Abstract

The IRG system of IFNγ-inducible GTPases constitutes a powerful resistance mechanism in mice against Toxoplasma gondii and two Chlamydia strains but not against many other bacteria and protozoa. Why only T. gondii and Chlamydia? We hypothesized that unusual features of the entry mechanisms and intracellular replicative niches of these two organisms, neither of which resembles a phagosome, might hint at a common principle. We examined another unicellular parasitic organism of mammals, member of an early-diverging group of Fungi, that bypasses the phagocytic mechanism when it enters the host cell: the microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Consistent with the known susceptibility of IFNγ-deficient mice to E. cuniculi infection, we found that IFNγ treatment suppresses meront development and spore formation in mouse fibroblasts in vitro, and that this effect is mediated by IRG proteins. The process resembles that previously described in T. gondii and Chlamydia resistance. Effector (GKS subfamily) IRG proteins accumulate at the parasitophorous vacuole of E. cuniculi and the meronts are eliminated. The suppression of E. cuniculi growth by IFNγ is completely reversed in cells lacking regulatory (GMS subfamily) IRG proteins, cells that effectively lack all IRG function. In addition IFNγ-induced cells infected with E. cuniculi die by necrosis as previously shown for IFNγ-induced cells resisting T. gondii infection. Thus the IRG resistance system provides cell-autonomous immunity to specific parasites from three kingdoms of life: protozoa, bacteria and fungi. The phylogenetic divergence of the three organisms whose vacuoles are now known to be involved in IRG-mediated immunity and the non-phagosomal character of the vacuoles themselves strongly suggests that the IRG system is triggered not by the presence of specific parasite components but rather by absence of specific host components on the vacuolar membrane.

Author Summary

For some time we have studied an intracellular resistance system essential for mice to survive infection with the intracellular protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, that is based on a family of proteins, immunity-related GTPases or IRG proteins. Immediately after the parasite enters a cell, IRG proteins accumulate on the membrane of the vacuole in which the organism resides. Within a few hours the vacuole membrane breaks down and the parasite dies. A puzzle is why this mechanism works on Toxoplasma, but only on one other organism among the many tested, namely the bacterial species, Chlamydia. What do these widely different parasites have in common that so many other bacteria and protozoa lack? Neither Toxoplasma nor Chlamydia is taken up by conventional phagocytosis. In this paper we suggest that this is an important clue by showing that a microsporidian, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, a highly-divergent fungal parasite, which also invades cells bypassing phagocytosis, is resisted by the IRG system. Therefore, we propose here the “missing self” principle: IRG proteins bind to vacuolar membranes only in the absence of a host derived inhibitor that is present on phagosomal membranes but excluded from the plasma membrane invaginated by IRG target organisms during non-phagosomal entry.

Introduction

The IFNγ-inducible, immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) are a family of proteins essential for innate resistance of mice against certain intracellular pathogens. Until now, the protozoon Toxoplasma gondii [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] and its very close relative, Neospora caninum [6], [7], as well as two strains of the bacterium Chlamydia [8], [9], [10], [11], [12] have been shown to be controlled by the IRG system. However, the IRG resistance system does not engage many other highly diverse organisms, including Salmonella, Listeria, Mycobacteria, Trypanosoma, Rhodococcus or Plasmodium, and the murine-specific strain of Chlamydia [reviewed in [13]].

From extended work in the Toxoplasma system, we and others have demonstrated that effector IRG proteins such as Irga6, Irgb6, Irgb10, Irgb2-b1 and Irgd relocalise from their cytosolic compartments to the cytosolic face of the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM) [4], [14], [15] in a GTP-dependent [16], [17] and cooperative manner [18]. In electron microscopy images, the PVM appears ruffled and vesiculated [3], [4], [19]. It is proposed that this action reduces the effective surface-to-volume ratio, putting the PVM under tension against the elastic cytoskeleton of the parasite and leading ultimately to its rupture [13]. Once exposed to the cytosol the parasite dies for unexplained reasons [3], [4], [20].

IRG proteins can be divided into the effector GKS subfamily, including the IRGA and IRGB proteins and Irgd (all carrying a canonical GxxxxGKS motif in the P-loop of the GTP-binding site) and the regulatory GMS subfamily, namely Irgm1, Irgm2 and Irgm3 (with a non-canonical GxxxxGMS motif) [21], [22]. GMS proteins populate the vacuoles of T. gondii or inclusions of Chlamydia either not at all (Irgm1) or only to a limited extent (Irgm2, Irgm3) [1], [4], [18], [23]; their function is to inhibit inappropriate GTP-dependent activation of the GKS proteins on host vesicular compartments in IFNγ-induced cells before the parasite enters [16].

It is not known why the action of IRG proteins is restricted to so few and so dissimilar parasitic organisms. We hypothesized that unusual features of the intracellular replicative niches of T. gondii and Chlamydia strains, neither of which resembles a phagosome, might hint at a common principle. To test this hypothesis we decided to examine cell-autonomous resistance in vitro to the microsporidian, Encephalitozoon cuniculi. The Microsporidia, recently re-classified as the earliest divergent group of the Fungi [24], [25], are abundant, obligate intracellular eukaryotic parasites of many diverse animal groups including mammals. E. cuniculi is a convenient representative since it is easily cultivated in vitro and its genome is fully sequenced, which is at 2.9 Mb one of the smallest known eukaryotic genomes [26]. E. cuniculi and its relatives E. hellem and E. intestinalis are common opportunistic pathogens for immunocompromised humans [27].

Microsporidia, including E. cuniculi, have a peculiar entry mechanism into host cells utterly unlike conventional phagocytosis. The thick-walled unicellular spore of E. cuniculi contains the organism itself (the sporoplasm) and a coiled proteinaceous tube, the polar tube, which can be suddenly extruded as a result of an osmotic stimulus and pushes a deep and narrow invagination in any adjacent host cell plasma membrane. The sporoplasm is then expelled through the polar tube and can be found deep in the host cytoplasm in an intracellular parasitophorous vacuole bounded by a membrane mainly derived from the host plasma membrane [reviewed in [28]]. The intracellular sporoplasm, now termed meront, divides repeatedly in its vacuole and eventually differentiates into large numbers of spores, finally lysing the host cell to release the mature environmentally-resistant spores [29]. By virtue of its remarkable non-phagocytic entry mechanism, this natural parasite of rodents and rabbits was an interesting potential target for the IRG resistance system, and it has been reported that IFNγ induces strong cell-autonomous immunity against this organism [30], [31], [32].

In the present study we show that the IRG system is indeed required for cell-autonomous resistance to E. cuniculi. We confirm the development of resistance following IFNγ treatment of fibroblasts and show that several IRG proteins localise to the PVM of intracellular E. cuniculi. Moreover, E. cuniculi infection triggered IFNγ-dependent reactive cell death, as seen earlier in T. gondii resistance [20]. To demonstrate the importance of IRG proteins in IFNγ-dependent growth restriction of E. cuniculi, we show that IFNγ-mediated resistance was completely lost in mouse cells that are deficient in the regulatory GMS proteins, Irgm1 and Irgm3, a double deficiency that inactivates the whole IRG system.

The phylogenetic range of the three classes of target organism of the IRG resistance system - bacteria, a fungus and protozoa - and their vastly dissimilar biology, strongly suggests that the specificity with which IRG proteins localise to parasitophorous vacuoles relates to a common characteristic of the host-derived membrane of such vacuoles rather than to a common ligand derived from the parasites themselves.

Results

IFNγ restricts E. cuniculi growth in primary mouse fibroblasts

It was first reported in 1995 that IFNγ induction restricts microsporidial growth in mammalian cells in vitro using E. cuniculi infection of murine peritoneal macrophages [30]. Subsequent studies confirmed the suppressive effect of IFNγ on E. cuniculi growth as well as on E. intestinalis using murine peritoneal macrophages [31], [32], the murine enterocyte cell line CMT-93 and human enterocyte cell line Caco-2 [33] as well as primary human monocyte-derived macrophages [34]. Furthermore, IFNγ-deficient mice are susceptible to E. cuniculi and E. intestinalis infection [32], [35], [36], [37]. It is characteristic of the IRG resistance system that it is efficient in non-myeloid cells such as fibroblasts [1], [4], [38]. We therefore tested IFNγ-dependence of cell-autonomous resistance against E. cuniculi in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. IFNγ-induced and uninduced C57BL/6 mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) monolayers were infected with E. cuniculi spores and the replication of the parasites followed by immunofluorescence microscopy and Western Blot analysis. E. cuniculi was detected with an antibody directed against a cytoplasmic protein (mAB 6G2) of the earliest infectious stages (meronts), or an antiserum against the spore wall protein 1 (pAS anti-SWP1), which is synthesized later in infection [39].

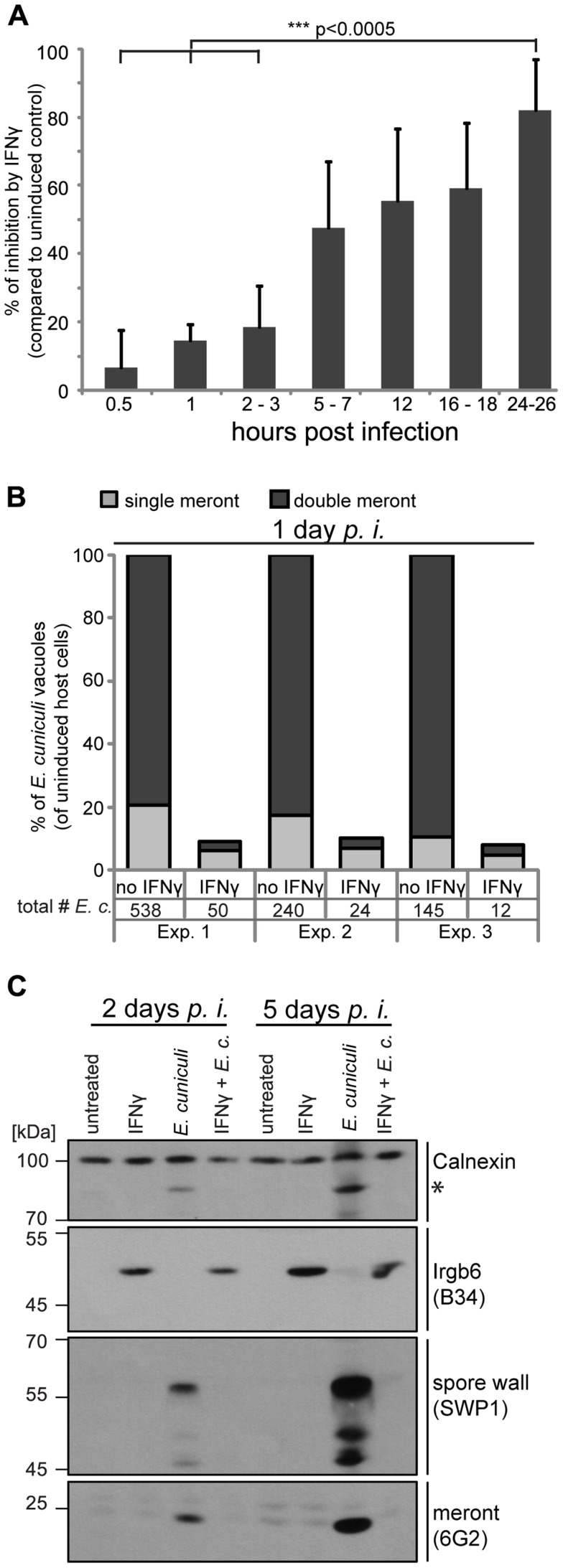

A time series of 0.5 to 24 hours post infection showed continuous IFNγ-dependent loss of E. cuniculi meronts (determined by counting of 6G2-positive meronts per host nuclei). Meront numbers at the earliest time point measured (0.5 hours) were equivalent in IFNγ-treated and untreated cells showing that E. cuniculi invasion into the host cells was not significantly affected by prior IFNγ induction (Figure 1A). Next, we quantified not only single meronts, but also meronts that had replicated by binary fission (double meronts) and compared uninduced to IFNγ-induced MEF cells 24 hours post infection. Of the few surviving meronts at 24 h, very few had successfully divided in IFNγ-induced cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. IFNγ restricts E. cuniculi growth in mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

(A) Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from C57BL/6 mice were induced with IFNγ for 24 h or left uninduced before infection with E. cuniculi spores. Cells were fixed at the indicated time points and the number of meronts (stained with anti-meront mAb 6G2) per 500 host nuclei (stained with DAPI) was counted. The inhibition in the IFNγ-treated sample compared to the uninduced control sample is presented as mean +/− standard deviation (SD) of 3–7 replicates per time point from at least 2 individual experiments. Significant differences (of 0.5 h, 1 h and 2–3 h compared to 24–26 h) were calculated with a two tailed T-test. (B) MEFs were induced with IFNγ or left uninduced, infected with E. cuniculi spores for 24 h and stained as in A. Single meronts and meronts that divided once (double meront) were counted per 500 host nuclei and shown as percent of total vacuoles of uninduced controls. Numbers indicate the counted number of single or double meronts per 500 host cells. Data from three independent experiments (Exp. 1–3) is presented. (C) MEFs were stimulated with IFNγ and/or infected with E. cuniculi spores for 2 or 5 days or left untreated. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western Blots were cut into three regions to probe for anti-meront mAB 6G2 as well as anti-spore wall protein 1 pAS SWP1. Calnexin staining served as loading control and Irgb6 staining (mAB B34) to proof IFNγ-induction. The asterisk marks an unknown E. cuniculi-derived protein that is detected by the Calnexin antibody. These Western Blots emerged from one single SDS-PAGE, the 45–70 kDa region was first probed with mouse mAB B34, stripped, and then probed for anti-SWP1 rabbit pAS. Experiments for both time points were performed at least three times.

In addition, Western Blot analysis of whole cell lysates from infected MEF cells showed that meront development as well as the formation of new spores was blocked by IFNγ (Figure 1C). In uninduced MEF cells, E. cuniculi-dependent protein bands were detected with the meront-specific antibody, indicative of replication, and with the spore-specific antiserum, indicative of maturation at 2 days post infection. The intensity of these parasite-specific bands further increased at 5 days post infection. In contrast, these bands could not be detected in E. cuniculi-infected IFNγ-induced cells either 2 or 5 days after infection. Taken together, IFNγ kills meronts, inhibits meront replication, and blocks spore formation of E. cuniculi in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

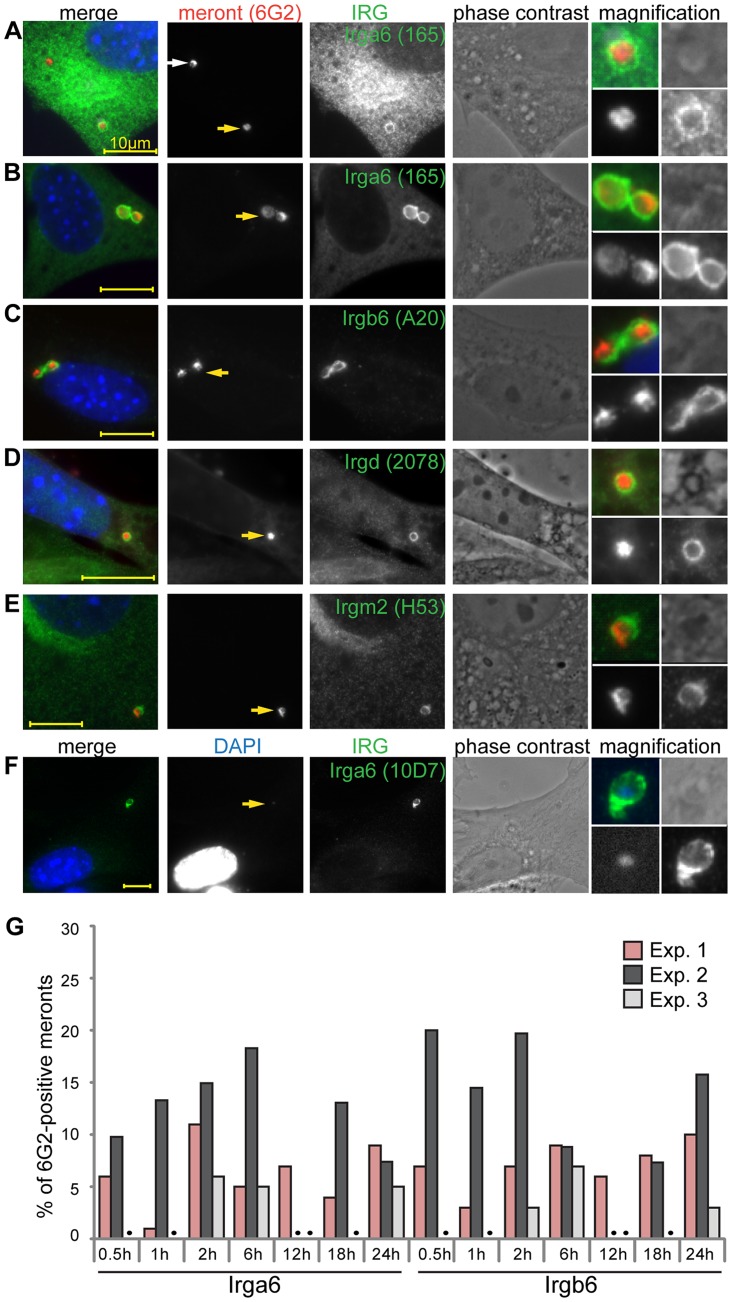

IRG proteins accumulate on the PVM of E. cuniculi

When T. gondii infects IFNγ-treated mouse fibroblasts, the induced IRG proteins, especially the effector GKS proteins, accumulate on the PVM and lead to disruption of the vacuole [20]. To examine whether similar IRG-related processes might also occur on the microsporidian vacuole, we co-stained IFNγ-treated, E. cuniculi-infected, MEF cells with immunological reagents against individual GKS effector proteins (Irga6, Irgb6 and Irgd) as well against the GMS regulator proteins (Irgm1 and Irgm2) 24 h post infection (Figure 2). Some meronts were indeed coated with IRG proteins, but most were IRG-negative. Both Irga6-coated and uncoated vacuoles were found together in multiply infected host cells (Figure 2A). Irga6 and Irgb6 were found on vacuoles at higher frequencies, while Irgd and Irgm2 were found at lower but consistent frequencies (below 5%) (Figure 2B–E). Irgm1 was never found at the E. cuniculi PVM (more than 1000 meronts in three independent experiments were analysed). In IFNγ-induced cells, cytoplasmic Irga6 is predominantly in the GDP-bound form, but accumulates on the T. gondii PVM in the GTP-bound activated form, which can be specifically detected with the mouse antibody10D7 [17]. Because we could not conduct a co-staining with the mouse anti-meront antibody, 6G2, in combination with 10D7, we identified the meront via its enhanced DAPI signal to show that indeed Irga6 was accumulating on E. cuniculi vacuoles in the GTP-bound state (Figure 2F) as in T. gondii immunity. The number of vacuoles positive for Irga6 or Irgb6 was examined in more detail at different time points after infection (Figure 2G). The frequency of Irga6- and Irgb6-positive vacuoles varied between experiments (1–20%), but did not significantly increase or decrease between 0.5–24 hours post infection (Figure 2G) as the number of meronts progressively dropped, suggesting relatively fast clearance of the IRG-positive vacuoles.

Figure 2. IRG proteins accumulate at the E. cuniculi parasitophorous vacuolar membrane.

(A–F) MEFs were induced with IFNγ for 24 h and then infected with E. cuniculi spores for 24 h. Fixed cells were stained for anti-meront mAB 6G2 as well as for endogenous Irga6 (165/3 pAS and 10D7 mAB), Irgb6 (A20 pAB), Irgd (2078 pAS) and Irgm2 (H53 pAS). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Representative microscopic images of IRG-positive E. cuniculi PVMs are presented. Yellow arrows point at the IRG-loaded PVM which is magnified at the end of each panel (zoom in the following order: upper left: merged image, upper right: phase contrast, lower left: anti-meront, lower right anti-IRG); white arrow: unloaded meront, every scale bar is 10 µm. (G) Quantification of Irga6 and Irgb6 loading onto the E. cuniculi PVM at different time points post infection. 100 vacuoles were evaluated per sample, a black dot indicates that sample was not counted, three independent experiments are shown.

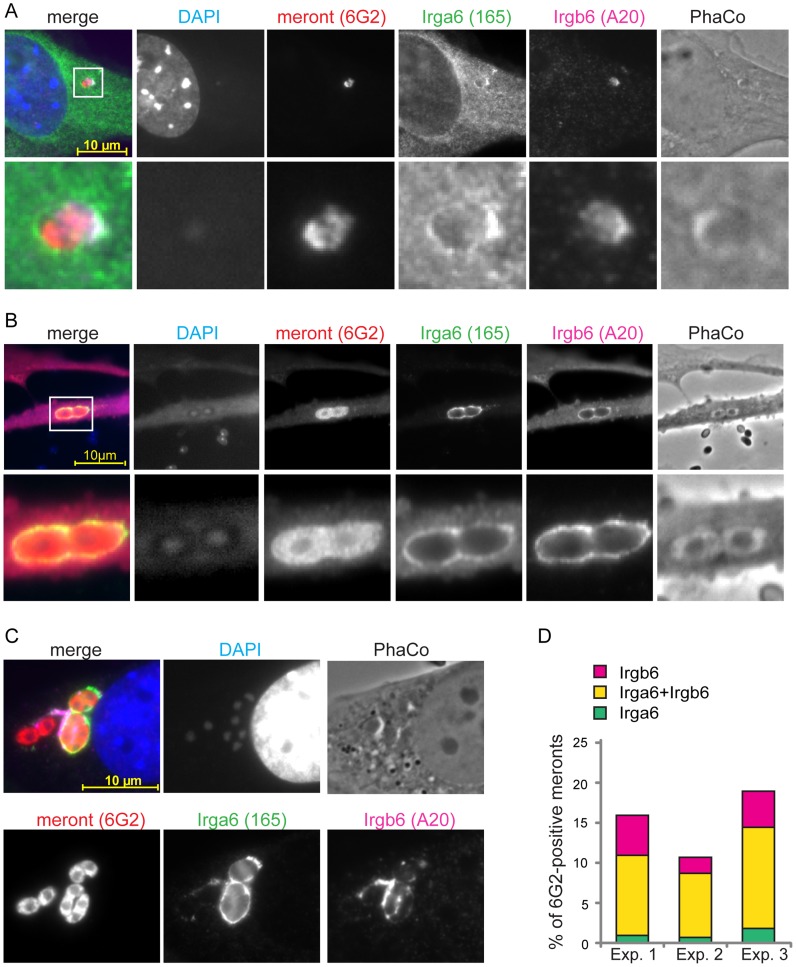

IRG proteins load onto PVM of E. cuniculi in a cooperative manner

A detailed view of IRG loading onto the T. gondii PVM has been established. IRG proteins accumulate on the PVM in a hierarchical order with Irgb6, Irgb10 and Irga6 as pioneers and demonstrate cooperative behaviour by stabilizing each other at the PVM [18]. In order to investigate cooperative loading on the E. cuniculi PVM, we conducted triple immunofluorescent stainings to identify the meront and two GKS proteins, Irga6 and Irgb6. Individual vacuoles positive for both IRG proteins were observed at early and late time points, such as 12 h post infection (Figure 3A) and 24 h post infection (Figure 3B, C). In most cases, Irga6 and Irgb6 co-localised to single vacuoles (Figure 3B), although often without accurate spatial coincidence on the PVM (Figure 3C). Notably, the number of E. cuniculi vacuoles accumulating both IRG proteins was higher than single-coated ones (Figure 3D). In view of the low frequencies of accumulation of individual IRG proteins, it is clear that the frequency of double-loaded vacuoles is highly non-random, suggesting that loading is cooperative between different IRG proteins, as seen on the T. gondii PVM.

Figure 3. IRG proteins load onto PVM in a cooperative manner.

MEFs were induced with IFNγ for 24 h and then infected with E. cuniculi spores for 12 h (A) or 24 h (B, C). Fixed cells were stained for meronts (mouse mAB 6G2, red) as well as for endogenous Irga6 (rabbit pAS165/3, green) and Irgb6 (goat pAB A20, far-red pseudocolored in magenta). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Representative images from 4 independent experiments are shown; white box indicates enlarged area shown below; scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Quantification of cooperative loading after 24 h; Irgb6-single, Irga6-single or Irgb6/Irga6-double (both) positive meronts are shown as % of total 6G2-positive meronts; 100 vacuoles were counted in each independent experiment (Exp. 1–3).

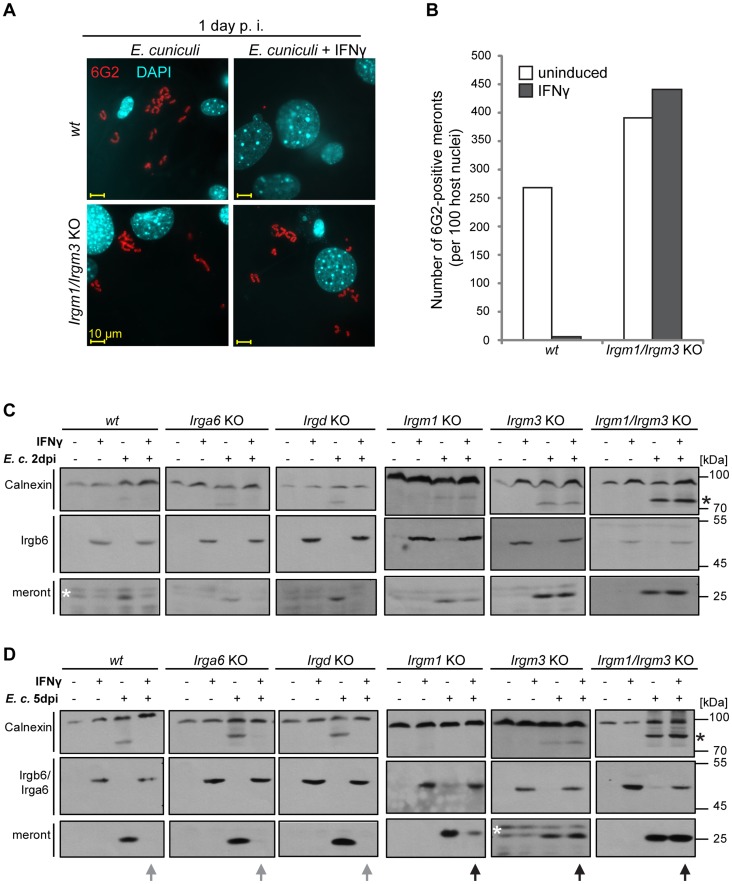

IFNγ-mediated inhibitory effects on E. cuniculi are lost in GMS-deficient cells

To assess the importance of IRG proteins in the IFNγ-dependent restriction of E. cuniculi, we investigated the development of the parasite in cells derived from IRG knock-out mice. First, we examined E. cuniculi infection in IFNγ-induced primary wildtype and Irgm1/Irgm3 −/− MEF cells, which lack the two regulator GMS proteins, Irgm1 and Irgm3, and also express reduced levels of GKS proteins [40]. The number of meronts observed in Irgm1/Irgm3 −/− MEF cells 24 h after infection was the same whether the cells were induced with IFNγ or not (Figure 4A, B). In contrast, and as observed in Figure 1, the number of meronts in IFNγ-induced wildtype cells was drastically reduced at 24 h after infection compared with uninduced controls (Figure 4A, B).

Figure 4. IFNγ suppressive effect on E. cuniculi growth is impaired in GMS-IRG knock-out cells.

(A) Wildtype (wt) or Irgm1/Irgm3 knock-out (KO) MEFs were induced with 200 U/ml IFNγ for 24 h and then infected with E. cuniculi spores for 24 h or left untreated. Cells were fixed and stained for meronts using 6G2 mAB (red) and host nuclei with DAPI (pseudocolored in cyan). Representative fluorescence microscopic images are shown. (B) Quantification of A, representative of two independent experiments. (C/D) Transformed wildtype or transformed IRG knock-out MEFs were induced with IFNγ for 24 h and then infected with E. cuniculi spores or left untreated. Cells were harvested after 2 days (in D) and 5 days (in E) post-infection. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western blots were cut into three regions and simultaneously probed for anti-meront mAB 6G2, anti-Calnexin pAB, which served as loading control and anti-Irgb6 (mAB B34) or anti-Irga6 (mAB 10E7 for Irgm1 KO and Irgm3 KO MEFs both at 5 d post infection; 165/3 pAS for Irgm1/Irgm3KO MEFs at 5 d post infection) as IFNγ-induction control. The black arrows highlight a 6G2-positive protein band indicating E. cuniculi growth despite presence of IFNγ, which is inhibited in wt cells (grew arrows). The asterisk marks an unknown E. cuniculi-derived protein that is detected by the Calnexin antibody. The white asterisk marks unspecific bands. The four samples of one cell line per time point were analyzed together by one single SDS-PAGE and Western Blot, except for the Irgm1KO MEFs at 2 d post infection. The data represents at least three independent experiments.

We next assayed IFNγ-inducible resistance to E. cuniculi in transformed fibroblasts from mice deficient in single IRG genes as well as in the Irgm1/Irgm3 −/− double knock-out cells. Parasite growth was assessed with the anti-meront antibody by Western blot, while the expression of Irgb6 (or Irga6) confirmed successful IFNγ induction (Figure 4C–D). In wildtype cells, IFNγ-induction resulted in complete loss of the meront marker at 2 and 5 days after infection, while in the Irgm1/Irgm3 −/− double knock-out cells IFNγ-induction caused no inhibition of meront growth. Single mutants for either Irga6 or Irgd, two members of the GKS effector subfamily, showed no loss of resistance relative to wildtype cells. However, cells lacking one GMS protein, Irgm1 or Irgm3, both showed clear susceptibility phenotypes. Susceptibility of the Irgm1-deficient cells was incomplete, while Irgm3-deficient cells were apparently as susceptible as Irgm1/Irgm3 double-deficient cells. Interestingly, Irgm3 deficiency also has a stronger susceptibility phenotype than Irgm1 deficiency for T. gondii in IFNγ-induced MEFs (unpublished observations). The stronger phenotype from the GMS knock-outs is expected, because these deficiencies deregulate all the GKS effectors [41]. The undetectable effects of the two GKS effector knock-outs is consistent with the much weaker in vivo phenotypes of single Irga6 and Irgd deficiencies in T. gondii infection [2], [42]. A deficiency of several GKS effectors would be expected to show a stronger phenotype.

E. cuniculi infection triggers IFNγ-dependent host cell death

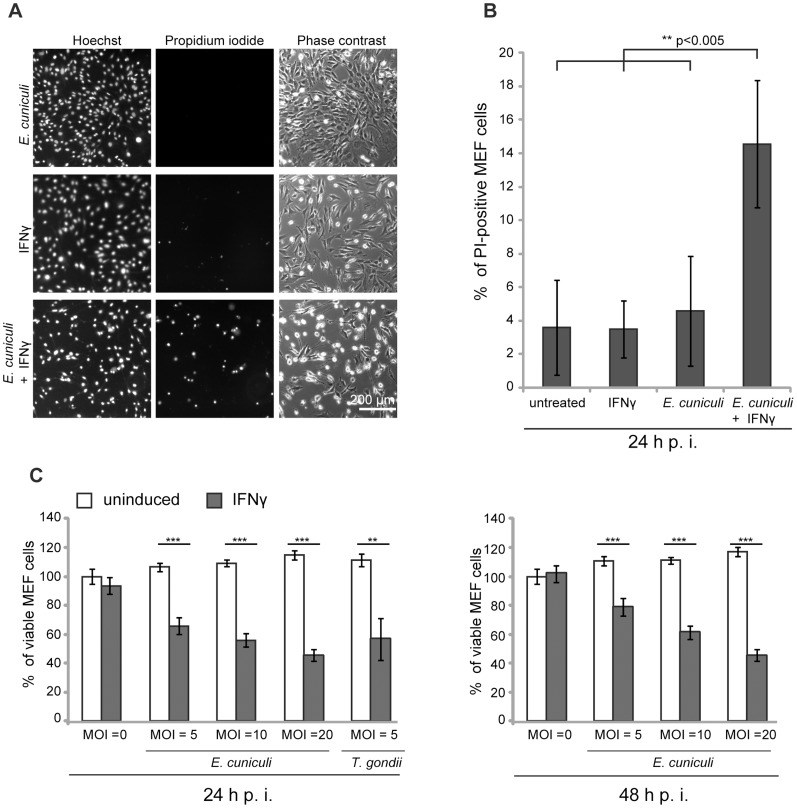

We and others have documented the direct disruption of the IRG protein-coated T. gondii PVM, followed by necrotic host cell death in mouse cells induced by IFNγ [4], [15], [20], [43]. It was of interest to find out whether this consequence of IRG protein action could also be observed in IFNγ-induced mouse cells infected with E. cuniculi. In the first experiments we stained infected primary MEF wildtype cells under live-cell conditions with the membrane-impermeable dye propidium iodide in order to stain nuclei of necrotic cells, and with the membrane–permeable dye Hoechst, which stains all nuclei. We found a significant excess of propidium iodide-positive nuclei in E. cuniculi infected and IFNγ-treated cells compared to untreated or single-treated control samples (Figure 5A, B). Next, we used a standard formazan-based colorimetric assay to measure viability of MEF wildtype cells with increasing multiplicity of infection with E. cuniculi. At one day post infection, viability of infected cells was significantly reduced in dependence of IFNγ-induction and this was even more pronounced at 2 days post infection (Figure 5C). Thus, in the presence of IFNγ, E. cuniculi infection seems to induce the same response as T. gondii, namely reactive death of the host cell itself.

Figure 5. E. cuniculi infection triggers IFNγ-dependent host cell death.

(A) Wt MEFs were induced with IFNγ for 24 h and then infected with E. cuniculi spores for 24 h or left untreated. Without fixation, the cells were stained with Hoechst and Propidium iodide dye, photographed under live-cell conditions and automatically enumerated. (B) Quantification of A, graph represents mean values +/− SD from five independent experiments. (C) Wt MEFs were seeded in 96-wells and induced with IFNγ for 24 h (black bars) or left untreated (white bars). Cells were infected with E. cuniculi spores at different MOIs (MOI = 5–20) or with T. gondii Me49 tachyzoites (MOI = 5) as positive control. Cell viability was measured with a formazan-based colorimetric assay 24 h or 48 h post infection and expressed as percentages of uninduced uninfected control cells. Graph represents mean value +/− SD of triplicates of one representative experiment. Three independent experiments were performed; Significance was calculated with two-tailed T-Test: ** p>0.005, *** p>0.0005.

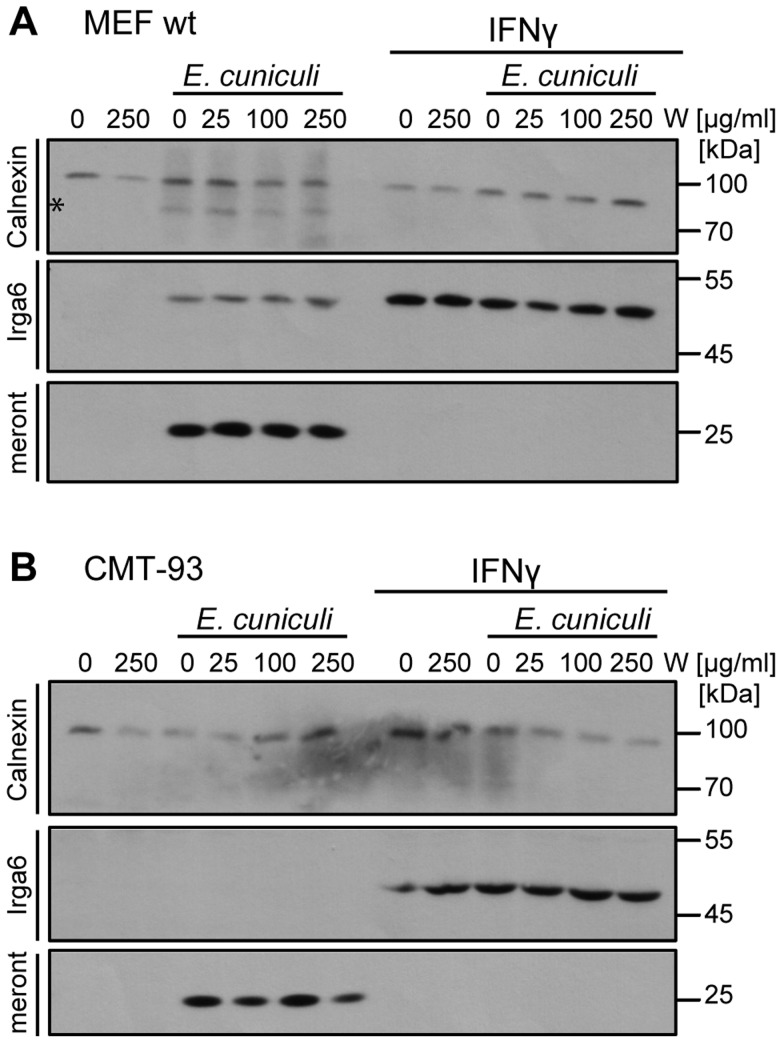

IDO is not responsible for IFNγ-mediated E. cuniculi restriction

Restricting nutrient acquisition is a common defence mechanism against intracellular parasites. Deprivation of tryptophan by the IFN-inducible indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is often claimed to be the main inhibitor of T. gondii replication in IFNγ-induced human fibroblasts [reviewed in [44], [45]], following reports that replication can be rescued by supplementation of the medium with tryptophan [46], [47]. IDO-mediated growth restriction of E. intestinalis has been proposed following observations in a mouse enterocytic cell line CMT-93 [33]. However, another study in activated mouse peritoneal macrophages showed that L-tryptophan supplementation failed to rescue the infection [48]. In view of these apparently inconsistent results, we analysed E. cuniculi growth in IFNγ-induced mouse cells following tryptophan supplementation (Figure 6). In wildtype MEF cells, as well as in CMT-93 cells, IFNγ-mediated growth restriction on E. cuniculi could not be reversed by supplementation with excess tryptophan, arguing strongly against mediation of the inhibition via IDO. Taken together with the complete loss of resistance caused by IRG protein deficiencies, we conclude that the IFNγ-mediated restriction of E. cuniculi in non-myeloid cells is mediated exclusively by the IRG system in mice.

Figure 6. Tryptophan supplementation cannot reverse the IFNγ-mediated E. cuniculi restriction.

C57/BL/6 MEFs (A) or mouse enterocytic CMT-93 cells (B) were treated with IFNγ for 24 h or left uninduced. Indicated doses of L-Tryptophan (W) were added to the medium 30 minutes prior infection with E. cuniculi spores. Cell lysates were prepared 5 days post infection and separated by one SDS-PAGE. Western blots were cut into three regions probed simultaneously with for anti-meront mAB 6G2, anti-Calnexin pAB as loading control and anti-Irga6 (10E7 mAB) as IFNγ-induction control. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

The IFN-inducible IRG proteins of the mouse are essential for resistance against some strains of the intracellular bacterium, Chlamydia, and against the intracellular protozoon, Toxoplasma gondii, but seem to play no role in resistance against a multitude of other intracellular bacterial and protozoal infections. The combination of selectivity and lack of phylogenetic consistency in IRG protein action calls for a mechanistic explanation that unifies the two widely disparate target species while excluding organisms that do not engage the IRG system. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that the key lies in how different organisms enter the host cell. Most of the organisms that are ignored by the IRG system, such as Salmonella, Listeria, Leishmania, Mycobacteria, and Rhodococcus, engage the phagocytic mechanism and are taken up into and reside, whether temporarily or permanently, in more or less modified phagosomes. In contrast T. gondii typically enters actively using force generated by its own cortical cytoskeleton without engaging the phagocytic mechanism [reviewed in [49], [50]]. However, it has recently been described that T. gondii may enter macrophages, but not fibroblasts, by phagocytic uptake, but this is followed by active exit from the phagosome into a conventional parasitophorous vacuole and the loading of Irgb6 appears to be unaffected [51]. Chlamydia is taken up by an unknown process with some features of clathrin-mediated endocytosis but none of phagocytosis [52]. With this disparity in mind, the working hypothesis behind this paper was that organisms that enter cells without engaging the phagocytic mechanism may become preferential targets for IRG protein-mediated resistance, regardless of their taxonomic status. To generalise this idea, we tested another intracellular organism with an anomalous, non-phagocytic mode of cellular invasion and a wide taxonomic divergence from the other two known IRG protein targets: the microsporidian, Encephalitozoon cuniculi.

The unambiguous conclusion from our experiments is that infection by E. cuniculi is resisted in IFNγ-induced mouse fibroblasts by the action of the IRG proteins, and several aspects of the process closely resemble features that have been studied in detail in T. gondii infection. Resistance is associated with accumulation of IRG proteins onto at least a proportion of the intracellular organisms within the first 30 minutes after infection, a time at which IRG protein accumulation onto the T. gondii vacuolar membrane is already well-advanced [18]. At the light microscopical level it is not possible to say precisely where the IRG proteins are localised, but images from later time points after infection, when the vacuole is enlarged and the PVM is separated from the organism by an intravacuolar space, suggest that the IRG proteins are loaded onto the parasitophorous vacuole membrane.

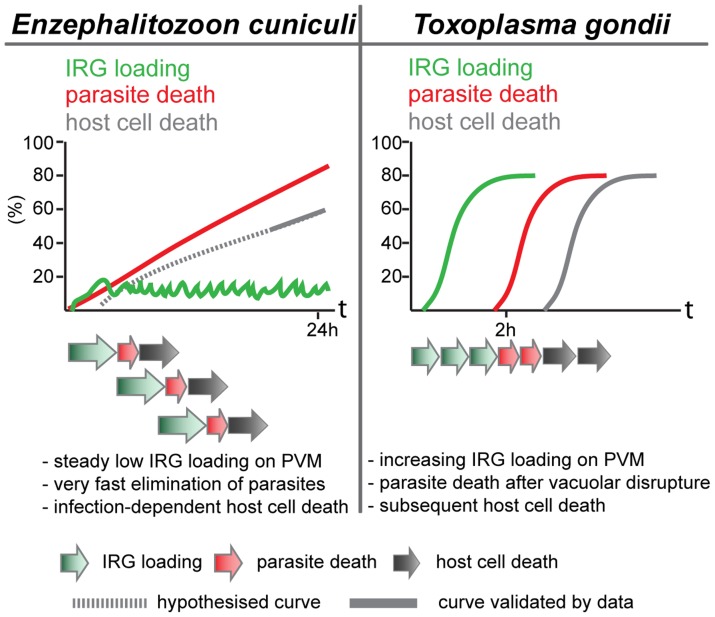

The cooperative pattern of loading of the different IRG proteins is also familiar from T. gondii. The frequency of vacuoles loaded at any time is low, but the majority of vacuoles carry more than one IRG protein (Figure 3). This result could of course also arise if only a few vacuoles are receptive to IRG proteins at any time. However, data from T. gondii showed that the loading of Irgb6 was stabilised and enhanced by the loading of Irga6, and thus clearly cooperative [18]. There is also a tendency in the E. cuniculi infection, perhaps not so well marked as in T. gondii infection, for Irgb6 to load more vacuoles than Irga6, and Irgd to load fewer. Also, as in T. gondii [1], [4] and in C. trachomatis infection [8], [10], [23], the IRG regulatory protein, Irgm1, does not load onto any E. cuniculi vacuoles, while Irgm2 can be found on some. In another respect, however, the loading of E. cuniculi vacuoles with IRG proteins appears to be different from the loading of T. gondii vacuoles. With avirulent T. gondii, the number of vacuoles loaded with IRG proteins rises to as much as 90% of all vacuoles within 2 h after infection. With E. cuniculi, the number of vacuoles loaded reaches a plateau between 5 and 15% within 30 minutes of infection, and persists at that level for many hours while the number of live meronts progressively falls (Figure 2). These different loading behaviours can be reconciled with qualitatively similar processes operating on the vacuoles of both organisms, if the initiation of IRG protein loading onto individual E. cuniculi vacuoles takes on average longer than onto T. gondii vacuoles, and if E. cuniculi vacuoles subsequently disintegrate and are cleared with faster kinetics than T. gondii vacuoles. With increasing time after infection more and more parasites are cleared from the cells, accounting for the long, slow loss of detectable meronts (Figure 1) reaching about 90% only 24 h after infection (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Scheme of different dynamics of IRG action.

Upon E. cuniculi infection, a low but steady number of IRG-positive vacuoles can be detected over the first 24 h post infection accompanied by a continuous loss of viable meronts. Moreover, host cell death is triggered by the combination of E. cuniculi infection and IFNγ induction. Initiation of IRG loading might be a stochastic and asynchronous event that is followed by a rapid elimination of the pathogen. In contrast, IRG loading on PVs of avirulent T. gondii strains starts immediately after parasite invasion. IRG-positive vacuoles seem to accumulate reaching a maximum at about 2 h post infection. When fully loaded, the vacuoles disrupt followed by T. gondii death and host cell death in an invariant order.

Light microscopy does not allow us to see exactly what happens to E. cuniculi vacuoles after loading with IRG proteins. Clear-cut disruption typical of the IRG-loaded T. gondii vacuole [20] is not easy to register. Nevertheless the vacuoles and their included parasites disappear (see Figure S1). In T. gondii, the disruption of the vacuole is followed within about 20 minutes by the death of the parasite and after an hour or two by the necrotic death of the infected cell. We also observed an excess of dead, presumably necrotic, cells in IFNγ-induced fibroblasts infected with E. cuniculi.

Lastly, as with T. gondii resistance, the IRG system appears to be the only mechanism in IFNγ-induced mouse fibroblasts that is capable of restriction of E. cuniculi. In fibroblasts from mice double deficient for the regulator IRG proteins, Irgm1 and Irgm3, in which the whole IRG system is largely disabled, all IFNγ-inducible resistance against the growth and development of the parasite was lost, and the IFNγ-inducible catabolic enzyme for tryptophan played no role in resistance against E. cuniculi.

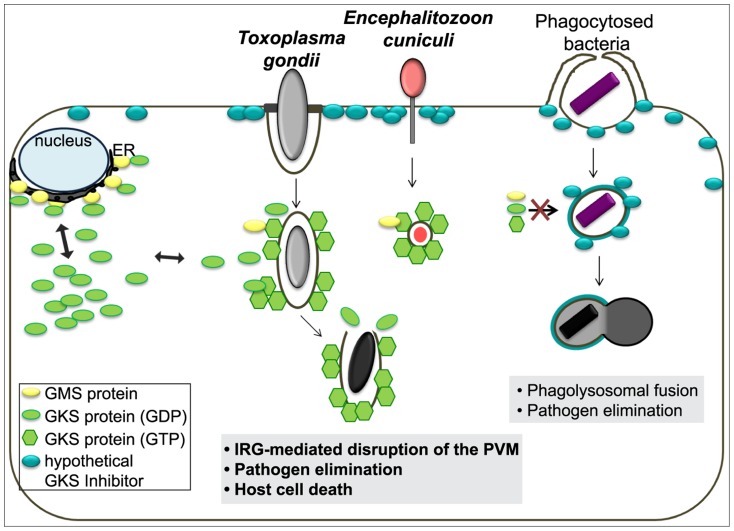

In summary, every property of the IRG-dependent resistance mechanism that has been analysed for T. gondii is probably also valid against E. cuniculi, and, to the extent that it is known, also against Chlamydia. Since effective resistance dependent on IRG proteins seems to be perfectly correlated with the accumulation of IRG proteins on the parasitophorous vacuole, the challenge is to determine the common factor that enables IRG proteins to accumulate on the vacuoles of these three organisms but not on the vacuoles of other organisms. These three organisms cover three kingdoms of life: protozoa, bacteria, and fungi. The broad phylogenetic distribution makes it unlikely a priori that the IRG proteins target a common ligand expressed by all restricted pathogens on their vacuolar membranes. Our preferred view builds on a hypothesis first formulated by Martens [53] to account for the targeting of IRG proteins to the T. gondii vacuole rather than to other cellular organelles. Martens proposed the existence of a self-derived factor X expressed on the membranes of cellular organelles that inhibits the accumulation and activation of IRG proteins on these sites, thereby protecting these organelles from IRG protein mediated damage. Parasitophorous vacuoles, lacking factor X, would be exposed to IRG accumulation and activation. This elegant “missing self” model was confirmed some time later and “factor X” was revealed to be the three GMS proteins, Irgm1, Irgm2 and Irgm3, which are bound to distinct subsets of organellar membranes and act as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors of the effector GKS proteins at these sites [16]. In the absence of one or more GMS proteins, GKS proteins form activated, GTP-bound assemblies in the cytoplasm, probably associated with “unprotected” organellar membranes [23], [41]. The GMS IRG proteins seem to fulfil exactly the role of Martens' Factor X for the distinction between intracellular organelles and a parasitophorous vacuole. However, GKS effector IRG proteins do not accumulate or activate on the plasma membrane, which to the best of our knowledge is not protected by any GMS protein. We are therefore forced to introduce a new hypothetical inhibitor associated with the plasma membrane that inhibits GKS activation at that location (Figure 8). Parasitophorous vacuoles are formed by invagination of the plasma membrane, and as we know with some precision from experiments with T. gondii, the vacuoles are receptive to IRG loading and activation immediately after parasite entry [18]. Thus entry of the parasite and formation of the parasitophorous vacuole must entail loss of the hypothetical plasma membrane-bound inhibitor. We propose that this is the essential distinction between those organisms that do, and those that do not, engage the IRG system, and that loss of the plasma membrane inhibitor is due to the unusual, non-phagocytic entry mechanisms of all three parasites.

Figure 8. Scheme of the IRG resistance system and its target organisms.

In IFNγ-stimulated mouse cells, GMS proteins localise mainly to endomembranes such as the ER and keep membrane-bound or cytosolic GKS proteins in a GDP-bound inactive state. Our current view is that the plasma membrane is protected by a hypothetical unknown factor that inhibits GKS protein-mediated damage. During host cell infection by T. gondii or E. cuniculi, invagination of the plasma membrane creates a parasitophorous vacuole that excludes the hypothetical factor and also does not carry GMS proteins. This “missing-self” allows GKS proteins to activate and accumulate on the PVM leading to the PV disruption, pathogen elimination and ultimately host cell death. However, bacteria entering via phagocytic mechanisms do not actively exclude the hypothetical factor and are therefore targeted for endolysosomal degradation.

Recently, the Atg5-dependent module of the ubiquitin-like conjugation system of autophagy has been proposed to mediate IRG targeting to the vacuole of T. gondii [19], [54], [55]. But since IRG and GBP proteins in Atg5−/− cells form cytosolic GTP-bound aggregates [18], [19], [55] which are unable to target pathogens, loss of resistance appears rather to be caused by deregulated effector protein homeostasis. It has also been difficult to localise any autophagic component to T. gondii parasitophorous vacuoles [4]. Recent data from Choi et al. (2014) suggest occasional localisation of native LC3II at the PVM, but on only a small minority of vacuoles, uncorrelated with the presence of IRG proteins [54].

The entry of T. gondii into cells has been studied in considerable detail and probably provides the best system for establishing the identity of the plasma membrane inhibitor. Several categories of protein are depleted from the developing vacuolar membrane, presumably as a result of the sieving action of the parasite-derived RON protein complex formed at the moving junction through which the parasite enters the cell [56], [57], [58], [59]. Apart from transient activation of host actin at the moving junction [60], [61], there is also no evidence that components of the cortical cytoskeleton remain associated with the nascent vacuole.

In the case of Encephalitozoon cuniculi, electron microscopic studies suggested that the PV membrane is derived from the host cell [29]. Subsequent studies from Bohne and colleagues established that the early PVM is non-fusogenic and devoid of any endolysosomal markers immediately after invasion [39], and moreover that the lipids of the PVM are indeed host cell-derived and that the PVM also forms simultaneously with the extrusion of the sporoplasm. This is all consistent with the suggestion that the early PVM is an invagination of the host cell plasma membrane [28], [62]. Due to the high speed of host cell entry, we suggest that physical forces may determine the presence and composition of host cell surface proteins on the newly formed PVM, which would be a prerequisite of IRG protein recognition. Although E. cuniculi spores are actively phagocytosed by macrophages, this is unlikely to be a biologically significant entry route, because it does not contribute to the intracellular meront population in mouse macrophages [63] or mouse embryonic fibroblasts (unpublished results Springer-Frauenhoff).

This study was designed based on knowledge of the interaction of the mouse IRG protein system and T. gondii. We found four major similarities in the action of the IRG system in defense against E. cuniculi: (1) the relocalisation of multiple IRG proteins to the cytosolic face of the PVM; (2) cooperativity by double-loading; (3) IFNγ- and infection- dependent host cell death and (4) IDO-independent IFNγ-mediated restriction in mouse cells.

While the IRG system clearly plays an essential role in defending mice and probably other small rodents against certain infections, there is every reason to believe that the system is effectively completely absent from humans and higher primates, birds, cats and doubtless many other mammalian species too [21]. The sporadic occurrence of a developed IRG system among vertebrate groups suggests that its possession is costly and only justified when certain classes of parasite exert intense selection pressures [14].

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted under the regulations and protocols for animal experimentation according to the German “Tierschutzgesetz” (Animal Experimentation Law). The local government authorities, Landesamt für Natur- und Umweltschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen, and its ethics committee approved the work (LANUV Permit No. 84-02.05.40.14.004).

Cell culture

Primary C57BL/6 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were prepared from mice at day 14 post coitum. Irgm1−/−, Irgm3−/−, Irgm1/Irgm3−/−, Irgd −/− MEFs (kindly provided by Greg Taylor) or Irga6−/−MEFs [42] were immortalized by transfection of pSV3-neo plasmid [64] and pPur (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) in a ratio 9∶1 using FuGENE HD (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h, cells were put under selection with 3 µg/ml puromycin (Clontech). Primary and transformed MEFs as well as mouse rectal carcinoma CMT-93 cells (ATCC CCL-223) were cultured in DMEM, high glucose (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× MEM non-essential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (all PAA, Pasching, Austria). Human foreskin fibroblasts (Hs27; ATCC CRL-1634) were cultured in IMDM, high glucose (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (PAA). Cells were stimulated with 200 U/ml of mouse IFNγ (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) for 24 h. For IDO-inhibition, L-tryptophan (W) (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Saint Louis, MO, USA) was added 15 min prior to infection.

In vitro passage of E. cuniculi and infection of mouse fibroblasts

E. cuniculi spores were a generous gift from Prof. Peter Deplazes (University of Zürich, Switzerland). Spores were routinely propagated in Hs27 cells as described in [62]. Briefly, infected monolayers were scraped 7–12 days post infection and the suspension was passed through a 26G needle. The first centrifugation (10 min at 500 rpm) removed the host cell debris, whereas the second centrifugation (20 min at 2500 rpm) sedimented the spores. A stock solution with 4×107 spores/ml PBS was stored at 4°C for max. 3 month. For infection assays, 8–12×104 host cells were seeded in 6-well plates 48 h prior infection, optionally stimulated, and infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 parasites per host cell for microscopic assays and MOI 5 for Western Blot analysis. In order to obtain synchronous infection, spores were allowed to infect the cells for 2–4 h followed by one careful washing step with PBS and addition of fresh medium. Cells were fixed or harvested at the indicated time points post infection. For E. cuniculi genotyping, 60×107 E. cuniculi spores were centrifuged for 20 min at 2500 rpm, resuspended in 200 µl PBS and 20 µl of Proteinase K, DNA was isolated with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufactures instructions. The rRNA gene region of large (LSU rRNA) and small ribosomal subunit (SSU rRNA) and ITS region were amplified as described in [65]. The E. cuniculi stain used in this study had the genotype I.

Immunological reagents

The following immunoreagents were used: rabbit anti-Irgm1 polyclonal antiserum (pAS) rbMAE15 [66], rabbit anti-Irgm2 pAS H53/3 [4], [18], rabbit anti-Irga6 pAS 165/3 [67], anti-Irga6 mouse monoclonal antibody (mAB) 10D7/10E7 [17], anti-Irgb6 mouse mAB B34 [68], anti-Irgb6 goat polyclonal antibody (pAB) A20 (sc-11079, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-meront mouse mAB 6G2 [39], anti-SWP1 [69], anti-Calnexin rabbit (pAB) (Calbiochem Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488/555/647-labeled donkey anti-mouse, -rabbit, and -goat antisera (all Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Life Technology), donkey anti-rabbit- (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany), and goat anti-mouse-HRP (horseradish peroxidase) (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bonn, Germany) antisera. 4′, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used for nuclear staining at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was carried out on paraformaldehyde-fixed cells grown on glass cover slips as described earlier [4]. In brief, cells were permeabilized and blocked with 3% BSA and 0.1% saponin (both Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) in PBS, stained with the primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C following incubation with the secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Between all steps cells were triple washed with 0.1% saponin in PBS and then mounted on glass microscopic slides in ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen Life Technology). The images were taken with an Axioplan II fluorescence microscope and AxioCam MRm camera and processed by Axiovision 4.7 (all Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). All samples were counted blind.

Live cell imaging

Live cell imaging was performed in μ-slide I chambers (Ibidi, Munich, Germany) as described earlier [20]. For live cell experiments, wt MEF cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP-N3-Irga6-ctag1 [20] using FuGENE HD (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions and induced with 200 U/ml IFNγ. After 24 hours cells were infected with E. cuniculi spores at a MOI 50 in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 (PAA). After infection with E. cuniculi, the cells were observed with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M motorized microscope fitted with a wrap-around temperature-controlled chamber (Zeiss). The time-lapse images were obtained and processed by Axiovision 4.6 software (Zeiss).

SDS-PAGE and western blot

At 2 or 5 days post infection, MEF or CMT-93 cells were washed with PBS once and directly lysed in 200 µl 2× SDS sample buffer (2% SDS, 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.8), 10% Glycerol, 0.005% bromophenol blue, 1.4% β-mercaptoethanol). The lysates were transferred into Eppendorf tubes and boiled 5–10 min at 95°C. 15–20 µl were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Protein transfer was confirmed by staining the nitrocellulose membranes with Ponceau S solution [0.2% Ponceau S (Roth) and 3% acetic acid in dH2O]. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS and probed for the proteins of interest with the indicated primary and HRP-coupled secondary antibodies.

Cell viability assay

Primary MEF cells (5000 cells/96-well) were seeded and induced with IFNγ for 24 h or left untreated. The cells were then infected with E. cuniculi spores at the indicated MOI for 24 h or 48 h. Thereafter, viable cells were quantified by the CellTiter 96 AQueous non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Infection with avirulent T. gondii Me49 served as positive control [20].

Cell necrosis assay

MEF cells grown in 6 cm-dishes were induced with IFNγ for 24 h and infected with E. cuniculi spores at a MOI 10. At 24 h post infection, Bisbenzimide Hoechst 33342 and Propidium Iodide (both Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the medium (1 µg/ml final concentration for both) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. 10 fluorescent pictures per sample were photographed with the Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope with a 10 fold magnification. Total cell number (Hoechst-positive nuclei) and dead cells (PI-positive nuclei) were automatically enumerated using the Volocity software (PerkinElmer, Santa Clara, CA, USA). At least 500 cells were counted per sample and percentage of dead cells per total cell number was calculated. In five independent experiments, a total of 10.000 cells or more was counted per sample.

Supporting Information

IRG proteins load onto the E. cuniculi PVM in a time-dependent manner. MEFs were transiently transfected with Irga6-ctag1-EGFP and induced with IFNγ for 24 hours. Cells were infected with E. cuniculi spores at a MOI 50 and analyzed with time lapse video microscopy starting 5 h post infection (A) or 20 post infection (B). (A) The top panel shows the green fluorescent channel only, the arrow points at the Irga6-EGFP ring which seems to break up within the next 37 minutes. The white box shown as inset is the magnified area of interest. The panel below shows the corresponding phase contrast images. Transects were drawn through the meront (dashed white line) and the profiles below show the pixel intensity of IRG staining within this transect. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) On the top, merged images of green fluorescence and phase contrast are shown for the start and end point of the time laps series. The magnified area within the white box of the green fluorescent channel only is shown below in the zoom in pictures as time series. Irga6 protein seems to accumulate as a ring-like structure within 20 minutes and then the level decreases again. Transects were drawn through the meront (white line marked by the arrow head) and the profiles below show the pixel intensity of IRG staining within this transect.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Jingtao Lilue for help in genotyping the E. cuniculi strain. We thank Claudia Poschner for great technical assistance. We thank all the lab members of the Howard group for critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Gregory Taylor for providing IRG knock-out cells.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The Cologne laboratory was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB635, 670, 680, SPP1399 to JCH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Butcher BA, Greene RI, Henry SC, Annecharico KL, Weinberg JB, et al. (2005) p47 GTPases regulate Toxoplasma gondii survival in activated macrophages. Infect Immun 73: 3278–3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collazo CM, Yap GS, Sempowski GD, Lusby KC, Tessarollo L, et al. (2001) Inactivation of LRG-47 and IRG-47 reveals a family of interferon gamma-inducible genes with essential, pathogen-specific roles in resistance to infection. J Exp Med 194: 181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ling YM, Shaw MH, Ayala C, Coppens I, Taylor GA, et al. (2006) Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J Exp Med 203: 2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martens S, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Griffiths G, Schell G, et al. (2005) Disruption of Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuoles by the mouse p47-resistance GTPases. PLoS Pathog 1: e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taylor GA, Collazo CM, Yap GS, Nguyen K, Gregorio TA, et al. (2000) Pathogen-specific loss of host resistance in mice lacking the IFN-gamma-inducible gene IGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 751–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reid AJ, Vermont SJ, Cotton JA, Harris D, Hill-Cawthorne GA, et al. (2012) Comparative genomics of the apicomplexan parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum: Coccidia differing in host range and transmission strategy. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spekker K, Leineweber M, Degrandi D, Ince V, Brunder S, et al. (2013) Antimicrobial effects of murine mesenchymal stromal cells directed against Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum: role of immunity-related GTPases (IRGs) and guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs). Med Microbiol Immunol 202: 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HM, Braun PR, Zerrahn J, Meyer TF (2009) IFN-gamma-inducible Irga6 mediates host resistance against Chlamydia trachomatis via autophagy. PLoS One 4: e4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bernstein-Hanley I, Coers J, Balsara ZR, Taylor GA, Starnbach MN, et al. (2006) The p47 GTPases Igtp and Irgb10 map to the Chlamydia trachomatis susceptibility locus Ctrq-3 and mediate cellular resistance in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 14092–14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coers J, Bernstein-Hanley I, Grotsky D, Parvanova I, Howard JC, et al. (2008) Chlamydia muridarum evades growth restriction by the IFN-gamma-inducible host resistance factor Irgb10. J Immunol 180: 6237–6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miyairi I, Tatireddigari VR, Mahdi OS, Rose LA, Belland RJ, et al. (2007) The p47 GTPases Iigp2 and Irgb10 regulate innate immunity and inflammation to murine Chlamydia psittaci infection. J Immunol 179: 1814–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson DE, Virok DP, Wood H, Roshick C, Johnson RM, et al. (2005) Chlamydial IFN-gamma immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 10658–10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howard JC, Hunn JP, Steinfeldt T (2011) The IRG protein-based resistance mechanism in mice and its relation to virulence in Toxoplasma gondii. Curr Opin Microbiol 14: 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lilue J, Muller UB, Steinfeldt T, Howard JC (2013) Reciprocal virulence and resistance polymorphism in the relationship between Toxoplasma gondii and the house mouse. Elife 2: e01298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao Y, Ferguson DJ, Wilson DC, Howard JC, Sibley LD, et al. (2009) Virulent Toxoplasma gondii evade immunity-related GTPase-mediated parasite vacuole disruption within primed macrophages. J Immunol 182: 3775–3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hunn JP, Koenen-Waisman S, Papic N, Schroeder N, Pawlowski N, et al. (2008) Regulatory interactions between IRG resistance GTPases in the cellular response to Toxoplasma gondii. Embo J 27: 2495–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Papic N, Hunn JP, Pawlowski N, Zerrahn J, Howard JC (2008) Inactive and active states of the interferon-inducible resistance GTPase, Irga6, in vivo. J Biol Chem 283: 32143–32151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Konen-Waisman S, Zhao YO, Preukschat D, et al. (2010) Coordinated loading of IRG resistance GTPases on to the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole. Cell Microbiol 12: 939–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, et al. (2008) Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 4: 458–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao YO, Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Howard JC (2009) Disruption of the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole by IFNgamma-inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) triggers necrotic cell death. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bekpen C, Hunn JP, Rohde C, Parvanova I, Guethlein L, et al. (2005) The interferon-inducible p47 (IRG) GTPases in vertebrates: loss of the cell autonomous resistance mechanism in the human lineage. Genome Biol 6: R92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boehm U, Guethlein L, Klamp T, Ozbek K, Schaub A, et al. (1998) Two families of GTPases dominate the complex cellular response to IFN-gamma. J Immunol 161: 6715–6723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haldar AK, Saka HA, Piro AS, Dunn JD, Henry SC, et al. (2013) IRG and GBP host resistance factors target aberrant, “non-self” vacuoles characterized by the missing of “self” IRGM proteins. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Capella-Gutierrez S, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T (2012) Phylogenomics supports microsporidia as the earliest diverging clade of sequenced fungi. BMC Biol 10: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. James TY, Pelin A, Bonen L, Ahrendt S, Sain D, et al. (2013) Shared signatures of parasitism and phylogenomics unite Cryptomycota and microsporidia. Curr Biol 23: 1548–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katinka MD, Duprat S, Cornillot E, Metenier G, Thomarat F, et al. (2001) Genome sequence and gene compaction of the eukaryote parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Nature 414: 450–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Didier ES (2005) Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop 94: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bohne W, Bottcher K, Gross U (2011) The parasitophorous vacuole of Encephalitozoon cuniculi: biogenesis and characteristics of the host cell-pathogen interface. Int J Med Microbiol 301: 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bigliardi E, Sacchi L (2001) Cell biology and invasion of the microsporidia. Microbes Infect 3: 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Didier ES (1995) Reactive nitrogen intermediates implicated in the inhibition of Encephalitozoon cuniculi (phylum microspora) replication in murine peritoneal macrophages. Parasite Immunol 17: 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jelinek J, Salat J, Sak B, Kopecky J (2007) Effects of interferon gamma and specific polyclonal antibody on the infection of murine peritoneal macrophages and murine macrophage cell line PMJ2-R with Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 54: 172–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khan IA, Moretto M (1999) Role of gamma interferon in cellular immune response against murine Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. Infect Immun 67: 1887–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choudhry N, Korbel DS, Zaalouk TK, Blanshard C, Bajaj-Elliott M, et al. (2009) Interferon-gamma-mediated activation of enterocytes in immunological control of Encephalitozoon intestinalis infection. Parasite Immunol 31: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fischer J, Tran D, Juneau R, Hale-Donze H (2008) Kinetics of Encephalitozoon spp. infection of human macrophages. J Parasitol 94: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El Fakhry Y, Achbarou A, Desportes I, Mazier D (2001) Resistance to Encephalitozoon intestinalis is associated with interferon-gamma and interleukin-2 cytokines in infected mice. Parasite Immunol 23: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. El Fakhry Y, Achbarou A, Franetich JF, Desportes-Livage I, Mazier D (2001) Dissemination of Encephalitozoon intestinalis, a causative agent of human microsporidiosis, in IFN-gamma receptor knockout mice. Parasite Immunol 23: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salat J, Sak B, Le T, Kopecky J (2004) Susceptibility of IFN-gamma or IL-12 knock-out and SCID mice to infection with two microsporidian species, Encephalitozoon cuniculi and E. intestinalis. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 51: 275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halonen SK, Taylor GA, Weiss LM (2001) Gamma interferon-induced inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii in astrocytes is mediated by IGTP. Infect Immun 69: 5573–5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fasshauer V, Gross U, Bohne W (2005) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Encephalitozoon cuniculi lacks host cell membrane proteins immediately after invasion. Eukaryot Cell 4: 221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Henry SC, Daniell XG, Burroughs AR, Indaram M, Howell DN, et al. (2009) Balance of Irgm protein activities determines IFN-gamma-induced host defense. J Leukoc Biol 85: 877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hunn JP, Howard JC (2010) The mouse resistance protein Irgm1 (LRG-47): a regulator or an effector of pathogen defense? PLoS Pathog 6: e1001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liesenfeld O, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Han SJ, Heinrich F, et al. (2011) The IFN-gamma-inducible GTPase, Irga6, protects mice against Toxoplasma gondii but not against Plasmodium berghei and some other intracellular pathogens. PLoS One 6: e20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melzer T, Duffy A, Weiss LM, Halonen SK (2008) The gamma interferon (IFN-gamma)-inducible GTP-binding protein IGTP is necessary for toxoplasma vacuolar disruption and induces parasite egression in IFN-gamma-stimulated astrocytes. Infect Immun 76: 4883–4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Konen-Waisman S, Howard JC (2007) Cell-autonomous immunity to Toxoplasma gondii in mouse and man. Microbes Infect 9: 1652–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. MacMicking JD (2012) Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 367–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Daubener W, Spors B, Hucke C, Adam R, Stins M, et al. (2001) Restriction of Toxoplasma gondii growth in human brain microvascular endothelial cells by activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Infect Immun 69: 6527–6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pfefferkorn ER (1984) Interferon gamma blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81: 908–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Didier ES, Bowers LC, Martin AD, Kuroda MJ, Khan IA, et al. (2010) Reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, and iron sequestration contribute to macrophage-mediated control of Encephalitozoon cuniculi (Phylum Microsporidia) infection in vitro and in vivo. Microbes Infect 12: 1244–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carruthers V, Boothroyd JC (2007) Pulling together: an integrated model of Toxoplasma cell invasion. Curr Opin Microbiol 10: 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sibley LD (2004) Intracellular parasite invasion strategies. Science 304: 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao Y, Marple AH, Ferguson DJ, Bzik DJ, Yap GS (2014) Avirulent strains of Toxoplasma gondii infect macrophages by active invasion from the phagosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 6437–6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hybiske K, Stephens RS (2007) Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis entry into nonphagocytic cells. Infect Immun 75: 3925–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martens S (2004) Cell-Biology of Interferon Inducible GTPases: University of Cologne.

- 54. Choi J, Park S, Biering SB, Selleck E, Liu CY, et al. (2014) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Toxoplasma gondii is targeted for disruption by ubiquitin-like conjugation systems of autophagy. Immunity 40: 924–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Selleck EM, Fentress SJ, Beatty WL, Degrandi D, Pfeffer K, et al. (2013) Guanylate-binding protein 1 (Gbp1) contributes to cell-autonomous immunity against Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Alexander DL, Mital J, Ward GE, Bradley P, Boothroyd JC (2005) Identification of the moving junction complex of Toxoplasma gondii: a collaboration between distinct secretory organelles. PLoS Pathog 1: e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Charron AJ, Sibley LD (2004) Molecular partitioning during host cell penetration by Toxoplasma gondii. Traffic 5: 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mordue DG, Desai N, Dustin M, Sibley LD (1999) Invasion by Toxoplasma gondii establishes a moving junction that selectively excludes host cell plasma membrane proteins on the basis of their membrane anchoring. J Exp Med 190: 1783–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tyler JS, Treeck M, Boothroyd JC (2011) Focus on the ringleader: the role of AMA1 in apicomplexan invasion and replication. Trends Parasitol 27: 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Delorme-Walker V, Abrivard M, Lagal V, Anderson K, Perazzi A, et al. (2012) Toxofilin upregulates the host cortical actin cytoskeleton dynamics, facilitating Toxoplasma invasion. J Cell Sci 125: 4333–4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gonzalez V, Combe A, David V, Malmquist NA, Delorme V, et al. (2009) Host cell entry by apicomplexa parasites requires actin polymerization in the host cell. Cell Host Microbe 5: 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ronnebaumer K, Gross U, Bohne W (2008) The nascent parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Encephalitozoon cuniculi is formed by host cell lipids and contains pores which allow nutrient uptake. Eukaryot Cell 7: 1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Orlik J, Bottcher K, Gross U, Bohne W (2010) Germination of phagocytosed E. cuniculi spores does not significantly contribute to parasitophorous vacuole formation in J774 cells. Parasitol Res 106: 753–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Southern PJ, Berg P (1982) Transformation of mammalian cells to antibiotic resistance with a bacterial gene under control of the SV40 early region promoter. J Mol Appl Genet 1: 327–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Valencakova A, Balent P, Ravaszova P, Horak A, Obornik M, et al. (2012) Molecular identification and genotyping of Microsporidia in selected hosts. Parasitol Res 110: 689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Springer HM, Schramm M, Taylor GA, Howard JC (2013) Irgm1 (LRG-47), a regulator of cell-autonomous immunity, does not localize to mycobacterial or listerial phagosomes in IFN-gamma-induced mouse cells. J Immunol 191: 1765–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Martens S, Sabel K, Lange R, Uthaiah R, Wolf E, et al. (2004) Mechanisms regulating the positioning of mouse p47 resistance GTPases LRG-47 and IIGP1 on cellular membranes: retargeting to plasma membrane induced by phagocytosis. J Immunol 173: 2594–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Carlow DA, Teh SJ, Teh HS (1998) Specific antiviral activity demonstrated by TGTP, a member of a new family of interferon-induced GTPases. J Immunol 161: 2348–2355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bohne W, Ferguson DJ, Kohler K, Gross U (2000) Developmental expression of a tandemly repeated, glycine- and serine-rich spore wall protein in the microsporidian pathogen Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Infect Immun 68: 2268–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

IRG proteins load onto the E. cuniculi PVM in a time-dependent manner. MEFs were transiently transfected with Irga6-ctag1-EGFP and induced with IFNγ for 24 hours. Cells were infected with E. cuniculi spores at a MOI 50 and analyzed with time lapse video microscopy starting 5 h post infection (A) or 20 post infection (B). (A) The top panel shows the green fluorescent channel only, the arrow points at the Irga6-EGFP ring which seems to break up within the next 37 minutes. The white box shown as inset is the magnified area of interest. The panel below shows the corresponding phase contrast images. Transects were drawn through the meront (dashed white line) and the profiles below show the pixel intensity of IRG staining within this transect. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) On the top, merged images of green fluorescence and phase contrast are shown for the start and end point of the time laps series. The magnified area within the white box of the green fluorescent channel only is shown below in the zoom in pictures as time series. Irga6 protein seems to accumulate as a ring-like structure within 20 minutes and then the level decreases again. Transects were drawn through the meront (white line marked by the arrow head) and the profiles below show the pixel intensity of IRG staining within this transect.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.