Abstract

To analyze the learning curve for cancer control from an initial 250 cases (Group I) and subsequent 250 cases (Group II) of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP) performed by a single surgeon. Five hundred consecutive patients with clinically localized prostate cancer received RALP and were evaluated. Surgical parameters and perioperative complications were compared between the groups. Positive surgical margin (PSM) and biochemical recurrence (BCR) were assessed as cancer control outcomes. Patients in Group II had significantly more advanced prostate cancer than those in Group I (22.2% vs 14.2%, respectively, with Gleason score 8–10, P= 0.033; 12.8% vs 5.6%, respectively, with clinical stage T3, P= 0.017). The incidence of PSM in pT3 was decreased significantly from 49% in Group I to 32.6% in Group II. A meaningful trend was noted for a decreasing PSM rate with each consecutive group of 50 cases, including pT3 and high-risk patients. Neurovascular bundle (NVB) preservation was significantly influenced by the PSM in high-risk patients (84.1% in the preservation group vs 43.9% in the nonpreservation group). The 3-year, 5-year, and 7-year BCR-free survival rates were 79.2%, 75.3%, and 70.2%, respectively. In conclusion, the incidence of PSM in pT3 was decreased significantly after 250 cases. There was a trend in the surgical learning curve for decreasing PSM with each group of 50 cases. NVB preservation during RALP for the high-risk group is not suggested due to increasing PSM.

Keywords: cancer control, learning curve, prostate cancer, prostatectomy, robotics, surgical margin

INTRODUCTION

The gold standard for treatment of localized prostate cancer is retropubic radical prostatectomy (RRP). The ultimate goal of RRP is to eliminate the cancer and cure the patient. The RRP technique is difficult to master. As a surgeon gains more experience, the incidence of a positive surgical margin (PSM) is reduced, and an improvement in cancer control is usually achieved after 250 cases of RRP.1 The predicted probabilities of biochemical recurrence rate (BCR) at 5 years were 17.9% for patients treated by surgeons with 10 prior operations and 10.7% for patients treated by surgeons with 250 prior operations (difference = 7.2%, 95% confidence interval [CI] =4.6%–10.1%; P < 0.001).1 The learning curve for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) was reported to be slower than that reported previously for open surgery.2 The 5-year risk of BCR decreased from 17% to 16% even 9% for patients treated by a surgeon with 10, 250, and 750 prior laparoscopic procedures, respectively (risk difference between 10 and 750 procedures 8.0%, 95% CI 4.4–12.0).2 LRP seems to involve skills that do not translate well from RRP.2 Herrell and Smith3 in their study have reported robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP) results comparable to those obtained routinely with RRP were not achieved until a surgeon performed more than 150 procedures. The comfort level and confidence of surgeons was not comparable to that with RRP until 250 RALP procedures were performed.3

The learning curve with RALP for surgical margin has been reported previously.4,5,6,7,8 Atug et al.4 in their study found that as a surgeon's experience increased beyond approximately 30 cases, the incidence of PSM tended to decline from 45.4% to 21.2% or 11.7%. Ahlering et al.5 reported PSM reduced from 36% for surgeons who had performed up to 50 procedures, and to 16.7% for those performing between 51 and 140 procedures. Patel et al.6 reported on 1500 case of RALP, in which the incidence of PSM for surgeons with experience of 1–300, 301–600, 601–900, 901–1200, and 1201–1500 cases were 12.2%, 6.6%, 13.6%, 11.0%, and 1.8%, respectively. Zorn et al.7 reported PSM was 15% at 1–300 cases, 10% at 301–500 cases, and 7% at 501–700 cases, statistically significant decreases. Previously, we reported that over the first 100 cases of RALP, the incidence of PSM in pathologic stage T3 (pT3) prostate cancer was not significantly reduced. A learning curve of more than 100 cases is required to decrease the PSM incidence in pT3 tumors.9 We also published the trifecta outcome in 300 consecutive cases of RALP according to D’Amico risk criteria. The PSM was 37% and BCR was 13.7% at a mean follow-up of 30.6 months, and the series included more high-risk patients (the incidence of low, intermediate, and high was 21.2%, 29.3%, and 49.3%, respectively).10 The objective of this study was to analyze the surgical learning curve for cancer control in the initial 250 cases and subsequent 250 cases of RALP performed by a single surgeon in Taiwan, China.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

From December 2005 to December 2012, 515 consecutive patients with clinically localized prostate cancer received RARP performed by a single surgeon (YCO) at Taichung Veterans General Hospital. Fifteen cases were excluded from this study because the patients received pre-operative androgen-deprivation therapy, leaving 500 patients enrolled in the study. Prospective data collection was approved by the internal Institutional Review Board, and retrospective cases were reviewed. Patients were classified into two groups: Group I, cases 1–250 (December 2006 to December 2010); Group II, cases 251–500 (January 2011 to December 2012). Clinical characteristics were recorded for both groups and included age, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists anesthetic/surgical risks class, prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels, biopsy percentage, biopsy Gleason score, and clinical stage (2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer, AJCC, stage). Preoperative risk was determined by D’Amico classification:11 low-risk patients had T1c or T2a PSA levels <10 ng ml–1 or a Gleason score <7; intermediate-risk patients had T2b PSA levels of 10–20 ng ml–1 or a Gleason score = 7; and high-risk patients were beyond stage T2c with PSA levels >20 ng ml–1 or a Gleason score of 8–10.

RALP technique

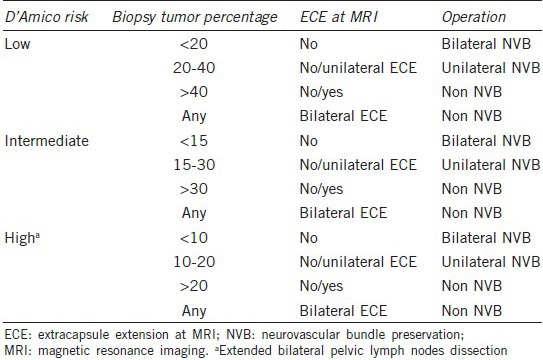

We performed the RALP procedure as described previously.9,10,12,13 A transperitoneal approach was made, using six trocar ports of a conventional four-arm da Vinci Robotic System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Surgical parameters were compared between the groups, including whether a bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) was performed, neurovascular bundle (NVB) preservation, console time, vesicourethral anastomosis time, estimated blood loss, transfusion rates, and complication rate. NVB preservation was assessed according to D’Amico risk classification, biopsy tumor percentage, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Table 1). Perioperative complications were recorded according to modifications of the Clavien system. Specimens were fixed, coated with Indian ink, and cut into systemic stepwise sections at 4 mm intervals.9,10,13 PSM was defined as the presence of tumor tissue on the inked surface of the specimen. Pathologic reports included the Gleason score, PSM, specimen volume, tumor volume, tumor percentage, and node status. BCR was defined as two consecutive PSA levels of >0.2 ng ml–1 after RALP. No adjuvant irradiation or hormonal therapy was given postoperatively for any patient, even those with lymph node metastasis. Patients were followed every 3 months for the 1st year, and thereafter at 6-month intervals. Follow-up time was set to the end day of BCR. Salvage irradiation or hormonal therapy was only implemented after BCR.

Table 1.

The principle of neurovascular bundle preservation

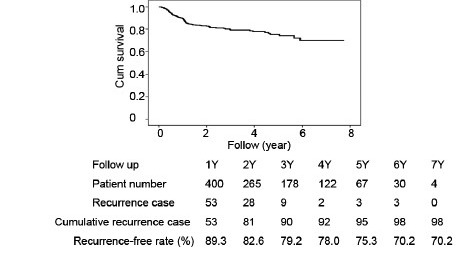

RESULTS

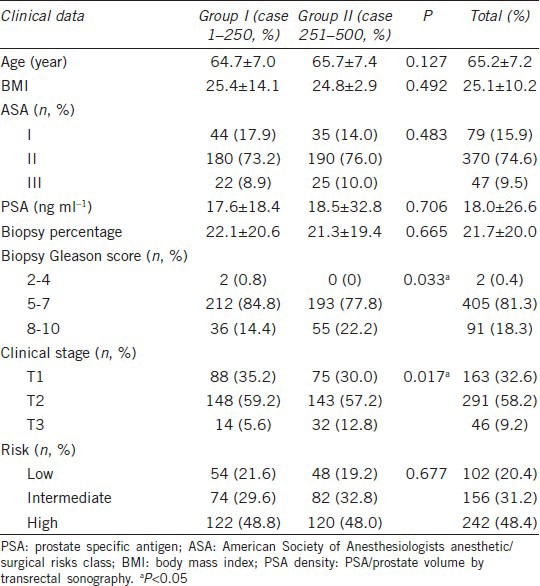

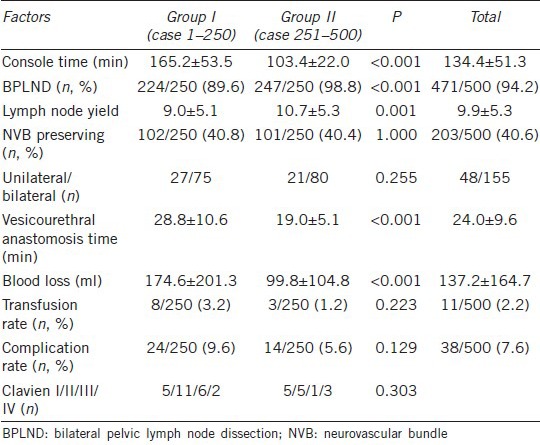

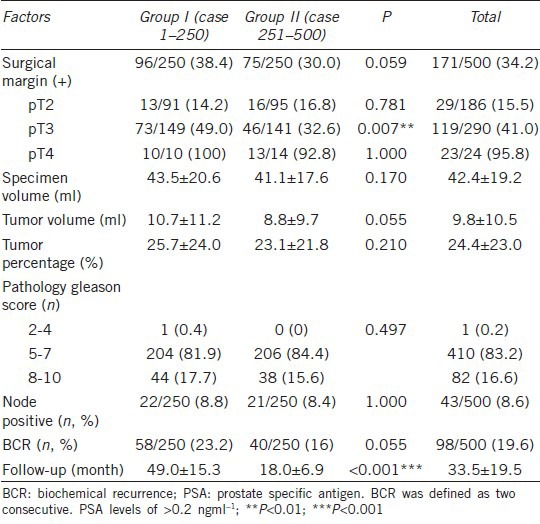

Table 2 shows a comparison of the preoperative clinical characteristics of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy by single surgeon. Patients in Group II had significantly more advanced prostate cancer than those in Group I (22.2% vs 14.2% of biopsy Gleason scores of 8–10, P = 0.033; 12.8% vs 5.6% with clinical stage T3, P = 0.017). Table 3 provides a comparison of surgical parameters and complication rates for RALP by a single surgeon. The console time and blood loss were decreased significantly from Group I to Group II (console time: 165.2 ± 53.5 min vs 103.4 ± 22.0 min, respectively, P < 0.001; blood loss: 174.6 ± 201.3 vs 99.8 ± 104.8 ml, respectively, P < 0.001). Blood transfusions were decreased from 3.2% (8/250) in Group I to 1.2% (3/250) in Group II, and the perioperative complication rate was reduced from 9.6% (24/250) in Group I to 5.6% (14/250) in Group II. Table 4 shows the PSM and BCR rates of RALP for a single surgeon. The PSM rate was decreased from 38.4% in Group I to 30.0% in Group 2 (P = 0.059). The PSM incidence among pT3 patients was decreased significantly 49.0% in Group I to 32.6% in Group 2 (P = 0.007). The BCR rate was 19.6% (98/500) at the mean 33.5-month follow-up. The rate of BCR-free survival was 89.3%, 79.2%, 75.3%, and 70.2% at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years, respectively (Figure 1). Among the 98 patients who developed BCR, 12 patients received observation only, and the others received salvage therapy, including 18 patients who received irradiation, 15 patients who received anti-androgen therapy, and 53 patients who received luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone agonist therapy.

Table 2.

Comparison of preoperative clinical characteristics of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in single surgeon

Table 3.

Comparison of operation parameters and complication rate of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in single surgeon

Table 4.

Positive surgical margin and BCR rates of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in single surgeon

Figure 1.

Biochemical recurrence-free survivals of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy of 500 cases in single surgeon

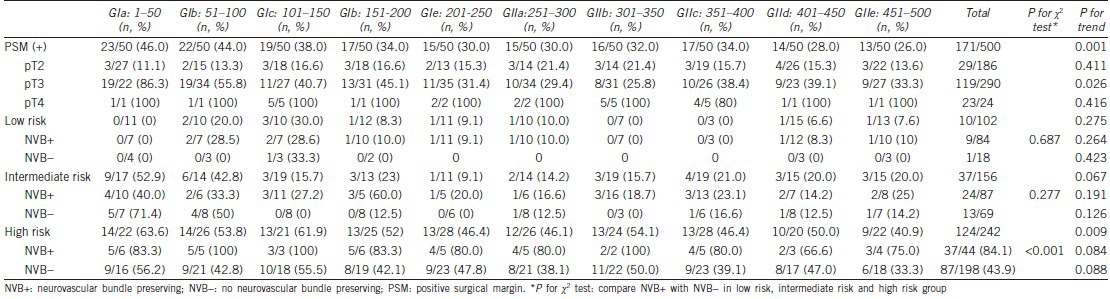

We analyzed the relationship between PSM with NVB preservation, D’Amico risk classification, and pathological stage among each group of 50 cases of RALP (Table 5). We identified a meaningful trend of decreasing PSM in each consecutive group of 50 cases (from 46.0% to 26.0%), including patients with pT3 cancer (from 86.3% to 33.3%) and high-risk patients (from 63.6% to 40.9%). NVB preservation was 82.3% (84/102) in low-risk patients (unilateral in 7, bilateral in 77), 55.7% (87/156) in intermediate-risk patients (unilateral in 18, bilateral in 69), and 18.2% (44/242) in high-risk patients (unilateral in 25, bilateral in 19). NVB preservation was significantly influenced by the PSM rate in high-risk patients (84.1% in NVB preservation patients vs 43.9% in non-NVB preservation patients, P < 0.01).

Table 5.

Relationship of positive surgical margin with NVB preserving, D'Amico classification risk classification and pathological stage between each 50 cases of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after RALP, based on the analysis of the first 500 surgeries performed by a single surgeon at a high volume center in Asia. The PSM rate was decreased from 38.4% in the initial 250 cases to 30.0% in the subsequent 250 cases. The PSM for patients at stage pT3 was decreased significantly from 49% to 32.6%. No large scale studies of RALP have been reported in an Asian country. Patients in our cohort had a mean PSA level of 18.02 ng ml–1 and were at clinical stage T1 (32.6%), T2 (58.2%), or T3 (9.2%) and pathological stage pT2 (37.2%), T3 (58.0%), or T4 (4.8%). The overall rates of PSM, pT2, T3, and T4 were 34.2%, 15.5%, 41.0%, and 95.8%, respectively. Postoperatively, no adjuvant therapy was given. The BCR-free survival rates were 79.2% (3 years), 75.3% (5 years), and 70.2% (7 years). The results reflect the real-world situation for prostate cancer in Asia. This can be compared with a study of 559 cases of LRP from Thailand: mean PSA, 17.6 ng/mL, clinical stages T1 (43.4%), T2 (35.1%), and T3 (21.5%), pathological stages pT2 (52.1%), T3 (39.9%), and T4 (2.9%). PSM rates overall and for pT2, T3, and T4 were 45.2%, 27.3%, 68.2%, and 76.9%, respectively.14 The 3-year BCR-free survival rate was 87.2%, excluding 135 patients (24.1%) due to immediate postoperative adjuvant hormonal therapy. Maybe the authors were presented with patients whose pathology reports indicated the possibility of high possibility of recurrence, causing them to give immediate postoperative adjuvant hormonal therapy. Even so, they did not implement immediate adjuvant radiation to PSM. Therefore, the real BCR-free survival rate will be lower than indicated in their report.

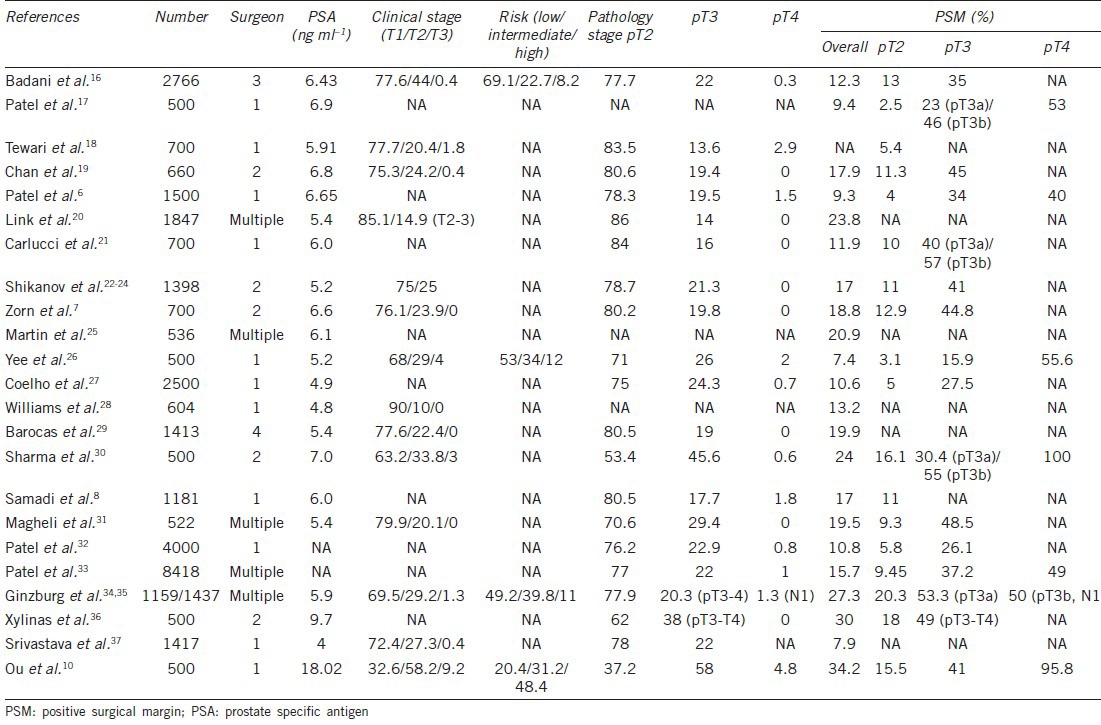

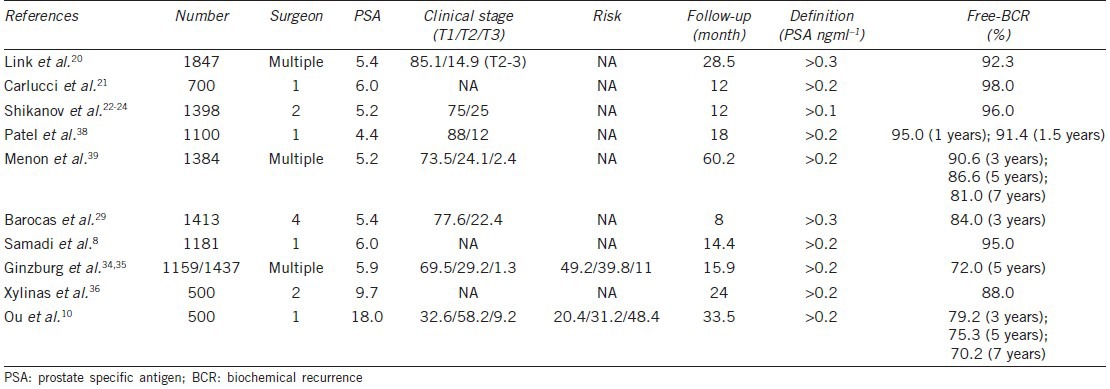

Oncologic outcome is the paramount endpoint for patients with prostate cancer receiving radical prostatectomy. The frequency of PSM in any series is influenced by surgical technique (procedure, neurovascular preservation, ability, and experience), tumor features (size, aggressiveness, extension), patient factors (BMI, prostate volume), and pathological analysis.15 We reviewed 22 studies of RALP with more than 500 cases reporting PSM (Table 6).7,8,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 These studies assessed patients with the following clinical characteristics: PSA, 4.4–9.7 ng ml–1; clinical stage T1, 63.2%–90.0%; cT3, 0%–3%; high-risk patients, and 8.2%–12.0%. There were from 53.4% to 87.6% of patients with T2, 12.4%–45.6% with pT3, and 0%–2.9% with pT4 pathology. The overall PSM rate ranged from 7.4% to 30.0%, 2.5%–16.1% for pT2, 15.9%–48.5% for pT3, 40%–100% for pT4 (Table 6). Our cohort had higher PSA levels (18.0 ng ml–1) than those from other studies and more advanced cT3-stage (9.2%) and high-risk (48.4%) patients. It is reasonable that the stage of pathology revealed 37.2% at pT2, 58% at pT3, and 4.8% at pT4, and it is not surprising that the overall incidence of PSM (34.2%) for this study was higher than for other studies (7.4%–30.0%). Our PSM rate for pT2 (15.5%), pT3 (41.0%), and pT4 (95.8%) patients was within the range of those from other studies around the world (Table 6). We reviewed nine studies of RARP for which more than 500 cases reported BCR (Table 7).7,20,21,22,23,24,29,34,35,36,38,39 The clinical characteristics of these cohorts included PSA 4.4–9.7 ng ml–1, 69.5%–88.0% of clinical stage T1, 12.0%–29.2% of T2, 0%–2.4% of T3, and about 11% high-risk patients. The mean follow-up period was from 8.0 to 60.2 months. The portion of patients free of BCR ranged from 95.0% to 98.0% at 1 year, 84.0%–90.6% at 3 years, 72.0%–86.6% at 5 years, and was 81.0% at 7 years (Table 7). Patients in our cohort had higher PSA levels and higher numbers of advanced-stage and high-risk patient. Patients were followed up for an average of 33.5 months, and the rate of patients free of BCR (80.4%) within the range of other studies around the world (Table 7).

Table 6.

Positive surgical margin of robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in world series>500 cases

Table 7.

Free of biochemical recurrence of robotic-assisted laparoscopy radical prostatectomy in world series >500 cases

The learning curve for prostate cancer surgery, as measured by cancer recurrence, plateaus after approximately 250 open radical prostatectomy operations.1 LRP may be inherently more difficult to learn and to master. The 5-year risk of BCR was shown to decrease from 17% to 16% or 9% for patients treated by surgeons with 10, 250, or 750 prior laparoscopic procedures, respectively (risk difference between 10 and 750 procedures = 8.0%, 95% CI: 4.4%–12.0%).2 The learning curve for LRP was slower than the previously reported learning curve for open surgery, requiring about 750 prior procedures to achieve plateau.2 Savage and Vickers40 reported low annual caseloads for US surgeons conducting radical prostatectomy. More than 25% of surgeons performed only one radical prostatectomy in 2005, and about 80% of surgeons perform fewer than 10 procedures/year.40 These investigators concluded many patients were treated by surgeons with extremely low annual caseloads, with poorer outcomes a likely result.40 Many studies have documented a trend toward RALP being the treatment of choice for localized prostate cancer.40 In 2006, RALP constituted only 10% of the total number of radical prostatectomies performed by American urologists; however, the proportion has increased to more than 65% in 2008 and 85% in 2009.41,42 Furthermore, the reported trend in radical prostatectomy was centralization at high-volume centers equipped with robotics.43 Reviews of high-volume centers reported excellent outcome (53%–91%) for the “trifecta” (positive margin rate, continence, and sexual potency).11,38 Details of the learning curve for cancer control have seldom been discussed. Our data show that after the initial experience with 250 cases of RALP, the PSM of pT3 was decreased significantly from 49.0% to 32.9% for the subsequent 250 cases. There was also a trend in the surgical learning curve for decreasing PSM with consecutive 50-case groups, including pT3, and high-risk cases. Klein et al.44 also reported cancer control after radical prostatectomy improves with increasing surgeon experience, irrespective of patient risk. The absolute risk differences for patients from different preoperative risk groups receiving treatment from a surgeon with 10 versus 250 prior radical prostatectomies were (95% CI): low-risk, 6.6% (3.4%–10.3%); medium-risk, 12.0% (6.9%–18.2%); and high-risk, 9.7% (1.2%–18.2%).44 Patel et al.6 reported on 1500 cases of RALP, for which the relationship between PSM rate and case-count was: 12.2% (1–300 cases), 6.6% (301–600 cases), 13.6% (601–900 cases), 11.0% (901–1200 cases), and 1.8% (1201–1500 cases). The 5-year recurrence-free probability for patients with organ-confined disease approached 100% for the most experienced surgeons.45 Conversely, the learning curve for surgery in patients with locally advanced disease flattens at approximately 70%, suggesting that about a third of these patients cannot be cured by surgery alone.45 For RALP, there is still room for improving cancer control for high-risk groups and those with locally advanced prostate cancer.

Our data revealed that NVB preservation was significantly influenced by PSM in high-risk patients (84.1% in NVB preservation group vs. 43.9% in non-NVB preservation group, P < 0.01). Our results support the view that NVB preservation during RALP is not suggested for high-risk prostate cancer due to the increased incidence of PSM. Ginzburg et al.35 reported that nerve-sparing surgical status (bilateral, unilateral, or nonnerve sparing) during RALP did not significantly affect the incidence of PSM (P = 0.672). This cohort included low mean PSA levels (5.9 ng ml–1) and low percentages of T3 (1.3%) and high risk (11%) patients. Our cohort had poor prognostic factors, including high mean PSA level and 9.2% of cT3 and high-risk (48.4%) patients. Most experienced robotic surgeons suggest a risk-stratified grade of nerve-sparing technique during RALP.37 Tewari et al.18 advised nonnerve sparing in risk grade 4 (PSA level >20 ng ml–1, clinical stage T3, Gleason score 8–10, confirmed extra-prostate extension on MRI) with 17.4% of PSM. Intraoperative frozen section (FS) of the prostate was performed by von Bodman et al.46 to decrease the PSM rate while retaining the nerve-sparing procedure during radical prostatectomy. In their study of 236 patients (176 RPP, 60 RALP), the overall final PSM rate was 3.0% (7/236). The intraoperative PSM rate dropped from 22% to 3%, including a false negative FS rate of 1.6%. In 14.8% of patients (35/236), the initial nerve-sparing plan was intraoperatively changed to resect NVB due to positive FS. Nerve-sparing was performed in 96.5% of pT2, 85.4% of pT3a, and 81.8% of pT3b patients.46

In this study with a mean follow-up of only 33.5 months, the 3-year and 5-year BCR-free survival rate was acceptable. This was achieved because we established a dedicated robotic team and learned from experts, which helps to shorten the learning curve for RALP.12 In our cohort, 40.0% of all patients (203/500) received NVB preservation, whereas only 18.2% (44/242) of high-risk patients received NVB preservation. Another explanation is that we performed BPLND in the majority of cases (94.2%), including pre-prostate fat pad dissection for all patients and extended BPLND for high-risk patients.10,47

The limitation of this study was the short mean follow-up period of 33.5 months. A mean follow-up time of more than 5 or 10 years is needed to define long-term BCR-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival. These results do not apply to other hospitals in Asia. Our experience represents a high-caseload surgeon (YCO), who performed 82.9% (194/234) of RALP procedures at Taichung Veterans General Hospital and 38.3% (194/507) of RALP before 2009 in Taiwan, China.48 This so-called “halo effect” phenomenon in Taiwan, China,48 is in line with centralization to high-volume surgery centers as reported in the USA.43

The strengths of this study are the prospectively collected database and its reliance on the experience of a single surgeon. These combine to reduce the bias associated with a retrospective review and combining results from different surgeons with dissimilar learning curves. Furthermore, our study represents the real world of patient characteristics, with a higher proportion of advanced-disease and high-risk patients receiving RALP in Asian countries. Large scale or government-sponsored PSA screening is not performed in Asia, resulting in a surgical population that is about 50% high-risk patients.

CONCLUSIONS

This study with a comparison of the incidence of PSM in pT3 prostate cancer in the initial 250 cases of RARP versus the subsequent 250 cases revealed a significant decrease from 49.0% to 32.9%. There was a trend in the surgical learning curve for decreased rate of PSM with each consecutive group of 50 cases, including pT3, and high-risk patients. The PSM rate was reduced from 86.3% for the first 50 cases (cases 1–50) to 33.3% for the last 50 cases (cases 451–500). NVB preservation during RALP is not suggested for high-risk prostate cancer patients, due to increasing PSM. The 5-year and 7-year BCR-free survival rates were 75.3% and 70.2%, respectively. Long-term follow-up will be necessary to clarify cancer-specific survival rates.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YCO is the principal investigator, conceived to the concept and design of the study, data interpretation, and drafted and revised this manuscript. CKY contributed to the concept and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. KSC was responsible for the concept of the study, data acquisition, statistical analysis, and critically revising manuscript. JW and SWH carried out data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. MCT contributed to data acquisition, administrative support, and critically revising manuscript for important intellectual content. AKT and VRP responsible for technical and teaching video support and consultation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the staff of urology and operation team (including nurses and anesthetists) of Taichung Veterans General Hospital for their operation assistance and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, et al. The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1171–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vickers AJ, Savage CJ, Hruza M, Tuerk I, Koenig P, et al. The surgical learning curve for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:475–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrell SD, Smith JA., Jr Robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: what is the learning curve? Urology. 2005;66(Suppl):105–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atug F, Castle EP, Srivastav SK, Burgess SV, Thomas R, et al. Positive surgical margins in robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: impact of learning curve on oncologic outcomes. Eur Urol. 2006;49:866–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahlering TE, Eichel L, Edwards RA, Lee DI, Skarecky DW. Robotic radical prostatectomy: a technique to reduce pT2 positive margins. Urology. 2004;64:1224–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel VR, Palmer KJ, Coughlin G, Samavedi S. Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: perioperative outcomes of 1500 cases. J Endourol. 2008;22:2299–305. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.9711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorn KC, Wille MA, Thong AE, Katz MH, Shikanov SA, et al. Continued improvement of perioperative, pathological and continence outcomes during 700 robot-assisted radical prostatectomies. Can J Urol. 2009;16:4742–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samadi DB, Muntner P, Nabizada-Pace F, Brajtbord JS, Carlucci J, et al. Improvements in robot-assisted prostatectomy: the effect of surgeon experience and technical changes on oncologic and functional outcomes. J Endourol. 2010;24:1105–10. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou YC, Yang CR, Wang J, Cheng CL, Patel VR. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: learning curve of first 100 cases. Int J Urol. 2010;17:635–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ou YC, Yang CK, Wang J, Hung SW, Cheng CL, et al. The trifecta outcome in 300 consecutive cases of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy according to D’ Amico risk criteria. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou YC, Yang CR, Wang J, Yang CK, Cheng CL, et al. The learning curve for reducing complications of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy by a single surgeon. BJU Int. 2011;108:420–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou YC, Hung SW, Wang J, Yang CK, Cheng CL, et al. Retro-apical transection of the urethra during robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in an Asian population. BJU Int. 2012;110:E57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wattayang P, Nualyong C, Leewansangtong S, Srinualnad S, Taweemonkongsap T, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: oncological and functional outcomes of 559 cases in Siriraj Hospital, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:941–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch MO. Positive margins in urological oncology. J Urol. 2007;178:2249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badani KK, Kaul S, Menon M. Evolution of robotic radical prostatectomy: assessment after 2766 procedures. Cancer. 2007;110:1951–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel VR, Thaly R, Shah K. Robotic radical prostatectomy: outcomes of 500 cases. BJU Int. 2007;99:1109–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tewari A, Jhaveri J, Rao S, Yadav R, Bartsch G, et al. Total reconstruction of the vesico-urethral junction. BJU Int. 2008;101:871–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan RC, Barocas DA, Chang SS, Herrell SD, Clark PE, et al. Effect of a large prostate gland on open and robotically assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2008;101:1140–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link BA, Nelson R, Josephson DY, Yoshida JS, Crocitto LE, et al. The impact of prostate gland weight in robot assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;180:928–32. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlucci JR, Nabizada-Pace F, Samadi DB. Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: technique and outcomes of 700 cases. Int J Biomed Sci. 2009;5:201–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikanov SA, Zorn KC, Zagaja GP, Shalhav AL. Trifecta outcomes after robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Urology. 2009;74:619–23. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiltz AL, Shikanov S, Eggener SE, Katz MH, Thong AE, et al. Robotic radical prostatectomy in overweight and obese patients: oncological and validated-functional outcomes. Urology. 2009;73:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.08.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shikanov S, Song J, Royce C, Al-Ahmadie H, Zorn K, et al. Length of positive surgical margin after radical prostatectomy as a predictor of biochemical recurrence. J Urol. 2009;182:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin GL, Nunez RN, Humphreys MD, Martin AD, Ferrigni RG, et al. Interval from prostate biopsy to robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: effects on perioperative outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;104:1734–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yee DS, Narula N, Amin MB, Skarecky DW, Ahlering TE. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: current evaluation of surgical margins in clinically low-, intermediate-, and high-risk prostate cancer. J Endourol. 2009;23:146–5. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coelho RF, Palmer KJ, Rocco B, Moniz RR, Chauhan S, et al. Early complication rates in a single-surgeon series of 2500 robotic-assisted radical prostatectomies: report applying a standardized grading system. Eur Urol. 2010;57:945–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams SB, Chen MH, D’Amico AV, Weinberg AC, Kacker R, et al. Radical retropubic prostatectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: likelihood of positive surgical margin (s) Urology. 2010;76:1097–101. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barocas DA, Salem S, Kordan Y, Herrell SD, Chang SS, et al. Robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus radical retropubic prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: comparison of short-term biochemical recurrence-free survival. J Urol. 2010;183:990–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma NL, Papadopoulos A, Lee D, McLoughlin J, Vowler SL, et al. First 500 cases of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy from a single UK centre: learning curves of two surgeons. BJU Int. 2011;108:739–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magheli A, Gonzalgo ML, Su LM, Guzzo TJ, Netto G, et al. Impact of surgical technique (open vs laparoscopic vs robotic-assisted) on pathological and biochemical outcomes following radical prostatectomy: an analysis using propensity score matching. BJU Int. 2011;107:1956–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel VR, Abdul-Muhsin HM, Schatloff O, Coelho RF, Valero R, et al. Critical review of ‘pentafecta’ outcomes after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy in high-volume centres. BJU Int. 2011;108:1007–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel VR, Coelho RF, Rocco B, Orvieto M, Sivaraman A, et al. Positive surgical margins after robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: a multi-institutional study. J Urol. 2011;186:511–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ginzburg S, Hu F, Staff I, Tortora J, Champagne A, et al. Does prior abdominal surgery influence outcomes or complications of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy? Urology. 2010;76:1125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginzburg S, Nevers T, Staff I, Tortora J, Champagne A, et al. Prostate cancer biochemical recurrence rates after robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. JSLS. 2012;16:443–50. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13462882736538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xylinas E, Durand X, Ploussard G, Campeggi A, Allory Y, et al. Evaluation of combined oncologic and functional outcomes after robotic-assisted laparoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy: trifecta rate of achieving continence, potency and cancer control. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava A, Chopra S, Pham A, Sooriakumaran P, Durand M, et al. Effect of a risk-stratified grade of nerve-sparing technique on early return of continence after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2013;63:438–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel VR, Coelho RF, Chauhan S, Orvieto MA, Palmer KJ, et al. Continence, potency and oncological outcomes after robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: early trifecta results of a high-volume surgeon. BJU Int. 2010;106:696–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menon M, Bhandari M, Gupta N, Lane Z, Peabody JO, et al. Biochemical recurrence following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: analysis of 1384 patients with a median 5-year follow-up. Eur Urol. 2010;58:838–46. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savage CJ, Vickers AJ. Low annual caseloads of United States surgeons conducting radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2009;182:2677–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dasgupta P, Kirby RS. The current status of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Asian J Androl. 2009;11:90–3. doi: 10.1038/aja.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz BF. Training requirements and credentialing for laparoscopic and robotic surgery – what are our responsibilities? J Urol. 2009;182:828–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stitzenberg KB, Wong YN, Nielsen ME, Egleston BL, Uzzo RG. Trends in radical prostatectomy: centralization, robotics, and access to urologic cancer care. Cancer. 2012;118:54–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein EA, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Kattan MW, et al. Surgeon experience is strongly associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy for all preoperative risk categories. J Urol. 2008;179:2212–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Gonen M, Cronin AM, Eastham JA, et al. Effects of pathologic stage on the learning curve for radical prostatectomy: evidence that recurrence in organ-confined cancer is largely related to inadequate surgical technique. Eur Urol. 2008;53:960–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Bodman C, Brock M, Roghmann F, Byers A, Löppenberg B, et al. Intraoperative frozen section of the prostate decreases positive margin rate while ensuring nerve sparing procedure during radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2013;190:515–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim IY, Modi PK, Sadimin E, Ha YS, Kim JH, et al. Detailed analysis of patients with metastasis to the prostatic anterior fat pad lymph nodes: a multi-institutional study. J Urol. 2013;190:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu CL, Li CC, Yang CR, Yang CK, Wang SS, et al. Trends in treatment for localized prostate cancer after emergence of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:155–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]