Abstract

Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon spp. have increased considerably in recent years, especially in neutropenic and critically ill patients using catheters and antibiotics. The genus presents limited sensitivity to different antifungal agents, but triazoles are the first choice for treatment. Here, we investigated the biofilm production and antifungal susceptibility to triazoles and amphotericin B of 54 Trichosporon spp. isolates obtained from blood samples (19), urine (20) and superficial mycosis (15). All isolates and 7 reference strains were identified by sequence analysis and phylogenetic inferences of the IGS1 region of the rDNA. Biofilms were grown on 96-well plates and quantitation was performed using crystal violet staining, complemented with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Susceptibility tests for fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole and amphotericin B were processed using the microdilution broth method (CLSI) for planktonic cells and XTT reduction assay for biofilm-forming cells. Our results showed that T. asahii was the most frequent species identified (66.7%), followed by T. faecale (11.1%), T. asteroides (9.3%), T. inkin (7.4%), T. dermatis (3.7%) and one T. coremiiforme (1.8%). We identified 4 genotypes within T. asahii isolates (G1, G3, G4 and G5) and 2 genotypes within T. faecale (G1 and G3). All species exhibited high adhesion and biofilm formation capabilities, mainly T. inkin, T. asteroides and T. faecale. Microscopy images of high biofilm-producing isolates showed that T. asahii presented mainly hyphae and arthroconidia, whereas T. asteroides exhibited mainly short arthroconidia and few filaments. Voriconazole exhibited the best in vitro activity against all species tested. Biofilm-forming cells of isolates and reference strains were highly resistant to all antifungals tested. We concluded that levels of biofilm formation by Trichosporon spp. were similar or even greater than those described for the Candida genus. Biofilm-forming cells were at least 1,000 times more resistant to antifungals than planktonic cells, especially to voriconazole.

Introduction

Trichosporon spp. are basidiomycetous yeast-like organisms that are widely distributed in nature, and can generally be isolated from soil, water, decomposing matter, and bird and bat droppings [1]. Occasionally, it can be part of the transient human microbiota, mainly in the skin, nails and mucosa of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [1], [2]. According to data provided by the ARTEMIS DISK collection, Trichosporon spp. are considered to be the second or third most commonly isolated yeast species in clinical laboratories, representing 5.5 to 10.6% of all isolates [3], [4], [5].

Trichosporon sp. has been classically associated with white piedra and hypersensitivity pneumonitis syndrome [1], [6], [7], [8], [9]. However, in recent decades, Trichosporon sp. has been recognized as an important pathogen of systemic infections affecting immunocompromised patients, mainly those with hematological malignancies and neutropenia, as well as critically ill patients with a central venous catheter in place [10], [11], [12], [13].

The genus contains 51 species, 16 of which are able to infect human hosts [1]. Species identification based on phenotypic methods usually generates inconsistent results, and none of the commercially available tests includes new species in the genus in their databases [14]. Consequently, sequencing of the Intergenic Spacer 1 (IGS1) of the rDNA, which presents high variability within the genus, is a robust method to identify medically important Trichosporon species [15], [16].

There are only a few studies addressing virulence factors in Trichosporon spp., including biofilm production [17], [18], [19]. In addition, there is a lack of information on the antifungal susceptibility of T. asahii and clinically relevant emergent species within the genus. Most studies have adapted the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) microdilution method standardized for testing Candida spp. and Cryptococcus spp. to evaluate the in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Trichosporon spp. [12], [20], [21], [22]. Available data suggest that triazoles appear to be the most effective antifungal class against Trichosporon spp. [21], [23], [24], [25].

Different species within a genus may have biological peculiarities regarding their virulence mechanisms and drug susceptibility. In this study, we evaluated the biofilm formation and antifungal susceptibility profile of 54 clinical isolates of Trichosporon spp., whose species identification was confirmed by sequencing the IGS1 region of the rDNA.

Materials and Methods

Isolates and growth conditions

We tested a total of 54 clinical isolates of Trichosporon spp. obtained from different patients assisted between 2001 and 2010. Due to the retrospective character of the study, no informed consent was required for the IRB Commitee approval. Ethics Committee number 1497/11. The strains were obtained from blood (19), urine (20) and superficial sites (skin and hair) (15). Isolates were sent to the Laboratório Especial de Micologia, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, for identification and antifungal susceptibility testing. In addition, the following 7 Trichosporon spp. and 2 Candida spp. reference strains were added as controls: T. asahii (CBS 2479 e CBS 7631), T. inkin (CBS 5585), T. dermatis (CBS 2043), T. faecale (CBS 4828), T. mucoides (CBS 7625), T. ovoides (CBS 7556), C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) and C. krusei (ATCC 6258). All isolates were stored at −80°C in liquid YEPD medium plus 20% glycerol. Prior to all experiments, the isolates were transferred twice in CHROMagar Candida for 48 h at 35°C to evaluate their viability and purity.

Screening of the Trichosporon genus

Phenotypic identification of the genus relied on the macro and micromorphological (presence of arthroconidia) characteristics of the colonies as well as a positive urea hydrolysis test [26].

Molecular identification of Trichosporon sp. isolates

Molecular identification was performed by amplification and sequencing of the IGS1 region from the rDNA according to the protocol previously described [27]. Sequencing of 2 to 4 reads per isolate was performed with the BigDye T'erminator Kit (Applied Biosystems) protocol, and the final sequence was obtained after alignment and edition in SequencherTM 4.1.4 - Gene Codes. Final species identification was obtained by comparisons with the NCBI database (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the BLASTn tool. We considered as criteria for species identification identity and sequence coverage ≥ 98% and E-value <10−5 [27], [28].

Genotyping analysis

Sequences of the IGS1 region of rDNA from all identified T. asahii and T. faecale isolates were aligned with sequences of species deposited in the GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) to check for the presence of genotypes 1 to 12 in T. asahii and 1 to 3 in T. faecale. Alignments were performed using the muscle algorithm implemented by SEAVIEW 4.2.12 and adjusted by eye before haplotype and phylogenetic analyses [29]. Haplotype analysis was implemented in the DNAsp 5.0, excluding gap positions [30]. Median-joining network was constructed and visualized using the software Network 4.610 [31]. Bayesian analysis was performed in MrBayes 3.02 [32].

Biofilm formation

To assess biofilm formation of Trichosporon spp. isolates in a 96-well plate format, we standardized a protocol adapted from Jin et al. (2003) and di Bonaventura et al. (2006) [33], [34]. We tested different protocol conditions, such as: inoculum size (105, 106 and 107 cells/ml), adhesion time (60, 90 and 120 min), and biofilm maturation (48 and 72 h) with static or shaking (75 rpm) incubation at 37°C. We used the isolates C. tropicalis LEMI 651 and C. metapsilosis LEMI 1799 as control strains because they were previously characterized as being high and low biofilm producers, respectively, by Melo et al. (2011) [35]. Clinical isolates and control strains were cultured in YPD at 35°C for 48 h and further subcultured under agitation in RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.0 - MOPS) overnight at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with sterile PBS. Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (pH 7.0 - MOPS) and the inoculum adjusted to 0.4 O.D. at 530 nm (A530), which corresponds to 107 cells/ml. Inocula of 100 µl of the cell suspensions were added to 96-well polystyrene plates with flat bottoms (Techno Plastic Products, TPP, Switzerland), using 8 wells per isolate. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min with agitation at 75 rpm. After incubation, cells were aspirated, and wells were washed twice with 150 µl PBS to remove the non-adherent cells. Finally, 150 µl RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.0 - MOPS) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C and 75 rpm for 48 h to allow biofilm formation. Culture media were changed every 24 hours. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and biofilm quantifications are expressed as means of 24 readings (wells) per isolate ± standard deviation.

Biofilm quantification with crystal violet staining

Mature biofilms had the culture medium aspirated, and they were washed twice with 200 µl sterile PBS to remove non-biofilm-forming cells. For quantification using crystal violet staining, plates were dried for 45 min at room temperature. Biofilms were stained with 110 µl 0.4% aqueous crystal violet (CV) solution for 45 min. Afterwards, the CV solution was removed, and the wells were washed 3 to 5 times with 200 µL sterile distilled water. To destain the biofilms, 200 µl 95% ethanol was added, and the plate was incubated for 45 min. One hundred μl of the solution were transferred to another microplate, and the absorbance was read using a Microplate Reader 680 (BIO RAD, Hercules, USA) at 570 nm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy was performed with 3 T. asahii and 1 T. asteroides isolates selected based on their biofilm production capabilities. Biofilms were formed on sterile polyvinyl chloride (PVC) strips (surface area, 0.5 cm2), incubated into 24-well polystyrene plates with flat bottoms (Techno Plastic Products, TPP, Switzerland), according to the protocol described previously [36]. Briefly, all biofilms formed on PVC strips were fixed overnight at 4°C with a solution composed by 4% formaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate at pH 7.2. Subsenquently, biofilms were washed repeatedly with 1% osmium tetroxide buffered with cacodylate for 1 h, then treated with 1% tannic acid for 45 min, washed three times with distilled water for 15 min, and finally, treated with 1% osmium tetroxide buffered with cacodylate for 1 h. Biofilms were dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol washes (critical-point dried in CO2) and coated with gold to be analyzed in the scanning electron microscope JEOL JSM-5300 (Peabody, MA, USA).

Antifungal susceptibility testing against planktonic and biofilm-forming cells

We adapted the assay conditions of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution method (CLSI, M27-A3/S4) to evaluate the response of planktonic fungal cells to the following drugs: fluconazole (FLC), itraconazole (ITC), voriconazole (VRC) and amphotericin B (AMB). Antifungal compounds were obtained as pure powders from the manufacturers Pfizer Inc., NY, USA and Sigma Chemical Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA. Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and C. krusei ATCC 6258 were used as controls.

Susceptibility tests for biofilm-forming cells were processed following the protocol previously described by Melo et al. (2011) [35]. Biofilms were grown for 24 h before replacement of the medium with fresh RPMI 1640 (pH 7.0 - MOPS) supplemented with the antifungals at the following concentrations: FLC (64-1024 µg/ml), ITC (1–16 µg/ml), VRC (4–64 µg/ml) and AMB (2–32 µg/ml). Biofilms were grown for 48 h and quantified afterwards using the XTT reduction assay. For the XTT (2,3-Bis-(2-Methoxy-4-Nitro-5-Sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium-5-Carboxanilide) reduction assay, a solution containing 200 µl PBS with 12 µl 5:1 1 mg/ml XTT (Sigma Aldrich): Menadione 0.4 mM (Sigma Aldrich) was used. The plate was incubated for 2 h at 35°C in the dark to allow XTT metabolization. Thereafter 100 µl of this solution was transferred to another microplate, and the absorbance was read using a Microplate Reader 680 (BIO RAD, Hercules, USA) at 490 nm.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) of the drugs on planktonic cells were determined by visual readings after 48 h of incubation based on the lower concentration capable of inhibiting 50% of cell growth for azoles and total growth inhibition for AMB. Biofilm MICs at 48 h were defined as the lowest concentration capable of inhibiting 50% and 80% of cell growth for azoles and AMB, respectively [35].

Statistical analysis

We performed comparisons between MIC values generated by T. asahii and non-T. asahii isolates as well as the biofilm production among different genotypes of T. asahii and T. faecale, applying the Mann-Whitney test implemented in the GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (http://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/6/statistics/).

Results

Phenotypic and molecular identification of Trichosporon isolates

All 54 clinical and 7 reference strains of Trichosporon spp. included in the analysis were considered pure and viable and presented morphological and biochemical characteristics compatible with the Trichosporon genus. DNA sequences of the IGS1 region of the rDNA from all isolates ranged from 435 to 630 bp after contig assembly and editing. For species identification, alignments performed with the BLASTn tool successfully identified 58 of 61 Trichosporon spp. isolates with query coverage ≥99%, identity ≥99%, and E-value = 0.0. Three T. faecale isolates (ST004B, EB087B and EB108A) generated lower identity or coverage values in the BLASTn searches, 96% and 97%, respectively. Therefore, their species identification was further confirmed by phylogenetic analysis (Figure S1). The 54 clinical isolates were identified as follows: 36 T. asahii, 6 T. faecale, 5 T. asteroides, 4 T. inkin, 2 T. dermatis and 1 T. coremiiforme (Table 1 and Table S1).

Table 1. Species distribution of 54 Trichosporon spp. clinical isolates according to the site of infection or colonization identifiyed by IGS1 rDNA sequencing.

| Species | Number of Isolates/Source | Total/Percentage | ||

| Blood | Urine | Superficial Mycosis or Skin Colonization | ||

| T. asahii | 12 | 20 | 4 | 36/66.7% |

| T. faecale | - | - | 6 | 6/11.1% |

| T. asteroides | 5 | - | - | 5/9.3% |

| T. inkin | - | - | 4 | 4/7.4% |

| T. dermatis | 1 | - | 1 | 2/3.7% |

| T. coremiiforme | 1 | - | - | 1/1.8% |

| Total | 19 | 20 | 15 | 54/100% |

Genotyping of T. asahii and T. faecale isolates

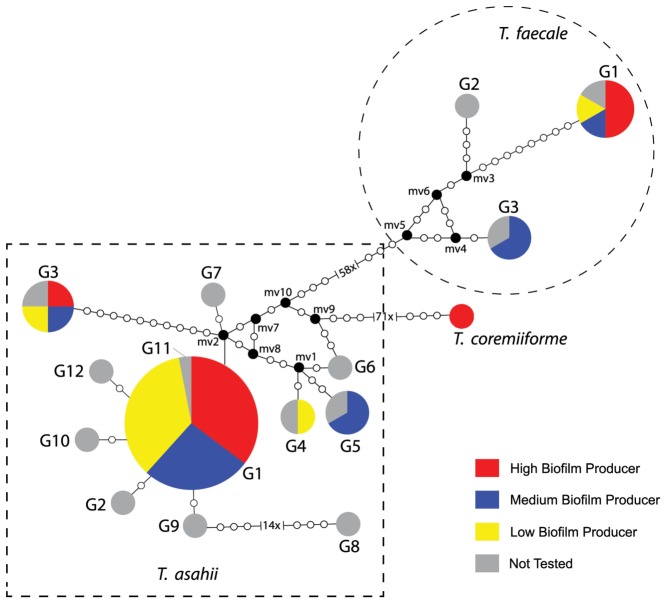

Clinical isolates identified by IGS1 rDNA sequencing as T. asahii (36) and T. faecale (6) were subjected to phylogenetic analysis to confirm their identification and characterize their genotypes (Figure 1 and Figure S1). The network analysis (Figure 1) showed that 36 clinical isolates identified as T. asahii grouped into 4 different genotypes: 1, 3, 4 and 5. Trichosporon asahii G1 comprised 30 clinical isolates, the 2 reference strains CBS 2479 and CBS 7631, the G1 reference sequence (GenBank number: AB066386) and the supposedly G11 reference sequence (GenBank number: EU441160); T. asahii G3 consisted of 3 clinical isolates and the G3 reference sequence (GenBank number: AB066397); T. asahii G4 grouped 1 clinical isolate and the G4 reference sequence (GenBank number: AB180191); and T. asahii G5 included 2 clinical isolates and the G5 reference sequence (GenBank number: AB071387). The other reference sequences obtained from GenBank that did not grouped with our clinical isolates were: G2: AB072606, G6: AB180192, G7: AB180194, G8: AB439002, G9: AB439003, G10: EU441158, and G12: JF412789. Four of 6 T. faecale clinical isolates and the T. faecale CBS 4828 were classified as genotype 1 (G1 reference sequence number: AB066413). The isolates EB087B and EB108A had their molecular identification confirmed as T. faecale genotype 3 (G3 reference sequence number: AB439006). Trichosporon faecale G2 reference sequence (GenBank number: AB439004) did not group with any of the clinical isolates.

Figure 1. Median-joining genotypes network of T. asahii, T. faecale and T. coremiiforme based on IGS1 rDNA sequences related to biofilm quantitation.

Dashed square groups the 12 different genotypes (G1 to G12) of T. asahii. Dashed circle groups the 3 different genotypes of T. faecale. Circumference sizes are proportional to the genotype frequencies. Black dots (mv = median vectors) are hypothetical missing intermediates.

The consensus tree inferred by the Bayesian method (Figure S1) corroborated the network analysis, confirming the identification of T. asahii isolates within 4 different genotypes, including the first-time identification of the genotype 5 among Brazilian isolates and the identification of ST004B, EB087B and EB108A as T. faecale isolates.

Biofilm production by Trichosporon spp

In a pilot study it was tested the protocol conditions for Trichosporon spp. biofilm formation into 96-well plates. We observed that 107 cells/ml, 90 min adhesion time and 48 h biofilm growth at 75 rpm provided the most reproducible results than the other combinations (data not shown). Comparative analysis of the quantification by CV method of biofilms grown during 48 and 72 h showed that the last time point returned lower absorbance values than the first one due to biofilm detachment from the wells, mostly from isolates that were further classified as high biofilm producers (data not shown).

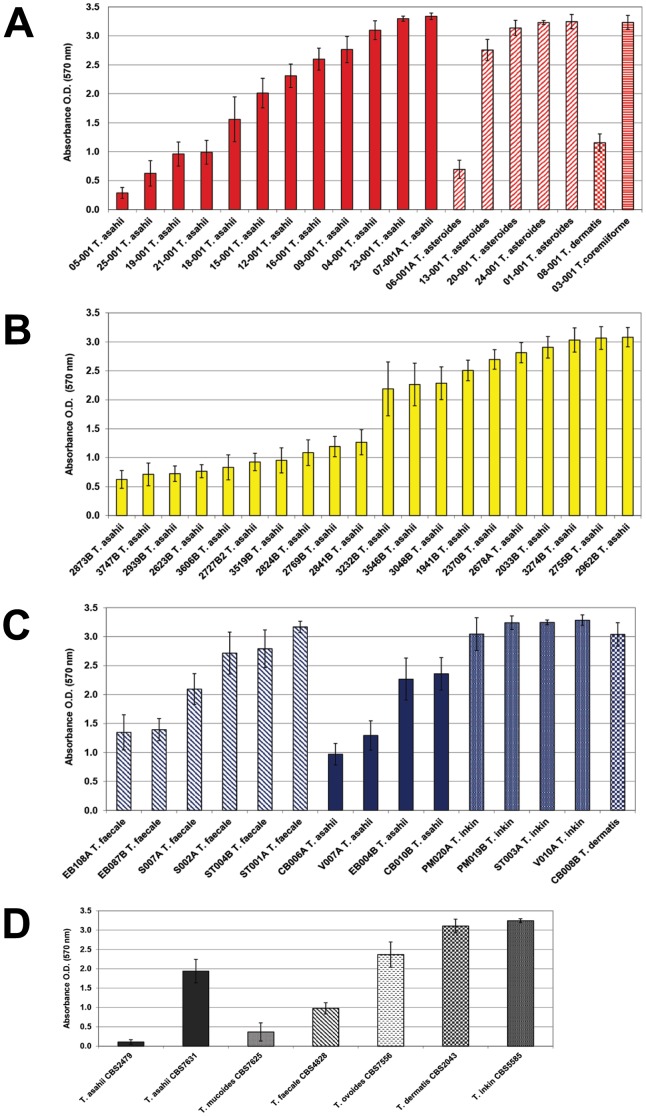

The total biofilm mass of 54 clinical isolates and 7 reference strains of Trichosporon spp. was then assessed by CV staining after 48 h growth. Absorbance values ranged from 0.109 to 3.337. To correlate the capability for biofilm production with the different species tested and isolation sites, we arbitrarily established three categories (33.3 percentiles) of biofilm production based on the total range of the CV quantifications exhibited by the 61 isolates, categorizing the producers as follows: low: A570<1, medium: A570≥1.01 to 2.499 or high: A570≥2.5. Figure 2 illustrates the biofilm production by all strains tested according to the isolation source and species distribution. Trichosporon sp. strains were scaled from the highest to the lowest biofilm producer as T. inkin> T. asteroides ≈ T. faecale> T. asahii. The two T. dermatis isolates (classified as medium and high biofilm producers) and the single T. coremiiforme isolate (high biofilm producer) were not included in this rank scale due to the low number of isolates tested. When considering the source of isolation, 93.3% of the Trichosporon spp. strains isolated from skin were categorized as high or medium biofilm producers. Otherwise, 65% to 73.7% of the strains isolated from blood and urine, respectively, were considered high or medium biofilm producers. The reference strains were characterized as low (T. asahii CBS2479, T. mucoides CBS7625 and T. faecale CBS4828), medium (T. asahii CBS7631 and T. ovoides CBS7556) or high (T. dermatis CBS2043 and T. inkin CBS5585) biofilm producers.

Figure 2. Inter and intra species variation in the biofilm production of 54 Trichosporon spp. clinical isolates and 7 reference strains.

A- 19 isolates from blood identified as T. asahii, T. asteroides, T. coremiiforme and T. dermatis. B- 20 isolates from urine identified as T. asahii. C- 15 isolates from superficial mycosis/skin colonization identified as T. asahii, T. dermatis, T. faecale and T. inkin. D- 7 reference strains from CBS obtained from different sources.

There were no significant differences in terms of biofilm production across different genotypes identified within T. asahii and T. faecale isolates (Figure 1).

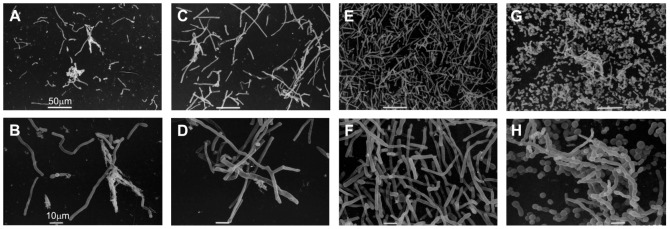

Biofilm Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis (SEM) of Trichosporon spp. isolates

To check the efficiency of the CV method to quantify biofilms of Trichosporon spp., we generated SEM images of 4 Trichosporon spp. strains categorized as low, medium and high biofilm producers. The following isolates were analyzed: T. asahii 05-001 (CV-A570 = 0.287), T. asahii 18-001 (CV-A570 = 1.557), T. asahii 07-001A (CV-A570 = 3.337) and T. asteroides 13-001 (CV-A570 = 2.755). We observed that all T. asahii isolates produced micromorphology enriched with hyphae and arthroconidia regardless of the category of biofilm production (Figure 3 A to F). Notably, the T. asteroides strain classified as high biofilm producer exhibited a predominance of blastoconidia and arthroconidia, with a few filaments (Figure 3 G and H). We found a high correlation between SEM images and biofilm quantification by CV staining in the categorization of isolates as low or high biofilm producers.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy of 4 Trichosporon spp. strains grown on catheter surfaces.

A and B: Low biofilm producer T. asahii 05-001 (CV-A570 = 0.287); C and D: Medium biofilm producer T. asahii 18-001 (CV-A570 = 1.557); E and F: High biofilm producer T. asahii 07-001A (CV-A570 = 3.337); and G and H: High biofilm producer T. asteroides 13-001 (CV-A570 = 2.755).

Susceptibility of planktonic and biofilm-forming cells of Trichosporon spp. isolates against 4 antifungal agents

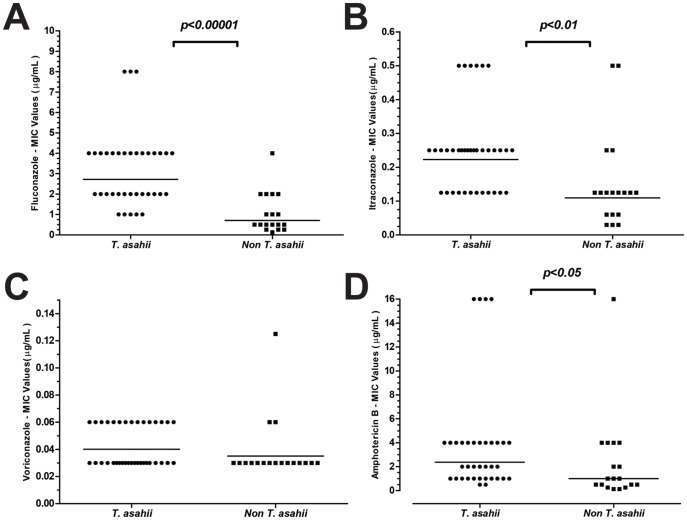

The MIC readings of susceptibility tests for both planktonic and biofilm forming cells were performed after 48 h of incubation. Table 2 summarizes the planktonic MIC50, MIC90, and MIC ranges (μg/ml) and the geometric means (GM) obtained for the 54 clinical isolates of Trichosporon spp. against 4 antifungal agents. Of note, T. asahii, T. asteroides and T. faecale isolates exhibited MIC50 values for AMB ≥2 µg/ml. Trichosporon asahii isolates exhibited higher MIC values for all antifungals tested except for VRZ (Table 2 and Figure 4). Figure 4 depicts the comparison between MIC values obtained for T. asahii and non-T. asahii isolates. In general, significant differences were found between the two groups considering FLC, ITC and AMB, whereas VOR was the azole that exhibited the best in vitro activity against all Trichosporon species.

Table 2. In vitro activity of 4 antifungal drugs against planktonic cells of 54 clinical isolates of Trichosporon spp. according to the isolation site.

| Species/Blood culture (Number of isolates) | MIC (μg/ml) | |||||||||||||||

| Fluconazole | Itraconazole | Voriconazole | Amphotericin B | |||||||||||||

| Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | GM | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | GM | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | GM | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | GM | |

| T. asahii (12) | 1–8 | 2 | 8 | 2.67 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.22 | 0.03–0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.032 | 1–16 | 2 | 16 | 2.57 |

| T. asteroides (5) | 0.25–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.38 | 0.06–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.108 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.5–16 | 4 | 4 | 3.03 |

| T. dermatis (1) | 2 | - | - | - | 0.125 | - | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | - |

| T. coremiiforme (1) | 0.5 | - | - | - | 0.125 | - | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | - |

MIC50: Minimal inhibitory concentration capable of inhibiting growth of 50% of isolates.

MIC90: Minimal inhibitory concentration capable of inhibiting growth of 90% of isolates.

GM: Geometric Mean.

Figure 4. Comparative analysis of MIC values obtained against planktonic cells of T. asahii (36 isolates) versus non-T. asahii (18) isolates for all antifungals tested.

A- Fluconazole; B- Itraconazole; C- Voriconazole and D- Amphotericin B.

We were not able to compare whether the isolation site had an impact on the antifungal susceptibility profiles of the Trichosporon spp. strains because a clear bias of the species distribution was observed, e.g., T. faecale was identified only among superficial mycosis isolates, and all isolates identified in urine samples were T. asahii.

Table 3 summarizes MIC values for all antifungals testes against biofilm-forming cells. Regardless of the Trichosporon spp. species or isolation site, all strains were highly resistant to all antifungals tested.

Table 3. In vitro activity of 4 antifungal drugs against biofilm forming cells of 54 clinical isolates of Trichosporon spp.

| Species (Number of isolates) | MIC (μg/ml) | |||||||||||

| Fluconazole | Itraconazole | Voriconazole | Amphotericin B | |||||||||

| Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | Interval | MIC50 | MIC90 | |

| T. asahii (36) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

| T. faecale (6) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

| T. asteroides (5) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

| T. inkin (4) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

| T. dermatis (2) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

| T. coremiiforme (1) | - | >1024 | >1024 | - | >16 | >16 | - | >64 | >64 | - | >32 | >32 |

MIC50: Minimal inhibitory concentration capable of inhibiting growth of 50% of isolates.

MIC90: Minimal inhibitory concentration capable of inhibiting growth of 90% of isolates.

Discussion

Trichosporon sp. isolates are classically recognized as a cause of superficial mycoses but have recently emerged as pathogens in invasive infections, particularly in patients with acute leukemia and those subjected to invasive clinical procedures [10], [37]. It is still controversial whether there is bias in the distribution of Trichosporon species among different sites of infection as well as other putative biological peculiarities of the large number of recently described species within the genus, such as antifungal susceptibility and virulence. In this study, we showed that 6 Trichosporon species from 54 clinical isolates obtained from different types of human infections were able to form robust biofilms in vitro that were not susceptible to triazoles or amphotericin B.

Regarding the species distribution within different human sites, we found that T. asahii was the most frequently isolated species (36 of 54 isolates) in both blood and urine samples, as previously described by other studies [12], [25], [38], [39]. In addition to T. asahii, other publications reported that T. mucoides and T. asteroides are among the species most isolated from invasive fungal infections due to Trichosporon spp. [27], [40]. Curiously, we were not able to isolate any other species than T. asahii from urine samples. In contrast, in superficial mycosis or skin colonization, T. inkin, T. ovoides and T. cutaneum are most commonly found [1]. At this site, the majority of the isolates were identified by IGS1 rDNA sequencing as T. faecale, followed by T. inkin and T. asahii.

Phylogenetic analysis of IGS1 sequences confirmed the presence of 4 different genotypes among T. asahii isolates, with G1 being the most prevalent in Brazil as previously documented by our group [27]. Interestingly, we found isolates belonging to T. asahii G5 and T. faecale G1 and G3 for the first time among Brazilian isolates. Recently, Xia and collaborators (2012) described three new genotypes of T. asahii: G10, G11 and G12 [41]. In our analysis, we failure to differentiate G11 reference sequence from G1 representatives. Refinement in the analysis of genotypes including a larger number of isolates is mandatory to resolve whether or not G11 is a novel genotype or represents an artifact due to IGS1 sequencing error.

Fungal biofilm formation has gained attention among clinicians specifically due to its capability to increase mortality in patients with Candida spp. fungemia [42]. In our work, we quantified the in vitro biofilm formation of 54 clinical isolates belonging to different Trichosporon species by using the crystal violet staining method. We verified that isolates representative of the 6 Trichosporon species tested have a high production of biofilms with quantification values similar to or higher than those described for Candida spp. In addition, it seems that Trichosporon spp. are able to produce much more biofilm than other basidiomycetes, such as Rhodotorula spp. and Cryptococcus spp. [35], [36], [43], [44]. Despite some intraspecific variations in biofilm production, it is clear that more than half of the isolates representative of different Trichosporon species were considered to be high biofilm producers in blood, urine and skin samples. Interestingly, non-T. asahii isolates obtained from superficial samples produced the same amount or even more biofilms compared with strains isolated from blood samples. This finding may reflect the need for high adherence and biofilm formation to promote colonization and infection on the skin and in hair samples of human hosts. In the literature, there are only 3 published studies evaluating slime or biofilm production, and these exclusively test T. asahii isolates [19], [34], [45]. Therefore, to our knowledge, this is the first time that it has been shown that non-T. asahii isolates are high biofilm producers.

As already demonstrated with Candida spp. and Rhodototula spp. strains [35], [36], CV is a reliable tool to accurately quantify the whole biofilm mass produced by fungal cells. Indeed, we succeeded in demonstrating that the protocol for biofilm formation on 96-well plates and the quantification by CV staining exhibited good correlation with SEM images.

After adapting the CLSI protocol for antifungal susceptibility testing of planktonic cells, we found that AMB has limited in vitro antifungal activity against T. asahii, T. asteroides and T. faecale. Not surprisingly, we found that T. asahii isolates exhibited higher MICs for FLC, ITC and AMB that non-T. asahii isolates, corroborating the results of other studies [22], [24], [27], [46]. As already observed, VRC presented the best antifungal activity across all species tested [24], [46]. Considering that triazoles are the antifungal agents used for first-line treatment of infections caused by Trichosporon spp., the presence of isolates with high MICs for this drug class is disturbing. The susceptibility of biofilm-forming cells demonstrated that all 6 species were intrinsically resistant to all antifungal agents tested, independent of genotype, isolation site and biofilm quantification. Considering that voriconazole is supposed to be the best alternative to treat deep-seated infections caused by Trichosporon spp., it is disturbing to observe that biofilm-forming cells presented MICs at least 1,000 times higher than planktonic cells. Indeed, serum concentrations of the four antifungal agents tested are substantially lower than the MIC values that we obtained with all Trichosporon spp. biofilm forming cells. Recently, Sun et al. (2012) [19] provided data suggesting that triazoles, AMB and 5-FC are all inefficient against T. asahii biofilms.

In conclusion, we succeeded in demonstrating that not only T. asahii but also 5 other species of the genus are able to produce high amounts of biofilms that impair the efficacy of all antifungal drugs against biofilm-forming cells. Further studies are necessary to evaluate whether this finding may correlate with the poor clinical response observed in a substantial number of patients with deep-seated infections due to emergent Trichosporon spp.

Supporting Information

Phylogenetic tree and genotypes of 36 T. asahii and 6 T. faecale isolates inferred by the Bayesian method. Reference sequences obtained from GenBank of T. asahii were G1: AB066386, G2: AB072606, G3: AB066397, G4: AB180191, G5: AB071387, G6: AB180192, G7: AB180194, G8: AB439002, G9: AB439003, G10: EU441158, G11: EU441160, and G12: JF412789. Reference sequences obtained from GenBank of T. faecale genotypes were: G1: AB066413, G2: AB439004, and G3: AB439006.

(EPS)

Clinical and microbiological data of 61 Trichosporon sp. isolates molecularly identified by sequence analysis of the IGS1 region.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Diniz P. Leite Jr. for helping with the isolation of part of the Trichosporon spp. strains, Dr. Anderson M. Rodrigues for helping with network analysis, Professor Edna Freymüller for helping with electron microscopy imaging and Marcelo H. Freire for imaging editing support.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study received funds through A.L.C. from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil (grant 2007/08575-1) and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil. I.A.I.G. received a master training fellowship from CNPq; A.C.B.P. received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil (PNPD 02640-09-0). F.C.B. received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil (2010/17179-5). R.C.H. received funds from the the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Mato Grosso (FAPEMAT). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Colombo AL, Padovan AC, Chaves GM (2011) Current knowledge of Trichosporon spp. and Trichosporonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 24: 682–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magalhaes AR, Mondino SS, Silva M, Nishikawa MM (2008) Morphological and biochemical characterization of the aetiological agents of white piedra . Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 103: 786–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Rinaldi MG, Barnes R, Hu B, et al. (2005) Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study: a 6.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of Candida and other yeast species to fluconazole and voriconazole by standardized disk diffusion testing. J Clin Microbiol 43: 5848–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Gibbs DL, Newell VA, Meis JF, et al. (2007) Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance study, 1997 to 2005: an 8.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of Candida species and other yeast species to fluconazole and voriconazole determined by CLSI standardized disk diffusion testing. J Clin Microbiol 45: 1735–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Gibbs DL, Newell VA, Bijie H, et al. (2009) Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study, 1997 to 2007: 10.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of noncandidal yeast species to fluconazole and voriconazole determined by CLSI standardized disk diffusion testing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 47: 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ando M, Suga M, Nishiura Y, Miyajima M (1995) Summer-type hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Intern Med 34: 707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sugita T, Ikeda R, Nishikawa A (2004) Analysis of Trichosporon isolates obtained from the houses of patients with summer-type hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Clin Microbiol 42: 5467–5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taj-Aldeen SJ, Al-Ansari HI, Boekhout T, Theelen B (2004) Co-isolation of Trichosporon inkin and Candida parapsilosis from a scalp white piedra case. Med Mycol 42: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, Davis A, Imaeda S, et al. (2006) White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol 55: 956–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kontoyiannis DP, Torres HA, Chagua M, Hachem R, Tarrand JJ, et al. (2004) Trichosporonosis in a tertiary care cancer center: risk factors, changing spectrum and determinants of outcome. Scand J Infect Dis 36: 564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Girmenia C, Pagano L, Martino B, D'Antonio D, Fanci R, et al. (2005) Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon species and Geotrichum capitatum in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective multicenter study from Italy and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol 43: 1818–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruan SY, Chien JY, Hsueh PR (2009) Invasive trichosporonosis caused by Trichosporon asahii and other unusual Trichosporon species at a medical center in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 49: e11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki K, Nakase K, Kyo T, Kohara T, Sugawara Y, et al. (2010) Fatal Trichosporon fungemia in patients with hematologic malignancies. Eur J Haematol 84: 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freydiere AM, Guinet R, Boiron P (2001) Yeast identification in the clinical microbiology laboratory: phenotypical methods. Med Mycol 39: 9–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sugita T, Nakajima M, Ikeda R, Matsushima T, Shinoda T (2002) Sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 regions of Trichosporon species. J Clin Microbiol 40: 1826–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmad S, Al-Mahmeed M, Khan ZU (2005) Characterization of Trichosporon species isolated from clinical specimens in Kuwait. J Med Microbiol 54: 639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karashima R, Yamakami Y, Yamagata E, Tokimatsu I, Hiramatsu K, et al. (2002) Increased release of glucuronoxylomannan antigen and induced phenotypic changes in Trichosporon asahii by repeated passage in mice. J Med Microbiol 51: 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fonseca FL, Frases S, Casadevall A, Fischman-Gompertz O, Nimrichter L, et al. (2009) Structural and functional properties of the Trichosporon asahii glucuronoxylomannan. Fungal Genet Biol 46: 496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun W, Su J, Xu S, Yan D (2012) Trichosporon asahii causing nosocomial urinary tract infections in intensive care unit patients: genotypes, virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility testing. J Med Microbiol 61: 1750–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arikan S, Hascelik G (2002) Comparison of NCCLS microdilution method and Etest in antifungal susceptibility testing of clinical Trichosporon asahii isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 43: 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paphitou NI, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Paetznick VL, Rodriguez JR, Chen E, et al. (2002) In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of Trichosporon species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46: 1144–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mekha N, Sugita T, Ikeda R, Nishikawa A, Autthateinchai R, et al. (2010) Genotyping and antifungal drug susceptibility of the pathogenic yeast Trichosporon asahii isolated from Thai patients. Mycopathologia 169: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anaissie E, Gokaslan A, Hachem R, Rubin R, Griffin G, et al. (1992) Azole therapy for trichosporonosis: clinical evaluation of eight patients, experimental therapy for murine infection, and review. Clin Infect Dis 15: 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Diaz-Guerra TM, Mellado E, Cano V, Tapia C, et al. (2005) Susceptibility patterns and molecular identification of Trichosporon species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49: 4026–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Araujo Ribeiro M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Gomez-Lopez A, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M (2008) Molecular identification and susceptibility testing of Trichosporon isolates from a Brazilian hospital. Rev Iberoam Micol 25: 221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larone DH (1995) Medically Important Fungi - A Guide to Identification. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. 274 p. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chagas-Neto TC, Chaves GM, Melo AS, Colombo AL (2009) Bloodstream infections due to Trichosporon spp.: species distribution, Trichosporon asahii genotypes determined on the basis of ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 sequencing, and antifungal susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol 47: 1074–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Santos DW, Padovan AC, Melo AS, Goncalves SS, Azevedo VR, et al. (2013) Molecular identification of melanised non-sporulating moulds: a useful tool for studying the epidemiology of phaeohyphomycosis. Mycopathologia 175: 445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O (2010) SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol 27: 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Librado P, Rozas J (2009) DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25: 1451–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16: 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jin Y, Yip HK, Samaranayake YH, Yau JY, Samaranayake LP (2003) Biofilm-forming ability of Candida albicans is unlikely to contribute to high levels of oral yeast carriage in cases of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Microbiol 41: 2961–2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Melo AS, Bizerra FC, Freymuller E, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Colombo AL (2011) Biofilm production and evaluation of antifungal susceptibility amongst clinical Candida spp. isolates, including strains of the Candida parapsilosis complex. Med Mycol 49: 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nunes JM, Bizerra FC, Ferreira RC, Colombo AL (2013) Molecular identification, antifungal susceptibility profile, and biofilm formation of clinical and environmental Rhodotorula species isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 382–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Watson KC, Kallichurum S (1970) Brain abscess due to Trichosporon cutaneum . J Med Microbiol 3: 191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Silva V, Zepeda G, Alvareda D (2003) [Nosocomial urinary infection due to Trichosporon asahii. First two cases in Chile]. Rev Iberoam Micol 20: 21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodrigues Gda S, de Faria RR, Guazzelli LS, Oliveira Fde M, Severo LC (2006) [Nosocomial infection due to Trichosporon asahii: clinical revision of 22 cases]. Rev Iberoam Micol 23: 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Walsh TJ, Groll A, Hiemenz J, Fleming R, Roilides E, et al. (2004) Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Infect 10: 44–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xia ZK, Yang RY, Wang WL, Cong L (2012) Genotyping and Antifungal Drug Susceptibility of Trichosporon asahii Isolated from Chinese Patients. Mycopathologia 173: 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tumbarello M, Fiori B, Trecarichi EM, Posteraro P, Losito AR, et al. (2012) Risk factors and outcomes of candidemia caused by biofilm-forming isolates in a tertiary care hospital. PLoS One 7: e33705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melo AS, Padovan AC, Serafim RC, Puzer L, Carmona AK, et al. (2006) The Candida albicans AAA ATPase homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rix7p (YLL034c) is essential for proper morphology, biofilm formation and activity of secreted aspartyl proteinases. Genet Mol Res 5: 664–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Martinez LR, Casadevall A (2007) Cryptococcus neoformans biofilm formation depends on surface support and carbon source and reduces fungal cell susceptibility to heat, cold, and UV light. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4592–4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dağ A, Cerikçioğlu N (2006) [Investigation of some virulence factors of Trichosporon asahii strains isolated from the clinical samples of hospitalized patients]. Mikrobiyol Bul 40: 225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hazirolan G, Canton E, Sahin S, Arikan-Akdagli S (2013) Head-to-head comparison of inhibitory and fungicidal activities of fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, and isavuconazole against clinical isolates of Trichosporon asahii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 4841–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree and genotypes of 36 T. asahii and 6 T. faecale isolates inferred by the Bayesian method. Reference sequences obtained from GenBank of T. asahii were G1: AB066386, G2: AB072606, G3: AB066397, G4: AB180191, G5: AB071387, G6: AB180192, G7: AB180194, G8: AB439002, G9: AB439003, G10: EU441158, G11: EU441160, and G12: JF412789. Reference sequences obtained from GenBank of T. faecale genotypes were: G1: AB066413, G2: AB439004, and G3: AB439006.

(EPS)

Clinical and microbiological data of 61 Trichosporon sp. isolates molecularly identified by sequence analysis of the IGS1 region.

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.