Abstract

Background & Aims

Among patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis (UC), lower fecal concentrations of calprotectin are associated with lower rates of relapse. We performed an open-label, randomized, controlled trial to investigate whether increasing doses mesalamine reduce concentrations of fecal calprotectin (FC) in patients with quiescent UC.

Methods

We screened 119 patients with UC in remission, based on Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index scores, FC >50 mcg/g, and intake of no more than 3g/day of mesalamine. Participants taking mesalamine formulations other than multimatrix mesalamine were switched to multimatrix mesalamine (2.4 g/day) for 6 weeks; 52 participants were then randomly assigned (1:1) to a group that continued its current dose of mesalamine (controls, n=26) or a group that increased its dose by 2.4 g/day for 6 weeks (n=26). The primary outcome was continued remission with FC<50 mcg/g. Secondary outcomes were continued remission with FC<100 mcg/g or <200 mcg/g (among patients with pre-randomization values above these levels).

Results

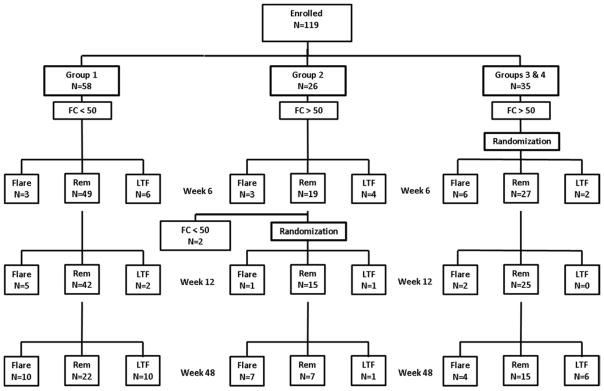

The primary outcome was achieved by 3.8% of controls and 26.9% of the dose escalation group (P=.0496). More patients in the dose escalation group reduced FC to below 100 mcg/g (P=.04) and 200 mcg/g (P=.005). Among the patients who were still in remission after the randomization phase, clinical relapse occurred sooner in patients with FC >200 mcg/g compared to those with FC <200 mcg/g (P=.01).

Conclusion

Among patients with quiescent UC and increased levels of FC, increasing the dose of mesalamine by 2.4 g/day reduced fecal concentrations of calprotectin to those associated with lower rates of relapse. Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00652145

Keywords: MMX, biomarker, 5 aminosalicylate, 5-ASA, natural history

Endoscopically assessed mucosal healing is associated with improved outcomes for ulcerative colitis (UC).1 However, lower endoscopy to determine mucosal healing is invasive and costly. Because clinical assessment in asymptomatic UC patients can underestimate mucosal disease activity, surrogate biomarkers of endoscopic disease assessment are appealing.2

Calprotectin, a cytosolic protein in granulocytes, is stable and easily measurable in feces.2 In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, fecal calprotectin (FC) levels correlate with endoscopic assessment of disease activity2 and can predict relapse in quiescent UC.3 Therefore, FC measurement could obviate the need for invasive endoscopic disease assessment in many cases.

Mesalamine [5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA)] compounds are the most commonly used agents for the treatment of mild-to-moderate UC. However, it is unknown whether higher doses of 5-ASA are more effective as maintenance therapy as there are no controlled studies of 5-ASA doses above 1.6 g/day. Furthermore, data are lacking on whether higher doses of 5-ASA are more effective than lower doses to achieve mucosal healing in asymptomatic patients. The Dose Escalation and Remission (DEAR) study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine whether increasing the 5-ASA dose in patients with UC in clinical remission but with an elevated FC concentration would lead to a reduction in FC concentration.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

We conducted a multicenter RCT of increasing the dose of 5-ASA to reduce elevated FC concentration in patients with UC that are in clinical remission (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT00652145). The study protocol was approved by an ethics review board for each participating site. The authors had access to the study data, conducted the statistical analyses and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patients were eligible if they met the following criteria: documented UC on the basis of usual diagnostic criteria; age ≥18 years; a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI)4 <3 with no category value >1; ≤3 bowel movements per 24 hours at the time of enrollment; no visible blood in their bowel movements in the 3 days prior to enrollment; stable dose or no use of 5-ASA (oral, rectal or a combination of oral and rectal) for ≥4 weeks prior to enrollment; stable dose or no use of azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or methotrexate for ≥8 weeks prior to enrollment; and experienced ≥1 flare of UC in the preceding 2 years. Exclusion criteria are summarized in the Supplemental Methods.

Intervention

Patients with a FC concentration ≥50 mcg/g were included in the RCT and were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to continue their current 5-ASA dose or to increase the dose by 2.4 g/day for a period of 6 weeks. Thus, in the dose escalation arm, those who were not taking any 5-ASA at baseline increased to 2.4 g/day and those taking 2.4 g/day at baseline increased to 4.8 g/day. Patients with baseline FC concentrations <50mcg/g were included in the observational arm of the study and continued on their usual dose at the discretion of their treating physician. FC levels were determined by Genova Diagnostics, Inc.

Study Groups

Patients were categorized into 1 of 4 mutually exclusive groups based on their week 0 FC concentrations and their current medical therapy for UC (Supplemental Figure 1). The 4 study groups and their treatment protocols were as follows:

Group 1 – Patients with FC concentrations <50 mcg/g were retained in an observational follow-up study but were not included in the RCT.

Group 2 – Patients currently taking 5-ASA compounds (oral, rectal or a combination of oral and rectal) other than the multimatrix (MMX) formulation or taking 1.2 g/day of MMX mesalamine and with FC concentrations ≥50 mcg/g were switched to 2.4 g/day of MMX mesalamine for a period of 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, these patients had FC levels retested. At week 6, those with a FC concentrations <50 mcg/g (Group 2b) were retained in the observational follow-up study but were not included in the RCT. Those whose week 6 FC concentrations were ≥50 mcg/g (Group 2a) were randomly assigned to either maintain their current regimen (MMX mesalamine 2.4 g/day) (Group 2aSD) or increase to 4.8 g/day until week 12 (Group 2aID).

Group 3 - Patients taking 2.4 g/day of MMX mesalamine at the time of enrollment and with a baseline FC concentration ≥50 mcg/g were randomized to maintain their current regimen (2.4 g/day) (Group 3SD) or to increase to 4.8 g/day (Group 3ID). FC was measured again at week 6. If the week 6 FC measurement was <50 mcg/g, no change was made in the medication regimen. If the week 6 measurement of FC remained elevated, those who were randomized initially to remain at 2.4 g/day (Group 3SD) had their dose increased to 4.8 g/day.

Group 4 - Patients not taking 5-ASA medications at the time of screening and who had a baseline FC concentration ≥50 mcg/g were randomized to add MMX mesalamine 2.4 g/day (Group 4ID) or to continue on their current regimen without 5-ASA (Group 4SD). If the week 6 FC concentration was <50 mcg/g, no change was made in the medication regimen. If the week 6 FC concentration was ≥50 mcg/g, the dose was increased to 4.8 g/day regardless of the dose received during the first 6 weeks of the study.

Randomization

Randomization was stratified based on baseline 5-ASA (oral or rectal) and immunomodulator use (see Supplemental Methods for further details). The participant and their treating physician were aware of the treatment assignment but the laboratory performing the calprotectin assay was not.

Study Drug

Study medication, MMX mesalamine 1.2 g enteric coated tablets (Lialda®, Shire US, Wayne, PA), was sent by the University of Pennsylvania Investigational Drug Service directly to the patient unless the clinical site preferred to distribute the drug kits. After week 12, the 5-ASA dose and formulation could be adjusted at the discretion of the treating physician.

Follow-up

All patients that met entry criteria had FC concentration measured at week 0, 6, and 12. After the week 0 office visit, patients were contacted by phone at 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 weeks to obtain follow-up data.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of UC patients in clinical remission with FC concentration <50 mcg/g 6 weeks after randomization. The threshold of 50 mcg/g is the lowest typically used to discriminate between patients with and without active inflammation as assessed by colonoscopy.2 The primary comparison was between those remaining on the same dose of 5-ASA (Group A = subgroups 2aSD, 3SD, and 4SD) and those with an increase in dose (Group B = subgroups 2aID, 3ID, and 4ID). Patients who experienced a clinical relapse, defined as a SCCAI >4 or need to start new medications to treat relapse, were considered to have not responded to therapy, regardless of the FC concentration at that time. Secondary endpoints included the proportion of patients in remission with reduction of the FC concentration below 100 and 200 mcg/g among the subgroups with pre-randomization values above these levels. We also compared the proportion of patients with reduction in FC to below 50, 100, and 200 mcg/g and the mean change in FC concentration among the subgroup that completed 6 weeks of follow-up after randomization.

Statistical comparisons used the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The primary analyses were 2-sided tests of statistical significance performed using intention-to-treat principle. Participants who dropped out of the study prior to the endpoint assessment for any reason were considered treatment failures. Secondary analyses excluded participants who were lost to follow-up for reasons other than relapse of disease. Pre-specified subgroup and adjusted analyses are described in the Supplemental Methods.

As an exploratory aim, the log rank test was used to compare the time to clinical relapse by week 48 in several groups: those randomized to dose increase versus those randomized to continue on the same dose; among those still in remission at week 12 of the clinical trial, those with high versus low week 12 FC concentration; and those with baseline FC concentration <50 mcg/g versus those with baseline FC concentration ≥50 mcg/g.

Sample Size Assumptions

The primary objective was to compare the proportion of patients who achieved a reduction of the FC concentration to <50 mcg/g in the treatment arm compared to the control arm 6 weeks after randomization. At the time of the design of this trial, the median response rate in the previous clinical trials of low-dose 5-ASA for active UC was >40%1. Therefore we projected that 50% of patients would respond to dose escalation. Based on the high positive predictive value of elevated FC concentration for UC relapse3 and the median endoscopic remission rates observed in placebo arms of clinical trials5, we projected that 10% of control patients would have a spontaneous reduction in FC to <50 mcg/g. With a 1:1 ratio of patients in the 2 groups, a total of 60 patients were needed for 90% power and 80% power to detect a difference of 50% vs. 10% and 45% vs. 10%, respectively.

Results

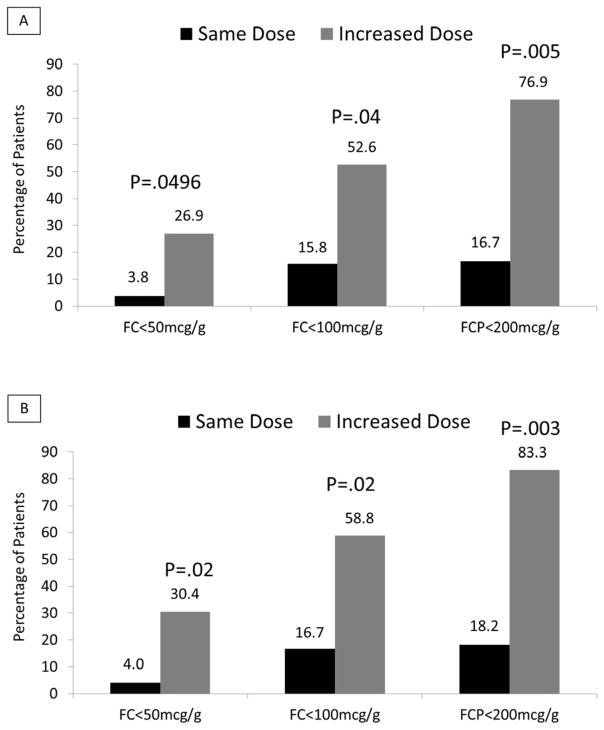

Between October 18, 2008 and March 16, 2012, from 150 screenings, 119 patients were enrolled, 58 with baseline FC concentration <50 mcg/g (Group 1) and 61 with an elevated baseline FC concentration (Groups 2, 3, and 4) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between the study groups. Patients with a baseline FC concentration <50 mcg/g trended towards having a longer median disease duration (p = 0.08) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Follow-up of patients in the randomized trial and the observational cohort. FC – Fecal calprotectin concentration in mcg/g. Flare – clinical relapse. REM – In clinical remission. LTF – Lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Group 1 (n=58) | Group 2 (n=26) | Group 3 (n=26) | Group 4 (n=9) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median years, IQR) | 46.5 (38.6–58.3) | 43.3 (33.5–55.4) | 43.9 (30.2–56.6) | 50.4 (42.5–57.1) | 0.35 |

| Male sex | 25 (43.1%) | 17 (65.4%) | 13 (50.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0.27 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 50 (89.3%) | 19 (79.2%) | 23 (88.5%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.58* |

| African American | 5 (8.9%) | 5 (20.8%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Native American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Multiracial | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Current | 4 (6.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.45 |

| Prior | 18 (31.0%) | 7 (26.9%) | 4 (15.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Never | 36 (62.1%) | 19 (73.1%) | 20 (76.9%) | 5 (55.6%) | |

| Extent of Disease | |||||

| Proctitis | 19 (33.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | 4 (16.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.27 |

| Left-sided | 22 (38.6%) | 11 (42.3%) | 11 (44.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Extensive | 16 (28.1%) | 9 (34.6%) | 10 (40.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Duration of UC (median years, IQR) | 13.8 (5.8–18.6) | 8.1 (3.5–15.3) | 6.5 (1.7–17.0) | 9.4 (2.1–19.8) | 0.08 |

| Duration of remission at baseline (median years, IQR) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | 0.70 |

| Baseline medications | |||||

| Oral 5-ASA | 49 (84.5%) | 21 (80.8%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.36 |

| Rectal 5-ASA | 6 (10.3%) | 9 (34.6%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.42 |

| Thiopurine | 11 (19.0%) | 3 (11.5%) | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | >0.99 |

| Prior medications | |||||

| Oral corticosteroids | 34 (59.6%) | 10 (38.5%) | 13 (50.0%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.36 |

| Cyclosporine | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| Anti-TNF agent | 3 (5.2%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | >0.99 |

| Rectal Steroids | 17 (29.3%) | 7 (26.9%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.68 |

| Baseline FC level (median, IQR) | 22.5 (1.0–33.0) | 254 (105–437) | 148 (65.0–675) | 142 (134–191) | <0.0001 |

Group 1 – Low baseline FC; Group 2 – High baseline FC and taking non-MMX formulated mesalamine; Group 3 – High baseline FC and taking 2.4 g/day of MMX mesalamine; Group 4 – High baseline FC and taking no mesalamine

P-value comparison White vs. Other

By week 12, 42 Group 1 patients (72%) were in remission, 8 (14%) were lost to follow-up and 8 (14%) flared. The median change in FC concentration between week 0 and 6 in the absence of relapse was 0 mcg/g (IQR: −17, 8).

Among the 61 patients with baseline FC concentration ≥50 mcg/g at week 0, 26 were taking another 5-ASA product at baseline and switched to MMX mesalamine 2.4 g/day. Of these, by week 6, 2 had a repeat FC concentration <50 mcg/g, 3 had a flare of UC and as such were not eligible for randomization, and 4 were non-compliant with study protocol or no longer interested in participating. The remaining 17 patients along with 26 patients with elevated FC on MMX mesalamine and 9 patients with elevated FC on no 5-ASA were randomized to 1 of the 2 treatment strategies (Group A - no increase in 5-ASA; Group B - increase in 5-ASA). The groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, race, smoking status, extent of disease, median disease duration and prior medical therapies (Table 2). The median baseline FC concentrations for groups A and B were 214 mcg/g (IQR: 80–675) and 174 mcg/g (IQR: 67.0–439), respectively (p = 0.42). At baseline, 5 patients (19%) in Group A and 4 (15%) in Group B were not taking 5-ASA (p = 0.71), and 4 patients (15%) in Group A and 6 (23%) in Group B were taking thiopurines (p = 0.73).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of treatment groups in the randomized controlled trial

| Group A* (n=26) | Group B* (n=26) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median years, IQR) | 48.8 (33.5–60.4) | 43.8 (30.5–57.1) | 0.71 |

| Male sex | 13 (50.0%) | 15 (57.7%) | 0.78 |

| Race | |||

| White | 21 (84.0%) | 22 (84.6%) | >0.99* |

| African American | 4 (16.0%) | 2 (7.7%) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| Native American | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.32 |

| Prior | 8 (30.8%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| Never | 16 (61.5%) | 20 (76.9%) | |

| Extent of Disease | |||

| Proctitis | 2 (8.0%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0.14 |

| Left-sided | 12 (48.0%) | 9 (34.6%) | |

| Extensive | 11 (44.0%) | 9 (34.6%) | |

| Duration of UC (median years, IQR) | 6.5 (2.2–11.9) | 11.9 (3.7–19.8) | 0.25 |

| Duration of remission at baseline (median years, IQR) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.3 (0.2–1.0) | 0.68 |

| FCP immediately prior to randomization (median, IQR) | 214 (80.0–675) | 174 (67.0–439) | 0.42 |

| Current Oral 5-ASA | 19 (73.1%) | 21 (80.8%) | 0.74 |

| Non-MMX formulation | 9 (34.6%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| MMX formulation | 12 (46.2%) | 14 (53.8%) | |

| Current Rectal 5-ASA | 2 (7.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | >0.99 |

| Current Thiopurine | 4 (15.4%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.73 |

| Prior Corticosteroids | 17 (65.4%) | 11 (42.3%) | 0.16 |

| Prior Rectal Corticosteroids | 7 (26.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | >0.99 |

| Prior Cyclosporine | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| Prior Anti-TNF agent | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0.49 |

Group A= no dose escalation, Group B= dose escalation

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of FC concentration <50 mcg/g without relapse at 6 weeks after randomization was achieved by 3.8% (1 of 26) of control patients (group A) and 26.9% (7 of 26) of patients randomized to dose escalation (group B) (p = 0.0496; number needed to treat 4.3). When excluding the dropouts from the analysis, 1 of 25 patients (4%) in group A compared to 7 of 23 (30.4%) in group B had a FC concentration <50 mcg/g 6 weeks after randomization (p = 0.02). Adjustment individually for age, smoking and extent of UC resulted in even stronger associations (data not shown).

Secondary Outcomes

More patients in group B (dose escalation) compared to group A achieved reduction in FC concentration below 100 mcg/g (p = 0.04) and 200 mcg/g (p = 0.005) (Figure 2). Subgroup analyses produced generally similar results although the statistical power was less (Table 3). Eleven patients in groups 3 and 4 (i.e., taking MMX mesalamine or no 5-ASA at baseline) who were still in remission at week 6 and had a persistently elevated FC concentration underwent dose escalation to 4.8 g/day. By week 12, 18.2%, 44.4%, and 66.7% had a FC <50, <100, and <200 mcg/g, respectively.

Figure 2.

FC levels were decreased in the group randomized to dose escalation. Panel A includes all randomized patients; those without a post randomization FC level are categorized as not achieving the outcome. Panel B includes only patients with a FC level measured after randomization or who experienced documented clinical relapse.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses

| FC < 50mcg/g | FC < 100 mcg/g# | FC < 200 mcg/g§ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Group A^ | Group B^ | P- value | Group A^ | Group B^ | P- value | Group A^ | Group B^ | P- value | |

| Baseline FC ≥185.5 | 0/13 | 4/13 | 0.10 | 1/13 | 8/13 | 0.01 | 2/12 | 10/13 | 0.005 |

| Baseline FC <185.5 | 1/13 | 3/13 | 0.59 | 2/6 | 2/6 | >0.99 | N/A* | N/A* | N/A* |

| Duration of current remission ≥0.4 years | 0/15 | 4/11 | 0.02 | 1/10 | 5/8 | 0.04 | 1/6 | 6/6 | 0.02 |

| Duration of current remission <0.4 years | 1/11 | 3/15 | 0.61 | 2/9 | 5/11 | 0.37 | 1/6 | 4/7 | 0.27 |

| Without 5-ASA use immediately prior to randomization† | 0/5 | 1/4 | 0.44 | 0/4 | 1/3 | 0.43 | 0/1 | 1/1 | >0.99 |

| With 5-ASA use immediately prior to randomization‡ | 1/21 | 6/22 | 0.09 | 3/15 | 9/16 | 0.07 | 2/11 | 9/12 | 0.01 |

| No baseline use of thiopurines | 1/22 | 6/20 | 0.04 | 3/16 | 8/14 | 0.06 | 1/10 | 9/11 | 0.002 |

| Baseline use of thiopurines | 0/4 | 1/6 | >0.99 | 0/3 | 2/5 | 0.46 | 1/2 | 1/2 | >0.99 |

| Proctitis | 0/2 | 1/8 | >0.99 | 1/2 | 2/6 | >0.99 | 1/2 | 1/2 | >0.99 |

| Left-sided | 0/12 | 4/9 | 0.02 | 1/8 | 6/7 | 0.01 | 1/5 | 6/7 | 0.07 |

| Extensive | 1/11 | 2/9 | 0.57 | 1/9 | 2/6 | 0.53 | 0/5 | 3/4 | 0.048 |

Limited to participants with pre-randomization FC concentration>100mcg/g

Limited to participants with pre-randomization FC concentration>200mcg/g

N/A = not applicable

Group A= no dose escalation; Group B= dose escalation

Group 4

Groups 2 and 3

The median change in FC concentration 6 weeks after randomization was −11 mcg/g (IQR: −231, 101) in Group A and −70 mcg/g (IQR: −378, 4) in Group B (p = 0.28). After adjustment for baseline FC concentration, the dose escalation group had a nearly statistically significant greater reduction (p = 0.06).

Clinical Relapse to Week 48

Time to clinical relapse did not differ between patients in group A compared to group B (p = 0.88). There was also no significant difference in time to relapse between patients with baseline FC concentration <50 mcg/g (Group 1) and those with FC concentration >50 mcg/g who were included in the RCT (Groups 2–4) (p = 0.44). Among the patients in the RCT who were still in remission at week 12, the time to clinical relapse was shorter in patients with FC concentration ≥200 mcg/g compared to those with FC concentration <200 mcg/g (p = 0.01) and nearly significantly shorter for patients with FC concentration ≥100 vs. <100 mcg/g (p = 0.09). No significant difference in time to relapse was observed for thresholds FC concentration <50 vs. ≥50 mcg/g (p = 0.33).

Adverse Events

Table 4 summarizes treatment emergent adverse events by 5-ASA dose at the time of the event. No serious adverse events occurred during the first 12 weeks of the study.

Table 4.

Adverse events observed during treatment with 2.4 and 4.8 g/day of mesalamine

| 2.4 g/day (n=27)^ | 4.8 g/day (n=49)^ | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific abdominal symptoms | 9* | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 1 |

| Bleeding | 4 | 0 |

| Worsening colitis | 1 | 0 |

| Constipation | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 1† | 3‡ |

| Other | 6# | 5## |

6 week treatment periods – patients could contribute up to 2 treatment periods to one dose level or 1 treatment period to both dose levels

Abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, mucous

Urinary tract infection

1 fungal infection; 2 upper respiratory infections

Acne, dry eyes, fatigue, headache, iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency

Dizziness, fever, itchy eyes, lower back pain, palpitations

Discussion

A primary objective in treating UC is the prevention of relapse. Observational studies have described reductions in FC concentration in patients with active UC upon treatment with infliximab6, 7, and that FC concentration can predict UC relapse following induction6 or during maintenance8 therapy with infliximab. The DEAR Study examined 5-ASA dose escalation in patients with quiescent UC but with an elevated FC concentration. Our study demonstrated that increasing the dose of 5-ASA in these patients led to a significant reduction and/or normalization of FC concentration. We further confirmed that an elevated FC concentration ≥ 200 mcg/g is associated with an increased risk of relapse. Finally, relapse rates did not differ for those with a low baseline FC concentration and those enrolled in the test-treat strategy clinical trial, suggesting that our intervention may decrease the rate of relapse.

We did not observe a difference in relapse rates between the 2 randomization arms of the trial or when comparing patients with an elevated baseline FC concentration enrolled in the RCT and patients with a normal baseline FC concentration. These findings may have been due to low statistical power or that the protocol included dose escalation to 4.8 g/day at week 6 if indicated by a persistently elevated FC concentration in groups 3 and 4. From week 7 to 12, >75% of randomized participants received 4.8 g/day.

A dose-response relationship of 5-ASA for the induction of remission in UC has been a topic of controversy. The ASCEND I and II trials suggested that patients with moderately active UC derived benefit from 5-ASA dosing at 4.8 g/day as compared to 2.4 g/day.9, 10 In contrast, the ASCEND III trial, restricted to patients with moderately active UC, demonstrated similar efficacy of 5-ASA at 4.8 versus 2.4 g/day, as defined by response or remission at week 6.11 However, this trial also found that remission rates at week 3 or 6 were significantly higher with the 4.8 g/day dose.11 Post-hoc analysis of the ASCEND I and II trials revealed higher rates of mucosal healing at week 6 with 4.8 g/day dosing.12 Subgroup analyses of ASCEND III showed benefit with higher-dose 5-ASA in subpopulations of patients previously treated with oral 5-ASA.11 Similarly, in the MMX mesalamine trials, 4.8 g/day of 5-ASA was more efficacious than 2.4 g/day in subpopulations of patients who had prior exposure to 5-ASA13 or had incomplete response to 8 weeks of MMX mesalamine at 2.4 g/day.14 Thus, taken together these data indicate that there may be a dose-response relationship with 5-ASA therapy in active UC.

Why there was not a more convincing dose-response relationship in these 5-ASA RCTs is unclear. A potential explanation was offered by Feagan et al., who demonstrated that assessment of severity of mucosal inflammation in multi-center clinical trials may be sufficiently inaccurate to obscure a true biological effect.15 In the present study, our use of FC concentration as an unbiased biomarker for mucosal disease, not subject to the individual variability seen with endoscopy grading, may explain why we found a more convincing dose-response relationship with 5-ASA therapy as compared to prior studies. Alternatively, the 5-ASA dose required to achieve a reduction in FC concentration may differ from that required to achieve the clinical and/or endoscopic outcomes used in the ASCEND and MMX trials.

Our study has several limitations. We used an open label design. However, the laboratory measuring FC levels was blinded to treatment assignment. Additionally, the open label design would be expected to bias toward the null if patients randomized to low dose took extra 5-ASA or vice versa. The sample size was relatively small, and thus there is a possibility of residual confounding. However, prespecified analyses stratified by and adjusting for baseline characteristics econfounding that would negate the observed association. Another limitation was the inability to accurately measure adherence, as much of the data was collected by telephone. We chose this design so as to not interfere with routine clinical care and to optimize our ability to recruit asymptomatic patients. For the same reasons, we did not obtain any data on endoscopic appearance during this study. Although numerous different FC concentrations have been recommended as cutoffs to identify active inflammation and to predict relapse, the intervention was as or more effective for secondary outcomes of higher FC cutoffs. Finally, we studied a single formulation of 5-ASA and a single dose escalation amount. As such, we cannot state whether similar results would be observed with lower dose escalation amounts or with other 5-ASA formulations, although a Cochrane review concluded that “there does not appear to be any differences in efficacy or safety among the various formulations.”16

Our study adds to the evidence supporting FC concentration as a valid biomarker for UC. Perhaps more importantly, our results offer a novel way to utilize FC testing to positively impact outcomes in UC. We demonstrated efficacy of intervention to reduce FC (a surrogate for mucosal inflammation) before symptoms develop in patients at potentially increased risk of relapse. If a subsequent RCT with the primary aim of demonstrating a reduction in relapse rate with 5-ASA dose escalation in patients with increased FC concentration were to extend our findings, there would be compelling evidence to support a paradigm shift in the management of quiescent UC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (K24-DK078228, K24-DK-078228-02S1) and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Shire Pharmaceuticals was provided with an earlier draft of the manuscript and was able to make comments but the authors had final decision on the content of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest:

Dr. Osterman – Consultant for Abbvie, Elan, Janssen, UCB; Research funding from UCB.

Dr. Aberra – Consultant for Janssen, Research investigator for Amgen, Janssen, UCB.

Dr. Lewis – Consultant for Elan, Proctor & Gamble, GlaxoSmithKline, Allos Therapeutics, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Prometheus, Lilly, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Merck; Research funding from Centocor, Takeda, Bayer.

Dr. Shafran reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Ms. Nessel reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Dr. Hardi – Consultant for Abbvie, Takeda, Santarus

Dr. McCabe – AbbVie Speakers Bureau

Dr. Cross – Consultant for Abbvie and Janssen; Educational and Research Funding from Abbvie, Janssen, and UCB..

Dr. Wolf – Consultant for AbbVie, Centocor, Salix, Warner Chilcot, Research investigator for Genetech, Millennium Research Group, Pfizer, Receptos

Dr. Liakos reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Ms. Gilroy reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Ms. Brensinger reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Author roles

Osterman - Study concept and design; Drafting of the manuscript; Analysis and interpretation of data

Aberra - Study concept and design; Drafting of the manuscript; Analysis and interpretation of data

Cross - Study concept and design; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Analysis and interpretation of data

Liakos - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Analysis and interpretation of data

McCabe - Study concept and design; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Analysis and interpretation of data

Wolf - Study concept and design; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Analysis and interpretation of data

Hardi - Study concept and design; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Analysis and interpretation of data

Nessel - Study concept and design; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Technical or material support; Study supervision; Analysis and interpretation of data

Brensinger - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Statistical analysis;

Gilroy - Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Acquisition of data; Technical or material support; Analysis and interpretation of data

Lewis - Study concept and design; Drafting of the manuscript; Statistical analysis; Obtained funding; Acquisition of data; Study supervision; Analysis and interpretation of data

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Froslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis JD. The utility of biomarkers in the diagnosis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1817–1826. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao R, Xiao YL, Gao X, et al. Fecal calprotectin in predicting relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18:1894–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su C, Lewis JD, Goldberg B, et al. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:516–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molander P, af Bjorkesten CG, Mustonen H, et al. Fecal calprotectin concentration predicts outcome in inflammatory bowel disease after induction therapy with TNFalpha blocking agents. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18:2011–7. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos M, Dewit O, D’Haens G, et al. Fast and sharp decrease in calprotectin predicts remission by infliximab in anti-TNF naive patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:557–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vos MD, Louis EJ, Jahnsen J, et al. Consecutive Fecal Calprotectin Measurements to Predict Relapse in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Receiving Infliximab Maintenance Therapy. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2013;19:2111–2117. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829b2a37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) compared to 2. 4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND I trial. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;21:827–34. doi: 10.1155/2007/862917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine at 4. 8 g/day (800 mg tablet) for the treatment of moderately active ulcerative colitis: the ASCEND II trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;100:2478–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4. 8 g/day (800-mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1934, 43 e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein GR, Ramsey D, Rubin DT. Randomised clinical trial: delayed-release oral mesalazine 4.8 g/day vs. 2. 4 g/day in endoscopic mucosal healing--ASCEND I and II combined analysis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2011;33:672–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, et al. MMX mesalazine for the induction of remission of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: efficacy and tolerability in specific patient subpopulations. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2008;27:1094–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Sandborn WJ, et al. Effect of extended MMX mesalamine therapy for acute, mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15:1–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, et al. The role of centralized reading of endoscopy in a randomized controlled trial of mesalamine for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:149–157. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feagan BG, Chande N, Macdonald JK. Are There Any Differences in the Efficacy and Safety of Different Formulations of Oral 5-ASA Used for Induction and Maintenance of Remission in Ulcerative Colitis? Evidence from Cochrane Reviews Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2013;19:2031–40. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182920108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.