Abstract

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methodology is described for the determination of S-(N,N-diethylcarbamoyl)glutathione (carbamathione) in human plasma samples. Sample preparation consisted of a straightforward perchloric acid medicated protein precipitation, with the resulting supernatant containing the carbamathione (recovery ∼98%). For optimized chromatography/mass spec detection a carbamathione analog, S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione, was synthesized and used as the internal standard. Carbamathione was found to be stable over the pH 1-8 region over the timeframe necessary for the various operations of the analytical method. Separation was accomplished via reversed-phase gradient elution chromatography with analyte elution and re-equilibration accomplished within 8 minutes. Calibration was established and validated over the concentration range of 0.5-50 nM, which is adequate to support clinical investigations. Intra- and inter-day accuracy and precision determined and found to be < 4% and < 10%, respectively. The methodology was utilized to demonstrate the carbamathione plasma-time profile of a human volunteer dosed with disulfiram (250 mg/d). Interestingly, an unknown but apparently related metabolite was observed with each human plasma sample analyzed.

Keywords: LC-MS/MS, Carbamathione, Disulfuram, Glutathione conjugates

1. Introduction

Disulfiram has been used for the treatment of alcohol dependence since its accidental discovery approximately 60 years ago [1]. The pharmacological basis and rationale for the use of disulfiram as a deterrent treatment for alcohol dependence is its inhibition of liver low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2). The inhibition of ALDH2 results in an increase in acetaldehyde which is believed to be responsible for the adverse effects known as the disulfiram-ethanol reaction. Disulfiram is a pro-drug that requires bioactivation to an active metabolite which is responsible for the inhibition of ALDH2 [2, 3, 4]. The metabolite responsible for the inhibition of ALDH2 has been identified as DETC-MeSO [5] and the cytochrome P450 enzymes required in this bioactivation process has been delineated [6, 7]. DETC-MeSO is oxidized to S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulfone (DETC-MeSO2) [8] and subsequently to S-(N,N-diethylcarbamoyl) glutathione (carbamathione) [9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Metabolites of disulfiram referred to in this work.

Carbamathione is a partial NMDA glutamate antagonist [9] but does not inhibit liver ALDH2 [10]. The clinical significance of carbamathione and its possible neurochemical activity [9] was not considered until studies showed that disulfiram was a promising therapeutic agent for treating cocaine dependence [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Although the mechanism of action of disulfiram's effectiveness in cocaine dependence is unclear, a working hypothesis has emerged that carbamathione may be the responsible metabolite because of its NMDA glutamate receptor activity [9]. Early metabolite distribution studies with radio labelled 35S [16, 17] suggested a possible disulfiram metabolite in rat brain would no longer carry a disulfiram derived sulphur but rather a metabolite with only a N,N-diethylcarbamoyl moiety. In rat studies carbamathione has since been found in rat urine, bile [18], plasma and brain [19]. While carbamathione has been detected in a variety of rat fluids, the suggestion that carbamathione may have a neurological action in humans must be supported by detection in humans.

In a previous report [19], methodology was described for the determination of carbamathione present in rat brain and plasma where sampling and sample preparation was accomplished by microdialysis. The samples further subjected to reversed-phase gradient elution liquid chromatography (LC) separation followed by detection and quantification by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). While allowing for determination at the 1 nM level, the combination of internal standard (IS) retention and chromatographic re-equilibration resulted in a sample throughput time of 50 minutes.

The goal of the present investigation was the development of methodology for the determination of carbamathione in human plasma samples suitable for support of human clinical investigations with improved sample throughput. Issues to be addressed include plasma sample preparation and the identification of an internal standard that is optimized with respect to the LC retention window and provides for sensitive and selective MS detection. While plasma sample preparation proved to be straightforward using acid mediated protein precipitation, the identification of an internal standard meeting the previously noted criteria involved the synthesis and evaluation of several glutathione analogs in order to meet the desired criteria. Ultimately the developed methodology described herein was applied to human plasma samples obtained from disulfiram-dosed healthy volunteers, and to our knowledge, appears to be the first report of the presence of carbamathione as a disulfiram metabolite in humans.

2. Experimental

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Carbamathione was synthesized using methods previously developed [18] and obtained from Kaul et al. [19]. S-n-butylglutathione, tris hydrochloride, ammonium bicarbonate, di-i-propylcarbamoylchloride, and propyl-, butyl- and pentylisocyanate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ammonium acetate, sodium phosphate, formic acid, perchloric acid (70%) and HPLC grade methanol were obtained from Fisher (Fairlawn, NJ, USA). Nanopure water was prepared by a Water Pro Plus purification system (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA). Blank pooled human plasma was purchased from Innovative Research (Novi, MI, USA).

2.2 Synthesis of internal standard candidates

2.2.1 General procedure for S(N-alkylcarbamoyl)glutathione derivatives

Carbamathione analogs were synthesized by reacting propyl-, butyl- or pentyl isocyanate with glutathione according to the method of Han et al. [20]. The structures of the products obtained were confirmed by 1H NMR and mass spectrometry.

2.2.1.1 S-(N-n-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione

Exact mass determination of [M+H]+ C14H25N4O7S was 393.1451± 0.0015 (n = 3) which deviated by 1.8 ppm from the expected mass. The proton NMR chemical shifts were δ 0.82 t 3H (CH3CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.41 h 2H (CH3CH2*CH2NH–), δ 1.91 q 2H (Glu-β,β′), δ 2.3 m 2H (Glu-γ,γ′), δ 3.05 q 2H (CH3CH2CH2*NH–), δ 3.32 m 2H (Cys-β, Glu-α), δ 3.68 d 2H (Gly-α,α′), δ 4.34 t, 1H (Cys-α). (* indicates specific protons)

2.2.1.2 S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione

Exact mass determination of [M+H]+ C15H27N4O7S was 407.1590± 0.0008 (n = 3) which deviated by -2.5 ppm from the expected mass. The proton NMR chemical shifts were δ 0.85 t 3H (CH3CH2CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.25 h 2H (CH3CH2*CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.38 q 2H (CH3CH2CH2*CH2NH–) δ 1.91 m 2H (Glu-β,β′), δ 2.29 q 2H (Glu-γ,γ′), δ 3.08 m 2H (CH3CH2CH2CH2*NH–), δ 3.32 m 2H (Cys-β, Glu-α), δ 3.68 dd 2H (Gly-α,α′), δ 4.33 dt, 1H (Cys-α). (* indicates specific protons)

2.2.1.3 S-(N-n-pentylcarbamoyl)glutathione

Exact mass determination of [M+H]+ C16H29N4O7S was 421.1764± 0.0010 (n = 3) which deviated by 1.7 ppm from the expected mass. The NMR chemical shifts for the proton NMR were δ 0.85 t 3H (CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.22 h 2H (CH3CH2CH2*CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.26 m 2H (CH3CH2*CH2CH2CH2NH–), δ 1.39 q 2H (CH3CH2CH2CH2*CH2NH–) δ 1.91 m 2H (Glu-β,β′), δ 2.3 q 2H (Glu-γ,γ′), δ 3.07 m 2H (CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2*NH–), δ 3.32 m 2H (Cys-β, Glu-α), δ 3.68 dd 2H (Gly-α,α′), δ 4.34 dt, 1H (Cys-α). (* indicates specific protons)

2.2.1.4S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione

A solution of diisopropylcarbamoylchloride (1.2 mmol in 7 ml pyridine) was added to a solution of glutathione (0.6 mmol in 3 ml water) and stirred over night at room temperature. The resulting mixture was evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in 6 ml water. Care must be taken that the reaction mixture is not heated excessively (30 °C max) during reaction or solvent evaporation as excessive heating results in an oily orange byproduct, which is difficult to remove. The crude product was subjected to C18 semi- preparatory HPLC (70 % H2O, 30% methanol and 0.1% formic acid) and dried in a lyophilizer, resulting in a white powder. The structure was confirmed by 1H NMR and mass spectrometry. Exact mass determination of [M+H]+ C17H31N4O7S was 435.1901± 0.0006 (n = 3) which was -2.8 ppm from the expected mass. The proton NMR chemical shifts were δ 1.21 d 12H ((CH3)2CH)2N–), δ 1.91 q 2H (Glu-β,β′), δ 2.29 m 2H (Glu-γ,γ′), δ 3.33 m 5H (((CH3)2CH*)2N-, Cys-β, Glu-α), δ 3.69 d 2H (Gly-α,α′), δ 4.35 t, 1H (Cys-α). (* indicates specific protons)

2.3 Methods

2.3.1 LC method for MS detection

Solvents were delivered by a Waters Acquity UPLC system. Chromatographic separation was performed using a Phenomenex Kinetex column ( phase C18; diameter, 2.1 × 50 mm; particles size, 1.7 μm; pore size, 100 Å), which was protected by a Phenomenex KrudKatcher Ultra filter (0.5 μm pores, 316 stainless steel ) followed by a Waters Vanguard C8 pre-column. Chromatographic solvents consisted of A: 99% H2O, 1% methanol and 0.1% formic acid and B: 1% H2O, 99% methanol and 0.1% formic acid delivered at a flow rate of 400 μl/min. The sample was injected (50 μL volume) onto a column that was pre-equilibrated at 5% B. After 0.2 min a linear gradient of 11% B/min for 4 minutes was implemented. The column was then washed with 80% B for 2 minutes and subsequently re-equilibrated at 5% B for 1.5 minutes, resulting in a total run-time of 8 minutes. For the first two minutes, chromatographic effluent is diverted to waste, preventing salts and polar endogenous compounds from entering the mass spectrometer.

2.3.2 LC method for UV detection

The HPLC system consisted of two Shimadzu LC6A pumps and a Shimadzu SIL-6B auto injector (50 μl injection utilized) controlled by a Shimadzu SCL-6B system controller. Detection was accomplished using a Kratos UV/Vis chromatographic detector set at 215 nm with TurboChrom V4 used for data collection. Chromatographic separation was conducted using a Phenomenex Inertsil ODS-3 column (150 × 4.6mm, 5μ particles, 100 Å) protected with a Supelcosil LC-8 guard column (2 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm particles). An isocratic solvent program consisting of 70% A (95% H2O, 5% methanol and 0.1% formic acid) and 30% B (5% H2O, 95% methanol and 0.1% formic acid) with a flow rate of 1ml/min, was utilized for the chromatography.

2.3.3 Mass spectrometry parameters

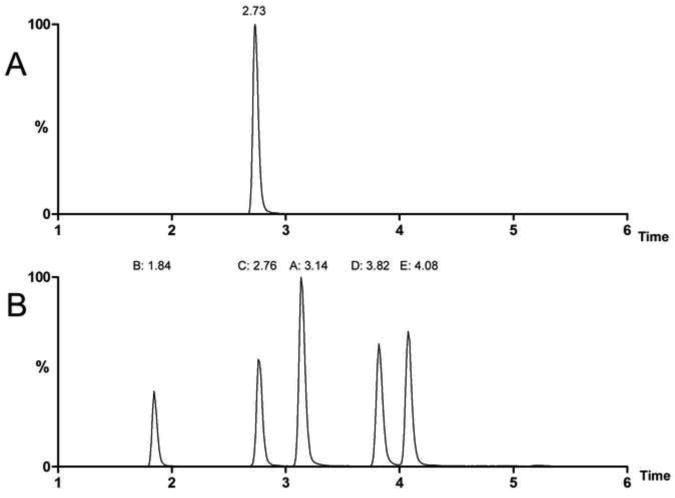

Mass spectrometry was performed on a Quattro Ultima “triple” quadrupole instrument (Micromass Ltd., Manchester UK). The mass spectrometer was run in positive ion mode using an ESI ionization source. The mass spectrometer source block was set at 100 °C and the desolvation gas temperature was set at 300 °C. Argon collision gas was set to attenuate the beam by 10-20% (10−3 mbar). Quadrupoles 1 and 3 were tuned to a resolution of 0.9 amu FWHH. Collision energy and cone voltage settings are optimized for each compound. Data processing was performed using MassLynx 4.1 and Graphpad Prism 5. Fragmentation patterns of S-n-butyl-glutathione, S-(N-n-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione, S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)-glutathione, S-(N-n-pentylcarbamoyl)-glutathione, S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione and carbamathione and were determined by infusing an aqueous solution of the respective compound at 400 μl/min 30% solvent B (HPLC-MS method) for source optimization. Product ion scans were acquired at varying collision energies, 10-45 V. One MRM transition unique to the substance was chosen for each compound and the collision energies optimized. The most abundant MRM transitions were chosen for the secondary carbamoyl substances and S-n-alkyl conjugates. However, for the tertiary carbamoyl substances a carbamoyl moiety related fragment was selected as most suitable reporter transition (Figure 2). The mass transitions and optimum settings for all compounds are summarized in Table 1. Subsequently a mixture of all five internal standard candidates (100 nM solution of each) was run on the HPLC-MS system to determine relative retention times with respect to carbamathione (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

HPLC SRM of a plasma sample obtained from a female volunteer one hour after oral administration of disulfiram, 250 mg. (see Human Studies).

Table 1.

Parent ion and SRM fragment for quantitation and their optimum cone voltage and collision energy settings.

| Parent | Collision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Ion | Fragment | Cone Voltage | Energy (V) | |

| A | S-butylglutathione | 364.0 | 218.0 | 35.0 | 15.0 |

| B | S-(N-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione | 393.0 | 264.0 | 35.0 | 14.0 |

| C | S-(N-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione | 407.0 | 278.0 | 35.0 | 14.0 |

| D | S-(N-pentylcarbamoyl)glutathione | 421.0 | 292.0 | 35.0 | 14.0 |

| E | diisopropylcarbamathione | 435.0 | 128.0 | 35.0 | 30.0 |

| F | Carbamathione | 407.1 | 100.0 | 35.0 | 30.0 |

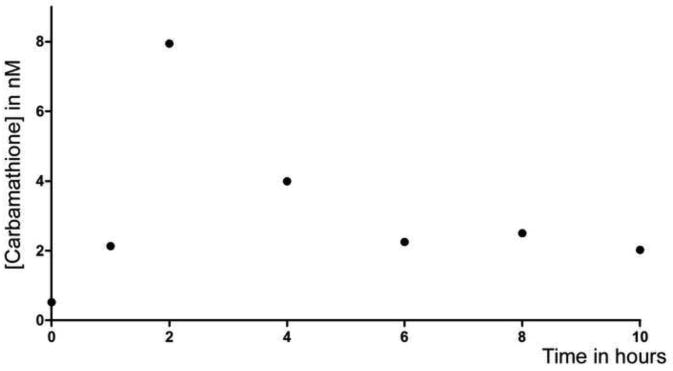

Figure 3. Plasma profile obtained from a female volunteer after oral administration of 250 mg of disulfiram. (see Human Studies).

2.3.4 Sample pretreatment

Plasma, 100 μl in an Eppendorf tube, was spiked with 10 μl of 100 nM S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione (internal standard) and for calibration curves, 10 μl of a carbamathione solution. Water, 45 μl, was then added and the mixture vortexed for 5 seconds. In the case of blank or patient samples, 55 μl water was added instead of 45 μl to compensate for the volume. Proteins were precipitated by the addition of 35 μl perchloric acid and the mixture vortexed for 5 seconds and then placed on ice for 5 minutes. The precipitated sample was subsequently centrifuged for 5 minutes at 11,000 times gravity (13000 rpm at 60 mm radius). The supernatant was recovered and transferred to an autosampler vial for subsequent determination.

2.3.5 Stability

Carbamathione plasma stability was tested in pooled human plasma. Samples (n=5) enriched with 150 μM carbamathione were allowed to incubate at room temperature for 2, 4, 6 and 24 hours prior to acid mediated precipitation. Analyte stability in the plasma extract was assayed in the fashion, but substituting plasma for the acid plasma extract. A limited freeze-thaw stability experiment was performed by analyzing carbamathione enriched plasma samples (n=5) at day 1, 3 and 7 of a seven day period. Carbamathione stability was checked against a five point calibration curve ranging from 50 to 250 μM carbamathione in plasma.

2.4 Validation

The sample pretreatment method was applied (n=5) to five spiked plasma concentrations of 50.0, 10.0, 5.0, 1.0, and 0.5 nM and the samples analyzed according to the described methodology. This experiment was repeated for 4 consecutive days to determine intra and inter-day stability of the method. Data was processed for linearity, precision, accuracy and to determine the limit of quantification. An infusion of carbamathione was utilized to obtain a qualitative assessment of ionization suppression caused by the human plasma matrix. An infusion pump was used to deliver a constant amount of carbamathione post-column into the LC stream entering the mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer was set in SRM mode to monitor the analyte signal stability and a blank plasma sample was injected onto the column. Carbamathione stability was assessed at various pH's and at elevated temperature. Solutions of carbamathione (100 μM) were prepared in five 100 mM buffer solutions of perchloric acid (pH 1), formic acid (pH 2.5), acetate (pH 4), tris (pH 6) and phosphate (pH 8). Sample vials were kept at 50 °C and samples taken every 24 hours for 5 consecutive days to determine stability employing the HPLC-UV method. Samples were checked against a control sample that was stored at −20 °C and thawed immediately prior to analysis.

2.5 Human studies

A healthy 52-year-old female Caucasian volunteer with no alcohol or other substance use disorders was recruited. Voluntary, written, informed consent was obtained, and approval obtained from the University of California at San Francisco Committee on Human Research. The patient volunteer weighed 69 kg and was 160 cm in height. Disulfiram 250 mg/d was administered with staff observation for 3 days. On the fourth day, after an eight hour overnight fast, an antecubital venipuncture was undertaken and 7 ml of blood was drawn into a heparinized tube to obtain trough disulfiram concentration in the plasma. A urine sample was also collected prior to disulfiram dosing to test for recent use of any illicit substances. A 250 mg dose of disulfiram was then administered and blood samples drawn at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 hours after disulfiram dosing. Each blood sample was immediately centrifuged and the plasma separated and frozen at −70 °C until the time of determination of carbamathione.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Chromatography

As noted previously, human plasma assay methodology for carbamathione must possess the necessary sensitivity and selectivity to support continued clinical investigation, but from an analytical perspective, should also be robust and enable high sample throughput. In order to achieve high efficiency rapid separations one frequently resorts to the use of high linear velocities (> 2 mm/s), small particles (< 3μm) or a combination of these parameters, which can result in the need for much higher operating pressures as compared to those available to many common LC systems currently in use. An alternative approach is the use of solid core particles featuring a porous shell that results in efficient kinetic performance without the need for substantially higher operating pressures. Based on these considerations chromatographic method development was based on the use of a reverse-phase Phenomenex Kinetex column (1.7 μm porous shell particles), which reduces diffusion distance in the retention process and thus mimics the chromatographic performance of smaller particles (e.g. 1 μm particles) without the associated increase in backpressure needed to achieve similar linear velocities with the smaller diameter particles.

Other aspects addressed include the development of an efficient chromatographic gradient elution program. For high sensitivity bioanalysis, one is often interested in using a relatively large injection volume with respect to the dimensions of the chromatographic column in order to minimize dilution. To this end, when possible it is desirable to use an initially weak mobile phase composition with respect to the analyte and/or injection solvent composition to allow for larger volume injections, thus providing for the achievement of trace enrichment, which translates into the potential to achieve high sensitivity detection.

With these criteria in mind, the gradient profile implemented consisted of an analyte focusing step (initial mobile phase composition was ∼5% MeOH), a relatively steep gradient elution program (11%/min linear ramp of solvent B, solvent B ∼99% MeOH) and a washing step (80% solvent B), followed by return to the initial conditions with only 1.5 minutes required to achieve column re-equilibrium. The total injection to re-equilibration time was achieved in 8 minutes, representing a substantial throughput enhancement as compared to the previously reported methodology [19]. The adopted solvent program (details presented in the experimental section) allowed the loading of a relatively large volume injection (50 μl applied to a 2.1 mm i.d. column), and when followed by the previously noted steep gradient program, resulted in excellent sensitivity (details provided in a latter section) without the need for pre-concentration during sample preparation. A typical chromatogram of the analyte present in aqueous solution is provided in Figure 3A, where the elution time is noted as ∼2.7 minutes.

3.2 Internal standard selection

The incorporation of an internal standard (IS) generally adds to the quantitative robustness of bioanalytical methods. With regard to physical-chemical properties, an ideal situation occurs when the IS exhibits similar solubility, chemical reactivity, ionization constants, possesses a closely matched chemical structure as compared to the analyte of interest. The closest match occurs with the use of a stable isotope modification of the analyte, which is especially useful for LC-MS/MS based methodology. In the present case, stable isotope labeled carbamathione is not readily available, nor are any (isotope labeled) precursors or building blocks that would allow for a straight forward synthesis of this molecule. Accordingly, efforts were directed to obtaining five IS candidates offering appropriate chromatographic and MS fragmentation characteristics.

As with carbamathione, all of these substances can be viewed as straightforward chemical elaborations of glutathione, and can be categorized into three different categories based on their functional groups present. They are seen to be an S-n-alkyl-glutathione derivative (Figure 2A) that deviates the most from carbamathione, having an alkyl moiety bonded to the cysteine sulfur and thus lacking the carbamoyl linkage, three S-(N-mono-n-alkylcarbamoyl)glutathiones (Figure 2B-2D) each possessing the carbamoyl linkage of carbamathione, but with only a single alkyl group present on the nitrogen and an S-(N,N-di-n-alkylcarbamoyl)glutathione (Figure 2E), that possesses a tertiary carbamoyl moiety (two alkyl substituents on the carbamoyl nitrogen) that closely mimics the structure of carbamathione.

In order to determine the optimal internal standard for the quantitation of carbamathione, the properties of the five IS candidates were investigated with respect to their LC retention times and fragmentation during collision induced dissociation (CID). As expected, the various potential internal standards showed significant differences in retention time (Figure 3B) and bracketed the elution window of carbamathione (Figure 3A). As regards MS/MS detection criteria, the CID fragmentation patterns of each substance are shown in Figure 3. From these results, the most sensitive mass transition for each IS candidate was selected for evaluation against that of carbamathione (Table 1). Based only on retention time, S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione (Figure 2C) would seem to be the preferred internal standard as it co-elutes with carbamathione (Figure 3). However, this substance is isobaric with carbamathione and as a result this internal standard candidate would only be suitable if it offered a unique CID fragment (compare figure 2C to 2F). Several unique transitions are present, however, crosstalk between carbamathione and S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione SRM channels could not be avoided (note the low intensity 364→278 transition, which is the major carbamathione transition) regardless of which transition was selected. The difficulty of avoiding the cross talk, presumably with low abundance glutathione backbone fragments, required a reevaluation of internal standard selection criteria. Note that the CID spectra of S-alkyl- and S-(N-alkylcarbamoyl) glutathiones are dominated by backbone fragments (Figures 2A-2D) and have common low mass fragments below m/z 200.

Moving to other candidates exhibiting a different retention times as compared to carbamathione, alleviates LC co-elution and provides unique fragmentation products amenable to quantitation. Comparing the S-(N-mono-n-alkyl) secondary carbamoyl derivatives (Figure 2B, 2C and 2D) to the tertiary carbamoyl group of carbamathione (Figure 2F) suggests the tertiary carbamoyl group stabilizes a side chain only fragment. This motivated the synthesis of S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione (Figure 2E). As expected, the E CID spectrum has abundant carbamoyl related fragments and at optimum CE the m/z 128 fragment dominates the CID spectra, which is similar to the dominant carbamoyl related m/z 100 fragment of carbamathione. Based on these results, substance E (Figure 2) was selected as the IS for the plasma assay of carbamathione.

3.3 Sample preparation

The polar analyte glutathione can be extracted efficiently out of human plasma by various acid mediated protein precipitation procedures, followed by centrifugation [21, 22]. The resulting aqueous solution is compatible with a reversed phase HPLC separation, resulting in a convenient sample preparation strategy. Since the targeted analyte and IS are each simple chemical elaborations of glutathione, acid mediated protein precipitation was evaluated as an approach to sample deproteinization. Accordingly, aqueous and plasma samples containing carbamathione were prepared and subjected to perchloric acid (PCA) mediated protein precipitation (n=5). After recovery of the resulting supernatant, analyte determination revealed recovery of 98.1 ± 2.0 % for plasma with respect to the aqueous standards. Due to this result other acids were not investigated However, to determine if unknown plasma components present in the deproteinized plasma supernatant resulted in an altered MS ionization process, a post-column infusion of carbamathione and the IS was conducted. The results obtained revealed that in the elution window of interest there was no endogenous compound interference or ion suppression. An observation that was further reinforced by the quantitative recovery of carbamathione.

With this information in place, there was still the need to evaluate the stability of the analyte in the media of various pH values expected to be encountered during the envisioned assay operations. During assay development of carbamathione present in rat brain and plasma microdialysis samples, Kaul et al. [19] found the substance to be stable in Ringer's solution at room temperature, frozen and when subjected to several freeze-thaw cycles over the analytical timeframe. However in the present work, there was need to establish solution stability over a wider pH range and in an attempt to force degradation, solutions of carbamathione were prepared at pH 1.0 to pH 8.0 and heated to 50 °C. These solutions were evaluated every 24 hours for a week with no observed degradation, thus establishing that carbamathione is stable at 50 °C for a week over the pH 1.0-8.0 range, clearly sufficient for the various analytical operations needed during plasma sample determination.

The stability of carbamathione within a plasma matrix was also evaluated (table 2). Carbamathione does demonstrate some plasma instability at room temperature, with 7.8 % degradation observed after 2 hours of incubation. The post-extraction sample was determined to be stable for at least 24 hours, which is a sufficient time-frame for LC-MS analysis (table 2). Since carbamathione is stable in both dialysates and plasma extracts, the plasma instability of carbamathione is indicative of an enzymatic degradation pathway. Therefore it is important that plasma samples are processed within 10 minutes of thawing. Since sample processing consists out of a simple protein precipitation step, this is not problematic. The freeze-thaw stability of carbamathione was analyzed by subjecting enriched samples to three freeze-thaw cycles over seven days (table 3). No significant degradation was observed over this time frame.

Table 2. Stability of carbamathione at room temperature (21° C).

| Stability in Plasma (n=5) | Stability in Supernatant (n=5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation Time (h) | Mean Observed Concentrationa (μM) | Mean Recovery (%) | RSD (%) | Mean Observed Concentrationa (μM) | Mean Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

| 2 | 138.3 | 92.2 | 7.9 | 152.4 | 101.6 | 2.39 |

| 4 | 126.7 | 84.5 | 4.2 | 149.5 | 99.7 | 2.79 |

| 6 | 108.1 | 72.1 | 4.5 | 152.2 | 101.5 | 2.21 |

| 24 | 36.1 | 24.1 | 12.3 | 142.9 | 95.2 | 1.31 |

Expected concentration for full recovery is 150 μM

Table 3.

Freeze-thaw stability of carbamathione.

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbamathione Concentration (μM) | |||

|

|

|||

| Nominal | Measured | RSD (%) | |

| Day 1 | 100 | 107.2 | 5.9 |

| 150 | 158.7 | 4.4 | |

| 200 | 202.0 | 1.7 | |

| Day 3 | 100 | 119.5 | 6.7 |

| 150 | 154.4 | 2.1 | |

| 200 | 189.1 | 4.4 | |

| Day 7 | 100 | 110.8 | 3.2 |

| 150 | 139.4 | 8.3 | |

| 200 | 192.7 | 12.2 | |

3.4 Method Linearity, Accuracy, and Precision

The linearity, accuracy and precision of the method were determined by the analysis of calibration plots ranging from 0.5 nM to 50.0 nM spiked plasma concentration (n=5 per concentration) for four consecutive days. Intra- and inter-run accuracy and precision were typically within 10% of the target value. A typical calibration curve was described by the following linear equation: y = 1.978 × − 0.039 (y = dimension less number obtained by normalization of the carbamathione response to the internal standard; x = concentration of carbamathione in nM). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) with acceptable accuracy and precision (<10%) was determined to be at 0.5 nM in plasma. While FDA guidelines state that LLOQ precisions of < 20% are acceptable, the LLOQ was not challenged further as 0.5 nM was determined to be adequate for the current investigation. The limit of detection was not challenged below 0.1 nM in plasma, while the 0.1 nM plasma sample still revealed S/N > 5. The method exhibits good intra- and inter-run linearity with R2 = 0.9972 and R2 = 0.9976, respectively. Accuracy values were within 5% of expectation and sample precision was within 10% over the validated range (Table 4).

Table 4. Summary of validation data showing intra and inter-run accuracy and precision.

| Intra-run (n = 5) | Inter-run (n = 20) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Carbamathione concentration (nM) | Mean observed concentration (nM) | Precision (RSD %) | Mean accuracy of target value (%) | Mean observed concentration (nM) | Precision (RSD %) | Mean accuracy of target value (%) |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.9 | 100.6 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 103.8 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 99.3 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 99.8 |

| 5.0 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 103.0 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 98.8 |

| 10.0 | 9.9 | 3.9 | 99.3 | 9.9 | 6.0 | 98.6 |

| 50.0 | 49.9 | 4.8 | 99.8 | 50.2 | 4.0 | 100.4 |

3.5 Human Plasma Levels

The developed carbamathione plasma assay methodology was successfully applied to determination of samples obtained from a disulfiram-dosed volunteer. Figure 4 depicts a typical chromatogram of the results obtained, in this case that of a sample obtained one hour after dosing where a chromatographic peak is observed that represents carbamathione present in a concentration of 2.1 nM. Interestingly, the various samples show an unidentified peak (Figure 4), which was detected in every sample containing carbamathione. This peak results from the MRM transition used to detect carbamathione and also matches the carbamathione profile in plasma. It is highly probable that this unknown substance results from a disulfiram metabolite possessing the carbamoyl (100 m/z) fragment. The plasma concentration profile obtained as a function of time (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 hours) subsequent to oral dosing of a healthy volunteer is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Potential internal standards and their CID fragmentation: A, S-n-butylglutathione; B, S-(N-n-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione; C, S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione; D, S-(N-n-pentylcarbamoyl)glutathione; E, S-(N,N-di-n-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione; F, carbamathione. Structures are annotated with the mass in the spectrum, backbone fragments have an additional proton to that suggested by the bars.

Figure 5.

A: HPLC/SRM chromatograms of carbamathione and 2B: Five potential internal standards A: S-n-butylglutathione, B: S-(N-n-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione, C: S-(N-n-butylcarbamoyl)glutathione, D: S-(N-n-pentylcarbamoyl)glutathione, E: S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione. SRM transitions are in Table 1, 100 nM solutions of each substance were injected.

4.0 Conclusion

A selective and sensitive method for the detection and quantification of carbamathione in human plasma has been developed. The method exhibits accuracy and precision of 5% and ≤ 10 percent, respectively, and achieves good chromatographic throughput (8 min injection to injection with a methanol:water gradient). Detection was accomplished by tandem mass spectrometry in positive ion mode, using SRM and a structural homolog, S-(N,N-di-i-propylcarbamoyl)glutathione, Figure 2,E , as the internal standard. In human plasma samples, the limit of quantification and detection were 0.5 nM and 0.1 nM, respectively. The rapid chromatographic cycle and simple sample pretreatment allow for a high sample throughput, which is very desirable for bioanalytical methodology required to support any clinical investigation. Furthermore, the method was successfully applied to biological samples and used to determine the plasma profile of carbamathione in a single human volunteer. The analysis of disulfiram-dosed volunteer plasma samples resulted in the discovery of a compound peak having a similar plasma-time profile as carbamathione. The observed compound contains a 100 m/z fragment, which is highly suggestive that it is related to the carbamoyl fragment observed for carbamathione.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Justin T. Douglas for expertise and the acquisition of the NMR data. The Micromass Ultima was purchased with support from the KU Research Development Fund and the Acquity UPLC with partial support from K-INBRE (www.kumc.edu/kinbre/) (TDW). This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse of the National Institute of Health to EFM grant number K24 DA 023359 and RO1 DA 024982 and to MDF grant number DA 021727.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hald J, Jacobsen E. A drug sensitizing the organism to ethyl alcohol. Lancet. 1948:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(48)91514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yourick Jeffrey J, Faiman Morris D. Disulfiram metabolism as a requirement for the inhibition of rat liver mitochondrial low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:1361–1366. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90446-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson B, Stankiewicz Z. Inhibition of erythrocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase activity and elimination kinetics of diethyldithiocarbamic acid methyl ester and its monothio analogue after administration of single and repeated doses of disulfiram to man. Europ J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;37:133–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00558220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yourick JJ, Faiman MD. Comparative aspects of disulfiram and its metabolites in the disulfiram-ethanol reaction in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:413–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart BC, Faiman MD. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of rat liver aldehyde dehydrogenase by S-methyl N,N-diethylthiolcarbamate sulfoxide, a new metabolite of disulfiram. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:403–406. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90555-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madan A, Parkinson A, Faiman MD. Identification of the humand and rat P450 enzymes responsible for the sulfoxidation of s-methyl N,N-diethylthiolcarbamate (DETC-Me) Drug Metabol Disp. 1995;23:1153–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pike MG, Martin YN, Mays DC, Benson Linda M, Naylor S, Lipsky JL. Roles of FMO and CYP 450 in the Metabolism in Human Liver Microsomes of S-Methyl-N,N-Diethyldithiocarbamate, a Disulfiram Metabolite. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagendra SN, Madan A, Faiman MD. S-Methyl N,N-diethylthiolcarbamate sulfone, an in vitro and in vivo inhibitor of rat liver mitochondrial low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochem Pharmcol. 1994;47:1465–1467. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagendra SN, Faiman MD, Davis K. Carbamoylation of brain glutamate receptors by disulfiram metabolite. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24247–24251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G. Master's thesis. University of Kansas; 1999. The chemistry of carbamoyl thioester sulfoxides in vitro and in vivo. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, et al. Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction. 1998;93:713–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, et al. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrakis IL, Carroll KM, Nich C, et al. Disulfiram treatment for cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained opioid addicts. Addiction. 2000;95:219. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9522198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George TP, Chawarski MC, Pakes J, et al. Disulfiram versus placebo for cocaine dependence in buprenorphine-maintained subjects a preliminary trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, et al. A double blind, placebo-controlled trial that combines disulfiram and naltrexone for treating co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. Addiction behavior. 2008;33:651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faiman MD, Artman L, Haya K. Disulfiram distribution and elimination in the rat after oral and intraperitoneal administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1980;4:412–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb04841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faiman MD, Artman L, Maziasz T. Diethyldithiocarbamic acid-methyl ester distribution, elimination, and LD50 in the rat after intraperitoneal administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1983;7:307–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin L, Davis MR, Hu P, Baillie TA. Identification of novel glutathione conjugates of disulfiram and diethyldithiocarbamate in rat bile by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Evidence for metabolic activation of disulfiram in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:526–533. doi: 10.1021/tx00040a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul S, Williams TD, Lunte CE, Faiman MD. LC-MS/MS determination of carbamathione in microdialysis samples from rat brain and plasma. J Pharm Biochem Analysis. 2010;51:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han DH, Pearson PG, Baillie TA, Dayal R, Tsang LH, Gescher A. Chemical synthesis and cytotoxic properties of N-alkylcarbamic acid thioesters, metabolites of hepatotoxic formamides. Chem Res Toxicol. 1990;3:118–124. doi: 10.1021/tx00014a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monostori P, Wittmann G, Karg E, Túri S. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples: an in-depth review. J Chrom B. 2009;877:3331–3346. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camera E, Picardo M. Analytical methods to investigate glutathione and related compounds in biological and pathological processes. J Chrom B. 2002;781:181–206. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]