Abstract

Objective

Previous studies have shown that charges for inpatient and clinic procedures vary substantially; however, there is scant data on variation in charges for emergency department (ED) visits. Outpatient ED visits are typically billed using CPT-coded levels to standardize the intensity of services received, providing an ideal element on which to evaluate charge variation. Thus, we sought to analyze the variation in charges for each level of ED visits, and examine whether hospital and market-level factors could help predict these charges.

Methods

Using 2011 charge data provided by every non-federal California hospital to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, we analyzed the variability in charges for each level of ED visits and used linear regression to assess whether hospital and market characteristics could explain the variation in charges.

Results

Charges for each ED visit level varied widely; for example, charges for a level 4 visit ranged from $275 to $6,662. Government hospitals charged significantly less than non-profit hospitals, while hospitals that paid higher wages, served higher proportions of Medicare and Medicaid patients, and were located in areas with high costs of living charged more. Overall our models explained only 30–41% of the between-hospital variation in charges for each level of ED visits.

Conclusions

Our findings of extensive charge variation in ED visits add to the literature in demonstrating the lack of systematic charge setting in the U.S. healthcare system. These widely varying charges affect the hospital bills of millions of uninsured patients and insured patients seeking care out-of-network, and continue to play a role in many aspects of healthcare financing.

Introduction

Background & Importance

As healthcare costs continue to rise and patients are being asked to take increasing levels of responsibility for their healthcare costs, the lack of transparency in the current scheme of healthcare pricing is of increasing concern.1–3 Hospital charges specifically have come under recent scrutiny due to findings of wide variation in charges for inpatient episodes of care and outpatient procedures,4 as well as their devastating effects on the uninsured and out-of-network patients who are faced with paying them.5,6 Both the popular press7,8 and academic literature9 have explored the magnitude and variation in charges for typical procedures or inpatient services, bringing to light concerns about the source of differences in listed prices between hospitals.

The magnitude and variation in charges for emergency department (ED) visits, in particular, are concerning given the acute nature of most ED care, which limits a patient’s ability for “shop” for lower cost or in-network providers.10 Moreover, a disproportionate number of uninsured patients, who are directly billed for these charges, seek care in EDs.11 However, there is little data on charges for ED visits and even fewer studies exploring the issue. Data from one decade ago show that ED charges from 1996–2004 were rising,12 and recent studies have shown a wide variation in charges for common conditions that present to the emergency department.13 However, different patients presenting with the same conditions to the emergency department could have received different services, which might explain some of discrepancies in charges between hospitals. Therefore, in order to eliminate patient-driven differences in charges and isolate the degree of between-hospital variation, visit charges must be standardized for complexity and intensity of service use.

Goals of this investigation

The current system of billing the facility fee for emergency department visits at levels 1–5 allows for comparison of charges for outpatient ED visits with standardized service intensity across hospitals.14 Therefore, we examined the variability in charges for specific levels of ED visits between hospitals in California during 2011 as an example of the degree of between-hospital variability in charges, independent of patient characteristics. We then analyzed whether hospital or market level factors could explain the observed variability in charges for each ED visit level.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the variation in California hospital charges for level 1–5 ED visits (CPT codes 99281–99285) during 2011. Charge data for these services were obtained from the lists of charges for 25 common outpatient procedures that all non-federal California hospitals are required to report to the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).15 While the choice of which 25 procedures to report are at the discretion of each hospital, OSHPD provides a sample list of common procedures to aid in the reporting process. That suggested form includes ED visit levels 2–4 (99282–99284), and by 2007 over 85% of hospitals used this form in their reporting.16 The percentage likely increased by 2011. While for many other services OSHPD requests data on the average charge, including typically associated ancillary services, for evaluation and management CPT codes specifically (including the ED visit levels) only the single service charge is reported.16

To examine hospital and market-level characteristics that could help in predicting these hospital charges, we linked the charge data to OSHPD hospital utilization data files for 2011 using each hospital’s OSHPD ID number. We also linked the charge files to the Area Resource Files from the Health Resources and Services Administration to capture county uninsurance and poverty rates, and to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Impact Files to include the hospital’s relative cost of living (wage index) and case-mix index (calculated as the average diagnosis-related group relative weight for the hospital in question). All linkages used a unique identifier (hospital ID, county, and provider number, respectively), and had high match rate. Apart from children’s hospitals which do not have CMS information on wage and casemix index, all other non-merging hospitals are not systematically different from those that merge. Thus, we believe that the combined dataset is reliable and valid.

Sample selection

We only examined charges reported to OSHPD by general, non-federal, acute care hospitals. For each ED visit level, we could only include hospitals that reported charges for the relevant CPT code among their 25 common outpatient conditions. As a result, we could not reliably analyze variability in charges for level 1 and level 5 ED visits, as charges for these visit levels were only reported by four and six hospitals, respectively (likely due to their absence from the optional sample form provided by OSHPD).

Of the 307 hospitals with an ED reporting charges to OSHPD, only 240, 244, and 238 hospitals reported level 2, 3, and 4 ED visit charges, respectively. Non-reporting hospitals were statistically indistinguishable from our final sample of reporting hospitals in all institutional and market characteristics except for size, ownership, and rurality; as an example, a comparison of reporting vs. non-reporting hospitals for level 4 visit charges can be found in Appendix Table A1. We then excluded four hospitals for ED visit levels 2 and 3 and three hospitals for level 4 visits that did not report the 2011 financial data to OSHPD needed to calculate hospital characteristics, and 32, 33, and 33 hospitals, respectively, that did not have covariate data available through the CMS Impact Files. This resulted in our final samples of 204, 207, and 202 hospital charges for level 2, 3, and 4 visit charges, respectively.

Outcome

Currently, for billing purposes hospitals classify outpatient ED visits into five different levels of CPT codes (99281–5) as a standardized method to measure the intensity of services delivered and staff time expended during a particular visit in an effort to receive corresponding compensation in the form of a facility fee.17 Classification of an ED visit’s facility fee level is determined by the intensity of hospital services required for treatment. However, these procedures – for example, electrocardiograms, x-rays, and lab tests – are billed separately from facility fees. While each hospital independently classifies their visits’ facility fee levels, there are generally accepted guidelines such as the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) which describe how to assign visits to these varying categories.14

A level 1 visit is of the lowest acuity with minimal risk and resource use, such as a suture removal. Level 2 visits are generally low risk and involve such acute uncomplicated injuries or conditions as an ankle sprain. Exacerbations of chronic illnesses or acute illnesses with systemic symptoms would constitute the moderate-risk conditions of a level 3 or 4 visit. A level five ED visit includes high-risk problems, such as chest pain with a cardiac work-up or shortness of breath requiring evaluation for pulmonary embolism.14 We analyzed reported hospital charges for ED visit levels 2–4. Each hospital is required by California Law to maintain and report a single charge for each level of the facility fee that is billed to all patients regardless of payer,18 though eventual negotiated reimbursements vary by insurance carrier.

Covariates

We sought to analyze whether hospital and market characteristics influenced each facility’s charge for ED visit levels 2–4 in an effort to understand the high degree variability we observed in charges across hospitals. We based our inclusion of predictors on previous studies looking at the influence of hospital and market characteristics on aggregate price indices and individual procedures,9,19–21 and on a priori hypotheses as to factors potentially influential in hospital charge-setting.

To look at hospital-level influences on charges, we included variables for hospital ownership (for profit, non-profit, government), teaching status, urban or rural location, volume (number of licensed beds), patient payer mix (% Medicare, % Medicaid), case-mix severity, and the log of wages averaged over three years in our regression model. We further incorporated market-level factors including wage index (a measure of cost of living), percent uninsured in the county, percent below the poverty line in the county, as well as the system-wide Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI).

The HHI is a widely used economic measure of market concentration, defined as the sum of the squares of the market shares in the hospital market, which we define here to be a 20-mile fixed radius around each hospital.22 The fixed distance radius of 20-miles reflects the average distance travelled by patients for emergency care in 2011. HHI can range from 0 to 10,000 (using whole percentages), where a higher HHI indicates less competition. Our HHI calculation accounts for membership in a hospital system, since charges could be correlated among hospitals with the same owner.20 We calculated the HHI directly from patient visit counts in the hospital utilization data.

Statistical analysis

We first analyzed the variation in hospital charges for levels 2–4 ED visits using descriptive statistics. Specifically, we determined minima and maxima, 5th and 95th percentile charges, interquartile ranges, and coefficients of variation. The coefficient of variation is a unit-less measure calculated by dividing the standard deviation of charges by the mean charge, which allows for the comparison of variation across groups with different means.

To examine whether hospital or market-level characteristics are predictive of hospital charges, we regressed charges for each level of ED visit on the covariates described above. For each linear regression, we also determine the R2 value, which indicates how much of the variation in charges was explained by the hospital and market factors included in the model.

Results

We analyzed charges for levels 2, 3, and 4 ED visits at 204, 207, and 202 general acute care hospitals, respectively. Of the 202 hospitals reporting charges for level 4 ED visits, 72% were not-for-profit, 90% were located in urban areas, and 93% were non-teaching (Table 1). The hospitals had an average of 278 licensed beds, and served an average of 42% Medicare patients and 23% Medicaid patients. Characteristics of hospitals reporting charges for level 2 and level 3 ED visits are reported in Appendix Tables A2 and A3, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals reporting charges for level 4 ED visits as one of their 25 common outpatient services.

| HOSPITAL-LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| N | % | ||

| Ownership | |||

| Government | 25 | 12% | |

| NFP | 146 | 72% | |

| FP | 31 | 15% | |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 181 | 90% | |

| Rural | 21 | 10% | |

| Teaching Status | |||

| Yes | 14 | 7% | |

| No | 188 | 93% | |

| N | Mean | SD | |

| Casemix (severity) | |||

| Low | 68 | 1.32 | 0.13 |

| Medium | 67 | 1.57 | 0.05 |

| High | 67 | 1.80 | 0.14 |

| Capacity | |||

| Licensed Beds | 202 | 278 | 167 |

| Payer Mix | |||

| % Medicare | 202 | 42% | 12% |

| % Medicaid | 202 | 23% | 16% |

| MARKET-LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| N | Mean | SD | |

| Wage Index | |||

| Low | 70 | 1.17 | 0.03 |

| Medium | 68 | 1.23 | 0.03 |

| High | 64 | 1.50 | 0.11 |

| Herfindal-Hirschman Index | |||

| Low | 120 | 718 | 365 |

| Medium | 29 | 2016 | 285 |

| High | 53 | 6265 | 2900 |

| % Without Insurance | 202 | 19% | 4% |

| % Below Poverty Line | 202 | 13% | 4% |

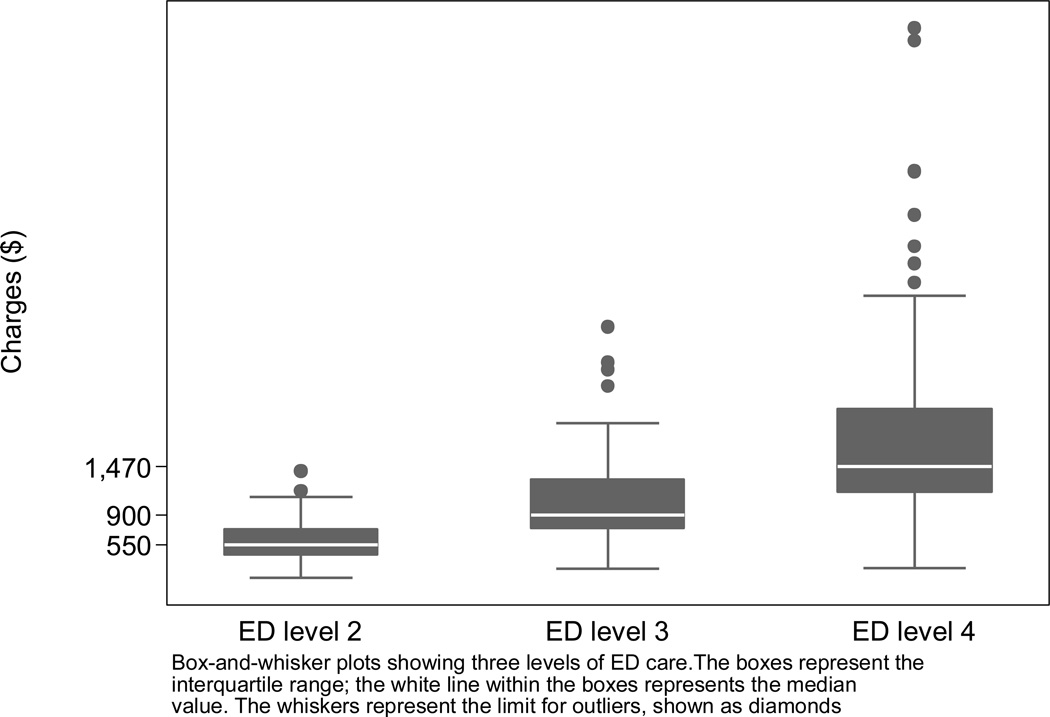

We found that charges for a level 2 ED visit ranged from $156 to $1,422; level 3, from $266 to $3,130; and level 4, from $275 to $6,662. We also further determined the range from 5th to 95th percentile of charges to exclude outliers (Figure 1; for summarized tabular form, see Appendix Table A4; for a full list of charges by hospital see Appendix Table A5). For a level 4 ED visit, for example, the hospital at the 95th percentile of the distribution charged $3,154, which is $2,745 more than the hospital at the 5th percentile, which charged $679. The interquartile range (IQR), the most conservative estimate of variation, for a level 4 ED visit was $987. We also calculated the coefficients of variation for each level of ED visit, finding that they ranged from 54% for level 4 visits to 39% for level 2 visits.

Figure 1.

Variation in hospital charges for level 2, 3, and 4 ED visits -- California, 2011.

Caption: Box-and-whisker plots showing three levels of ED care. The boxes represent the interquartile range; the white line within the boxes represents the median value. The whiskers represent the limit for outliers, shown as diamonds

In our regression analysis, for hospital-level characteristics we found that for all visit levels, government hospitals had significantly lower charges than non-profit hospitals. Non-profit and for-profit hospitals showed no significant difference (Table 2). In terms of dollars, if a non-profit charged the average of $1,720 for a level 4 ED visit, a government hospital would charge $1,118, 35% less (95% CI: −58%, −11%). In addition, all visit levels had significantly higher charges at hospitals with higher proportions of Medicaid patients; a level 4 ED visit would cost 0.55% (95% CI: 0.05%, 1.1%) more for each 1% increase in a hospital’s share of patients with Medicaid. Hospitals that paid their employees higher hourly wages also consistently charged more for all ED visit levels. For level 2 and 3 ED visits, hospitals in areas with higher costs of living, and those serving higher percentages of Medicare patients also charged more than their counterparts.

Table 2.

Linear Regression of hospital charges for each level of ED visit on hospital and market characteristics

| Percent increase in charge for each unit change in predictor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | ||||

| % rise | 95% CI | % rise | 95% CI | % rise | 95 % CI | |

| HOSPITAL-LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||||

| Ownership | ||||||

| Government | −31% | (−50, −12) | −38% | (−60, −17) | −35% | (−58, −11) |

| Non-profit | Ref | ref | ref | |||

| For-profit | −9% | (−25, 8) | −2% | (−17, 14) | 5% | (−13, 24) |

| Teaching hospital | −9% | (−31, 14) | −3% | (−31, 26) | −4% | (−39, 32) |

| Rural MSA | −4% | (−24, 15) | 12% | (−11, 35) | 15% | (−13, 42) |

| No. of licensed beds (increase per 10 beds) | 0.0% | (−0.3, 0.3) | 0.1% | (−0.2, 0.5) | 0.2% | (−0.2, 0.8) |

| Log of average wages | 79% | (39, 120) | 87% | (40, 135) | 63% | (7, 119) |

| Patient Mix | ||||||

| % Medicare | 0.81% | (0.29, 1.3) | 0.73% | (0.14, 1.3) | 0.47% | (−0.24, 1.2) |

| % Medicaid | 0.68% | (0.28, 1.1) | 0.78% | (0.34, 1.2) | 0.55% | (0.05, 1.1) |

| Casemix (severity) | ||||||

| Low | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Medium | −8% | (−20, 4) | −9% | (−23, 4) | −11% | (−27, 6) |

| High | −1% | (−15, 13) | −1% | (−16, 14) | 1% | (−16, 19) |

| MARKET-LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||||

| Wage Index | ||||||

| Low | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Medium | −18% | (−33, −3) | −22% | (−38, −5) | −10% | (−27, 8) |

| High | 27% | (8, 46) | 27% | (5, 48) | 23% | (−4, 51) |

| Herfindal-Hirschman Index | ||||||

| Low | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Medium | −5% | (−19, 9) | −2% | (−16, 12) | 3% | (−14, 20) |

| High | −4% | (−16, 9) | −2% | (−16, 12) | 6% | (−11, 23) |

| % w/o Health Ins | 1% | (−1, 4) | 1% | (−2, 4) | −2% | (−5, 2) |

| % in Poverty | 1% | (−1, 3) | 2% | (−0.3, 4) | 2% | (−0.2, 5) |

| VARIATION EXPLAINED BY THE MODEL | ||||||

| R2 | 41% | 39% | 30% | |||

Our models explained between 30% and 41% of the variation in charges for ED visits (Table 2), leaving the majority of the variation in charges unexplained. As noted above, government ownership, proportion of patients covered by Medicaid, and the log of average wages were the only factors that consistently, significantly predicted the variation in charges. Teaching affiliation, for-profit ownership, rural location, size, case-mix, proportion of poor and uninsured patients in the surrounding county, and market competition did not significantly predict the variation in charges for any level of ED visit.

Limitations

Our analysis is limited to California, which, while a large and diverse state, does not represent the entire nation. However, California can serve as a useful example of variation in charges for ED care. In addition, we use self-reported data from hospitals, which could be subject to bias and error. However, we expect that any discrepancies are limited, as OSHPD performs periodic financial audits of the data. Further, it is possible that if we had included the hospitals that did not report charges to OSHPD, our estimates of the influence of hospital characteristics on charges may have shifted. However, given that the non-reporting hospitals are generally very similar to our final regression sample, we doubt the bias is very significant. It is also worth noting that the case-mix index used in this analysis is calculated by CMS using inpatient DRG severity, which may not perfectly transfer to the severity of patients seen in the ED.

In addition, though our model attempted to capture all potentially relevant hospital and market level factors affecting charges as determined a priori, there are certainly other less easily measured characteristics of each hospital (e.g. facility features, throughput efficiency, staffing level) that contribute to fixed costs and could differentially affect charges even for theoretically uniform units like ED visit levels. Further, market and patient population characteristics such as racial and ethnic composition, housing prices, and age dispersion, which we chose not to include in our model due to their absence from previous literature on hospital-level charges20,21 and overlap with existing variables in our analysis, could influence the variability we observe. Thus, it is possible that some proportion of the variation that remains unexplained could be explained by additional characteristics of the hospital or market not included in our model.

Finally, given that there are not strict definitions for what constitutes each fee level, it is possible that a hospital systematically groups slightly less severe patients into higher levels, depressing the charges set by that hospital compared to others, or vice versa, which could explain some between-hospital variation in charges. While we understand we cannot completely account for this differential coding, we attempted to control for overall differences in severity that may shift all charges by including each hospital’s case-mix as a covariate in our models. In addition, given the widespread use of HCPCS standards, along with periodic auditing for violations of the CMS guideline prohibiting upcoding, we doubt these differences are significant enough to explain the entire wide degree of variation in charges.

Discussion

We found a wide range in charges for the same ED visit level across California hospitals in 2011. Charges for a level 4 visit, for example, ranged from $275 to $6,662, with a coefficient of variation of 54%. For comparison, a previous study measured the average coefficient of variation for consumer electronic goods sold online at 12.5%.23 Differential patient presentation and service intensity between hospitals is unlikely to account for this wide variation in charges, as facility fee levels for ED visits attempt to standardize the degree of resource use and medical complexity among groups of patients for uniform prospective reimbursement within levels.14

Some hospital and market characteristics did help predict the hospital’s charge for a specific level of ED visit. For level 2, 3, and 4 visits, we found that government hospitals charged significantly less than non-profit hospitals, while hospitals with higher proportions of Medicaid patients and hospitals in areas with the highest costs of living charged significantly more than their counterparts. These findings are generally aligned with previous literature examining the predictors of broad inpatient price indexes.20,24 Further, the positive correlation between charges and the proportion of patients covered by Medicaid, which has relatively low reimbursement rates, might be interpreted by some to be cost-shifting to the more generously reimbursing privately insured patients in an effort to maintain overall hospital solvency.25 However, there is a strong economic argument that wider price discrimination between insurers, as perhaps implied by higher charges, does not necessarily imply cost-shifting and instead is intended by physicians and hospitals for profit maximization.26

Of perhaps greater note, however, is that our models only explained 30–41% of the variation in charges for each level of ED visit. This left the majority of the wide variation in charges unexplained by our observable hospital and market-level factors. This could be due to either our inability to capture all relevant predictive hospital or market factors, or to purely random variation between hospitals.

Past research on the chargemaster system suggests that much of the variation we observe may in fact be entirely random. Charges are often set using historical prices determined before the costs of the services involved could be accurately measured, making the baseline values largely arbitrary.27 Even today, third party prospective payments are often also set without regards to explicit costs, eliminating incentives for hospitals to consider costs when setting charges.28,29 Perhaps as a result, charges are often updated uniformly and without regard to the real changes in costs of each service.27 This distorts the value of services and makes services for which productivity has increased over time the most profitable, often subsidizing others.29 These system-wide practices preclude a relationship between charges and cost, which in most other industries provides an anchor for prices. Therefore, the high degree of variability in charges for ED care observed in this unregulated system is almost – unfortunately - to be expected.

Though often regarded as irrelevant, this largely arbitrary chargemaster system in fact has major bearing on the cost of medical care. Uninsured and insured patients seeking care out-of-network are still billed these full charges for their emergency department care. An uninsured patient visiting the ED for an ear infection requiring antibiotics, a level 3 visit, could face between $266 and $3,130 for his care, depending solely on the hospital he visited. When facing a medical emergency, few patients have the ability to shop around for the cheapest care, making variation in ED charges especially concerning for these patients. In fact, even if a patient took the time to shop around for care, lack of transparency in charges and prices would make comparison difficult,3 and questioning the provider at the time of service would likely be unfruitful, given that physicians have difficulty estimating the cost of the care they provide.30 The magnitude of the total charges faced by patients for ED care can be so extreme that, barring charity care or sliding scale income level adjustments, they can result in bad debt for patients, and even bankruptcy.6,31,32 For insured patients seeking care out-of-network, hospitals will seek reimbursement from patients and their health plans based on full charges – in fact, this is a highly contentious point that has been under litigation.33 Second, charges have trickle-down effects on privately insured patients, even if they are in network. For instance, negotiations of fee-for-service reimbursements with many third-party payers are based on charges, and some payers even benchmark their prospective payment systems on charges.29,32 Through these negotiations, charges affect insured patients’ out of pocket costs. Finally, most hospitals use charges to calculate their uncompensated care costs,34 and inflated charges therefore benefit the hospital’s ability to qualify as tax-exempt. As a result, they may avoid tax obligations that could provide critical revenue to local, state, and federal governments.35

California has attempted to limit these effects by implementing the Fair Pricing Act of 2006, which requires hospitals to offer income-based adjustments and charity care to patients with an income <350% of the Federal Poverty Line or with out-of-pocket medical expenses >10% of their annual income. However, even existing state legislation regarding hospital billing is vague and often unenforced.36 Reduced bills can still be based on charges, and thus continue to vary dramatically between hospitals. Other states have tried different strategies to ease the financial burden of charges on the uninsured. For instance, Maryland sets facility fees that are the same regardless of the insurance status of the patient,37 and New Jersey has written into law that uninsured patients are only responsible for no more than 15% greater than the Medicare reimbursement for the same service.38 Nevertheless, these states remain in the minority, and in most states the uninsured still pay at least a reduced fee based on charges. Further, implementation of the Affordable Care Act is expected to newly insure between 25 and 26 million people, reducing the prevalence of the financial impact of charges.39 In spite of this, it is estimated that between 30 and 31 million Americans will remain uninsured in 2016, and will still feel the impact of charges.39

In conclusion, we find that significant variation in charges exists between hospitals for level 2–4 ED visits. While some hospital and market characteristics can predict charges, a significant amount of variation remains unexplained by our model. Our findings add to previous literature in demonstrating the lack of systematic charge setting, which especially in medical emergencies can have devastating effects on patients facing the full bill for their care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We especially thank Julia Brownell, BA, for her editorial assistance.

Financial Support: This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 TR000143 (RYH), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars (RYH), and a UCSF Center for Healthcare Value grant. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies. The funding sponsors played no part in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Meetings: Scientific Assembly, American College of Emergency Physicians, Seattle, WA October 14–17, 2013

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: RYH and YAA both conceived of and designed the study. YAA conducted the data analysis, RYH and YAA critically interpreted and revised the analysis, and RYH drafted the manuscript and provided funding. RYH and YAA both revised the manuscript for intellectually important content.

References

- 1.The Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Research & Educational Trust. Employer Health Benefits 2012 Annual Survey. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Actuary. National Health Expenditure Projections 2011–2021. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government Accountability Office (GAO) Meaningful Price Information Is Difficult for Consumers to Obtain Prior to Receiving Care. GAO-11-791; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Provider Charge Data. [Accessed May 28, 2013];2013 < http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/index.html>.

- 5.Brill S. Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills Are Killing Us. TIME Magazine. 2013 Feb 20; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier B, McGinty JC, Creswell J. Hospital Billing Varies Wildly, Government Data Shows. The New York Times. 2013 May 8; A1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kliff S, Keating D. One hospital charges $8,000 — another, $38,000. [Accessed February 11, 2014];The Washington Post. 2013 May 8; Wonkblog [internet] < http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/05/08/one-hospital-charges-8000-another-38000/>. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsia RY, Kothari AH, Srebotnjak T, Maselli J. Health care as a "market good"? Appendicitis as a case study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(10):818–819. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginsburg PB. Shopping for price in medical care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):w208–w216. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham P, May J. Insured Americans Drive Surge in Emergency Department Visits. Washington DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsia RY, MacIsaac D, Baker L. Decreasing Reimbursements for Outpatient Emergency Department Visits Across Payer Groups From 1996 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(3):265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. "How Much Will I Get Charged for This?" Patient Charges for Top Ten Diagnoses in the Emergency Department. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e55491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Emergency Physicians. ED Facility Level Coding Guidelines. [Accessed December 5, 2013];2011 < http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=30428>. [Google Scholar]

- 15.California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Annual Financial Data: General Information About the Hospital Chargemaster Program. [Accessed April 3, 2013];2012 < http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Products/Hospitals/Chrgmstr/index.html>.

- 16.Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Instructions for Completing and Submitting Average Charge for 25 Common Outpatient Procedures Required by Payers’ Bill of Rights. [Accessed December 9, 2013];2008 < http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Products/Hospitals/Chrgmstr/AB1045InstructionsCommonOPProcedures.pdf>.

- 17.Kaskie B, Obrizan M, Cook EA, et al. Defining emergency department episodes by severity and intensity: A 15-year study of Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:173. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payers’ Bill of Rights. California Health and Safety Code Section 1339.50 – 1339.59. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaynor M, Vogt WB. Competition among hospitals. RAND J Econ. 2003;34(4):764–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnick G, Keeler E. The effects of multi-hospital systems on hospital prices. J Health Econ. 2007;26(2):400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melnick GA, Zwanziger J, Bamezai A, Pattison R. The effects of market structure and bargaining position on hospital prices. J Health Econ. 1992;11(3):217–233. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(92)90001-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Horizontal Merger Guidelines. [Accessed April 1, 2013];2010 < http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/guidelines/hmg-2010.html>.

- 23.Baye MR, Morgan J, Scholten P. Temporal price dispersion: Evidence from an online consumer electronics market. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 2004;18(4):101–115. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeler E, Melnick G, Zwanziger J. The changing effects of competition on non-profit and for-profit hospital pricing behavior. J Health Econ. 1999;18(1):69–86. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwanziger J, Bamezai A. Evidence Of Cost Shifting In California Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(1):197–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinhardt UE. The many different prices paid to providers and the flawed theory of cost shifting: is it time for a more rational all-payer system? Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2125–2133. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobson AJ, DaVanzo J, Doherty J, Tanamor M. A Study of Hospital Charge Setting Practices. Lewin Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginsburg PB. Wide variation in hospital and physician payment rates evidence of provider market power. Center for Studying Health System Change; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsburg PB, Grossman JM. When the price isn't right: how inadvertent payment incentives drive medical care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005:W5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Innes G, Grafstein E, McGrogan J. Do Emergency Physicians Know the Costs of Medical Care? CJEM. 2000;2(2):95–102. doi: 10.1017/s148180350000467x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinhardt U. What Hospitals Charge the Uninsured. [Accessed February 11, 2014];The New York Times. 2013 Mar 15; Economix Blog [internet]. < http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/15/what-hospitals-charge-the-uninsured/>. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinhardt UE. The Pricing Of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos Behind A Veil Of Secrecy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(1):57–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prime Healthcare Services Inc. v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan: Cross-complaint by Kaiser Defendants. Superior Court of the State of California for the County of Los Angeles; 2010. Jun 17, pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Internal Revenue Service. IRS Exempt Organizations (TE/GE) Hospital Compliance Project Final Report. 2006:98. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattera P. Uncharitable Charities: Non-profit hospitals are under fire for mistreating the uninsured. [Accessed January 8, 2014];2006 http://www.corp-research.org/e-letter/uncharitable-charities. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockwell Farrell K, Finnocchio L, Trivedi A, Mehrotra A. Does Price Transparency Legislation Allow the Uninsured to Shop for Care? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):110–114. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray R. Setting Hospital Rates To Control Costs And Boost Quality: The Maryland Experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(5):1395–1405. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conaway HJ, Moriarty PD. Assembly No. 2609. The State of New Jersey; 2008. [Accessed February 11, 2014]. < http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2008/Bills/A3000/2609_I1.PDF>. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nardin R, Zallman L, McCormick D, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein D. Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD: 2013. [Accessed February 11, 2014]. The Uninsured After Implementation Of The Affordable Care Act: A Demographic And Geographic Analysis. < http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/06/06/the-uninsured-after-implementation-of-the-affordable-care-act-a-demographic-and-geographic-analysis/>. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.