Abstract

The gastrointestinal tract is a vast neuroendocrine organ with extensive extrinsic and intrinsic neural circuits that interact to control its function. Circulating and paracrine hormones (amine and peptide) provide further control of secretory, absorptive, barrier, motor and sensory mechanisms that are essential to the digestion and assimilation of nutrients, and the transport and excretion of waste products. Specialized elements of the mucosa (including enteroendocrine cells, enterocytes and immune cells) and the microbiome interact with other intraluminal contents derived from the diet, and with endogenous chemicals that alter the gut's functions. The totality of these control mechanisms is often summarized as the brain–gut axis. In irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is the most common gastrointestinal disorder, there may be disturbances at one or more of these diverse control mechanisms. Patients present with abdominal pain in association with altered bowel function. This review documents advances in understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms in the brain–gut axis in patients with IBS. It is anticipated that identification of one or more disordered functions in clinical practice will usher in a renaissance in the management of IBS, leading to effective therapy tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

|

Michael Camilleri, M.D., is consultant in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Professor of Medicine, Pharmacology, and Physiology, and Atherton and Winifred W. Bean Professor, and Executive Dean of the Department of Development at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. His research interests are in the field of clinical enteric neuroscience, the study of physiology and pathophysiology of human gastrointestinal motor and sensory functions and obesity, and the development of novel therapeutic approaches for gastrointestinal disorders and obesity. He is internationally recognized for his clinical contributions to gastroenterology, his extensive research program and his publications in the scientific literature.

Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a vast neuroendocrine organ with extensive extrinsic and intrinsic neural circuits that interact to control its function. Circulating and paracrine hormones (amine and peptide) provide further control of secretory, absorptive, barrier, motor and sensory mechanisms that are essential to the digestion and assimilation of nutrients, and to the transport and excretion of waste products. Specialized elements of the mucosa (including enteroendocrine cells, enterocytes and immune cells) and the microbiome interact with other intraluminal contents derived from the diet, and with endogenous chemicals that alter the gut's functions.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is currently defined by symptoms (i.e. abdominal discomfort associated with bowel disturbances) in the absence of organic disease on routine testing. IBS affects about 11% and diarrhoea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) about 5% of the US population (Lovell & Ford, 2012) and often impair quality of life (Mönnikes, 2011). The disturbances of function that result in these different symptom phenotypes arise mainly in the colon and, to a lesser extent, the small intestine. Understanding the pathophysiological disorders in IBS requires a brief introduction to the neural and hormonal control of GI and colonic functions.

Neural control of GI and colonic functions

Myogenic factors regulate the electrical activity generated by GI smooth muscle cells. Contraction, relaxation and integration of smooth muscle cell functions in the gut are modulated by extrinsic [the central nervous system (CNS) and autonomic nerves] and enteric (the enteric nervous system) nerves. Extrinsic neural control consists of the vagal and sacral parasympathetic nerves (excitatory to non-sphincteric muscle) and the thoracolumbar sympathetic supply (excitatory to sphincters, inhibitory to non-sphincteric muscle) arising from T5 to L2 of the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord. The prevertebral ganglia integrate afferent impulses between the gut and the CNS, and provide additional reflex control of the abdominal viscera.

The enteric nervous system is an independent nervous system consisting of ∼100 million neurons organized in ganglionated plexuses. The two main plexuses are the myenteric and submucosal plexuses. Auerbach's (or myenteric) plexus is situated between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers and is involved in control of GI motility. The submucosal, or Meissner's, plexus controls absorption, secretion and mucosal blood flow. Other ganglionated plexuses are not as anatomically defined in different regions of the gut. The enteric nervous system also plays a role in visceral sensation and in integration of peristalsis.

Interstitial cells of Cajal are non-neural pacemaker cells in the wall of the gut at the interface between the enteric nervous system and smooth muscle cells. Electrical control activity spreads through the contiguous segments of the gut that form muscle syncytia and convey the electrical stimulus through gap junctions and through neurochemical activation. There are excitatory (e.g. acetylcholine, substance P) and inhibitory (e.g. nitric oxide, somatostatin) transmitters. The unit of motor function in the gut is the peristaltic reflex, which involves sensation of the luminal stimulus (chemical or mechanical), transduction of the sensation through intrinsic primary afferent neurons, and an integrated excitatory response above the site of distension and relaxatory response below it. Interneurons (e.g. opioids or somatostatin) coordinate these functions.

Visceral sensation involves a three-neuron chain that conveys afferent function from the GI tract and through spinal and brainstem or thalamic synapses, and conveys information to affective and consciousness centres in the brain.

Hormonal control of GI and colonic functions

The GI tract is a vast endocrine organ. The presence of food, products of digestion and endogenous substances involved in the process of intraluminal digestion (e.g. bile acids) activate taste receptors (e.g. gustducins) or specific receptors [e.g. G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1)] to activate the secretion of a plethora of peptides and amines that serve to mediate extrinsic reflexes (e.g. involving vagal afferent pathways), enteroendocrine cell secretion, local paracrine effects that mediate secretion of fluid, electrolytes or digestive enzymes, and activation of sensory mechanisms that mediate local or long reflex responses. In addition, circulating hormones influence gut functions including secretion (e.g. acid, pancreatic enzymes) and motor functions.

Key findings in IBS

This review discusses the neurohormonal control of GI functions and alterations in extrinsic neural and neurohormonal control mechanisms that result in pathophysiological and clinical manifestations of IBS, based on published evidence.

Alterations in control mechanisms of the brain–gut axis have been documented in patients with IBS. These include disturbances of colonic transit [e.g. 45% of patients with IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D) have accelerated and 20% of patients with IBS with constipation (IBS-C) have delayed colonic transit], visceral hypersensitivity [20–95% in different studies (Camilleri et al. 2008; Mayer, 2008; Mayer & Tillisch, 2011; Camilleri, 2012)], and CNS hypervigilance, which are traditional underpinnings of the syndrome and of visceral pain in IBS. Although persistent nociceptive mechanisms are activated in some patients (Zhou & Verne, 2011), IBS symptoms are not specific to a single aetiological mechanism, but are manifestations of several luminal and mucosal factors that perturb motor, sensory, barrier, immune and other functions in the small intestine or colon. Such ‘irritation’ leads to the symptoms and pathophysiology of IBS, which have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (Camilleri, 2012) and are summarized in Table 1, which also documents the interaction of genetic factors that may modify these functions. Thus, several peripheral pathophysiological mechanisms, the factors involved and clinical correlates are identified, including: colonic motility; rectal evacuation disorder; colonic motor and sensory responses to feeding; small bowel and colonic sensing of intraluminal chemicals and the elicited responses; small bowel and colonic mucosal barrier function (permeability); mucosal immune activation, and the colonic microbiome. Thus, 10 important intestinal and colonic functions or predisposing factors may, individually or through interactions, lead to IBS; they are described briefly in the next section.

Table 1.

Peripheral factors in the biology of irritable bowel syndrome [reproduced from Camilleri (2012) N Engl J Med]

| Peripheral mechanism | Pathophysiology | Examples of factors involved | Comments and clinical correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonic motility | Accelerated or delayed colonic transit; may be secondary to secretory mechanism | Neuromuscular dysfunction Enteroendocrine cell products (e.g. 5-HT, granins) Organic acids (BA, SCFAs) Genetic predisposition: BA synthesis (Klothoβ); GUCY2C mutation | Up to 45% of IBS-D and 20% of IBS-C |

| Colonic motor and sensory response to feeding | Neurally (e.g. vagally) mediated induction of colonic HAPCs, increased ileocolonic transit, increased rectal sensitivity | Fat content of meal; high caloric content | Contributes to postprandial pain, urgency, diarrhoea |

| Small bowel and colonic sensing and responses | Activation of local secretory or motor reflexes and sensory mechanisms | Food stimulation of enteroendocrine cell products, organic acids (BA, SCFAs) | Typically associated with diarrhoea, bloating, pain |

| Rectal evacuation disorder | Failure of rectal emptying with reflex inhibition of colonic motor function | Anismus, pelvic floor dyssynergia, descending perineum syndrome | Typical IBS-C symptoms and incomplete evacuation and straining reversed with pelvic floor relaxation |

| Small bowel mucosal permeability | Increased permeability; altered expression (mRNA, protein) of tight junction proteins | Prior gastroenteritis; atopy; food intolerance (e.g. gluten, ?FODMAP); stress | Typically associated with IBS-D; may increase fluid secretion or activate sensory mechanism |

| Colonic mucosal permeability | Increased permeability; altered expression (mRNA, protein) of tight junction proteins | Malabsorbed CHO or fat increasing SCFAs BA malabsorption (25% IBS-D) Immune activation Genetic predisposition: Inflammation/immune activation (e.g. TLR9, TNFSF15), BA synthesis (Klothoβ) | Typically associated with IBS-D; may increase fluid secretion or activate sensory mechanism |

| Mucosal immune activation | Increased permeability; activation of submucosal secretory reflexes and sensory mechanisms | Prior gastroenteritis Mast cells T lymphocytes Circulating cytokines | Typically associated with IBS-D and abdominal pain |

| Colonic microbiome | Production of SCFAs with effects on motor, secretory and sensory functions | Increased Firmicutes or ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes Modified by antibiotics, probiotics BA influence microbial species | Associated abdominal bloating, pain, diarrhoea |

Abbreviations: BA, bile acid; CHO, carbohydrates; FODMAP, fermentable oligo-di-monosaccharides and polyols; HAPCs, high-amplitude propagated contractions; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea; SCFAs, short chain fatty acids.

Ten general intestinal and colonic dysfunctions in IBS

The colonic response to feeding (‘gastrocolonic’ response) refers to a vagally mediated, predominantly motor stimulation of the distal small intestine, proximal and distal colon that results in the propulsion of colonic content (Kerlin et al. 1983) and is a cause of the association of symptoms with meal ingestion. This ‘long reflex’ involves receptors that ‘taste’ nutrients to activate vagal afferents (Rozengurt, 2006; Farré & Tack, 2013), and brainstem nuclei stimulate spinal pathways and sacral parasympathetic supply to the entire colon, reaching the proximal colon through ascending intra-colonic nerves (Christensen & Rick, 1987).

Rectocolonic inhibition results in the inhibition of the motor activity of the proximal colon to retard transit. It is usually initiated by rectal retention [most typically in disorders of rectal evacuation caused by pelvic floor dyssynergia, which mimics IBS with constipation (Mollen et al. 1999)]. Based on experimental animal studies, this function involves reflexes that relay at the levels of the prevertebral ganglia (Kreulen & Szurszewski, 1979) and the spinal cord (Morgan et al. 1986).

Visceral afferents involve intrinsic and extrinsic pathways leading to reflex functions and the conscious perception of symptoms such as pain and bloating (Gebhart, 2000; Azpiroz et al. 2007). Several brain centres are preferentially activated or deactivated in response to visceral stimuli; for example, there is greater activation of the insula and reduced deactivation in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex during noxious distensions of the rectum (Larsson et al. 2012). Recent studies suggest that there are brain dysfunctions, volumetric differences, and differences in connectivity or ‘betweenness’ in brain centres between health and IBS (Labus et al. 2014). The functional and clinical relevance of these differences is the subject of ongoing research.

Prior infections activate pathophysiological processes that result in the manifestations of IBS (Spiller, 2003).

Alterations in mucosal permeability and reduced barrier function are associated with evidence of visceral hypersensitivity in IBS (Camilleri et al. 2012).

Local synthesis, transporter and inactivation mechanisms involving peptides and amines in the mucosa impact the local motor (e.g. peristaltic reflex), secretory, absorptive, sensory and barrier functions (e.g. serotonin and serotonin transporter proteins) (Mawe & Hoffman, 2013).

Enteric microbiota, including both commensal and pathogenic organisms, can be influenced by the brain through changes in GI motility and secretion, and intestinal permeability, or directly by signalling molecules released into the gut lumen from cells in the lamina propria (enterochromaffin cells, neurons, immune cells). Conversely, communication from enteric microbiota to the host can occur via multiple mechanisms, including receptor-mediated signalling in epithelial cells and, when intestinal permeability is increased, through direct stimulation of host cells in the lamina propria (Rhee et al. 2009). Thus, there are bidirectional communications between the brain and the microbiota (Cryan & Dinan, 2012) (Fig. 1). The potential for gut microorganisms to influence brain responses in humans has been illustrated by the finding of reduced activation of brain centres involved in emotional responses with the administration of fermented milk products with probiotics (Tillish et al. 2013). In animal models, products of microbiota may also affect the excitability of enteric neurons (Bercik et al. 2011) and vagal afferents (Bravo et al. 2011).

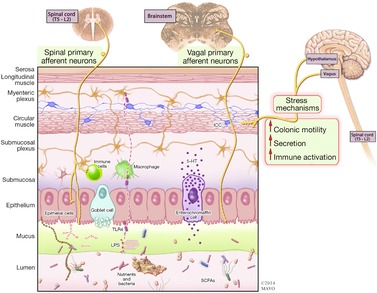

Figure 1. Gut mucosal barrier, microbiome and brain interactions.

There is bidirectional communication between gut microbiota and the brain. Hypothalamic and stress mechanisms stimulate colonic motility, increasing colonic transit. Gut microbial signals and antigens, short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (and products of nutrient digestion), mechanical stimulation, toxins [e.g. lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)] and irritants (endogenous or exogenous) alter mucosal permeability. These result in secondary effects such as stimulation of enterochromaffin cells, activation of immune mechanisms, production of cytokines, and stimulation of intrinsic primary afferent neurons and spinal or vagal afferents that commence the relay of sensory information to the brain.

Immune activation and minimal inflammation (Öhman & Simrén, 2010), manifesting as increased T lymphocytes and mast cells in rectal mucosa in patients with IBS, were associated with increased intestinal permeability (Spiller et al. 2000) and functional alterations of several components of the host mucosal immune response to microbial pathogens (Aerssens et al. 2008).

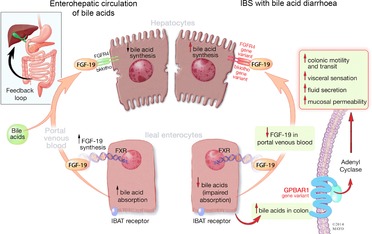

Bile acids, which are intraluminal factors involved in nutrient digestion, activate secretion of enteroendocrine cell products [e.g. 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)], increase mucosal permeability, stimulate colonic motility (Bampton et al. 2002) and defecation, and increase sensation, at least in part, by stimulation of specific receptors [GPBAR1 (Alemi et al. 2013)] (Fig. 2) or through the detergent properties of bile acids (Chadwick et al. 1979), activating sensory pathways.

Figure 2. Enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea (IBS-D).

Ileal enterocytes absorb bile acid through a receptor-mediated process [ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT)]. Intracellular bile acids activate farnesoid-γ receptor to increase FGF-19 synthesis. FGF-19 in portal circulation downregulates hepatocyte bile acid synthesis. Disorders of FGF-19 synthesis by ileal enterocytes or genetic variations of FGFR4 or β-klotho result in excess bile acid concentration in the colon, resulting in activation of the G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1) with enteroendocrine cell stimulation [(e.g. release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] and stimulation of colonic motility with acceleration of colonic transit, activation of visceral sensation and fluid secretion (through increased intracellular cAMP, increased mucosal permeability or chloride ion secretion). Gene variation in GPBAR1 is associated with increased colonic transit in IBS-D.

Non-absorbed complex carbohydrate (2–20% of dietary starch) (Stephen et al. 1983) leads to the intraluminal production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that stimulate colonic motility, in part, through stimulation of 5-HT secretion (Fukumoto et al. 2003). SCFAs enhance colonic fluid absorption and are generally decreased in IBS-D, except for the SCFA butyrate (Treem et al. 1996); faecal flora from IBS-D produce less SCFA in in vitro fermentation with various carbohydrates and fibres, such as lactulose, starch, pectin and hemicellulose. Reduced pro-absorptive SCFAs may contribute to diarrhoea in IBS-D.

Enteric neurohormonal control in IBS

Neural, hormonal and peptidergic mechanisms that mediate or integrate these important functions have been investigated in IBS, and are detailed in the next section; however, the integration of the different mechanisms, and adaptive or compensatory responses are the subjects of ongoing research. The literature documenting examples of altered functions of peripheral hormones, amines and peptides in IBS is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of altered functions of hormones, amines, and peptides in irritable bowel syndrome

| Mechanisms | Pathophysiology | Release and distribution | Comments and clinical correlates | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI mucosal and faecal granins | Chromogranins (Cg) or secretogranins (Sg) in secretory granules mobilize release of peptide hormones from EC cells | Release of, e.g. 5-HT, PYY, somatostatin (SS), melatonin from secretory granules | IBS-D or IBS-A higher faecal CgA, SG II and III and duodenal CgA cell density; changes not specific for IBS; higher CgA and SG associated with faster colonic transit and weakly with symptoms; lower PYY, higher SS in mucosal biopsies in IBS | Spiller et al. 2000; Montero-Hadjadje et al. 2009; El-Salhy, 2012; Öhman et al. 2012; El-Salhy et al. 2013 |

| Serotonin conventional functions | 5-HT is derived primarily from the gut: mediates intrinsic reflexes (e.g. stimulates motility, secretion and vasodilation); activation of extrinsic vagal and spinal afferents that activate extrinsic reflexes and sensation | Circulating 5-HT represents the 5-HT that does not undergo reuptake by the serotonin transporter (SERT) in the cells of the epithelial lining or in platelets | Plasma postprandial 5-HT elevated in IBS-D, and PI-IBS; reduced in IBS-C; platelet SERT uptake is disrupted in IBS-D; direct correlations between plasma 5-HT and sigmoid colonic motility, speed of colonic transit and colonic pain and stool thresholds | Bellini et al. 2003; Houghton et al. 2003, 2007; Atkinson et al. 2006; Franke et al. 2010; Foley et al. 2011; Mawe & Hofmann, 2013; Shekhar et al. 2013 |

| Serotonin non-conventional actions | Promoting inflammation, development and maintenance of neurons and ICC | Mucosal 5-HT elevated in IBS-C; mucosal SERT mRNA expression and immunoreactivity varies between studies | Coates et al. 2004; Camilleri et al. 2007; Kerckhoffs et al. 2012; Mawe & Hofmann, 2013 | |

| Glucagon-like-peptide 1 | Formed in ileal and colonic L-cells from a proglucagon precursor molecule | Secreted into the bloodstream in response to CHO and fat | Main action is nerve-dependent inhibition of GI motility, mediated by afferent vagal fibres and efferent nerves; inhibits MMCs and reduces pain scores in IBS without delaying colonic transit | Tolessa et al. 1998; Hellström et al. 2008; Bucinskaite et al. 2009; Camilleri et al. 2012 |

| Corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) | Produced in hypothalamus, activating release of stress hormones and also having direct effects on colonic motor, secretory and immune functions | Secreted into HPA and ‘spillover’ to systemic circulation in response to stress | Upregulation of CRF-R1 signalling with expected abdominal pain Pharmacological studies (with CRH agonists) in humans demonstrate exaggerated effects in colonic motility and visceral perception, and brain (EEG) responses Improved colonic sensorimotor function and brain function in response to a peptide CRH antagonist, with effect of CRF1 antagonist on colonic transit in IBS | Fukudo et al. 1998; Sagami et al. 2004; Tayama et al. 2007; Sweetser et al. 2009; Labus et al. 2013 |

| Melatonin | Produced by pineal gland and enteroendocrine cells | Released locally in the intestine to modulate transmembrane transport of ions and water and intestinal motility, and to inhibit serotonin transporter | Does not alter colonic transit time in IBS-C; may play a role in visceral nociception Urine melatonin metabolite lower in IBS patients than in controls, but does not differ between IBS-C and IBS-D | Mantovani et al. 2006; Lu et al. 2009; Radwan et al. 2009; Matheus et al. 2010; Wisniewska-Jarosinska et al. 2010 |

Abbreviations: CHO, carbohydrates; EC, enteroendocrine cells; GI, gastrointestinal; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; HPA, hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis; IBS-A, irritable bowel syndrome, alternating type; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea; ICC, interstitial cells of Cajal; MMCs, migrating motor complexes; PI-IBS, post-infection irritable bowel syndrome; PYY, peptide YY.

Gastrointestinal mucosal and faecal granins

Chromogranins or secretogranins are present in secretory vesicles of nervous, endocrine, immune and mast cells. Activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors in enteroendocrine cells induces the release of bioactive amines (e.g. serotonin, melatonin) or peptides. Chromogranin A (CgA) can induce the formation of mobile secretory granules and promote the sorting and release of peptide hormones from enteroendocrine cells (Montero-Hadjadje et al. 2009).

Compared with healthy controls, patients with IBS-D or alternating IBS (IBS-A) demonstrated higher levels of faecal CgA, secretogranin II (SgII) and SgIII, but lower levels of CgB. Faster colonic transit or lower colonic transit time were associated with higher faecal CgA, SgII and SgIII levels. Associations between the granins and symptoms were weak (Öhman et al. 2012). The elevation of faecal granins may serve as a marker for the involvement of endogenous transmitters that may be causing bowel dysfunction (Spiller et al. 2000). Duodenal CgA cell density is a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of IBS (El-Salhy, 2012), although increased faecal granins are not specific to IBS because they are also observed in lymphocytic colitis (El-Salhy et al. 2011) and coeliac disease (Pietroletti et al. 1986).

Serotonin and IBS

Serotonin (5-HT), a biogenic amine synthesized primarily in the GI tract, is stored in mucosal enterochromaffin cells (Spiller, 2001) and is released in response to mechanical and chemical stimulation. It exerts diverse effects through 22 receptor subtypes located on intrinsic and extrinsic nerves to regulate peristalsis, enhance secretion, and modulate sensory transmission between the gut and CNS. Mawe & Hofmann (2013) summarized the conventional functions of 5-HT as intrinsic reflexes (e.g. stimulation of propulsive and segmentation motility, epithelial secretion and vasodilation), and the activation of extrinsic vagal and spinal afferents that alter gastric emptying, pancreatic secretion, satiation, pain and discomfort and may mediate nausea and vomiting. Within the gut, 5-HT non-conventional actions include promoting inflammation, and developing and maintaining neurons and interstitial cells of Cajal.

Circulating serotonin

Circulating 5-HT is derived primarily from the gut and represents the 5-HT that does not undergo reuptake by the serotonin transporter (SERT) in the cells of the epithelial lining. Circulating postprandial 5-HT levels are increased in platelet-depleted plasma (PDP) in IBS-D (Houghton et al. 2003; Atkinson et al. 2006) and post-infection IBS (PI-IBS) (Dunlop et al. 2005), and are reduced (Dunlop et al. 2005) or unchanged (Atkinson et al. 2006) in IBS-C.

The elevated postprandial 5-HT in PDP in IBS-D, but not IBS-C, might reflect differences in platelet SERT uptake, which is disrupted in IBS-D (Bellini et al. 2003; Franke et al. 2010; Foley et al. 2011). This is supported by platelet 5-HT levels, which are reduced in IBS-D (Franke et al. 2010) and are approximately two-fold higher in IBS-C patients compared with healthy controls (Atkinson et al. 2006). Alternatively, release of 5-HT to physiological stimuli appears impaired in IBS-C (Atkinson et al. 2006).

Relationship of circulating 5-HT and colonic transit and sensation

In one study, a direct correlation between PDP 5-HT concentration and sigmoid colonic motility (phasic pressure) was found in a combined IBS-C (n = 17) and IBS-D (n = 18) cohort (Houghton et al. 2007). Consistent with this finding, another study, combining IBS-C and PI-IBS patients, reported a negative correlation between PDP 5-HT and colonic transit time (Dunlop et al. 2005), with the latter being generally inversely correlated with colonic phasic motility. 5-HT concentrations were significantly correlated with colonic pain and stool thresholds (Shekhar et al. 2013).

Mucosal 5-HT (or metabolites)

Findings of GI mucosal 5-HT content appear to differ according to the method of measurement: some studies have found elevated levels in IBS-C and functional constipation (Lincoln et al. 1990; Miwa et al. 2001; Zhao et al. 2002; Costedio et al. 2010), and others have found no statistically significant difference in intensity of serotonin immunoreactivity in any IBS group (El-Salhy et al. 2013, 2014).

Mucosal SLC6A4 (SERT or serotonin-transporter protein)

There is still controversy as to whether SERT protein expression is altered in patients with the various subtypes of IBS. A decrease in SERT expression in specimens from both IBS-D and IBS-C patients was first reported by Coates et al. (2004), although it was difficult to reconcile similar SERT expression in the two subgroups. Subsequently, other groups showed lower typtophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH-1) and SERT mRNA levels in the rectum in 23 IBS patients compared with controls (Kerckhoffs et al. 2012), decreased SERT expression in IBS-D in adults (Foley et al. 2011), and different SERT immunoreactivity intensity in IBS (whole group), IBS-D and IBS-C subjects in comparison with controls (El-Salhy et al. 2013). Other groups reported normal colonic mucosal expression of SERT in IBS-D and IBS-C (Camilleri et al. 2007) and chronic constipation (Lincoln et al. 1990; Costedio et al. 2010).

These mucosal content studies may be complicated by differences in 5-HTTLPR genotype in different IBS subgroups. Thus, patients with the L/L genotype demonstrated increased SERT mRNA and protein in colonic mucosa, compared with L/S and S/S patients (Wang et al. 2012).

GLP-1 and IBS

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is formed in ileal and colonic L-cells following post-translational processing from a proglucagon precursor molecule. Large amounts of GLP-1 are secreted into the bloodstream in response to intake of carbohydrates and fat. The main action of GLP-1 is nerve-dependent inhibition of GI motility through a relaxing effect mediated by afferent vagal fibres (Bucinskaite et al. 2009), as well as a nerve-mediated efferent response as shown in the rat (Tolessa et al. 1998).

In humans, GLP-1 inhibits gastric emptying and small intestinal migrating motor complexes (Hellström et al. 2008). The effects of GLP-1 have been evaluated in studies using the GLP-1 agonist, ROSE-010, which increased the proportion of IBS patients achieving pain relief with no safety issues other than nausea. ROSE-010 delayed gastric emptying, but did not retard colonic transit in patients with IBS-C (Camilleri et al. 2012).

Colorectal mucosal expression of other peptides in IBS

There is evidence of reduced expression of neuropeptide Y (Zhang et al. 2008) and peptide YY (El-Salhy et al. 2014), and increased expression of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (Zhang et al. 2008) and somatostatin (Han, 2013) in colonic mucosa of patients with IBS. The expression of somatostatin in mucosa is higher in IBS-C than IBS-D (El-Salhy et al. 2014). The functional significance of these changes in mucosal expression is unclear.

Central neurohormonal mechanisms in IBS

Hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis and stress in IBS

In some studies, the basal cortisol level (prior to an experimental visceral stressor) was found to be positively correlated with anxiety symptoms or early adverse life events, but not with IBS symptoms (Chang et al. 2009; Videlock et al. 2009). In another study, IBS-D patients exhibited substantially heightened cortisol levels at awakening (Suárez-Hitz et al. 2012).

Alterations in the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and autonomic activation have been documented in female IBS patients under baseline and acute laboratory and clinical stress conditions (Kudielka et al. 2004; Posserud et al. 2004; Elsenbruch et al. 2006; Mazur et al. 2007; Chang et al. 2009; FitzGerald et al. 2009; Heitkemper et al. 2012). For example, Chang et al. (2009) measured cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels over 24 h and documented that, during the day and around the time of morning awakening, plasma ACTH levels were significantly lower in IBS patients compared with a healthy control group. Heitkemper et al. (2012) reported that public speaking prior to bedtime increased cortisol, but not ACTH, levels in women with IBS. These examples suggest that HPA axis dysfunction results from prolonged stress (Kudielka et al. 2004; Chang et al. 2009).

However, findings of changes in plasma cortisol in IBS in response to stress are inconsistent across studies and have been reported as elevated (Chang et al. 2009), unchanged (Elsenbruch et al. 2006) or reduced (FitzGerald et al. 2009). Inconsistent findings may reflect differences in the degree and type of psychological distress, childhood trauma, perception and cognitive response to the different acute stress paradigms, duration of experimental stress, severity of IBS, presence of comorbidity, patient age and sleep quality (Burr et al. 2009; Videlock et al. 2009). HPA dysregulation may have biological effects, such as alteration of cognitive function on a hippocampally mediated test of visuospatial memory, which has been found to be related to cortisol levels and independent of psychiatric comorbidity in IBS patients (Kennedy et al. 2014).

Corticotrophin-releasing hormone stress and IBS

One potential mediator of the effects of stress and HPA response is corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) (Owens & Nemeroff, 1991). In animal models, stress activation of CRH receptors alters GI functions (Taché et al. 1993). CRH1 and CRH2 receptor subtypes have been cloned. In animals, stress-related changes in GI motility, such as delayed gastric emptying or accelerated colonic transit, can be blocked by a selective CRH1 receptor antagonist, antalarmin (Greenwood-Van Meerveld et al. 2005), and by the non-selective CRH receptor antagonist, α-helical CRH (Mönnikes et al. 1993).

In the brain and, possibly, the gut, CRH may be a molecular mediator of stress-induced exacerbation of IBS symptoms. For example, in humans, CRH evokes colonic motility and visceral perception, with exaggerated responses in IBS patients (Fukudo et al. 1998). In support of this finding, Sagami et al. (2004) showed improved colonic sensorimotor function and brain function in response to peptide CRH antagonists. These effects are mediated predominantly by type 2 CRH receptors because a more selective CRH1 antagonist, pexacerafont, did not significantly affect colonic transit in patients with IBS-D (Sweetser et al. 2009).

Administration of the non-selective α-helical CRH9–41 (10 μg kg−1) influenced human electroencephalographic (EEG) power spectra and topography at baseline and during colonic distension (Tayama et al. 2007): IBS patients showed a lower alpha power percentage and a higher beta power percentage in the EEG than normal controls at baseline, similar to findings in an earlier study (Fukudo et al. 1993).

The demonstration of potential effects of CRH-R1 mechanisms in anxiety, regional activation and effective connectivity of a stress-related emotional–arousal circuit during the expectation of abdominal pain suggests hyperactivation of CRH/CRH1 signalling in IBS pathophysiology (Hubbard et al. 2011). Recent data show upregulation of CRH-R1 signalling with expected abdominal pain (Labus et al. 2013).

Melatonin, a pineal and GI hormone, and IBS

Melatonin, the major secretory product of the pineal gland, is an indoleamine synthesized from tryptophan and secreted during the dark phase of the day; serotonin is its most direct precursor molecule. Large quantities of melatonin are also produced in enteroendocrine cells. Melatonin retards gastric emptying through effects on vagal afferents mediated at 5-HT3 and CCKB receptors (Kasimay et al. 2005). Melatonin also influences retardation of gastric emptying in response to ileal infusion of lipids (Teresa Martín et al. 2005). Although melatonin significantly retards colonic transit in healthy subjects, it does not alter colonic transit time in IBS-C (Lu et al. 2009). Melatonin may also play a role in visceral nociception (Mantovani et al. 2006). Melatonin is released locally in the intestine to modulate transmembrane transport of ions and water and intestinal motility, and inhibit serotonin transporter, enhancing the effects of 5-HT (Matheus et al. 2010).

Urinary excretion of a main melatonin metabolite, 6-sulphatoxymelatonin (6-SMLT), was lower in IBS patients than in controls, but did not differ between IBS-C and IBS-D patients (Radwan et al. 2009; Wisniewska-Jarosinska et al. 2010).

Autonomic nervous system

Autonomic function is discussed briefly, but is generally beyond the scope of the current article (Table 3).

Table 3.

Examples of altered central and autonomic neural functions in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

| Mechanisms | Observations in patients with IBS compared with healthy controls | References |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomic functions: baseline | Lower vagal tone in IBS overall than in controls while awake Lower vagal tone in IBS-C than controls and increased sympathetic activity in IBS-D group No differences in vagal function in childhood IBS No differences in any autonomic function test in adults with IBS | Smart & Atkinson, 1987; Heitkemper et al. 1998 Aggarwal et al. 1994 Jarrett et al. 2012 Camilleri et al. 2008 |

| Autonomic functions: during stimulation | Greater systolic BP response and diminished baroreceptor sensitivity to rectal or colonic distension in IBS patients Greater postprandial increases in plasma norepinephrine and systolic BP to nutrient load | Iovino et al. 1995; Spaziani et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2013 Elsenbruch et al. 2004 |

| Autonomic functions: during sleep | Elevated sympathovagal dominance during rapid eye movement sleep Lower vagal tone during sleep in IBS-C | Lee et al. 1998; Orr et al. 2000; Thompson et al. 2002 |

| HPA axis: basal | Increased basal plasma cortisol correlates with anxiety symptoms or early adverse life events, but not with IBS symptoms On awakening, higher cortisol in IBS-D, and lower ACTH in IBS | Chang et al. 2009; Videlock et al. 2009 Chang et al. 2009; Suárez-Hitz et al. 2012 |

| HPA axis: stress | Public speaking prior to bedtime increases cortisol, but not ACTH, in women with IBS Inconsistent findings of cortisol in response to stress in IBS may reflect differences in degree and type of psychological distress, childhood trauma, perception, severity of IBS, personality and cognitive response | Heitkemper et al. 2012 Elsenbruch et al. 2006; Burr et al. 2009; Chang et al. 2009; FitzGerald et al. 2009; Videlock et al. 2009 |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BP, blood pressure; HPA axis, hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea.

Baseline autonomic functions and associations with symptom phenotype

Autonomic function testing in patients during awake conditions and over a 24 h period showed lower vagal tone in IBS patients than in controls (Smart & Atkinson, 1987; Heitkemper et al. 1998).

There are differences in autonomic responses to stimuli (e.g. vasoconstrictor response to cold stress, postural adjustment ratio) among IBS-C and IBS-D patients: in one study, the IBS-D group demonstrated increased sympathetic activity, whereas the IBS-C subgroup showed diminished vagal tone compared with controls (Aggarwal et al. 1994). Other studies found no differences in vagal activity between young children with functional abdominal pain IBS and healthy young controls (Jarrett et al. 2012) or in 119 patients with IBS with different bowel function phenotypes (Camilleri et al. 2008).

Autonomic dysfunction during stimulation: visceral distension, stages of sleep and nutrient loading

Sympathetic nervous system activation modulates visceral perception, decreasing the threshold for discomfort secondary to duodenal distension. A greater systolic blood pressure response to rectal or colonic distension and associated diminished baroreceptor sensitivity in IBS patients suggest increased sympathetic and decreased vagal responsiveness (Iovino et al. 1995; Spaziani et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2013).

The stages of sleep serve as a model in which to detect autonomic differences. IBS patients have shown elevated sympathovagal dominance compared with healthy controls during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Orr et al. 2000). Vagal withdrawal during sleep in patients and controls was confirmed in IBS-C patients seeking medical help (Lee et al. 1998; Thompson et al. 2002). Other studies have shown autonomic hyper-responsiveness to nutrient load, which induces significantly greater postprandial increases in plasma norepinephrine and systolic blood pressure (Elsenbruch et al. 2004).

Conclusion

The neurohormonal control of the gut in IBS forms the basis for the most successful treatments of functional GI disorders (Camilleri, 2013); classical examples from the past are 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and 5-HT4 receptor agonists. The greatest unmet need is in the treatment of pain. It is anticipated that future management advances will be based on understanding of these neurohormonal mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Cindy Stanislav for secretarial assistance.

Glossary

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- CRH

corticotrophin-releasing hormone

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- GPBAR1

G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 1

- HPA axis

hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- IBS-A

irritable bowel syndrome, alternating type

- IBS-C

irritable bowel syndrome with constipation

- IBS-D

irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea

- PDP

platelet-depleted plasma

- PI-IBS

post-infection irritable bowel syndrome

- SCFAs

short chain fatty acids

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- 6-SMLT

6-sulphatoxymelatonin

- TPH-1

typtophan hydroxylase 1

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

Conceptualization of the review; review of the literature; authorship.

Funding

M.C. is supported by grants R01-DK67071 and R01-DK92179 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aerssens J, Camilleri M, Talloen W, Thielemans L, Göhlmann HW, van den Wyngaert I, Thielemans T, De Hoogt R, Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, Carlson PJ, Busciglio I, Burton DD, Smyrk T, Urrutia R, Coulie B. Alterations in mucosal immunity identified in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal A, Cutts TF, Abell TL, Cardoso S, Familoni B, Bremer J, Karas J. Predominant symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome correlate with specific autonomic nervous system abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemi F, Poole DP, Chiu J, Schoonjans K, Cattaruzza F, Grider JR, Bunnett NW, Corvera CU. The receptor TGR5 mediates the prokinetic actions of intestinal bile acids and is required for normal defecation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:145–154. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson W, Lockhart S, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B, Houghton LA. Altered 5-hydroxytryptamine signalling in patients with constipation- and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:34–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiroz F, Bouin M, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Poitras P, Serra J, Spiller RC. Mechanisms of hypersensitivity in IBS and functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(Suppl. 1):62–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bampton PA, Dinning PG, Kennedy ML, Lubowski DZ, Cook IJ. The proximal colonic motor response to rectal mechanical and chemical stimulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G443–G449. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00194.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini M, Rappelli L, Blandizzi C, Costa F, Stasi C, Colucci R, Giannaccini G, Marazziti D, Betti L, Baroni S, Mumolo MG, Marchi S, Del Tacca M. Platelet serotonin transporter in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome both before and after treatment with alosetron. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2705–2711. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P, Park AJ, Sinclair D, Khoshdel A, Lu J, Huang X, Deng Y, Blennerhassett PA, Fahnestock M, Moine D, Berger B, Huizinga JD, Kunze W, McLean PG, Bergonzelli GE, Collins SM, Verdu EF. The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut–brain communication. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behaviour and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucinskaite V, Tolessa T, Pedersen J, Rydqvist B, Zerihun L, Holst JJ, Hellström PM. Receptor-mediated activation of gastric vagal afferents by glucagon-like peptide-1 in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:978–e78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr RL, Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Jun SE, Heitkemper MM. Catecholamine and cortisol levels during sleep in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1148–e97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1626–1635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1207068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M. Pharmacological agents currently in clinical trials for disorders in neurogastroenterology. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4111–4120. doi: 10.1172/JCI70837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M, Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, Carlson PJ, Ferber I, Stephens D, Smyrk TC, Urrutia R, Aerssens J, Thielemans L, Göhlmann H, van den Wyngaert I, Coulie B. Alterations in expression of p11 and SERT in mucosal biopsy specimens of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:17–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M, Lasch K, Zhou W. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. The confluence of increased permeability, inflammation, and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G775–G785. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00155.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, Low PA, Sweetser S, Burton D, Baxter K, Ryks M, Zinsmeister AR. Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychological and autonomic functions in 119 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M, Vazquez-Roque M, Iturrino J, Boldingh A, Burton D, McKinzie S, Wong BS, Rao AS, Kenny E, Månsson M, Zinsmeister AR. Effect of a glucagon-like peptide 1 analog, ROSE-010, on GI motor functions in female patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G120–G128. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00076.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick VS, Gaginella TS, Carlson GL, Debongnie JC, Phillips SF, Hofmann AF. Effect of molecular structure on bile acid-induced alterations in absorptive function, permeability, and morphology in the perfused rabbit colon. J Lab Clin Med. 1979;94:661–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Sundaresh S, Elliott J, Anton PA, Baldi P, Licudine A, Mayer M, Vuong T, Hirano M, Naliboff BD, Ameen VZ, Mayer EA. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P, Shih W, Alberto M, Presson AP, Licudine A, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L. Autonomic response to a visceral stressor is dysregulated in irritable bowel syndrome and correlates with duration of disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e650–e659. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Rick GA. Distribution of myelinated nerves in ascending nerves and myenteric plexus of cat colon. Am J Anat. 1987;178:250–258. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001780306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, Sampson JE, Chen J, Blaszyk H, Crowell MD, Sharkey KA, Gershon MD, Mawe GM, Moses PL. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1657–1664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costedio MM, Coates MD, Brooks EM, Glass LM, Ganguly EK, Blaszyk H, Ciolino AL, Wood MJ, Strader D, Hyman NH, Moses PL, Mawe GM. Mucosal serotonin signalling is altered in chronic constipation but not in opiate-induced constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1173–1180. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop SP, Coleman NS, Blackshaw E, Perkins AC, Singh G, Marsden CA, Spiller RC. Abnormalities of 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–5163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, Hausken T. Abnormal rectal endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Regul Pept. 2014;188:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Gundersen TD. High chromogranin A cell density in the colon of patients with lymphocytic colitis. Mol Med Report. 2011;4:603–605. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Salhy M, Wendelbo I, Gundersen D. Serotonin and serotonin transporter in the rectum of patients with irritable bowel disease. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:451–455. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Holtmann G, Oezcan D, Lysson A, Janssen O, Goebel MU, Schedlowski M. Are there alterations of neuroendocrine and cellular immune responses to nutrients in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:703–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Lucas A, Holtmann G, Haag S, Gerken G, Riemenschneider N, Langhorst J, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Schedlowski M. Public speaking stress-induced neuroendocrine responses and circulating immune cell redistribution in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2300–2307. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré R, Tack J. Food and symptom generation in functional gastrointestinal disorders: physiological aspects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:698–706. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald LZ, Kehoe P, Sinha K. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation in women with irritable bowel syndrome in response to acute physical stress. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31:818–836. doi: 10.1177/0193945909339320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S, Garsed K, Singh G, Duroudier NP, Swan C, Hall IP, Zaitoun A, Bennett A, Marsden C, Holmes G, Walls A, Spiller RC. Impaired uptake of serotonin by platelets from patients with irritable bowel syndrome correlates with duodenal immune activation. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1434–1443. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke L, Schmidtmann M, Riedl A, van der Voort I, Uebelhack R, Mönnikes H. Serotonin transporter activity and serotonin concentration in platelets of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: effect of gender. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:389–398. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0167-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukudo S, Nomura T, Hongo M. Impact of corticotropin-releasing hormone on gastrointestinal motility and adrenocorticotropic hormone in normal controls and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1998;428:45–49. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukudo S, Nomura T, Muranaka M, Taguchi F. Brain–gut response to stress and cholinergic stimulation in irritable bowel syndrome. A preliminary study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:133–141. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Tatewaki M, Yamada T, Fujimiya M, Mantyh C, Voss M, Eubanks S, Harris M, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate colonic transit via intraluminal 5-HT release in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1269–R1276. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00442.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart GF. Pathobiology of visceral pain: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Visceral afferent contributions to the pathobiology of visceral pain. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G834–G838. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.6.G834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Johnson AC, Cochrane S, Schulkin J, Myers DA. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 receptor-mediated mechanisms inhibit colonic hypersensitivity in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B. Correlation between gastrointestinal hormones and anxiety-depressive states in irritable bowel syndrome. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:715–720. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper M, Burr RL, Jarrett M, Hertig V, Lustyk MK, Bond EF. Evidence for autonomic nervous system imbalance in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2093–2098. doi: 10.1023/a:1018871617483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper MM, Cain KC, Deechakawan W, Poppe A, Jun SE, Burr RL, Jarrett ME. Anticipation of public speaking and sleep and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström PM, Näslund E, Edholm T, Schmidt PT, Kristensen J, Theodorsson E, Holst JJ, Efendic S. GLP-1 suppresses gastrointestinal motility and inhibits the migrating motor complex in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton LA, Atkinson W, Lockhart S, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B. Sigmoid-colonic motility in health and irritable bowel syndrome: a role for 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton LA, Atkinson W, Whitaker RP, Whorwell PJ, Rimmer MJ. Increased platelet depleted plasma 5-hydroxytryptamine concentration following meal ingestion in symptomatic female subjects with diarrhoea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:663–670. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard CS, Labus JS, Bueller J, Stains J, Suyenobu B, Dukes GE, Kelleher DL, Tillisch K, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 antagonist alters regional activation and effective connectivity in an emotional–arousal circuit during expectation of abdominal pain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12491–12500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovino P, Azpiroz F, Domingo E, Malagelada J. The sympathetic nervous system modulates perception and reflex responses to gut distension in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:680–686. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Czyzewski D, Zeltzer L, Shulman RJ. Autonomic nervous system function in young children with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome. J Pain. 2012;13:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasimay O, Cakir B, Devseren E, Yegen BC. Exogenous melatonin delays gastric emptying rate in rats: role of CCK2 and 5-HT3 receptors. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56:543–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PJ, Clarke G, O'Neill A, Groeger JA, Quigley EM, Shanahan F, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Cognitive performance in irritable bowel syndrome: evidence of a stress-related impairment in visuospatial memory. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1553–1566. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoffs AP, ter Linde JJ, Akkermans LM, Samsom M. SERT and TPH-1 mRNA expression are reduced in irritable bowel syndrome patients regardless of visceral sensitivity state in large intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1053–G1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00153.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin P, Zinsmeister A, Phillips S. Motor responses to food of the ileum, proximal colon, and distal colon of healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:762–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreulen DL, Szurszewski JH. Reflex pathways in the abdominal prevertebral ganglia: evidence for a colo-colonic inhibitory reflex. J Physiol. 1979;295:21–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:83–98. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labus JS, Dinov ID, Jiang Z, Ashe-McNalley C, Zamanyan A, Shi Y, Hong JY, Gupta A, Tillisch K, Ebrat B, Hobel S, Gutman BA, Joshi S, Thompson PM, Toga AW, Mayer EA. Irritable bowel syndrome in female patients is associated with alterations in structural brain networks. Pain. 2014;155:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labus JS, Hubbard CS, Bueller J, Ebrat B, Tillisch K, Chen M, Stains J, Dukes GE, Kelleher DL, Naliboff BD, Fanselow M, Mayer EA. Impaired emotional learning and involvement of the corticotropin-releasing factor signalling system in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1253–1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson MB, Tillisch K, Craig AD, Engström M, Labus J, Naliboff B, Lundberg P, Ström M, Mayer EA, Walter SA. Brain responses to visceral stimuli reflect visceral sensitivity thresholds in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:463–472.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CT, Chuang TY, Lu CL, Chen CY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Abnormal vagal cholinergic function and psychological behaviors in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a hospital-based Oriental study. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1794–1799. doi: 10.1023/a:1018848122993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln JR, Crowe MA, Kamm MA, Burnstock G, Lennard-Jones JE. Serotonin and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid are increased in the sigmoid colon in severe idiopathic constipation. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu WZ, Song GH, Gwee KA, Ho KY. The effects of melatonin on colonic transit time in normal controls and IBS patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1087–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0463-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani M, Kaster MP, Pertile R, Calixto JB, Rodrigues AL, Santos AR. Mechanisms involved in the antinociception caused by melatonin in mice. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheus N, Mendoza C, Iceta R, Mesonero JE, Alcalde AI. Melatonin inhibits serotonin transporter activity in intestinal epithelial cells. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawe GM, Hoffman JM. Serotonin signalling in the gut – functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:473–486. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA. Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1692–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Tillisch K. The brain–gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Ann Rev Med. 2011;62:381–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012309-103958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur M, Furgala A, Jablonski K, Madroszkiewicz D, Ciećko-Michalska I, Bugajski A, Thor PJ. Dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system activity is responsible for gastric myoelectric disturbances in the irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58:131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa J, Echizen H, Matsueda K, Umeda N. Patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome may have elevated serotonin concentrations in colonic mucosa as compared with diarrhoea-predominant patients and subjects with normal bowel habit. Digestion. 2001;63:188–194. doi: 10.1159/000051888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollen RMHG, Salvioli B, Camilleri M, Burton D, Kost LJ, Phillips SF, Pemberton JH. The effects of biofeedback on rectal sensation and distal colonic motility in patients with disorders of rectal evacuation: evidence of an inhibitory rectocolonic reflex in humans? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:751–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mönnikes H. Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(Suppl. 1):S98–S101. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31821fbf44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mönnikes H, Schmidt BG, Tache Y. Psychological stress-induced accelerated colonic transit in rats involves hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing factor. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:716–723. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Hadjadje M, Elias S, Chevalier L, Benard M, Tanguy Y, Turquier V, Galas L, Yon L, Malagon MM, Driouich A, Gasman S, Anouar Y. Chromogranin A promotes peptide hormone sorting to mobile granules in constitutively and regulated secreting cells: role of conserved N- and C-terminal peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12420–12431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Nadelhaft I, deGroat WC. The distribution within the spinal cord of visceral primary afferent axons carried by the lumbar colonic nerve of the cat. Brain Res. 1986;398:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman L, Simrén M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman L, Stridsberg M, Isaksson S, Jerlstad P, Simrén M. Altered levels of fecal chromogranins and secretogranins in IBS: relevance for pathophysiology and symptoms? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:440–447. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr WC, Elsenbruch S, Harnish MJ. Autonomic regulation of cardiac function during sleep in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;98:2865–2871. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin releasing factor. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:425–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietroletti R, Bishop AE, Carlei F, Bonamico M, Lloyd RV, Wilson BS, Ceccamea A, Lezoche E, Speranza V, Polak JM. Gut endocrine cell population in coeliac disease estimated by immunocytochemistry using a monoclonal antibody to chromogranin. Gut. 1986;27:838–843. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.7.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posserud I, Agerforz P, Ekman R, Bjornsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered visceral perceptual and neuroendocrine response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome during mental stress. Gut. 2004;53:1102–1108. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.017962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan P, Skrzydlo-Radomanska B, Radwan-Kwiatek K, Burak-Czapiuk B, Strzemecka J. Is melatonin involved in the irritable bowel syndrome? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain–gut–enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:306–314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. I. Bitter taste receptors and α-gustducin in the mammalian gut. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G171–G177. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00073.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagami Y, Shimada Y, Tayama J, Nomura T, Satake M, Endo Y, Shoji T, Karahashi K, Hongo M, Fukudo S. Effect of a corticotropin releasing hormone receptor antagonist on colonic sensory and motor function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:958–964. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar C, Monaghan PJ, Morris J, Issa B, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B, Houghton LA. Rome III functional constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation are similar disorders within a spectrum of sensitization, regulated by serotonin. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:749–757. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.014. quiz e13–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart HL, Atkinson M. Abnormal vagal function in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1987;2:475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91792-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaziani R, Bayati A, Redmond K, Bajaj H, Mazzadi S, Bienenstock J, Collins SM, Kamath MV. Vagal dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome assessed by rectal distension and baroreceptor sensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller RC. Effects of serotonin on intestinal secretion and motility. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2001;17:99–103. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1662–1671. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornley JP, Hebden JM, Wright T, Skinner M, Neal KR. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47:804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen AM, Haddad AC, Phillips SF. Passage of carbohydrate into the colon. Direct measurements in humans. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Hitz KA, Otto B, Bidlingmaier M, Schwizer W, Fried M, Ehlert U. Altered psychobiological responsiveness in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:221–231. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244fb82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser S, Camilleri M, Linker Nord SJ, Burton DD, Castenada L, Croop R, Tong G, Dockens R, Zinsmeister AR. Do corticotropin releasing factor-1 receptors influence colonic transit and bowel function in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1299–G1306. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00011.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tache Y, Mönnikes H, Bonaz B, Rivier J. Role of CRF in stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;697:233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayama J, Sagami Y, Shimada Y, Hongo M, Fukudo S. Effect of alpha-helical CRH on quantitative electroencephalogram in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:471–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teresa Martín M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Melatonin as a modulator of the ileal brake mechanism. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:559–563. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JJ, Elsenbruch S, Harnish MJ, Orr WC. Autonomic functioning during REM sleep differentiates IBS symptom subgroups. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3147–3153. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Guyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1394–1401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolessa T, Gutniak M, Holst JJ, Efendic S, Hellström PM. Glucagon-like peptide-1 retards gastric emptying and small bowel transit in the rat: effect mediated through central or enteric nervous mechanisms. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2284–2290. doi: 10.1023/a:1026678925120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treem WR, Ahsan N, Kastoff G, Hyams JS. Fecal short-chain fatty acids in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: in vitro studies of carbohydrate fermentation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23:280–286. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199610000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videlock EJ, Adeyemo M, Licudine A, Hirano M, Ohning G, Mayer M, Mayer EA, Chang L. Childhood trauma is associated with hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis responsiveness in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1954–1962. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Chang Y, Chang YY, Cheng J, Li J, Wang T, Zhang QY, Liang DC, Sun B, Wang BM. Serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphisms and serotonin transporter expression in the colonic mucosa of irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewska-Jarosinska M, Chojnacki J, Konturek S, Brzozowski T, Smigielski J, Chojnacki C. Evaluation of urinary 6-hydroxymelatonin sulphate excretion in women at different age with irritable bowel syndrome. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yan Y, Shi R, Lin Z, Wang M, Lin L. Correlation of gut hormones with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2008;78:72–76. doi: 10.1159/000165352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao RH, Baig MK, Mack J, Abramson S, Woodhouse S, Wexner SD. Altered serotonin immunoreactivities in the left colon of patients with colonic inertia. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:56–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Verne GN. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity – clinical implications in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:349–355. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]