Abstract

The Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) gene VI product (P6) is a multifunctional protein essential for viral infection. In order to perform its various tasks, P6 interacts with both viral and host factors, as well as forming electron-dense cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. Here we investigate the interactions of P6 with three CaMV proteins: P2 (aphid transmission factor), P3 (virion-associated protein), and P7 (protein of unknown function). Based on yeast two-hybrid and maltose-binding protein pull-down experiments, P6 interacted with all three of these CaMV proteins. P2 helps to stabilize P6 inclusion bodies. Although the P2s from two CaMV isolates (W260 and CM1841) differ in the ability to stabilize inclusion bodies, both interacted similarly with P6. This suggests that inclusion body stability may not be dependent on the efficiency of P2–P6 interaction. However, neither P2 nor P3 interacted with P7 in yeast two-hybrid assays.

Keywords: P2, P3, P6, P7, CaMV, Aphid transmission factor, Caulimovirus, Movement, Translational transactivation (TAV), Virion-associated protein (VAP)

Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) is a plant pararetrovirus that is one of the top ten viruses in molecular plant pathology (Scholthof et al., 2011). The 8 kbp genome encodes seven potential polypeptides, designated P1–P7 (Haas et al., 2002; Hull, 2002). P7 is the first protein encoded by the 35S RNA, but the function of this molecule is unknown (Dixon et al., 1986). P1 serves as the cell-to-cell movement protein, while P2 serves as a factor permitting CaMV to be transmitted by aphids (Armour et al., 1983; Thomas et al., 1993). However, neither P1 nor P2 can bind to virus particles directly, but require interactions with another protein, P3 (also called virion-associated protein or VAP), that serves as a bridge linking P1 or P2 to virions (Leh et al., 2001; Stavolone et al., 2005). Thus, P3 binds to P4, the virus capsid protein. CaMV is a DNA virus that replicates through an RNA intermediate (Haas et al., 2002; Hull, 2002) and accomplishes this through a POL-like protein, similar to retro-viruses, which is the function of P5. P6 is the major protein making up electron-dense cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (IBs) (Covey and Hull, 1981) and it is responsible for many other functions as well. Interestingly, P2 influences the stability of P6 IBs (Anderson et al., 1992).

P6 IBs are thought to be the sites of virus genome replication, protein synthesis, and virus particle assembly/accumulation (Haas et al., 2002). Since P6 is the most abundant protein present within IBs and most viral functions occur within those structures, it is perhaps not surprising that the protein is multifunctional. P6 has been implicated in virtually every aspect of viral infection. P6 aids viral genome expression by permitting translation of all of the viral proteins from the 35S RNA through a process called translational transactivation (De Tapia et al., 1993). P6 appears to be involved in virus genome replication, movement and virus particle assembly (Kobayashi and Hohn, 2003; Schoelz et al., 1991; Himmelbach et al., 1996). The consequences of these processes are that P6 influences CaMV symptoms on virus-infected plants. P6 affects interactions with the host including influencing host range, and can impair plant defenses by inhibiting gene silencing (Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988; Love et al., 2007).

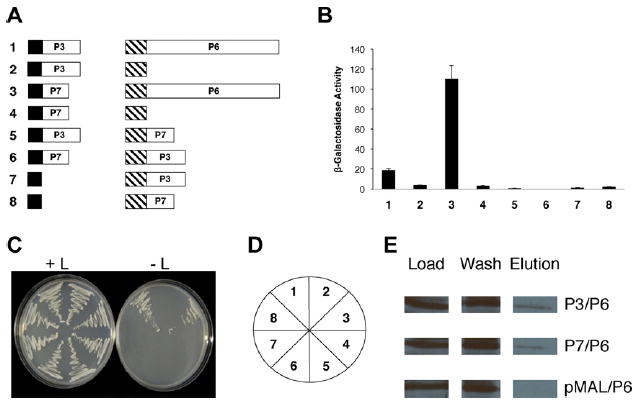

Since P6 may act as a molecular chaperone (Himmelbach et al., 1996) in virus particle assembly, we investigated whether P6 also interacted with P3, that is, associated with virions. CM1841 gene III was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), the primers 88G-1, 88G-2, and pCaMV10 (Gardner et al., 1981) as the template. All primer sequences used in this work are given in Supplementary Table 1. The PCR products were then inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites within the yeast two-hybrid vectors pEG202 and pJG4-5 (Gyuris et al., 1993). Full-length gene VI inserted in pJG4-5 was described earlier (Li and Leisner, 2002) as were the yeast transformation procedures. Yeast transformants expressing P3 fused to the LexA DNA binding domain (DBD) and P6 attached to the B42 transcription activation domain (TAD) grew on leucine-deficient media and exhibited β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 1). To confirm these interactions biochemically, the P3 coding region was amplified with the primers CaP3GWF and CaP3GWR. The PCR product was then inserted into Gateway-compatible pMAL-c2X (Raikhy et al., 2011) and maltose binding protein (MBP) pull-down assays were performed as described in (Hapiak et al., 2008). These data confirmed that P6 binds to P3.

Fig. 1.

Interaction of the gene III (P3) and gene VII products (P7) with the gene VI product (P6) of Cauliflower mosaic virus. (A) Diagram of constructs tested for interaction with the yeast two-hybrid system. Constructs are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); white boxes, full-length CaMV proteins; P3 (129 amino acids long), P6 (520 amino acids), and P7 (96 amino acids). Numbers in bold to the left of each pair of constructs correspond to β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and yeast growth in (C). (B) β-Galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructs shown in (A). The bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase activity (on abscissa) for β independent yeast colonies along with the standard deviation. Numbers at the bottom (ordinate) correspond to the transformants in C. (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left) and without (right) leucine. The streaks are numbered (key in (D)) to correspond to the constructs shown in (A) and the β-galactosidase activities shown in (B). (D) Key for the plates in (C). (E) Maltose binding protein pull-downs of P3 or P7 with P6. Load; amount of protein initially loaded onto column; flow-through, proteins that do not bind to the amylose column and are washed off; Elution, proteins eluting off the amylose resin. P3/P6, P3-maltose binding protein fusion polypeptide expressed in Escherichia coli, was mixed with P6 expressed in E. coli, loaded on an amylose column, eluted with maltose and probed with a P6 antibody. P7/P6, P7-maltose binding protein fusion polypeptide expressed in E. coli, was mixed with P6 expressed in E. coli, loaded on an amylose column, eluted with maltose and probed with a P6 antibody. pMAL/P6, maltose binding protein expressed in E. coli, was mixed with P6 expressed in E. coli, loaded on an amylose column, eluted with maltose and probed with a P6 antibody.

Our data, together with the observation that P6 stabilizes P3 in protoplasts (Kobayashi et al., 1998), suggest that the P3–P6 interaction plays a role in viral infection. Perhaps P6 aids in assembling capsids “decorated” with P3 by bringing P3 and P4 together. The P3 and P4 proteins are known to interact with each other (Leclerc et al., 2001). Such decorated virus particles could then associate with P1 to permit cell-to-cell movement.

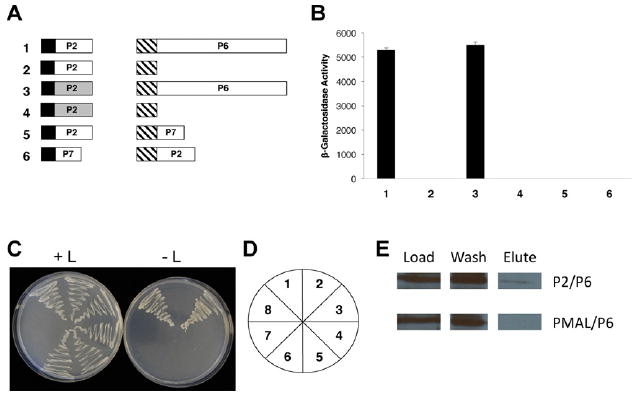

As a result of the interactions observed among P6, P1 (Hapiak et al., 2008) and P3 (described above), we hypothesized that the gene VI product also interacts with P2, which, in turn, interacts with P3 (Leh et al., 2001). CM1841 gene II was amplified by PCR using the CaP2GWF and CaP2GWR primers. The gene II product was inserted into Gateway-compatible pEG202, pJG4-5 or pMAL-c2X. Yeast transformants expressing gene II from CM1841 (expressed from pEG202) and CM1841 P6 (expressed from pJG4-5) grew on leucine-deficient media (Fig. 2) and showed β-galactosidase activity. The P2–P6 interaction was confirmed biochemically, by MBP pull-down experiments as described above.

Fig. 2.

Interaction of the gene II (P2) and gene VI products (P6) of Cauliflower mosaic virus. (A) Diagram of constructs tested for interaction with the yeast two-hybrid system. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain; hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain; white (CM1841 proteins) and gray (W260 proteins) boxes, full-length CaMV genes; P2 (159 amino acids long), P6 (520 amino acids), P7 (96 amino acids). Numbers in bold to the left of each pair of constructs correspond to β-galactosidase assay data shown in (B) and yeast growth in (C). (B) β-Galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructs shown in (A). (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left) and without (right) leucine. (D) Key for the plates in (C). (E) Maltose binding protein pull-downs of P2 with P6. P2/P6, P2-maltose binding protein fusion polypeptide expressed in Escherichia coli, was mixed with P6 expressed in E. coli, loaded on an amylose column, eluted with maltose and probed with a P6 antibody. pMAL/P6, maltose binding protein, was mixed with P6, loaded on an amylose column, eluted with maltose and probed with a P6 antibody.

P2 of CaMV isolate W260 was shown to have a greater stabilizing effect on P6 inclusion bodies than its CM1841 counterpart (Anderson et al., 1992). Therefore, we investigated if W260 P2 interacted with P6 in a manner different from its CM1841 counterpart. CaMV W260 gene II was amplified by PCR using the CaWP2F and CaWP2R primers with pCaMVW260 (Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988) as a template, then inserted into the EcoRI site of pEG202. Yeast transformants expressing W260 gene II (expressed from pEG202) and CM1841 P6 (expressed from pJG4-5) grew on leucine-deficient media (Fig. 2) and showed β-galactosidase activity. Interestingly, the W260 P2–P6 and CM1841 P2–P6 interactions were similar based on leucine-independent growth and β-galactosidase activity. Hence, a difference in interaction with P6 for the W260 and CM1841 P2s was not detected, even though the inclusion body stabilization mediated by the P2 proteins was different. One possible explanation for this, is that CM1841 P2 is less stable than its W260 counterpart (Blanc et al., 1993) and this characteristic rather than the P2–P6 interaction is responsible for the difference in IB stability.

Another important function of P6 is translational transactivation, the reinitiation of ribosomes on the polycistronic 35S RNA to make the various viral proteins (De Tapia et al., 1993). Interestingly, the first open reading frame on the 35S RNA encoding a polypeptide is the hypothetical gene VII product (P7). The majority of gene VII can be deleted without obvious effects on viral infection (Dixon et al., 1986). However, mutagenesis of the initiation codon delays viral symptoms and viruses harboring this mutation revert at a high frequency. While P7 can be expressed in yeast, it is undetectable in virus-infected plants, suggesting that it may be unstable (Wurch et al., 1990). Supporting this hypothesis is the observation that CaMV P5 protease cleaves P7 in vitro (Guidasci et al., 1992). Since P6 regulates CaMV translation and P7 is the first polypeptide encoded by the 35S RNA, we speculated that both proteins may interact.

To test this possibility, CM1841 gene VII was amplified using the primers GVII-1F and GVII-2R and inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites within the yeast two-hybrid vector pEG202. Yeast transformants expressing P7 (fused to the LexA DBD) and P6 (attached to the B42 TAD) grew on leucine-deficient media and exhibited β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 1). The P7 coding region was amplified with the primers CaP7GWF and CaP7GWR, inserted into Gateway-compatible pMAL-c2X and MBP pull-down assays were performed which confirmed P6 binds P7. By interacting with P6, P7 may permit the former protein to monitor translation efficiency and more appropriately regulate translational trans-activation. Alternatively, P7 may regulate the activity of the P5 protease as the first polypeptide encoded by some RNA viruses that process polyproteins is a regulator of the viral protease (Goldbach and Wellink, 1996). Yeast two-hybrid analyses failed to detect interactions of P2 or P3 with P7 (Figs. 1 and 2).

In summary, we have shown that P6 interacts with P2 and P3, two proteins essential for virus movement. We have also found that P6 interacts with a protein of unknown function, P7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Richard Komuniecki and Song-Tao Liu (University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA) for the vectors used in this study as well as Dr. Roger Brent (Molecular Sciences Institute, Berkeley, CA) for plasmids pEG202 and pJG4-5, along with yeast strain EGY48 harboring pSH18-34. This work was supported in part by NIH Grant number 1R15AI50641-01 and USDA-ARS Specific Cooperative Agreement: 58-3607-1-193.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2012.08.017.

References

- Anderson EJ, Trese AT, Sehgal OP, Schoelz JE. Characterization of a chimeric Cauliflower mosaic virus isolate that is more severe and accumulates to higher concentrations than either of the strains from which it was derived. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 1992;5:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Armour SL, Melcher U, Pirone TP, Lyttle DJ, Essenberg RC. Helper component for aphid transmission encoded by region II of Cauliflower mosaic virus DNA. Virology. 1983;129:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc S, Cerutti M, Chaabihi LC, Devauchelle G, Hull R. Gene II product of an aphid-nontransmissible isolate of Cauliflower mosaic virus expressed in a baculovirus system possesses aphid transmission factor activity. Virology. 1993;192:651–654. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey S, Hull R. Transcription of Cauliflower mosaic virus DNA. Detection of transcripts, properties, and location of the gene encoding the virus inclusion body protein. Virology. 1981;111:463–474. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tapia M, Himmelbach A, Hohn T. Molecular dissection of the Cauliflower mosaic virus translation transactivator. EMBO Journal. 1993;12:3305–3314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Jiricny J, Hohn T. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of Cauliflower mosaic virus DNA using a repair-resistant nucleoside analogue: identification of an agnogene initiation codon. Gene. 1986;41:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Howarth AJ, Hahn P, Brown-Luedi M, Shepherd RJ, Messing J. The complete nucleotide sequence of an infectious clone of Cauliflower mosaic virus by M13mp7 shotgun sequencing. Nucleic Acids Research. 1981;9:2871–2888. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.12.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach RW, Wellink J. Chapter 3: Comoviruses: molecular biology and replication. In: Harrison BD, Murant AF, editors. The Plant Viruses: Polyhedral Virions and Bipartite RNA Genomes. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. pp. 35–75. [Google Scholar]

- Guidasci T, Mougeot JL, Lebeurier G, Mesnard JM. Processing of the minor capsid protein of the Cauliflower mosaic virus requires a cysteine proteinase. Research in Virology. 1992;143:361–370. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(06)80124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M, Bureau M, Geldreich A, Yot P, Keller M. Cauliflower mosaic virus: still in the news. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2002;3:419–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapiak M, Li Y, Agama K, Swade S, Okenka G, Falk J, Khandekar S, Raikhy G, Anderson A, Pollock J, Zellner W, Schoelz J, Leisner SM. Cauliflower mosaic virus gene VI product N-terminus contains regions involved in resistance-breakage, self-association and interactions with movement protein. Virus Research. 2008;138:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelbach A, Chapdelaine Y, Hohn T. Interaction between Cauliflower mosaic virus inclusion body protein and capsid protein: implications for viral assembly. Virology. 1996;217:147–157. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull R. Matthews’ Plant Virology. Academic Press; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Hohn T. Dissection of Cauliflower mosaic virus transactiva-tor/viroplasmin reveals distinct essential functions in virus replication. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:8577–8583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8577-8583.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Tsuge S, Nakayashiki H, Mise K, Furusawa I. Requirement of Cauliflower mosaic virus open reading frame VI product for viral gene expression and multiplication in turnip protoplasts. Microbiology and Immunology. 1998;42:377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc D, Stavolone L, Meier E, Guerra-Peraza O, Herzog E, Hohn T. The product of ORF III in Cauliflower mosaic virus interacts with the coat protein through its C-terminal proline rich domain. Virus Genes. 2001;22:159–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1008121228637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leh V, Jacquot E, Geldreich A, Haas M, Blanc S, Keller M, Yot P. Interaction between the open reading frame III product and the coat protein is required for transmission of Cauliflower mosaic virus by aphids. Journal of Virology. 2001;75:100–106. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.100-106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Leisner SM. Multiple domains within the Cauliflower mosaic virus gene VI product interact with the full-length protein. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2002;15:1050–1057. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love AJ, Laird J, Holt J, Hamilton AJ, Sadanandom A, Milner JJ. Cauliflower mosaic virus protein P6 is a suppressor of RNA silencing. Journal of General Virology. 2007;88:3439–3444. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikhy G, Krause C, Leisner SM. The Dahlia mosaic virus gene VI product N-terminal region is involved in self-association. Virus Research. 2011;159:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholthof K-BG, Adkins S, Czosnek H, Palukaitis P, Jacquot E, Hohn T, Hohn B, Saunders K, Candresse T, Ahlquist P, Hemenway C, Foster GD. Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2011;12:938–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz JE, Shepherd RJ. Host range control of Cauliflower mosaic virus. Virology. 1988;162:30–37. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz JE, Goldberg KB, Kiernan J. Expression of Cauliflower mosaic virus CaMV gene VI in transgenic Nicotiana bigelovii complements a strain of CaMV defective in long-distance movement in nontransformed N. bigelovii. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 1991;4:350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stavolone L, Villani ME, Leclerc D, Hohn T. A coiled-coil interaction mediates Cauliflower mosaic virus cell-to-cell movement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:6219–6224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407731102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Perbal C, Maule AJ. A mutation of Cauliflower mosaic virus gene I interferes with virus movement but not virus replication. Virology. 1993;192:415–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurch T, Kirchherr D, Mesnard JM, Lebeurier G. The Cauliflower mosaic virus open reading frame VII product can be expressed in Saccha-romyces cerevisiae but is not detected in infected plants. Journal of Virology. 1990;64:2594–2598. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2594-2598.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.