Abstract

This article describes a program of prevention and intervention research conducted by the CHAMP (CHAMP – Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project; McKay & Paikoff, 2007) investigative team. CHAMP refers to a set of theory-driven, evidence-informed, collaboratively-designed, family-based approaches meant to address the prevention, health and mental health needs of poverty-impacted, African American and Latino urban youth who are either at risk for HIV exposure or who are perinatally-infected and at high risk for re-infection and possible transmission. CHAMP approaches are informed by theoretical frameworks that incorporate an understanding of the critical influences of multi-level contextual factors on youth risk taking and engagement in protective health behaviors. Highly influential theories include: the Triadic Theory of Influence (TTI) (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002), Social Action Theory (SAT) (Ewart, 1991) and Ecological Developmental Perspectives (Paikoff, Traube, & McKay, 2006). CHAMP program delivery strategies were developed via a highly collaborative process drawing upon community-based participatory research methods in order to enhance cultural and contextual sensitivity of program content and format. The development and preliminary outcomes associated with a family-based intervention for a new population, perinatally HIV-infected youth and their adult caregivers, referred to as CHAMP+, is described to illustrate the integration of theory, existing evidence and intensive input from consumers and healthcare providers.

Keywords: community-based, youth-focused, family-based HIV prevention and care

Introduction

Today, nearly 12 million young people globally are living with HIV, with adolescents/young adults accounting for more than 50% of new infections each year (Gopalan et al., in press). New York City is the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemics in the U.S. (NYCDOH, 2010). In fact, New York City has the highest number of people living with AIDS in the US, with more people infected than Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, and Washington, DC combined. HIV is also the health problem with the largest racial disparity: 80% of all new diagnoses are among African Americans and Latinos. The NYC epidemic is increasingly affecting young people of color, with disproportionate numbers of young adults being diagnosed with AIDS in their 20s, suggesting infection during adolescence (NYCDOH, 2010). Further, New York City has the largest cohort of perinatally HIV-infected youth, now approaching adolescence, in the U.S. (NYCDOH, 2010). These data underscore the urgent need to address the prevention of HIV infection and HIV care needs of youth.

Youth who enter adolescence under adverse circumstances (e.g. exposure to poverty, urban stressors, community violence, and racism along with diminished protective resources) are often ill-prepared to cope effectively with normative developmental challenges. For some youth, adolescence is thus associated with high rates of school dropout, early and risky sexual behavior, pregnancy, drug abuse, and serious behavioral difficulties (Annunziata et al., 2006; Beautrais, 2001; Kotchick, Armistead et al., 2006; Samuolis et al., 2005; Wild et al., 2004).

Low-income minority youth frequently evidence multiple, overlapping vulnerabilities and, thus, heightened risk for HIV exposure (Brown et al., 1997; Capaldi, Stoolmiller, Clark, & Owen, 2002; Houck, et al., 2006; Tubman et al., 2003). For example, African-American and Latino youth residing in urban, low-income communities have been found to be at 4 to 6 times greater risk for conduct difficulties in comparison to same-age peers (Angold & Costello, 2001; Tolan & Henry, 1996). Adolescents with elevated behavioral health needs also engage in unsafe sexual behavior and drug use due to impaired judgment, poor problem-solving ability, low self-esteem, self-destructive behaviors, and poor interpersonal relationships (Bauman & Germann, 2005; Brown et al., 1997; Capaldi et al., 2002; Houck, et al., 2006; Murphy, Mosciciki, Vermund, & Muenz 2000; Tubman et al., 2003; Walter et al., 1991; Cooper et al., 2003; Tice et al., 2001). Thus, it is imperative that youth struggling with overlapping health compromising and mental health issues receive theory-informed, evidence-based preventative interventions in order to interrupt risk-taking patterns as data suggest that HIV-related risk behavior that begin in adolescence persist into adulthood (Stiffman et al., 1992; Donenberg & Pao, 2005).

Perinatally HIV-infected (pHIV+) adolescents are a fast emerging risk group for mental health and behavioral difficulties which can serve to jeopardize their own health and that of others (Elkington, in press; Gretchen, 2009; Havens & Mellins, 2008; Mellins et al., 2008; Mellins et al., 2009). With the advent of antiretroviral treatment (ART), pHIV+ youth, once not expected to outlive childhood are reaching adolescence and young adulthood in relatively large numbers. At the start of 2009, an estimated 7,757 pHIV+ youth were living with HIV in the United States (US; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Over 25% of these youth live in New York City (NYC) and 79% were 13 years and older (NYCDOH, 2010). Thus, pediatric HIV is now an adolescent epidemic in the US and other countries with long standing access to ART.

With the prospect of a longer lifespan, pHIV+ youth must negotiate normative developmental issues, such as puberty, growth, peer relations and sexuality while simultaneously coping with a stigmatizing disease (Donenberg and Pao, 2003; 2005; Havens and Mellins, 2008). Further, perinatally infected adolescents must incorporate frequent visits to health care providers and complex medication schedules into their daily lives (Gretchen, 2009), while simultaneously experiencing normative social pressures to “fit in.” In addition, they face challenges, such as being reared by a HIV+ parent or losing parents and/or other family members to AIDS (Griffith, Azuma, Chasnoff, 1994; Havens and Mellins, 2008).

Further complicating the life circumstances of pHIV+ youth is the fact that even brief episodes of non-adherence to ART medications can permanently undermine treatment and lead to increased resistance to medications (Patterson et al., 2000; Mellins, Brakis-Cott, Dolezal, & Abrams, 2004; Raisner et al., 2009). Across chronic health conditions, non-adherence to medications increases substantively during adolescence, and HIV has been no exception. Several studies of older children and adolescents have shown rates of non-adherence to range from 18–50% (Haberer & Mellins, 2009; Williams et al., 2006; Mellins et al., 2009; Marhefka et al., 2004; Marhefka et al., 2008; Marhefka, Tepper, Brown, & Farley, 2006), with an appreciable proportion presenting with detectable viral load (Haberer & Mellins, 2009), and thus, a high percentage of perinatally infected adolescents may be living with a multidrug resistant virus.

This grim reality becomes a serious public health issue as youth approach adolescence, a time of increased experimentation with sexual behavior and drug use. For HIV+ youth, engaging in any type of risk behavior increases opportunities for transmission of HIV (including ART-resistant strains of the virus) to others. The fact that perinatally infected children are now becoming adolescents in relatively large numbers presents a public health concern that warrants immediate attention, particularly in New York City (NYC). In fact, there is increasing evidence that they are vulnerable to poor behavioural health outcomes. These include serious mental health needs (Mellins et al., 2009; Chernoff, Gadow, Woods, 2009) and sexual and drug risk behaviours, e.g., teen age pregnancies, unprotected sex, and, for a small subset-early initiation of sex (before age 15). All have been associated in prior studies with multiple partners and lack of condom use (Bauermeister, Elkington, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Mellins, 2009; Elkington, Bauermeister, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal , & Mellins, 2009; Mellins et al., 2009). Unfortunately, few, if any theory-driven, evidence-informed programs have focused on the prevention of overlapping risk behaviors, particularly in populations of high risk, while simultaneously being capable of impacting serious health and/or behavioural health needs.

The CHAMP (Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project) Approach

CHAMP refers to a set of theory-driven, evidence-informed, collaboratively-designed, family-based approaches meant to address the prevention, health and mental health needs of poverty-impacted, African American and Latino urban youth who are at risk for HIV exposure or perinatally-infected and at high risk for re-infection and possible transmission. CHAMP approaches are informed by theoretical frameworks that incorporate an understanding of the critical influences of multi-level contextual factors on youth risk taking and engagement in protective health behaviors. Highly influential theories include: the Triadic Theory of Influence (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002), Social Action Theory (Ewart,1991) and Ecological Developmental Perspectives (Paikoff, Traube, & McKay, 2006). In addition, CHAMP program delivery strategies were developed via a highly collaborative process drawing upon community-based participatory research methods in order to enhance cultural and contextual sensitivity of program content and format (McKay, Hibbert et al., 2006; 2007). The systematic adaptation of CHAMP core components to new populations and contexts is illustrated by a discussion of the development and outcomes associated with CHAMP+, a family-based intervention targeting the overlapping health and mental health outcomes for perinatally HIV-infected youth (McKay et al., 2006).

Originally, the CHAMP Family Program was created to promote resilience in uninfected inner-city youth and their families at pre- and early adolescence (prior to the onset of sexual activity) (Madison et al., 2000; McKay et al., 2000). CHAMP bolsters key family and youth processes related to youth risk taking behaviors by providing opportunities for youth and their parents (including biological parents, grandparents, relatives or foster parents) to strengthen communication skills, particularly around sensitive topics such as puberty, sexuality and HIV. CHAMP also improves family decision-making skills with parents providing leadership in aspects of family life that offer youth protection, such as supervision and monitoring of peer relations. Increasing youth social problem-solving skills are also important targets for CHAMP.

The CHAMP Family Program approach has been adapted and tested for use with vulnerable, youth and families across a variety of contexts and cultures, including the urban inner cities of Chicago and New York in the US, as well as internationally in Argentina and South Africa (Bell, et. al., 2006). For each site in which CHAMP is implemented, consumers are actively involved in designing, implementing, and providing feedback on all aspects of the CHAMP adaptation and implementation, increasing the intervention’s cultural and contextual sensitivity and applicability (for example see Bell et al., 2006; Baptiste et al., 2006; McKay & Paikoff, 2007; Petersen, Mason, & Bhana, 2006 for a description of the collaborative process of adaptation and development of CHAMP across contexts). Data from multiple studies of CHAMP across contexts and cultures reveal significant associations with enhancements in family-level protective processes (family decision making; HIV knowledge; communication comfort), caregiver monitoring and supervision, and youth reports of significantly reduced time spent in sexual possibility situations (see McKay et al., 2000; McKay et al., 2004; Mckay & Paikoff, 2007 for summaries of findings; Bell et al., 2009; Baptiste et al., 2006).

Core components of the original CHAMP Family Program

Originally, the first CHAMP Family Program was informed by an ecological developmental perspective (Paikoff, Traube & McKay, 2006). More specifically, this theoretical perspective understands adolescent sexual decision making as influenced by a combination of youth cognitive factors and behavioral skills, as well as contextual factors, particularly family and friendship relationships (DiClemente, Hansen, & Ponton, Eds., 1996; Walter, Vaughan, and Cohall, 1991; Walter, Vaughan, and Cohall, 1993a; Walter, Vaughan, Ragin, and Cohall, 1994; Walter, Vaughan, Gladis, and Ragin, 1993b; Shafer and Boyer, 1991).

During the 1990s when the original CHAMP Family Program was developed, the emphasis on the importance of family relationships and peer relational factors in relation to understanding high-risk sexual behaviors in adolescents and ultimately guiding HIV prevention efforts was an important advance (Black, Ricardo, and Stanton, 1997; Romer, 1994; Biglan et al. 1990; Katchadourian, 1990). For example, at that time, emerging findings revealed the importance of family availability and monitoring as protective factors for high-risk sexual behavior. Findings have also pointed to areas of family interaction associated with the sexual risk experience of youth. For example, sexually active African American adolescents report more conflict with parents and a lack of communication (Black, Ricardo, and Stanton, 1997; Katchadourian, 1990). For Latino families, due to generally conservative attitudes towards sexuality, Latino parents may be less likely to provide information on sexuality to their children (Marin and Gomez, 1997). In particular, Latino adolescents report less sexual information from their parents and are less likely to receive information about AIDS than non-Latino white adolescents (Baumeister, Flores, and Marin, 1995). Family structure may also affect HIV risk, with adolescents living in single mother families becoming sexually active at an earlier age than adolescents from mother/father or mother/other adult families (Flewelling and Bauman, 1990; Inazu and Fox, 1980).

Minority families living in poor neighborhoods often utilize creative strategies for enhancing positive outcomes for their youth (Jarrett, 1995). These strategies serve to limit influences of the neighborhood outside of the family and avoid neighborhood dangers, thereby setting up conventional developmental trajectories (i.e., delaying pregnancy and parenting, and completing high school). Parents provide opportunities for their youth through their own supportive adult networks, particularly family members who help to monitor youth, and make connections to other resources (e.g., churches and schools).

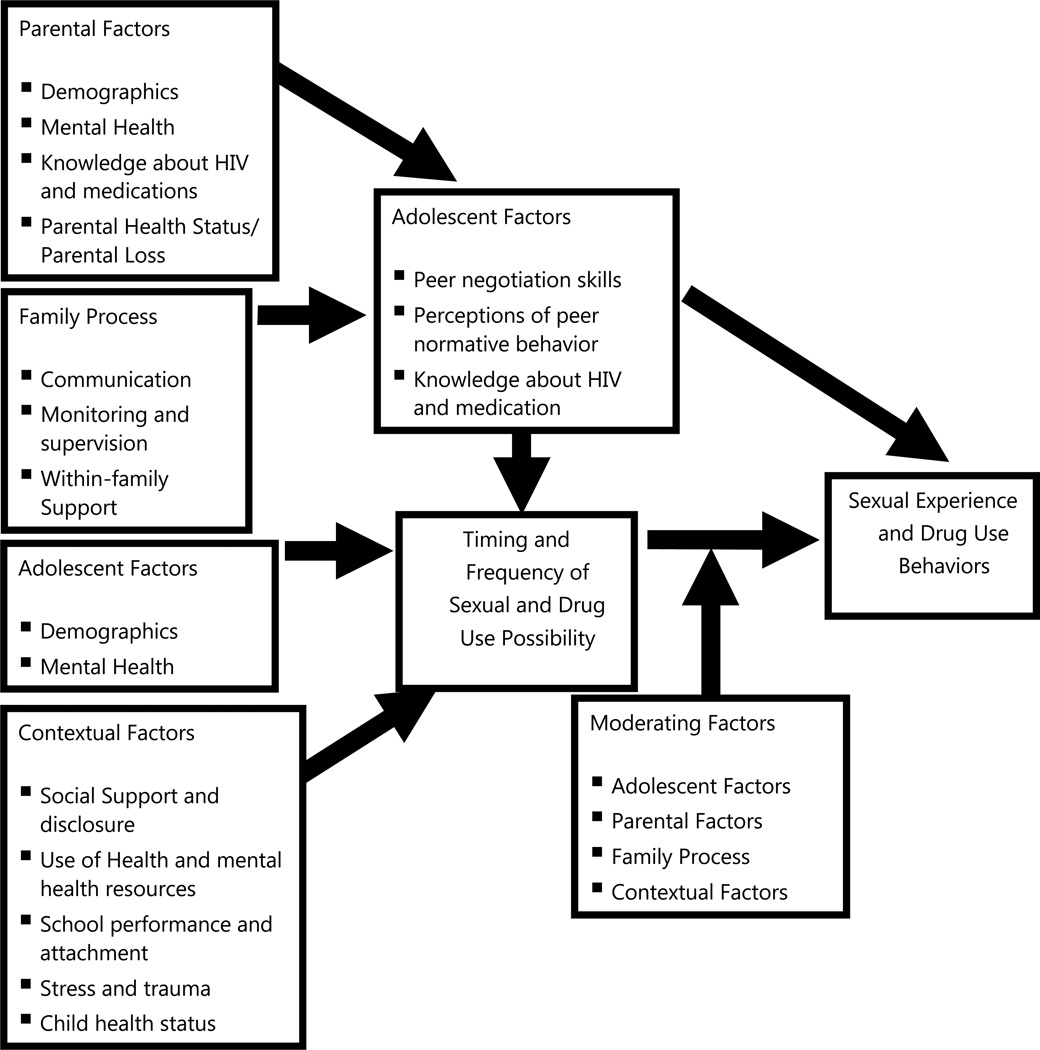

Peer relations, particularly, friendships, also are relevant to the understanding of sexual risk behavior for youth (Brown, Dolcini, and Leventhal, 1997; McBride, Paikoff, and Holmbeck, 1999). Research with minority and majority youth has indicated that peers are a strong influence on the rate of sexual activity and condom use (Black et al. 1997; Romer et al. 1994). Friendships with peers who are not involved in problem behaviors are also protective factors for high risk sexual behavior (Biglan et al. 1990). Based upon this body of research, a theoretical model guiding the development of the CHAMP Family Program was created (see Figure 1 as well as Paikoff, 1997 for summary).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model organizing developmental and ecological influences on youth HIV risk behaviors

More specifically, the CHAMP Family Program targets key family processes (e.g. family communication, supervision/monitoring, within family support), along with building parental resources (e.g. social support, use of health and mental health resources) and HIV/AIDS knowledge. In addition, children’s peer negotiation skills, as well as HIV/AIDS knowledge are supported by the intervention in order to reduce opportunities for initiation of sexual experience and reduce risk for HIV infection or transmission.

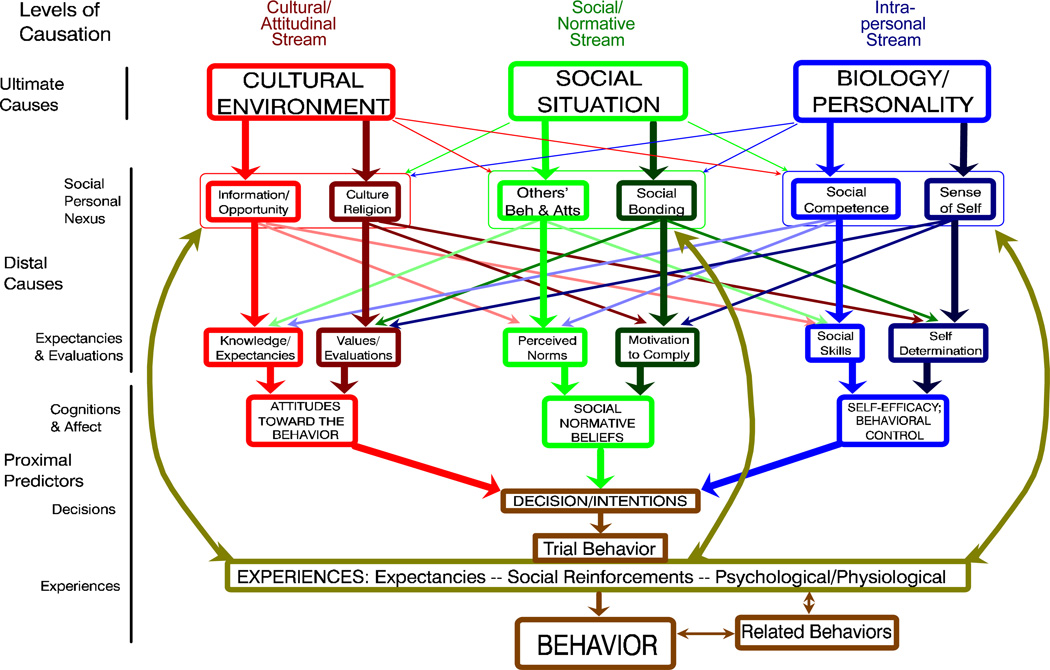

As the epidemic entered its second decade, the CHAMP investigative team was tasked with developing and testing a CHAMP Program for South African (CHAMPSA) youth and their families in the midst of rates of HIV infection not seen in the US. Significant cultural and contextual adaptations were needed, as well as new theoretical frameworks, which could inform the next iterations of CHAMP models (Bell et al., 2006). Thus, we drew upon the Triadic Theory of Influence (TTI; Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002). TTI was used to guide the cultural and contextual adaptation process of CHAMP to the South African context (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002). More specifically, in order to be sufficiently flexible to cross boundaries and contexts, CHAMP began to be informed by a more comprehensive ecological approach and began to understand risk behavior as being a product of multiple streams of influence - an intra-personal stream linked to biology/personality, a social normative stream linked to the social/inter-personal situation, and a cultural attitudinal stream linked to the socio-cultural environment (Flay and Petraitis, 1994).

TTI includes a focus on three streams of influence. The streams include: 1) cultural-environmental influences on knowledge and values; 2) social situation contextual influences on social bonding and social learning; and 3) interpersonal influences on self-determination/control and social skills (see Figure 2; Chunn, 2002; Flay, Snyder, and Petraitis, 2009).

Figure 2.

Theory of Triadic Influence

CHAMPSA targeted these three streams of influence via a set of seven field principles thought to be necessary for any successfully intervening as a universal health behavior intervention (Bell, Flay, Paikoff, 2002). The seven fields include: 1) re-building the village - consisting of developing and expanding community partnerships and coalitions through a level of community organization around health behavior issues (derived from the “cultural/attitudinal stream” and “social/normative stream” of TTI), 2) providing access to health care - addresses highly influential, individual-level risk factors that require a community-level service (derived form the ”biology” in the Intra-personal stream of TTI), 3) improving bonding, attachment, and connectedness dynamics - within the community and between stakeholders (derived from the “social bonding” in the social/normative stream of TTI), 4) improving self-esteem and self-respect (“sense of self” in the intra-personal stream of TTI), 5) increasing social skills of target recipients (“social skills” in the intra-personal stream of TTI), 6) reestablishing the adult protective shield and monitoring problem behaviors (“others’ behavior and attitudes” in the social/normative stream of TTI), and 7) minimizing the residual effects of trauma (“behavioral control - self-management skills and affect regulation” in the intra-personal stream of TTI).

These seven field principles guided the CHAMPSA academic/community partnership to actualize the Theory of Triadic Influence and to base their intervention on sound scientific theory (Bell, et al. 2002). For example, in regards to re-building the village, the entire development and testing of the CHAMPSA Family Program was overseen by a Community Collaborative Board, consisting of key service, governmental, advocacy and family stakeholders. This body provided ongoing intensive input that helped to set the family-based approach within the needs of the South African context. Units on coping with loss and death as a result of AIDS were added to program content to incorporate the devastations of the epidemic in communities across South Africa (See Petersen et al., 2008 for additional details).

Adapting CHAMP Model to New Populations

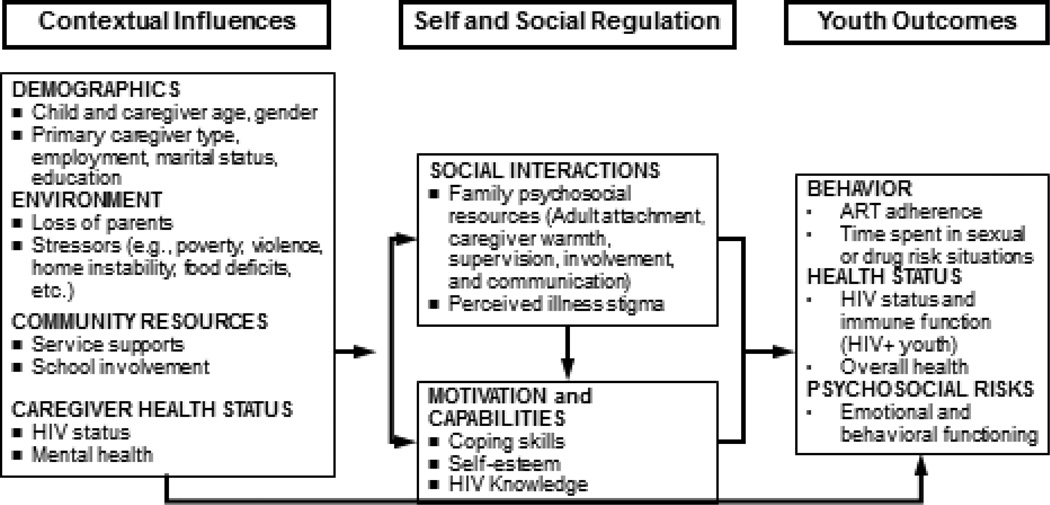

In addition to international adaptations, as the epidemic began to enter its third decade, new populations affected by HIV began to emerge in the US. As CHAMP began to tackle HIV prevention for perinatally infected HIV+ youth and their adult caregivers, we turned to Social Action Theory (SAT) because the newest iteration of CHAMP, referred to as CHAMP+, needed to address more serious presenting mental health and behavioral health needs of pHIV+ youth, as well as their HIV prevention needs simultaneously. In the case of CHAMP+, Social Action Theory was helpful in organizing findings from a number of more recent studies which found that family, social, and contextual factors were strongly associated mental health, medication adherence, and sexual and substance use behaviors among HIV+ youth (Traube et al, 2011; Mellins et al., 2008). Social Action Theory (SAT; Ewart, 1991) is a model of behavior change that emphasizes the context in which behavior occurs, and developmentally driven self-regulatory and social interaction processes that affect adaptive behavior. SAT was critical to informing the design of CHAMP+ in which we posited that youth outcomes are influenced by a) context (e.g., stressors and resources); b) self-regulation (motivation and capabilities) and c) social regulation (e.g., family resources, relationships, stigma) (See Figure 3). More specifically, in order for the CHAMP+ Family Program to target an expanded number of outcomes related to behavior (e.g. medication adherence, time spent in sexual or drug risk situations), health (e.g. HIV status and immune function) and psychosocial risks (e.g. emotional and behavioral functioning), programmatic components needed to take into account unique social processes related to HIV (e.g. family processes similar to the original CHAMP plus illness stigma), as well as youth knowledge and skill.

Figure 3.

Modified Social Action Theory

With funding from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Health, the goal of CHAMP+ was to: (1) adapt the CHAMP model to address both prevention and treatment needs of pHIV+ youth and their families; (2) evaluate the feasibility of implementing such a model in medical settings where youth and families receive their health care; and (3) examine short-term preliminary youth and family outcomes associated with participation in the CHAMP+ Family Program. The description of this pilot study next is meant to illustrate how existing evidence-based programmatic components, guided by Social Action Theory, were integrated with intensive stakeholder input to create a potentially effective, contextually, culturally tailored intervention.

Phase 1: CHAMP+ Family Program Collaborative Adaptation and Development Process

The first step towards the creation of the CHAMP+ Family Program was the organization of a collaborative planning team from two HIV primary and tertiary care clinics in major NYC medical centers, consisting of pediatric HIV primary care staff and pHIV+ youth and their adult caregivers. This team was convened to review the existing CHAMP program materials, as well as existing evidence for its delivery and associated outcomes. In addition, findings related to the needs of pHIV+ youth and their families were also reviewed, as well as key stakeholder input on need, specific factors that could potentially impact implementation and outcomes with a new population in new settings.

Phase 1 Methods

In order to reach consensus about intervention goals and curriculum development, we drew on community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods to refine and adapt the CHAMP family intervention for use with pHIV+ youth and families. Initially, three pHIV+ youth and five caregivers of pHIV+ youth met with research staff in one of the two clinics over a period of 6 months to: (1) identify salient issues related to youth HIV, family life, and youth development and risk; (2) review and provide feedback on existing CHAMP materials; and (3) discuss feasibility concerns. Findings from this preliminary collaborative work supported the use of original CHAMP materials, as well as highlighted the need for an intervention that could address the unique circumstances and needs of pHIV+ youth and their caregivers. Furthermore, the findings aided medical providers in their work with youth and families around health-related issues.

Next, we expanded our work to the second pediatric clinic by examining similarities and differences and expanding recommendations for the second clinic. The research team worked closely with medical staff to identify a second group of families rearing pHIV+ youth. At the second site, youth who were slightly older than those in the first collaborative working group (>14 years) were recruited for their feedback in order to obtain perspectives on issues that can be anticipated as youth enter mid/late adolescence.

This second collaborative working group met for eight two-hour sessions over a period of three months to: (1) expand on salient issues related to HIV, family life, and youth development and risk that were previously identified; (2) re-review existing CHAMP materials to assess appropriateness of content and format from new perspectives; (3) develop new, relevant intervention content based upon perceived needs and the first set of recommendations; (4) identify potential challenges to youth and adult caregiver participation; and (5) discuss feasibility issues and implementation strategies. Clinic staff at both sites then met with research staff for a final examination of proposed intervention content, and plan for implementation and examination of CHAMP+ at each of the two sites.

Phase 1 Results

Key changes were made to the original CHAMP theoretical model in order to adequately address the unique needs of pHIV+ youth and their families, as well as to inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of the CHAMP+ Family Program. More specifically, issues related to HIV illness and medication knowledge, stigma associated with HIV, social support and decision making related to disclosure of serostatus were added to the model (mapping onto the self and social Regulation processes outlined in Social Action Theory. Further, family level issues (e.g. death of a parent, HIV status of parent, family HIV disclosure) were also included (noted as contextual influences according to Social Action Theory). Additional changes included the recognition of the importance of the child’s health status and their use of health and mental health services (Social Action Theory contextual influences). Finally, CHAMP+ focuses on peer negotiation skills and perception of peer normative behavior in the context of pediatric HIV (part of the self and social regulation domains of Social Action Theory). The intent is to bolster youth ability to confront sexual pressure and to address issues related to “feeling different” from peers. These are foundational skills for pHIV+ youth that will better equip them to make thoughtful decisions related to dating and relationships within the context of having a highly stigmatizing and sexual transmittable illness.

Based on the Phase 1 work, the CHAMP+ Family Program curriculum focused on the following topics: (1) The impact of HIV on the family; (2) Loss and stigma associated with HIV disease; (3) HIV, health, and antiretroviral medication protocols; (4) Family communication about puberty, sexuality and HIV; (5) Parental supervision and monitoring related to sexual possibility situations and sexual risk taking behavior; (6) Helping youth manage their health and medication; and (7) Social support and decision making related to disclosure of HIV status.

Similar to the original CHAMP Family Program, the intervention is delivered across 10 two-hour sessions via a multiple family group format. The groups included approximately 6 to 10 families (n= 12–20 participants per group), target youth and adult caregivers, per group. Also, similar to the original CHAMP Family Program, a combination of multiple family group practice activities and discussions and separate parent and child group meetings are included in each intervention session.

Phase 2: Pilot Testing of the CHAMP+ Family Program

Given the adaptation of the CHAMP curriculum to a new setting (pediatric HIV clinics) and the additional sessions added to the curriculum that addressed living with HIV, a small pilot trial was conducted to examine feasibility, acceptability and preliminary impacts on youth and family outcomes.

Phase 2 Methods

Participants

Participants for the pilot trial of CHAMP+ were selected from the two clinics who participated in the adaptation phase. Both sites were located in major medical centers in New York City. Both pediatric HIV care sites focused on the provision of comprehensive primary and tertiary care to families affected by HIV. In order to be eligible for participation in the pilot test, youth were pHIV+, between the ages of 10–14 years, and were aware of their diagnosis (HIV status disclosed to the youth prior to the beginning of the intervention). Caregivers had to be the child’s legal guardian and have the capacity to sign legal consent for the child’s participation (foster care parents cannot provide legal consent for participation in psychosocial research studies in New York City).

A list of eligible families at each site was compiled by clinic staff. Adult caregivers on this list were approached by the child’s primary care provider during the child’s monthly medical appointment. The opportunity to be included in the pilot examination of the CHAMP+ was presented, including procedures for assuring confidentiality. After a thorough discussion, verbal consent to be contacted by the research staff was requested. Research staff then reached out to the adult caregivers to schedule a time to meet and review written consent forms with caregivers first. Child assent was also obtained from all participating children.

Sample

Nineteen caregiver/youth family dyads (n=38) across two pediatric HIV clinics were successfully recruited into the pilot examination. Seventeen families (n=34) completed the pilot intervention and participated in post-intervention. The mean age for caregivers was 55 years. Eighty three percent of adult caregivers were female and 89% of adult caregivers identified as Black. Caregivers included birth parents, relatives, and adoptive parents. The mean age of participating children was 13 years, 72% of participants were male and all children belonged to the same racial/ethnic group as their caregivers.

Procedures

The intervention pilot consisted of ten sessions led by trained facilitators. IRB approval was obtained for this study. Each CHAMP+ session began with a group dinner to increase comfort, group cohesiveness, and attendance. Child care and transportation costs were also defrayed.

Measures

Standardized instruments from previous studies involving large samples of urban inner-city youth and families, including the CHAMP Family Program study, as well as studies with pHIV+ youth, were selected based on the CHAMP+ theoretical model. Assessments were administered at baseline, posttest (10 weeks) and at 3-month follow-up (approximately 24 weeks following baseline). Assessments were administered to all children in small, break-out groups as well as individually depending on the nature of the assessment (i.e. interviews about sexual possibility situations were administered privately with each individual child), and caregiver assessments were administered in a small group settings.

Demographics and descriptive data

Descriptive data about caregiver and child gender, race/ethnicity and age, caregiver relationship to child, child disclosure status, reports of HIV disclosure to others, and child drug and alcohol use, sexual possibility situations, and sexual intercourse were collected in order to provide descriptive information on pHIV+ pre and early-adolescent youth.

Intervention session attendance

Attendance was also recorded for all family members for all sessions of all groups at both participating clinics.

Youth behavioral and knowledge outcomes

Child mental health

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief measure of child mental health and functioning that has been shown to have reasonable reliability and validity for 5 to 15 year olds (Goodman, 2001). The parent report version used in CHAMP+ comprises five subscales measuring pro-social behavior, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and conduct problems as well as a total difficulties score and an impact scale that measures the degree of functional impairment. Subscales contain 5 items each such as “my child is considerate of other people’s feelings” or “my child often has temper tantrums” with a response set of 0=not true, 1=somewhat true, and 2=certainly true. The parental SDQ has a mean internal consistency of .73 when measured with Cronbach’s alpha (Goodman, 2001).

HIV treatment knowledge

Knowledge about ARV treatment for HIV+ individuals was assessed using a 6-item measure created for this study. Knowledge items relevant to HIV treatment for pHIV+ youth (i.e., “viral load test measure how much HIV is in the blood”; “If we say the virus is “resistant” to a particular medicine that means the medicine no longer works to slow down the virus”) were created based on information collected from meetings with clinicians at each participating clinic as well as from consultancy meetings with phase one families. Each item had a response set of 1 = True; 2= Not True; 3 = Unsure. Items were collapsed, such that correct responses were given a score of 1 and incorrect or unsure answers were given a score of 0. Items were then summed in order to obtain a total score, with higher scores reflecting more correct knowledge about HIV transmission.

Family processes

Supervision and monitoring

A 46-item interview adapted from the Pittsburgh Youth Study (Loeber et al. 1986) and the Chicago Youth Development Study (Tolan et al. in press) was used to assess monitoring and supervision. Both children and parents responded to this measure, based on items from the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986) and the Family Assessment Measure (FAM; Skinner et al. 1983). Items are broken down into six scales: 1) discipline effectiveness; 2) positive parenting; 3) child rules; 4) extent of involvement/supervision; 5) amount of time together; and 6) child-based difficulties. Inter-item reliabilities of the subscales in a sample of 500 urban parents of pre and young adolescent males ranged from .68 (rules) to .81 (extent of involvement/supervision). Additional items adapted from the Oregon Youth Study (Jordan, 1995) address details about monitoring; e.g., how parents keep track of children’s whereabouts, who they are with, household rules, and how often children are left in charge of the home and the other children.

Parental involvement in child medication adherence

Caregivers and children answered two parallel questions to assess family involvement in medication adherence. For caregivers questions included, “How dependent on you is your child to take medication properly?” and “How likely is it that you would know if child missed medication?” For children questions, “How dependent are you on your parent to take medication properly?” and “How likely is it that your parent would know if you missed medication?” Each item had a response set ranging from 1=totally dependent on parent to 4=mostly responsible.

Phase 2 Results

Descriptive baseline data

First, descriptive analyses were conducted, which highlighted some areas of specific concern for participants at baseline prior to beginning the intervention pilot test. For example, 34% of youth reported feeling guilty about having HIV, and 17% reported thinking less of themselves because they had HIV. Disclosure of HIV status was also a concern for youth. Seventy-eight percent of youth reported often keeping their HIV status a secret from others, and 50% reported that none of their friends knew they had HIV. In contrast, substance use was not yet a concern for these youth. No youth reported ever using marijuana, drinking alcohol, or smoking cigarettes in the past month. There was also only one report of sexual intercourse among these youth, although 44% had experienced situations of sexual possibility (i.e. kissing, touching, being along without adult supervision).

Data analysis

Next, we conducted paired sample t-tests to compare scale means for the group of children and caregivers who received the intervention from baseline to posttest. Although there were 17 child/parent dyads who participated in the intervention, one family was missing child post-test interview data (due to a hospitalizing), and one family was missing both caregiver and child post-test interview data (due to a family move).

Youth outcomes

Table 1 presents caregivers’ reported improvement in their child’s mental health and functioning from baseline to 3-month follow-up post assessment. Caregivers also reported a decrease in their children’s emotional symptoms (t(13)=3.1, p <.01), conduct problems (t(13)=2.2, p<.05), and functional impairment (t(13)=2.9, p<>01). Although mean scores also showed improvement in pro-social behavior, problems with peers, and hyperactivity, these changes were not statistically significant. Table 1 also presents mean changes in children’s treatment knowledge from baseline pre-intervention to 3-month follow-up post-intervention. Children’s treatment knowledge is marginally significant (t(12)=1.9, p < .10), and reflects, on average, a one point increase in child treatment knowledge from baseline to follow-up.

Table 1.

Youth Behavioral and Knowledge Outcomes

| Variable | Pre-test Mean (SD) |

Post-test Mean (SD) |

t | DF | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-Social Behavior | 7.3 (2.3) | 7.5 (1.9) | −0.7 | 14 | ns |

| Emotional Symptoms | 3.5 (2.7) | 2.3 (2.2) | 3.1 | 13 | p<.001* |

| Conduct Problems | 2.9 (2.5) | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.2 | 13 | p<.05* |

| Peer Problems | 2.0 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.5) | −0.6 | 14 | ns |

| Hyperactivity | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.0) | 0.9 | 11 | ns |

| Functional Impairment | 12.6 (4.8) | 10.6 (3.7) | 2.9 | 13 | p<.01* |

| Treatment Knowledge | 2.7 (1.5) | 3.7 (2.0) | 2.0 | 11 | <0.10 |

Family process outcomes

Table 2 presents mean changes in caregiver monitoring and supervision of children reported by both parents and children. Perhaps reflecting more opportunity for practice with, and thus more confidence about, supervising their children, caregivers reported an increase in the effectiveness and comfort they had with disciplining their children (t(13)=-4.0, p <.01) and a reduced level of supervision and monitoring (t(12)=2.3, p = .039). Children were not asked about discipline, but also reported a reduced level of parental monitoring following the intervention (t(11)=4.3, p=< .001). Table 2 also presents data on caregiver involvement in child medication adherence. From pre-intervention baseline to 3-month follow-up post-intervention, both caregivers (t(8)=1.9, p < .10) and youth (t(11)=2.0, p < .10) reported marginally significant increases in how likely it would be for caregivers to know if their child missed a medication dose; however, only children reported marginally significant increases (t(12)=2.0, p < .10) in how dependent they were on their caregivers to take medication properly.

Table 2.

Family Process Outcomes: Supervision and Monitoring and Parental Involvement in Medication Adherence

| Variable | Pre-test Mean (SD) |

Post-test Mean (SD) |

t | DF | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervision and Monitoring (Parent Report) | 51.7 (4.4) | 49.3 (5.2) | 2.3 | 12 | p <0.05* |

| Child Discipline (Parent Report) | 7.1 (2.3) | 10.1 (0.9) | 4.0 | 13 | p <0.01* |

| Supervision and Monitoring (Child Report) | 46.8 (6.0) | 44.1 (5.2) | 4.3 | 11 | p <0.01* |

| Parent would know if child missed medication (Parent Report)* | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.9 | 8 | p<0.10 |

| Child dependence on caregiver to take medication properly (Child Report)* | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.0 | 12 | p<0.10 |

| Parent would know if child missed medication (Child Report)* | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.0 | 11 | p<0.10 |

Attendance at sessions for all groups across the two participating clinic sites was extremely high. On average, 100% of families (n=34) attended greater than half of all sessions, indicating that both caregivers and children were engaged in the intervention over a 3-month period of time. Thus, in this pilot study CHAMP+ showed promise in being able to engage youth and their families and impact multi-level outcomes for highly vulnerable children and families.

In sum, in order for interventions to be adapted to new populations, contextually specific programs need to be tailored to the particular needs of that population; achieved primarily through collaboration with the community and tailoring of theoretical models to the unique population and its circumstances.

Discussion

This paper focuses on the evolution of a program of research that attempts to integrate theory with existing evidence and intensive input from stakeholders in order to create and test culturally and contextually relevant approaches to HIV prevention and care for youth of color. Initial efforts of the CHAMP investigators were guided by emerging evidence that youth-focused HIV prevention efforts need to address the significant influence of family and peer relationships on sexual risk taking. An ecologically focused, developmental perspective was needed to expand the focus of the CHAMP Family Program to important proximal youth, family and peer perceptual targets.

However, as CHAMP moved towards addressing the needs of youth within the South African epidemic, the need to expand the focus to both context (e.g. loss and death), culture (e.g. HIV myths, stigma and barriers to communication), as well as family and peer influences required more comprehensive theoretical perspectives. The introduction of the Triadic Theory of Influence helped to focus the CHAMPSA Family Program on these critical influences not found within the U.S. context.

Further, as CHAMP was adapted for new populations with serious physical and mental health challenges, models that focused on self and social regulation processes, as well as specific illness contextual factors were needed. Social Action Theory provided such a guide for organizing and expanding programmatic components.

However, existing evidence-informed components and theories were deemed insufficient to creating new approaches to HIV prevention and care. The CHAMP approach also relies upon intensive collaboration among researchers, an expanded range of stakeholders and consumers. In the case of CHAMP+, intensive input from clinic staff, and consumers was sought to adapt an evidence-based HIV intervention for a new population of HIV+ youth. The CHAMP+ collaboration was included here to illustrate the important role consumer partners can play in the development of theory-informed, culturally and contextually tailored intervention programs for HIV+ youth and families. CHAMP+ focused on pHIV+ youth and the unique developmental challenges with their transition into adulthood. These adolescents are largely comprised of ethnic minorities residing in poor urban neighborhoods that are particularly vulnerable to high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, mental health problems, and non-adherence to medical treatment due to environmental and familial risk factors. These risk behaviors compromise the health and well-being of pHIV+ adolescents, and also pose a significant public health concern for increased resistance to medications and increased HIV transmission to partners and children.

Although preliminary, findings reveal an association between the CHAMP+ intervention and caregivers reports in youth emotional difficulties, conduct problems, and functional impairment, as well an increase in treatment knowledge from baseline to follow up. Caregivers also reported improved comfort in effectively disciplining their children resulting in a significant decrease in child supervision and monitoring. However, these preliminary findings need to be interpreted cautiously as the study has a number of limitations. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the outcomes, but does present an opportunity for further research. The small number of participants may not reflect all of the relationships and interactions of other covariates, thereby introducing the possibility of biased estimates and significance tests. There is potential measurement error due to self-report bias on emotional and family process indices. However, as this is a pilot study, it does provide valuable information to the CHAMP investigators to continue to pursue this line of inquiry.

Adolescents continually face challenges related to engagement in risk taking behaviors (e.g. sex, drug use). Within the context of HIV, these risks can increase negative consequences for these young people. Their limited access to healthcare and low ART adherence can be bolstered by programs similar to CHAMP+. The further development of theory-driven, evidence-based interventions that are able to incorporate cultural and contextual influences, as well as recognize familial and individual factors that can serve to reduce youth risk are critically needed. The CHAMP approach with CHAMP+ as an example, can provide important guidance in terms of options for integrating theory, evidence and collaborative input to contribute to relevant HIV prevention and care models for youth.

Acknowledgements

The contribution of key collaborators is gratefully acknowledged (Paikoff, Bell, Baptiste, Gibbons, Bhana, Petersen, Abrams), as well as the financial support of the National Institute of Mental Health (NR 010474 (PI: Mellins); R01 MH 64872 (PI: McKay); R01 MH5571 (PI: Paikoff); R01 MH 63622 (PI: McKay); R34 MH072382 (PI: McKay).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mary McKernan McKay, McSilver Professor of Poverty Studies, Silver School of Social Work, New York University, Director, McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy & Research.

Stacey Alicea, Doctoral Candidate, New York University.

Laura Elwyn, Research Analyst, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry.

Zachary R.B. McClain, Research Fellow, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry.

Gary Parker, Deputy Director, NYU McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy & Research.

Latoya A Small, Doctoral Student, Silver School of Social Work, New York University.

Claude Ann Mellins, Research Scientist & Professor, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies.

References

- Angold A, Costello E. The epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. In: Goodyer I, editor. The depressed child and adolescent: Developmental and clinical perspectives. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 143–178. [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata D, Hogue A, Faw L, Liddle HA. Family functioning and school success in at-risk, inner-city adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 2006;35(1):100–108. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste DR, Bhana A, Petersen I, McKay M, Voisin D, Bell C, Martinez DD. Community collaborative youth-focused HIV/AIDS prevention in South Africa and Trinidad: Preliminary findings. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(9):905–916. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Elkington K, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Sexual behavior and perceived peer norms: Comparing perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-affected youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1110–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9315-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Berman R. Adolescent relationships and condom use: trust, love and commitment. AIDS Behavior. 2005;9(2):211–222. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister LM, Flores E, Marin BV. Sex information given to Latina adolescents by parents. Health Education Research. 1995;10:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL. Child and young adolescent suicide in New Zealand. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):647–653. doi: 10.1080/0004867010060514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C, Bhana A, McKay M, Peterson I. Community collaborative partnerships: The foundation for HIV prevention research efforts. New York: Haworth Press; 2006. A Commentary on the Triadic Theory of Influence as a guide for adapting HIV prevention programs for new contexts and populations: The CHAMP-South Africa story. [Google Scholar]

- Bell C, Bhana A, Petersen I, McKay MM, Gibbons R, Bannon W, Amatya A. Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among Black youths: A randomized control trial. J Natl Med Asso. 2008;100(8):936–944. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CC, Flay B, Paikoff R. Strategies for health behavioral change. In: Chunn J, editor. The health behavioral change imperative: theory, education, and practice in diverse populations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Metzler CW, Wirt R, Ary D, Noell J, Ochs L, French C, Hood D. Social and behavioral factors associated with high-risk sexual behavior among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1990;13(3):245–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00846833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Ricardo IB, Stanton B. Social and psychological factors associated with AIDS risk behaviors among low-income, urban, African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1997;7(2):173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Pao M. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: A review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AE, Malone JD, Zhou SY, Lane JR, Hawkes CA. Human immunodeficiency virus RNA levels in US adults: a comparison based upon race and ethnicity. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(3):794–797. doi: 10.1086/517304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Danovsky MB, Lourie KJ, DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE. Adolescents with psychiatric disorders and the risk of HIV. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(11):1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Dolcini MM, Leventhal A. Transformations in peer relationships at adolescence: Implications for health related behaviors. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence. London: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and association with STD contraction. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(3):394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV/AIDS Surveillance report 2000. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV/AIDS Surveillance report 2008. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, Brouwers P, Heston J, Hodge J, DiPoalo V, Deygoo NS, Gadow KD. Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):627–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunn JC. The health behavioral change imperative: Theory, education, and practice in diverse populations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, Albino A. Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):390–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE, editors. Handbook of adolescent health risk behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Pao M. Understanding HIV/AIDS: psychosocial and psychiatric issues in youths. Contemporary Psychiatry. 2003;2:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry’s Role in a Changing Epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D. Societal exploitation. Adolescent Medicine. 1998;9(2):259–269. vi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-exposed youth: Roles of caregivers, peers and HIV status. Journal of Adolescent Health; 2009;45:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkington K, Robbins RN, Bauermeister JA, Abrams EJ, McKay M, Mellins CA. Mental health in youth infected, affected, and unaffected by HIV: The role of caregiver HIV. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(3):360–373. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis DA, Naar-King S, Cunningham PB, Secord E. Use of multisystemic therapy to improve antiretroviral adherence and health outcomes in HIV-infected pediatric patients: Evaluation of a pilot program. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:112–121. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. American Psychologist. 1991;46:931–936. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Snyder F, Petraitis J. The Theory of Triadic Influence. In: DiClemente RJ, Kegler MC, Crosby RA, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. Second ed. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 451–510. [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling RL, Bauman KE. Family structures as predictors of initial substance use and sexual intercourse in early adolescence. Journal of Marriage & Family. 1990;52:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Baugh D, McKay M. HIV/AIDs prevention with adolescents. In: Mullen EJ, editor. Oxford Bibliographies in Social Work. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Gretchen JD. Facing adolescence and adulthood: The importance of mental healthcare in the global pediatric AIDS epidemic. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(2):147–150. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318196b0cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DR, Azuma S, Chasnoff I. Three-year outcome of children exposed prenatally to drugs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:20–27. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer J, Mellins CA. Pediatric adherence to HIV antiretroviral. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2009;6:194–200. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Understanding resilient outcomes: adolescent lives across time and generations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Havens J, Mellins CA. Families. In: Smith RA, editor. Encyclopedia of AIDS: A social political, cultural, and scientific record of the epidemic. Chicago, IL and London, UK: Fitzroy-Dearborn, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Havens JF, Mellins CA, Ryan S, Locker A. Mental health needs of children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. In: Goodman H, Landsburg G, Spitz-Toth A, editors. mental health services for HIV impacted populations in New York City: A program perspective. New York, NY: The Coalition of Voluntary Mental Health Agencies, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Houck CD, Lescano CM, Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Thompson J, Diclemente R, et al. Islands of risk: Subgroups of adolescents at risk for HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(6):619–629. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inazu JK, Fox GL. Maternal influence on the sexual behavior of teenage daughters. Journal of Family Issues. 1980;(1):81–102. doi: 10.1177/0192513x8000100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RL. Growing up poor: the family experiences of socially mobile youth in low-income African-American neighborhoods. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1995;10:111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K. Oregon Social Learning Center. 1995. personal communication.

- Jordan K, Donenberg GR. Child and adolescent psychiatry and HIV/AIDS. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. 2006;18:545–550. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245356.68207.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katchadourian H. Feldman S, Elliot G. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. Sexuality; pp. 330–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick B, Armistead L, Forehand R. Adolescent sexual risk behavior. In: Wolfe DA, Mash EJ, editors. Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Adolescents: Nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Publications; 2006. pp. 563–588. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Strouthamer-Loeber M, Costello A, Farrington DP. Progression in antisocial and delinquent child behavior. Grant proposal (funded) to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, McKay M, Paikoff R, Bell C. Community collaboration and basic research: Necessary ingredient for the development of a family based HIV prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:75–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka SL, Farley JJ, Rodriguez JR, Sandrik LL, Sleasman JW, Tepper VJ. Clinical assessment of medication adherence among HIV-infected children: Examination of the Treatment Interview Protocol (TIP) AIDS Care. 2004;16:323–338. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001665330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka SL, Tepper VJ, Brown JL, Farley JJ. Caregiver psychosocial characteristics and children’s adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20:429–237. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka SL, Koenig LJ, Allison S, Bachanas P, Bulterys M, Bettica L, Tepper VJ, Abrams EJ. Family experiences with pediatric antiretroviral therapy: responsibilities, barriers, and strategies for remembering medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(8):637–647. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV, Gomez CA. Latino culture and sex: Implications for HIV prevention. In: Garcia JG, Zea MC, editors. Psychological interventions and research with Latino populations. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1997. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- McBride CK, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN. Family influences on the initiation of sexual activity among African American adolescents; Presented at the Role of Families in Preventing and Adapting to HIV/AIDS; Philadelphia, PA. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, McKinney L, Paikoff R. CHAMP Collaborative Board: Preventing HIV risk exposure in urban communities: The CHAMP family program. In: Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J, editors. Working with Families in the Era of HIV/AIDS. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Hibbert R, Lawrence R, Miranda A, Paikoff R, Bell C, Madison S, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Pinto R, Bannon W . CHAMP Collaborative Boards in New York & Chicago. Creating mechanisms for meaningful collaboration between members of urban communities and university-based HIV prevention researchers. In: McKay M, Paikoff R, editors. Community collaborative partnerships: The foundation for HIV prevention research efforts. New York: Haworth Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Paikoff R. Community collaborative partnerships: The foundation for HIV prevention research effort. New York: Haworth Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, McKinney LD, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, Bell CC. Family-level impact of the CHAMP family program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Fam Process. 2004;43(1):79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11):1035–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143646.15240.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu C-S, Elkington KS, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, McKay M, Bamji M, Abrams EJ. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, McKay M, Wiznia A, Bamji M, Abrams EJ. Sexual and drug use behavior in perinatally-HIV-infected youth: Mental health and family influences. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:810–819. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a81346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Havens JF, McDonnell C, Lichtenstein C, Udall K, Chesney M, Santamaria EK, Bell J. Adherence to antiretroviral medications and medical care in HIV-infected adults diagnosed with mental and substance abuse disorders. AIDS Care. 2009;21:68–177. doi: 10.1080/09540120802001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family environment scale manual. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Moscicki AB, Vermund SH, Muenz LR. Psychological distress among HIV(+) adolescents in the REACH study: effects of life stress, social support, and coping. The Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(6):391–398. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2011. 2012 Accessed at New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2002. 2002 Accessed at New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV epidemiology & field services program semiannual report. 2010 Available at: www.nyc.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff R, Traube D, McKay M. Overview of community collaborative partnerships and empirical findings: The foundation for HIV prevention research efforts in the United States and internationally. In: McKay M, Paikoff R, editors. Community collaborative partnerships: The foundation for HIV prevention research efforts. New York: Haworth Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, Wagener MM, Singh N. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;1333:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Mason A, Bhana A, Bell C, McKay M. Mediating social representations using a cartoon narrative in the context of HIV/AIDS: The AmaQhawe family project (CHAMP) in South Africa. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(2):197–208. doi: 10.1177/1359105306061180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2009;17(1):14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Black M, Ricardo I, Feigelman S, Kaljee L, Galbraith J, Nesbit R, Homik R, Stanton B. Social Influences on the Sexual Behavior of Youth at Risk of HIV Exposure. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(6):977–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer MA, Boyer CB. Psychosocial and behavioral factors associated with risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection, among urban high school students. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1991;119:826–833. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Steinhauer PD, Santa Barbaraa J. The family assessment measure. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1983;2:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Slonim-Nevo V, Auslander WF, Ozawa MN, Jung KG. The long-term impact of AIDS-preventive interventions for delinquent and abused adolescents. Adolescence. 1996;31(122):409–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Dore P, Earls F, Cunningham R. The influence of mental health problems on AIDS-related risk behaviors in young adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(5):314–320. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Bratslavsky E, Baumeister RF. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(1):53–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Henry D. Patterns of psychopathology among urban poor children: comorbidity and aggression effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Gil AG, Wagner EF, Artigues H. Patterns of sexual risk behaviors and psychiatric disorders in a community sample of young adults. J Behav Med. 2003;26(5):473–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1025776102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, Ragin DF, Cohall AT. Prevalence and correlates of AIDS-related behavioral intentions among urban minority high school students. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6(4):339–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, Cohall AT. Comparison of three theoretical models of substance use among urban minority high school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993a;32(5):975–981. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, Gladis MM, Ragin DF. Factors associated with AIDS-related behavioral intentions among high school students in an AIDS epicenter. Health Education Quarterly. 1993b;20(3):409–420. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, Cohall AT. Risk factors for substance use among high school students: implications for prevention. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):556–562. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild L, Flisher A, Bhana A, Lombard C. Associations among adolescent risk behaviors and self-esteem in six domains. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1454–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Kammerer B, Sirois PA, et al. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1745–e1756. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]