Abstract

Redox-inactive metal ions that function as Lewis acids play pivotal roles in modulating the reactivity of oxygen-containing metal complexes and metalloenzymes, such as the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II and its small-molecule mimics. Here we report the synthesis and characterization of non-haem iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind redox-inactive metal ions, (TMC)FeIII–(μ,η2:η2-O2)–Mn+ (Mn+ = Sr2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+; TMC, 1,4,8,11-tetramethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane). We demonstrate that the Ca2+ and Sr2+ complexes showed similar electrochemical properties and reactivities in one-electron oxidation or reduction reactions. However, the properties and reactivities of complexes formed with stronger Lewis acidities were found to be markedly different. Complexes that contain Ca2+ or Sr2+ ions were oxidized by an electron acceptor to release O2, whereas the release of O2 did not occur for complexes that bind stronger Lewis acids. We discuss these results in the light of the functional role of the Ca2+ ion in the oxidation of water to dioxygen by the oxygen-evolving complex.

The redox-inactive Ca2+ ion is considered to be an essential cofactor in the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), the manganese–calcium–oxygen cluster (Mn4CaO5) that is the site of water oxidation in photosystem II (PSII)1–14. Several different functional roles have been proposed for this Ca2+ ion based on enzymatic and model reactions, such as modulation of the reduction potential of the manganese centre in the OEC and enhancement of the nucleophilic reactivity of water or hydroxide bound to Ca2+ ion7–14. Among redox-inactive metal ions, the Sr2+ ion is the only surrogate that restores the activity of OEC after Ca2+ removal11–17; a unique combination of similar sizes and Lewis acidities for Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions has been proposed for their dual abilities to function in OEC11–17.

Binding of redox-inactive metal ions to high-valent metal–oxo complexes was demonstrated recently in synthetic non-haem metal–oxo complexes of iron(IV), manganese(IV) and cobalt(IV)18–25, and the crystal structure of a Sc3+-bound [(TMC)FeIV(O)]2+ (TMC, 1,4,8,11-tetramethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane) complex was determined by X-ray crystallography18. It has been shown that reactivities of metal(IV)–oxo complexes are markedly affected by binding redox-inactive metal ions in various oxidation reactions21–25. More recently, it has been reported that a non-haem iron(III)–peroxo complex, [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ (ref. 26), binds redox-inactive metal ions (for example, Sc3+ and Y3+), which results in the generation of side-on iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind redox-inactive metal ions, [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –M3+ (M3+ = Sc3+ or Y3+)27,28. In another case, a crystal structure of a nickel–peroxo complex that binds the potassium ion, [LNi(μ,η2:η2-O2)K(solvent)], was obtained successfully29. However, binding of the Ca2+ ion (or Sr2+ ion) by metal–peroxo complexes has not been reported previously. In addition, the effect of redox-inactive metal ions on the chemical properties of metal–peroxo species has been investigated only rarely. Perhaps more important is that investigators who sought an explanation for the Ca2+ ion effect in PSII and its models focused solely on the O–O bond formation step and not on the metal–dioxygen species generated after O–O bond formation had occurred. Thus, it is timely to investigate the possibility of a Ca2+ ion effect inmodulating the chemical properties and reactivities of themetal–dioxygen (M–O2) species.

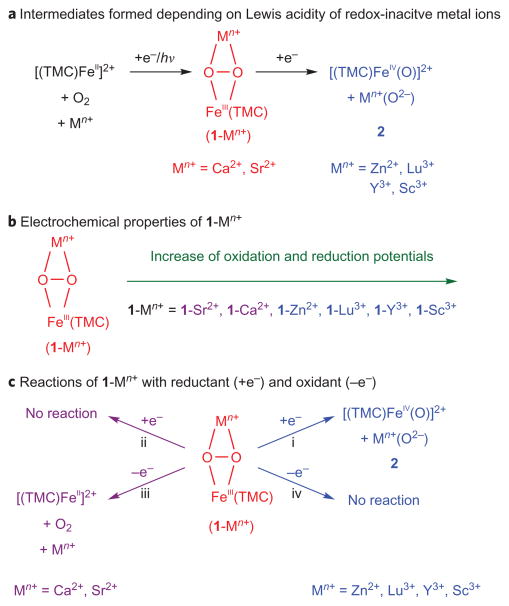

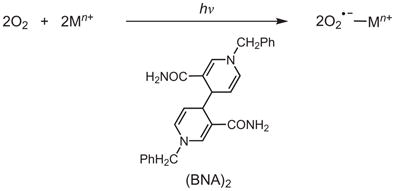

We report herein the formation of two different intermediates, [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Mn+ (1-Mn+) and [(TMC)FeIV(O)]2+ (2), in the photoinduced dioxygen activation by a non-haem iron complex in the presence of redox-inactive metal ions (Mn+ = Sr2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+) and an electron donor (for example, 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide dimer (BNA)2), depending on the Lewis acidity of metal ions: 1-Mn+ is the product when the redox-inactive metal ions are Sr2+ and Ca2+, whereas 2 is formed when the redox-inactive metal ions are Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+ (Fig. 1a). The electrochemical properties of 1-Mn+ were investigated using independently synthesized 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Sr2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+); both one-electron oxidation and reduction potentials of 1-Mn+ became more positive as the Lewis acidity of Mn+ increased (Fig. 1b). In the reaction of 1-Mn+ with a reductant (for example, (BNA)2), we observed the conversion of 1-Mn+ into 2 when Mn+ was Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+, whereas the conversion of 1-Mn+ into 2 did not occur when Mn+ was Sr2+ and Ca2+ (Fig. 1c). We also observed that 1-Mn+ reverted to [FeII(TMC)]2+ by releasing O2 on the addition of an oxidant, such as ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN), when Mn+ was Sr2+ or Ca2+, whereas the reaction of 1-Mn+ and CAN did not occur when Mn+ was Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ or Sc3+ (Fig. 1c). These latter results demonstrate unambiguously that the electrochemical properties and reactivities of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ are similar but very different from those of other 1-Mn+ complexes that bind redox-inactive metal ions with stronger Lewis acidities. We discuss these results in the light of the functional role(s) of Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions in water oxidation by OEC.

Figure 1. Iron(III)–peroxo complexes binding redox-inactive metal ions.

a, Intermediates 1-Mn+ and 2 formed in the photoirradiation reaction of a non-haem iron complex and O2 in the presence of redox-inactive metal ions (Mn+) and an electron donor. b, Electrochemical properties of 1-Mn+ depending on the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions. c, Effect of the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions on the reactions of 1-Mn+ with reductant (+e−) and oxidant (−e−). One-electron oxidation of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ by CAN leads to the release of O2, whereas other metal complexes, such as 1-Zn2+, 1-Lu3+, 1-Y3+ and 1-Sc3+, remain intact in the oxidation reaction. In contrast, the one-electron reduction of 1-Mn+ leads to the formation of 2 except in the reactions of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+.

Results and discussion

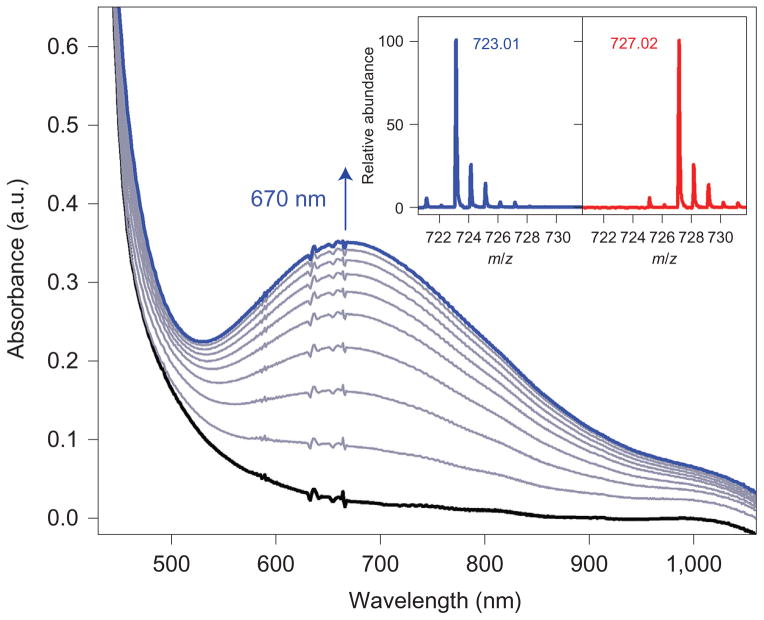

Iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind metal ions (1-Mn+)

It was shown previously that photoirradiation of an O2-saturated solution containing redox-inactive metal ions and (BNA)2 produces superoxo complexes of these redox-inactive metal ions (equation (1))30,31. Interestingly, when the photoirradiation reaction was performed with Ca(CF3SO3)2 and (BNA)2 in the presence of [(TMC)FeII]2+ in CH3CN at −20 °C, we observed the formation of an intermediate (1-Ca2+) with an absorption band at λmax = 670 nm (Fig. 2). Similarly, an intermediate (1-Sr2+) with an absorption band at λmax = 710 nm was formed when an identical reaction was performed using Sr(CF3SO3)2 instead of Ca (CF3SO3)2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ exhibit signals at g = 8.3, 4.3 and 3.3 for 1-Ca2+ and g = 9.4 and 4.3 for 1-Sr2+ (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3), which are indicative of high-spin (S = 5/2) Fe(III) species. The cold-spray ionization time-of-flight mass spectra (CSI-TOF MS) of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ exhibit a prominent ion peak at a mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of 723.01 for 1-Ca2+ (Fig. 2 inset, left panel) and 771.03 for 1-Sr2+ (Supplementary Fig. 1 inset, left panel), with mass and isotope distribution patterns that correspond to [(TMC)FeIII(O2)Ca (CF3SO3)2(CH3CN)]+ (calculated m/z, 723.02) and [(TMC) FeIII(O2)Sr(CF3SO3)2(CH3CN)]+ (calculated m/z, 771.02), respectively. The ion peaks of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ shifted four mass units on 18O-substitution (Fig. 2 inset, right panel for 1-Ca2+; Supplementary Fig. 1 inset, right panel for 1-Sr2+), which confirms that both 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ contain two oxygen atoms. By comparing these spectroscopic data with those of the previously reported [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –M3+ (M3+ = Sc3+ or Y3+) complexes27, we are able to assign 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ as [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Ca2+ and [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Sr2+, respectively (vide infra). It is proposed that the 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ complexes are formed in the reaction of [FeII(TMC)]2+ and O2•− –redox-inactive metal ions, as shown in equation (2).

Figure 2. Generation of 1-Ca2+ by O2 activation.

Absorption spectral changes in the photochemical reaction of [(TMC)FeII]2+ (0.50 mM) with O2 in the presence of (BNA)2 (2.5 mM) and Ca(CF3SO3)2 (10 mM) in MeCN at −20 °C; these show the formation of 1-Ca2+ with the absorption band at 670 nm. Insets show CSI-TOF MS spectra of 1-Ca2+ (left panel, blue line) and 18O-labelled 1-Ca2+ (right panel, red line) in MeCN at −40 °C. a.u., arbitrary units.

|

(1) |

| (2) |

In contrast, when the photochemical reaction was performed with redox-inactive metal ions, such as Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+, with Lewis acidities that are stronger than those of the Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions, we observed the formation of 2 rather than of 1-Mn+ (Supplementary Fig. 4; also see Fig. 1a for the formation of 2). These results suggest that the Lewis acidity of the redox-inactive metal ions (Supplementary Fig. 5)32 is an important factor that determines which product is formed in the photochemical reaction, such as the formation of 1-Mn+ in the case of Mn+ with a relatively weak Lewis acidity (for example, Ca2+ and Sr2+) versus the formation of 2 in the case of Mn+ with a relatively strong Lewis acidity (for example, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+) (Fig. 1a). We propose that 1-Mn+ is the common intermediate formed in the photoirradiation reaction irrespective of the redox-inactive metal ions (Fig. 1a). Then, 1-Mn+ is reduced further by (BNA)2 and the peroxo O–O bond of the reduced species, [(TMC)FeII(O2)]+ –Mn+, is cleaved heterolytically to give 2 in the case of Mn+ = Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+ (ref. 27), whereas the one-electron reduction of 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Ca2+ and Sr2+) by (BNA)2 does not occur and its peroxo O–O bond remains intact. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized [(TMC) FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Mn+ complexes independently and investigated their electrochemical properties as well as their reactions with a reductant (for example, (BNA)2) and an oxidant (for example, CAN).

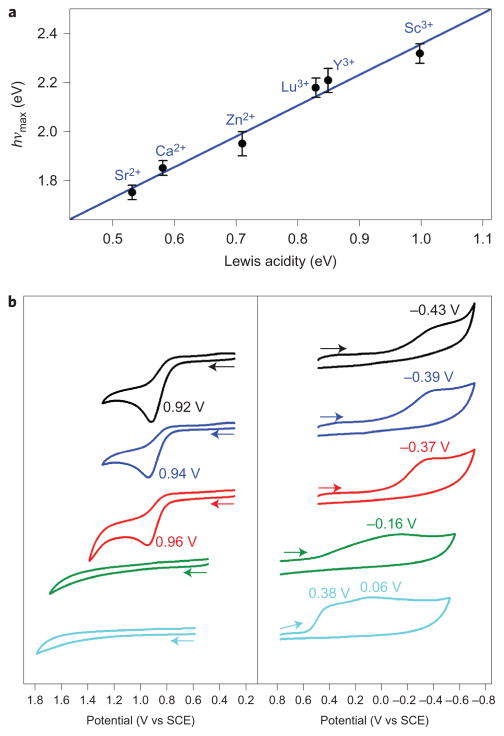

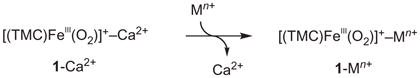

The [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Mn+ complexes were synthesized by reacting [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ with redox-inactive metal ions (equation (3); see the Supplementary Experimental Section and Supplementary Figs 6 and 7)27,28. Alternatively, the [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Mn+ complexes could be prepared by replacing the Ca2+ ion of 1-Ca2+ with redox-inactive metal ions of a stronger Lewis acidity (for example, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+) (equation (4); see the Supplementary Experimental Section), which is similar to the substitution of the Ca2+ ion by metal ions with a stronger Lewis acidity reported for heterometallic manganese–oxido clusters as a synthetic model of OEC8–10. The [(TMC)FeIII(μ,η2:η2-O2)]+ –Mn+ (1-Mn+) complexes were characterized with high confidence using various spectroscopic methods (see insets of Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1 for CSI-TOF MS spectra and Supplementary Figs 3 and 6–8 for EPR and ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis) spectra). In the electronic absorption spectra, we observed that the ligand-to-metal charge-transfer transition energy (hνmax) of 1-Mn+ increased linearly with increasing the Lewis acidity value of Mn+ (ΔE), determined from the gzz values of O2•−/Mn+ complexes (Fig. 3a; see Supplementary Fig. 8 for UV-vis spectra of 1-Mn+)32, which indicates that the ground state of the peroxo ligand in 1-Mn+ is stabilized with an increase in the Lewis acidity of the redox-inactive metal ions.

Figure 3. Effects of the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions bound to 1-Mn+.

a, Plot of hνmax of 1-Mn+ complexes obtained from electron absorption spectra versus Lewis acidity of metal ions (ΔE)32. The fitting was done through linear regression and the error bars indicate maximum absolute deviation. The plot indicates that the ligand-to-metal charge-transfer energy increases with an increase of Lewis acidity owing to the stabilizing ground state of the peroxo ligand in 1-Mn+. b, Cyclic voltammograms of 1 (black) and 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Sr2+ (blue), Ca2+ (red), Zn2+ (green) and Sc3+ (cyan)) in the one-electron oxidation (left panel) and one-electron reduction (right panel) processes in MeCN at −20 °C. Cyclic voltammograms show that one-electron oxidation of 1-Mn+ becomes more favourable with a decrease in the Lewis acidity of Mn+, whereas the one-electron reduction of 1-Mn+ is more favourable with an increase in the Lewis acidity of Mn+.

| (3) |

|

(4) |

As reported previously for the structural characterization of 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Sc3+ and Y3+) complexes27, the Fe K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) was measured for 1-Ca2+, 1-Sr2+ and 1-Zn2+ and the best-fit Fourier transform data are presented in Fig. 4 (see also Supplementary Figs 9 and 10, and Supplementary Table 1). 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ show minimal perturbation in the first shell coordination relative to 1, with two Fe–O at 1.92 Å and four Fe–N at 2.21 Å. No Fe–Ca2+ component was observed in 1-Ca2+, but a 4.18 Å Fe–Sr2+ contribution was required for 1-Sr2+. In contrast to 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+, the data for 1-Zn2+ are consistent with one Fe–O at 1.93 Å, four Fe–N at 2.21 Å and an intense Fe–Zn component at 4.02 Å. To address the experimentally observed structural differences between the three species, DFT geometry optimizations were performed for 1-Ca2+, 1-Sr2+ and 1-Zn2+ and correlated to the EXAFS data (details in the Supplementary Experimental Section). The results show that an η2–η2 bound FeIII–O2–M2+ species is formed on Ca2+ or Sr2+ binding. The first shells of the resulting molecules remain unperturbed relative to 1 (Supplementary Table 1), which indicates a weak 1-M2+ interaction in these systems. The optimized FeIII–M2+ distances and the FeIII–O–M2+ angles in 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ are 4.12 Å and 4.34 Å and 140° and 142°, respectively (Fig. 4a, b). The long distance and the steep multiple-scattering angle are consistent with the absence of an appreciable Fe–M2+ contribution in the EXAFS spectra for the lighter Ca2+, but it is observed for the heavier Sr2+. 1-Zn2+ optimizes to an η2–η1 Fe–O2–Zn2+ species, with an Fe–Zn of 4.04 Å and Fe–O–Zn angle at 163° (Fig. 4c). This shorter distance and wider angle forward focuses the Fe–Zn component, which results in a strong contribution to the EXAFS data.

Figure 4. EXAFS experiments and DFT geometry-optimized structures for 1-Ca2+, 1-Sr2+ and 1-Zn2+.

Non-phase-shift-corrected Fourier transforms and the corresponding EXAFS data for 1-Ca2+, 1-Sr2+ and 1-Zn2+: a, FEFF best-fit (blue) to 1-Ca2+ (black). b, FEFF best-fit (violet) to 1-Sr2+ (black). c, FEFF best-fit (red) to 1-Zn2+ (black). Insets show the corresponding DFT geometry-optimized structures for 1-Ca2+, 1-Sr2+ and 1-Zn2+. The distances obtained from EXAFS are shown (red) for comparison with the DFT distances (black). Average Fe–N distances are shown. DFT calculated FeIII–O–M2+ angles are given in parenthesis next to the Fe–M2+ distances. NA, not applicable.

Electrochemical properties of 1-Mn+

We then determined the electrochemical properties of 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Sr2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+). First, the cyclic voltammogram of 1 in a one-electron oxidation process is shown in Fig. 3b (left panel, black line), in which the anodic current peak (Epa) caused by the oxidation of 1 is observed at 0.92 V versus a saturated calomel electrode (SCE). No corresponding cathodic current peak (Epc) was observed at the reverse scan, which indicates that the oxidation of 1 was irreversible because of the release of O2 on one-electron oxidation (vide infra). In the case of 1-Ca2+, the Epa value was shifted in a slightly positive direction (Epa = 0.96 V versus SCE; Fig. 3b, left panel, red line). A similar Epa value was observed for 1-Sr2+ (Epa = 0.94 V versus SCE; Fig. 3b, left panel, blue line). In the cases of 1-Zn2+ and 1-Sc3+, however, no oxidation peak was observed up to 1.7 V versus SCE (Fig. 3b, left panel, green and cyan lines). In the cyclic voltammogram of 1 for the one-electron reduction process (Fig. 3b, right panel, black line), the cathodic current peak (Epc) caused by the reduction of 1 was observed at −0.43 V versus SCE, but no corresponding anodic current peak (Epa) was observed at the reverse scan, which indicated that the one-electron reduction of 1 was irreversible because of the O–O bond cleavage of the one-electron reduced species to form the FeIV(O) complex 2 (ref. 27). Similar Epc values were observed for 1-Sr2+ and 1-Ca2+ (Fig. 3b, right panel, blue and red lines). The Epc value was shifted to the positive direction for 1-Zn2+ (Epc = −0.16 V versus SCE; Fig. 3b, right panel, green line). In the case of 1-Sc3+ (Fig. 3b, right panel, cyan line), the Epc value was shifted further to 0.38 V versus SCE and one additional cathodic current peak was observed at ~0.06 V versus SCE, which was assigned as the cathodic current peak of [(TMC)FeIV(O)]2+ (Supplementary Fig. 11)33. Moreover, the Epc values for 1-Y3+ and 1-Lu3+ were between those for 1-Sc3+ and 1-Zn2+ (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results indicate that the one-electron oxidation and reduction potentials of 1-Mn+ vary depending on the Lewis acidity of Mn+ and that the one-electron oxidation of 1-Mn+ becomes more favourable with a decrease of the Lewis acidity of Mn+, whereas the one-electron reduction of 1-Mn+ is more favourable with an increase of the Lewis acidity of Mn+. Further, as we propose above, the one-electron oxidation and reduction reactions of 1-Mn+ afford the release of the bound O2 unit and the O–O bond cleavage of the peroxo group in 1-Mn+ to give 2, depending on the Lewis acidity of Mn+ in 1-Mn+. This prediction is confirmed by performing chemical reduction and oxidation reactions of 1-Mn+ with electron donor and acceptor (vide infra).

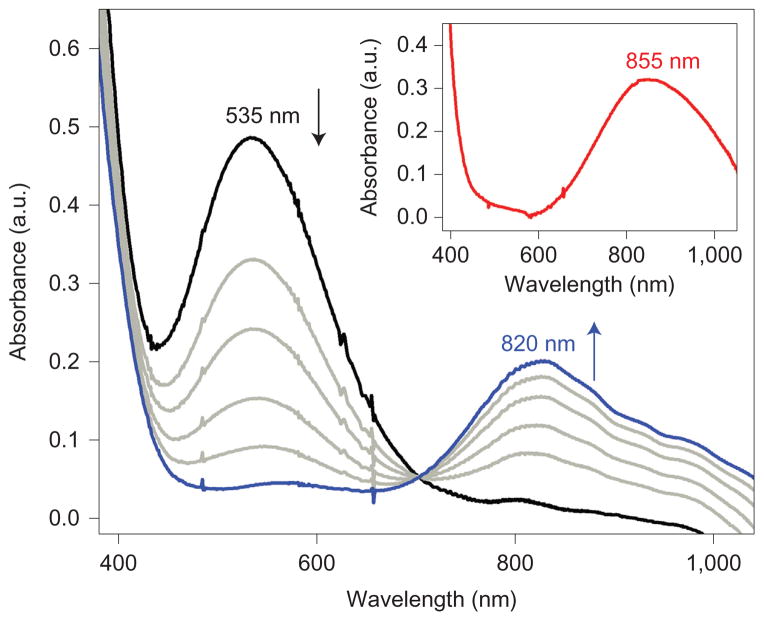

Reduction and oxidation reactions of 1-Mn+

As described above, the redox reactivity of 1-Mn+ is affected significantly by the Lewis acidity of Mn+ bound to the iron(III)–peroxo complex. For example, although no thermal reaction occurred on the addition of (BNA)2 to the solution of 1 (Fig. 5 inset), the addition of Sc3+ ions into the solution of 1 in the presence of (BNA)2 resulted in the rapid formation of 1-Sc3+ (Fig. 5, black line), followed by the conversion of 1-Sc3+ into 2 (Fig. 5, blue line) with a clear isosbestic point at 700 nm. When 1-Sc3+, 1-Y3+, 1-Lu3+ and 1-Zn2+ complexes generated in situ were reacted with (BNA)2, the formation of 2 was observed (see reaction i in Fig. 1c). In contrast, 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ did not react with (BNA)2 and no formation of 2 was observed (see reaction ii in Fig. 1c). These results demonstrate that the one-electron reduction of 1-Mn+ depends on the Lewis acidity of the redoxinactive metal ions. Thus, 1-Mn+ with a relatively strong Lewis acidity of Mn+ (for example, Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+) is reduced readily by (BNA)2, and the one-electron reduced species [(TMC)FeII(O2)]–Mn+ is converted into 2 via O–O bond cleavage (see reaction i in Fig. 1c), as we have proposed previously27. In contrast, 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ are not reduced by the electron donor, and no further reaction, such as O–O bond cleavage, takes place (see reaction ii in Fig. 1c). The present results are consistent with the trend of the one-electron reduction peak potentials of 1-Mn+ (see Fig. 3b, right panel); 1-Mn+ with a more-positive reduction peak potential is readily reduced by (BNA)2 to give 2, such as in the cases of Mn+=Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+ (see Fig. 1b and reaction i in Fig. 1c), whereas 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+, with relatively negative reduction peak potentials, are not reduced by (BNA)2 and remain intact (see Fig. 1b and reaction ii in Fig. 1c).

Figure 5. Conversion of 1-Sc3+ into 2 by electron transfer.

UV-vis spectral changes observed in the reaction of 1-Sc3+ (0.5 mM) with (BNA)2 (2.0 mM) in MeCN at −20 °C (black line). The disappearance of the peak at 535 nm with the concomitant appearance of the peak at 820 nm indicates the conversion of 1-Sc3+ into 2. The inset shows the UV-vis spectrum of isolated [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ (0.50 mM) in the presence of (BNA)2 (2.0 mM) in MeCN at −20 °C, which demonstrates that no reaction takes place on one-electron reduction of 1.

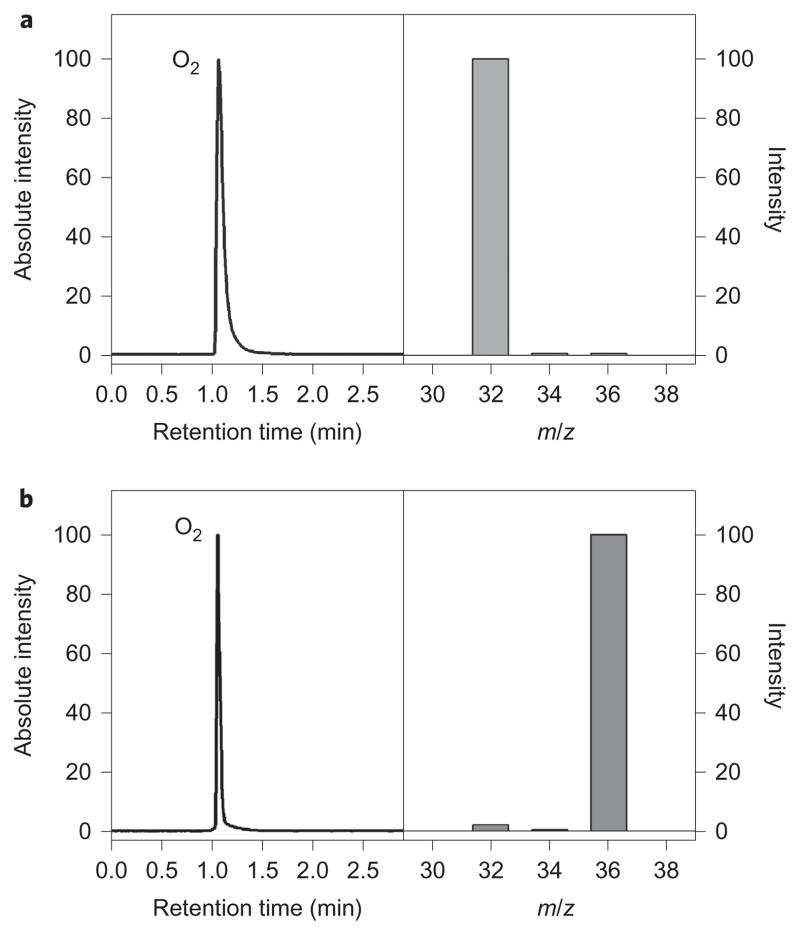

The electron-transfer oxidation of 1-Mn+ was also examined using CAN as an oxidant (Supplementary Fig. 13). On the addition of 1 equiv. CAN to the solutions of 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+, the intermediates disappeared immediately and the formation of [(TMC)FeII]2+ was detected by an electrospray ionization mass spectrometer and EPR (Supplementary Figs 13 and 14; also see the Supplementary Experimental Section). Importantly, the release of O2 was detected by gas chromatography (GC) (Supplementary Fig. 15) and GC/MS in these reactions (Fig. 6a). To confirm the source of O2, 18O-labelled 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ complexes were prepared and reacted with CAN, and the 18O2 product was analysed by GC/MS (Fig. 6b). These results demonstrate unambiguously that 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ were oxidized by CAN and the peroxo ligand in 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ was released as O2 (see reaction iii in Fig. 1c). Similarly, the oxidation of 1 on the addition of 1 equiv. CAN afforded the formation of [(TMC) FeII]2+ with the release of O2, which suggests that the binding of Ca2+ and Sr2+ to 1 does not influence the release of O2 greatly. In contrast, no reaction took place when 1-Mn+ (Mn+ = Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+) was reacted with CAN (see reaction iv in Fig. 1c, and Supplementary Figs 13 and 16). These results are interpreted with the Epc values of 1 and 1-Mn+ in the one-electron oxidation process. Electron transfer from 1, 1-Ca2+ and 1-Sr2+ to CAN is thermodynamically feasible, as indicated by the Epc values of 1 (Epc = 0.92 V versus SCE), 1-Ca2+ (Epc = 0.96 V versus SCE) and 1-Sr2+ (Epc = 0.94 V versus SCE), which are significantly less positive than the Ered value of CAN (1.37 V versus SCE)34. In the cases of 1-Zn2+ and 1-Sc3+, the Epa values of 1-Zn2+ and 1-Sc3+ (>1.7 V versus SCE; see Fig. 3b) are much more positive than the Ered value of CAN (1.37 V versus SCE)34. Therefore, no electron transfer from 1-Zn2+ and 1-Sc3+ to CAN occurs in the latter reaction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions is an important factor that determines the one-electron oxidation process and release of O2 from the iron(III)–peroxo complexes, 1-Mn+ (reactions iii and iv in Fig. 1c).

Figure 6. Analysis of the O2 product.

a, b, GC/MS spectra of 16O2 and 18O2 produced in the reactions of [(TMC)FeIII(16O2)]+ –Ca2+ (0.50 mM) with CAN (1.0 mM) (a) and [(TMC)FeIII(18O2)]+ –Ca2+ (0.50 mM) with CAN (1.0 mM) in MeCN at −20 °C (b). The mass spectra obtained in these reactions clearly indicate that the source of O2 is, indeed, from 1-Ca2+.

Concluding remarks

The roles of Ca2+ ion in water oxidation by OEC and its models were considered to enhance the nucleophilic reactivity of water or hydroxide bound to a Ca2+ ion in making the O–O bond with a presumed high-valent manganese–oxo intermediate. Very recently, Agapie and co-workers proposed that one possible role of the Ca2+ ion in OEC is to modulate the reduction potential of the manganese centre to allow electron transfer; the reduction potentials of heterometallic manganese–oxido clusters that contain Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions are the same and the reduction potentials of the manganese–oxido clusters are correlated linearly with the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions. In the present study, we demonstrate that the Lewis acidity of redox-inactive metal ions is an important factor that determines the electrochemical properties of metal(III)–peroxo complexes as well as their reactivities in chemical reactions with electron donors and acceptors. For example, the electrochemical properties of iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind Ca2+ or Sr2+ ions are similar and the electrochemical properties of iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind redox-inactive metal ions are modulated by the Lewis acidity of the redox-inactive metal ions. More importantly, iron(III)–peroxo complexes that bind Ca2+ or Sr2+ ions are oxidized by an oxidant to release O2, whereas the release of O2 does not occur in the case of iron(III)–peroxo complexes binding redox-inactive metal ions with a stronger Lewis acidity than the Ca2+ or Sr2+ ions (Fig. 1c, reactions iii and iv). Considering that the last step of water oxidation in the Kok cycle is to release O2 by one-electron oxidation of manganese–peroxo (or –hydroperoxo) species (that is, the S4 to S0 transition)35, our results suggest that the O2-release step in the Kok cycle is controlled by the Lewis acidity of the redox-inactive metal ions (for example, Ca2+ or Sr2+ ions) binding to the manganese–peroxo (or –hydroperoxo) species. We therefore propose that, in addition to the previously proposed role(s) of the Ca2+ (or Sr2+) ion in facilitating the O–O bond-making process, one reason to use the Ca2+ (or Sr2+) ion in OEC is to release O2 by controlling the redox potential of the manganese–peroxo (or –hydroperoxo) species. In other words, redox-inactive metal ions, such as Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions, may not facilitate the O2-release process, but at least should not interfere with the O2-release step after O–O bond formation occurs. Thus, the present results may provide at least a partial answer to the questions of why nature does not choose a stronger Lewis acidic redox-inactive metal ion (for example, Zn2+) but instead chooses the Ca2+ ion in the oxidation of water to evolve O2 and why the Sr2+ ion is the only surrogate to replace the Ca2+ ion for the reactivity of the OEC in PSII.

Methods

Materials

[(TMC)FeII(CH3CN)2](CF3SO3)2, [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ (1) and [(TMC) FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+ (2) were prepared according to methods described in the literature18,26. [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ (1) was generated by reacting [(TMC) FeII(CF3SO3)2] (69.3 mg, 0.10 mmol) with 5 equiv. H2O2 (51 μl, 30% in water, 0.50 mmol) in the presence of 2 equiv. triethylamine (TEA) (28 μl, 0.20 mmol) in CF3CH2OH (2 ml) at −40 °C. Then Et2O (40 ml) was added to the solution of [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ to yield a purple precipitate at −40 °C. This purple precipitate was washed with Et2O and dried under an Ar atmosphere. Similarly, [(TMC)FeIII(18O2)]+ was also prepared by adding 5 equiv. H2 18O2 (90% 18O-enriched, 2% H2 18O2 in water) to a solution that contained [(TMC)FeII]2+ and 2 equiv. TEA in CF3CH2OH at −40 °C.

Generation of [(TMC)FeIII(O2)]+ –Mn+ (1-Mn+)

1-Mn+ complexes were generated by adding metal triflate [Mn+(CF3SO3)n] (Mn+ = Sc3+ (1.0 equiv.), Y3+ (1.0 equiv.), Lu3+ (3.0 equiv.), Zn2+ (10 equiv.), Ca2+ (10 equiv.) and Sr2+ (10 equiv.)) to a solution of isolated 1 in acetonitrile at −20 °C (ref. 27). 18O-labelled 1-Mn+ complexes were generated using isolated [(TMC)FeIII(18O2)]+ under identical reaction conditions. Alternatively, 1-Mn+ complexes were prepared by reacting 1-Ca2+ with a metal triflate [Mn+(CF3SO3)n] of stronger Lewis acidity than Ca2+ ion in acetonitrile (MeCN) at −20 °C.

Dioxygen activation

UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett Packard Agilent 8453 UV–visible spectrophotometer equipped with a circulating water bath or an UNISOKU cryostat system (USP-203; UNISOKU, Japan). Dioxygen activation by [(TMC)FeII]2+ was examined by monitoring spectral changes at 670 nm caused by 1-Ca2+ for the Ca2+ ion, at 710 nm caused by 1-Sr2+ for the Sr2+ ion and at 820 nm caused by [(TMC)FeIV(O)]2+ (2) for the Zn2+, Lu3+, Y3+ and Sc3+ ions in the reaction of [(TMC)FeII]2+ (0.50 mM) with (BNA)2 (0.50–2.5 mM) and metal triflate [Mn+(CF3SO3)n] (Mn+ = Sc3+ (1.0 equiv.), Y3+ (1.0 equiv.), Lu3+ (3.0 equiv.) and Zn2+ (10 equiv.)) in O2-saturated MeCN at −40 °C.

Reaction of 1-Mn+ with CAN

A vial (5.0 ml) that contained a solution of 1-Ca2+ (0.50 mM, 2.0 ml) in MeCN and another vial that contained CAN (1.0 mM) in MeCN were sealed with a rubber septum. The two vials were deaerated carefully by bubbling Ar gas for 15 minutes at −20 °C. The solution that contained CAN was taken and injected into the vial that contained 1-Ca2+ via a syringe piercing through the rubber septum. After five minutes, the reaction solution was warmed to 20 °C and 100 μl Ar gas was injected into the vial, and then the same volume of gas in the headspace of the vial was sampled out by a gas-tight syringe and quantified by a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector at 40 °C. Products were identified by comparing them with authentic samples, and the yields were determined by comparison against standard curves from these authentic samples.

18O-labelling experiments by GC/MS

A vial (5.0 ml) that contained a solution of 1-Ca2+ or 18O-labelled 1-Ca2+ (0.5 mM, 2.0 ml) in MeCN and another vial that contained CAN (1.0 mM) in MeCN were sealed with a rubber septum. The two vials were deaerated carefully by bubbling He gas for 20 minutes at −20 °C. The solution that contained CAN was taken and injected into the vial that contained 1-Ca2+ via a syringe piercing through the rubber septum. After five minutes, the reaction solution was warmed to 20 °C and 100 μl headspace gas was sampled out for gas analysis. The ratios of 16O16O, 16O18O and 18O18O were determined based on the intensities of mass peaks at m/z = 32, 34 and 36, analysed by a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph equipped with a Shimadzu QP-5000 mass spectrometer at 40 °C.

The experimental section in the Supplementary Information gives full experimental details, procedures, calculation details and spectroscopic and product analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by KOSEF/MEST of Korea through the CRI (NRF-2012R1A3A2048842 to W.N.), GRL (NRF-2010-00353 to W.N.) and MSIP of Korea through NRF (2013R1A1A2062737 to K-B.C.) and an ALCA project from JST (S.F.) from MEXTof Japan. Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) operations are funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE) Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology program is supported by National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (P41 RR001209) and DOE Biological Environmental Research (R.S.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

W.N. conceived and designed the experiments; S.B., Y-M.L., S.H., K-B.C., Y.N. and M.S.S. performed the experiments; Y-M.L., R.S., S.F., S.B., K-B.C., M.S.S. and S.H. analysed the data; W.N., S.F., Y-M.L., R.S. and K-B.C. co-wrote the paper.

Supplementary information and chemical compound information are available in the online version of the paper.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hammarström L, Hammes-Schiffer S. Artificial photosynthesis and solar energy. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1859–1860. doi: 10.1021/ar900267k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nocera DG. The artificial leaf. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:767–776. doi: 10.1021/ar2003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivalta I, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Oxomanganese complexes for natural and artificial photosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J. Towards complete cofactor arrangement in the 3.0 Å resolution structure of photosystem II. Nature. 2005;438:1040–1044. doi: 10.1038/nature04224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen J-R, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature. 2011;473:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanady JS, Tsui EY, Day MW, Agapie T. A synthetic model of the Mn3Ca subsite of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Science. 2011;333:733–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1206036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsui EY, Tran R, Yano J, Agapie T. Redox-inactive metals modulate the reduction potential in heterometallic manganese–oxido clusters. Nature Chem. 2013;5:293–299. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanady JS, et al. Oxygen atom transfer and oxidative water incorporation in cuboidal Mn3MOn complexes based on synthetic, isotopic labeling, and computational studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1073–1082. doi: 10.1021/ja310022p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsui EY, Agapie T. Reduction potential of heterometallic manganese–oxido cubane complexes modulated by redox inactive metals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:10084–10088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox N, Pantazis DA, Neese F, Lubitz W. Biological water oxidation. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:1588–1596. doi: 10.1021/ar3003249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yachandra VK, Yano J. Calcium in the oxygen-evolving complex: structural and mechanistic role determined by X-ray spectroscopy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011;104:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillier W, Wydrzynski T. 18O-water exchange in photosystem II: substrate binding and intermediates of the water splitting cycle. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yocum CF. The calcium and chloride requirements of the O2 evolving complex. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:296–305. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox N, et al. Effect of Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution on the electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: a combined multifrequency EPR, 55Mn-ENDOR, and DFT study of the S2 state. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3635–3648. doi: 10.1021/ja110145v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishida N, et al. Biosynthetic exchange of bromide for chloride and strontium for calcium in the photosystem II oxygen-evolving enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13330–13340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vrettos JS, Stone DA, Brudvig GW. Quantifying the ion selectivity of the calcium site in photosystem II: evidence for direct involvement of Ca2+ in O2 formation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7937–7945. doi: 10.1021/bi010679z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuzumi S, et al. Crystal structure of a metal ion-bound oxoiron(IV) complex and implications for biological electron transfer. Nature Chem. 2010;2:756–759. doi: 10.1038/nchem.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, et al. A mononuclear non-heme manganese(IV)–oxo complex binding redox-inactive metal ions. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6388–6391. doi: 10.1021/ja312113p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leeladee P, et al. Valence tautomerization in a high-valent manganese–oxo porphyrinoid complex induced by a Lewis acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10397–10400. doi: 10.1021/ja304609n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaff FF, et al. An oxocobalt(IV) complex stabilized by Lewis acid interactions with scandium(III) ions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1711–1715. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morimoto Y, et al. Metal ion-coupled electron transfer of a nonheme oxoiron(IV) complex: remarkable enhancement of electron-transfer rates by Sc3+ J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:403–405. doi: 10.1021/ja109056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Morimoto Y, Lee Y-M, Nam W, Fukuzumi S. Metal ion effect on the switch of mechanism from direct oxygen transfer to metal ion-coupled electron transfer in the sulfoxidation of thioanisoles by a non-heme iron(IV)–oxo complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5236–5239. doi: 10.1021/ja200901n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Morimoto Y, Lee Y-M, Nam W, Fukuzumi S. Proton-promoted oxygen atom transfer vs proton-coupled electron transfer of a non-heme iron (IV)–oxo complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3903–3911. doi: 10.1021/ja211641s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon H, et al. Enhanced electron-transfer reactivity of nonheme manganese(IV)–oxo complexes by binding scandium ions. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9186–9194. doi: 10.1021/ja403965h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho J, et al. Structure and reactivity of a mononuclear non-haem iron(III)–peroxo complex. Nature. 2011;478:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature10535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Y-M, et al. A mononuclear nonheme iron(III)–peroxo complex binding redox-inactive metal ions. Chem Sci. 2013;4:3917–3912. doi: 10.1039/C3SC51864G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li F, Van Heuvelen KM, Meier KK, Münck E, Que L., Jr Sc3+-triggered oxoiron(IV) formation from O2 and its non-heme iron(II) precursor via a Sc3+–peroxo–Fe3+ intermediate. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10198–10201. doi: 10.1021/ja402645y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao S, et al. O–O bond activation in heterobimetallic peroxides: synthesis of the unique peroxide [LNi(μ,η2:η2-O2)K] and its conversion to a bis(μ-hydroxo) Ni–Zn complex. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:8107–8110. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukuzumi S, Patz M, Suenobu T, Kuwahara Y, Itoh S. ESR spectra of superoxide anion–scandium complexes detectable in fluid solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1605–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawashima T, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S. Stepwise vs. concerted pathways in scandium ion-coupled electron transfer from superoxide ion to p-benzoquinone derivatives. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:3344–3352. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00916d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K. Quantitative evaluation of Lewis acidity of metal ions derived from the g values of ESR spectra of superoxide: metal ion complexes in relation to the promoting effects in electron transfer reactions. Chem Eur J. 2000;6:4532–4535. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001215)6:24<4532::aid-chem4532>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y-M, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Nam W, Fukuzumi S. Fundamental electron-transfer properties of non-heme oxoiron(IV) complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:434–435. doi: 10.1021/ja077994e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong D, et al. Water oxidation catalysis with nonheme iron complexes under acidic and basic conditions: homogeneous or heterogeneous. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:9522–9531. doi: 10.1021/ic401180r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kok B, Forbush B, McGloin M. Cooperation of changes in photosynthetic O2 evolution. 1 A linear four step mechanism. Photochem Photobiol. 1970;11:457–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.