Abstract

Osteoporosis is a health concern characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and increased risk of fragility fractures. Many studies have investigated the association between genetic variants and osteoporosis. Polymorphism and allelic variations in the vitamin D receptor gene (VDR) have been found to be associated with bone mineral density. However, many studies have not been able to find this association. Literature review was conducted in several databases, including MEDLINE/Pubmed, Scopus, EMBASE, Ebsco, Science Citation Index Expanded, Ovid, Google Scholar, Iran Medex, Magiran and Scientific Information Database (SID) for papers published between 2000 and 2013 describing the association between Fok1 and Bsm1 polymorphisms of the VDR gene and osteoporosis risk. The majority of the revealed papers were conducted on postmenopausal women. Also, more than 50% studies reported significant relation between Fok1, Bsm1 and osteoporosis. Larger and more rigorous analytical studies with consideration of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions are needed to further dissect the mechanisms by which VDR polymorphisms influence osteoporosis.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Vitamin D receptor gene, Bone density, Polymorphism, Fok1, Bsm1

Introduction

The genetic variants of osteoporosis

Bone is a metabolically active tissue that experiences continuous remodeling via two reciprocal processes, bone formation and resorption. Respectively, osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes are responsible for bone resorption, formation and maintenance [1]. Osteoporosis is a bone disease characterized by low bone density caused by increased activity of osteoclasts and decreased bone turnover [2,3].

The prevalence of osteoporosis varies between different populations and ethnic groups [4-6] for example because of the high degree of ethnic variety in China, different studies show variety prevalence of osteoporosis [7-24]. Considering its high prevalence, the disease imposes a heavy burden on the patients and families as well as the healthcare system. In fact, the numbers of women with osteoporotic fractures are higher than those who experience breast, ovary and uterus cancer [25-27].

Osteoporosis is a disease caused by the interaction of genetic and environmental factors. According to many studies, the contribution of genetic and environmental factors is about 70% and 30% respectively. The environmental factors can control gene expression and accordingly, the process of the disease [28]. The study showed that 60-80% feature of bone mass depends on genetics. The Caucasians and Asians usually have lower bone density values than Negros, Hispanics and Latino Americans [29]. In addition, studies have shown that female offspring of osteoporotic women have lower bone density in comparison with that of those with normal bone density values [30]. Similarly, male offspring of men who are diagnosed with idiopathic osteoporosis have lower BMD in comparison with that of men with normal bone density values [31]. Also, the study of female twins have shown heritability of BMD to be 57% to 92% [32-35]. Different approaches including linkage studies on human and experimental animals as well as candidate gene studies and alterations in gene expression are being used currently to identify the role of genes in this regard [36].

There are many relevant published studies of the genetic susceptibility to osteoporosis. Genes can affect the skeletal system in two ways. The first, control body uptakes and intakes such as urinary calcium excretion to modulate BMD, the second way is poor metabolism due to genetic defects [37].

There calcium absorption pathways consists of trans_cellular and para_cellular. The trans_cellular pathway closely depends on the action of calcitriol and the intestinal vitamin D receptor. Transcellular transport occurs primarily in the duodenum where the VDR (Vitamin D receptor) is expressed in the highest concentration. So the regulation of VDR gene is most important in high efficiency of calcium absorption [38,39].

Estrogens are known to play an important role in regulating bone homeostasis and preventing postmenopausal bone loss. They act through binding to two different estrogen receptors (ERs), ERα and ERβ, which are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. Both ER kinds are expressed in osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and bone marrow stromal cells. And also ESRα has a prominent role in regulating bone turnover and the maintenance of bone mass [40,41].

Different studies have reported a list of effective genes on osteoporosis; the most important of which are vitamin D receptor gene(VDR), estrogen receptor alpha (ESRα) ,interleukin -6 (IL-6), Collagen type I (COLIA1), LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) [26,42,43].

Over the recent decades, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have contributed to the understanding of gene structure in complex and chronic diseases such as osteoporosis. Some of studies have indicated 62 significant loci where control bone mineral density variation [27,44-47].

Candidate genes for BMD

Candidate gene studies have mainly focused on Vitamin D receptor genes (VDR), type 1 Estrogen receptor genes (ESR1) and type 1 Collagen (Coli1) [41,48-50]. In this paper, the more important candidate genes, “VDR,” is discussed.

Vitamin D receptor gene

Vitamin D receptor’s (VDR) genotypes have been associated with the development of several bone diseases as well as multiple sclerosis (MS), osteoporosis, and vitamin D-dependent rickets type II and other complex maladies [51].

The human gene encoding the VDR gene has been localized on chromosome 12q12-q14. Vitamin D receptors (VDRs) are members of the NR1I family, which also includes pregnane X (PXR) and constitutive androstane (CAR) receptors, which form heterodimers with members of the retinoid X receptor family [52]. VDR is expressed in the intestine, thyroid and kidney and has a vital role in calcium homeostasis. VDRs repress the expression of 1-alpha-hydroxylase (the proximal activator of 1,25(OH)2D3) and induce the expression of 1,25(OH)2D3 through inactivating the enzyme CYP24. Also, it has recently been identified as an additional bile acid receptor alongside FXR with a protective role in gut against the toxic and carcinogenic effects of these endobiotics [53].

Gene ontology (GO) annotations related to this gene include steroid hormone receptor activity and sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity. An important paralog of this gene is NR4A3 [54].

There are more that 100 restriction endonuclease recognition sites in VDR gene and some of them are polymorphisms such as Fok1, Bsm1, Apa1 and …. .

Fok1 and Taq1 are located in exon 2 and 9 respectively. And also, Bsm1 and Apa1 are located in intron 8. Bsm1, Apa1 and Taq1 have been identified at the 3’ end of the gene. The effects of VDR gene polymorphisms are in connection with each other [55-57]. In many studies, polymorphisms of VDR gene have been investigated. A relationship between the VDR polymorphism and osteoporosis remain unclear requiring further in depth studies [58,59].

A series of characterized VDR gene polymorphisms, including Fok1, Bsm1, Taq1, and Apa1, have been extensively studied with regard to their association with osteoporosis, but with vise versa results [41,60-63].

Significant associations of Fok1 polymorphism with low BMD have been described in some studies, [64-66] but not in others [67,68].

The Bsm1 restriction enzyme identifies a polymorphic site at an intron at the 3′-end which is in linkage disequilibrium with several other polymorphisms, including Apa1, Taq1, and the variable-length poly(A) [69]. Although functional data have been inconclusive for Bsm1, several small studies evaluating Bsm1 have reported significant associations with osteoporosis [70,71].

To clear the relationship between osteoporosis and VDR gene polymorphisms (Fok1, Bsm1), we review the current evidence systematically.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

In this systematic review, the studies that had assessed the association between VDR gene polymorphisms and osteoporosis between 2000 and 2013 were included. In all these studies the diagnosis of osteoporosis was performed based on BMD measurement by Dual X-ray Densitometry (DXA) at least one of the bone sites. All kinds of original studies such as cross-sectional, longitudinal, and case controls were included. All review articles, Meta-analysis and systematic reviews after checking references (to avoid missing any paper), were excluded. Also, the articles performed on patients with secondary osteoporosis as well as non-human studies (cell culture or animal studies) and cellular-molecular discussions were excluded. To avoid language bias non-English-language publications were also included and Google-Translator was used to extract these articles’ data.

Literature search and data extraction

The search strategy was based on electronic and hand searching. Main key words in this systematic review were Osteoporosis, Bone density, vitamin D receptor gene, polymorphisms, Fok1 and Bsm1. We searched electronic databases of biological and health sciences including MEDLINE (pubmed), Scopus, EMBASE, Ebsco, Science Citation Index Expanded, Ovid, Google Scholar, Iran Medex, Magiran and Scientific Information Database (SID). All national and international congresses about genetic and osteoporosis like IOF and NOF congresses were examined. And also expert’s curriculum vitae in this field were checked for relevant studies. Subsequently, the searches were carried out and publications of interest were selected, based on titles and abstracts. The full text of all selected publications was assessed for relevance. If the full texts of papers were not available, they were obtained through correspondence with the authors. This was followed by extracting the relevant data from the identified publications according to the steps described in detail below. Totally, two reviewers reviewed the articles. In case of disagreement, the third reviewer assessed the articles.

The following data were extracted from each published article: name of the first author, publication year, the number of case and control by gender, the number of menopausal women, and the number of performed BMDs, ethnic origin of the studied population, mean age, genotyping method (PCR-RFLP and TaqMan), Bone sites, and the genotype frequency of the polymorphisms. The reliability of data extraction forms was assessed by genetics and endocrinology specialists. And the content validity was assessed by 10 articles and was confirmed by 0.75 Cronbach’s Alpha. Methodological quality, the strength and weaknesses of included studies were investigated using a modified STROBE checklist.

Results and discussion

Baseline characteristics

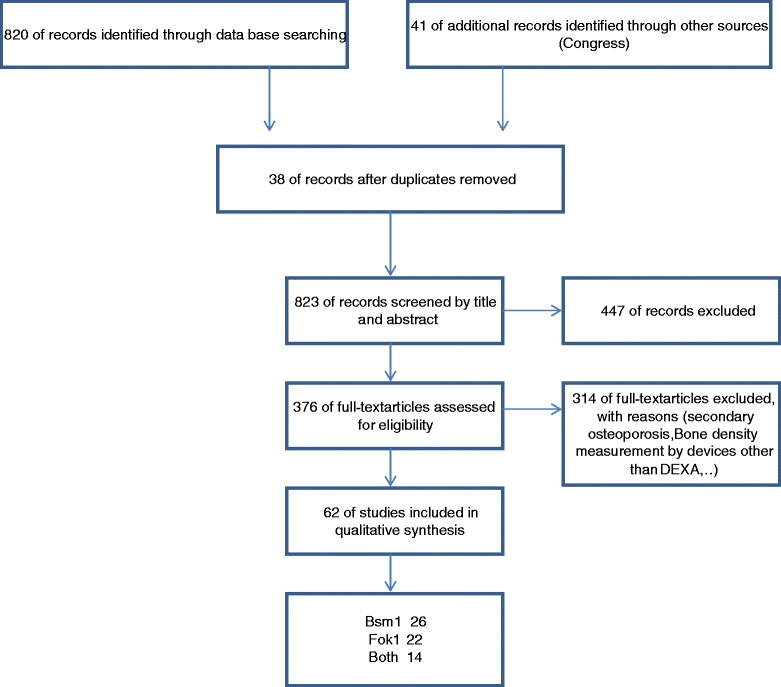

A schematic of the literature search is shown in Figure 1. According to the inclusion/exclusion criteria eligibility, 61 articles were identified regarding the associations between the Fok1 and Bsm1 polymorphisms of VDR gene and osteoporosis risk. Among these studies, 21 studies concerned the association of the Fok1 polymorphism with osteoporosis [9,72-91], while 26 studies investigated the association between Bsm1polymorphism and osteoporosis risk [92-117]. Also 14 articles evaluated both polymorphism associations with osteoporosis [118-131]. All of these 61 studies provided sufficient data to calculate the possible relationship between the two polymorphisms of the VDR gene and osteoporosis risk. The general characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| First author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Genotyping method | Design | Total sample size | Osteoporosis | Control | SNPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Wynne, F [72] | 2002 | Ireland | Irish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 511 | 381 | 130 | Fok1 |

| 2. | Van Pottelbergh [73] | 2002 | Belgium | Belgium | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 408 | 271 | 137 | Fok1 |

| 3. | Tarner [74] | 2012 | Turkey | Turkish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 229 | 183 | 46 | Fok1 |

| 4. | Jakubowska [75] | 2012 | Netherlands | Netherlands | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 455 | 161 | 294 | Fok1 |

| 5. | Kanan [76] | 2013 | Jordan | Jordanian | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 210 | 120 | 90 | Fok1 |

| 6. | Zhang [77] | 2006 | Chinese | Chinese | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 92 | 26 | 66 | Fok1 |

| 7. | Kim, J. G [78] | 2001 | Korea | Korean | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 229 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 8. | Deng, H. W [79] | 2002 | USA | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 630 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 9. | Lau, E. M. C [9] | 2002 | Chinese | Chinese | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 684 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 10. | Chen,H . Y [80] | 2002 | Taiwan | Taiwan | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 163 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 11. | Strandberg, S. [81] | 2003 | Sweden | Swedish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 88 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 12. | Rabon-stith,K. M [82] | 2005 | USA | USA (Maryland) | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 206 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 13. | Cusack, S. [83] | 2006 | Denmark | Danish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 224 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 14. | Terpstra [84] | 2006 | Netherlands | Netherlands | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 120 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 15. | Lau, H. H. L [85] | 2006 | Chinese | southern Chinese | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 674 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 16. | Falchetti, A. [86] | 2007 | Italy | Lampedusa (Italian) | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 424 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 17. | Han, X. [87] | 2009 | Chinese | Han | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 100 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 18. | Hosseinnejad [88] | 2009 | IRAN | IRAN | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 205 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 19. | Hosseinnejad [89] | 2009 | IRAN | IRAN | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 312 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 20. | Ozaydin [90] | 2010 | Turkey | Turkish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 88 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 21. | Galbav [91] | 2010 | Slovakia | Slovak | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 121 | - | - | Fok1 |

| 22. | Perez, A. [92] | 2008 | Argentina | Cordoba | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 176 | 108 | 68 | Bsm1 |

| 23. | Fontova, R. [93] | 2000 | Spain | Spanish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 156 | 105 | 51 | Bsm1 |

| 24. | Uysal, A, R. [94] | 2008 | Turkey | Turkish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 246 | 100 | 146 | Bsm1 |

| 25. | Eckstein [95] | 2002 | Israeli | Jewish Israeli | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 324 | 86 | 238 | Bsm1 |

| 26. | Borjas-Fajardo. L [96] | 2003 | Spain | Spanish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 133 | 78 | 55 | Bsm1 |

| 27. | DurusuTanriover, M. [97] | 2010 | Turkey | Turkish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 100 | 50 | 50 | Bsm1 |

| 28. | Chen, J. [98] | 2003 | Chinese | Chinese | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 61 | 40 | 21 | Bsm1 |

| 29. | Tamulaitien [99] | 2012 | Lithuania | Lithuania | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 73 | 28 | 45 | Bsm1 |

| 30. | Nelson [100] | 2000 | USA | African-American | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 43 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 31. | Sowinska [101] | 2000 | Poland | Polish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 88 | 40 | 48 | Bsm1 |

| 32. | Chen,H.Y [102] | 2001 | Chinese | Chinese | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 171 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 33. | Pollak, R. D [103] | 2001 | Israeli | Israelis | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 634 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 34. | Kubota, M [104] | 2001 | Japan | Japanese | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 126 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 35. | Laaksonen, M. [105] | 2002 | Finland | Finish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 93 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 36. | van der Sluis, I. M. [106] | 2003 | Netherlands | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 148 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 37. | Grundberg [107] | 2003 | Sweden | Swedish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 343 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 38. | Kammerer, C. M. [108] | 2004 | Mexico | Mexican American | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 471 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 39. | Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, A [132] | 2004 | Poland | Polish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 34 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 40. | Palomba, S. [110] | 2005 | Italy | Italian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 1100 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 41. | Dong, J. [111] | 2006 | Chinese | Han | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 90 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 42. | Bernardes[112] | 2005 | Portugal | Portuguese | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 114 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 43. | Mitra, S. [113] | 2006 | India | Indian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 246 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 44. | Bezerra [114] | 2008 | Brazil | Brazilian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 40 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 45. | Musumeci [115] | 2009 | Italy | Sicilian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 360 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 46. | Stathopoulou, M. G. [116] | 2011 | Greece | Greece | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 578 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 47. | Pouresmaeili [117] | 2013 | IRAN | IRAN | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 146 | - | - | Bsm1 |

| 48. | Horst -Sikorska, W. [118] | 2007 | Poland | Polish | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 279 | - | - | Both |

| 49. | Gonzalez [119] | 2013 | Mexico | Mexican-Mestizo | TaqMan | Case-Control | 320 | 232 | 88 | Both |

| 50. | Kanan, R. M. [120] | 2008 | Jordan | Jordanian | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 230 | 150 | 80 | Both |

| 51. | Lisker, R [121] | 2003 | Mexico | Mexican | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 122 | 65 | 57 | Both |

| 52. | Mansour, L. [122] | 2010 | Egypt | Egyptian | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 70 | 50 | 20 | Both |

| 53. | Rogers [123] | 2000 | no indicated | no indicated | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 46 | Both | ||

| 54. | Lorentzon [124] | 2001 | Sweden | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 99 | - | - | Both |

| 55. | Zajíčková [125] | 2002 | Czech | Czech | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 114 | - | - | Both |

| 56. | Vidal, C. [126] | 2003 | Malta | Malta | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 104 | - | - | Both |

| 57. | Bandrés [127] | 2005 | Spain | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 177 | - | - | Both |

| 58. | Ivanova, J. [128] | 2006 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 219 | - | - | Both |

| 59. | Macdonald, H. M [129] | 2006 | UK | Scotland | PCR-RFLP | Cross-sectional | 3100 | - | - | Both |

| 60. | Yavuz [130] | 2007 | Turkey | Turkish | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 206 | 381 | 130 | Both |

| 61. | Sanwalka [131] | 2013 | India | Indian | PCR-RFLP | Case-Control | 120 | 271 | 137 | Both |

In these studies, diverse groups of people were discussed. 36.5% of the studies studied postmenopausal women. On the other hand, post-menopausal and pre-menopausal woman were studied simultaneously in 22.2% of the articles and 12.7% of them studied all groups.

According to the results, 96.8% of studies performed the polymorphisms using PCR-RFLP “polymerase chain reaction- restriction fragment length polymorphism”. The other methods such as Taq-man were used to determine the association between Bsm1 and Fok1 polymorphisms and osteoporosis.

As mentioned above, the studies after year 2000 on world were enrolled in this systematic review. Most articles were published in 2006 and after that the number of papers showed a decline trend.

Based on articles, totally 17473 persons studied. 65.9% of studies reported a significant relation between Bsm1 and osteoporosis risk. Likewise, 60.0% of studies reported a significant relation between Fok1 and osteoporosis risk.

Also, the papers were categorized by gender and age. The data indicated that most of the articles were done on women and also on older ages. Most of studies were examined post menopausal women.

After characterization of authors” countries, it was demonstrated that respectively china [9,77,85,87,98,102] and Turkey [74,90,94,97,130] presented 6 and 5 studies and identified as most active countries in such researches.

In conclusion, both gender and ethnicity are effective factor on osteoporosis and bone mineral density.

As is evident, genetic variant has a tremendous roll to adjust bone activities and therefore along with vitamin D deficiency, has a large effect on osteoporosis incidence and also osteoporotic fractures. In this systematic review, due to study the association between low bone density and Bsm1 and Fok1 polymorphisms, 61 papers were studied and statistically analyzed. As a main result, most of the studies were performed on post-menopausal women i.e. the largest risk group to their major content of research [132]. It seems that it is necessary to evaluate the association of genetic variant for lower age groups of both genders. Accordingly, genetic testing can be used to prevent osteoporosis and low bone density.

In more than 50% of studies a significant association was found between the two polymorphisms (Fok1 and Bsm1) and osteoporosis. Based on the articles, 65.9% of studies reported a significant correlation between Bsm1 and osteoporosis risk. Likewise, 60.0% of studies reported a significant correlation between Fok1 and osteoporosis risk. Most of the studies were performed in developed countries but also, developing countries have initiated this way.

An important and noticeable issue in this systematic review is different results in different races [44,133]. Ethnicity and race, like gender, can influence the epidemiology of osteoporosis and BMD. Some of studies indicate that lowest BMD shown in white women and also, bone mineral density is higher in African Americans [134,135].

In more that 95% studies for assessing polymorphisms, PCR-RFLP were used (Table 1). It is noteworthy; Taq-Man is approximately novel methods which used [119].

Conclusion

In summary, there is large ethnic and racial variability in BMD levels and osteoporosis rates. Across all racial groups and polymorphisms differences, women experience osteoporosis is more than the combined number of women who experience breast cancer. Prevention efforts should target all women, irrespective of their race and ethnicity, especially if they have multiple risk factors. And also, using novel and pioneer genetic techniques to better assess and better quality can be useful.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

This Article comes from Thesis. Obviously, to provide a systematic review, according to the standards, several experts should participate to review the articles and two different persons should check the excluded data, and a third reviewer should recheck all of these procedures. All authors contributed in these steps. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Zahra Mohammadi, Email: mimina_13@yahoo.com.

Fateme Fayyazbakhsh, Email: f.fba.te@gmail.com.

Mehdi Ebrahimi, Email: m_ebrahimi49@yahoo.com.

Mahsa M Amoli, Email: Mahsaamoli@hotmail.com.

Patricia Khashayar, Email: patricia.kh@gmail.com.

Mahboubeh Dini, Email: drmahdin@yahoo.com.

Reza Nezam Zadeh, Email: nezamzadeh@yahoo.com.

Abbasali Keshtkar, Email: abkeshtkar@yahoo.com.

Hamid Reza Barikani, Email: hr_barikani@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Manolagas SC. Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis 1. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:115–137. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes by glucocorticoids. Potential mechanisms of their deleterious effects on bone. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:274. doi: 10.1172/JCI2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison NA, Qi JC, Tokita A, Kelly PJ, Crofts L, Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Prediction of bone density from vitamin D receptor alleles. Nature. 1994;367:284–287. doi: 10.1038/367284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett‐Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, Miller PD, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:185–194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, Lindsay RL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older US adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1761–1768. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faucki A, Eugene B, Dennis L, Stephen L, Dan L, Jameson J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, Vol II. 17. United States, New York: McGrow-Hill Medical; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Tao G, Wu Q, Liu J, Gao Y, Chen R, Leng X. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in postmenopausal women of the Han and Uygur nationalities in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000;113:787–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambrinoudaki I, Kung AWC. Absence of high-risk “s” allele associated with osteoporosis at the intronic SP1 binding-site of collagen Iα1 gene in Southern Chinese. J Endocrinol Investig. 2001;24:499–502. doi: 10.1007/BF03343882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau EMC, Lam V, Li M, Ho K, Woo J. Vitamin D receptor start codon polymorphism (Fok I) and bone mineral density in Chinese men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:218–221. doi: 10.1007/s001980200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, Meng X, Zhou X, Xing X, Yu W. Association of parathyroid hormone gene polymorphism with bone mineral density in Chinese women. Chin Med Sci J. 2003;18:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang DK, Shen H, Li MX, Jiang C, Yang N, Zhu J, Wu Y, Qin YJ, Zhou Q, Deng HW. No major effect of the insulin-like growth factor I gene on bone mineral density in premenopausal Chinese women. Bone. 2005;36:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YB, Guo JJ, Liu YJ, Deng FY, Jiang DK, Deng HW. The Human Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Interleukin-6 Genes are Associated with Bone Mineral Density in Chinese. Acta Genetica Sin. 2006;33:870–880. doi: 10.1016/S0379-4172(06)60121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong X, Hsu YH, Terwedow H, Tang G, Liu X, Jiang S, Xu X. Association of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and fracture risk in Chinese postmenopausal women. Bone. 2007;40:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang DK, Xu FX, Liu MY, Chen XD, Li MX, Liu YJ, Shen H, Deng HW. No evidence of association of the osteocalcin gene HindIII polymorphism with bone mineral density in Chinese women. JMNI. 2007;7:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung CL, Huang QY, Chan V, Kung AWC. Association of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) promoter SNP with peak bone mineral density in Chinese women. Hum Hered. 2008;65:232–239. doi: 10.1159/000112370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JT, Guo Y, Yang TL, Xu XH, Dong SS, Li M, Li TQ, Chen Y, Deng HW. Polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor genes are associated with hip fractures in Chinese. Bone. 2008;43:910–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou B, Wang XH, Wang ST, Guo LY, Xu C, Zhang Z, Kan ZY. Gene polymorphism in Cdx-2 binding sites of the vitamin D receptor and bone loss in the elderly in China. J Clin Rehab Tissue Eng Res. 2008;12:9130–9133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang QY, Li GHY, Kung AWC. Multiple osteoporosis susceptibility genes on chromosome 1p36 in Chinese. Bone. 2009;44:984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu JM, Zhang MJ, Zhao L, Cui B, Li ZB, Zhao HY, Sun LH, Tao B, Li M, Ning G. Analysis of recently identified osteoporosis susceptibility genes in Han Chinese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;95:E112–E120. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong TYY, Yong RYY, Goh VHH, Liang S, Chong APL, Mok HPP, Yong EL, Yap EPH, Moochhala S. Association between an intronic apolipoprotein E polymorphism and bone mineral density in Singaporean Chinese females. Bone. 2010;47:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng FY, Lei SF, Chen XD, Tan LJ, Zhu XZ, Deng HW. An integrative study ascertained SOD2 as a susceptibility gene for osteoporosis in Chinese. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2695–2701. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu WW, He JW, Zhang H, Wang C, Gu JM, Yue H, Ke YH, Hu YQ, Fu WZ, Li M, Liu YJ, Zhang ZL. No association between polymorphisms and haplotypes of COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes and osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal Chinese women. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:947–955. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li HYG, Kung WCA, Huang QY. Bone mineral density is linked to 1p36 and 7p15-13 in a southern Chinese population. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29:80–87. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Xi B, Li K, Wang C. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and bone mineral density in Chinese women. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:5709–5717. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ, Podgornik MN. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2005;2007(385):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hustmyer FG, Peacock M, Hui S, Johnston C, Christian J. Bone mineral density in relation to polymorphism at the vitamin D receptor gene locus. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2130. doi: 10.1172/JCI117568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burge R. Dawson‐Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis‐related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari S. Osteoporosis: a Complex Disorder of Aging with Multiple Genetic and Environmental Determinants. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labinson P, Taxel P, Gagel RF, Hoff AO. National Osteoporosis Foundation. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Leeuwen JP, Uitterlinden AG, Birkenhäger JC, Pols HA. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and osteoporosis. Steroids. 1996;61:154–156. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(96)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Pottelbergh I, Goemaere S, Zmierczak H, De Bacquer D, Kaufman J. Deficient Acquisition of Bone During Maturation Underlies Idiopathic Osteoporosis in Men: Evidence From a Three‐Generation Family Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:303–311. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slemenda CW, Christian JC, Williams CJ, Norton JA, Johnston CC. Genetic determinants of bone mass in adult women: a reevaluation of the twin model and the potential importance of gene interaction on heritability estimates. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:561–567. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen T, Howard G, Kelly P, Eisman JA. Bone mass, lean mass, and fat mass: same genes or same environments? Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:3–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris M, Nguyen T, Howard G, Kelly P, Eisman J. Genetic and environmental correlations between bone formation and bone mineral density: a twin study. Bone. 1998;22:141–145. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL, Yeates MG, Sambrook PN, Eberl S. Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults. A twin study. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:706. doi: 10.1172/JCI113125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams F, Spector T. Recent advances in the genetics of osteoporosis. JMNI. 2006;6:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng HW, Chen WM, Recker S, Stegman MR, Li JL, Davies KM, Zhou Y, Deng H, Heaney R, Recker RR. Genetic determination of Colles’ fracture and differential bone mass in women with and without Colles’ fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1243–1252. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.7.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X-Q, Tembe V, Horwitz GM, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ. Increased intestinal vitamin D receptor in genetic hypercalciuric rats. A cause of intestinal calcium hyperabsorption. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:661. doi: 10.1172/JCI116246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xue Y, Fleet JC. Intestinal vitamin D receptor is required for normal calcium and bone metabolism in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1317–1327. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bland R. Steroid hormone receptor expression and action in bone. Clin Sci. 2000;98:217–240. doi: 10.1042/cs0980217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gennari L, Merlotti D, De Paola V, Calabro A, Becherini L, Martini G, Nuti R. Estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and the genetics of osteoporosis: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:307–320. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandi ML, Gennari L, Cerinic MM, Becherini L, Falchetti A, Masi L, Gennari C, Reginster J-Y. Genetic markers of osteoarticular disorders: facts and hopes. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:270–280. doi: 10.1186/ar316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison NA, Yeoman R, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA. Contribution of trans-acting factor alleles to normal physiological variability: vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and circulating osteocalcin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:6665–6669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peacock M, Turner CH, Econs MJ, Foroud T. Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:303–326. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardy J, Singleton A. Genomewide association studies and human disease. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:1759–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards J, Rivadeneira F, Inouye M, Pastinen T, Soranzo N, Wilson S, Andrew T, Falchi M, Gwilliam R, Ahmadi K. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and osteoporotic fractures: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2008;371:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60599-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richards JB, Zheng H-F, Spector TD. Genetics of osteoporosis from genome-wide association studies: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:576–588. doi: 10.1038/nrg3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ralston SH. Genetic control of susceptibility to osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2002;87:2460–2466. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ralston S. The genetics of osteoporosis. QJM. 1997;90:247–251. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood RJ, Fleet JC. The genetics of osteoporosis: vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Annu Rev Nutr. 1998;18:233–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.18.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nejentsev S, Godfrey L, Snook H, Rance H, Nutland S, Walker NM, Lam AC, Guja C, Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Undlien DE. Comparative high-resolution analysis of linkage disequilibrium and tag single nucleotide polymorphisms between populations in the vitamin D receptor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1633–1639. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahn J, Albanes D, Berndt SI, Peters U, Chatterjee N, Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Huang W-Y, Kibel AS, Crawford ED. Vitamin D-related genes, serum vitamin D concentrations, and prostate cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;2009:bgp055. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taymans SE, Pack S, Pak E, Orban Z, Barsony J, Zhuang Z, Stratakis CA. The Human Vitamin D Receptor Gene (VDR) Is Localized to Region 12cen‐q12 by Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization and Radiation Hybrid Mapping: Genetic and Physical VDR Map. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1163–1166. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bai Y, Yu Y, Yu B, Ge J, Ji J, Lu H, Wei J, Weng Z, Tao Z, Lu J. Association of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms with the risk of prostate cancer in the Han population of Southern China. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferrari S, Rizzoli R, Chevalley T, Eisman J, Bonjour J, Slosman D. Vitamin-D-receptor-gene polymorphisms and change in lumbar-spine bone mineral density. Lancet. 1995;345:423–424. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shahbazi S, Alavi S, Majidzadeh-A K, GhaffarPour M, Soleimani A, Mahdian R. BsmI but not FokI polymorphism of VDR gene is contributed in breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naito M, Miyaki K, Naito T, Zhang L, Hoshi K, Hara A, Masaki K, Tohyama S, Muramatsu M, Hamajima N. Association between vitamin D receptor gene haplotypes and chronic periodontitis among Japanese men. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:216. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown MA, Duncan EL. Genetic studies of osteoporosis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 1999;1:1–18. doi: 10.1586/17434440.1.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abbasi M, Hasani S, Sheikholeslami H, Alizadeh S, Rashvand Z, Yazdi Z, Najafipour R. Association between Vitamin D receptor Apa1 and Taq1 Genes Polymorphism and Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences. 2012;16:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thakkinstian A, D’Este C, Attia J. Haplotype analysis of VDR gene polymorphisms: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:729–734. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1601-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riggs LB, Nguyen TV, Melton JL, Morrison NA, O’Fallon WM, Kelly PJ, Egan KS, Sambrook PN, Muhs JM, Eisman JA. The contribution of vitamin D receptor gene alleles to the determination of bone mineral density in normal and osteoporotic women. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:991–996. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eisman JA. Vitamin D, receptor gene alleles and osteoporosis: an affirmative view. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1289–1293. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arai H, Miyamoto KI, Taketani Y, Yamamoto H, Iemori Y, Morita K, Tonai T, Nishisho T, Mori S, Takeda E. A vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in the translation initiation codon: effect on protein activity and relation to bone mineral density in Japanese women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:915–921. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris SS, Eccleshall T, Gross C. Dawson‐Hughes B, Feldman D. The vitamin D receptor start codon polymorphism (FokI) and bone mineral density in premenopausal American black and white women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1043–1048. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gross C, Eccleshall TR, Malloy PJ, Villa ML, Marcus R, Feldman D. The presence of a polymorphism at the translation initiation site of the vitamin D receptor gene is associated with low bone mineral density in postmenopausal mexican‐American women. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1850–1855. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferrari S, Rizzoli R, Manen D, Slosman D, Bonjour JP. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Start Codon Polymorphisms (FokI) and Bone Mineral Density: Interaction with Age, Dietary Calcium, and 3′‐End Region Polymorphisms. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:925–930. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eccleshall TR, Garnero P, Gross C, Delmas PD, Feldman D. Lack of correlation between start codon polymorphism of the vitamin D receptor gene and bone mineral density in premenopausal French women: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:31–35. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ingles SA, Haile RW, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN, Nakaichi G, Shi C-Y, Yu MC, Ross RK, Coetzee GA. Strength of linkage disequilibrium between two vitamin D receptor markers in five ethnic groups: implications for association studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barr R, Macdonald H, Stewart A, McGuigan F, Rogers A, Eastell R, Felsenberg D, Glüer C, Roux C, Reid D. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, falls, balance and muscle power: results from two independent studies (APOSS and OPUS) Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:457–466. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ames SK, Ellis KJ, Gunn SK, Copeland KC, Abrams SA. Vitamin D receptor gene Fok1 polymorphism predicts calcium absorption and bone mineral density in children. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:740–746. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wynne F, Drummond F, O’Sullivan K, Daly M, Shanahan F, Molloy MG, Quane KA. Investigation of the genetic influence of the OPG, VDR (Fok1), and COLIA1 Sp1 polymorphisms on BMD in the Irish population. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71:26–35. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Pottelbergh I, Goemaere S, De Bacquer D, De Paepe A, Kaufman M. Vitamin D receptor gene allelic variants, bone density, and bone turnover in community-dwelling men. Bone. 2002;31:631–637. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tarner IH, Erkal MZ, Obermayer-Pietsch BM, Hofbauer LC, Bergmann S, Goettsch C, Madlener K, Muller-Ladner U, Lange U. Osteometabolic and osteogenetic pattern of Turkish immigrants in Germany. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:517–523. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jakubowska-Pietkiewicz E, Mlynarski W, Klich I, Fendler W, Chlebna-Sokol D. Vitamin D receptor gene variability as a factor influencing bone mineral density in pediatric patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:6243–6250. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1444-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanan RM. The effect of FokI vitamin D receptor polymorphism on bone mineral density in Jordanian perimenopausal women. Indian J Human Genet. 2013;19:233. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.116125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang HH, Hu YZ, Zhan ZW, Mu XF, Pei Y, Wu Q, Meng XM, Cui ZH, Tao GS. Relationship between vitamin D receptor gene (Fok 1) polymorphism and osteoporosis in the elderly men. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2006;10:153–155. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim JG, Lim KS, Kim EK, Choi YM, Lee JY. Association of vitamin D receptor and estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms with bone mass in postmenopausal Korean women. Menopause. 2001;8:222–228. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deng HW, Shen H, Xu FH, Deng HY, Conway T, Zhang HT, Recker RR. Tests of linkage and/or association of genes for vitamin D receptor, osteocalcin, and parathyroid hormone with bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:678–686. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen HY, Chen WC, Hsu CD, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH. Relation of vitamin D receptor FokI start codon polymorphism to bone mineral density and occurrence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in Taiwan. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Strandberg S, Nordström P, Lorentzon R, Lorentzon M. Vitamin D receptor start codon polymorphism (FokI) is related to bone mineral density in healthy adolescent boys. J Bone Miner Metab. 2003;21:109–113. doi: 10.1007/s007740300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rabon-Stith KM, Hagberg JM, Phares DA, Kostek MC, Delmonico MJ, Roth SM, Ferrell RE, Conway JM, Ryan AS, Hurley BF. Vitamin D receptor FokI genotype influences bone mineral density response to strength training, but not aerobic training. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:653–661. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cusack S, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF, Jakobsen J, Lamberg-Allardt CJE, Cashman KD. Vitamin D and estrogen receptor-α genotype and indices of bone mass and bone turnover in Danish girls. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Terpstra L, Knol D, Van Coeverden S, Delemarre‐van de Waal H. Bone metabolism markers predict increase in bone mass, height and sitting height during puberty depending on the VDR Fok1 genotype. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;64:625–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lau HH, Ng MY, Cheung WM, Paterson AD, Sham PC, Luk KD, Chan V, Kung AW. Assessment of linkage and association of 13 genetic loci with bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:226–234. doi: 10.1007/s00774-005-0676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Falchetti A, Sferrazza C, Cepollaro C, Gozzini A, Del Monte F, Masi L, Napoli N, Di Fede G, Cannone V, Cusumano G. FokI polymorphism of the vitamin D receptor gene correlates with parameters of bone mass and turnover in a female population of the Italian island of Lampedusa. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;80:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Han X, Zhan ZW, Zhang HH, Pei Y, Hu YZ, Wang XR, Han ZT. Association between vitamin D receptor genetypes of Fok I polymorphism and bone mineral density in male of the Han nationality in Beijing area. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 2009;13:4763–4766. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hossein-Nezhad A, Ahangari G, Behzadi H, Maghbooli Z, Larijani B. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism may predict response to vitamin D intake and bone turnover. Daru. 2009;17:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hossein-nezhad A, Ahangari G, Larijani B: Evaluating of VDR gene variation and its interaction with Immune Regulatory Molecules in Osteoporosis.Iranian J Public Health 2009, 27–36.

- 90.Ozaydin E, Dayangac-Erden D, Erdem-Yurter H, Derman O, Coskun T. The relationship between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and bone density, osteocalcin level and growth in adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;23:491–496. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2010.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Galbavý D, Omelka R, Bauerová M, Hunák O. ESR, CALCR and VDR gene polymorphisms and their relation to bone mineral density, bone turnover markers and incidence of fractures in Slovak osteoporotic women. Vzt’ah polymorfizmov v ESR, CALCR a VDR génoch k hustote kostného minerálu, markerom kostného obratu a výskytu fraktúr v populácii slovenských osteoporotických žien. 2010;15:156–164. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pérez A, Ulla M, García B, Lavezzo M, Elías E, Binci M, Rivoira M, Centeno V, Alisio A, De Talamoni NT. Genotypes and clinical aspects associated with bone mineral density in Argentine postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:358–365. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0840-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fontova Garrofé R, Gutiérrez Fornés C, Broch Montané M, Aguilar Crespillo C, Pujol Del Pozo A, Ortega JV, Jurado CR. Polymorphism of vitamin D receptor gene, bone mass, and bone turnover among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of Revista clinica espanola. 2000;200:198–202. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2565(00)70605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Uysal AR, Sahin M, Gursoy A, Gullu S. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and osteoporosis in the Turkish population. Genet Test. 2008;12:591–594. doi: 10.1089/gte.2008.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eckstein M, Vered I, Ish-Shalom S, Shlomo AB, Shtriker A, Koren-Morag N, Friedman E. Vitamin D and calcium-sensing receptor genotypes in men and premenopausal women with low bone mineral density. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:340–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Borjas-Fajardo L, Zambrano M, Fernández E, Pineda L, Machín A, De Romero P, Zabala W, Sánchez MA, Chacín JA, Delgado W. Analysis of Bsm I polymorphism of the Vitamin D receptor gen (VDR) in Venezuelan patients with osteoporosis. Análisis del polimorfismo Bsm I del gen receptor de la vitamina D (VDR) en pacientes venezolanas residentes del estado Zulia con osteoporosis. 2003;44:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Durusu Tanriover M, Bora Tatar G, Uluturk TD, Dayangac Erden D, Tanriover A, Kilicarslan A, Oz SG, Erdem Yurter H, Sozen T, Sain Guven G. Evaluation of the effects of vitamin D receptor and estrogen receptor 1 gene polymorphisms on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1285–1293. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen J, Zhang LP, Qiu JF, Peng H, Deng ZL, Wang YJ, Yan ZD. Studies on the relationship between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chinese Journal of Medical Genetics. 2003;20:167–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tamulaitienė M, Marozik P, Alekna V, Mosse I, Strazdienė A, Mastavičiūtė A, Rudenko E, Piličiauskienė R, Ameliyanovich M. Association of VDR BsmI gene polymorphism, bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in severe postmenopausal osteoporosis. Gerontologija. 2012;13:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nelson DA, Vande Vord PJ, Wooley PH. Polymorphism in the vitamin D receptor gene and bone mass in African-American and white mothers and children: a preliminary report. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:626–630. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.8.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sowińska-Przepiera E, Grys E. Polymorphism of vitamin D receptor Bsm I gene and of estrogen receptor Xba I and Pvu II gene in girls and women with low bone mass. Polimorfizm Bsm I genu receptora witaminy D oraz Xba I i Pvu II genu receptora estrogenow u dziewczat z niska masa kostna. 2000;71:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen HY, Chen WC, Hsu CD, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Li CW. Relation of BsmI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism to bone mineral density and occurrence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal Chinese women in Taiwan. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:1036–1041. doi: 10.1007/s001980170014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pollak RD, Blumenfeld A, Bejarano-Achache I, Idelson M, Hochner DC. The BsmI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in Israeli populations and in perimenopausal and osteoporotic Ashkenazi women. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:185–188. doi: 10.1159/000046245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kubota M, Yoshida S, Ikeda M, Okada Y, Arai H, Miyamoto K, Takeda E. Association between two types of vitamin d receptor gene polymorphism and bone status in premenopausal Japanese women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68:16–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02684998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Laaksonen M, Kärkkäinen M, Outila T, Vanninen T, Ray C, Lamberg-Allardt C. Vitamin D receptor gene BsmI-polymorphism in Finnish premenopausal and postmenopausal women: Its association with bone mineral density, markers of bone turnover, and intestinal calcium absorption, with adjustment for lifestyle factors. J Bone Miner Metab. 2002;20:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s007740200055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van der Sluis IM, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM, Krenning EP, Pols HA, Uitterlinden AG. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism predicts height and bone size, rather than bone density in children and young adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:332–338. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-2130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grundberg E, Brändström H, Ribom E, Ljunggren O, Kindmark A, Mallmin H. A poly adenosine repeat in the human vitamin D receptor gene is associated with bone mineral density in young Swedish women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-0032-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kammerer CM, Dualan AA, Samollow PB, Périssé ARS, Bauer RL, MacCluer JW, O'Leary DH, Mitchell BD. Bone mineral density, carotid artery intimal medial thickness, and the vitamin D receptor BsmI polymorphism in Mexican American women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75:292–298. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Seremak-Mrozikiewicz A, Drews K, Danska A, Spaczynski M, Opala T, Mrozikiewicz PM. Vitamin D receptor polymorphism in the group of postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. Ginekol Pol. 2004;75:367–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Palomba S, Numis FG, Mossetti G, Rendina D, Vuotto P, Russo T, Zullo F, Nappi C, Nunziata V. Raloxifene administration in post‐menopausal women with osteoporosis: effect of different BsmI vitamin D receptor genotypes. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:192–198. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dong J, Huang ZW, Piao JH, Gong J. Association of bone mineral density with gene polymorphisms and environmental factors in Chinese postmenopausal women. Wei sheng yan jiu =Journal of hygiene research. 2006;35:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bernardes M, Pires A, Bernardo A, Alves H, Simoes-Ventura F. Bone Mass in postmenopausal Portuguese Women: Interaction between BSMI Vitamin D Receptor gene and PVUII Estrogen Receptor Gene polymorphisms. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. London WC1H 9JR, England: BMJ Publishing Group British Med Assoc House, Tavistock Square; 2005. pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mitra S, Desai M, Ikram KM. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Indian women. Maturitas. 2006;55:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bezerra FF, Cabello GM, Mendonca LM, Donangelo CM. Bone mass and breast milk calcium concentration are associated with vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in adolescent mothers. J Nutr. 2008;138:277–281. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Musumeci M, Vadalà G, Tringali G, Insirello E, Roccazzello AM, Simpore J, Musumeci S. Genetic and environmental factors in human osteoporosis from Sub-Saharan to Mediterranean areas. J Bone Miner Metab. 2009;27:424–434. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stathopoulou MG, Dedoussis GV, Trovas G, Theodoraki EV, Katsalira A, Dontas IA, Hammond N, Deloukas P, Lyritis GP. The role of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in the bone mineral density of Greek postmenopausal women with low calcium intake. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:752–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pouresmaeili F, Jamshidi J, Azargashb E, Samangouee S. Association between vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphism and bone mineral density in a population of 146 Iranian women. Cell J. 2013;15:75–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Horst-Sikorska W, Kalak R, Wawrzyniak A, Marcinkowska M, Celczynska-Bajew L, Slomski R. Association analysis of the polymorphisms of the VDR gene with bone mineral density and the occurrence of fractures. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:310–319. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gonzalez-Mercado A, Sanchez-Lopez JY, Regla-Nava JA, Gamez-Nava JI, Gonzalez-Lopez L, Duran-Gonzalez J, Celis A, Perea-Diaz FJ, Salazar-Paramo M, Ibarra B. Association analysis of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Mexican-Mestizo women. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:2755–2763. doi: 10.4238/2013.July.30.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kanan RM, Mesmar M. The effect of vitamin D receptor and estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms on bone mineral density in healthy and osteoporotic postmenopausal Jordanian women. Int J Integr Biol. 2008;4:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lisker R, López MA, Jasqui S, De León Rosales SP, Correa-Rotter R, Sánchez S, Mutchinick OM. Association of Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms with osteoporosis in Mexican postmenopausal women. Hum Biol. 2003;75:399–403. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mansour L, Sedky M, AbdelKhader M, Sabry R, Kamal M, El-Sawah H. The role of vitamin D receptor genes (FOKI and BSMI) polymorphism in osteoporosis. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2010;15:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2010.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rogers A, Hannon R, Lambert H, Barker M, Sorrell J, Eastell R. A novel approach to examining VDR polymorphisms (BsmI and Fokl) and the risk of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:488. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lorentzon M, Lorentzon R, Nordstrom P. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is related to bone density, circulating osteocalcin, and parathyroid hormone in healthy adolescent girls. J Bone Miner Metab. 2001;19:302–307. doi: 10.1007/s007740170014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zajíčková K, Žofková I. Polymorphisms in osteoporosis-related candidate genes and their associations not only with bone metabolism. Polymorfizmy v kandidátních genech pro osteoporózu a jejich asociace nejen s kostním metabolismem. 2007;10:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vidal C, Grima C, Brincat M, Megally N, Xuereb-Anastasi A. Associations of polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene (Bsml and Fokl) with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women in Malta. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:923–928. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bandrés E, Pombo I, González-Huarriz M, Rebollo A, López G, García-Foncillas J. Association between bone mineral density and polymorphisms of the VDR, ERα, COL1A1 and CTR genes in Spanish postmenopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:312–321. doi: 10.1007/BF03347196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ivanova J, Doukova P, Boyanov M, Popivanov P. FokI and BsmI polymorphisms of the vitamin D receptor gene and bone mineral density in a random Bulgarian population sample. Endocrine. 2006;29:413–418. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:3:413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Macdonald HM, McGuigan FE, Stewart A, Black AJ, Fraser WD, Ralston S, Reid DM. Large-scale population-based study shows no evidence of association between common polymorphism of the VDR gene and BMD in British women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:151–162. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yavuz DG, Yuksel M, Tarcin O, Yazici D, Telli A, Sancak S, Deyneli O, Aydin H, Haklar G, Akalin S. Vitamin D receptor Gene Bsm1 and Fok1 Polymorphisms and Indices of Bone Mass and Bone Turnover in Healty young Turkish Men and Women. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sanwalka N, Khadilkar A, Chiplonkar S, Khatod K, Phadke N, Khadilkar V. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and bone mass indices in post-menarchal Indian adolescent girls. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31:108–115. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Organization WH . Assessment of Fracture Risk and its Application to Screening for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: Report of a WHO Study Group [Meeting Held in Rome from 22 to 25 June 1992] 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Anderson JJ, Pollitzer WS. Ethnic and Genetic Differences in Susceptibility to Osteoporotic Fractures. Nutrition and Osteoporosis. New York City: Springer; 1994. pp. 129–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cauley JA, Lui L-Y, Ensrud KE, Zmuda JM, Stone KL, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR. Bone mineral density and the risk of incident nonspinal fractures in black and white women. JAMA. 2005;293:2102–2108. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fleet JC, Harris SS, Wood RJ, Dawson‐Hughes B. The BsmI vitamin D receptor restriction fragment length polymorphism (BB) predicts low bone density in premenopausal black and white women. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:985–990. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]