Abstract

To establish an infection, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis utilizes a plasmid-encoded type III translocon to microinject several anti-host Yop effectors into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells. YopD has been implicated in several key steps during Yop effector translocation, including maintenance of yop regulatory control and pore formation in the target cell membrane through which effectors traverse. These functions are mediated, in part, by an interaction with the cognate chaperone, LcrH. To gain insight into the complex molecular mechanisms of YopD function, we performed a systematic mutagenesis study to search for discrete functional domains. We highlighted amino acids beyond the first three N-terminal residues that are dispensable for YopD secretion and confirmed that an interaction between YopD and LcrH is essential for maintenance of yop regulatory control. In addition, discrete domains within YopD that are essential for both pore formation and translocation of Yop effectors were identified. Significantly, other domains were found to be important for effector microinjection but not for pore formation. Therefore, YopD is clearly essential for several discrete steps during efficient Yop effector translocation. Recognition of this modular YopD domain structure provides important insights into the function of YopD.

The ability to infect an animal or plant host is a feature common to many pathogens. Several of these pathogens utilize functionally homologous type III secretion systems (TTSSs) to translocate antihost effector proteins into target host cells (15, 36, 53). Pathogenic Yersinia spp. contain a ∼70-kb virulence plasmid sufficient for establishing a TTSS (23, 30, 46, 66). The type III needle complex is comprised of numerous Ysc (Yersinia secretion) components, which upon target cell contact secrete two classes of Yop proteins (Yersinia outer proteins), antihost effector proteins and proteins required for efficient translocation into target cells (14). The translocated proteins aid in bacterial colonization by subverting host cell signaling, which enables bacteria to resist phagocytosis and compromise immune surveillance (1, 17).

Induction of Yops by target cell contact (45, 49) can be mimicked in vitro by growing bacteria at 37°C in the absence of calcium (low-calcium response) (14). Regulatory control of the TTSS is established by a positive and negative control loop that involves the AraC-like activator LcrF (also termed VirF) (12, 68) and the negative regulatory element LcrQ (also termed YscM) (45, 47, 57), respectively. Type III-dependent secretion of LcrQ appears to derepress yop transcription (45, 47) through a mechanism that requires another negative regulator, YopD (65). While a ΔyopD null mutant is growth restricted at 37°C and Yop synthesis is constitutively induced in vitro (22, 65), the presence of LcrQ in the bacterial cytoplasm of a ΔyopD null mutant does not repress this constitutive Yop synthesis (65). As YopD stability is dependent on the cytosolic cognate chaperone LcrH (also termed SycD) (20, 64), it follows that a YopD-LcrH complex, which may also include LcrQ (11), is essential for maintaining yop regulatory control (2, 21). These data are consistent with the recent notion that YopD, not LcrQ, is the molecular switch that controls feedback inhibition of the TTSS (67).

In addition, secreted YopD is essential for effector translocation (22, 28, 48). Together with YopB and LcrV, YopD apparently participates in forming a pore complex in the plasma membrane through which effector translocation occurs (10, 26, 32, 41, 61). However, YopD may associate with pores only transiently, since a portion of YopD localizes to the cytosol of infected cell monolayers (22).

The observations that support the hypothesis that YopD plays a role at several steps of the translocation process are intriguing. However, it is difficult to conceptualize how YopD actually integrates these multiple activities. As there are homologues of this protein in other TTSSs (6, 8, 36), understanding the mechanism of YopD function would significantly increase our understanding of type III secretion. Until now, this has been impeded by the inability to investigate the functions of YopD in isolation from each other. In this study, we systematically mutagenized YopD. Analyses of the mutants verified that YopD is a multifunctional protein involved in several key steps that are necessary for efficient Yop effector translocation. In particular, discrete functional domains were isolated that enabled the role of YopD in translocation to be separated from its role in pore formation and regulation. The mosaic-like structure of YopD is likely to facilitate coordination of the multiple functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Unless indicated otherwise, bacteria were routinely cultivated in Luria-Bertani agar or broth at either 26°C (Yersinia pseudotuberculosis) or 37°C (Escherichia coli) with aeration. When required, appropriate antibiotics were added at the following final concentrations: carbenicillin, 100 μg per ml; kanamycin, 50 μg per ml; gentamicin, 20 μg per ml; spectinomycin, 20 μg per ml; and chloramphenicol, 25 μg per ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ (lacZYA-argF)U169 | Stratagene |

| TOPO | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC), φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 (Δara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Smr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| S 17-1λpir | recA thi pro hsdR M+ <RP4:2-Tc:Mu:Km:Tn7>Tpr Smr | 55 |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis strains | ||

| YPIII/pIB102 | yadA::Tn5, Kmr (wild type) | 7 |

| YPIII/pIB621 | pIB102, yopD in-frame full-length deletion of codons 4 to 303, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB625 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 4 to 20, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB605 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 23 to 47, Kmr | 24 |

| YPIII/pIB626 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 53 to 68, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB627 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 73 to 90, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB628 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 95 to 117, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB623 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 128 to 149, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB629 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 150 to 170, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB630 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 174 to 198, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB631 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 207 to 227, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB632 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 234 to 254, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB633 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 256 to 275, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB622 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 278 to 292, Kmr | 22 |

| YPIII/pIB624 | pIB102, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 293 to 305, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522 | pIB102, yopE, yerA in-frame deletions, Kmr | 19 |

| YPIII/pIB522625 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 4 to 20, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522605 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 23 to 47, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522626 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 53 to 68, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522627 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 73 to 90, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522628 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 95 to 117, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522623 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 128 to 149, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522629 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 150 to 170, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522630 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 174 to 198, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522631 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 207 to 227, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522632 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 234 to 254, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522633 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 256 to 275, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522622 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 278 to 292, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB522624 | pIB522, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 293 to 305, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155 | pIB102, complete yopK deletion, Kmr | 33 |

| YPIII/pIB155D | pIB155, yopD in-frame full-length deletion of codons 4 to 303, Kmr | 22 |

| YPIII/pIB155625 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 4 to 20, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155605 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 23 to 47, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155626 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 53 to 68, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155627 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 73 to 90, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155628 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 95 to 117, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155623 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 128 to 149, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155629 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 150 to 170, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155630 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 174 to 198, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155631 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 207 to 227, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155632 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 234 to 254, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155633 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 256 to 275, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155622 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 278 to 292, Kmr | 22 |

| YPIII/pIB155624 | pIB155, yopD in-frame deletion of codons 293 to 305, Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155625I288K | pIB155, containing YopD(Δ4-20, 1288K), Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155605I288K | pIB155, containing YopD(Δ23-47, 1288K), Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155626I288K | pIB155, containing YopD(Δ53-68, 1288K), Kmr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB15562211 | pIB155, containing YopD(1288K), Kmr | Unpublished data |

| YPIII/pIB75 | pIB102, yscU in-frame deletion of codons 25 to 329, Kmr | 37 |

| YPIII/pIB26 | pIB102, lcrQ in-frame deletion, Kmr Spr/Smr | 45 |

| YPIII/pIB1556257526 | pIB155625, containing in-frame deletions of yscU and lcrQ, Kmr Spr/Smr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB1556057526 | pIB155605, containing in-frame deletions of yscU and lcrQ, Kmr Spr/Smr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB1556267526 | pIB155626, containing in-frame deletions of yscU and lcrQ, Kmr Spr/Smr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB155D7526 | pIB155D, containing in-frame deletions of yscU and lcrQ, Kmr Spr/Smr | This study |

| YPIII/pIB1557526 | pIB155, containing in-frame deletions of yscU and lcrQ, Kmr Spr/Smr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR 4-TOPO | TA cloning vector, Kmr Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pDM4 | sacBR, Cmr | 40 |

| pMF443 | pDM4 containing an 810-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ4-20, Cmr | This study |

| pMF514 | pDM4 containing a 780-bp Xhol/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ23-47, Cmr | This study |

| pMF444 | pDM4 containing an 810-bp Xhol/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ53-68, Cmr | This study |

| pMF445 | pDM4 containing a 720-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ73-90, Cmr | This study |

| pMF446 | pDM4 containing a 770-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ95-117, Cmr | This study |

| pMF107 | pDM4 containing a 400-bp SpeI-XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ128-149, Cmr | This study |

| pMF447 | pDM4 containing a 780-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ150-170, Cmr | This study |

| pMF448 | pDM4 containing a 760-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ174-198, Cmr | This study |

| pMF449 | pDM4 containing a 770-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ207-227, Cmr | This study |

| pMF450 | pDM4 containing an 860-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ234-254, Cmr | This study |

| pMF451 | pDM4 containing an 870-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ256-275, Cmr | This study |

| pMF088 | pDM4 containing a 292-bp SpeI-XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ278-292, Cmr | 22 |

| pMF108 | pDM4 containing a 500-bp SpeI-XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopDΔ293-305, Cmr | This study |

| pMF471 | pDM4 containing a 960-bp XhoI/XbaI PCR fragment of the allele encoding YopD1288K, Cmr | Unpublished data |

| pLS13 | pDM4 containing a 669-bp PCR fragment of the allele encoding YscUΔ25-329, Cmr | 37 |

| pRN53 | pDM4 mutagenesis plasmid in which the entire lcrQ allele is replaced by an Sp/Sm resistance gene, Cmr Spr/Smr | 45 |

| pTS103-Gm | orf1 and exoS cloned into pUC19, Gmr Amps | 10 |

Recombinant DNA techniques, enzymes, and reagents.

Chemical transformation in E. coli was performed by the method of Hanahan (27). Plasmid DNA was purified from E. coli with a Quantum Prep miniprep kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories AB, Sundbyberg, Sweden) or with a Jetstar 2.0 plasmid midi kit (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany) as described by the manufacturer. Standard DNA manipulation techniques were performed essentially as described elsewhere (51). DNA fragments were recovered from agarose by spin column purification performed as described by the manufacturer (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). All modifying enzymes were purchased from either Roche Diagnostics Scandinavia (Bromma, Sweden) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). The DyNAzyme EXT DNA polymerase used for PCR amplification was purchased from Finnzymes (Espoo, Finland), oligonucleotides were purchased from DNA Technology A/S (Aarhus, Denmark), and deoxynucleoside triphosphates were purchased from Amersham Biosciences Europe GmbH (Uppsala, Sweden).

Construction of sequential in-frame ΔyopD deletion mutants.

Amplified DNA fragments used for constructing the in-frame deletion mutations were generated by overlapping PCR (35). The primer combinations used to create the in-frame yopD deletion mutants are listed in Table 2. Each fragment containing a sequence flanking the specific yopD deletion was confirmed by sequence analysis by using a DYEnamic ET terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences); this was facilitated by initial cloning into the pCR4-TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The fragments were then cloned into XhoI- (or SpeI-) and XbaI-digested suicide mutagenesis vector pDM4 (40). E. coli S17-1λpir was used as the donor strain in conjugal mating experiments with Y. pseudotuberculosis. For selection for the appropriate allelic exchange events we used established methods (40).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used for construction of ΔyopD deletions

| YopD deletiona | Oligonucleotide pairsb |

|---|---|

| Δ1 (4-20) | pXhoA (5′-TTG AAC ACT CGA GAC ATG GCA GCG TTA-3′) and 1B (5′-TAT TGT CAT GGT TAT TCC TCC-3′) |

| 1C (5′-ATA ACC ATG ACA ATA ATC ACT ACA GAG ACA GTC-3′) and pXbaD3 (5′-ATG CCA GTC TAG ATT GAT CCG CTA CCT-3′) | |

| Δ3 (53-68) | pXhoA and 2B (5′-TAA GCT TGC CTC GCT ACT CTT-3′) |

| 2C (5′-AGC GAG GCA AGC TTA GTT GCA TTA CTG AGT-3′) and pXbaD3 | |

| Δ4 (73-90) | pXhoA and 3B (5′-CAG TAA TGC AAC ATT GAT TCC-3′) |

| 3C (5′-AAT GTT GCA TTA CTG GAA CTG GCA CGT AA-3′) and pXbaD3 | |

| Δ5 (95-117) | pXhoA and 4B (5′-ACG TGC CAG TTC CAA CAG CA-3′) |

| 4C (5′-TTG GAA CTG GCA CGT CAG GTA GCG GAG ATG-3′) and pXbaD3 | |

| Δ6 (128-149) | pSpeA2 (5′-CGG TCA CTA GTG CCA GAA TTG ATC-3′) and pB2 (5′-TTT TGC ACC GCT GAC CAT CTC-3′) |

| pC2 (5′-GTC AGC GGT GCA AAA TCT ATA GCG AAA GAG GTG AA-3′) and pXbaD2 (5′-TTG GCT CTA GAG TCG GTC ATT CTG-3′) | |

| Δ7 (150-170) | pXhoA1 (5′-CCA GGG ACT CGA GGT TGC ATT ACT GAG-3′) and 5B (5′-AAA AGC ACT AGC AAC CGT AGA A-3′) |

| 5C (5′-GTT GCT AGT GCT TTT CGC GAA CAA CTT ATT-3′) and pXbaD1 (5′-CAC AAC TCT AGA TTA ACT AAT AT-3′) | |

| Δ8 (174-198) | pXhoA1 and 6B (5′-TTG TTC GCG GCC AGC AAT AT-3′) |

| 6C (5′-CTG GCC GCG AAC AAT GGA AAC CAG AGC AG-3′) and pXbaD1 | |

| Δ9 (207-227) | pXhoA1 and 7B (5′-ATC CGC TAC CTG CTC TGG TT-3′) |

| 7C (5′-GAG CAG GTA GCG GAT AAT GCC GCA ACG CAG-3′) and pXbaD1 | |

| Δ10 (234-254) | pXhoA1 and 8B (5′-CGG CTG CGT TGC GGC ATT AA-3′) |

| 8C (5′-GCC GCA ACG CAG CCG GAG AAA GAA GTC AAT GCA-3′) and pXbaD (5′-CTC AGG TCT AGA GCT ACT ACA TG-3′) | |

| Δ11 (256-275) | pXhoA1 and 9B (5′-CTC TTT GAC CTC GGC TTG AGA ATA-3′) |

| 9C (5′-GCC GAG GTC AAA GAG TAT AAT GAT AAC TT-3′) and pXbaD | |

| Δ13 (293-305) | pSpeA1 (5′-TGG AAA CTA GTG CAG GTA GCG GAT-3′) and pB3 (5′-AAC ATA TTG TTC AAT CAA GCG-3′) |

| pC3 (5′-ATT GAA CAA TAT GTT TGA CCA TTG ATG ACC TTG-3′) and pXbaD |

The numbers in parentheses indicate the internal amino acids deleted from YopD (306 amino acids). Details concerning the construction of Δ2 have been described previously (24).

Boldface type indicates the incorporated XhoI, SpeI, and XbaI restriction sites used for cloning of the PCR amplified DNA fragments. Underlining indicates the complementary overlap between the corresponding B and C primers. The oligonucleotides used for construction of Δ12 (278-292) have been described elsewhere (22).

Protein stability.

Protein stability in the presence of endogenous proteases was analyzed after growth in defined TMH medium as described previously (20). In parallel, intrabacterial protein stability was also assessed by the method of Feldman and colleagues (18) for translocation-deficient ΔyopD mutant alleles only. Protein fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Scheicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany) by using a Hoefer SemiPhor semidry transfer unit (Amersham Biosciences). Membrane-bound YopD was detected by using rabbit anti-YopD polyclonal antiserum, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) prior to detection with the enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL) used as directed by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences).

Limited chymotrypsin digestion.

Overnight cultures of translocation-deficient YopD mutants were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.2 in 10 ml of fresh culture medium (Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2). Bacteria were grown for 1 h at 26°C and then incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged at 2,500 × g, and the supernatants containing secreted proteins were collected and passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size sterile filter. CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 20 mM, and the tubes were placed on ice for 20 min. Each sample was divided into two 5-ml portions by transfer into new tubes. To one tube, chymotrypsin (Roche Diagnostics) was added to a final concentration of 10 μg per ml, while the other tube was treated as a control for spontaneous proteolysis. The tubes were incubated on ice for 30 min, and then proteinase activity was quenched and proteins were precipitated on ice for 1 h by addition of 0.1 volume of trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation for 10 min at 2,500 × g, the supernatants were carefully removed by aspiration. Each remaining precipitate was dissolved in 50 μl of 2× protein sample buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 0.001% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol, 2% β-mercaptoethanol) and fractionated by SDS-PAGE by using 15% Tris-Tricine gels. Standard immunoblotting procedures were used to detect YopD peptides with polyclonal rabbit anti-YopD antiserum.

Growth phenotypes and the MOX test.

Yersinia plating frequencies and the subsequent growth phenotypes when the organisms were grown under high- and low-Ca2+ conditions at 37°C were determined by using the MOX test (5, 23). Briefly, wild-type Yersinia (YPIII/pIB102) was unable to grow on LA (Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 2% agar) supplemented with magnesium oxalate (in the absence of Ca2+) at 37°C, and normal growth occurred on LA with 2.5 mM CaCl2; this phenotype was termed calcium dependent (CD). The ΔyopD null mutant (YPIII/pIB621) was unable to grow at 37°C irrespective of the Ca2+ level (temperature sensitive [TS] phenotype). For confirmation, we performed parallel experiments in which the growth phenotypes were determined at 37°C during logarithmic growth of bacteria in liquid TMH medium (lacking Ca2+) or medium supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2 (21).

Analysis of Yop synthesis and secretion.

Yop synthesis and secretion were induced as previously described (20-22). Briefly, total Yop levels were assessed by obtaining samples directly from the bacterial culture suspension, which contained a mixture of Yops secreted into the culture medium and Yops in intact bacteria. Samples of the cleared supernatant that contained only Yops secreted into the culture medium were obtained to assess protein secretion levels. All protein fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and then subjected to immunoblotting. Specific proteins were detected on the membrane support by using rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against YopH, YopB, LcrV, YopD, and YopE.

Cultivation and infection of HeLa cells.

Cultivation and infection of HeLa cells for cytotoxicity assays were performed by using standard methods (22). The infection period was 5 h long, and at 1- h intervals the extent of morphological change was visualized by light microscopy. The degrees of HeLa cell cytotoxicity induced by Yersinia strains expressing mutant yopD derivatives were recorded by using a sliding scale. The cytotoxicity induced by wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis (YPIII/pIB102) defined the upper limit, while the cytotoxicity induced by the ΔyopD null mutant (YPIII/pIB621) defined the lower limit.

Ras modification assay.

Y. pseudotuberculosis strains expressing ExoS from the high-copy-number vector pTS103-Gm were tested for the ability to induce ExoS-mediated modification of eukaryotic Ras in infected HeLa cells (59). Modification of Ras was visualized by Western blotting with Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) coupled to the use of an ECL+plus Western blot detection system (Amersham Biosciences) and an anti-Ras monoclonal antibody (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Ky.).

Contact hemolysis of sheep erythrocytes.

The contact hemolysis assay in the presence or absence of the carbohydrates raffinose, dextrin 15, and dextran 4 was performed as previously described (10, 26, 33).

RESULTS

Generation and elemental characterization of sequential yopD mutants of Y. pseudotuberculosis.

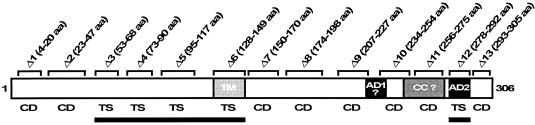

By using sequential deletional mutagenesis it has recently been demonstrated that YopD has two separate LcrH-binding sites, one at positions 53 to 149 and one at positions 278 to 292 (Fig. 1) (20). To further investigate the presence of discrete YopD functional domains, these internal deletions were introduced in cis by allelic exchange onto the virulence plasmid of Y. pseudotuberculosis wild-type strain YPIII/pIB102 (Fig. 1). We first examined the stability of the new mutants using an assay that detected their susceptibility to endogenous proteases (20). Significantly, the wild-type and mutant proteins remained resistant to proteolysis (data not shown). We interpreted this to indicate that the native structure of the YopD variants was preserved.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the 306-amino-acid YopD protein of pathogenic Yersinia spp. The structural features of YopD include the putative transmembrane domain (TM) predicted by using the TMPRED web server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html). Two amphipathic α-helices, one located internally (AD1) and the other a biologically relevant domain at the C terminus (AD2) (22, 62), were both identified by helical wheel projection (Antheprot, version 3.2; G. Deleage, Lyon, France). A predicted coiled coil region (CC) was identified by using the COILS web server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html). A question mark indicates a domain that was predicted only when low-stringency parameters were used. Also shown are the locations of the following in-frame sequential ΔYopD deletions used in this study: Δ1, YPIII/pIB625 (Δ4-20 aa [deletion of amino acids 4 to 20]); Δ2, YPIII/pIB605 (Δ23-47 aa); Δ3, YPIII/pIB626 (Δ53-68 aa); Δ4, YPIII/pIB627 (Δ73-90 aa); Δ5, YPIII/pIB628 (Δ95-117 aa); Δ6, YPIII/pIB623 (Δ128-149 aa); Δ7, YPIII/pIB629 (Δ150-170 aa); Δ8, YPIII/pIB630 (Δ174-198 aa); Δ9, YPIII/pIB631 (Δ207-227 aa); Δ10, YPIII/pIB632 (Δ234-254 aa); Δ11, YPIII/pIB633 (Δ256-275 aa); Δ12, YPIII/pIB622 (Δ278-292 aa); and Δ13, YPIII/pIB624 (Δ293-305 aa). The regulatory status of individual mutants, as determined by MOX analysis (5, 23) (see Materials and Methods), is indicated. CD reflects wild-type regulatory control of Yop synthesis, and TS reflects defective regulatory control in which Yop synthesis is constitutive. YopD domains important for regulatory control (indicated by a solid line) correspond to identical domains required for binding the dedicated chaperone LcrH (20, 21).

A ΔyopD null mutant lacked yop regulatory control that permitted constitutive Yop synthesis at 37°C, even during growth in noninductive media, and it was concomitantly growth restricted at elevated temperatures irrespective of the Ca2+ level (TS phenotype) (5, 22, 65). This phenotype is distinct from the growth phenotype of wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis, which requires Ca2+ for growth at 37°C (CD phenotype) and exhibits a normal pattern of Yop synthesis (5, 22, 65). We used a MOX test (5, 23) to analyze the regulatory status of each YopD deletion strain. As expected, a CD phenotype was obtained with Y. pseudotuberculosis wild-type strain YPIII/pIB102 (data not shown). Furthermore, YopD deletion mutants Δ1, Δ2, Δ7 to Δ11, and Δ13 had an equivalent CD phenotype (Fig. 1). On the other hand, YopD deletion mutants Δ3 to Δ6 and Δ12, which lacked essential domains required for LcrH binding (20), had a TS phenotype, being unable to form colonies at 37°C; this is comparable to the growth restriction observed for a ΔyopD null mutant (Fig. 1). In parallel, we confirmed by immunoblotting that the TS mutants were also derepressed for Yop synthesis (data not shown). Taken together, these findings show that YopD-dependent yop regulatory control requires a YopD-LcrH complex, which is consistent with previous reports (2, 9, 21).

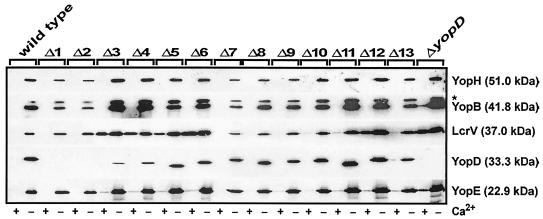

We next investigated the secretion efficiency of each YopD variant and the effect on secretion of other essential type III substrates. Secreted proteins from cleared culture supernatants of bacteria grown both in the absence of Ca2+ (brain heart infusion [BHI] broth supplemented with 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2 [inductive conditions]) and in the presence of Ca2+ (BHI broth supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2 [repressive conditions]) were analyzed. We observed efficient YopD secretion from mutants Δ5 to Δ13 and impaired YopD secretion from mutants Δ3 and Δ4 during growth in secretion-competent medium (without Ca2+) (Fig. 2). On the other hand, secretion by mutants Δ1 and Δ2, although adequately expressed (data not shown), was not detected under these assay conditions (Fig. 2). This observation showed that the N-terminal 47 residues are important for efficient YopD secretion. Significantly, other type III substrates (translocators [YopB and LcrV] and effectors [YopE and YopH]) were generally secreted at normal wild-type levels (Fig. 2), although more secretion was typically observed for YopD mutants lacking yop regulatory control (null mutant and mutants Δ3 to Δ6 and Δ12). In addition, the same mutants specifically secreted LcrV in noninducing media (with Ca2+) (Fig. 2), a phenomenon reported previously for mutants with mutations in both YopD (65) and its cognate chaperone, LcrH (21, 56).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of Yop secretion from Y. pseudotuberculosis strains grown in BHI broth either with (+) or without (−) Ca2+. Secreted Yops (a mixture of Yops present only in cleared culture supernatants) were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by immunoblot analysis by using polyclonal rabbit anti-YopH, anti-YopB, anti-LcrV, anti-YopD, and anti-YopE antisera. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific cross-reactive band detected by using anti-YopB antiserum. The molecular masses indicated in parentheses were deduced from the primary sequences.

Identification of discrete YopD domains essential for Yop effector translocation.

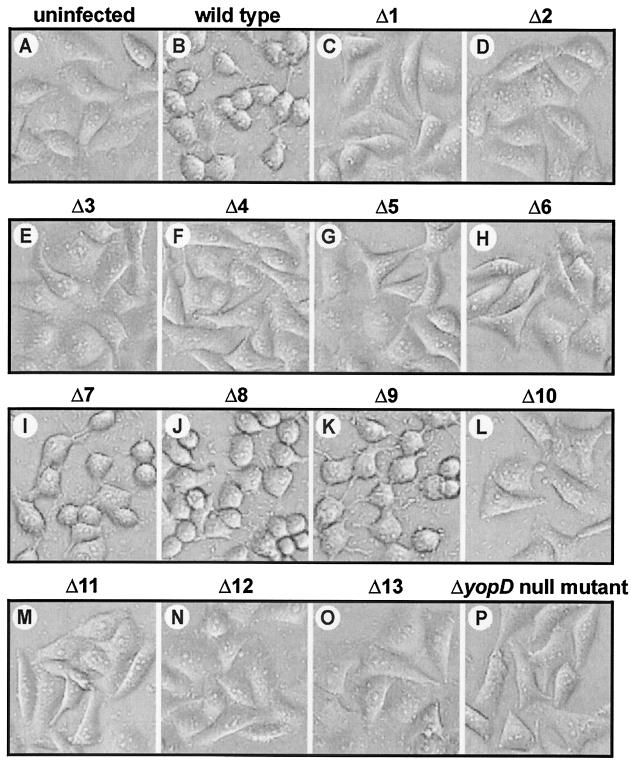

Having defined the secretion effects imposed by the various yopD mutations, we tried to identify discrete translocation domains. A yopD null mutant does not translocate the YopE Rho-GAP cytotoxin or the YopH tyrosine phosphatase into infected HeLa cell monolayers (22). To investigate if a particular region of YopD was involved in the translocation, we initially used the YopE-dependent HeLa cell cytotoxicity assay (48) to determine translocation competency. As expected, nonsecreted YopD mutants Δ1 and Δ2 and the yopD null mutant did not translocate YopE, as the cellular morphology of infected monolayers was indistinguishable from that of uninfected cell monolayers (Fig. 3, compare panels C and D with panel A). Similarly, YopD mutants Δ3 to Δ6 and Δ10 to Δ13 also did not induce YopE-dependent cytotoxicity towards HeLa cells (Fig. 3E to H and L to O). In fact, only YopD mutants Δ7 to Δ9 were indistinguishable from the wild type in terms of being able to efficiently translocate YopE into target cells (Fig. 3, compare panels I to K with panel B).

FIG. 3.

Infection of HeLa cells by Y. pseudotuberculosis. Strains were allowed to infect a monolayer of growing HeLa cells, and at 2 h postinfection the effect of the bacteria on the HeLa cells was determined by phase-contrast microscopy. Note the extensive rounding of the YopE-dependent cytotoxically affected HeLa cells (B and I to K). HeLa cells infected with strains carrying a yopD null mutation or the in-frame Δ1 to Δ6 and Δ10 to Δ13 YopD deletions had normal uninfected cell morphology (compare panel A with panels C to H and L to P). Prolonged infections (up to 5 h) did not alter the experimental outcome (data not shown).

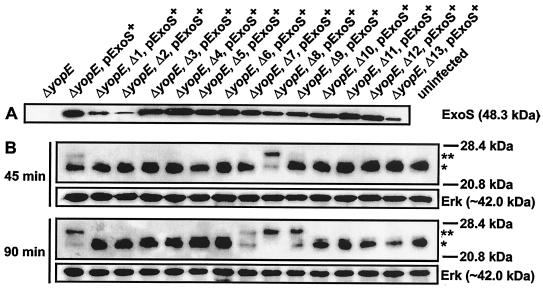

In parallel, we introduced the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS effector molecule (pTS103-Gm) (10) into the Yersinia ΔyopE null mutant (YPIII/pIB522) (19) that also contained a variant of YopD (Δ1 to Δ13). Because there is an ADP-ribosylating domain that relies on the eukaryotic 14-3-3 protein family (4, 31), ExoS-dependent ADP ribosylation of cytoplasmic proteins, such as Ras, provides a sensitive method for detecting direct translocation of ExoS into target cells (10, 31, 59, 60). A YopE defective background was chosen to avoid an inhibitory effect on pore formation (63) that may have had an impact on the ExoS translocation efficiency. We confirmed that ExoS encoded on plasmid pTS103-Gm was efficiently secreted from all strains, except when it was combined with the Δ1, Δ2, and Δ13 in-frame deletions of YopD (Fig. 4A). At least for the Δ1 and Δ2 backgrounds, this phenomenon was also observed for Yop secretion (Fig. 2). The ExoS-producing strains were then used to infect HeLa cell monolayers. Cytoplasmic Ras in infected HeLa cell lysates was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with monoclonal anti-Ras antibodies. ExoS-dependent ADP ribosylation of Ras is easily observed as a more slowly migrating band after fractionation (10, 31, 59, 60). Similar to their inability to translocate YopE, YopD deletion mutants Δ1 to Δ6 and Δ10 to Δ13 did not translocate ExoS, as Ras remained unmodified even after 135 min of infection, similar to the results obtained for the uninfected control (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Significantly, strains harboring the wild-type YopD (ΔyopE) and the Δ7 to Δ9 variants were all able to translocate ExoS, yet distinct differences in translocation efficiency were detected. Interestingly, the Δ8 mutant translocated ExoS at a higher rate than the parental strain, as judged by the more rapid disappearance of unmodified Ras. On the other hand, the rate of translocation by the Δ7 mutant was notably lower, while the rate of translocation by the Δ9 mutant was intermediate, despite the fact that both organisms were able to rapidly induce YopE-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. 3 and 4). This further established the utility of the ExoS reporter system as an important tool in establishing the efficiency of effector translocation.

FIG. 4.

(A) Analysis of secreted ExoS produced in trans by a ΔyopE null mutant (YPIII/pIB522) of Y. pseudotuberculosis harboring sequential deletions of YopD and grown under inducing conditions (without Ca2+). Secreted protein from cleared bacterial supernatants was separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by immunoblot analysis by using polyclonal rabbit anti-ExoS antisera. ExoS, together with its dedicated chaperone Orf1, is encoded on the high-copy-number plasmid pTS103-Gm (pExoS+) under control of the native promoter (10). (B) Ras modification in HeLa cells infected with bacteria expressing ExoS. HeLa cells were harvested after infection at 45 and 90 min and dissolved in sample buffer. Proteins in the HeLa cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and this was followed by immunoblotting with anti-Ras monoclonal antibody. As a loading control, the same filters were also probed with a monoclonal antibody directed against the eukaryotic cytosolic marker protein Erk. One asterisk indicates the position of unmodified Ras, while two asterisks indicate the position of the more slowly migrating modified version of Ras. No further Ras modification was observed at later times (data not shown).

The data described above highlight regions of YopD (regions in Δ7 to Δ9, encompassing residues 150 to 227) that are dispensable for translocation. Furthermore, in the secreted YopD mutants, residues 53 to 149 (in Δ3 to Δ6) and the C terminus extending from residue 234 (in Δ10 to Δ13) are required for Yop effector translocation. Despite this translocation defect, the mutants with deletions encompassing residues 234 to 275 (Δ10 and Δ11) and the extreme C terminus from residue 293 (Δ13) all exhibit normal yop regulatory control. This finding revealed novel YopD domains that are involved solely in effector translocation.

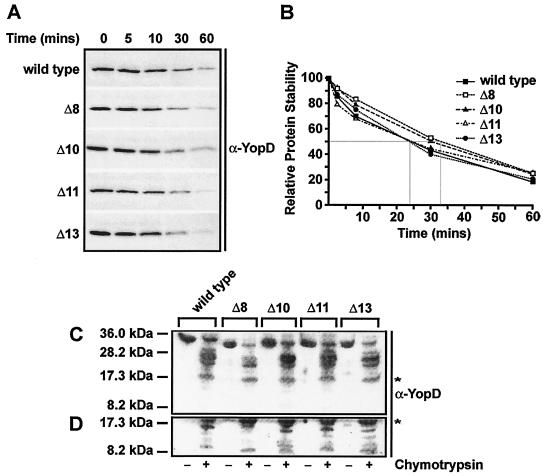

Examination of the intrabacterial stability of YopD.

Identification of YopD mutants Δ10, Δ11, and Δ13, which are defective only in translocation, was an important finding. Therefore, we examined the stability of these three mutants to ensure that the phenotypic readout was not due to the in-frame deletions imparting a conformation biased toward one experimental assay over another. We used an intrabacterial stability assay (18) as a means to quantitate the native folding propensity of these mutants. We did not detect any significant differences in the susceptibilities of the wild-type and mutant proteins to endogenous proteases over a 60-min period (Fig. 5A). This was true for either the Δ8 mutant, which was phenotypically indistinguishable from the wild type, or mutants Δ10, Δ11, and Δ13, which exhibited a defect in Yop effector translocation but not in regulation. This was reflected by the similar half-lives (range, 24 to 33 min) of all the variants tested (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Conformational analysis of YopD internal deletion mutants. (A and B) Intrabacterial stability of YopD proteins produced by Y. pseudotuberculosis grown at 37°C in the presence of 5 mM CaCl2. At time zero, chloramphenicol was added in order to stop new protein synthesis. Aliquots were taken at different times, and the amounts of proteins were determined by Western blot analysis (A) and by a densitometry analysis in which images were first acquired with a Fluor-S MultiImager (Bio-Rad) and after inversion the intensity of each band was quantified by using the Quantity One quantitation software (version 4.2.3; Bio-Rad) (B). (C and D) Immunoblots of secreted YopD prepared from cleared culture supernatants that had been incubated with (+) or without (−) chymotrypsin for 30 min prior to trichloroacetic acid precipitation. YopD was identified by using polyclonal rabbit anti-YopD antiserum (α-YopD) in combination with enhanced chemiluminescence detection prior to normal exposure (A and C) and overexposure (D) to X-ray film. For reference, the asterisk identifies identical bands in panels C and D.

We also used chymotrypsin digestion of secreted YopD to further probe for structural differences between the wild-type and mutant proteins. Notable differences in protein digestion patterns would have been indicative of altered protein folds. Chymotrypsin was used because it was predicted to target about five recognition sites in YopD with a cleavage probability of ≤80%, as determined with the PeptideCutter web server (http://us.expasy.org/tools/peptidecutter) (data not shown), which resulted in an even distribution of peptide fragments in the size range from approximately 8 to 32 kDa. Significantly, YopD variants secreted from Yersinia all exhibited very similar peptide fragmentation patterns in the suggested size range (Fig. 5C and D). Small deviations likely occurred because each in-frame deletion was predicted to remove at least one chymotrypsin recognition site.

Taken together, these results supported the conclusion that the YopD variants encoded by the Δ10, Δ11, and Δ13 mutant alleles had comparable tertiary structures. This conclusion was also supported by the ability of the mutants to still bind LcrH (20), a prerequisite for yop regulatory control (21). We interpreted this to indicate that the loss of Yop effector translocation, but not the loss of yop regulatory control, in these YopD mutant backgrounds is a bona fide phenotype.

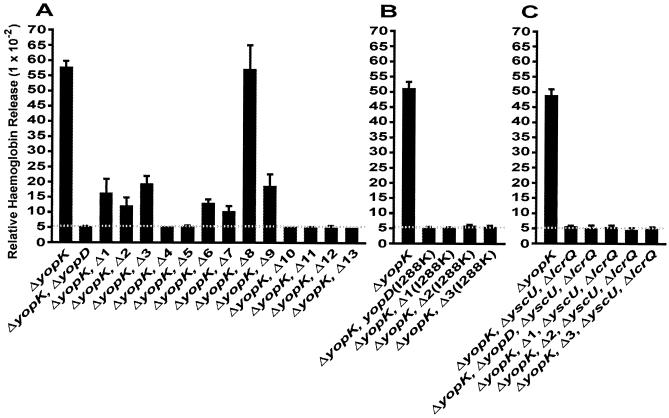

Contact hemolysis as a prelude to Yop effector translocation.

A number of studies have implicated YopD in a tripartite complex with the other translocator proteins LcrV and YopB, which forms pores in the eukaryotic membrane through which Yop effectors are translocated (10, 32, 41, 61). Therefore, we wanted to investigate whether the participation of YopD in pore formation always ensures functional Yop translocation. Workers in our laboratories routinely use hemoglobin release from erythrocytes infected with Yersinia as a measure of pore formation in eukaryotic membranes (10, 26, 32, 33). All the yopD deletion alleles were introduced into the ΔyopK null mutant (YPIII/pIB155) (34), since this background enhances the assay sensitivity (10, 26, 32). As anticipated, YopD mutants Δ7, Δ8, and Δ9 were able to lyse erythrocytes (Fig. 6A), which paralleled the capacity of the mutants to translocate antihost effectors into target cells (Fig. 3 and 4). Indeed, lysis by the Δ8 mutant was comparable to lysis by the parental YPIII/pIB155 strain producing wild-type YopD. On the other hand, not only were mutants Δ4, Δ5, and Δ10 to Δ13 unable to translocate Yop effectors, they were also not capable of lysing erythrocyte membranes, which is comparable to the results obtained for the control strain harboring a full-length deletion of yopD (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, however, lysis was still observed for mutants Δ1 to Δ3 and Δ6 (Fig. 6A), even though these mutants displayed no evidence of effector translocation (Fig. 3 and 4). It is noteworthy that the degree of lysis was no different than the degree of lysis that we observed for mutants Δ7 and Δ9, which could translocate YopE and ExoS.

FIG. 6.

Lysis of erythrocytes by a ΔyopK null mutant (YPIII/pIB155) of Y. pseudotuberculosis also having a sequential in-frame deletion of YopD (A) in combination with the site mutation I288K located in the C-terminal amphipathic α-helix (B) or with a defective type III secretion apparatus (ΔyscU ΔlcrQ) (C). Sheep erythrocytes were infected with the different strains of Y. pseudotuberculosis for 3 h. After this the amount of released hemoglobin was determined spectrophotometrically. The values are the average lytic activities ± standard deviations (as determined with Microsoft Excel 2000) for at least four individual experiments performed in quadruplicate.

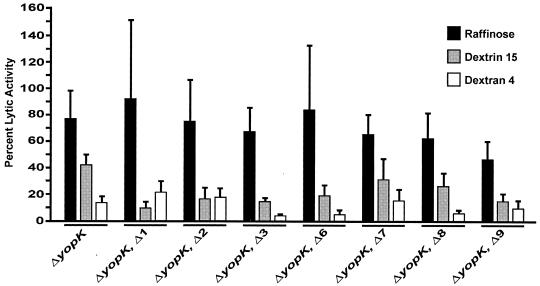

To confirm that the observed lytic activities of wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis and isogenic YopD mutants Δ1 to Δ3 and Δ6 to Δ9 were actually due to the ordered membrane insertion of YopD-dependent pores having similar dimensions, we performed an osmoprotection assay. Osmoprotectants of suitable sizes can prevent osmotic lysis of erythrocytes (10, 32). After infection of sheep erythrocytes, the largest carbohydrate, dextran 4 (diameter, 3 to 3.5 nm), and the medium-size carbohydrate, dextrin 15 (diameter, 2.2 nm), dramatically inhibited this activity in a manner that was typically size dependent (Fig. 7). Moreover, the smallest carbohydrate, raffinose (diameter, 1.2 to 1.4 nm), generally poorly prevented hemoglobin release except with mutant Δ9, in which there was a >50% reduction in hemolysis. Nevertheless, the overall pattern of osmoprotection observed for the specific YopD mutants was comparable to the wild-type pattern, which clearly demonstrated that the lytic activity was due to the specific formation of YopD-dependent pores that were of similar sizes in erythrocyte membranes and not due to nonspecific membrane disruption. Significantly, this assay also confirmed that the Δ3 and Δ6 mutant proteins were able to form pores that resembled those formed by wild-type YopD yet were not sufficient for effector microinjection. Hence, YopD-dependent pore formation does not guarantee functional translocation. This strongly supports the hypothesis that there is a multistep process during translocation and that pore formation is only one discrete part of this process. Thus, YopD appears to play an important role in more than one step of the translocation process.

FIG. 7.

Osmoprotection of infected erythrocytes by different carbohydrates. Sheep erythrocytes were infected with the different strains of Y. pseudotuberculosis for 3 h in the presence of carbohydrates having different diameters, including raffinose (diameter, 1.2 to 1.4 nm), dextrin 15 (diameter, 2.2 nm), and dextran 4 (diameter, 3 to 3.5 nm), after which the amounts of released hemoglobin were determined spectrophotometrically. The lytic activity is expressed as a percentage of the lysis in the absence of sugars. The bars and error bars indicate the means and standard errors of the means (as calculated by using Mathsoft Axum software, version 7.0), respectively, for three independent experiments.

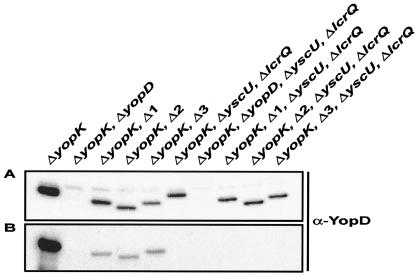

Even though the mutant Δ1 and Δ2 proteins were apparently not secreted at detectable levels (Fig. 2), it is intriguing that they could form pores with sizes similar to the size of wild-type pores in erythrocyte membranes (Fig. 7). Therefore, to further examine this finding, into these YopD variants we introduced a second-site mutation (I288K) in the C-terminal amphipathic α-helix that is known to eliminate pore formation (Olsson and Francis, unpublished data). Significantly, the double YopD mutants were no longer able to form pores in erythrocyte membranes (Fig. 6B), which reinforces the idea that the pore-forming ability of the Δ1 and Δ2 mutant proteins is dependent on secreted forms of YopDΔ4-20 and YopDΔ23-47, respectively. Since this suggests that these variants are actually secreted, albeit at very low levels, we sought to clarify this issue. The YscU inner membrane protein is essential for type III secretion (37). Therefore, we introduced a ΔyscU deletion into Δ1 and Δ2 mutants that also contained a ΔyopK deletion. However, as a loss-of-function mutation in the TTSS represses Yop synthesis (14), we restored Yop synthesis by introducing a deletion into the LcrQ repressor element (45, 47, 57). The new mutants were compared to their isogenic parents for the ability to secrete YopD and the ability to form pores in erythrocyte membranes. Clearly, the ΔyopK Δ1 and ΔyopK Δ2 mutants could indeed secrete minor amounts of YopDΔ4-20 and YopDΔ23-47, respectively, but the secretion was visualized only after fivefold more protein was fractionated by SDS-PAGE (compared to the amounts in experiments whose results are shown in Fig. 2) and after overexposure of the ECL-detected membrane to X-ray film (Fig. 8). This secretion was type III dependent because the quadruple mutants (having deletions in yopK, yscU, lcrQ, and yopD) did not secrete detectable levels of either YopD variant (Fig. 8). Moreover, these nonsecreting mutants were not able to induce pore formation in our hemoglobin release assay (Fig. 6C). Thus, like mutants Δ3 and Δ6, mutants Δ1 and Δ2 could generate pores, but they were unable to establish effector microinjection. The failure of these two mutants to translocate effectors may not have been due simply to low secretion levels, since we observed several LcrH mutants that exhibited comparably poor levels of YopD secretion yet still translocated effectors into infected cell monolayers with the efficiency of the wild-type strain (Edqvist and Francis, unpublished). Hence, the collective data give credence to the hypothesis that there is multistep involvement of YopD in this complex virulence strategy and that there are discrete functional domains in YopD.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of YopD synthesis and secretion from Y. pseudotuberculosis strains grown in BHI broth without Ca2+. YopD in the total fractions (mixtures of proteins in intact bacteria secreted into the culture medium) (A) and YopD in the secreted fractions (mixtures of trichloroacetic acid-precipitated proteins in cleared culture supernatants) (B) were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by immunoblot analysis by using polyclonal rabbit anti-YopD antiserum (α-YopD).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have pointed to involvement of YopD at multiple levels during type III secretion by Yersinia. Until now, it has been difficult to determine whether the collective findings are a true reflection of the role of YopD during an infection. Therefore, we performed comprehensive phenotypic mapping of sequential in-frame YopD deletion mutants of the plasmid-encoded TTSS of Y. pseudotuberculosis. Discrete functional domains were identified that were necessary to facilitate YopD secretion, LcrH chaperone binding, yop regulation, effector translocation, and pore formation (Table 3). In particular, YopD mutants that could separate pore formation in eukaryotic membranes from microinjection of antihost effectors into target host cells were isolated. Importantly, this suggested that these two events could be separated. It is noteworthy that the different functions observed for YopD encompass nearly every step of the process leading to type III-mediated translocation of Yop effectors into target cells. In view of this, it is not surprising that independent studies may result in different conclusions with respect to the function of YopD. Presumably, this would also be the case for other type III proteins from different bacterial pathogens. Despite this, our results clearly show that YopD is truly a multifunctional protein that has a mosaic of discrete domains which have individual functions.

TABLE 3.

Summary of the relevant phenotypes of each Y. pseudotuberculosis yopD allele variant

| Group | YopD variants | Phenotype

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LcrH bindinge | yop regulatory control | Secretion | Translocation | Pore formation | ||

| 1a | Wild type, Δ7, Δ8, and Δ9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2b | Δ1 and Δ2 | Yes | Yes | Yesf | No | Yes |

| 3bc | Δ3 and Δ6 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 4c | Null mutant, Δ4, Δ5, and Δ12 | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 5d | Δ10, Δ11, and Δ13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

An internal region of YopD encompassing residues 150 to 227 (Δ7 to Δ9) is dispensable for measurable YopD function.

The ability to form pores in eukaryotic membranes does not guarantee effector translocation, since translocation-defective mutants Δ1 (YopDΔ4-120), Δ2 (YopDΔ23-47), Δ3 (YopDΔ53-68), and Δ6 (YopDΔ128-149) could still form similar-size pores compared to the wild type in infected erythrocytes.

LcrH binding at positions 53 to 149 (Δ3 to Δ6) and positions 278 to 292 (Δ12) is a prerequisite for yop regulatory control.

Two domains required only for effector translocation and pore formation are located at the C terminus at positions 234 to 275 (Δ10 and Δ11) and positions 293 to 305 (Δ13).

Determined by using the yeast two-hybrid system (20).

In bacterial pathogens of animals, members of the TTSS translocon family often have multiple functions involving regulatory, structural, and effector mechanisms. This is particularly true for IpaB and IpaC of Shigella spp. (16, 43), SipB and SipC of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (16), EspB and EspD of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (16), and YopD and LcrV of Yersinia spp. (3, 13, 14; this study). This level of complexity presents obstacles to studying the individual functions of these important proteins. Therefore, the fact that we isolated three YopD mutants, Δ10 (YopDΔ234-254), Δ11 (YopDΔ256-275), and Δ13 (YopDΔ293-305),which are specifically defective in pore formation and translocation of antihost effectors into target cells but not yop regulatory control and chaperone binding, is important.

Not surprisingly, deletion of the putative coiled coil domain encompassing residues 248 to 277 (44) eliminated effector translocation. As this domain is intimately involved in protein-protein interactions (38) and is widespread in proteins of TTSSs (16, 44), this mutant phenotype supports the notion that the Yersinia translocon is a multiprotein complex that presumably includes YopD, YopB, and LcrV. However, the observed interactions of YopD with either LcrV (52) or YopB (29, 42) are not known to specifically involve the YopD coiled coil domain. Another consideration is that the coiled coil domain may initiate YopD multimerization (39, 62), which might be a requirement for biological function, as was recently proposed for PopD, a YopD homologue encoded by the TTSS of P. aeruginosa (54). To investigate the translocon complex, one approach which we have used is a comparative analysis of the functional complementation of translocon components from Y. pseudotuberculosis and P. aeruginosa (8-10). This analysis revealed that YopD and PopD, despite their similarities, were not functionally interchangeable, indicating that only interactions with native translocon members support effector translocation (8). We are currently pursuing this line of investigation with the view that the coiled coil domain may indeed confer specificity within YopD toward its binding partners. This is particularly significant since a corresponding coiled coil domain in PopD was not predicted (8).

The translocon proteins are thought to generate a pore complex in the eukaryotic membrane through which antihost effectors pass en route to the inside of infected cells (15, 36). A paradoxical finding, however, is that several of the pore components may partially localize to the target cell cytosol, resulting in an intracellular effector function (6, 16). In this regard, YopD was observed inside infected HeLa cells, but no obvious effector function was identified (22). Perhaps translocating YopD might be necessary to maintain effector molecules in a translocation-competent state during microinjection. Indeed, the fact that YopD interacts with the YopE cytotoxin in vitro (29) may well be a consequence of this putative chaperone role in vivo. In this study, we identified four YopD mutants, Δ1 (YopDΔ4-20), Δ2 (YopDΔ23-47), Δ3 (YopDΔ53-68), and Δ6 (YopDΔ128-149), that did not translocate effector proteins (YopE and ExoS), even though the pore formation in erythrocyte membranes was equivalent to that induced by mutants Δ7 (YopDΔ150-170) and Δ9 (YopDΔ207-227), which could efficiently translocate effectors. This was a surprising finding and supported the hypothesis that pore formation is not sufficient for effector microinjection. The data for these mutants indicate that there is an additional function of YopD in the translocation process that extends beyond pore formation. Interestingly, deletion of the region encompassing residues 128 to 149, which formed pores without mediating effector translocation (Δ6), corresponded to a putative hydrophobic domain (25) that is required for YopE binding (29). Taken together, these data indirectly support the hypothesis that YopD has a guidance role during translocation, and they may also have implications for the intracellular role of translocon components from other animal pathogens. In this context, the observation that mutant Δ8 (YopDΔ174-198) has an enhanced rate of ExoS translocation compared to that of wild-type Yersinia, while it exhibits an equivalent degree of lytic activity, is also very significant. Indeed, this supports our notion that pore formation in target cell plasma membranes and effector microinjection are separate events and that discrete domains of YopD are dedicated to each activity.

It is also interesting that the poorly secreting mutants Δ1 (YopDΔ4-20) and Δ2 (YopDΔ23-47) could still induce pore formation but not effector translocation. This was not due to low levels of secreted YopD, since very low levels of secreted YopD and YopB translocator proteins were all that was necessary for a subset of LcrH mutants to efficiently translocate Yop effectors (Edqvist and Francis, unpublished). Importantly, it appears that as little as the first three N-terminal amino acids are sufficient for low-level YopD secretion. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has defined the secretion domain of a translocator protein. However, a precedent for a requirement for so few N-terminal amino acids in type III-dependent protein secretion has been established. An analysis of the type III secretion signal of the S. enterica InvJ protein, which is required to control the needle length of the type III needle complex, revealed that residues 4 to 7 were predominantly required to ensure efficient secretion of InvJ (50). Whether these miniature secretion signals are universal for the type III substrates presumably secreted early during an infection, such as determinants of the outer needle and the translocators, remains a fascinating challenge for further studies.

The regulatory loops that control expression of the Yersinia plasmid-borne TTSS are innately complex (14, 58). One essential negative regulatory network was illustrated by the finding that mutants with mutations in the LcrH chaperone that are unable to bind YopD do not have yop regulatory control (21). We confirmed this observation by showing that YopD mutants that are unable to bind LcrH also are not able to control yop regulation. In this context, the finding that an LcrH-YopD complex, in association with LcrQ, is necessary for repressing translation of mRNA derived from type III genes is a key observation (2, 11). However, since LcrQ does not interact with YopD or LcrH (67), the exact mechanism of this regulatory cross talk remains unresolved.

In summary, we report the results of a thorough phenotypic analysis of in-frame sequential deletions of YopD. Our results confirmed that a YopD-LcrH interaction is necessary to maintain yop regulatory control. In addition, we established that pore formation is only one step in the process of effector translocation into target cells. Furthermore, we isolated YopD mutants that are indistinguishable from the wild type with respect to yop regulatory control but are unable to induce pores in eukaryotic membranes and to microinject antihost effectors. We concluded that YopD does function in several steps leading to efficient effector translocation by virtue of mutant phenotypes identified in (i) regulation, (ii) secretion, (iii) pore formation, and (iv) translocation. Our results should facilitate analysis of the molecular mechanisms that govern the multistep process of effector translocation by TTSSs in numerous bacterial pathogens. This may even preempt the discovery of a common antibacterial therapy targeted toward this highly refined and effective virulence strategy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (to Å.F., H.W.W., and M.S.F.), the Foundation for Medical Research at Umeå University (to M.S.F.), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (to Å.F. and H.W.W.), and the J. C. Kempes Memorial Fund (to J.O., P.J.E., and J.E.B.).

We are indebted to Maria Vedin and Stefan Lindström for skillful technical assistance, and we thank Victoria Shingler for advice concerning the chymotrypsin digestion assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aepfelbacher, M., and J. Heesemann. 2001. Modulation of Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton by Yersinia outer proteins (Yops). Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, D. M., K. S. Ramamurthi, C. Tam, and O. Schneewind. 2002. YopD and LcrH regulate expression of Yersinia enterocolitica YopQ by a posttranscriptional mechanism and bind to yopQ RNA. J. Bacteriol. 184:1287-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, D. M., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Type III machines of Gram-negative pathogens: injecting virulence factors into host cells and more. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:18-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbieri, J. T. 2000. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S, a bifunctional type-III secreted cytotoxin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergman, T., S. Håkansson, Å. Forsberg, L. Norlander, A. Macellaro, A. Bäckman, I. Bölin, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1991. Analysis of the V antigen lcrGVH-yopBD operon of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis: evidence for a regulatory role of LcrH and LcrV. J. Bacteriol. 173:1607-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blocker, A., D. Holden, and G. Cornelis. 2000. Type III secretion systems: what is the translocator and what is translocated? Cell Microbiol. 2:387-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bölin, I., and H. Wolf-Watz. 1984. Molecular cloning of the temperature-inducible outer membrane protein 1 of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 43:72-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bröms, J. E., A.-L. Forslund, Å. Forsberg, and M. S. Francis. 2003. Dissection of homologous translocon operons reveals a distinct role for YopD in type III secretion by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Microbiology 149:2615-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bröms, J. E., A.-L. Forslund, Å. Forsberg, and M. S. Francis. 2003. PcrH of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is essential for secretion and assembly of the type III translocon. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1910-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bröms, J. E., C. Sundin, M. S. Francis, and Å. Forsberg. 2003. Comparative analysis of type III effector translocation by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis expressing native LcrV or PcrV from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 188:239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cambronne, E. D., and O. Schneewind. 2002. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: yscM1 and yscM2 regulate yop gene expression by a posttranscriptional mechanism that targets the 5′ untranslated region of yop mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 184:5880-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelis, G., C. Sluiters, C. L. de Rouvroit, and T. Michiels. 1989. Homology between virF, the transcriptional activator of the Yersinia virulence regulon, and AraC, the Escherichia coli arabinose operon regulator. J. Bacteriol. 171:254-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelis, G. R. 2002. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop ′type III' weaponry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:742-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelis, G. R., A. Boland, A. P. Boyd, C. Geuijen, M. Iriarte, C. Neyt, M. P. Sory, and I. Stainier. 1998. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1315-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelis, G. R., and F. Van Gijsegem. 2000. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:735-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delahay, R. M., and G. Frankel. 2002. Coiled-coil proteins associated with type III secretion systems: a versatile domain revisited. Mol. Microbiol. 45:905-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fällman, M., F. Deleuil, and K. McGee. 2002. Resistance to phagocytosis by Yersinia. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:501-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman, M. F., S. Muller, E. Wuest, and G. R. Cornelis. 2002. SycE allows secretion of YopE-DHFR hybrids by the Yersinia enterocolitica type III Ysc system. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1183-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsberg, Å., and H. Wolf-Watz. 1990. Genetic analysis of the yopE region of Yersinia spp.: identification of a novel conserved locus, yerA, regulating yopE expression. J. Bacteriol. 172:1547-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis, M. S., M. Aili, M. L. Wiklund, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2000. A study of the YopD-LcrH interaction from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis reveals a role for hydrophobic residues within the amphipathic domain of YopD. Mol. Microbiol. 38:85-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis, M. S., S. A. Lloyd, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2001. The type III secretion chaperone LcrH co-operates with YopD to establish a negative, regulatory loop for control of Yop synthesis in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1075-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis, M. S., and H. Wolf-Watz. 1998. YopD of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is translocated into the cytosol of HeLa epithelial cells: evidence of a structural domain necessary for translocation. Mol. Microbiol. 29:799-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gemski, P., J. R. Lazere, and T. Casey. 1980. Plasmid associated with pathogenicity and calcium dependency of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 27:682-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Håkansson, S. 1995. YopB-mediated translocation of Yops and the YpkA Ser/Thr kinase of Yersinia. Ph.D. thesis. Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

- 25.Håkansson, S., T. Bergman, J. C. Vanooteghem, G. Cornelis, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1993. YopB and YopD constitute a novel class of Yersinia Yop proteins. Infect. Immun. 61:71-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Håkansson, S., K. Schesser, C. Persson, E. E. Galyov, R. Rosqvist, F. Homble, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. The YopB protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for the translocation of Yop effector proteins across the target cell plasma membrane and displays a contact-dependent membrane disrupting activity. EMBO J. 15:5812-5823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartland, E. L., S. P. Green, W. A. Phillips, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 1994. Essential role of YopD in inhibition of the respiratory burst of macrophages by Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 62:4445-4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartland, E. L., and R. M. Robins-Browne. 1998. In vitro association between the virulence proteins, YopD and YopE, of Yersinia enterocolitica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heesemann, J., B. Algermissen, and R. Laufs. 1984. Genetically manipulated virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 46:105-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henriksson, M. L., M. S. Francis, A. Peden, M. Aili, K. Stefansson, R. Palmer, A. Aitken, and B. Hallberg. 2002. A nonphosphorylated 14-3-3 binding motif on exoenzyme S that is functional in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4921-4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmström, A., J. Olsson, P. Cherepanov, E. Maier, R. Nordfelth, J. Pettersson, R. Benz, H. Wolf-Watz, and Å. Forsberg. 2001. LcrV is a channel size-determining component of the Yop effector translocon of Yersinia. Mol. Microbiol 39:620-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmström, A., J. Pettersson, R. Rosqvist, S. Håkansson, F. Tafazoli, M. Fällman, K. E. Magnusson, H. Wolf-Watz, and Å. Forsberg. 1997. YopK of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis controls translocation of Yop effectors across the eukaryotic cell membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 24:73-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmström, A., R. Rosqvist, H. Wolf-Watz, and Å. Forsberg. 1995. Virulence plasmid-encoded YopK is essential for Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to cause systemic infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 63:2269-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton, R. M., and L. R. Pease. 1991. Recombination and mutagenesis of DNA sequences using PCR, p. 217-247. In M. J. McPherson (ed.), Directed mutagenesis: a practical approach. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 36.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavander, M., L. Sundberg, P. J. Edqvist, S. A. Lloyd, H. Wolf-Watz, and Å. Forsberg. 2002. Proteolytic cleavage of the FlhB homologue YscU of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for bacterial survival but not for type III secretion. J. Bacteriol 184:4500-4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lupas, A. 1996. Coiled coils: new structures and new functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:375-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michiels, T., P. Wattiau, R. Brasseur, J. M. Ruysschaert, and G. Cornelis. 1990. Secretion of Yop proteins by yersiniae. Infect. Immun. 58:2840-2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milton, D. L., R. O'Toole, P. Horstedt, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 178:1310-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neyt, C., and G. R. Cornelis. 1999. Insertion of a Yop translocation pore into the macrophage plasma membrane by Yersinia enterocolitica: requirement for translocators YopB and YopD, but not LcrG. Mol. Microbiol. 33:971-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neyt, C., and G. R. Cornelis. 1999. Role of SycD, the chaperone of the Yersinia Yop translocators YopB and YopD. Mol. Microbiol. 31:143-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nhieu, G. T., and P. J. Sansonetti. 1999. Mechanism of Shigella entry into epithelial cells. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pallen, M. J., G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 1997. Coiled-coil domains in proteins secreted by type III secretion systems. Mol. Microbiol. 25:423-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettersson, J., R. Nordfelth, E. Dubinina, T. Bergman, M. Gustafsson, K. E. Magnusson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. Modulation of virulence factor expression by pathogen target cell contact. Science 273:1231-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Portnoy, D. A., H. F. Blank, D. T. Kingsbury, and S. Falkow. 1983. Genetic analysis of essential plasmid determinants of pathogenicity in Yersinia pestis. J. Infect. Dis. 148:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimpiläinen, M., Å. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1992. A novel protein, LcrQ, involved in the low-calcium response of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis shows extensive homology to YopH. J. Bacteriol. 174:3355-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosqvist, R., Å. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1991. Intracellular targeting of the Yersinia YopE cytotoxin in mammalian cells induces actin microfilament disruption. Infect. Immun. 59:4562-4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosqvist, R., K. E. Magnusson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1994. Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 13:964-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russmann, H., T. Kubori, J. Sauer, and J. E. Galán. 2002. Molecular and functional analysis of the type III secretion signal of the Salmonella enterica InvJ protein. Mol. Microbiol. 46:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 52.Sarker, M. R., C. Neyt, I. Stainier, and G. R. Cornelis. 1998. The Yersinia Yop virulon: LcrV is required for extrusion of the translocators YopB and YopD. J. Bacteriol. 180:1207-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schesser, K., M. S. Francis, Å. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2000. Type III secretion systems in animal- and plant-interacting bacteria, p. 239-263. In P. Cossart, P. Boquet, S. Normark, and R. Rappuoli (ed.), Cellular microbiology, 1st ed. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, D.C.11207580

- 54.Schoehn, G., A. M. Di Guilmi, D. Lemaire, I. Attree, W. Weissenhorn, and A. Dessen. 2003. Oligomerization of type III secretion proteins PopB and PopD precedes pore formation in Pseudomonas. EMBO J. 22:4957-4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilisation system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:787-796. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skrzypek, E., and S. C. Straley. 1995. Differential effects of deletions in lcrV on secretion of V antigen, regulation of the low-Ca2+ response, and virulence of Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2530-2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stainier, I., M. Iriarte, and G. R. Cornelis. 1997. YscM1 and YscM2, two Yersinia enterocolitica proteins causing downregulation of yop transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 26:833-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straley, S. C., G. V. Plano, E. Skrzypek, P. L. Haddix, and K. A. Fields. 1993. Regulation by Ca2+ in the Yersinia low-Ca2+ response. Mol. Microbiol. 8:1005-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sundin, C., M. L. Henriksson, B. Hallberg, Å. Forsberg, and E. Frithz-Lindsten. 2001. Exoenzyme T of Pseudomonas aeruginosa elicits cytotoxicity without interfering with Ras signal transduction. Cell Microbiol. 3:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sundin, C., M. C. Wolfgang, S. Lory, Å. Forsberg, and E. Frithz-Lindsten. 2002. Type IV pili are not specifically required for contact dependent translocation of exoenzymes by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 33:265-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tardy, F., F. Homble, C. Neyt, R. Wattiez, G. R. Cornelis, J. M. Ruysschaert, and V. Cabiaux. 1999. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion-translocation system: channel formation by secreted Yops. EMBO J. 18:6793-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tengel, T., I. Sethson, and M. S. Francis. 2002. Conformational analysis by CD and NMR spectroscopy of a peptide encompassing the amphipathic domain of YopD from Yersinia. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:3659-3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viboud, G. I., and J. B. Bliska. 2001. A bacterial type III secretion system inhibits actin polymerization to prevent pore formation in host cell membranes. EMBO J. 20:5373-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wattiau, P., B. Bernier, P. Deslee, T. Michiels, and G. R. Cornelis. 1994. Individual chaperones required for Yop secretion by Yersinia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10493-10497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams, A. W., and S. C. Straley. 1998. YopD of Yersinia pestis plays a role in negative regulation of the low-calcium response in addition to its role in translocation of Yops. J. Bacteriol. 180:350-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf-Watz, H., D. A. Portnoy, I. Bölin, and S. Falkow. 1985. Transfer of the virulence plasmid of Yersinia pestis to Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 48:241-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wulff-Strobel, C. R., A. W. Williams, and S. C. Straley. 2002. LcrQ and SycH function together at the Ysc type III secretion system in Yersinia pestis to impose a hierarchy of secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 43:411-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yother, J., T. W. Chamness, and J. D. Goguen. 1986. Temperature-controlled plasmid regulon associated with low calcium response in Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 165:443-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]