau | 27a-3P, 34a |

| Hyperphosphorylation of tau | Extracellular regulated kinase 1 | 15a, |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | 103, 107 | |

| Glycogen synthase kinase-3β | 26b, 27a-3p | |

| Acetylation of tau | P300 (on) | 132, 212 |

| Sirtuin11 (off) | 9, 34a/c, 132, 181c, 212 | |

| Microglial clearance of Aβ42 | TBFβII receptor | 181c |

| Lysosomal clearance of Aβ | IGF receptor | 29a |

| Transcription factor Eβ | 128a | |

| Autophagic clearance of Ab42 and tau | Beclin (induces autophag), | 30a |

| Cdk5 (inhibits beclin) | 103, 107 | |

| Proteosomal elimination of tau | BAG2 | 128a |

First, the synthesis of tau itself would be accelerated by reductions in the levels of miR-27a-3p and 34a, both of which target it directly.124,131 Second, the tau precursor can be alternatively spliced by the abovementioned APP-processing enzyme, PTPB. Its actions will modify the ratio of “4R” to slightly-shorter “3R” isoforms, the former being more prominent in AD. Thus, downregulation in AD of miR-124a and 132, which target PTPB, will favour aberrant splicing of tau into neurotoxic isoforms.9,75 Third, downregulation of miR-15a, 103/107 and 27a-3p enhances excess phosphorylation of tau by extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)1, cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)-5 and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-P respectively.132,133 On the other hand, an increase in miR-26b would act oppositely to repress GSK3β.83

As for acetylation, in contrast to the vast panoply of sites susceptible to phosphorylation (over 80),8 onlyone site for acetylation (Lysine-280) has been well-characterized, with a role for addition of acetyl groups by p300 and their removal by deactylating enzymes like Sirtuin11. Curiously, both p300 and Sirtuin11 appear to be controlled by miR-132. On the other hand, while loss of miR-181c in AD would selectively upregulate Sirtuin1, increases in the levels of miR-34a,c would unfavorably restrict its activity.81,85,134-136

To summarize, then, the influence of alterations of miRNA levels in AD on tau phosphorylation and acetylation appears to be complex and bidirectional. While the balance of evidence suggests a deleterious impact, the data are not as consistent as those acquired for Aβ42, for which a collective enhancement in its formation can be deduced (see above). The question of whether aberrant tau-PTM reciprocally affects miRNAs has not as yet been addressed.

Influence upon axonal structure and function

A few studies have looked at other proteins that control axonal/neuritic stability and function (Table III). An interesting example is provided by studies of miR-29a: its downregulation in AD disinhibits Neurone Navigator 3. This poorly characterized protein controls axonal elongation and is found in neurofibrillary tangles, though its significance to AD is not entirely clear.90 In addition, deregulation of miR-9 in AD would impact two structural proteins, (i), microtubule associated protein-IB and (ii), neurofilament heavy, with downstream effects on axonal stability and neuritic plasticity.137,138

Table III. Influence of diverse species of miRNA upon axonal integrity and synaptic function, processes disrupted in AD. The Table is nonexhaustive and limited to miRNAs known to be deregulated in Alzheimer's disease—see text for details. MAP, Microtubule-associated protein; SNAP, synapse associated protein; SVG, synapse vesicle glycoprotein; Arc, activity-regulated cytoskeleta! protein; PSD, post-synaptic density protein; Limk, lim-domain-related kinase. For other abbreviations, see list at beginning of paper.

| Process | MiRNA target | Species of MiRNA |

| Axonal elongation | Neurone navigator 3 | 29a |

| Axonal and neuritic stability plasticity | MAP1β | 9 |

| Neurofilament heavy | 9 | |

| Vesicular release of transmitters from presynaptic terminals | Synapsin2 | 125b |

| SNAP-25 | 153 | |

| SVG2A | 485-5p | |

| Postsynaptic signaling and organization | NMDA receptor subunit NR1 | 15b |

| Arc | 34a,c | |

| PSD-95 | 125b | |

| Structural and functional synaptic plasticity dendritogenesis | BDNF | 206 |

| CREB | 124,134 | |

| LimK | 134 | |

| Cofilin | 103,107 |

To summarize, the detrimental consequences of ADrelated microRNA dysfunction for axons and neurites are likely to be mediated by many classes of protein in addition to tau, yet they remain poorly-understood and warrant further investigation.

Influence upon synaptic function

One of the most prototypical features of AD is aberrant patterns of synaptic transmission, reflecting both structural and functional disruption, and a striking loss of plasticity. MiRNA changes in AD will negatively influence synaptic function both via deregulation of the axonal proteins mentioned above and by exacerbating anomalous marking of tau which, following separation from microtubules, becomes mis-localised in synapses. In addition, altered expression of miRNAs in AD will affect numerous pre and post-synaptic mechanisms controlling synaptic transmission (Table III).

At the presynaptic level, altered levels of miRNAs will interfere with the operation of several key proteins controlling vesicular release of neurotransmitters (miRNA/protein target): miR-125b/Synapsin 2; miR153/synapse associated protein-25 and miR-485-5p/synapse vesicle glycoprotein 2A.129,139-141

At the postsynaptic level, a plethora of proteins involved in transmitter-mediated signaling, synaptic plasticity, learning and memory are affected by deregulated miRNAs. These include (miRNA/protein target): miR-15b/NMDA receptors: miR-34a/activity-regulated cytoskeletal protein and miR-125b/Postsynaptic-Density 95. 142-144 Though details of the complex web of reciprocal interactions lie beyond the compass of this article, many other miRNA-regulated substrates of synaptic plasticity and cognition, notably CREB and BDNF, are perturbed in AD.145-149 In addition, it is worth evoking two less familiar proteins that directly control structural plasticity and dendritic spine growth: “lim-domain-related kinase” and its partner, the actin-interacting protein, cofilin. Their interrelationship is known to be modulated by several classes of microRNA deregulated in AD.148,150-153

This disruption of the interplay between microRNAs and proteins controlling neuroplasticity is hard to directly link to cognitive deficits of AD, but a couple of interesting examples can be cited. First, miR-206 is elevated in the temporal cortex both of AD subjects and of transgenic mice models for AD. It targets BDNF, so the increase of in miR-206 in AD will compromise cellular substrates underpinning cognition.154-155 An antagomir against miR-206 rescued BDNF protein translation and improved the cognitive performance of transgenic AD mice, providing still rare proof of a causal contribution of microRNA deregulation to the deficits of AD. Second, AD is associated with cellular stress which leads to the association of cofilin not only with actin but also with Aβ42 and tau-PTM to form rod-like structures. They disrupt mitochondria and may even provoke apoptosis.150 Accordingly, depletion of miRs-103 and 107 in AD, by disinhibiting cofilin synthesis, will leads to structural disruption of synapses and the perturbation of cognition: this possibility is supported by studies in transgenic mice models for AD.153

To summarize, deregulation of miRNAs in AD is a contributory factor to synaptic dysfunction. This reflects the disrupted activity of several key pre and post-synaptic proteins regulating synaptic organisation, neurotransmitter release and signalling. Recent studies have begun to link these aberrant cellular processes to the impairment of synaptic plasticity and cognition.

Influence on mitochondrial function and apoptotic cell loss

Mitrochondrial function is a crucial issue for: (i) AD, since insufficient energy supplies; and (ii) programs of mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis are incriminated in neuronal dysfunction, atrophy and ultimately neuronal loss, even early in the disorder.11 Not surprisingly, there are several ways in which miRNA deregulation in AD can impact mitochondrial function and integrity.

As mentioned above, destructive intrusion of cofilin into mitochondria may occur following release from miR103/107 suppression. Another manner in which deregulated microRNAs compromise mitochondrial integrity is via inhibition of Supraoxidase Dismutase 2 (which clears dangerous free radicals) following upregulation of miR146a.156 However, this may be counterbalanced by downregulation of miR-210 which would disinhibit iron sulphur assembly protein and accordingly promote mitochondrial efficacy and energy production.157-158 Again, while it is likely that miRNA disruption is predominantly deleterious, certain changes do appear to be beneficial.

As regards cell survival, miRNAs exert a broadbased influence on processes both favoring and restraining mitochondrial processes of cell elimination (Table IV). The potential inducer of apoptosis, “p53,” lies directly upstream of the Forkhead transcription factors (FOX)O1A and FOXG3A.159 These initiators of apoptosis act via recruitment of “Bax,” “Bim,” and “Bak” which trigger release of proapoptotic signals from mitochondria. P53 is held in check by the deactylating enzyme, Sirtuin1, which also restrains activation of FOXOIA and FOX03A by Aβ42.159 Sirtuin1 is under the inhibitory influence of both miR-181c and 34a,c, respectively down- and upregulated in AD (see above). Further, Sirtuin1 is also controlled by miR-132a, levels of which are reduced in AD.74,160 Hence, the balance of evidence suggests that changes in miRNA deregulation would favorably increase the protective activity of Sirtuin1. Unfortunately, however, loss of miR-132a74,160 will also disinhibit FOX01A/3A which activates “Bax,” “Bim,” and “Bak” to promote liberation of pro-apoptotic messengers from mitochondria. Moreover, the pro-apoptotic actions of Bim and Bak will be strengthened in AD by downregulation of miR 29a.161-162

Table IV. Influence of diverse species of miRNA upon mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle reentry, processes disrupted in Alzheimer's disease (AD). The Table is non-exhaustive and limited to miRNAs known to be deregulated in AD—see text for details. “Bim” and “Bak” are acronyms of proteins downstream of FOX01 A/3A that induce release of pro-apoptotic factors from mitochondria. XIAF, X-associated inhibitor of apoptosis; Rb, Retinoblastoma protein. For other abbreviations, see list at beginning of paper.

| Process | MiRNA target | Species of MiRNA |

| Induction of mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis | FOX1A/3A | 132a, 212 |

| Bim, Bak | 29a,b | |

| Inhibition of mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis | Sirtuin1 1 | 34a,c, 132a, 181c |

| Bcl2 | 15a, 29b, 153, 181c, 210 | |

| XIAF | 34a, 181c | |

| Induction of cell cycle re-entry | E2F1 transcription factor | 34a, 106a,b |

| Induction of cell cycle re-entry | Retinoblastoma protein | 26a,b, 106a,b, 124 |

| Cdk5 (non-catalytic inhibition of E2F1) | 26a,b, 103, 107 | |

| TGF signaling (p21 cyclin-mediated activation of Rb) | 106a,b, 181c |

A rather more consistent pattern of data has been reported for miRNA control of the inhibitor of apoptosis, Bcl2. This protein is under the influence of several miRs downregulated in AD like the abovementioned miR-181c as well as miRs-15a, 29b, 153, and 21098,104,105,164,165 However, in AD brain, cell lines and transgenic mice models of AD, overexpression of miR-34a suppresses Bcl2 and accelerates cell loss.99 By analogy, loss of miRs-34a and 181c in AD will oppositely influence X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis.163-164

To summarize, evidence that microRNA deregulation can impact mitochondrial mechanisms controlling energy production and, in particular, apoptosis is strong. Nevertheless, despite a tendency for the overall impact of miRNA disruption in AD to be deleterious, there is no unitary pro or antiaptoptotic impact. Rather miRNA-dependent actions are seen, and their collective pathophysiological significance awaits further clarification.

Influence on cell cycle re-entry and cell loss

Aberrant entry of post-mitotic neurones into the cell cycle, which cannot be completed owing to a lack of crucial regulatory proteins, results in their demise. In view of the dangers of CCR for mature neurones, it is prevented by a network of cellular brakes. Foremost amongst these is the so-called retinoblastoma protein (Rb).14 When not phosphorylated, Rb blocks the induction of CCR by binding to and inactivating the CCR inducer, “E2F1.” This E2F1 transcription factor is also restrained by physical association with (noncatalytic) Cdk5. Rb is phosphorylated by Cdk 4 and Cdk2 which interfere with its suppression of EF21 and hence activate the CCR. Normally, under healthy conditions, Cdk 4 and Cdk2 are themselves inhibited by the CCR-suppressor Cyclin p21. Failure of these molecular controls in AD (characterised by hyper-phosphorylated Rb) can be trigged by Aβ42 and anomalous forms of tau. This leads in turn to unsuccessful launching of CCR and cell death.114,165-167

Not surprisingly, the above -summarized molecular switches are subject to surveillance by several classes of microRNA, many of which are impacted in AD. It is difficult to be sure of the overall repercussions of miRNA deregulation, since certain changes will increase the risk of CCR, whereas others may be protective: in addition, certain species of miRNA have multiple roles (Table IV).They may be summarized as follows. First, upregulation of miR-26a,b would repress Rb and disinhibit E2F1, whereas decreases in miRs-106 and 124 would act oppositely.63,80,168 Second, again in an opposite manner, up and downregulation of miRs-34a and 106 would respectively increase and suppress levels of E2F1.66,168-169 Third, mirroring these contrasting patterns of influence, Cdk5 is oppositely regulated by miRs-26a, b and 103/107.83-133 There is one final level of upstream control worth mentioning since it would more consistently be affected in AD. That is, the role of TGF/TGFβII receptor-Smad signaling to stimulate p21 activity and hence maintain cell integrity by suppressing CCR. This control may be reinforced in AD by downregulation of both miR-106 and 181 which target TGFbeta II receptors.81,104,170-171

To summarize, reflecting the failure of cellular brakes, AD is characterized by the anomalous initiation of CCR which leads to the loss of neurones. Under normal circumstances, a diversity of miRNAs contribute to the suppression of CCR, so their deregulation in AD may be a contributory factor in its induction. However, several observations support the notion that miRNA changes in AD may actually counter the induction of CCR. It will be important to further decipher the role of miRNAs in the control of CCR in AD in view of the dire consequences of its disinhibition.

Influence on clearance of Aβ42 and aberrant forms of tau

Not surprisingly, mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis and CCR are interactive processes, and they both interface with mechanisms dedicated to the clearance of Aβ42 and tau which, as pointed out above, trigger neuronal cell loss in AD. The elimination of these neurotoxic proteins by a variety of neuronal and microglial mechanisms (Figure 1) is also regulated by epigenetic mechanisms.12,13,172,173

MiR-181c was evoked on several occasions above as regards beneficial consequences of its downregulation in AD. In addition, its downregulation would disinhibit the induction of microglial clearance of Aβ42 by TGF-βII. The downregulation of miR-106 in AD would similarly lead to higher levels of TGF-piI and accelerated off-loading of Aβ42.84-104,171 Complementing these positive effects, the downregulation of miR-29a would favor insulin growth factor driven clearance of Aβ42 by microglia.174

As regards the autophagic (neuronal) clearance of Aβ42 and tau, this is promoted by the protein Beclin, itself inhibited by Cdk5. As pointed out above, Cdk5 is targeted by miRs-103 and 107: their downregulation in AD would, then, be unfavorable in indirectly retarding autophagic processes.133,175 Similarly deleterious would be the upregulation of miR-30a in AD since it directly targets Beclin.175 The deregulation of miR-128a may similarly compromise the clearance of neurotoxic proteins in AD. Thus, upregulation of miR-128a in monocytes from AD patients was associated with reduced Aβ42 clearance,176 Further, miR-128a inhibits Bcl-2-related anthogene protein which coordinates the proteosomal degradation of insoluble forms of hyperphosphoryated tau. Interference with this mechanism would compromise the efficiency of tau clearance.177

To summarize, the deregulation of several species of miRNA will modify the clearance of neurotoxic proteins in AD. Intriguingly, it would appear that microglial elimination is enhanced, whereas neuronal autophagic and lysosomal/proteosomal disposal is compromised. This dichotomy warrants additional study in view of the marked therapeutic importance of ridding the brain of neurotoxic proteins.

Other classes of small ncRNA and long noncoding RNAs

Though the vast majority of studies have focussed on miRNAs, they are not the only class of small ncRNA relevant to AD. The neurobiology of other classes of ncRNA is poorly developed as regards AD, but the following observations suggest that they justify greater interest.

First, levels of the small ncRNA “17A” are elevated in AD, and it is induced by inflammation in vitro. In addition to its modulation of transmission at GABAB receptors, which harbor the stretch of DNA encoding 17A, this short ncRNA provokes the secretion of Aβ42, suggesting a detrimental impact in AD.178 Second, the circular RNA, ciRS7, is colocalized in hippocampus and cortex with miR-7 and interferes with its actions. CiRS7 is downregulated in AD brain resulting in over-activity of miR-7 and, in turn, downregulation its target Ubiquitin-like Ligase which is involved in Aβ42 clearance.179 Third, certain classes of so-called “piwi” RNAs interact with miR-124/132 and CREB in the control of synaptic plasticity and dendritogenesis in hippocampus, and their deregulation in AD is suspected to perturb synaptic transmission, though this remains to be formally proven.27,180 Finally, the small ncRNA “BC200” controls synaptic plasticity via actions in dendrites and, in contrast to normal aging, its levels increase in AD in parallel with a mislocalization in the soma.181 Collectively, then, these limited observations suggest that the deregulation of a variety of short ncRNAs other than miRNAs may participate in the pathophysiology of AD.

At the other end of the spectrum to small ncRNAs, their long counterparts (IncRNAs) include an estimated 10 000 or so sequences. Some of them are processed into miRNAs, some compete with miRNAs for access to mRNAs, some mop up miRNAs, and some bind to DNA and proteins.27,59,62 This suggests a vast panoply of relevant actions still awaiting discovery. Though little is known about their presumptive deregulation and roles in AD, they are likely to go haywire. One neat example of their “promise” is provided by a IncRNA which acts as an antisense to miR 485-5p that itself neutralizes mRNA encoding BACE1. Upregulation of this IncRNA antisense in AD and mouse models for AD reduces the activity of miR-485-5p and hence indirectly increases levels of BACE1. This will in turn accelerate APP processing into Aβ42.122 Interestingly, in something of a vicious circle, levels of lnc-RNA antisense to miR-485-5p are increased by Aβ42 and oxidative stress. These risk factors also modulate levels of IncRNA antisense sequences directed against ApoE and a DNA damage-repair enzyme, Rad18, suggesting a broader role of IncRNAs in the pathophysiology of AD that awaits further characterization.59,182

To summarize, in addition to miRNAs, several other classes of small ncRNA as well as IncRNAs are implicated in AD, and they are located both up and downstream of pathophysiological processes. Further, though it would be premature to make any generalized conclusions, there is evidence that their deregulation contributes to progression of the disorder. Thus, they are likely to be of importance, but a more precise understanding of their significance will necessitate considerable further study.

General discussion

Perhaps the most striking feature of the epigenetic dimension (or, more precisely, dimensions) of AD is the immense complexity—even for those familiar with this domain, the labyrinth of data can be quite intimidating. A related and no less important facet is the highly pervasive nature of epigenetic deregulation in AD, as regards its impact on essentially all core pathophysiological processes. It remains difficult to derive any definitive and/or generalized conclusions, but the following keypoints emerge from the discussion and justify emphasis.

First, there are numerous, compelling examples of epigenetic mechanisms that drive the progression of AD, notably as regards species of miRNAs affected early in the disorder and upstream of precocious pathological changes like Aβ42 accumulation. This is exemplified by the convergence of several classes of downregulated miRNA onto APP and BACE1. Accordingly, excess production of Aβ42 in AD can at least partially be attributed to anomalous epigenetic regulation by miRNAs - as well as aberrant patterns of DNA methylation and histone H3 acetylation. This is arguably the most broad-based and consistent consequence of miRNA deregulation in AD. Second, and conversely, certain epigenetic mechanisms oppose the evolution of AD. Selecting one miRNA as an example, the downregulation of miR-181c is accompanied by a distinctive palette of effects that counter-regulate the progression of AD. Nonetheless, even for miR-181c, its actions are not fully unitary. Third, the latter point highlights the notion of divergence whereby a single epigenetic mechanism, like a distinct species of miRNA, DNA methylation or histone acetylation can exert a broad and disparate suite of actions to either hinder and/or accelerate the progression of AD. Fourth, and reciprocally, certain epigenetic mechanisms are themselves affected by mechanisms causing AD, like Aβ42, cellular stress and neuroinflammation. Fourth, there are several cases of vicious circles/positive feedback loops whereby an epigenetic mechanism both drives and is driven by pathology. Though this raises something of a chicken and egg problem, the major implication of epigenetic anomalies in AD nevertheless appears to be upstream of pathophysiology.

Amongst the innumerable issues awaiting further clarification, the precise cellular localization of epigenetic changes is of importance to clarify. It is unlikely that all are homogeneously expressed throughout, say: all different cell types of the hippocampus, in neuronal and glial cells equally, or in glutamatergic GABAergic and monoaminergic neurones. It is also important to consider the subcellular compartmentalization of epigenetic regulation by ncRNAs since postsynaptic regulation in dendrites may differ from that seen presynaptic regulation in axonal terminals.

Concluding comments

In conclusion, to address the question formulated in the title of this article, certain changes in epigenetic mechanisms may be merely coincidental or correlated, some of limited functional impact, and others may be masked by high levels of redundancy. It cannot be excluded, moreover, that certain changes are “aspecific”: for example, secondary to apoptotic neurone loss. Nonetheless, from the above discussion, and despite many gaps in our current knowledge, it would foolhardy to dismiss the epigenetic dimension of AD as a “curiosity.” Certain epigenetic changes may be a “consequence” of pathophysiological processes underpinning AD, such as exposure to Aβ42, and certain may be triggered in parallel by common risk factors like neuroinflammation. However, the balance of evidence favours an upstream role of epigenetic processes, either opposing disease progression or, more commonly, favoring it, most conspicuously by increasing the generation of Aβ42. It is too soon to know whether deregulation of epigenetic controls is necessary and/or sufficient to trigger AD. Further, whether the term “causal”—rather than driving or aggravating—is appropriate remains to be clarified, since comparatively few animal and cellular studies have shown that interference with an aberrant epigenetic mechanism reverses pathophysiology and restores functional performance. Needless to say, such observations are entirely absent from patients. It might be contended, however, that this is no less true for many other mechanisms ostensibly incriminated in AD, even as concerns the significance of Aβ42 and tau-PTM.

The ultimate goal is to verify the therapeutic efficacy of epigenetic interventions for symptomatic and/ or course-altering management of AD. Though such studies still seem rather distant, considerable efforts are being made to: (i), amplify our understanding of the relevance of epigenetic controls and their regulation to the pathophysiology of AD vs normal aging; (ii) identify CSF and peripheral biomarkers reflecting epigenetic events in the brain43,70,183,184; and (iii), develop therapeutic strategies for manipulating epigenetic mechanisms - conventional small molecules, as well as mimics and blockers of ncRNA.2,27,29,49,185

The epigenetic dimension of AD is indubitably a crucial issue. Over the next few years, its significance for pathology should become clearer, providing a framework for the characterization of more reliable biomarkers and, in due course, the discovery and clinical evaluation of novel medication acting either directly or indirectly via epigenetic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Marianne Soubeyran for excellent secretarial assistance and San-Michel Rivet for expert manipulation of graphics. Two anonymous reviewers are thanked for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

- Aβ42

β-amyloid42

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADAM

AD-related disintegrin and metalloprotease

- APO-E

apolipoprotein-E

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BACE

β-secretase

- Bcl

B-cell lymphoma2

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CCR

cell cycle re-entry

- Cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CREB

cAMP-responsive binding element

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- FOX

Forkhead

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- miRNA

miR, microRNA

- ncRNA

noncoding RNA

- NF-kB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate

- PS

presenilin

- PTBP

polypyrimidine tract binding protein

- PTM

post-translational modification

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- TGF

transdermal growth factor

REFERENCES

- 1.Reitz C., Brayne C., Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:137. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adwan L., Zawia NH. Epigenetics: a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand R., Gill KD., Mahdi AA. Therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:27–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs HI., Radua J., Lückmann HC., Sack AT. Meta-analysis of functional network alterations in Alzheimer's disease: toward a network biomarker. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:753–765. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR., Knopman DS., Jagust WJ., et al Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benilova I., Karran E., De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer's disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karran E., Mercken M., De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer's disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:698–712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin L., Latypova X., Terro F. Post-translational modifications of tau protein: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spillantini MG., Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandelwal PJ., Herman AM., Moussa CE. Inflammation in the early stages of neurodegenerative pathology. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;238:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swerdlow RH., Burns JM., Khan SM. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: Progress and perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghavami S., Shojaei S., Yeganeh B., et al Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;112:24–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhopadhyay S., Panda PK., Sinha N., Das DN., Bhutia SK. Autophagy and apoptosis: where do they meet?. Apoptosis. 2014;19:555–566. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-0967-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swiss VA., Casaccia P. Cell-context specific role of the E2F/Rb pathway in development and disease. Glia. 2010;58:377–390. doi: 10.1002/glia.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haass C., Kaether C., Thinakaran G., Sisodia S. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006270. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chavez-Gutierrez L., Bammens L., Benilova I., et al The mechanism of γ-secretase dysfunction in familial Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:2261–2268. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Y. Abeta-independent roles of apolipoprotein E4 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends. Mol Med. 2010;16:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanekiyo T., Xu H., Bu G. ApoE and Aβ in Alzheimer's disease: accidental encounters or partners?. Neuron. 2014;81:740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert JC., Amouyel P. Genetics of Alzheimer's disease: new evidence for an old hypothesis?. Genet Dev. 2011;21:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu H., Liu X., Deng Y., Qing H. DNA methylation, a hand behind neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mastroeni D., Grover A., Delvaux E., Whiteside C., Coleman PD., Rogers J. Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1161–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J., Yu JT., Tan MS., Jiang T., Tan L. Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease: Implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:1024–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bihaqi SW., Schumacher A., Maloney B., Lahiri DK., Zawia NH. Do epigenetic pathways initiate late onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD): towards a new paradigm. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:574–588. doi: 10.2174/156720512800617982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley-Whitman MA., Lovell MA. Epigenetic changes in the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cencioni C., Spallotta F., Martelli F., Valente S., Mai A., Zeiher AM., Gaetano C. Oxidative stress and epigenetic regulation in ageing and age-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17643–17663. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker MP., LaFerla FM., Oddo SS., Brewer GJ. Reversible epigenetic histone modifications and Bdnf expression in neurons with aging and from a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Age (Disorder). 2013;35:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millan MJ. An epigenetic framework for neurodevelopmental disorders: from pathogenesis to potential therapy. Neuropharmacology. 2013;68:2–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deaton AM., Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grayson DR., Guidotti A. The dynamics of DNA methylation in schizophrenia and related psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:138–166. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming JL., Phiel CJ., Toland AE. The role for oxidative stress in aberrant DNA methylation in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:1077–1096. doi: 10.2174/156720512803569000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakulski KM., Dolinoy DC., Sartor MA., et al Genome-wide DNA methylation differences between late-onset Alzheimer's disease and cognitively normal controls in human frontal cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:571–88. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chouliaras L., Mastroeni D., Delvaux E., et al Consistent decrease in global DNA methylation and hydrowymethylation in the hippocampus of Azheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2091–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppieters N., Dieriks BV., Lill C., Faull RL., Curtis MA., Dragunow M. Global changes in DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in Alzheimer's disease human brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwata A., Nagata K., Hatsuta H., et al Altered CpG methylation in sporadic Alzheimer's disease is associated with APP and MAPT dysregulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:648–656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuso A., Cavallaro RA., Nicolia V., Scarpa S. PSEN1 promoter demethylation in hyperhomocysteinemicTgCRND8 mice is the culprit, not the consequence. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:527–535. doi: 10.2174/156720512800618053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuso A., Seminara L., Cavallaro RA., D'Anselmi F., Scarpa S. S-adenosyl-methionine/homocysteine cycle alterations modify DNA methylation status with consequent deregulation of PS1 and BACE and beta-amyloid production. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo X., Wu X., Ren L., Liu G., Li L. Epigenetic mechanisms of amyloid-β production in anisomycin-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Neurocience. 2011;194:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao JS., Keleshian VL., Klein S., Rapoport SI. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e132. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]