Abstract

Active ingredients of spices (AIS) modulate neural response in the peripheral nervous system, mainly through interaction with TRP channel/receptors. The present study explores how different AIS modulate neural response in layer 5 pyramidal neurons of S1 neocortex. The AIS tested are agonists of TRPV1/3, TRPM8 or TRPA1. Our results demonstrate that capsaicin, eugenol, menthol, icilin and cinnamaldehyde, but not AITC dampen the generation of APs in a voltage- and time-dependent manner. This effect was further tested for the TRPM8 ligands in the presence of a TRPM8 blocker (BCTC) and on TRPM8 KO mice. The observable effect was still present. Finally, the influence of the selected AIS was tested on in vitro gabazine-induced seizures. Results coincide with the above observations: except for cinnamaldehyde, the same AIS were able to reduce the number, duration of the AP bursts and increase the concentration of gabazine needed to elicit them. In conclusion, our data suggests that some of these AIS can modulate glutamatergic neurons in the brain through a TRP-independent pathway, regardless of whether the neurons are stimulated intracellularly or by hyperactive microcircuitry.

Spices are dried seeds, fruit, roots, bark, or other vegetable substances that are added to food in small quantities to provide flavor or color, or as preservatives that kill or prevent the growth of harmful bacteria1. Examples relevant to this study include chilli, cloves, menthol, mustard, wasabi, radish and cinnamon. In many cultures, these and other spices also play an important role in traditional medicine2, where they are used as analgesics and local anaesthetics, as well as to emulate thermosensation3,4.

Some Active Ingredients of Spices (AIS) bind to Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) ion channels - a family of mainly non-selective sodium/calcium channels with greater diversity in activation mechanisms and selectivity than any other family of ion channels. TRP channels have been shown to be involved with signal transduction in vision, taste, olfaction, hearing, touch, and thermo- and osmo-sensation5,6,7,8. A subset of TRP channels is reported to respond to molecules present in spices. For example, TRPV1 is activated by heat (≥43°C) but also responds to capsaicin4, the active compound of chili pepper; eugenol9; anandamide10 (an endocannabinoid); camphor11, a topical analgesic; and piperine, the pungent ingredient in black pepper12. All these compounds produce a psychophysiological sensation of heat or burning. TRPM8 is activated by moderately cool temperatures (<23–28°C)13,14 and by compounds such as menthol15, eucalyptol16, and icilin17, which produce a cooling sensation. TRPA1, which is sometimes co-expressed with TRPV118,19, responds to a vast range of agonists present in spices including allicin and diallyl disulfide (garlic), cinnamaldehyde (cinnamon), gingerol (ginger), α-SOH (Sichuan peppers) and canabinoids20.

Most studies of spices and their interaction with TRP channels have focused on sensory neurons and on the sensory terminals of target organs7. However, it has also been observed that the AIS can cross the blood brain barrier, modulating the activity of the central nervous system (CNS). In particular, capsaicin21, linalool22, and menthol23 are reported to inhibit seizure behaviour in in vivo models of epilepsy.

Here, we have built on this work, systematically investigating the effect of AIS on the electrical behaviour of single neurons and neuronal networks. We find that four active ingredients of spices (capsaicin, eugenol, menthol, cinnamaldehyde) and one synthetic analog (icilin) exert a voltage and time-dependent inhibitory effect on single cell activity, and almost all of the same molecules inhibit bursting activity in cortical preparations. We show that these effects, unlike the effects of spices on sensory neurons, are independent of TRP channels. Spices and their homologues are successful in inhibiting neuronal firing and preventing the release of glutamate in a voltage and time-dependent manner. Our data suggests that spices and their homologues could play a useful role in the treatment of excitotoxicity and associated clinical conditions such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and brain and spinal cord injuries, to mention a few24. We observe that spices, as common foods, have a favorable safety profile, and we propose further work to explore their translational potential.

Results

Dampening of firing activity in single neurons

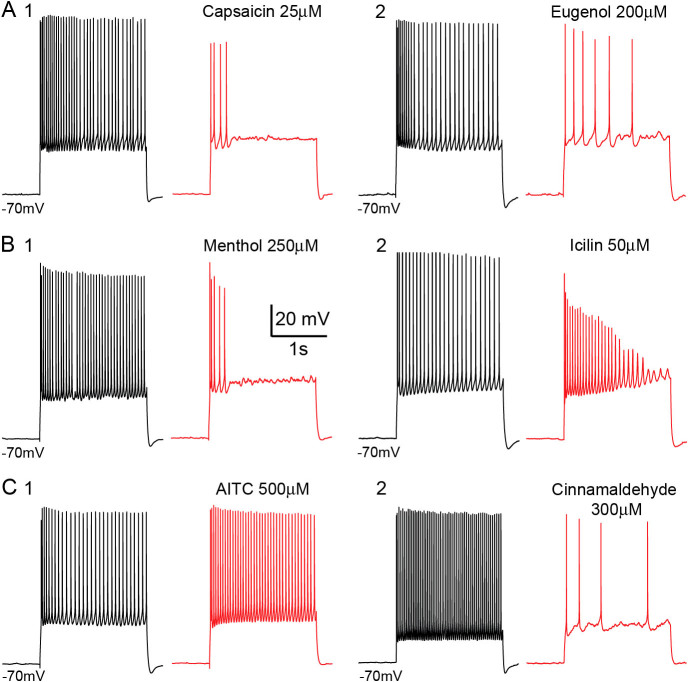

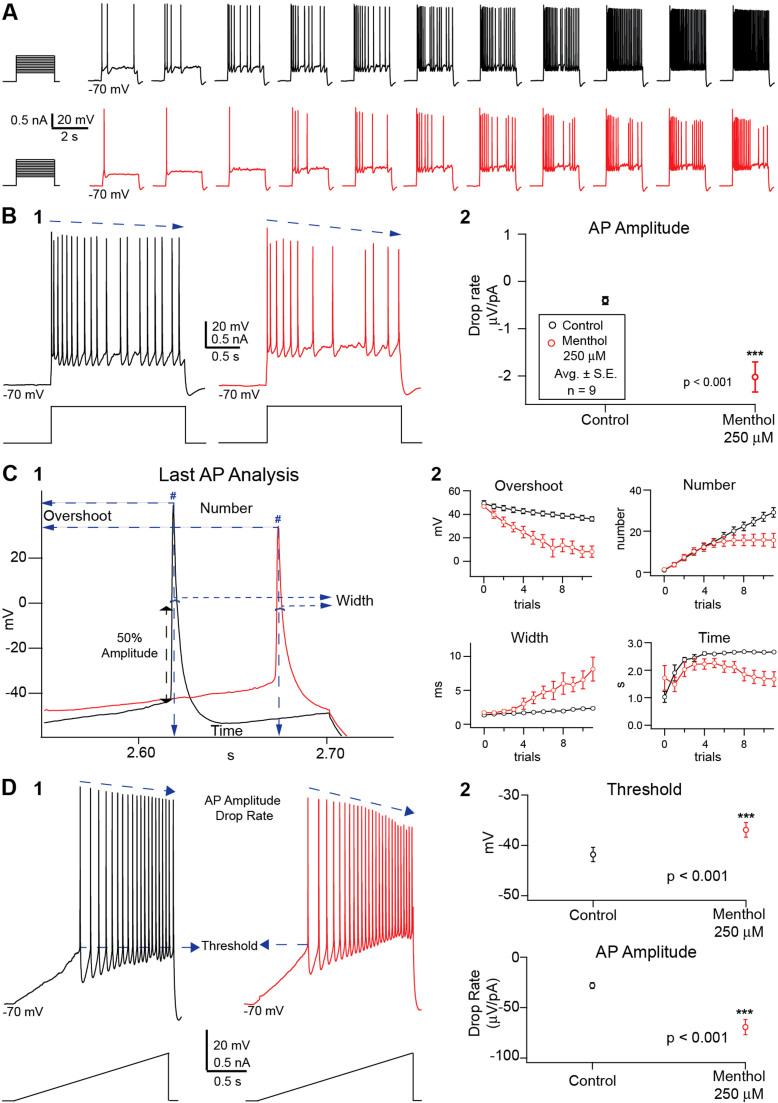

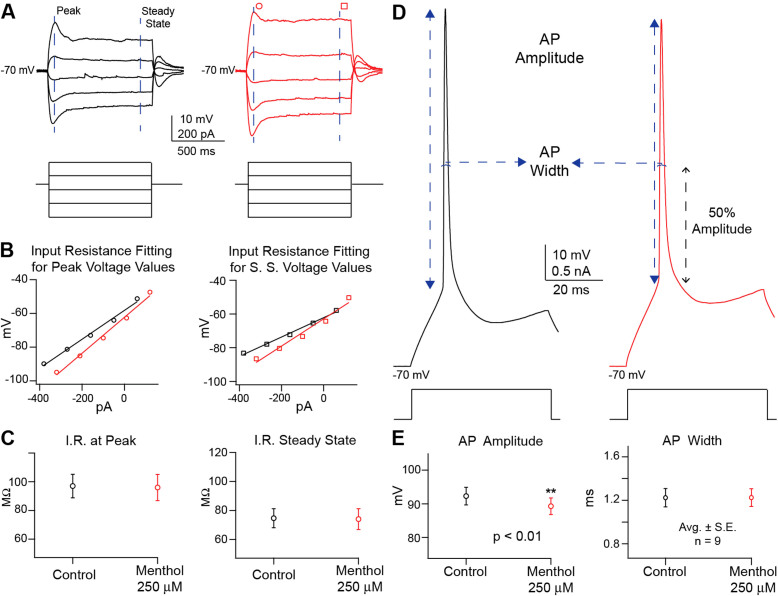

We found that five out of the six AIS (capsaicin, eugenol, menthol, icilin, cinnamaldehyde) induced large, qualitatively similar, voltage and time-dependent changes in the electrical activity of single neurons (Fig 1). These AIS all induced drastic changes in the number and amplitude of APs generated at a given voltage. The effect was observable in all neurons that received the treatment. As an example of the detailed effects, we can examine changes in the electrophysiological behaviour of recorded cells after perfusion with menthol 250 μM (n = 9) (Fig 2). Upon stimulation with a set of consecutively increasing square current pulses, the mean drop in the amplitude of APs between the start and the end of each pulse was significantly larger after perfusion (Fig 2A, 2B). The total number of APs generated after a given number of trials was also significantly lower after perfusion, with the largest gap in later trials when the membrane voltage was highest. The last AP recorded for each pulse was also broader and the time between the beginning of the pulse and the last AP was shorter (Fig 2C). Stimulation with steadily increasing current, leading to increased depolarization (Fig 2D), showed that firing thresholds were significantly higher than in the control condition and late AP amplitudes were lower (Fig 2D2). The drop in amplitude of APs was largest when the cell was highly depolarized. This implies that the effect of menthol is voltage-dependent. With this type of stimulation ligands of TRPV1/3 had a stronger effect, leading in some cases to a total abolition in the generation of APs (data not shown). No significant changes were observed in the input resistance (Fig 3A–C) or in the waveforms of the initial APs at rheobase (Fig 3D–E).

Figure 1. Voltage recordings of single layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the primary somatosensory cortex.

Compared voltage traces of different single cell recordings at high depolarization, in control situation (black) and in the presence of a particular AIS (red). Traces are grouped depending of the corresponding AIS receptors affinity: - TRPV1/3 ligands: 1. - Capsaicin 25 μM; 2. - Eugenol 200 μM. - TRPM8 ligands: 1. - Menthol 250 μM; 2. - Icilin 50 μM. - TRPA1 ligands: 1. - AITC 500 μM; 2. - Cinnamaldehyde 300 μM. Except for AITC all AIS tested tend to affect the generation the APs at high depolarization levels.

Figure 2. Recorded traces of stimuli eliciting AP affected by extracellular menthol 250 μM and corresponding analysis.

Single cell voltage recordings in control conditions (black) and in the presence of menthol 250 μM (red) from S1 somatosensory cortex layer 5 pyramidal neurons. The features extracted were affected by the presence of the AIS. Voltage recordings (A) under pulse stimuli, a set of 11 successive trials of increasing two-second long square current steps. Traces show action potential firing in the control situation (top, black) and under the effects of menthol 250 μM (bottom, red). The action potential amplitude drop rate (B) was obtained from each corresponding current step for both conditions (1) the amplitude drop rates for each condition were averaged and plotted (2) (n = 9 average ± S.E.; p < 0.005 assessed by Student's t-test). Further analysis was performed on the last action potential of each of the 11 trials per condition (C1). These features were plotted against their corresponding trials, for both conditions (C 2) (average ± S.E.; n = 9). Ramp stimuli (D1) was performed providing a measure for the action potential threshold (D2, Top) (p < 0.005; assessed by Student's t-test) and the action potential amplitude drop rate (D2, Bottom) (p < 0.05; assessed by Student's t-test) plotted for both conditions (average ± S.E.; n = 9).

Figure 3. Analysis of menthol 250 μM effects on neural activity through current stimulation.

The recordings of I/V analysis set of stimuli (A) provided voltage values (top traces) at peak and at steady state for control (black) and in the presence of menthol 250 μM (red; circle for peak voltage values and square for steady state.) at each level of current injected (bottom traces). Data was plotted for each cell and input resistance was obtained from both voltage levels for both conditions (B) by linear fit. When compared, (C) the input resistance at peak voltage and at steady state show no statistical difference between control (black) and in the presence of menthol 250 μM (red) (n = 9 average ± S.E.; assessed by Student's t-test). Action potential waveform analysis features, amplitude and width, were obtained from high sampling (20 kHz) voltage traces (D top traces) from control (black) and menthol 250 μM (red) conditions while applying square current pulses (bottom traces). Values were plotted and compared (E) presenting no statistical difference (n = 9 average ± S.E.; assessed by Student's t-test).

Taken together, these data show that menthol exerts a general dampening effect on neural activity. They also show that this effect is voltage and time-dependent. The data collected for capsaicin, eugenol, menthol and icilin were qualitatively similar, although exact parameter values varied from compound to compound (Table 1). By contrast, AITC produced no significant effect, and cinnamaldehyde affected more features (i.e.: input resistance and AP width) (Table 1). A control study using slices from lateral amygdala showed no major differences compared to cortical slices (data not shown). A negative control using aCSF + DMSO showed no significant difference with respect to aCSF only (data not shown).

Table 1. Analyzed features of the effect of different TRP ligands in the electrophysological properties in S1 L5 pyramidal neurons.

| APDR p (μV/pA) | Lp # AP (nmbr) | APDR r (μV/pA) | Thres (mV) | AP Amp (mV) | AP Width (ms) | IR peak (MΩ) | IR s.s. (MΩ) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | −0.41 ± 0.08 | 37.2 ± 2.2 | −28.2 ± 2.9 | −41.8 ± 1.4 | 92.3 ± 2.6 | 1.22 ± 0.08 | 97.0 ± 8.2 | 74.7 ± 6.6 | |

| Mntl | −2.02 ± 0.32 | 13.6 ± 4.3 | −69.4 ± 7.5 | −36.9 ± 1.4 | 89.3 ± 2.5 | 1.22 ± 0.08 | 96.0 ± 9.2 | 74.0 ± 7.2 | |

| t-test | 0.0009 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.00003 | 0.004 | 0.485 | 0.349 | 0.368 | 9 |

| Ctrl | −0.34 ± 0.17 | 40.0 ± 4.5 | −20.1 ± 2.6 | −37.1 ± 1.4 | 91.6 ± 1.7 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 74.9 ± 8.3 | 56.2 ± 7.5 | |

| Icln | −1.18 ± 0.37 | 23.9 ± 7.1 | −32.2 ± 6.0 | −32.9 ± 2.0 | 87.9 ± 2.0 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 65.1 ± 9.3 | 52.3 ± 9.3 | |

| t-test | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.085 | 0.015 | 0.137 | 7 |

| Ctrl | −0.02 ± 0.01 | 41.8 ± 1.6 | 3.4 ± 2.4 | −43.2 ± 1.9 | 73.8 ± 4.7 | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 84.4 ± 7.3 | 70.2 ± 6.4 | |

| Cpcn | −0.78 ± 0.23 | 9.8 ± 4.4 | −29.5 ± 10.0 | −30.3 ± 3.3 | 72.5 ± 2.1 | 1.37 ± 0.14 | 87.4 ± 9.1 | 72.4 ± 7.6 | |

| t-test | 0.099 | 0.0003 | 0.058 | 0.076 | 0.387 | 0.211 | 0.335 | 0.363 | 5 |

| Ctrl | −0.38 ± 0.07 | 54.0 ± 2.6 | −23.8 ± 3.5 | −41.8 ± 0.6 | 81.0 ± 1.7 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 56.5 ± 3.2 | 44.2 ± 3.18 | |

| Egnl | −3.79 ± 1.21 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | −52.6 ± 17.4 | −30.8 ± 1.2 | 78.8 ± 1.9 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 49.8 ± 3.1 | 41.3 ± 3.3 | |

| t-test | 0.106 | 0.000001 | 0.079 | 0.005 | 0.180 | 0.052 | 0.0134 | 0.141 | 7 |

| Ctrl | −0.28 ± 0.07 | 51.3 ± 3.2 | −17.4 ± 4.2 | −42.3 ± 0.7 | 73.1 ± 2.6 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 64.6 ± 2.5 | 51.1 ± 2.1 | |

| Cnld | −0.53 ± 0.09 | 26.9 ± 3.5 | −26.6 ± 3.3 | −38.9 ± 0.8 | 73.1 ± 2.4 | 1.18 ± 0.04 | 76.5 ± 4.0 | 61.7 ± 3.2 | |

| t-test | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.023 | 0.00014 | 0.499 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.011 | 8 |

| Ctrl | −0.27 ± 0.13 | 41.8 ± 2.3 | −20.8 ± 4.8 | −39.6 ± 2.2 | 75.3 ± 4.2 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 74.9 ± 10.3 | 61.0 ± 9.0 | |

| AITC | −0.33 ± 0.31 | 28.3 ± 4.7 | −25.1 ± 8.1 | −41.8 ± 2.6 | 75.9 ± 4.5 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | 95.0 ± 16.3 | 84.4 ± 15.4 | |

| t-test | 0.393 | 0.003 | 0.168 | 0.008 | 0.315 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.017 | 6 |

Role of TRP channels

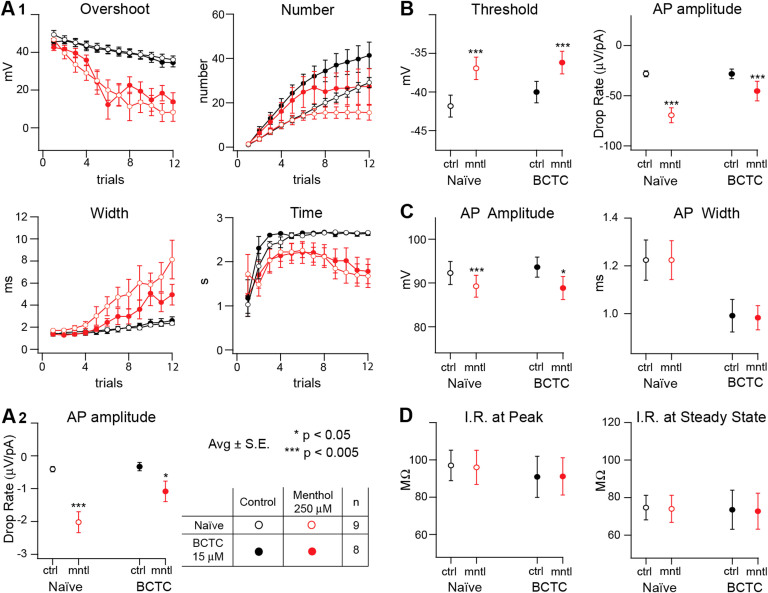

All of the AIS studied act as potent TRP channel agonists and one possible explanation for the effects described above is that AIS act directly on their corresponding TRP receptors expressed in the brain. To test this hypothesis, we investigated this possibility for menthol and icilin known to be potent agonists of TRPM8. TRPM8 ligands have been described as having the least cross reaction with other TRP channels (not the case for TRPV and TRPA1 ligands25,26), which allows for more precise control of the TRP pathway for these agonists. TRPV1 receptors have been identified in the central nervous system27,28,29 and TRPA1 as well20, but no TRPM8 has been localized in the mouse brain. The general TRP blocker, Ruthenium Red and the specific TRPV1 blocker capsaizepine on their own affected the firing behaviour of the glutamatergic neurons, rendering them more reactive (data not shown). This made them unsuitable for a clear evaluation of a possible participation of TRP channels when exposed to AIS. BCTC a specific TRPM8 blocker, showed little or no effect on the parameter measured by our electrophysiological protocol (Fig 4, Table 2) when compared to control situation.

Figure 4. Plotted features obtained from S1 L5 pyramidal neurons through voltage recordings in naïve conditions ( ) or under the presence of the TRPM8 channel blocker BCTC 15 μM (

) or under the presence of the TRPM8 channel blocker BCTC 15 μM ( ).

).

The extracted features are obtained from different types of stimulation protocols performed on control (black) and under the effect of menthol 250 μM (red). Firing pattern features from successive incremental current square pulses are plotted and compared (A). Last AP analysis (A1) shows little or no difference on the effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red), whether if it is measured in the absence ( ; n = 9) or in the presence of BCTC 15 μM (

; n = 9) or in the presence of BCTC 15 μM ( ; n = 8) (average ± S.E.). A similar situation can be observed in the AP drop rate slope measured (A2; average ± S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). Parameters obtained from incremental current ramp stimulation are plotted (B). The effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red) on the threshold (B, left) was not blocked by BCTC 15 μM (

; n = 8) (average ± S.E.). A similar situation can be observed in the AP drop rate slope measured (A2; average ± S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). Parameters obtained from incremental current ramp stimulation are plotted (B). The effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red) on the threshold (B, left) was not blocked by BCTC 15 μM ( ; n = 8 Average ± S.E. * p < 0.05, estimated by Student's t test). On the action potential amplitude drop rate (B, right) the effect of menthol 250 μM (red) can be observed in naïve conditions (

; n = 8 Average ± S.E. * p < 0.05, estimated by Student's t test). On the action potential amplitude drop rate (B, right) the effect of menthol 250 μM (red) can be observed in naïve conditions ( ; n = 9) but stops being statistically significant in the presence of BCTC 15 μM (

; n = 9) but stops being statistically significant in the presence of BCTC 15 μM ( ; n = 8) (average ± S.E.; *** p< 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). The parameters that describe the action potential wave-form are plotted (C) and compared. The lack of effect produced by menthol (red) on the AP amplitude (left) and on the width (right) persists in naïve conditions (

; n = 8) (average ± S.E.; *** p< 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). The parameters that describe the action potential wave-form are plotted (C) and compared. The lack of effect produced by menthol (red) on the AP amplitude (left) and on the width (right) persists in naïve conditions ( ; n = 9) and in the presence of BCTC (

; n = 9) and in the presence of BCTC ( ; n = 8; Average ± S.E.; estimated by Student's t test). However, the blocker seems to have some effect on the width. The input resistance values were extracted from I/V analysis and plotted (D) for voltage at peak (left) and at steady state (right). For each case the resistance appears to remain invariant for all conditions (estimated by Student's t test).

; n = 8; Average ± S.E.; estimated by Student's t test). However, the blocker seems to have some effect on the width. The input resistance values were extracted from I/V analysis and plotted (D) for voltage at peak (left) and at steady state (right). For each case the resistance appears to remain invariant for all conditions (estimated by Student's t test).

Table 2. Analyzed features of the effect of different TRPM8 ligands in the electrophysological properties in S1 L5 pyramidal neurons in the presence and absence of a TRPM8 receptor blocker (BCTC 15 μM).

| APDR p (μV/pA) | Lp # AP (nmbr) | APDR r (μV/pA) | Thres (mV) | AP Amp (mV) | AP Width (ms) | IR peak (MΩ) | IR s.s. (MΩ) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | −0.41 ± 0.08 | 37.2 ± 2.2 | −28.2 ± 2.9 | −41.8 ± 1.4 | 92.3 ± 2.6 | 1.22 ± 0.08 | 97.0 ± 8.2 | 74.7 ± 6.6 | |

| Mntl | −2.02 ± 0.32 | 13.6 ± 4.33 | −69.4 ± 7.5 | −36.9 ± 1.4 | 89.3 ± 2.5 | 1.22 ± 0.08 | 96.0 ± 9.1 | 74.0 ± 7.2 | |

| t-test | 0.0009 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.00003 | 0.004 | 0.485 | 0.349 | 0.368 | 9 |

| BCTC | −0.33 ± 0.12 | 44.0 ± 7.1 | −28.2 ± 4.6 | −40.0 ± 1.3 | 93.6 ± 2.2 | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 90.9 ± 10.4 | 73.5 ± 9.8 | |

| BCTC + Mntl | −1.08 ± 0.29 | 24.5 ± 8.9 | −45.2 ± 9.2 | −36.2 ± 1.4 | 88.9 ± 2.5 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 91.2 ± 9.4 | 72.8 ± 9.0 | |

| t-test | 0.021 | 0.042 | 0.009 | 0.0001 | 0.039 | 0.397 | 0.488 | 0.445 | 8 |

| Ctrl | −0.34 ± 0.17 | 40.0 ± 4.5 | −20.1 ± 2.6 | −37.1 ± 1.4 | 91.6 ± 1.7 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 74.9 ± 8.3 | 56.2 ± 7.5 | |

| Icln | −1.18 ± 0.37 | 23.9 ± 7.1 | −32.2 ± 6.0 | −32.9 ± 2.0 | 87.9 ± 2.0 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 65.1 ± 9.3 | 52.3 ± 9.3 | |

| t-test | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.085 | 0.015 | 0.137 | 7 |

| BCTC | −0.27 ± 0.05 | 48.3 ± 4.1 | −18.6 ± 4.3 | −40.8 ± 1.2 | 93.9 ± 2.5 | 0.98 ± 0.07 | 68.1 ± 7.5 | 52.3 ± 6.7 | |

| BCTC + Icln | −0.66 ± 0.21 | 29.8 ± 5.8 | −20.3 ± 5.5 | −38.2 ± 1.1 | 93.4 ± 3.4 | 1.03 ± 0.08 | 69.3 ± 8.2 | 53.2 ± 7.9 | |

| t-test | 0.043 | 0.011 | 0.216 | 0.078 | 0.399 | 0.020 | 0.360 | 0.361 | 8 |

The first set of experiments was performed with BCTC in S1 L5 pyramidal neurons (n = 16). We were able to observe the same qualitative effects as in the previous study (Table 2). Menthol showed qualitatively the same effect in the absence and in the presence of BCTC 15 μM (Fig 4). Menthol had no measurable effect on the wave form of APs or on input resistance (Fig 4C and D respectively). However, even in the presence of the blocker, perfusion with menthol was associated with variations in the last AP when the neuron was stimulated with successively increasing steps of square current pulses (Fig 4A1). A correlation was also observed between the presence of the AIS and with a faster drop rate of AP amplitude when measured in square pulses stimulations or increasing ramp (Fig 4A2 and 4B right, respectively) as well as with higher firing thresholds (Fig 4B left). Results for icilin were qualitatively similar (Table 2). These results imply that the dampening effects of menthol are not due, or at least not exclusively due, to their effect on TRPM8. Similar results were observed in slices from lateral amygdala.

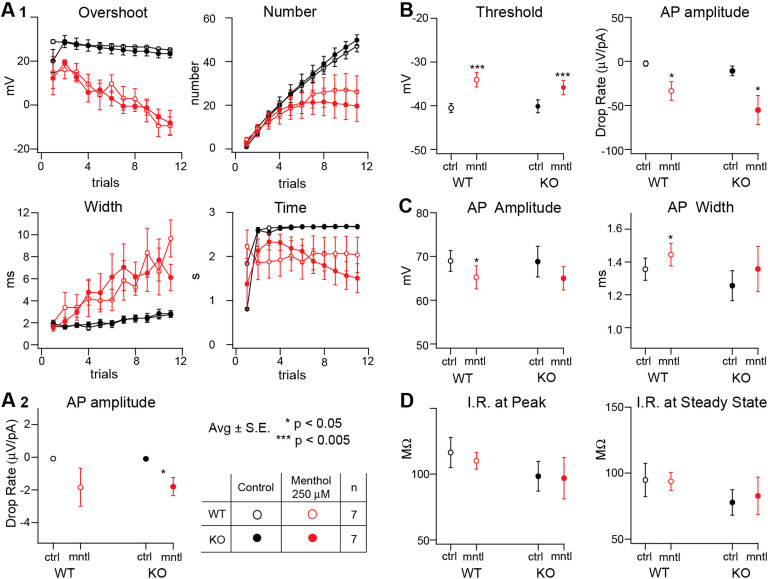

Given that some of the observed effects of the AIS were weaker in the presence of the blocker (Table 3), we repeated the study with TRPM8 ligands using TRPM8 KO mice (n = 14). As a control, the recordings were repeated on WT litter mates (n = 15) (Table 3). A set of voltage traces in response to the different types of stimuli of a single recording of a TRPM8 KO mouse are shown in the control, while applying menthol 250 μM and in washout conditions (Fig 5). The effect of the AIS on the APs at high depolarization levels is evident. A more detailed analysis of the features obtained with menthol 250 μM perfusion for TRPM8 KO and WT litter mates was plotted (Fig 6). There was little or no difference between KO and WT. The AIS effect remained mostly the same. Similar activity was observed for icilin at 50 μM (Table 3). We conclude that the observed effects of menthol and icilin are independent of their action on TRPM8.

Table 3. Analyzed features of the effect of different TRPM8 ligands in the electrophysological properties in S1 L5 pyramidal neurons in TRPM8 KO and WT mice.

| APDR p (μV/pA) | Lp # AP (nmbr) | APDR r (μV/pA) | Thres (mV) | AP Amp (mV) | AP Width (ms) | IR peak (MΩ) | IR s.s. (MΩ) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt Ctrl | −0.08 ± 0.02 | 47.0 ± 2.6 | −2.4 ± 3.0 | −40.5 ± 1.0 | 69.0 ± 2.4 | 1.36 ± 0.07 | 116.4 ± 11.5 | 94.8 ± 12.6 | |

| wt Mntl | −1.83 ± 1.16 | 21.7 ± 7.5 | −33.6 ± 10.6 | −34.1 ± 1.6 | 65.2 ± 2.6 | 1.44 ± 0.07 | 110.1 ± 6.4 | 93.8 ± 6.7 | |

| t-test | 0.096 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.035 | 0.047 | 0.304 | 0.469 | 7 |

| KO Ctrl | −0.09 ± 0.08 | 49.9 ± 2.4 | −10.8 ± 5.4 | −40.2 ± 1.5 | 68.8 ± 3.5 | 1.26 ± 0.09 | 98.4 ± 11.2 | 77.8 ± 9.7 | |

| KO Mntl | −1.80 ± 0.56 | 19.7 ± 7.2 | −55.4 ± 16.6 | −35.8 ± 1.6 | 65.0 ± 2.7 | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 96.9 ± 15.7 | 82.8 ± 14.2 | |

| t-test | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.135 | 0.101 | 0.429 | 0.270 | 7 |

| ± | |||||||||

| wt Ctrl | −0.17 ± 0.02 | 48.4 ± 3.0 | −19.5 ± 3.9 | −42.9 ± 0.9 | 76.1 ± 2.1 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 71.4 ± 4.5 | 54.9 ± 3.5 | |

| wt Icln | −1.07 ± 0.37 | 38.8 ± 6.8 | −27.1 ± 3.6 | −41.3 ± 0.9 | 76.1 ± 1.8 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 62.5 ± 6.7 | 49.9 ± 5.4 | |

| t-test | 0.022 | 0.111 | 0.141 | 0.102 | 0.495 | 0.399 | 0.019 | 0.092 | 8 |

| KO Ctrl | −0.27 ± 0.04 | 46.3 ± 1.6 | −21.3 ± 4.7 | −41.7 ± 0.8 | 73.8 ± 2.2 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 74.2 ± 7.3 | 60.4 ± 5.5 | |

| KO Icln | −0.53 ± 0.09 | 43.0 ± 4.9 | −25.1 ± 5.7 | −41.5 ± 1.3 | 73.3 ± 2.2 | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 61.1 ± 5.4 | 50.8 ± 4.2 | |

| t-test | 0.008 | 0.271 | 0.124 | 0.369 | 0.364 | 0.185 | 0.016 | 0.025 | 7 |

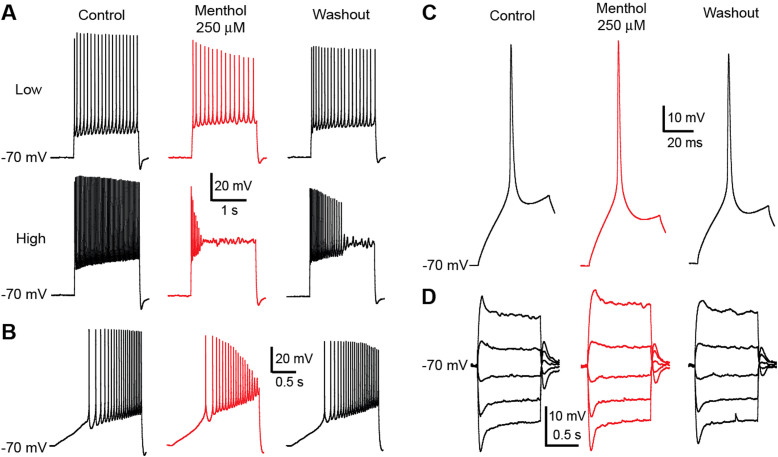

Figure 5. Voltage recordings from a single L5 pyramidal neuron of a C57BL6/J TRPM8 KO mouse primary somatosensory cortex.

The response corresponds to different current stimuli in control (left), menthol 250 μM (red, center) and washout (right) conditions. Voltage traces of suprathreshold square pulse stimuli (A) with low current (top row) and high current stimulation (bottom row) in all three conditions. Firing pattern is strongly affected by the presence of menthol 250 μM (A, red, center) especially at high depolarization levels. Firing behaviour is partly recovered after washout (A, right). Voltage response to an increasingly depolarizing ramp (B) from subthreshold to suprathreshold values show a difference between control (left) and menthol 250 μM (red, center) conditions. Firing pattern is partly recovered on the washout (right). Voltage traces corresponding the AP wave-form (C) and to I/V Analysis (D) show no difference between control (left) and menthol 250 μM (red, center) conditions.

Figure 6. Plotted features obtained from S1 L5 pyramidal neurons through voltage recordings in wild type animals ( ) or in a TRPM8 KO strain (

) or in a TRPM8 KO strain ( ).

).

The extracted features are obtained from different types of stimulation protocols performed on control (black) and under the effect of menthol 250 μM (red).Firing pattern features from successive incremental current square pulses are plotted and compared (A). Last AP analysis (A1) shows little or no difference on the effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red), whether if it is measured in wild type ( ; n = 7) or in TRPM8 KO animals (

; n = 7) or in TRPM8 KO animals ( ; n = 7) (average ± S.E.). Similar situation can be observed in the AP drop rate slope measured (A2, average ± S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). Parameters obtained from incremental current ramp stimulation are plotted (B). The effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red) on the threshold (B, left) and on the action potential amplitude drop rate (B, right) is present whether obtained from wt (

; n = 7) (average ± S.E.). Similar situation can be observed in the AP drop rate slope measured (A2, average ± S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). Parameters obtained from incremental current ramp stimulation are plotted (B). The effect produced by menthol 250 μM (red) on the threshold (B, left) and on the action potential amplitude drop rate (B, right) is present whether obtained from wt ( ; n = 7) or TRPM8 KO (

; n = 7) or TRPM8 KO ( ; n = 7) animals (average±S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). The parameters that describe the action potential wave-form are plotted (C) and compared. The lack of effect produced by menthol (red) on the AP amplitude (C, left) and on the width (C, right) persists in wt (

; n = 7) animals (average±S.E.; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, estimated by Student's t test). The parameters that describe the action potential wave-form are plotted (C) and compared. The lack of effect produced by menthol (red) on the AP amplitude (C, left) and on the width (C, right) persists in wt ( ; n = 7) and in TRPM8 KO animals (

; n = 7) and in TRPM8 KO animals ( ; n = 7) (average ± S.E.; estimated by Student's t test). The input resistance values were extracted from I/V analysis and plotted (D) for voltage at peak (D, left) and at steady state (D, right). For each case the resistance appears to remain invariant for all conditions (estimated by Student's t test).

; n = 7) (average ± S.E.; estimated by Student's t test). The input resistance values were extracted from I/V analysis and plotted (D) for voltage at peak (D, left) and at steady state (D, right). For each case the resistance appears to remain invariant for all conditions (estimated by Student's t test).

Abolition of bursting behaviour in an in vitro model of epilepsy

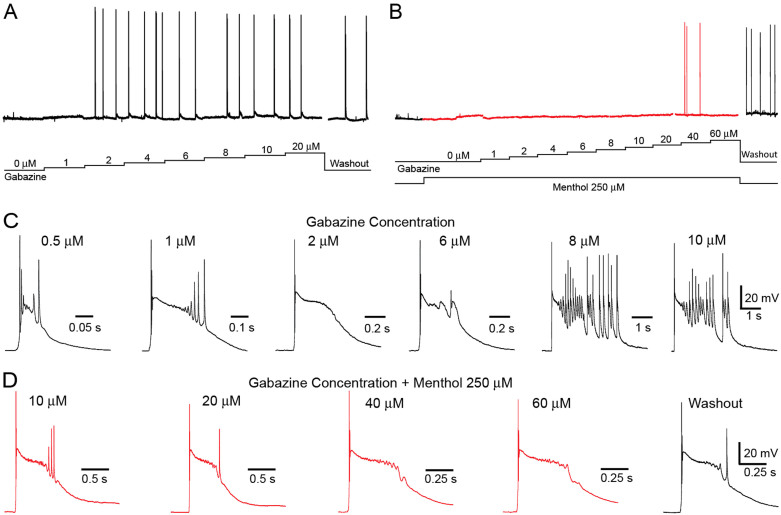

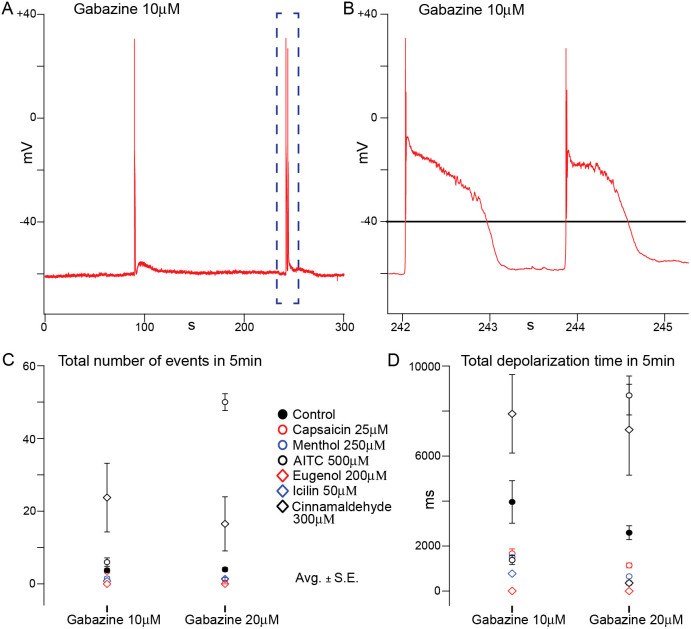

The dampening effect of the selected AIS on neuron firing provides a possible explanation for previous observations that some AIS inhibit epileptic-like bursting behaviour in slices. To investigate this effect further we used an in vitro model of epilepsy using a GABAA blocker30. We found that in the absence of AIS (the first phase of our experimental procedure), doses of gabazine of 1 μM and higher reliably induced rapid bursting behaviour (Fig 7A and 7C). However, perfusion of cortical slices with capsaicin, eugenol, menthol or icilin, diminished or abolished bursting with lower doses of gabazine and drastically reduced bursting at higher ones. The effect for menthol 250 μM when the bursting protocol was being performed was observed in single cell recordings (Fig 7B and 7D). Perfusion with menthol completely abolished bursting for doses of gabazine <10.0 μM. Washout partially restored the original bursting behaviour underlining that the abolition of bursting is due to the action of menthol. Repetition of the protocol with capsaicin, eugenol and icilin, induced qualitatively similar effects. Cinnamaldehyde and AITC on the other hand produced an inverse effect leading to an intensification of bursting activity (Fig 8, Table 4 and 5).

Figure 7. Menthol prevents seizure-like bursts in the neocortex.

Voltage recordings of layer 5 pyramidal neurons of mouse primary somatosensory cortex while applying gabazine through increasing concentration steps (A). Elicited bursts increase in duration and the number of APs elicited as the concentration of gabazine becomes higher (C). The increasing concentrations steps of gabazine protocol are repeated while permanently applying menthol 250 μM (red). In order to obtain bursts higher gabazine is required (B) and the duration as well as the number of APs elicited decrease (D).

Figure 8. Voltage recordings in the absence (control) or in the presence of the different AIS were obtained while Gabazine was applied in an incremental manner through 5 min steps.

AP bursts were spontaneously generated (A). AP bursts were analyzed and quantified for two different concentrations of Gabazine (10 μM and 20 μM), by arbitrarily placing a depolarization limit at −40 mV (B). Data was plotted as total number of events (C), and total duration of the depolarized phase (D).

Table 4. Total number of events in 5 min in the presence of the different AIS, with 10 μM or 20 μM of Gabazine Avg. ± S.E.

| N | Gab 10 μM | t-test | Gab 20 μM | t-test | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.75 ± 0.48 | 4.00 ± 0.58 | 4 | ||

| Capsaicin 25 μM | 3.40 ± 0.25 | 0.273 | 1.2 ± 0.49 | 0.006 | 5 |

| Eugenol 200 μM | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.003 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.006 | 3 |

| Menthol 250 μM | 1.50 ± 0.5 | 0.009 | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 0.002 | 4 |

| Icilin 50 μM | 0.80 ± 0.49 | 0.002 | 1.40 ± 0.40 | 0.004 | 3 |

| AITC 500 μM | 6.00 ± 1.15 | 0.05 | 50.00 ± 2.31 | 0.00002 | 3 |

| Cinnamaldehyde 300 μM | 23.75 ± 9.44 | 0.039 | 16.50 ± 7.42 | 0.107 | 4 |

Table 5. Total time of depolarized membrane potential (>−40 mV) in 5 min with 10 μM or 20 μM of Gabazine, in the presence of the different AIS. Avg. ± S.E.

| Duration (s) | Gab 10 μM | t-test | Gab 20 μM | t-test | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.96 ± 0.95 | 2.59 ± 0.11 | 4 | ||

| Capsaicin 25 μM | 1.67 ± 0.20 | 0.016 | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 0.0056 | 5 |

| Eugenol 200 μM | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.025 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0037 | 3 |

| Menthol 250 μM | 1.51 ± 0.09 | 0.041 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.0004 | 4 |

| Icilin 50 μM | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.043 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.0011 | 3 |

| AITC 500 μM | 1.38 ± 0.20 | 0.036 | 8.69 ± 0.87 | 0.0013 | 3 |

| Cinnamaldehyde 300 μM | 7.87 ± 1.74 | 0.048 | 7.17 ± 2.02 | 0.0573 | 4 |

Discussion

We have shown that perfusion of brain slices with capsaicin, eugenol, menthol, icilin dampens the activity of single neurons, especially when neurons are maintained in a depolarized condition. Further, we have shown that perfusion with these AIS completely or partially abolishes bursting behaviour in an in vitro model of seizure. This result is compatible with previous reports that several AIS (capsaicin21, linalool22, menthol23), inhibit epileptic-like behaviour in vivo and in vitro31.

Interestingly, several different AIS produce qualitatively similar effects both on single neurons and on larger-scale network behaviour. This suggests the existence of a common mechanism of action that could be shared by other AIS and some of their synthetic analogues. On the basis of the parameters analyzed, the effects elicited on glutamatergic neurons appear to be more similar between TRPV1/3 and TRPM8 ligands than those produced by TRPA1 one.

The effect observed could be described as a drop in the probability of generating subsequent APs. If the neurons, in the presence of the AIS, were stimulated by a square pulse from holding membrane potential (−70 mV) to supra threshold values, they normally elicited at least one AP. The probability of observing subsequent APs while the depolarization lasted depended on the voltage (the more depolarized, the lower the probability) and how long it was maintained (the longer the neuron was depolarized, the probability also lowered). This contrasted with the fact that once the neuron's voltage was brought back to −70 mV the condition was somehow reset. Thus, when the neuron was again depolarized, it was able to fire again. (Fig 2). When stimulated with a constant and gradual increase of current, threshold level became more depolarized in the presence of the AIS. In some cases (TRPV1/3 ligands) no AP was observed. These behaviours could indicate that AIS affect the inactivation phase in the fast sodium currents.

Based on the results obtained on the TRPM8 KO animals, our study shows that the action of menthol and icilin on neural activity is independent of their effect on TRPM8. Mechanisms of action proposed by other authors include enhancement of the currents generated by low concentrations of GABAA, direct activation of the GABAA receptor3,23 and longer-term neuroprotective effects (decreased oxidation and apoptosis, decreased concentration of the cytokines IL-1b and TNF-a)32,33. However, our study shows that menthol and icilin are effective even when the GABAA receptor is blocked by gabazine. It also shows that the effects of AIS are immediate, and therefore independent of longer-term neuroprotective mechanisms. This suggests the presence of an additional independent mechanism of action.

The effects of AIS appear to involve voltage and timing-dependent modulation of the sodium currents responsible for the generation of APs. Previous work on the peripheral nervous system (PNS) has shown that some AIS present analgesic properties when applied topically. In the case of menthol3, the mechanism of the analgesia has been related to modulation of sodium currents3,34,35,36 and calcium currents. When superfused with menthol3 dorsal neurons presented a similar effect on their firing pattern in a dose-dependent manner. Our results suggest that the same or a similar mechanism is present in the brain. This mechanism appears to be independent of TRP or GABAA receptors.

Given that several different AIS produce qualitatively similar effects, we predict that as well as binding to the specific TRP channel with which they are usually associated (e.g. TRPM8 for menthol and icilin) these compounds act on other sodium/calcium channels in the same superfamily of ion channels, perhaps by extending their physiological refractory period. If this is true, AIS modulate the positive feedback loop through which sodium currents depolarize the cell, and generate APs affecting the recovery time of these currents.

An agent that selectively dampened neural activity in highly depolarized neurons could have clinical applications. Excitotoxicity (death or damage to neurons due to excessive stimulation) is associated with a broad range of conditions including spinal cord injury, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and a broad range of neurodegenerative diseases. Our own results combined with results from other groups mentioned before21,22,23,31 provide a preliminary proof of concept that several AIS display the desired properties. AIS' long history of safe use in food and traditional medicine provides an additional favourable indication for clinical applications. Finally, the fact that several different AIS have qualitatively similar effects on neural activity suggests that it may be possible to design synthetic spice analogues with pharmacological properties superior to those of their natural counterparts.

In our study, AIS were administered via perfusion, providing no indication of whether AIS can cross the blood-brain barrier. However, Zhang et al23 report that menthol has an anti-epileptic effect, not only in culture but also when administered through intraperitoneal (i.p) injection. Similarly, De Almeida et al22 report that i.p. injection of AIS (linalool, TRPM8 ligand) present in the leaves of Cissus sicyoides can inhibit epileptic activity. This is apparent evidence that at least some AIS can cross the brain barrier by exerting a similar effect to the one observed in the present study, and for those AIS tested, that they are not toxic in in vivo conditions21,22,23,33.

More research is needed to study whether AIS are effective in models of disease that are more realistic than the admittedly artificial (in vitro) models we have used in this study. Proof of possible clinical effectiveness, will require studies of optimal dosage and evaluation of alternative modes of administration.

Finally, more work is needed to understand the mechanism or mechanisms through which AIS modulate neural activity. It might be possible that these AIS interact directly with the sodium channels that are responsible for generating APs, or it might be that the size of these molecules and their lipophilicity affect the lipid bilayer of neurons in a way that disrupts their inactivation tau. We infer that the analgesia effect already observed in the literature on the PNS and the antiepileptic effect tested with some of these AIS might be two sides of the same mechanism.

Methods

Spices

The effects of the active ingredients of five naturally occurring spices (capsaicin - red chili; eugenol - cloves; cinnamaldehyde - cinnamon; menthol - mint; allyl isothiocianate - wasabi; radish; and mustard) and one artificial spice analog (icilin) were investigated. Capsaicin4 and eugenol9 bind to TRPV1, menthol15 and icilin17 bind to TRPM8, and cinnamaldehyde and allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) bind to TRPA120. To improve solubility, the compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to form a stock solution, which does not affect electrophysiological properties37.

Capsaicin, icilin, eugenol, menthol and cinnamaldehyde were obtained from Sigma - Aldrich. AITC was obtained from Spectrum Chemical MFG. Corp.

Cortical Preparations

Parasagittal cortical preparations (300 μm thick) were obtained from the primary somatosensory cortex of wild type (C57BL6/J) mice post-natal 13–18 days. All procedures were conducted in conformity with the Swiss Welfare Act and the Swiss National Institutional Guidelines on Animal Experimentation for the ethical use of animals. The project was approved by the Swiss Cantonal Veterinary Office following its ethical review by the State Committee for Animal Experimentation. All cortical preparations were cut in ice-cold aCSF (artificial cerebro-spinal fluid) with low Ca2+ and high Mg2+. Cortical preparations were then transferred to 34°C for 20 min in normal aCSF and kept at room temperature (20–22°C) before the start of recording. Normal and cutting aCSF were continuously bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The cutting aCSF contained (mM): 10 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 125 NaCl, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4. The normal aCSF contained (mM): 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 125 NaCl, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4. Both had a pH of 7.3. During recording, cortical preparations were constantly perfused with aCSF at 2 ml/min at 33°C (±1°C). All chemical compounds were obtained from Sigma – Aldrich.

Characterizing spice effects on single neurons

Characterization of single neuron activity was based on a standardized current injection and recording protocol developed in our laboratory38. The protocol records 50 parameters characterizing the response of the cell to a standardized battery of 15 electrophysiological stimuli. Individual cells are identified optically and patched in whole cell, current clamp mode using a multi-patch set-up. Administration of the complete protocol takes approximately 10 minutes. Here we focused on a subset of the parameters generated by the protocol as described in greater detail below.

Parameters for Action Potentials (AP) are measured using fast sampling (20 kHz) of a single AP, evoked by a single square pulse of current. The voltage response of the cell is characterized by gradually ramping up the input current, and recording changes in voltage, including the APs generated when the voltage passes from sub- to above threshold values. The amplitude of the elicited action potentials is plotted as a function of time. Input resistance at sub-threshold voltage is characterized by stimulating the cell with an initial current sufficient to generate a hyperpolarized voltage pulse, followed by a subsequent set of square current pulses with stepwise increasing current. By measuring the voltage at the beginning and end of each pulse (peak and steady state voltage), and plotting it against the corresponding values of current injected we can calculate the input resistances values. The time dependency of cell behaviour at above threshold voltages is characterized in terms of parameters describing changes in the amplitude of the APs generated by a depolarized cell when stimulated with a sequence of square current pulses or rate of drop in amplitude of APs, and by additional parameters describing the last AP produced by each burst (overshoot, sequence number, width, time after beginning of stimulation).

These parameters were used to characterize the effect of six AIS (capsaicin at 25 μM, eugenol at 200 μM, menthol at 250 μM, icilin at 50 μM, cinnamaldehyde at 300 μM and AITC at 500 μM), on the electrical behaviour of layer 5 pyramidal cells in parasagittal slices from the somatosensory cortex. At the beginning of each experiment, the slice was perfused with aCSF for at least 15 min. After a first administration of the stimulation protocol, the slice was perfused for a further 15 mins with a solution of a single AIS, enriched with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in aCSF at a vol/vol ratio of 1:1000. The stimulation and recording protocols were administered a second time, during continuous perfusion with AIS. The slice was then perfused with clean aCSF for a further 15 minutes (wash-out period) and the protocol was administered for a third time (only for cells that were presenting a proper seal). In between administrations of the protocol, the resting membrane potential was maintained at −70 mV.

During the study, we collected data from a total of n = 87 S1 L5 pyramidal neurons (Table 1). As a negative control, we also administered the protocol on slices perfused with aCSF and DMSO without the presence of AIS. The resulting data were compared with the baseline data for slices perfused with pure aCSF. As a second, positive control each procedure was repeated in glutamatergic neurons from lateral amygdala slices.

Probing the involvement of TRP channels

We used 4-(3-chloro-2-pyridinyl)-N-[4-(1,1-dimethylethyl)phenyl]-1-piperazine carboxamide (BCTC at 15 μM) to block TRPM8 in cortical slices. The choice of the blocker was motivated by its high binding specificity14. BCTC was dissolved in DMSO to create a stock solution, which was added to the aCSF. Slices were perfused for 10 minutes with BCTC + aCSF. We then repeated the current injection and recording protocol used in our previous single neuron studies (control condition). After addition of either menthol or icilin we repeated the protocol (experimental condition). Finally, we compared the effects of AIS in slices perfused with BCTC with the effects on naïve slices.

To validate our results, we repeated the study using a TRPM8 KO mouse (Trpm8tm1Apat/J) in a B6;129S1(FVB) background13. The results were compared with WT litter mates of the same strain with same age and sex. BCTC was obtained from BioTrends.

Testing for anti-epileptic effects

To test for putative anti-epileptic effects of AIS, we used an in vitro model of epilepsy in which cortical slices are perfused with stepwise increasing doses of gabazine (SR-95531), a GABAA receptor antagonist that blocks the action of inhibitory interneurons, up-regulating slice activity and inducing bursting behaviour reminiscent of seizure. Using this model, we injected a constant current into the neurons in whole cell current clamping mode, setting the membrane voltage to −60 mV - a subthreshold value, and measuring their response to gabazine in the absence and presence of individual AIS. At the beginning of each experiment the slice was perfused for ten minutes with a single AIS diluted in aCSF, as described previously. We then added gabazine to the aCSF, starting at a dose of 1 μM and increasing the dose in discrete steps every 5 minutes up to a maximum dose of 60.0 μM. Finally, the slice was perfused with pure aCSF (no gabazine, no AIS) for a wash-out period of at least 10 minutes. Cell firing behaviour was recorded for the whole duration of the experiment.

Data were collected from 26 S1 L5 pyramidal neurons. As a negative control, we repeated the protocol on slices perfused with aCSF and DMSO without the presence of AIS. The resulting data were compared with the baseline data for slices perfused with pure aCSF and the increasing steps of the antagonist. Gabazine was obtained from Tocris.

Author Contributions

M.P. and A.E. performed the experiments. J.M. was in charge of keeping the TRPM8 KO line and performing the PCR validation for the genetic types. M.P. wrote the main body of the manuscript, and made the tables. M.P. prepared all the figures, except for figure 7 that was prepared by A.E. M.P., A.E., J.L.C. and H.M. provided the original ideas for the manuscript. A.E., H.M., J.L.C., J.M., M.P., S.C. and S.M.G. participated in active discussions of the intellectual design of the manuscript and experiments. A.E., H.M., J.L.C., J.M., M.P., S.C. and S.M.G. reviewed and corrected the manuscript and figures.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1 supplementary

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n° 253541.

References

- Billing J. & Sherman P. W. Antimicrobial functions of spices: why some like it hot. Q. Rev. Biol. 73, 3–49 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapsell L. C. et al. Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future. Med. J. Aust. 185, S4–24 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan R. et al. Central Mechanisms of Menthol-Induced Analgesia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 343, 661–672 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J. et al. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389, 816–824 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. The TRP Superfamily of Cation Channels. Sci. Signal. 2005, re3 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K. & Montell C. TRP Channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid S. R. & Cortright D. N. in Sens. Nerves (eds. Canning, B. J. & Spina, D.) 261–281 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.-Y. & Corey D. P. TRP channels in mechanosensation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15, 350–357 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B. H. et al. Activation of vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1) by eugenol. J. Dent. Res. 82, 781–785 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L. A., Christie M. J. & Connor M. Anandamide is a partial agonist at native vanilloid receptors in acutely isolated mouse trigeminal sensory neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 137, 421–428 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Blair N. T. & Clapham D. E. Camphor Activates and Strongly Desensitizes the Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Subtype 1 Channel in a Vanilloid-Independent Mechanism. J. Neurosci. 25, 8924–8937 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara F. N., Randall A. & Gunthorpe M. J. Effects of piperine, the pungent component of black pepper, at the human vanilloid receptor (TRPV1). Br. J. Pharmacol. 144, 781–790 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A. et al. TRPM8 Is Required for Cold Sensation in Mice. Neuron 54, 371–378 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre R., Brauchi S., Madrid R. & Orio P. A Cool Channel in Cold Transduction. Physiology 26, 273–285 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier A. M. et al. A TRP Channel that Senses Cold Stimuli and Menthol. Cell 108, 705–715 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasnelli J., Albrecht J., Bryant B. & Lundstrom J. Perception of specific trigeminal chemosensory agonists. Neuroscience 189, 377–383 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFalco J., A J. Duncton M. & Emerling D. TRPM8 Biology and Medicinal Chemistry. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 11, 2237–2252 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. J. M. et al. Direct evidence for functional TRPV1/TRPA1 heteromers. Pflüg. Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 1–13 (2014) [Google Scholar]

- Salas M. M., Hargreaves K. M. & Akopian A. N. TRPA1-mediated responses in trigeminal sensory neurons: interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 1568–1578 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B., Appendino G. & Owsianik G. The transient receptor potential channel TRPA1: from gene to pathophysiology. Pflüg. Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 464, 425–458 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.-H. et al. Capsaicin prevents kainic acid-induced epileptogenesis in mice. Neurochem. Int. 58, 634–640 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida E. R. de, Rafael K. R. de O., Couto G. B. L. & Ishigami A. B. M. Anxiolytic and Anticonvulsant Effects on Mice of Flavonoids, Linalool, and alpha -Tocopherol Presents in the Extract of Leaves of Cissus sicyoides L. (Vitaceae). BioMed Res. Int. 2009 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-B. et al. A-Type GABA Receptor as a Central Target of TRPM8 Agonist Menthol. PLoS ONE 3, e3386 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A., Prabhakar M., Kumar P., Deshmukh R. & Sharma P. L. Excitotoxicity: Bridge to various triggers in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 698, 6–18 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori N. et al. Intragastric administration of allyl isothiocyanate increases carbohydrate oxidation via TRPV1 but not TRPA1 in mice. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300, R1494–R1505 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung G. et al. Activation of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 by eugenol. Neuroscience 261, 153–160 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.-X., Min J.-W., Liu Y.-Q., He X.-H. & Peng B.-W. Expression of TRPV1 in the C57BL/6 mice brain hippocampus and cortex during development. Neuroreport (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth A. et al. Expression and distribution of vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) in the adult rat brain. Mol. Brain Res. 135, 162–168 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh D. J. et al. Trpv1 Reporter Mice Reveal Highly Restricted Brain Distribution and Functional Expression in Arteriolar Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Neurosci. 31, 5067–5077 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnup S. & Stelzer A. Seizure-like activity in the disinhibited CA1 minislice of adult guinea-pigs. J. Physiol. 532, 713–730 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M., Pape H.-C., Speckmann E.-J. & Gorji A. Effect of eugenol on spreading depression and epileptiform discharges in rat neocortical and hippocampal tissues. Neuroscience 140, 743–751 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubió L., Motilva M.-J. & Romero M.-P. Recent Advances in Biologically Active Compounds in Herbs and Spices: A Review of the Most Effective Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Active Principles. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 53, 943–953 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadania M., Joshi H., Patel P. & Kulkarni V. H. Protective effect of menthol on β-amyloid peptide induced cognitive deficits in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 681, 50–54 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-Y., Mitchell J. & Wang G. K. Preferential block of inactivation-deficient Na+ currents by capsaicin reveals a non-TRPV1 receptor within the Na+ channel. Pain 127, 73–83 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J. S., Kim T. H., Lim J.-M. & Song J.-H. Effects of eugenol on Na+ currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 1243, 53–62 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onizuka S. et al. Capsaicin indirectly suppresses voltage-gated Na+ currents through TRPV1 in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Anesth. Analg. 112, 703–709 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt C., Breustedt J. M., Nöldner M., Chatterjee S. S. & Heinemann U. The antiepileptic drug losigamone decreases the persistent Na+ current in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 920, 27–31 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidhar S., Wang Y. & Markram H. Synaptic and cellular organization of layer 1 of the developing rat somatosensory cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 7; Art. 52, 1–17 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1 supplementary