Dear Editor

Members of the Helcococcus genus are non-motile, catalase-negative, facultatively anaerobic gram-positive cocci. To date, a total of 5 species have been assigned to Helcococcus, including H. kunzii, H. ovis, H. pyogenes, H. seattlensis, and H. sueciensis; however, H. pyogenes has not yet received official taxonomic classification [1, 2]. H. kunzii has been identified as a causative pathogen of abscess, bacteremia, cellulitis, empyema, implantable cardiac device infection, osteomyelitis, prosthetic joint infection, and sebaceous cyst infection; however, H. kunzii-associated bacteremia is not common [3,4,5,6,7]. We report a case of H. kunzii bacteremia in a patient with diabetes.

A 58-yr-old man complained of redness in his left foot with abrasions on the third and fourth toes and pain 8 days prior to admission to the emergency room. His diabetes was diagnosed 20 yr ago and he was receiving hemodialysis for treatment of end-stage renal disease. Physical examination revealed an ulcerative lesion on the dorsum and sole of his left foot. The patient had temperature of 38.0℃, blood pressure of 195/86 mm Hg, pulse of 62/min, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Laboratory investigation showed Hb of 9.1 g/dL, leukocyte count of 7.6×109/L, platelet count of 267×109/L, C-reactive protein level of 7.42 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 112 mm/hr, glucose level of 251 mg/dL, Hb A1c level of 7.1%, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine of 18/4.4 mg/dL, and total protein/albumin level of 7.4/3.2 g/dL. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left foot revealed a soft tissue abscess in the third webspace and infectious arthritis at the third and fourth metatarsophalangeal joints.

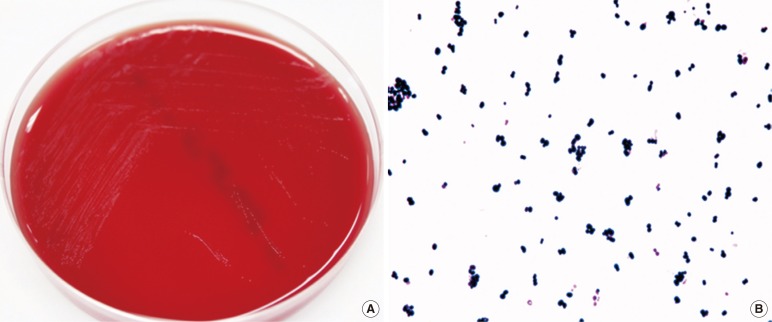

A wound swab sample and 2 sets of blood samples were collected, and the patient received empirical antibiotic therapy with intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam. Cultured swab samples were positive for Proteus mirabilis. After 48 hr of incubation, gram-positive cocci grew in 2 anaerobic blood culture bottles. The positive culture broth was streaked onto a blood agar plate (BAP) and incubated for 24 hr at 35℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, but few colonies were observed. The positive culture broth was also streaked onto a BAP and cultured anaerobically for 48 hr. Tiny gray-colored, non-hemolytic colonies were observed on the BAP cultured anaerobically; Gram staining of this microorganism revealed gram-positive cocci (Fig. 1). The isolate was positive for pyrrolidonyl arylamidase production, but was negative for leucine aminopeptidase production.

Fig. 1.

Colony and microscopic characteristics of Helcococcus kunzii. (A) Tiny, gray-colored colonies were observed on a blood agar plate after 48 hr of anaerobic incubation. (B) Gram-positive cocci from a smear of colonies obtained from the blood agar plate (×1,000).

The isolate was identified as H. kunzii by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany), which yielded a score of 2.299. In addition, Vitek2 GP system (bioMérieux, Marcy I'Etoile, France) identified the organism as either H. kunzii or Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae with equal probability. To confirm the isolate identity, 16S rRNA gene was sequenced. The 1,450 bp 16S rRNA gene sequence of the isolate shared a 99.8% identity with GenBank sequence DQ082898 (H. kunzii) and 95.6% identity with NR_027228 (H. ovis). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of the isolate was performed by Etest (AB Biodisk, Stockholm, Sweden) on BAPs incubated anaerobically for 48 hr since the isolate grew poorly at 35℃ in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Breakpoints for anaerobes published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute were used to determine susceptibility, those of erythromycin for Streptococcus spp. viridans group [8]. The isolate was susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, ertapenem, meropenem and piperacillin, but was resistant to clindamycin, erythromycin and metronidazole.

On the second day of hospitalization, the patient underwent an amputation of the third toe and debridement of the left foot. Treatment with intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam had been maintained for 3 weeks; follow-up blood cultures from the periphery on day 3 were negative, and the patient was cured without further complications.

Bloodstream infection caused by H. kunzii is extremely rare; only one patient with prior history of intravenous drug abuse has been reported [4]. This isolate was identified as H. kunzii by both 16S rRNA gene sequencing and MALDI-TOF MS. Although 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis remains the gold standard, the MALDI-TOF MS systems have also been successfully used to identify H. kunzii [7, 9]. The AST pattern indicated that the isolate was resistant to clindamycin and erythromycin. This finding corroborates previous reports on H. kunzii resistance to both of these drugs [3, 4].

In conclusion, we report the first Korean case of H. kunzii bacteremia confirmed by 16S rRNA gene analysis and MALDI-TOF MS. H. kunzii may be an opportunistic pathogen in humans, especially in patients with diabetes.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Collins MD, Facklam RR, Rodrigues UM, Ruoff KL. Phylogenetic analysis of some Aerococcus-like organisms from clinical sources: description of Helcococcus kunzii gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:425–429. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow SK, Clarridge JE., 3rd Identification and clinical significance of Helcococcus species, with description of Helcococcus seattlensis sp. nov. from a patient with urosepsis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:854–858. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03076-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chagla AH, Borczyk AA, Facklam RR, Lovgren M. Breast abscess associated with Helcococcus kunzii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2377–2379. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2377-2379.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo PC, Tse H, Wong SS, Tse CW, Fung AM, Tam DM, et al. Life-threatening invasive Helcococcus kunzii infections in intravenous-drug users and ermA-mediated erythromycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6205-6208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNicholas S, McAdam B, Flynn M, Humphreys H. The challenges of implantable cardiac device infection due to Helcococcus kunzii. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78:337–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Jorge C, Cordero J, Marin M, Esteban J. Prosthetic joint infection caused by Helcococcus kunzii. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:528–530. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01244-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sridhar S, Chan JF, Yuen KY. First report of brain abscess caused by a satelliting phenotypic variant of Helcococcus kunzii. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:370–373. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02550-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twenty-third Informational supplement, M100-S23. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois D, Segonds C, Prere MF, Marty N, Oswald E. Identification of clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates among other alpha and nonhemolytic streptococci by use of the Vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry system. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1861–1867. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03069-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]