Abstract

Background

Although it is legal for multiunit housing (MUH) property owners in all 50 states to prohibit smoking on their premises, including in individual units, MUH constitutes a relatively new setting to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke via voluntary smoke-free policy. This paper examines California state-funded smoke-free MUH policy campaigns between 2004 and 2010.

Methods

A cross-case analysis of 40 state-funded smoke-free MUH policy campaigns was conducted via an examination of final evaluation reports submitted to the California Tobacco Control Program.

Results

The most effective voluntary smoke-free MUH policy campaigns typically included: (1) learning the local [MUH] context, (2) finding and using a champion, (3) partnering with like-minded organisations, (4) building relationships with stakeholders, (5) collecting and using local data and (6) making a compelling case to decision makers.

Discussions

The aforementioned steps tended to be intertwined, and successfully securing voluntary smoke-free MUH policy required a strategic but flexible plan of implementation prior to entrance into the field. Campaigns designed to enhance voluntary smoke-free MUH policy adoption should underscore the economic viability of such policies during each strategic step.

Keywords: Public policy, Secondhand smoke, Priority/special populations

Introduction

Tobacco control policies have made significant advances in protecting children and non-smoking adults from secondhand smoke (SHS),1 a demonstrated source of negative health effects.2–4 Workplace smoking bans were among the first policies to reduce exposure to SHS, and have contributed to significant declines in hospitalisations and deaths from cardiac, cerebrovascular disease, and respiratory diseases including asthma and lung infection.5

Multiunit housing (MUH), such as apartment complexes and condominiums, is a new setting for policy approaches to reduce exposure to SHS.1 6–8 Smoke drifts in from outside balconies, decks and common areas, and seeps through shared ventilation, walls, crawl spaces and electrical fixtures.9 10 According to recent estimates, roughly 80 million US residents live in MUH complexes.6 7 Likewise, nearly 12 million Californians live in MUH complexes,11 including a disproportionately high number of ‘priority populations’ who have higher rates of smoking-related diseases,6 12 13 and are identified by the California Tobacco Control Program as those with the highest rates of tobacco use, including people with low incomes, ethnic/racial minorities, youth and members of the military, and who are, therefore, a priority for tobacco control efforts.14

MUH property owners in all 50 states may legally prohibit smoking on their premises, yet MUH is a relatively new setting to reduce SHS exposure via policy. Recent studies have found that the vast majority of MUH residents employ smoke-free rules in their own homes, yet many remain exposed to SHS incursions from outside their own unit space.6 7 Moreover, it has been found that children living in MUH complexes are more susceptible to involuntary SHS and had higher cotinine levels than children living in detached houses.15

Although MUH policies are a relatively new area for tobacco control policy research,1 some lessons can be gleaned from the handful of topical studies published. For example, Pizacani and colleagues16 contend that policy success of a Portland, Oregon, intervention was due to building relationships with stakeholders, collecting local data as part of presenting and shaping the educational messages, and emphasising the good business sense of adopting voluntary policy for smoke-free housing. They noted that it is this latter idea—emphasising the economic benefits of smoke-free policy—that was key in getting local policy adopted. Other studies have similarly noted the challenge of overcoming owners’ and managers’ misconceptions about policy implementation barriers,17 18 as well as the myriad legal issues concerning tenants, smokers’ rights and the adoption of smoke-free policy.17 19–21

This qualitative study examined the efforts of 40 local tobacco control campaigns in California to adopt smoke-free voluntary policies in MUH complexes. It describes the types of, and the extent to which these policies were adopted in housing used by people most likely to be affected SHS (eg, low socioeconomic status, ethnic/racial minorities and young adults). We analysed successful and unsuccessful campaigns to identify key advocacy strategies to inform future policy work in this arena.

Smoke-free multiunit housing policy context in California

In California, landlords may legally restrict smoking in apartment or condominium complexes.22 This is true for both market rate and government-assisted housing.

While California has been a vanguard in enacting local-level laws prohibiting smoking in MUH, these ordinances, which afford greater protection of residents than voluntary policies, tend to generate substantial opposition,22 and are, therefore, more difficult to adopt. Francis and colleagues8 thus propose a policy adoption continuum, where voluntary policies—those implemented by individual landlords and owners—typically provide a critical first step in the policy adoption process, effectively creating a natural stepping stone to legislative policies at the local and, ultimately, the state-wide level. Smoke-free MUH policy is relatively new, and so voluntary policies are the focus of this study.

Methods

Data

This study examines the final evaluation reports submitted by state-funded local tobacco control projects throughout California working on smoke-free MUH policy objectives for the 2004–2007 and 2007–2010 contract cycles. The majority of the agencies were local health departments, but non-profit social service agencies and community clinics were also represented.

Forty reports presented information on campaigns, and were the primary sources of data for this analysis. Six of the reports represent the work of three agencies; their success in policy adoption during the first funding period encouraged them to expand their work in MUH during the next funding period. The remaining agencies submitted one report on voluntary MUH policy during either funding period.

Each report describes intervention and evaluation activities conducted over a 3-year period. The evaluation activities described in the reports might include preobservations and postobservations of targeted MUH complexes; tenant or public opinion surveys; key informant interviews of owners and managers; confirmation of changes in written policies (eg, changes in lease agreements specifying smoke-free units); and content analyses of local media coverage of campaigns. Final reports ranged from 10 to 30 pages in length.

Qualitative analysis strategy

We employed a cross-case analysis where the goal was to develop an explanation for successful campaigns by analysing themes, patterns, similarities and differences across the campaigns,23 comparing successful with unsuccessful campaigns.

Once the relevant reports were identified, a reviewer used open coding24 to find themes, categories and patterns related to the campaign activities, and responses of the owners and managers. One researcher read each report 2–3 times, coding and making analytic notations on themes, categories, and illustrative quotes for each report. The coded themes, categories and analytic notes were the basis of a quasi-inductive, pattern-level analysis. Patterns were identified by a report writer (eg, economic concerns of owners and managers) and tested against other cases. Patterns emerged from similarities across cases or omissions. Initial categories were actively modified during the analytic process.25 For example, during the initial coding stage, ‘policy readiness’ was deemed a major theme which accounted for almost all activities carried out by the projects prior to commencement of their formal campaigns. Yet, in revisiting the data and modifying the themes, we created subsets of categories that better described the projects’ campaigns and later became a few of this study's delineated strategies (eg, ‘learning the local MUH context’; ‘finding and utilizing a ‘champion’’; ‘collecting and using local data’; etc). Similarly, individual codes and themes were sometimes expanded into larger categories in order to better clarify the intended strategy that was carried out (eg, landlords’ concerns over adopting smoke-free MUH policy derived from the following: landlords’ concerns over the legality of smoke-free MUH policy; a policy's potential negative economic ramifications; and issues related to policy enforcement). In each of these instances, and throughout the analytical process, a second researcher independently identified the same set of themes related to successful campaign strategies, confirming the initial conclusions from the cross-case analysis.

Results

Voluntary policies and settings

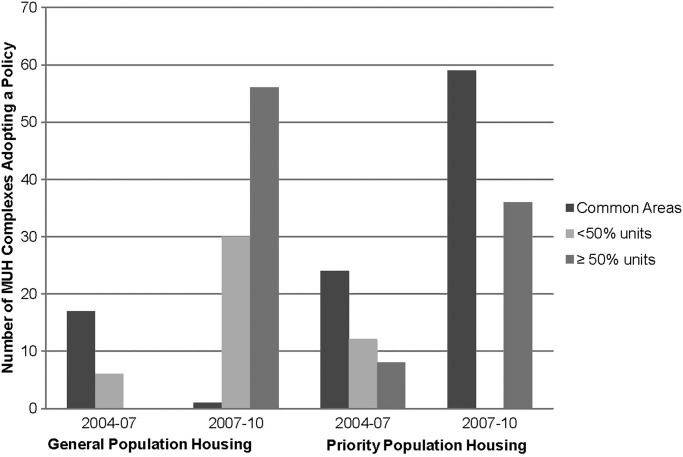

Forty campaigns sought a voluntary change in MUH policy (16 in 2004–2007 and 24 in 2007–2010). Each identified a target number of complexes to adopt a particular type of policy; some targeted apartment complexes with high numbers of priority population tenants. Successful policies varied along a continuum of stringency and varied over time and by target population (figure 1). Some campaigns sought adoption of smoke-free common areas, such as children's play areas and shared laundry facilities, which is the least stringent policy option. Other campaigns sought to allocate a proportion of apartment units as smoke-free, with changes to the leases indicating the new rules and an enforcement policy. We categorised these as fewer than 50%, or 50% or more of units in the complex as smoke-free. Three agencies achieved 100% of units as smoke-free in five complexes. Eight agencies achieved smoke-free common areas in addition to some proportion of units as smoke-free.

Figure 1.

Successful adoption of voluntary MUH smoke-free policies in California 2004–2010 by policy type and priority population.

Over time, more campaigns targeted complexes serving priority populations 14 (figure 1). Among these, the number adopting more stringent policies increased over time, but not as rapidly as campaigns targeting housing for the general population.

Four of the 40 campaigns were unable to secure the adoption of any sort of policy, and 36 adopted at least one policy. About 20% achieved policy adoption in a smaller number of complexes than their stated objective, or secured a less stringent policy (eg, shifting from adoption of 50% of units being smoke-free to adopting a policy to ensure smoke-free common areas). By the end of the 2–3-year funding periods, 249 complexes had adopted some form of voluntary smoke-free policy as a result of the 40 campaigns. The majority of these policies were devoted to smoke-free units (59%), and 55% of all policies were implemented in housing serving priority populations.

Successful advocacy strategies

Learning the local multiunit housing context

One of the keys to running an effective policy campaign was to strategise a plan of action based on local research prior to designing and launching an intervention. It was thus essential to understand local context. By local context we mean a setting's historical, political, cultural, economic and normative conditions. This could include a complex's size, estimates of the demographic breakdown of its tenants (and, perhaps, smoking behaviours), and most importantly, history of smoke-free policy on the premises, and whether a campaign may have a ‘contact’ with a decision maker at the complex. The most effective projects canvassed the targeted complexes, met with potential partners, and sought out information that would enable them to better understand the policy climate and likely opponents. In particular, reports mentioned how vital it was to gain an understanding of the owners and managers. Moreover, conducting initial observations of the grounds often provided projects with information about tenants’ smoking habits. Those projects that skipped this preparation phase often had an uphill battle in securing policy adoption.

Selecting the right target

A campaign's failure sometimes derived from the selection of complexes that were not ready for policy adoption. To maximise energies, it was important to find those who were more amenable to adopting policy.

While it may seem logical to begin with complexes open to policy adoption, final reports described cases in which projects committed themselves to complexes that were not entirely amenable to smoke-free policy. After trying to work around such resistance, one project recommended cutting their losses and moving on to more cooperative complexes:

In some cases the project found itself responding to a series of reasons why a smoke-free policy could not be adopted. Each time project staff would provide an answer to one reason, a new one was put in place. It seems likely that such managers objected to smoke-free policies for reasons they did not wish to state, instead offering more reasonable-sounding grounds for inaction. Time and resources may be better spent working with the many landlords who are genuinely interested in smoke-free policies.

Some projects selected MUH targets from resident complaints received by the health department. Unfortunately, because of the unilateral power of owners (and sometimes, managers), this method produced lacklustre results and demonstrated the importance of selecting a ‘policy-ready’ target:

We chose a [MUH] complex that had received some complaints from tenants... It was low-income housing for seniors and those with mobility impairments. After a full campaign of outreach and education and working with staff, in the end the [newly arrived] manager explained to us that smoke-free units would not be feasible. After all the time we put into it, we were devastated.

Finding and using ‘champions’

Leadership and support from a key person helped the success of campaigns. ‘Champions’ were individuals who had influence with specific complexes, or the rental housing industry—this could be a member of the area housing association, a tenant in the targeted complex, or an owner or manager who had already adopted a smoke-free policy. Champions were often able to persuade decision makers and influence outcomes. Champions came from all walks of life, and, oftentimes from a project's coalition, or else someone on the coalition knew this person and asked them to assist.

Champions also emerged as a campaign progressed. In almost all cases, hearing from ‘one of their own’ swayed those who were unsure about adopting a smoke-free policy. For example, one report described how managers of smoke-free MUH complexes became important point persons and ‘champions’ for the cause:

We brought in property managers who had already gone to battle and successfully adopted smoke-free policy. They gave their firsthand accounts of their experiences; their war stories and battle scars, and what it was like now that their complexes were smoke-free. These presentations really made a difference.

Partnering with like-minded organisations

Project personnel effectively collaborated with a variety of state and local organisations, both within and outside of tobacco control. Partnering with organisations that cared about issues that had some point of overlap benefited all parties. Partners included members of law enforcement, educators, healthcare professionals, and local chapters of national organisations, like the American Cancer Society and the American Lung Association. Furthermore, most projects acknowledged their debt to the California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) for technical assistance. The interconnectedness served many purposes. For instance, the campaign could draw on wider expertise and reach broader volunteer pools. One project director described the import of these relationships:

They say it takes a village to raise kids. Similarly, it takes a village to meet these [smoke-free MUH policy] objectives. We were fortunate to align and partner with many other like-minded organizations, and [C]TCP [the California Tobacco Control Program] is great about offering the assistance and support needed. It is not easy doing this, but working with others makes it more doable.

Building relationships with apartment landlords and tenants

Project directors commented on how crucial it was to establish meaningful relationships with apartment managers, owners, staff and tenants for the work to progress.

Personal contact and trusted relationships with key decisionmakers such as city officials, housing authorities, owners and managers and apartment association leadership was a key ingredient for the successful passage of the smoke-free/restricted smoking policies… that were adopted.

This relationship-building required consistent communication. Project personnel from the successful campaigns made frequent phone calls and repeatedly met with owners and managers, who in almost all cases were the key decision makers in the process.

The most important factor leading to the successful adoption of smoke-free policies was relationship building and providing continuous support to the property managers.

Projects also approached tenants to learn about what was happening at the complex. Project personnel presented data to residents about the harms of SHS and the advantages of smoke-free housing. Ultimately, this process frequently turned tenants into much needed allies, where they could spread the word and mobilise other tenants.

Training residents on the importance of tobacco prevention efforts and data collection activities, such as observation surveys and key informant interviews, increased local involvement and ownership of the project.

Collecting and using local data

Tenant surveys assessed the support for a proposed policy. Key informant interviews with apartment owners, managers or staff were also used. The data revealed the level of support or opposition and the potential parameters of a policy. Reports described situations in which projects began to work on a campaign for smoke-free sections within a complex, but found that tenants were interested in a completely smoke-free complex. Conversely, there were cases when the project staff pulled back on the campaign objectives when support from residents and/or decision makers was not there yet.

The information gleaned from key informant interviews of MUH personnel proved to be invaluable for the campaigns. For one, it allowed local projects to acquire an understanding of not only the contextual issues related to any one property, but also provided immediate feedback on any potential smoke-free policy. Project staff, additionally, noted that conducting interviews with the MUH personnel afforded them an opportunity to educate these folks, particularly the owners and managers on their legal rights as landlords, and the current research that demonstrated the economic viability of MUH smoke-free policy.

Tenant data was also vital and served two major purposes. For one, the data tended to show broad support for smoke-free living that could convince decision makers that residents strongly supported restricting or eliminating tobacco use in and around the complex. Two, the process of collecting data served to educate and involve tenants, giving them a stake in the matter. This often initiated groundswell support where tenants would rally around proposed policies. Some projects capitalised on this strategy, and held meetings and seminars at the complexes in an effort to provide education, discuss results of the tenant surveys, and secure and solidify tenant involvement. One project director explicitly made this point:

Program staff felt that soliciting resident buy-in would make it their policy, and therefore would make it more likely be implemented. That is, rather than being imposed from ‘outside’ these policies, if adopted, would belong to the residents themselves.

Making a compelling case to decision makers

Property owners and managers had three main concerns—often interconnected—which emerged in almost every campaign: (1) the legality of smoke-free policy, including smokers’ rights, (2) the potentially detrimental economic effects of a policy, and (3) the difficulties of enforcing the policy.17 These concerns are largely unfounded, and so it was imperative to provide decision makers with current research on the legal standing of smoke-free policy, precedent of similar policy successes, examples of effective enforcement strategies, sample lease language for rental agreements and statistics demonstrating the economic feasibility of going smoke-free. This latter point was especially crucial to apartment owners and managers because they viewed the economics of the issue as primary factor in making their decision concerning smoke-free policy. Thus, project personnel learned that ‘money talks’ with these housing entrepreneurs.

One way to maximise this impact was to offer seminar presentations and invite the entire local MUH community to attend. One report summed it up as:

Providing participants in the housing industry with the smoke-free ‘rationale’ combined with ‘how-to’ steps can significantly increase the likelihood of success in persuading rental property owners and managers to adopt smoke-free policies for their units.

Another report stated:

We found that these seminars have been extremely effective in reaching owners and managers. One seminar resulted in having two housing complexes [adopt] 100% smoke-free policy.

These meetings gave project staff the opportunity to meet people face to face, identify the industry opinion leaders, and get an idea of who to target. Several project directors commented on how this type of activity should be one of the first steps in a MUH objective in order to better learn the local MUH context, find champions and begin building relationships: ‘This [seminar] was something we should have done much earlier in the project.’

Discussion

Landlords of market rate and subsidised housing throughout the USA have the legal right to designate any or all parts of their MUH complexes as smoke-free.22 Landlords benefit from smoke-free policies due to lower renovation and upkeep costs, reduced fire insurance premiums and less staff time devoted to tobacco litter cleanup.26 Yet they still worry about the legality and enforcement of smoke-free policies, as well as its potential to drive away some current and would-be tenants who smoke. However, surveys repeatedly show that the majority of tenants have implemented smoke-free rules in their own homes6 7 and favour smoke-free housing policies—both in common or shared areas, and to a slightly lesser degree in individual units.7

This study of MUH campaigns in California revealed that successful campaigns clearly identified landlords’ misperceptions about MUH policies and provided relevant local information to educate landlords about their specific concerns. Many failures tended to be due to the fact that projects rushed into a complex without an understanding of where decision makers stood. Preliminary research to determine who the important players are and what views they (and the public) hold about the proposed policy is thus necessary.

This study identified a collection of strategies that educated landlords and led to the adoption of smoke-free MUH policy, including using local data, finding a champion and partnering with like-minded organisations. It is important to understand that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, nor do they necessarily follow chronologically. In this sense, they are separate but also interconnected, and like all policy, the conditions under which the aforementioned strategies were implemented proved vital to any resulting policy adoption (or lack thereof).

Some owners and managers opposed smoke-free policy, even when provided current information detailing its legality, ease of implementation and overall economic benefits. As a result, successful campaigns targeted complexes strategically, choosing first to work with those who expressed an early interest in exploring smoke-free policy options for their initial campaigns in order to gain traction and create the much needed groundswell, critical in local policy campaigns. This was vital in the future success of local projects and was the first step in the most successful campaigns. Obtaining an early and relatively easy first policy victory inspired initial decision makers to become ‘champions’ for future campaigns. As projects publicised policy adoption successes, it sparked interest among other complexes or jurisdictions and helped grow new interest in policy adoption. In this manner, groundswell support and successful policy adoptions led to the propagation of ever more policy adoptions, even among the most reluctant landlords. This was the case with campaigns targeting MUH serving priority populations and campaigns targeting other types of MUH.

Finally, we found that landlords were most concerned about how any potential policy would affect their profit margins. We thus recommend that local projects frame the policy argument to landlords in terms of its economic benefits, thereby emphasising the good business sense of smoke-free housing policy.16 26 When landlords and ‘champions’ could speak to their colleagues about the economic benefits, campaigns were more successful.

This study is not without its limitations. First, it relies on self-reported data. The final evaluation reports are required by the California Department of Public Health, and their quality—in scope and depth—differs widely. Second, the qualitative approach of this study and its concomitant results should be understood as a rendering of underlying reasons and motivations, as well as trends, in the MUH housing campaigns studied here rather than specific behaviours or attitudes that may be gleaned from a quantitative approach. Yet, a more systematic quantitative or mixed-methods study could be developed based on our findings. For instance, a state-wide MUH managers and/or tenant survey would significantly add to our data. Third, the data are derived from campaigns in California alone. Conditions for MUH campaigns may vary between California and other US states, where populations possibly will have been less strongly exposed to antismoking campaigns. Fourth, this study only examined voluntary policies and the strategies used to achieve policy adoption may not fully apply to legislative policies. Nevertheless, this study found evidence of a policy adoption continuum, and future research could identify the process by which the adoption of voluntary policies may help trigger legislative policies. Finally, evaluating the impact of MUH policy, in terms of reductions in SHS, as well as its health effects on tenants, would validate its public health value.

What this paper adds.

As an emerging public health issue, policy efforts have recently targeted smoke-free multiunit housing (MUH) as vital to the health and well-being of millions of adults and children globally since those who live in MUH are particularly susceptible to secondhand smoke which can drift into smoke-free units from nearby units and shared areas where smoking occurs. In California, landlords may legally restrict smoking in MUH complexes, and local projects funded by the California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) have instituted policy adoption campaigns across the state in an effort to persuade landlords to adopt voluntary smoke-free MUH policy.

Drawing on 40 policy campaign case studies, this qualitative study suggests that the most successful campaigns implemented strategic but flexible plans prior to entering the field, and typically included: (1) learning the local [MUH] context, (2) finding and using a champion, (3) partnering with like-minded organisations, (4) building relationships with stakeholders, (5) collecting and using local data, and (6) making a compelling case to decision makers. These findings serve to inform future campaign strategy in adopting voluntary smoke-free MUH policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Cathy Lemp for initiating the data gathering and assisting with some of the preliminary analyses on this topic. We would also like to thank all the project directors from the local projects that submitted the final evaluation reports used for this study. This work was supported through a contract from the California Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control Program. However, the authors were not compensated to write this article nor were any outside entities involved in any aspect of the research or the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors satisfied authorship guidelines.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hyland A, Barnoya J, Corral JE. Smoke-free air policies: past, present and future. Tob Control 2012;21:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.He J, Vupputuri S, Allen K, et al. Passive smoking and the risk of coronary heart disease–a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. N Engl J Med 1999;340:920–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glantz SA, Parmley WW. Passive smoking and heart disease. Mechanisms and risk. JAMA 1995;273:1047–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan CE, Glantz SA. Association between smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012;126:2177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King BA, Babb SD, Tynan MA, et al. National and state estimates of secondhand smoke infiltration among U.S. multiunit housing residents. Nicotine Tob Res 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Licht AS, King BA, Travers MJ, et al. Attitudes, experiences, and acceptance of smoke-free policies among US multiunit housing residents. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1868–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis JA, Abramsohn EM, Park H-Y. Policy-driven tobacco control. Tobacco Control 2010;19(Suppl 1):i16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraev TA, Adamkiewicz G, Hammond SK, et al. Indoor concentrations of nicotine in low-income, multi-unit housing: associations with smoking behaviours and housing characteristics. Tob Control 2009;18:438–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King BA, Travers MJ, Cummings KM, et al. Secondhand smoke transfer in multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:1133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Multi Housing Council. Washington D.C: 2009. http://www.nmhc.org/Content.cfm?ItemNumber=55508 (accessed 2 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking: cancer and chronic lung disease in the workplace. Atlanta, GA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.California Department of Health Services/Tobacco Control Section. Communities of excellence in tobacco control, module 3: priority populations speak about tobacco control. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services/Tobacco Control Section, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winickoff JP, Van Cleave J, Oreskovic NM. Tobacco smoke exposure and chronic conditions of childhood. Pediatrics 2010;126:e251–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizacani B, Laughter D, Menagh K, et al. Moving multiunit housing providers toward adoption of smoke-free policies. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A21 (accessed 7 Nov 2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satterlund TD, Treiber J, Cassady D. Navigating local smoke-free multi-unit housing (MUH) policy adoption. In review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.King BA, Travers MJ, Cummings KM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of smoke-free policy implementation and support among owners and managers of multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:159–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baezconde-Garbanati LA, Weich-Reushe K, Espinoza L, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among Hispanics/Latinos living in multiunit housing: exploring barriers to new policies. Am J Health Promot 2011;25(5 Suppl):S82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drach LL, Pizacani BA, Rohde KL, et al. The acceptability of comprehensive smoke-free policies to low-income tenants in subsidized housing. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:A66 (accessed 7 Nov 2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King BA, Cummings KM, Mahoney MC, et al. Multiunit housing residents’ experiences and attitudes toward smoke-free policies. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Center for Tobacco Policy & Organizing. 2009. http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/ (accessed 2 Nov 2012).

- 23.Yin RK. The case-study crisis—some answers. Admin Sci Quart 1981;26: 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Company, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong MK, Diamant AL, Zhou Q, et al. Estimates of smoking-related property costs in California multiunit housing. Am J Public Health 2012;102:490–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]