Abstract

Background. Early initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–infected infants controls HIV-1 replication and reduces mortality.

Methods. Plasma viremia (lower limit of detection, <2 copies/mL), T-cell activation, HIV-1–specific immune responses, and the persistence of cells carrying replication-competent virus were quantified during long-term effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in 4 perinatally HIV-1–infected youth who received treatment early (the ET group) and 4 who received treatment late (the LT group). Decay in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proviral DNA levels was also measured over time in the ET youth.

Results. Plasma viremia was not detected in any ET youth but was detected in all LT youth (median, 8 copies/mL; P = .03). PBMC proviral load was significantly lower in ET youth (median, 7 copies per million PBMCs) than in LT youth (median, 181 copies; P = .03). Replication-competent virus was recovered from all LT youth but only 1 ET youth. Decay in proviral DNA was noted in all 4 ET youth in association with limited T-cell activation and with absent to minimal HIV-1–specific immune responses.

Conclusions. Initiation of early effective cART during infancy significantly limits circulating levels of proviral and replication-competent HIV-1 and promotes continuous decay of viral reservoirs. Continued cART with reduction in HIV-1 reservoirs over time may facilitate HIV-1 eradication strategies.

Keywords: continuous HIV-1 decay, proviral reservoirs, early antiretroviral therapy, prolonged viral suppression, reduced HIV reservoirs

(See the editorial commentary by Li and Gandhi on pages 1519–22.)

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) remains the primary mode of pediatric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Antiretroviral prophylaxis and maternal antiretroviral therapy (ART) have decreased MTCT, but >260 000 new pediatric infections occur globally each year [1]. Perinatally infected children experience more-rapid disease progression than adults [2, 3]. In limited-resource settings, one half of perinatally infected children die by their second birthday, while 75% die by their third birthday [4].

The initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) within the first several months of life effectively controls HIV-1 replication, preserves immune function [5–8], and markedly reduces HIV-1–related mortality [9]. Early diagnosis of HIV-1 infection with prompt initiation of cART in HIV-1–infected infants is thus recommended globally [10, 11]. Available data suggest that early therapy limits replication-competent HIV-1 reservoirs [12] and HIV-1 quasispecies diversity [13]. However, latently infected, resting CD4+ T cells carrying replication-competent HIV-1 remain detectable in most children (80%) studied up to 5 years following early initiation of therapy [13]. As a result, lifelong therapy, which is expensive and potentially toxic, is currently recommended.

Because larger numbers of children access early cART and highly sensitive techniques to characterize and measure HIV-1 reservoirs have evolved, we have begun to use these techniques to characterize HIV-1 reservoirs in children undergoing durable suppression of virus replication following early cART. Here, we report long-term follow-up of a small cohort of perinatally infected youth aged 14–18 years who initiated cART between 2 and 11 weeks of age and who have maintained suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA to below the limits of detection of clinical assays for up to 18 years following cART initiation.

METHODS

Study Cohorts

Perinatally HIV-1–infected youth who initiated cART between 0.5 and 2.6 months of age (the early treatment [ET] group) through clinical trials underwent extensive evaluation to quantify the persistence of HIV-1 proviral and replication-competent reservoirs, along with analysis of low-level plasma viremia and HIV-1–specific immune responses. Four perinatally infected youth who began ART during established infection (ages 6–14.7 years, in keeping with contemporaneous treatment guidelines from the Department of Health and Human Services) and who controlled HIV-1 replication (defined as a plasma HIV-1 RNA load of <50 copies/mL) after receiving cART for 4.5–10.7 years (median duration, 9.6 years; the late-treatment [LT] group) were also studied. HIV-1 infection was diagnosed using standard criteria [10]. The University of Massachusetts Medical School and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine institutional review boards approved this study. Signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their guardians.

HIV-1–Specific Immune Responses and HLA Typing

HIV-1 antibody testing was performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and Western blot testing (Cambridge Biotech HIV-1 Western Blot Kit; Maxim Biomedical, Rockville, MD). Intracellular cytokine assays were used to detect HIV-1–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to pooled peptides [14]. CD4+ T-cell and CD8+ T-cell coexpression of HLA-DR were measured by flow cytometry. HLA typing was performed using the Bio-Rad HLA SSP kit (Sequence Specific Primers; Dreieich, Germany).

Detection and Measurement of Plasma HIV-1 RNA Levels

Standard HIV-1 RNA testing (Roche Monitor Assay: routine lower limit of detection [LOD] of <400 copies/mL and ultrasensitive LOD of <50 copies/mL; Versant HIV-1 RNA 3.0 Assay: branched DNA LOD of <75 copies/mL) was conducted in Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories. Low-level viremia was quantified in plasma, using a modified Roche Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas Taqman HIV-1 test, version 2.0 (LOD, <2 copies/mL), in quadruplicate.

Quantification of Proviral HIV-1 DNA Burden in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), Total Resting CD4+ T Cells, and Memory CD4+ T-Cell Subsets

PBMCs were isolated from whole blood by using a standard Ficoll separation technique. Resting CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by using magnetic beads. To quantify the contribution of memory CD4+ T-cell subsets to the total proviral DNA, cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, washed, and rested overnight. Cells were then stained using an antibody cocktail containing the live-dead discriminator (LDB, Invitrogen) and CD14 (V500, BD Pharmingen), to exclude dead cells and monocytes; CD3 (PacBlue, Invitrogen) and CD4 (Alexa 700, BD Pharmingen), to sort for total CD4 T cells; CD69, HLA-DR, and CD25, (FITC, BD Pharmingen and Beckman Coulter), to discriminate and sort for resting CD4+ T cells; and CD45RA (ECD, Beckman Coulter), CCR7 (PeCy7, BD Pharmingen), and CD27 (APC, BD Pharmingen), to sort for the following CD4+ T-cell subpopulations: central memory cells (CD45RA−CCR7+CD27+), transitional memory cells (CD45RA−CCR7−CD27+), effector memory cells (CD45RA−CCR7−CD27−), and naive cells (CD45RA+CCR7+CD27+). The purities of each sorted memory CD4+ T-cell population exceeded 95%. Sorted cell populations were pelleted, cryopreserved, and stored as dry cell pellets until analysis. Levels of proviral DNA and 2-long terminal repeat circles in PBMCs, resting CD4+ T cells, and CD4+ T-cell subsets were measured using a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction assay (detection limits, <3–4 copies/106 cells [15]).

Evaluation of Decay of HIV-1 Proviral DNA Over Time

Models were fit using linear regression on log10 HIV-1 DNA copy numbers. For the combined model, these values were scaled, dividing by the patient's maximum count, before calculating the logarithm. Statistical significance of the exponential decay models was evaluated by way of the root mean square error (RMSE), calculated as the square root of the average square error of the model prediction over the available time points. The null hypothesis that the RMSE occurred by chance was evaluated using a permutation test (10 000 permutations of the time order).

Quantification of Replication-Competent HIV-1

Replication-competent HIV-1 was measured in resting CD4+ T cells, using an enhanced quantitative virus outgrowth assay [12]. Cell inputs ranged from 10 million to 24 million cells.

RESULTS

Study Subjects

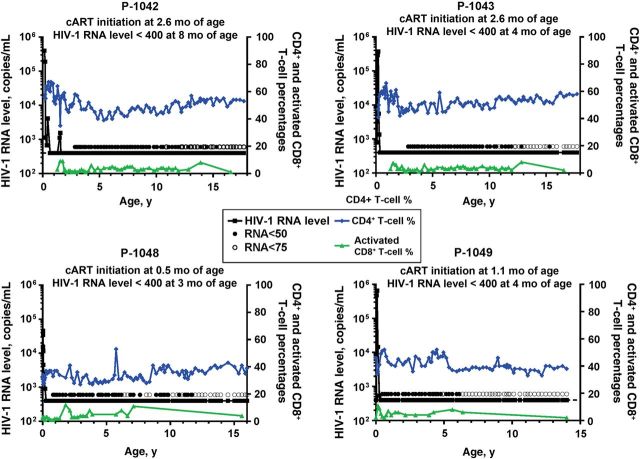

Four ET youth and 4 LT youth were studied (Table 1). All ET youth began cART prior to 2.6 months of age and have been followed through 14–17.7 years of age (Figure 1). These 4 youth cleared plasma HIV-1 RNA to undetectable levels, as measured by routine clinical assays, within a median of 13 weeks of starting cART; the age at suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA to <400 copies/mL ranged from 3 to 8 months. Three have maintained consistently undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA levels during cART. The fourth youth (P-1042) had 2 isolated plasma HIV-1 RNA values of 1100 and 1600 copies/mL at 18 months of age despite reported adherence to the cART regimen. After changing the cART regimen, plasma HIV-1 RNA became undetectable by 19 months of age and has remained undetectable through 17.7 years of age. In all 4 ET youth, CD4+ T-cell counts have remained within normal limits for age. None of the ET youth had HLA class I alleles (ie, HLA B*13, B*57, B*58, or B*81) associated with spontaneous control of HIV-1 replication (Table 1) [16].

Table 1.

Study Cohort Characteristics

| Cohort, Patient | Age at Study, y | Current cART Regimen | cART Duration, y | CD4+ T-Cell Percentage | CD4+ T-Cell Count | CD4+ T-Cell:CD8+ T-Cell ratio | HLA Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early treated | |||||||

| P-1042 | 17.7 | 2 NRTIs + 1 PI/boosted | 17.5 | 53 | 935 | 2.8 | A26, A30, B18, B39, Cw5, Cw12 |

| P-1043 | 17.7 | 2 NRTIs + 1 PI/boosted | 17.5 | 58 | 951 | 2.8 | A11, A26, B39, B51, Cw3, Cw12 |

| P-1048 | 16 | 2 NRTIs + 1 NNRTI | 15.8 | 39 | 1328 | 1.4 | A29, A30, B44, Cw4, Cw16 |

| P-1049 | 14 | 2 NRTIs + 1 PI | 13.9 | 38 | 689 | 1.4 | A1, A2, B7, B50, Cw6, Cw7 |

| Overall, median (IQR) | 16.9 (14.5–17.7) | … | 16.7 (14.4–17.5) | 46 (38–57) | 943 (751–1234) | 2.1 (1.4–2.8) | … |

| Late treated | |||||||

| P-1376 | 22 | 3 NRTIs + 1 PI/boosted | 9.4 | 32 | 452 | 0.6 | A1, A2, B7, B35, Cw4 |

| P-1377 | 23 | 2 NRTIs + 1 PI/boosted | 9.8 | 23 | 500 | 0.5 | A30, A68, B7, B35, Cw7 |

| P-1378 | 19 | 1 NRTI + 1 NNRTI + 1 PI | 4.5 | 30 | 1008 | 0.8 | A23, A30, B7, B15, Cw3, Cw7 |

| P-1379 | 23 | 1 NRTI + 1 NNRTI + 1 PI/boosted | 10.7 | 18 | 397 | 0.3 | A2, A68, B15,B48, Cw1, Cw8 |

| Overall, median (IQR) | 22.5 (19.8–23) | … | 9.6 (5.7–10.5) | 27 (19–32) | 476 (411–881) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | … |

Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Circulating human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA levels, CD4+ T-cell percentages, and activated CD8+ T-cell percentages over time in youth who received early treatment. Abbreviation: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy.

Undetectable Plasma Viremia and Limited HIV-1–Specific T-Cell Responses in ET Youth During cART Suggest Restricted Viral Production

By use of highly sensitive assays, low levels of HIV-1 RNA can be detected in nearly 60%–70% of HIV-1–infected individuals receiving cART who have plasma HIV-1 RNA levels below the detection limit of routine clinical assays [17]. The origins of this viremia are incompletely understood but likely represent either HIV-1 expression from established proviral reservoirs and/or low levels of ongoing HIV-1 replication. Ultrasensitive assays were used to evaluate the extent of virus production during long-term cART that was initiated early. These assays revealed that the HIV-1 RNA levels in plasma specimens from all 4 ET youth were below the limits of detection (<2 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL; Table 2). By contrast, HIV-1 RNA (median level, 8 copies/mL; range, 4–14 copies/mL) was readily detectable by ultrasensitive assays in plasma specimens from all 4 LT youth (P = .03).

Table 2.

Quantitation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA and DNA in Peripheral Blood

| Cohort, Patient | Age at Study, y | Proviral DNA Load, Copies/106 PBMCs | Proviral DNA Load, Copies/106 Resting CD4+ T Cells | 2-LTR DNA Circles, Copies/106 PBMCs | 2-LTR DNA Circles, Copies/106 Resting CD4+ T Cells | Replication-Competent Virus |

Residual Viremia, RNA Copies/mL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IU/106 Cells | Resting CD4+ T Cells Cultured, No., ×106 | |||||||

| Early treated | ||||||||

| P-1042 | ||||||||

| V1 | 16.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | <0.1 | 10 | ND |

| V2 | 16.6 | 8.9 | ND | <4 | ND | <0.1 | 14.5 | <2 |

| V3 | 17.7 | 12.0 | 9.7 | <4 | <4 | <0.11 | 15 | <2 |

| P-1043 | ||||||||

| V1 | 16.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | <0.1 | 12.5 | ND |

| V2 | 16.6 | <4 | ND | <4 | ND | <0.1 | 17 | <2 |

| V3 | 17.7 | 6.6 | <4 | <4 | <4 | <0.1 | 24 | <2 |

| P-1048 | ||||||||

| V1 | 14.5 | <4 | ND | <4 | ND | <0.1 | 21 | <2 |

| V2 | 15.9 | <4 | <4 | <4 | <4 | 0.05 | 19.5 | <2 |

| P-1049 | ||||||||

| V1 | 13.1 | 5.5 | ND | <4 | ND | <0.1 | 12 | <2 |

| V2 | 14.0 | 8.3 | 8.2 | <4 | <4 | ND | ND | ND |

| Late treated | ||||||||

| P-1376 | ||||||||

| V1 | 22.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.51 | 12.5 | ND |

| V2 | 22.0 | 190.7 | ND | 6.8 | ND | 1.05 | 12.5 | 3.5 |

| P-1377 | ||||||||

| V1 | 23.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.83 | 12.5 | ND |

| V2 | 23.0 | 172.0 | ND | 11.0 | ND | 1.61 | 12.5 | 10.5 |

| P-1378 | ||||||||

| V1 | 19.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3.25 | 12.5 | ND |

| V2 | 19.0 | 345.0 | ND | 0.0 | ND | 1.11 | 12.5 | 13.8 |

| P-1379 | ||||||||

| V1 | 23.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.51 | 12.5 | ND |

| V2 | 23.0 | 68.0 | ND | 5.0 | ND | 0.22 | 12.5 | 4.5 |

Abbreviations: IU, infectious units; LTR, long terminal repeat; ND, not done; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

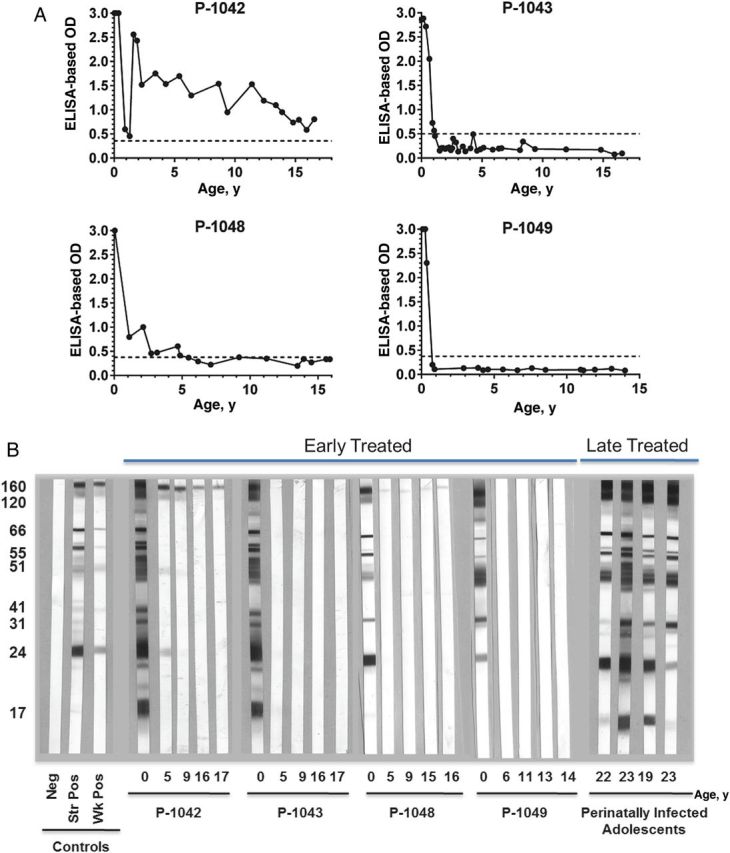

Immune correlates of HIV-1 replication were also evaluated. Activated CD8+ T-cell subsets coexpressing HLA-DR expand with ongoing viral replication [18]. The frequencies of activated CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood of the ET youth (Figure 1) did not exceed those in HIV-1–uninfected children [19]. HIV-1–specific antibodies were undetectable by ELISA in 3 of the 4 ET youth (Figure 2A) and by Western blot in 2 youth (P-1043 and P-1049; Figure 2B). Single reactive bands to gp160 were detected by Western blot in the peripheral blood of 2 ET youth (P-1042 and P-1048; Figure 2B). By contrast, all 4 LT youth maintained strong responses to all 9 HIV-1 proteins tested on Western blot.

Figure 2.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antibodies levels over time in youth with long-term suppression of HIV-1 replication who initiated combination antiretroviral therapy early or late. A, Antibody levels in early treated youth, determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). B, Western blot findings for in early treated and late-treated youth. Abbreviations: Neg, negative results; str pos, strongly positive results; wk pos, weekly positive results.

Similarly, HIV-1–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses were not detected in any of the ET youth, despite normal CD4+ T-cell responses to staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) and normal CD8+ T-cell responses to SEB and phytohemagglutinin (data not shown). By contrast, HIV-1–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected in all 4 LT youth. Prior to cART initiation at 2.6 months of age, HIV-1 gag-, nef-, and tat-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in P-1042 and HIV-1 rev–specific CD8+ T cells were detected in P-1043; HIV-1–specific CD8+ T-cell responses have not been detected upon subsequent retesting. Together, these data suggest extremely limited or no ongoing HIV-1 production in the ET youth during prolonged cART.

Limited HIV-1 Persistence in ET Youth With Prolonged HIV-1 Suppression Following Early Initiation of cART

The persistence of HIV-1 reservoirs carrying viral DNA represent a barrier to cure. Extraordinarily low levels of HIV-1 proviral DNA were detected in PBMCs from ET youth (median, 7 copies/million PBMCs; range, 4–12 copies/million PBMCs; Table 2). These levels were substantially lower than those detected in the LT youth (median, 181 copies/million PBMCs; range, 68–345 copies/million PBMCs; P = .03). Given the evidence for little or no ongoing viral replication in the ET youth, it is likely that the detectable DNA primarily represents integrated provirus. HIV-1 DNA copy numbers in ET youth, which were just above the detection limits of the assay (ie, 3–4 copies per million PBMCs), remained at extremely low levels even after enrichment of the PBMCs for CD4+ T cells, a known HIV-1 reservoir. Similar studies could not be performed for the LT youth because of a lack of available samples.

Not all integrated proviruses are replication competent. We determined the frequency of cells carrying replication-competent viruses that could be recovered from between 10 million and 24 million resting CD4+ T cells (Table 2). The frequencies of latently infected resting CD4+ T cells were below the limit of detection (<0.1 infectious units/million cells) in all ET youth, whereas replication-competent viruses were recovered from all LT youth at 0.22–3.25 infectious units/million cells. Of the 9 viral outgrowth assays performed for ET youth, only 1 of 20 replicates (1 million cells each) tested positive for replication-competent virus from subject P-1048 at the second time point, which is roughly equivalent to approximately 0.05 infectious units/million cells (Table 2). HIV-1 envelope V1–V5 sequences of isolates from this culture-positive well revealed very little sequence evolution when compared to viruses directly sequenced from plasma obtained prior to therapy, at 2 weeks of age (data not shown).

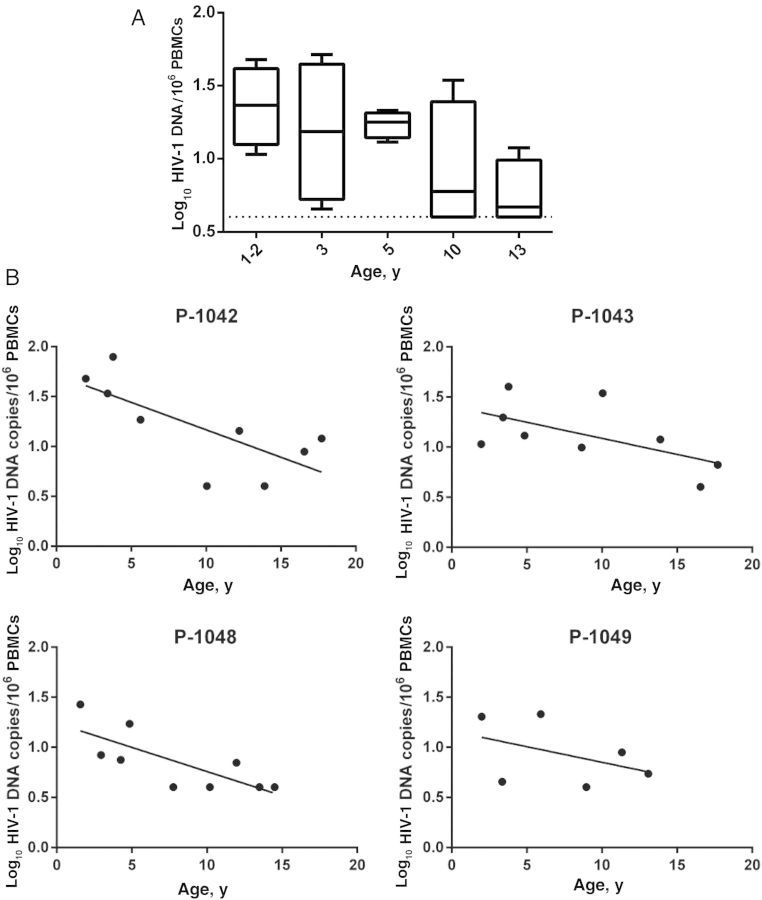

HIV-1 Proviral Reservoirs Decay Over Time During cART Receipt

The PBMC HIV-1 DNA levels measured in ET youth were lower than those described in most HIV-1–infected adults [20] or children receiving cART [21]. Previous longitudinal studies conducted within several years of cART initiation in adults or children suggested an initial steep decline in proviral reservoir size, followed by a slower decline [22–25]. Extrapolation of data from those earlier studies suggested that even with potent cART, eradication of the proviral reservoir would not be achievable within the lifetime of the individual. To examine the stability of HIV-1 DNA levels over time in ET individuals receiving cART, we measured HIV-1 DNA levels in cryopreserved PBMCs obtained at 1–2, 3, 5, 10, and 13 years of age (Figure 3). At the earliest time points tested (1–2 years), HIV-1 proviral DNA copy numbers ranged between 1 and 1.5 log10 copies per million PBMCs; proviral DNA copy numbers remained within this range for tests performed through 5 years of age. By 10 and 13 years of age, HIV-1 proviral copy numbers fell to a median of 0.6–0.7 log10 copies per million PBMCs (Figure 3). Each patient's HIV-1 DNA was fit to an exponential decay model. An overall trend in decay of proviral DNA copy number over time was observed and was statistically significant for the 3 patients with sufficient data (P-1042: P = .02; P-1043: P = .03; P-1048: P = .01; ad P-1049, with only 6 data points: P = .17). Variability in the counts appeared to decrease over time, but additional data from more subjects are needed to confirm that trend. To increase the power of the analysis, the 4 patients' normalized HIV-1 DNA data were collectively fit to an exponential decay model (data not shown). Again, the model reflected the general trend (P < 10−4). The patients' CD4+ T-cell percentages and absolute counts remained stable over the period of analysis (Figure 1), and virtually identical results were observed when proviral decay rates were analyzed using the proviral copy number, expressed per million CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3.

Decay in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) proviral DNA level over time in youth with long-term suppression of HIV-1 replication who initiated combination antiretroviral therapy early. A, Variability in HIV-1 proviral DNA levels over time. Data are medians with interquartile ranges. B, HIV-1 proviral DNA decay curves among individual patients. Abbreviation: PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

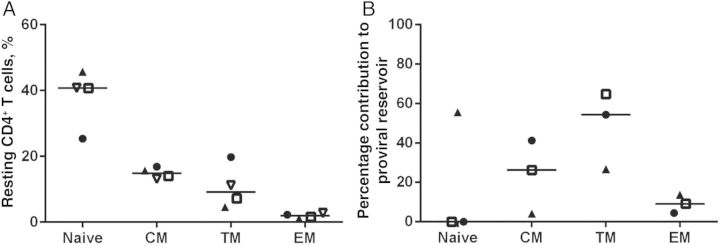

Contribution of Memory CD4+ T-Cell Subsets to the Total Circulating HIV-1 Proviral Reservoir

The observed decay in HIV-1 proviral DNA levels over time was slower than that reported for adults studied within 1–2 years following cART initiation [25]. The variable decay rates over time following cART initiation suggests variability in cellular reservoirs that harbor proviral DNA. The observed proviral decay in the absence of detectable HIV-specific immune responses also suggests that early therapy might limit seeding of long-lived cellular reservoirs. We therefore examined the distribution of proviral DNA in resting memory CD4+ T-cell subsets from 3 ET youth with prolonged HIV-1 suppression following early cART. In this very small sample, transitional memory CD4+ T cells made a larger contribution to the pool of resting CD4+ T cells harboring HIV-1 proviruses than central memory or effector memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 4). This pattern differs from that reported in individuals who initiated therapy after chronic infection, in whom central memory CD4+ T cells contribute most heavily to the proviral reservoir [26], but is similar to that described in a cohort of so-called posttreatment controllers who initiated cART during primary infection and successfully controlled HIV-1 replication after therapy cessation [27].

Figure 4.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) proviral DNA levels in memory CD4+ T cells from youth with long-term suppression of HIV-1 replication who initiated combination antiretroviral therapy early. A, Normal CD4+ memory T-cell subsets for age in early treated youth. B, Proportional contribution of memory CD4+ T-cell subsets to the proviral reservoir in early treated youth. Abbreviations: CM, central memory; EM, effector memory; TM, transitional memory.

DISCUSSION

We characterized HIV-1 persistence in 4 ET youth in whom plasma HIV-1 RNA was consistently undetectable by routine clinical assays for 13–17.5 years to determine whether prolonged suppression of HIV-1 replication following early cART alters HIV-1 persistence. The paucity of detectable residual viremia, circulating activated T cells, and HIV-1–specific immune responses suggests restriction of ongoing HIV-1 production. Very low frequencies of PBMCs bearing HIV-1 DNA were detected, and we were unable to isolate replication-competent virus from resting CD4+ T cells (10–24 million) of most ET youth. Of importance is the novel finding that proviral HIV-1 copy numbers in circulating PBMCs decreased over a decade or more of virologic suppression during cART.

The levels of HIV-1 proviral DNA in the ET youth were low and are similar to those described in adult long-term follow-up studies of effective early cART and in elite controllers [24, 28]. In fact, most of the study participants had levels in whole PBMCs that were just above the detection limits (3–4 copies per million PBMC) of a highly sensitive assay. Proviral HIV-1 reservoirs are rapidly established in primary infection and serve as a barrier to cure; Ananworanich et al [29] demonstrated a gradual increase in gut and peripheral blood proviral reservoirs over the course of primary infection. Strain et al [25] reported marked reduction in proviral DNA levels in PBMCs from adults over the first 2 years of cART that was initiated during primary infection. Chun et al [30] and Hocqueloux et al [31] reported significantly lower circulating HIV-1 DNA copy numbers in adults who initiated treatment early, compared with those who initiated treatment late. Together, these data suggest that the initiation of cART early in primary infection markedly restricts the size of the proviral HIV-1 DNA reservoir. HIV-1 proviral DNA copy numbers in our cohort, at 1–2 years of age (the earliest time point that limited cryopreserved PBMC repository permitted us to evaluate), ranged between 1 and 1.5 log10 copies per million PBMCs, which is equivalent to or lower than values reported 1 year after initiating cART during primary infection in adults [25].

The proviral DNA levels in ET youth at 1–2 years of age were also much lower than pretherapy PBMC-specific DNA levels of 2.85 log10 DNA per million PBMCs in 14 children who initiated cART at a median of 9 years of age [21]. The latter levels are similar to those observed in the LT youth, who initiated cART at a median age of 13 years and in whom evidence of ongoing viremia suggests likely ongoing replenishment of the proviral DNA reservoir. Lack of longitudinal PBMC samples precluded examination of the decay in circulating HIV-1 proviral DNA levels in LT youth. In the cohort described by Zanchetta et al [21], HIV-1 proviral copy numbers fell by a mean of about 1 log after 4 years of therapy; HIV-1 DNA decay rates were slower in children with detectable levels of unspliced HIV-1 RNA, again suggesting that residual HIV-1 replication may contribute to the stability of the HIV-1 proviral reservoir.

Hocqueloux et al [31] reported that individuals treated during primary infection have similar pretherapy levels of HIV-1 proviral DNA copy numbers as individuals treated during chronic infection. However, they noted more-rapid decay of HIV-1 DNA in early treated than late-treated adults; moreover, 90% of individuals treated during primary infection but only 20% of individuals treated during chronic infection had <2.3 log10 DNA copies/million PBMCs after 6 years of HIV-1 RNA suppression. Altogether, the data suggest that early suppressive cART reduces the number of long-lived cells harboring HIV-1 proviral DNA; restriction of ongoing HIV-1 replication may limit reservoir replenishment over time.

In the ET youth, the decay of proviral DNA in the absence of detectable HIV-specific immunity suggests that early cART may restrict seeding of long-lived reservoirs. Buzon et al [32] have recently reported a significant decrease in proviral DNA levels in effector memory and terminally differentiated CD4+ T cells over a median of 8 years in a group of adults who initiated cART during primary infection. Long-lived central memory CD4+ T cells appear to harbor the majority of proviral DNA in chronically infected individuals. Of interest, measurement of HIV-1 proviral DNA in memory CD4+ T-cell subsets in 3 ET youth demonstrated that transitional memory CD4+ T cells make a larger contribution to CD4+ T-cell proviral levels than central memory CD4+ T cells. Longer-lived central memory CD4+ T cells also made a smaller contribution to overall proviral DNA levels in a cohort of early treated adults in whom decay of HIV-1 replication was observed during cART [27]. Together, these data, along with the case of remission in a baby who initiated cART within 31 hours of birth [33], suggest that early or very early initiation of cART may limit the infection of long-lived cells that serve as the barrier to HIV-1 cure. Additional pediatric studies are planned to test this hypothesis.

An important question that arises is whether the ET youth have sufficiently limited replication-competent HIV-1 reservoirs to preclude a rebound in plasma viremia after cART cessation. HIV-1 proviral DNA levels measured in the ET youth are well below levels reported (median, 1.71 log copies/million PBMCs) in a group of postreatment controllers, with long-term (>10 years) suppression of HIV-1 replication following cART cessation after having received treatment during primary infection [27]. Several groups [12, 34, 35] have shown that early initiation of cART restricts but does not eliminate latent infection of resting CD4+ T cells [35]. The fact that we recovered little or no replication-competent virus from ET youth is unusual and suggests that detectable HIV-1 proviruses may have compromised replicative potential [20].

One caveat is that blood volume restrictions limited the maximum available number of cells for our replication-competent virus assays. Very low levels of proviral DNA may hamper the recovery of replication-competent HIV-1 from relatively small cell volumes [20]. Indeed, repeated testing of 1 ET individual (P-1048) yielded replication-competent virus despite extremely low to undetectable levels of HIV-1 proviral DNA. Eriksson et al [20] recovered replication-competent HIV-1 from 2 individuals with proviral DNA levels below the detection limits of their assays (2 copies/million PBMCs), suggesting the stochastic nature of virus recovery when circulating levels of HIV-1 provirus are low. Together, these data emphasize the desirability of obtaining larger numbers of PBMCs or CD4+ T cells (available from blood volumes of >500 mL or by leukapheresis) to allow more-definitive measurement of the total and replication-competent HIV-1 proviral reservoirs.

The decay in PBMC HIV-1 proviral DNA, along with little or no recoverable replication-competent HIV-1, suggest that lifelong therapy may not be necessary for all individuals, particularly those who initiate cART during primary infection. However, further work is necessary to define parameters of viral reservoirs predictive of successful control of HIV-1 replication after cART cessation. In this regard, it is important to point out that Chun et al [30] observed rebound of plasma viremia following cessation of ART in an individual despite profoundly low levels of replication-competent HIV-1 reservoirs. Moreover, the recent report of HIV-1 rebound in 2 individuals without detectable circulating provirus or replication-competent virus following stem cell transplantation in combination with cART [36] also highlights the need to define improved markers for the presence of replication-competent virus in individuals participating in HIV-1 cure protocols. Until we understand this more fully, it is prudent for all HIV-1–infected patients to continue receiving suppressive ART.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the children, for participating in these studies; their families, for support; Linda Lambrecht, Joyce Pepe, Robin Brody, and Steven Lada, for technical support; and Mindy Donovan, for manuscript preparation.

K. L. and D. P. designed the studies; Y. H. C., C. Z., D. R., M. S., T. W. C., and D. M. conducted the experiments; K. L., D. P., C. Z., C. K. C., M. M., D. R., M. S., M. G., and B. T. analyzed the data; and all authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R21 AI100656 to D. P. and UM1 AI069516 to K. L.); the Collaboratory of AIDS Researchers for Eradication (grants P01 AI080193, UM1 AI69432, R01 AI047745, P01 AI74621, and U19 AI096113 to D. R.); the American Foundation for AIDS Research (to D. P. and K. L.); the Department of Veterans Affairs (to D. R.); the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust (to D. R.); the University of Massachusetts Center for AIDS Research (grant P30 AI042845 to K. L.); the University of California, San Diego, Center for AIDS Research (grant P30 AI036214 to D. R.); the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research (grant P30 AI094189 to D. P.); and the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (grant P30 AI064518 to C. K. C.), through funding from the National Institutes of Health .

Potential conflicts of interest. K. L. has served as a consultant to Tibotec and Up To Date; DP has served as a consultant to Viiv Healthcare; and D. R. has served as a consultant to Biota, Chimerix, BMS, Gilead, Gen-Probe, Monogram, Sirenas, and Prism. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf. Accessed 7 November 2013.

- 2.Shearer WT, Quinn TC, LaRussa P, et al. Viral load and disease progression in infants infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1337–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705083361901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson BA, Mbori-Ngacha D, Lavreys L, et al. Comparison of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral loads in Kenyan women, men, and infants during primary and early infection. J Virol. 2003;77:7120–3. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7120-7123.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newell ML, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, Rollins N, Gaillard P, Dabis F. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1236–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luzuriaga K, Bryson Y, Krogstad P, et al. Combination treatment with zidovudine, didanosine, and nevirapine in infants with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1343–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705083361902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luzuriaga K, McManus M, Catalina M, et al. Early therapy of vertical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection: control of viral replication and absence of persistent HIV-1-specific immune responses. J Virol. 2000;74:6984–91. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6984-6991.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luzuriaga K, McManus M, Mofenson L, Britto P, Graham B, Sullivan JL. A trial of three antiretroviral regimens in HIV-1-infected children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2471–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadwick EG, Rodman JH, Britto P, et al. Ritonavir-based highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected infants younger than 24 months of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:793–800. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000177281.93658.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/2/pediatric-treatment-guidelines/0. Accessed 7 November 2013.

- 11.Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection—recommendations for a public health approach. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf. Accessed 7 November 2013.

- 12.Persaud D, Palumbo PE, Ziemniak C, et al. Dynamics of the resting CD4(+) T-cell latent HIV reservoir in infants initiating HAART less than 6 months of age. AIDS. 2012;26:1483–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283553638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Persaud D, Ray SC, Kajdas J, et al. Slow human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution in viral reservoirs in infants treated with effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:381–90. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenough TC, Cunningham CK, Muresan P, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of recombinant poxvirus HIV-1 vaccines in young adults on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Vaccine. 2008;26:6883–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strain MC, Lada SM, Luong T, et al. Highly precise measurement of HIV DNA by droplet digital PCR. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emu B, Sinclair E, Hatano H, et al. HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses may contribute to the control of human immunodeficiency virus infection, but such responses are not always necessary for long-term virus control. J Virol. 2008;82:5398–407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer S, Maldarelli F, Wiegand A, et al. Low-level viremia persists for at least 7 years in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giorgi JV, Detels R. T-cell subset alterations in HIV-infected homosexual men: NIAID Multicenter AIDS cohort study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;52:10–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shearer WT, Rosenblatt HM, Gelman RS, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:973–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson S, Graf EH, Dahl V, et al. Comparative analysis of measures of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 eradication studies. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanchetta M, Walker S, Burighel N, et al. Long-term decay of the HIV-1 reservoir in HIV-1-infected children treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1718–27. doi: 10.1086/504264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luzuriaga K, Wu H, McManus M, et al. Dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vertically infected infants. J Virol. 1999;73:362–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.362-367.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med. 1999;5:512–7. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blankson JN, Finzi D, Pierson TC, et al. Biphasic decay of latently infected CD4+ T cells in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1636–42. doi: 10.1086/317615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strain MC, Little SJ, Daar ES, et al. Effect of treatment, during primary infection, on establishment and clearance of cellular reservoirs of HIV-1. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1410–8. doi: 10.1086/428777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. 2009;15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Julg B, Pereyra F, Buzon MJ, et al. Infrequent recovery of HIV from but robust exogenous infection of activated CD4(+) T cells in HIV elite controllers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:233–8. doi: 10.1086/653677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ananworanich J, Schuetz A, Vandergeeten C, et al. Impact of multi-targeted antiretroviral treatment on gut T cell depletion and HIV reservoir seeding during acute HIV infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chun TW, Justement JS, Murray D, et al. Rebound of plasma viremia following cessation of antiretroviral therapy despite profoundly low levels of HIV reservoir: implications for eradication. AIDS. 2010;24:2803–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340a239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Jacquot S, et al. Long-term antiretroviral therapy initiated during primary HIV-1 infection is key to achieving both low HIV reservoirs and normal T cell counts. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1169–78. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buzon MJ, Sun H, Li C, et al. HIV-1 persistence in CD4(+) T cells with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2014;20:139–42. doi: 10.1038/nm.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, et al. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1828–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Archin NM, Vaidya NK, Kuruc JD, et al. Immediate antiviral therapy appears to restrict resting CD4+ cell HIV-1 infection without accelerating the decay of latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9523–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120248109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chun TW, Murray D, Justement JS, et al. Relationship between residual plasma viremia and the size of HIV proviral DNA reservoirs in infected individuals receiving effective antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:135–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henrich T. Challenges and strategies towards functional cure: how low do you need to go [abstract 45]. Sixth International Workshop on HIV Persistence,; Miami, Florida. 2013. [Google Scholar]