Abstract

PURPOSE

Depression is associated with lowered work functioning, including absence, productivity impairment, and decreased job retention. However, few studies have examined depression symptoms across a continuum of severity in relationship to the magnitude of work impairment in a large and heterogeneous patient population. This study assessed the relationship between depression symptom severity and productivity loss among patients initiated on antidepressants.

METHODS

Data were obtained from patients participating in the DIAMOND Initiative (Depression Improvement Across Minnesota: Offering a New Direction), a statewide quality improvement collaborative to provide enhanced depression care. Patients newly started on antidepressants were surveyed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a measure of depression symptom severity, the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI) a measure of productivity loss, and items on health status and demographics.

RESULTS

We analyzed data from the 771 patients who reported current employment. General linear models adjusting for demographics and health status showed a significant linear, monotonic relationship between depression symptom severity and productivity loss (p<.0001). Even minor levels of depression symptoms were associated with decrements in work function. Greater productivity loss also was associated with full-time vs. part-time employment status (p<.001), fair or poor health (p=.05), and “not coupled” marital status (p=.07).

CONCLUSIONS

This study illustrated the relationship between the severity of depression symptoms and work function, suggesting that even minor levels of depression are associated with productivity loss. Employers may find it beneficial to invest in effective treatments for employees across the continuum of depression severity.

Keywords: Depression, Severity, Work Impairment

INTRODUCTION

Depression is prevalent and incurs substantial indirect costs associated with lowered work functioning, including absence, productivity impairment, and even decreased job retention across a wide variety of occupations.1–4 In addition, several studies have shown that even minor or subthreshold depression (including dysthymia) is related to lowered work performance.5;6 Fewer studies have examined depression symptoms across a continuum of severity in relationship to the magnitude of work loss that includes both absence and productivity impairment. Simon et al.,7 found that among outpatients treated for bipolar disorder, depression severity was strongly and consistently associated with decreased probability of employment and illness absence days. Backenstrass et al.,8 characterized a spectrum of depressive symptoms across three increasing levels of severity: non-specific, minor, and major, and found an increasing number of illness absence days with each increased level of symptom severity. However, both studies had selected samples, limiting their generalizability (patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder and patients from six family practices in a small town near Heidelberg, Germany, respectively).

The goal of this study was to investigate further the relationship between a continuum of depression symptom severity and magnitude of productivity loss in a large heterogeneous and representative sample of outpatients initiating treatment for depression.

METHODS

Setting

Results presented here are from baseline data collected for a study of a statewide depression quality improvement initiative in Minnesota (Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction [DIAMOND]). All groups and clinics that intended to participate in the Initiative by implementing DIAMOND in their primary care clinics were invited to be in the DIAMOND Study. Eighty-eight clinics from 23 medical groups participated in the study. Details on the study design and methods are presented elsewhere.9

Patient recruitment and enrollment

All patients with health plan claims data showing them to be newly started on antidepressant medications at one of the participating clinics were identified on a weekly basis by the health plans and sent a letter about the study, providing a one week opportunity to opt out before being called by the research survey center to determine eligibility for participation and to complete a baseline survey by phone. Patients were eligible if they were over age 18, had filled a new antidepressant prescription (and none in the prior four months) from a primary care clinician at one of the participating clinics for the treatment of depression, and had a depression symptom severity score greater than or equal to seven on the Patient Health Questionnaire nine item screen (PHQ-9). Although part or full time employment was not an eligibility criterion for participation in the larger DIAMOND study, because the present study focused on the relationship between productivity loss at work and depression, we included in the analysis only the subset of patients employed for wages at least part time. Patients completing this survey at baseline were also asked for permission to re-survey them six months later.

The study protocol was reviewed, approved, and monitored by the HealthPartners Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Patient self-report surveys were used to provide the information on depression severity, work absence and productivity impairment, and health status (a single item asking patients to rate their overall health), as well as demographic characteristics of the subjects. The PHQ-9 was used to measure the severity of depression symptoms. It is widely accepted as a valid measure of depression severity.10–13 Questions about work function were obtained from the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI),14–16 a self-report measure of the amount of absence from work due to health problems, as well as productivity impairment while at work (“presenteeism”) experienced during the previous seven days. Additional measures were computed to estimate the percent of work time missed due to health, percent impairment while working due to health, and percent of overall productivity loss due to health.16 Percent work time missed due to health, a measure of absenteeism, was calculated as the hours missed during the previous seven days divided by the hours missed plus the hours worked during this period. Percent impairment while working due to health, a measure of presenteeism, was calculated as a 10-point rating of degree of impairment while at work divided by 10. The number of hours of productivity impairment at work was calculated as the hours actually worked multiplied by the percent impairment while at work. The proportion of expected work time that was missed or impacted due to health problems over the previous seven days (productivity loss) was calculated as the percent of work time missed plus the percent of time at work multiplied by impairment while there.

RESULTS

Patient enrollment and demographic characteristics

During a 25-month period, 11,889 patient names were submitted to the research survey center. However, 41% of these patients could not be contacted, and of those who agreed to be screened, 75% did not meet eligibility criteria for the study. The study enrollment data are shown in Table 1, indicating that to date, 1,168 patients have been contacted, assessed for eligibility, consented, and enrolled. We analyzed data on the relationship between depression and work impairment for the sub sample of 771 patients (66%) who reported that they were working for wages either full or part time at the time of their interview. Demographic characteristics of the enrolled and employed patients are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Pre-Intervention Patient Enrollment

| N | % of total | % of remaining | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact information from health plan | 11,889 | ||

| Contact made with member | 7,023 | 59.1 | 59.1 |

| Eligibility assessed | 4,741 | 39.9 | 67.5 |

| Study eligible | 1,180 | 10.0 | 24.9 |

| Consented | 1,173 | 9.9 | 99.4 |

| Baseline complete | 1,168 | 9.8 | 99.6 |

| Working for pay | 771 | 6.5 | 66.0 |

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Enrolled Pre-Intervention Patients Working for Pay

| N | 771 |

| Female | 74.8 |

| Age M (SD) | 42.5 (12.4) |

| Hispanic | 3.0 |

| Race | |

| Native American | 0.5 |

| Asian | 0.8 |

| Black, African-American | 3.8 |

| Multiracial | 1.4 |

| Native Hawaiian, Alaska Native | 0.4 |

| Other | 1.6 |

| Unknown | 0.3 |

| White | 91.3 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 90.2 |

| Education | |

| Grade 1–11 | 3.9 |

| High School | 21.4 |

| Some college | 39.3 |

| College graduate | 24.0 |

| Graduate degree | 11.4 |

| Employment | |

| Employed for wages | 90.1 |

| Self-employed | 8.0 |

| Student | 1.0 |

| On disability | 0.8 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 52.8 |

| Divorced | 15.8 |

| Separated | 3.2 |

| Unmarried couple | 8.4 |

| Widowed | 1.7 |

| Never married | 18.0 |

| Functional Health Status | |

| Excellent | 7.0 |

| Very Good | 29.6 |

| Good | 40.6 |

| Fair | 18.5 |

| Poor | 4.3 |

Depression symptoms

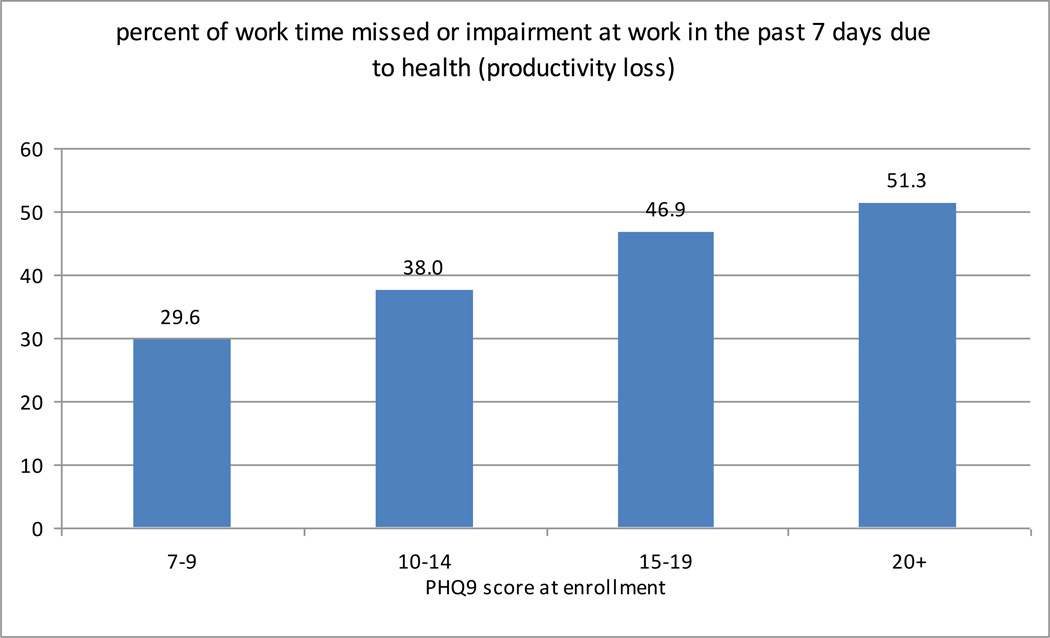

We divided PHQ-9 scores into four ordinal categories corresponding to increasing levels of depression severity. The PHQ-9 category of 7–9 is equal to mild or minor symptoms of depression, a score of 10–14 is in the moderate depression range, 15–19 is consistent with major depression and considered a diagnostic threshold, and 20+ is considered severe depression. The plurality of patients (293 / 38%) had scores in the moderate range of depression symptoms, followed by scores in the minor (263 / 34%), major (159 / 21%) and severe (57 / 7%) range. The mean PHQ-9 score was 12.2 (sd = 4.3).

Work loss and productivity

Table 3 presents descriptive data on the WPAI items. Patients reported that over the previous seven days, an average of 3.1 hours, or 8.2 percent of their total usual working hours were missed due to health conditions. The average rating of the degree of impairment while at work was 3.5 on the 10-point scale, representing 35.2 percent of total hours worked, or 12.1 hours of productivity impacted while at work. The proportion of expected work time that was missed or impacted due to health problems over the previous seven days (productivity loss) represented an average of 37.8 percent of employees’ usual work hours, or 14.2 hours of work missed or work time impaired due to health. Note that the value of productivity loss as calculated (and described in the Methods section) is not the sum of absenteeism + presenteeism, because the latter only includes hours actually at work.

Table 3.

WPAI Item and Scale descriptives

| N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| During the past seven days, how many hours did you miss from work because of your health problems? | 740 | 3.1 | 8.0 |

| During the past seven days, how many hours did you actually work? | 740 | 33.8 | 15.5 |

| During the past seven days, how much did your health problems affect your productivity while you were working? | 721 | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| Thinking of your regular job, how many days in the past seven days were you limited in the amount of work you could do, accomplished less than you would like, or days you could not do your work as carefully as usual? | 737 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| % of work time missed due to health (absenteeism) | 740 | 8.2 | 20.5 |

| % impairment at work due to health (presenteeism) | 720 | 35.2 | 26.4 |

| % of work missed or work time impaired due to health (absenteeism or presenteeism) | 719 | 37.8 | 27.5 |

| Hours of impairment at work due to health | 720 | 12.1 | 11.0 |

| Hours of work missed or work impaired (productivity loss) due to health | 719 | 14.2 | 12.6 |

Relationship between PHQ-9 and WPAI

Figure 1 graphically represents the relationship between each category of depression symptoms and productivity loss, respectively. It illustrates the strong linear relationship between depression symptom severity and combination of work loss and productivity impairment.

Figure 1.

Productivity Loss (Absenteeism and Presenteeism combined) by PHQ-9 Score at Enrollment*

*For comparison purposes, productivity loss norms for individuals without depression or other chronic conditions is 8.0%

We next estimated general linear models (PROC GLM, SAS™ version 9.1.3) to investigate the relationship between depression symptoms and productivity loss while adjusting for self-reported health status and several demographic variables. This analytic approach was chosen after determining that there were no significant clustering effects and therefore, the GLM is equivalent to a mixed model. Because the relationships between depression and both work loss and productivity were similar, we chose to use the combined variable, productivity loss, in our subsequent multivariate modeling. The PHQ-9 scores and productivity loss were both treated as continuous variables in the model. Demographic characteristics and self-reported health status were included as covariates. Demographic variables included age, gender, race (non-Hispanic white vs. Hispanic or non-white), education (high school or less vs. some college or more), employment status (full vs. part time), and marital status (coupled vs. single). Self-reported health status was categorized as a combination of “excellent,” “very good, ” and “good” vs. “fair” and “poor.” Interaction terms between PHQ-9 and covariates were tested and none were found to be significant so they were eliminated from the model. The overall model containing all covariates was significant, F = 10.26, p<.0001 (model R2 = .105). Table 4 displays the individual variables in the model. Higher PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with increased productivity loss (p<.0001). In addition, greater productivity loss was associated with full-time vs. part-time employment status (p<.001), fair or poor health (p=.045), and “not coupled” marital status (p=.071).

Table 4.

General Linear Model Showing Relationship of Depression Severity (PHQ-9 Score), Demographics, and Health Status to Productivity Loss*

| Parameter | Estimate | Error | t Value | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 36.50 | 1.74 | ||

| PHQ-9 Score** | 1.65 | 0.24 | 6.98 | <.0001 |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| Gender Male | 1.89 | 2.32 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Minority | 3.36 | 3.30 | 1.02 | 0.31 |

| Health Fair/Poor | 4.80 | 2.39 | 2.01 | 0.05 |

| Education – High School or Less | −1.44 | 2.30 | −0.62 | 0.53 |

| Employed Part-time | −9.85 | 2.60 | −3.79 | <.001 |

| Marital Status: Not Coupled | 3.73 | 2.06 | 1.81 | 0.07 |

Productivity loss is defined as the combination of absenteeism (percent of time missed in the past 7 days due to health) and presenteeism (percent impairment at work in the past 7 days due to health). These measures were obtained from the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI).

The general linear model shows the relationship between PHQ-9 Scores and productivity loss adjusted for all other variable listed in the table.

Because our sample of 771 employed individuals represented only 66% of those with complete baseline data for this analysis, we conducted a sub-analysis to determine whether employment status was related to depression severity among working age participants (ages 18 – 64). Results indicated that mean PHQ-9 scores were higher among the 325 study participants reporting no employment (M = 13.30, SD = 4.90) vs. the 757 study participants reporting full- or part-time employment (M = 12.17, SD = 4.31), t = 3.62, df = 549.2, p=.0003).

DISCUSSION

Baseline data from this large sample of patients demonstrate a linear, monotonic relationship between depression symptom severity and productivity loss; that is, as depression symptom severity increased, the amount of productivity loss increased in a linear relationship. Specifically, we found that for every one-point increase in patients’ PHQ-9 scores, they experienced an additional mean productivity loss of 1.6%. This relationship was observed after adjusting for, and not modified by, demographics and self-reported health status.

The finding of greater productivity loss for those employed full-time vs. part-time may be explained by the fact that full-time employees have less flexibility in their schedules, requiring the use of sick absence days and working while negatively impacted by depression symptoms. Greater productivity loss among those reporting fair or poor health is consistent with literature on the impact of health conditions on work function. The trend toward greater productivity loss among those not coupled may represent less availability of instrumental social support (e.g., assistance with tasks that require time off from work) and/or emotional support that buffers work stress and its potentially deleterious impact on productivity.

Although the relationship between depression symptoms and both work loss and presenteeism appeared similar, the relative impact of each differed. The percent of work loss reported over the last seven days ranged from 4% (PHQ-9 scores from 7–9) to 17% (PHQ-9 scores of 20 or more), whereas the percent of productivity impairment over the same period ranged from 28% (PHQ-9 scores from 7–9) to 47% (PHQ-9 scores of 20 or more). The greater productivity impairment reported likely reflects the limits on sick days available for employees. It also suggests that in relative terms, presenteeism due to depression may represent a more significant problem than absenteeism for employers.

The magnitude of productivity loss in this sample of patients (38%) is large compared to normative data for the WPAI that includes individuals without health conditions (8%), as well as those with such conditions as diabetes (15%), asthma (15%), back pain (16%), obesity (18%), angina (20%), and chronic pain (22%) (Personal Communication, Steve Schwartz, Director of Research, Health Media, 8/25/10). The greater productivity loss reported by patients in this study may be due in part to the fact that the study sample was recruited from outpatient clinics during treatment initiation when depression symptoms were presumably at a peak and recent work function was most impacted. In fact, productivity loss for various health conditions is greater when reported in observational studies or clinical trials involving these patients as compared with population-based surveys.17;18 For example, recent studies using the WPAI with clinic-based patient samples show 28% productivity loss associated with severe asthma, 38% for Crohn’s disease and 20% for allergic rhinitis.19 Moreover, similar to our findings for depression, the majority of these studies show increased productivity loss associated with increased severity of the condition.

The finding of greater depression severity among the 34% of participants not employed raises the question of whether and how depression severity may contribute to unemployment. Symptoms of depression (lack of initiative, poor self-esteem, etc.) are a significant barrier to getting and/or holding a job. Therefore, the relationship of depression severity and productivity loss we report for only the employed sample may well underestimate the impact of depression on work function and employment status in general.

This study adds to the growing body of literature suggesting the importance of treating depression in order to restore psychosocial function in addition to remit symptoms.5 These studies have suggested that even minor depression symptom severity is associated with work impairment, and although work performance improves in proportion to depression symptom remission following treatment,20;21 it remains consistently lower among individuals showing clinical improvement in depression compared to non-depressed controls.22

Fortunately, high quality depression treatment has been found to reduce symptoms, to improve work function, and to be cost effective.23 Non-pharmacologic treatments may be of benefit even for minor depression, as demonstrated by Wang’s randomized trial of telephonic care management of workers with depression24 (although the benefit from pharmacologic treatment of minor depression is less evident).25

Considering the strength of the relationship between depression symptoms and work performance, our findings also underscore the potential utility of using the PHQ-9 to provide health professionals with insights about not only depression severity, but also about work function. Primary care providers who better appreciate the impairment in work function associated with the continuum of minor to severe symptoms of depression may have an extra incentive to treat patients more intensively and to full remission wherever possible, rather than accepting minor degrees of improvement. This may be particularly important given the problem of clinical inertia that depression treatment often poses, i.e., lack of follow-up with and treatment adjustments for patients initiated on antidepressants. Moreover, results from this study indicate that different levels of depression symptom severity can be directly translated into magnitude of work impairment. Using a relatively easy-to-administer instrument such as the PHQ-9 can serve both to help primary care providers assess depression in their patients, and once it is identified, to understand at a more precise level how much work impairment may be associated with different levels of depression symptom severity. Given the importance of work in peoples’ lives, providers might wish to ask patients with high PHQ-9 scores about how their depression is impacting their work function, how their work might affect their depression, and how treatment for depression or other interventions might help patients not only feel better but also function better at work and for that matter, in their lives overall. Focusing the discussion on the functional impact of depression (especially work function) may provide depressed patients who are hesitant to acknowledge or treat their depression additional motivation to engage in treatment.

Taking the perspective of employers, these results provide more tangible evidence of the potential labor costs of even minor depression symptoms and the potential to realize a return on investment from assuring that their employees who experience a broader range of depression symptom severity than might typically be considered to warrant treatment receive the most effective treatments possible.24;26;27

The results reported in this paper have both strengths and limitations. This large real world sample has been obtained from members of a majority of health plans (including people on Medicaid products) across the state of Minnesota within the context of a natural experiment, using minimal inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, the subjects constitute a broadly representative sample of depressed primary care patients from a variety of backgrounds, income levels, and occupational categories. Therefore, the results should be widely generalizable (with the exception of race and/or ethnicity which have limited diversity in this geographic region). In addition, our ability to examine the relationship between the actual level of self-reported depressive symptomatology and the amount of work loss and productivity impairment is more informative than many studies that examine only work loss and productivity impairment among patients who receive a diagnosis of depression or who reached a threshold of symptom severity classifying them as having major depression. These findings do suggest that even subclinical levels of depression are associated with work absence and productivity impairments.

One limitation of this study is the lack of detailed data on other health or mental health conditions that might be associated with work loss and productivity impairment. The inclusion of self-reported health status provides a less precise measure of disease burden than actual data about medical comorbidities. Unfortunately, we did not have access to comorbidity data across all health plans participating in the study. Regarding the impact of psychiatric comorbidities other than depression on productivity loss, future studies might benefit from using the recently published M3 instrument to assess a greater number of mental disorders than the PHQ-9.28

An additional limitation is that the analyses were restricted to those reporting at least some employment, excluding those not in the labor force (e.g., retirees, students, etc.), because our focus was on work function. Moreover, this study does not provide data on individuals with PHQ-9 scores < 7 (i.e., not depressed). However, as mentioned earlier, normative data on productivity loss for non-depressed individuals with no other chronic medical conditions is 8%, which is considerably lower than our findings of 29.6% for those with minor depression (PHQ-9 scores ranging from 7–9).

Analysis of the relationship between levels of depression symptoms and broad self-report measures of general functional status across the larger sample of study patients is beyond the scope of this paper, but will be reported on in a subsequent paper. Finally, because insufficient numbers of study patients have reached the follow up assessment time frame, data are not available to examine the relationship between potential improvements in depression symptoms and work performance, and whether this relationship differs depending on the level of initial depression symptom severity reported. We look forward to reporting these results when such data become available.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated the relationship between levels of depression symptoms and productivity loss, suggesting that even minor levels of depression are associated with decrements in work function. The significant relationship between depression symptoms, as measured by the widely-used PHQ-9, and impairments in work function, raises the possibility of using the PHQ-9 as a tool to assess both depression symptoms and work function in patients. Taking the perspective of employers, promoting evidence-based depression management programs to employees experiencing even minor depression may have the potential to improve reduce work loss and productivity impairment, thus yielding a return on investment in such programs.

Ultimately, the goal of this work is to understand how effective depression care can improve both depression symptoms and work function. Once sufficient numbers of patients have completed six month follow-up data, we also will be able to explore the relationship between depression symptom remission and improvement in work function.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING SUPPORT

This research was funded by grant #5R01MH080692 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

This research would not have been possible without the active support of multiple payers (Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, First Plan, HealthPartners, Medica, Minnesota Dept. of Human Services, Preferred One, and U Care), as well as the twenty-four medical groups who provided information to connect patients to specific study clinics and cooperated with evaluation of patients reporting suicidal thoughts on the PHQ9. Patient subject recruitment and surveys have been sustained by Colleen King and her wonderful staff at the HPRF Data Collection Center.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None of the authors of this manuscript have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berndt ER, Finkelstein SN, Greenberg PE, et al. Workplace performance effects from chronic depression and its treatment. J Health Econ. 1998;17:511–535. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al. Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Aff (Millwood ) 1999;18:163–171. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. Unemployment, job retention, and productivity loss among employees with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1371–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. The clinical and occupational correlates of work productivity loss among employed patients with depression. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:S46–S55. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000126684.82825.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katon W. The impact of depression on workplace functioning and disability costs. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:S322–S327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin JK, Blum TC, Beach SR, Roman PM. Subclinical depression and performance at work. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00789116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unutzer J, Operskalski BH, Bauer MS. Severity of mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:718–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backenstrass M, Frank A, Joest K, Hingmann S, Mundt C, Kronmuller KT. A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solberg LI, Glasgow RE, Unutzer J, et al. Partnership research: a practical trial design for evaluation of a natural experiment to improve depression care. Med Care. 2010;48:576–582. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbea62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattke S, Balakrishnan A, Bergamo G, Newberry SJ. A review of methods to measure health-related productivity loss. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly Associates. [Accessed 11/8/10];Health Outcomes Research. http://www reillyassociates net.

- 17.Bolge SC, Balkrishnan R, Kannan H, Seal B, Drake CL. Burden associated with chronic sleep maintenance insomnia characterized by nighttime awakenings among women with menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2010;17:80–86. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181b4c286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erickson SR, Guthrie S, Vanetten-Lee M, et al. Severity of anxiety and work-related outcomes of patients with anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1165–1171. doi: 10.1002/da.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Blanc PD, Hayden ML, Bleecker ER, Chawla A, Lee JH. Assessing productivity loss and activity impairment in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Value Health. 2008;11:231–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aikens JE, Kroenke K, Nease DE, Jr, Klinkman MS, Sen A. Trajectories of improvement for six depression-related outcomes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, de GR, et al. Mediators of the association between depression and role functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adler DA, McLaughlin TJ, Rogers WH, Chang H, Lapitsky L, Lerner D. Job performance deficits due to depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1569–1576. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang PS, Patrick A, Avorn J, et al. The costs and benefits of enhanced depression care to employers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1345–1353. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang PS, Simon GE, Avorn J, et al. Telephone screening, outreach, and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1401–1411. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bush T, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. Who benefits from more structured depreessiona treatment? Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34:247–258. doi: 10.2190/LF18-KX2G-KT79-05U8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaynes BN, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Weir S, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic validity of the m-3 checklist: a brief, self-rated screen for depressive, bipolar, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:160–169. doi: 10.1370/afm.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]