Abstract

This article describes the establishment, over a period of ten years or so, of a multi-user, institution-wide facility for the characterization of materials and devices at the nano-scale. Emphasis is placed on the type of equipment that we have found to be most useful for our users, and the business strategy that maintains its operations. A central component of our facility is an aberration-corrected environmental transmission electron microscope and its application is summarized in the studies of plasmon energies of silver nanoparticles, the band gap of PbS quantum dots, atomic site occupancy near grain boundaries in yttria stabilized zirconia, the lithiation of silicon nanoparticles, in situ observations on carbon nanotube oxidation and the electron tomography of varicella zoster virus nucleocapsids.

Introduction

Characterization of materials has always been an integral component of the field of materials-science-engineering. In the era of “nanotechnology”, in which new materials and devices are being developed at increasingly smaller (nano) scales, this aspect is becoming ever more important. Indeed, with the advent of the new generation of aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopes (TEM's) with sub-Ångstrom resolution, the ability to establish the nature of structure, chemistry and bonding with unprecedented clarity and precision is transforming the level of information available to the nanomaterials researcher. This article describes our efforts in establishing an institution-wide, multi-user facility for nanocharacterization (the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory, SNL) and how an aberration-corrected TEM can play a central role in such an enterprise.

Background

The SNL was essentially initiated circa 2002 with the acquisition of a high resolution scanning electron microscope (SEM) and a dual-beam focused ion beam/scanning electron microscope (FIB/SEM). These complemented somewhat older generation X-ray diffraction, TEM, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and electron microprobe tools. They were consolidated into one laboratory space in 2005 and since then a major instrument has been added approximately every two years, accompanied by a professional staff member every other time. The timeline is shown in Table 1, and the current suite of capabilities in Table 2. The vast majority of purchases were made using funds provided by major units within the institution, such as the Schools and Departments whose faculty critically depend on advanced instrumentation for their research. This fundraising mode is necessitated by the increasingly high cost of the tools and the somewhat limited availability of funds at present in the USA for capital equipment for the research universities.

Table 1.

Timeline for equipment and staff acquisition at the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory

| Year | Equipment | Staff |

|---|---|---|

| Pre- 2002 | CM20 Transmission Electron Microscope X-ray Diffractometer X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer | 2.5 Professionals 1 Consulting Professor |

| 2002 | Sirion Scanning Electron Microscope Strata Focused Ion Beam/Scanning Electron Microscope | 1 Professional |

| 2005 | X-ray Diffractometers Scanning Probe Microscope | |

| 2007 | X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer Auger Electron Spectrometer | 1 Professional |

| 2009 | Tecnai F20 Transmission Electron Microscope | |

| 2010 | Titan 80-300 Environmental Transmission Electron Microscope Magellan Scanning Electron Microscope Cameca Nano Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer | 1 Professional |

| 2012 | Helios Cryo Focused Ion Beam/Scanning Electron Microscope JEOL JXA Electron Microprobe | 1 Professional |

Table 2.

Current equipment available at the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory

| Equipment | |

|---|---|

| Microscopes | FEI XL30 Sirion Scanning Electron Microscope |

| FEI Magellan 400 XHR Scanning Electron Microscope | |

| FEI Strata 235DB Dual Beam Focused Ion Beam/Scanning Electron | |

| Microscope | |

| FEI Helios NanoLab 600i Dual Beam Focused Ion Beam/Scanning | |

| Electron Microscope | |

| FEI Tecnai G2 F20 X-TWIN Transmission Electron Microscope | |

| FEI Titan 80-300 Environmental Transmission Electron Microscope | |

| JEOL JXA-8230 SuperProbe Electron Microprobe | |

| Spectrometers | PHI 700 Scanning Auger Nanoprobe |

| SSI S-Probe X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer | |

| PHI VersaProbe X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer | |

| Cameca Nano Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer 50L | |

| Diffractometers | PANalytical X'Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer |

| PANalytical X'Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer | |

| Multiwire MWL 100 Real-Time Back-Reflection Laue Camera System | |

| Bruker D8 Discover X-ray diffractometer | |

| Bruker D8 Venture X-ray diffractometer | |

| Scanning Probes | Park Systems XE-70 Scanning Probe Microscope |

| Park Systems XE-100 Scanning Probe Microscope | |

| WITec alpha500 Confocal Raman and Atomic Force Microscope |

The facility experiences widespread usage by students and faculty across the engineering and physical sciences, and increasingly in the biological community. Typical user numbers per annum are three hundred or so for the SEM's, about one hundred for the TEM's and so on. The data for the last fiscal year are given in Table 3, along with the total hours used which is typically about five thousand or so per annum for each instrument class (2000 hours is regarded as the typical USA “working week” time integrated over the year). The SNL is self-sustaining by charging user fees calculated by the laboratory annual expenses divided by the total number of hours used. Any over- or under- expenses are “carried over” each fiscal year and cannot be outside a ±15% range of the total. These figures and the approximate staff distribution are also tabulated in Table 3. For significant users, the total time for charges is capped at 24 hours per instrument in any given month so that longer, more sophisticated experiments are not penalized.

Table 3.

Financial breakdown for the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory for the 2012 academic year showing the hourly rate, hours used, income, expenses, and number of users by equipment type

| Hourly Rate [$] | Hours Used | Income [$] | Expenses | Staff | Staff FTE[a] | Number of Users | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | 45 | 4716 | 226,187 | 248,668 | 4 | 1.05 | 358 |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | 99 | 4971 | 420,923 | 405,090 | 3 | 1.8 | 104 |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) | 78 | 3711 | 249,441 | 242,904 | 2 | 0.85 | 145 |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | 30 | 4933 | 130,348 | 143,940 | 2 | 0.66 | 132 |

| Scanning Probe Microscopes (SPM) | 25 | 3520 | 69,680 | 70,870 | 2 | 0.25 | 161 |

| Surface Science Instruments (XPS, AES) | 60 | 5296 | 321,644 | 288,801 | 1 | 0.65 | 266 |

Full Time Equivalent, where one FTE corresponds to one person employed full time which is 40 hours per week in the USA.

The mission statement of the SNL is given in Table 4. We have elected to purchase the most modern instruments available which provide state-of-the-art capabilities, while ensuring a broad range of specific applications. For instance, the aberration-corrected TEM is not only a high spatial resolution imaging and diffraction machine. Rather, it has built-in additional capacity for electron energy loss and X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopies, an environmental gas chamber, electron holography and Lorentz imaging, tomography, monochromatization and specimen holders for various in-situ experiments. Further information on this and the other machines is available at the SNL website.[1] As a university, our principal role is to educate and train students and so we do not operate on a service basis, although scientific collaboration between students and professional staff is actively encouraged. Our sense is that it is the synergy of advanced capabilities and broad versatility combined with professional staff at the highest levels of accomplishment which makes the laboratory attractive to such a broad constituency.

Table 4.

The Philosophy of the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory

| Philosophy of the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory |

|---|

| -Operate a sophisticated characterization facility |

| -Develop new characterization techniques for nanomaterials |

| -Assist users to obtain high quality data |

| -Standardize nano-characterization procedures |

| -Collaborate and carry out nano-materials development research |

| -Train and educate users in the operation and interpretation of results |

It should be said at this stage that our system is one that has evolved over the last ten years or so and which works for our institution. As pointed out in a recent National Academies report on multi-user facilities in the USA, there are many successful operations with many different working models.[2] Nevertheless there are likely some guidelines here that might be considered or adopted in other laboratories.

A recent example of the application of high resolution SEM and a nano secondary ion mass spectrometer (Nano-SIMS) to study nanoparticle distributions in macrophages, Figure 1, is typical of the type of work being carried out.[3] The carbon and gold maps from the Nano-SIMS show the cellular structure and the gold core from the nanoparticles, respectively. The high resolution backscattered SEM images show the nanoparticles as bright spots. The SEM is capable of distinguishing between individual nanoparticles whereas the Nano-SIMS does not have the resolution necessary for this.

Fig. 1.

(a) carbon map and (b) gold map from NanoSIMS showing the presence of gold nanoparticles inside a macrophage with (c) SEM backscattered electron image taken after NanoSIMS acquisition showing the gold nanoparticles with higher resolution as bright dots. (d) inset showing higher magnification SEM image showing individual nanoparticles. Scale = 1 μm for (a-c) and 500 nm for (d)

Recent applications of the aberration-corrected environmental TEM

One of the cornerstone instruments in the SNL is an image aberration-corrected, monochromated, 80-300 kV environmental TEM. This has a broad range of capabilities, including energy dispersive X-ray and electron energy loss analysis, non-probe corrected STEM, holography, tomography, Lorentz imaging and remote access. Increasingly the SNL is acquiring a suite of specialized specimen holders for in-situ capability such as heating, cooling, tomography, electrical biasing with heating, liquid cell with electrical biasing, etc. Accordingly, there is an extensive user base, embracing multiple different disciplines such as materials science, mechanical engineering, electrical and chemical engineering, physics and applied physics, radiology, pediatrics, infectious disease, structural biology, etc. This instrument is therefore not dedicated to one specific area of application and must be maintained to cover all of these research areas. Some recent publications serve to illustrate this wide variety of usage.[4-8,10-11,14-15]

The monochromator capability probably represents the greatest amount of recent experimentation. With energy resolution in the 0.1-0.2 eV range, both the shape of atomic core level energy losses and low energy loss regime (conventionally < 50 eV) are readily accessible. Thus Scholl et al. clearly showed that the plasmon resonance energy of progressively smaller silver nanoparticles with sub 5 nm sizes (at around 3 eV) increases much more than has been theoretically predicted classically, requiring modifications using quantum theory to account for this new data.[4] Likewise “quantum tunneling” as nanoparticle separation becomes smaller (eg. down to 1-2 nm) can be analyzed.[5] Jung et al. studied the variation of band gap energies as a function of position across PbS quantum dots in the 8-20 nm size range, clearly establishing both that the band gap increases as expected with smaller quantum dot sizes, compared to the bulk value of 0.41 eV, but also that the band gap varies by about 20% across dome-shaped particles being greater at the periphery, Figure 2.[6] This latter work also benefitted from the 80 kV accelerating voltage capability to remove Čerenkov radiation from obscuring the bandgap measurement data.

Fig. 2.

(a) High angle annular STEM dark field image of a PbS quantum dot on 8 nm thick amorphous silica film with low loss electron energy loss spectra (c) (with zero loss peak subtracted) acquired at each circle showing the shift in bandgap with nanoparticle thickness also plotted (b) vs. position across the nanoparticle. The nanoparticle edges exhibit larger bandgaps due to stronger quantum confinement. (courtesy of Dr. H.J. Jung)

An et al.[7-8] utilized the negative spherical aberration imaging mode (NCSI) of the image corrector[9] to study oxygen site occupancy in yttria-stabilized zirconia used for fuel cell applications. Notably they showed that the oxygen content is much lower near grain boundaries, or rather that the oxygen vacancy concentration is higher in this vicinity. These observations could account for higher oxide ion incorporation at the surface grain boundaries of the cathode which would allow the cells to be more effective and useful at lower operating temperatures.[10]

McDowell et al.[11-12] employed the electrical biasing holder with heating capability in the aberration-corrected TEM to investigate the lithiation and de-lithiation of silicon nanoparticles for lithium battery energy storage. The amorphization and expansion of crystalline silicon nanoparticles during lithiation with up to 4.4 lithium atoms per silicon[10] was readily followed in-situ in the TEM, and the cracking of larger Si particles demonstrated and analyzed theoretically using mechanics calculations. Thus a critical size for the Si nanoparticles to withstand the lithiation cycling process was established as approximately 150 nm diameter.[11]

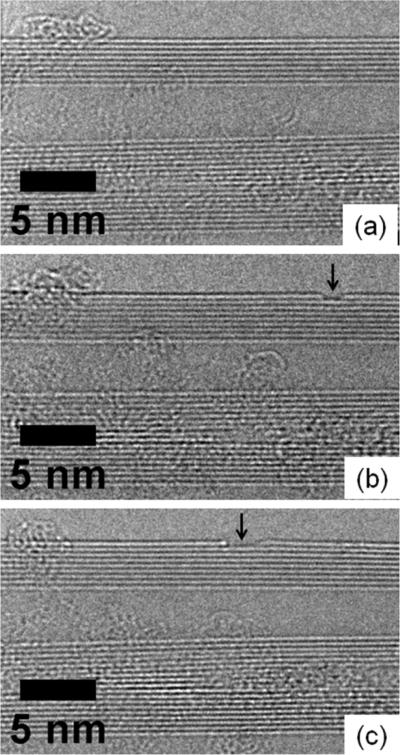

The environmental aspect of the microscope allows gas pressures up to about 20 mbar to circulate in the TEM specimen chamber while maintaining high resolution imaging conditions.[13-14] Our work so far has only utilized high purity singular gases such as hydrogen or oxygen, so as not to possibly degrade other microscope capabilities through contamination. Nevertheless this still permits very interesting experiments. For instance Koh et al [15] have studied the oxidation mechanism of carbon nanotubes under mild oxidation conditions (eg. 1.5 mbar O2 at 400 °C). The 80 kV imaging mode was also used to prevent knock-on damage to the nanotubes. They established that oxidation occurs by stripping away the nanotube outer wall, Figure 3, and not by attack of the nanotube cap, Figure 4, as had been previously postulated from ex situ observations. They also established a protocol for such work to eliminate any effects of the imaging electron beam.[15]

Fig. 3.

High resolution TEM images of the same multiwall carbon nanotube taken at (a) 400°C, (b) 400°C and (c) 520°C respectively. Images (b) and (c) were taken after the sample was oxidized in 1.5 mbar oxygen for 15 min with the beam blanked each time. The images show no nanotube damage upon heating alone and increasing sidewall oxidation upon heating in an oxygen environment. Arrows point to the same position on the nanotube, as shown by sequential micrographs.

Fig. 4.

High resolution TEM images of the same multiwall carbon nanotube (a) at 400°C and (b) oxidized at 1.5 mbar O2 at 400°C for 15 minutes with the beam blanked showing no damage at the cap of the nanotube even after oxidation at elevated temperature, contrary to previous suggestions not based on in situ experiments.[15]

The utility of electron tomography to provide three-dimensional information is well established. This approach is exemplified by its use to complement data from serial-sectioning scanning electron microscopy of varicella zoster virus nucleocapsids sequestered within nuclear cages formed by promyelocytic leukemia protepus.[16] The tomography revealed that the nucleocapsids were embedded and cross-linked by a filamentous electron-dense network within the cages. The tomography studies (e.g. Figure 5) were performed at 300 kV, as the high accelerating voltage permitted the study of thicker (300 nm) sections.

Figure 5.

TEM bright-field image of sequestered nucleocapsids in a vacuole of a melanoma cell which was analyzed using electron tomography, acquired on the Titan at 300kV at 0 degree tilt angle. Mature (C-type) and immature (B-type) capsids can be identified from this image.[16] 15 nm Au NPs were added and used as fiducial markers during the tomography acquisition and image alignment processes. Electron tomography allowed spatial resolution of the distribution of the nucleocapsids within the cell section.

Summary and conclusions

A characterization facility equipped with high performance modern instruments is indispensable for materials research and development in the nanotechnology era. A multiuser, institution-wide laboratory provides an efficient and cost-effective means to achieve this goal. We outline here our own process for establishing this capability, its philosophy in educating users and its business plan. An aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope is arguably the most advanced tool for such a facility, and examples of its utility are described.

Footnotes

It is a pleasure for us to acknowledge our colleagues within the Stanford Nanocharacterization Laboratory (SNL); Ann Marshall, Bob Jones, Arturas Vailionis, Chuck Hitzman, Mike Kelly and Droni Chui (and most recently Juliet Jamgaardt), who have worked alongside us in developing this facility under the initial guidance of Professor Arthur Bienenstock. Equipment funding has largely been provided by various divisions and faculty within Stanford University, with additional significant support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (ECCS- 0922684, DMR-1229290 and EAR-1125782). The SNL is an integral part of the Stanford Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence and Translation funded by NIH/NCI grant CCNE U54 U54CA151459 (S.S.G.) and the Center on Nanostructuring for Efficient Energy Conversion funded by DOE grant DE-SC0001060. The support of Professors Sam Gambhir and Shan Wang for the former and Professors Stacey Bent and Fritz Prinz for the latter is greatly appreciated. A high degree of confidence has been placed in the SNL by Stanford's Nano Committee, chaired by Professors Kam Moler and Philip Wong and overseen by various Deans; notably Ann Arvin (Research) and Jim Plummer (Engineering), and the University President, John Hennessy. Their encouragement has been pivotal throughout the whole process of establishing the SNL although the present authors are solely responsible for the ideas presented herein. Additional finances have also been generously provided by the Deans of Humanities & Sciences, Medicine and Earth Sciences, and many other faculty members.

Contributor Information

Robert Sinclair, Department of Materials Science and Engineering Durand Building Rm 113 496 Lomita Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-4034, USA.

Paul Joseph Kempen, Department of Materials Science and Engineering Durand Building 131 496 Lomita Mall Stanford University Stanford, Ca 94305-4034, USA.

Richard Chin, Stanford Nano Shared Facilities McCullough Rm 225 476 Lomita Mall Stanford, CA 94305-4045, USA.

Ai Leen Koh, Stanford Nano Shared Facilities McCullough Rm. 236 476 Lomita Mall Stanford CA, 94305-4045, USA.

References

- 1.Stanford University; 2013. http://snl.stanford.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinclair R, Aprahamian A, Bienenstock AI, Bradley JP, Clarke DR, Davenport JW, DiSalvo FJ, Evans CA, Jr., Lowe WP, Ross FM, Smith DJ, Soures JM, Spicer L, Tennant DM. Midsize Facilities: the Infrastructure for Materials Research. National Academies Press; Washington: 2006. National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kempen PJ, Hitzman C, Sasportas LS, Gambhir SS, Sinclair R. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 2013:1569. doi: 10.1557/opl.2013.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl JA, Koh AL, Dionne JA. Nature. 2012;483:421. doi: 10.1038/nature10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl JA, Garcia-Etxarri A, Koh AL, Dionne JA. Nano Lett. 2013;13:564. doi: 10.1021/nl304078v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung HJ, Dasgupta NP, Van Stockum PB, Koh AL, Sinclair R, Prinz FB. Nano Lett. 2013;13:716. doi: 10.1021/nl304400c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An J, Koh AL, Park JS, Sinclair R, Gur TM, Prinz FB. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:1156. doi: 10.1021/jz4002423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An J, Park JS, Koh AL, Lee HB, Jung HJ, Schoonman J, Sinclair R, Gür TM, Prinz FB. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2680. doi: 10.1038/srep02680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia CL, Lentzen M, Urban K. Science. 2003;299:870. doi: 10.1126/science.1079121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shim JH, Park JS, Holme T, Crabb K, Lee W, Kim YB, Tian X, Gür TM, Prinz FB. Acta Mater. 2012;60:1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDowell MT, Ryu I, Lee SW, Wang C, Nix WD, Cui Y. Adv. Mat. 2012;24:6034. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDowell MT, Kee SW, Harris JT, Korgel BA, Wang C, Nix WD, Cui Y. Nano Lett. 2013;13:758. doi: 10.1021/nl3044508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyes ED, Gai PL. Ultramicroscopy. 1997;67:219. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jinschek JR, Helveg S. Micron. 2012;43:1156. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh AL, Gidcumb E, Zhou O, Sinclair R. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2566. doi: 10.1021/nn305949h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichelt M, Joubert L, Perrino J, Koh AL, Phanwar I, Arvin AM. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002740. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]