Abstract

A ‘companion diagnostic’ is a test for a predictive biomarker, that classifies patients (tumors) into responders and non-responders, for a specified therapeutic agent. Companion diagnostics are designated as Class III medical devices by the FDA, because the test result equates directly to administration of a drug.

Testing for HER2 expression was approved by the FDA in 1998, and served as the prototype for using immunohistochemistry (IHC) as the basis for a companion diagnostic. However, over four decades IHC has primarily been employed in a broad range of ‘special stains’, for identification and classification cells and tumors in FFPE (formalin fixed paraffin embedded) tissues. During the long use of IHC as a ‘special stain’ we have acquired some very bad habits, changing protocols, concentrations, incubation times, retrieval methods, or reagents, to achieve the perception of a ‘good’ stain, that ‘pleases the eye’ of the user pathologist. While this approach may be acceptable for IHC stains, it is a recipe for disaster when transferred to companion diagnostics, where quantification and absolute reproducibility are required. In the context of companion diagnostics the IHC method should be regarded as an assay, not simply a stain. Elevating IHC to a true immunoassay will necessitate a much more rigorous approach to performance, reproducibility and control. The ultimate goal is to supplement morphologic judgment with precise measurement of proteins in tissues and in individual cells, ‘in situ proteomics’ as it were.

Introduction: Definitions

Predictive biomarkers are so named because the level of expression in a tumor may be of value in predicting the effectiveness of a particular ‘targeted’ therapy for that specified tumor.

A ‘companion diagnostic’ is a test or assay that detects a predictive biomarker, thereby allowing classification of patients (tumors) into responders and non-responders, for the corresponding therapeutic agent.

The terms ‘companion diagnostic’, ‘predictive diagnostic’, ‘precision diagnostic’, ‘theranostic’, and ‘advanced personalized diagnostic’ are to a degree used synonymously, such that the context of use is important1,2. A companion diagnostic is defined in relation to a specified therapeutic agent, and is approved by clinical trials that establish utility for classifying patients into responders and non-responders for the drug in question. Companion diagnostics are classified as Class III medical devices (IVD – in vitro diagnostic) by the FDA, because the risk of the companion diagnostic equates to the risk of the drug that may be administered (solely) on the basis of a positive test.3–6

The technical basis of a companion diagnostic test relates to the predictive biomarker that it purports to detect, as summarized in pending regulatory review within the US:- ‘Advanced Personalized Diagnostics – An analysis of DNA, RNA, chromosome, protein or metabolite –for purpose of diagnosis, prevention, cure, mitigation or treatment—excluding ‘routine methods’.3 Technical methods may thus encompass PCR, RT-PCR, expression arrays, Next Generation Sequencing, FISH, Mass Spectroscopy, Immunohistochemistry and others.

This article concerns itself with the challenges and opportunities that the rapid growth in demand for companion diagnostics presents for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Immunohistochemistry: in the beginning

Over the past four decades IHC has primarily been employed to provide a broad range of ‘special stains’, that mostly are used for identification and classification cells and tumors in FFPE (formalin fixed paraffin embedded) tissues. If success is to be measured in terms of the number of different ‘IHC stains’ that are in daily use, or have been reported, then the IHC method must be judged a resounding success, for the number runs into the thousands, including published IHC ‘stains’, and listings in vendor catalogs of primary antibodies suited to IHC on FFPE tissues. However, the sheer scale of use, the success of the method, conceals major deficiencies of practice.

Immunohistochemistry: – a ‘stain’, or an ‘in situ’ tissue based immunoassay?

In its traditional use as a ‘stain’ the IHC result is judged by a tinctorial reaction, the generation of color, positive or negative for the cell or tissue of interest. This judgment is purely qualitative and it is subjective, depending upon the eye and experience of the pathologist, albeit with reference to control tissues, the assessment of which also is subjective.

In the long use of IHC as a ‘special stain’ we have acquired some very bad habits. Laboratory technicians and pathologists are accustomed to adjusting the IHC protocol, changing concentrations or incubation times, or retrieval methods, or reagents, to achieve ‘good’ stains on tissues prepared at a particular institution, where ‘good’ is defined as a result that ‘pleases the eye’ of the user pathologist. While this approach may be acceptable for IHC stains, when interpreted in the presence of experience and proper controls, it is a recipe for disaster when transferred to companion diagnostics, where absolute reproducibility and some form of quantification are required.

Companion diagnostics should be regarded as assays, not as stains7

When IHC is used as the basis for a companion diagnostic there is an implied transition from a stain to an assay, with elements of quantification. The question is no longer one of whether the target protein is present (a positive ‘stain’), but rather it is a question of how much of the target protein (or analyte) is present, requiring quantitative assessment (How much per cell? What percentage of cells?)7,8.

The ELISA assay (enzyme linked sorbent assay) is a ‘gold standard’ method for measurement of the amount of an analyte (e.g. protein) in blood and other biological fluids. Measurements by ELISA are both accurate and reproducible, based upon ‘color generated’ under strictly controlled conditions and measured against a calibration or reference standard. ELISA employs specific antibody and a chromogenic detection system analogous in principle to IHC7, but whereas ELISA gives results that are widely accepted to be both quantifiable and reproducible, IHC does not. The reasons are related to differences in practical performance, and are potentially open to improvement for IHC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Enzyme Linked Immunoassay (ELISA) as compared to Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

| ELISA | IHC | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample preparation | Defined and standardized: specimen rejected if not compliant | Absence of agreed standards Absence of monitoring for compliance |

| Protocol - Defined, validated reagents - steps in protocol - automated |

Specified for assay Closed Yes; with fixed protocol for the instrument |

Wide choice, validation varies Open and frequently ‘tweaked’ Partial; reagents and protocols can vary |

| Reference standard | Available, for control and for calibration | Not available 1; controls vary from lab to lab. |

| Interpretation | Computer based readout with reference to calibration standard | Mostly manual and subjective |

Fixed cell line sections included in approved diagnostics kits are prepared so as to give consistent protein expression, but cannot be used to calibrate (measure) results in FFPE tissues as preparation and fixation differ.

Companion Diagnostics: in the beginning

Approved by the FDA in 1998, the ‘Her2 test’ (HercepTest -Agilent-Dako; Carpinteria, CA, USA) served as the prototypic companion diagnostic for IHC. A positive result classifies a patient as a ‘responder’ to targeted therapy with Trastuzumab (Herceptin – Genentech, CA) directed against ERBB2 (HER2) ‘over’ expressed on the cancer cell membrane. Approval of the test by the FDA was (and is) specific for all aspects of the test, including reagents, cell line controls, protocol and scoring parameters, as defined in the approved package insert9. The original approved scoring method was ‘semi-quantitative’, by a pathologist with a microscope; 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+, based upon intensity of membrane staining, percentage of stained cells and pattern of staining (partial or complete). Scores of 0 and 1+ were deemed negative (non-responders) and 2+ and 3+ were classed as positive (responders). Other vendors have developed approved HER2 tests that are similar, but not identical. More recently, computer driven algorithms performed on digital Whole Slide Images (WSIs) have been approved by the FDA as providing interpretation of HER2 results that in clinical trials is equivalent to that obtained by experienced pathologists with the manual method.

In addition, FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) testing for HER2 gene amplification has emerged as a second ‘approved’ test, and often is used as a supplementary method in those cases where IHC HER2 testing gives results that are ‘equivocal’. In practice these often are cases where the IHC results are close to the scoring threshold for positive versus negative. This ability to reflex ‘equivocal’ cases to a second independent method will not be available for many upcoming companion diagnostics, placing much greater reliance upon a scoring method that is easily taught and easily learned, and is effective and reproducible, especially at the threshold.

Growing demands for Companion Diagnostics and IHC

Over the past decade the number of potential targeted therapies has grown exponentially10–14, and with it the need for companion diagnostics. Approval of a ‘companion diagnostic’ depends upon clinical demonstration of effectiveness of the test in classifying responders versus non-responders, necessitating close collaboration between the manufacturers of the drug and the test. Any change in parameters of the approved test (reagents, protocol, scoring) requires re-validation, and a new approval process. Indeed, within months of approval of the original HercepTest in 1998, publications showed that changing the test conditions changed the test results, affecting clinical sensitivity with respect to responders and non-responders. The issue of reproducibility of IHC testing for Her2 remains a concern to the present day and scoring guidelines have changed more than once15–18.

Many targeted therapies have as their targets, proteins. Immunohistochemistry, demonstrating both the protein and its cellular localization is, therefore, in theory, the ideal method upon which to base a companion diagnostic. Here there are lessons to be learned from more than a decade of IHC testing for Her2 (18). Under ideal circumstances differences in levels of Her2 expression as detected by the test (0, 1+, 2+, 3+) are directly reflective of the biology of the tumor (1. In Table 2), but experience has shown that many other factors influence the reported result, affecting reproducibility of test results and their interpretation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors affecting the results of IHC staining of tissues.

| Major factors affecting the reported results of IHC staining. |

|---|

| 1. THE BIOLOGY OF THE TUMOR |

| 2. Variations in sample acquisition, transport, preparation and fixation. |

3. Multiplicity of reagents and methods.

|

| 4. Variable choice of control cells or tissues, and lack of uniform reference standard(s). |

| 5. Inconsistencies in scoring of the result (intensity versus percentage of positive cells). |

Variations in sample acquisition, preparation and fixation

The issue of inconsistent sample preparation has emerged as a key factor affecting the reproducibility of an IHC test, extending from ‘warm ischemia’, through ‘cold ischemia’ (specimen transport), to fixation and processing of formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue, which is generally the material available for testing in the clinical arena. The adverse impacts of cold ischemia and fixation time vary independently of one another, and are different for different antigen/antibody pairings, ranging from minimal for some, to catastrophic for others. In addition, there is an almost complete lack of hard data describing the behavior of specified proteins or analytes under these different conditions.

One approach to inconsistent sample preparation has been to develop guidelines, including minimizing ischemia time, and defining (and documenting) fixation time17–20. There is an expectation that outcomes will be improved by this approach, but logistical and cost issues are formidable, and there is presently no reliable method of monitoring compliance with guidelines for any particular tissue specimen, either within an institution or across institutions.

Another approach has been to develop ‘molecular friendly fixatives’, purported to have fewer adverse effects on the ‘antigenicity’ of proteins than experienced with FFPE tissues. Again the challenges of orchestrating change by multiple laboratories to an improved fixative, even if all could agree upon what that fixative might be, have to date proved insurmountable. The problem is compounded by the inevitable outcome of gradually accumulating ‘newfixed’ tissues that are not comparable to archival FFPE tissues for IHC (or molecular analysis), and by attendant differences in basic morphology, whether real or perceived.

A third approach is based upon ‘qualifying’ an FFPE tissue section as suitable for performance of a particular IHC test (assay) by use of internal control proteins. This proposal parallels ‘routine practice’ in molecular testing, whereby measurement of a ‘housekeeping gene’ or product (e.g. actin) serves as a quality control21,22 and under specified conditions may serve as a calibration or reference standard7,8.

Multiplicity of reagents and methods

Studies by external QC organizations, such as NordiQC23 and UKNEQAS24, have shown an astonishing range of variation among different laboratories with respect to choice of reagents, retrieval methods and staining protocols (automated or manual). For example, in one UKNEQAS survey encompassing 365 laboratories performing an ‘IHC stain’ for keratin, twenty six different primary antibodies were employed, with more than 20 different detection systems from 13 vendors, using 17 different auto-stainers or manual methods. This enormous diversity represents a great problem for the reproducibility of IHC in general, and becomes a critical issue for ‘companion diagnostics’, where the question asked of the test is much more rigorous; not just is the protein present (a positive stain), but how much protein is present on a comparative basis from case to case? Just as the question is more rigorous so the demands of test performance are much more rigorous.

Some of these problems stemming from diversity of reagents and protocols are addressed by use of ‘kits’ (IVDs) approved by the FDA or by comparable agencies in other countries, and by automation, which has the side benefit of ‘forcing’ some standardization by restriction in practical choice of reagents and protocol.

The use of an FDA approved test (Class III, IVD) restricts the performing laboratory to a specified reagent set and a closed protocol, and to an internal validation process that provides some assurance of run to run stability. It must be remembered that any deviation from reagents or protocol negates validation. Such deviations include differences in antigen (or epitope) retrieval protocols (solutions and heating methods), which have been shown to have profound effects upon the ability to demonstrate proteins by otherwise standard protocols (in the UKNQAS survey cited above 17 different retrieval solutions were employed)24.

Choice of control cells or tissues, and lack of uniform reference standard(s)

Recent reviews in AIMM25–27 reflect increased focus on the critical importance of using proper controls in order to achieve high quality consistent IHC results. To a large extent this focus on improved controls has been driven by the desire to use IHC for companion diagnostics.

The basic controls used in IHC ‘staining’ are listed in Table 3. Other controls exist and more extensive treatment of the topic of controls for IHC may be found in specialized texts and manuals20, 26,–29. The following brief discussion emphasizes the need for higher order controls if IHC is to be used successfully in companion diagnostics.

Table 3.

Basic Controls in Immunohistochemistry.

| Control | Preparation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Negative reagent control (NRC) | Specific reagent (usually primary Ab) is replaced with non-reacting reagent on parallel FFPE section. | Detect false positive staining due to labeling system or other protocol steps. |

|

| ||

| Negative tissue control | ||

| a. external1 | Tissue section other than patient test tissue Identical protocol, FFPE similar but not identical to test section. |

Identification of ‘false positive’ staining of structures known not to express the target antigen. |

| b. internal – using tissue/cell elements in test section | ‘Negative’ cell elements in patient test slide FFPE and protocol identical – as intrinsic part of test section. |

|

|

| ||

| Positive tissue control | ||

| a. external 1. | Tissue section 2. other than patient test tissue. Identical protocol, FFPE similar but not identical to test section. |

Identification of false negative results; failure to stain structures known to express the target antigen. |

| b. internal – using tissue/cell elements in test section | Cell elements in patient test slide FFPE and protocol identical – as intrinsic part of test section. |

|

|

| ||

| External Quality Control Systems | External slides provided by UKNEQAS, NordiQC, CAP3, CIQC3 | Provides assessment of validity of staining (and interpretation). |

External because the tissue is ‘external’ to the patient test section, as opposed to ‘b. internal’. Such tissue is usually obtained ‘in house’, which means that sample preparation and fixation may be similar to the test tissue but is not identical. Tissues obtained from sources outside of the lab are external in another sense, and may have undergone even more diverse preparation; purchased multi-tissue arrays and cell line pellets are in this category.

It is not possible today to provide identical FFPE tissues as part of approved IVD companion diagnostic kits; FFPE cell line pellets are often used instead (see Table 1). These cell line pellets do not control for sample preparation and FFPE.

CAP, College of American Pathologists; CIQC, Canadian Immunohistochemistry Quality Control.

Most approved IVD companion diagnostics require performance of NRCs (negative reagent controls) as part of the approved protocol. This mandate reflects concern that a false positive result would result in inappropriate administration of the ‘companion’ drug to a patient who would be unlikely to benefit, with associated possible side effects, not to mention high economic cost. In view of the recent relaxation of CAP recommendations, allowing performance of NRC ’at the discretion of the laboratory director’ when using polymer based detection methods25,26, it is possible that this requirement might at some point be relaxed; however, at present, if required by the approved protocol NRCs should be performed.

External positive controls are important to demonstrate that the companion diagnostic IHC assay produces the expected signal in tissue (or cells) known to contain the target analyte. FDA approved ‘kits’ such as the HercepTest include sections of FFPE cell line pellets (negative, low and high positive) for this purpose, meeting general recognition that a positive control should be of a relatively low signal intensity, so as to detect decreased assay performance27. Note that sections of known positive cases, even when obtained in house from other patients, give only general information as to the suitability of sample preparation, including FFPE fixation26–29.

Only true tissue internal controls meet the requirements of having undergone all stages of sample preparation and IHC protocol in a manner identical to the test analyte, because, by definition, the internal control protein is located in the same tissue section alongside the test protein.

Inconsistencies in scoring of result (intensity versus percentage of positive cells)

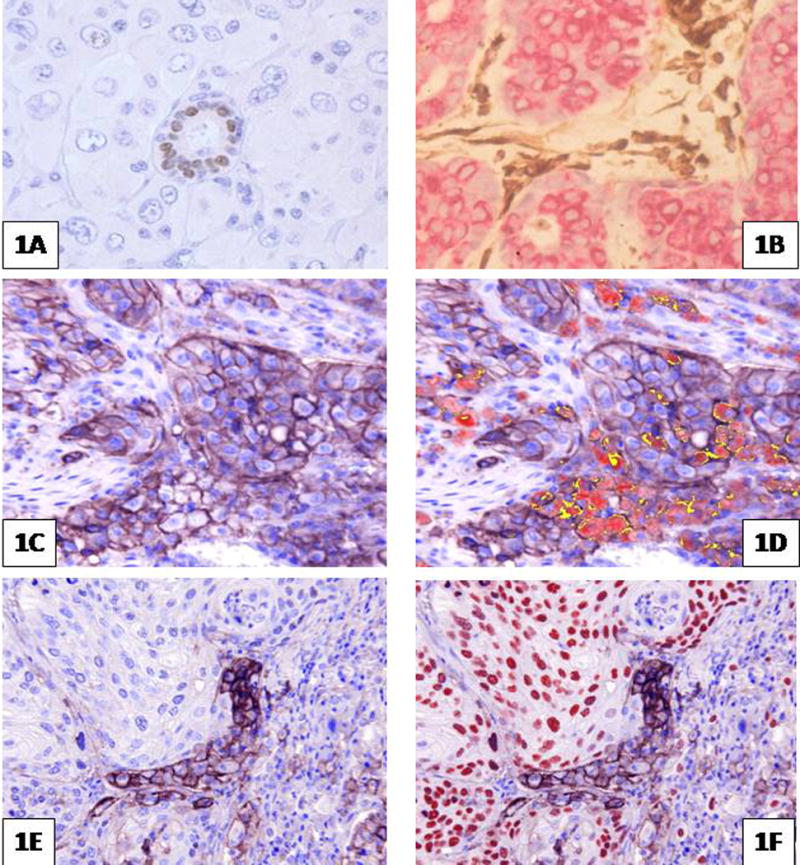

Internal tissue controls are employed by pathologists, almost unthinking, in almost every case, exemplified by evaluating plasma cells when staining for kappa or lambda light chain, or residual normal breast ducts in a case of breast cancer that is otherwise non-reactive for ER (Figure 1A). Indeed in the 1980s Hector Battifora and others adopted the notion of employing observed positive staining for vimentin (Figure 1B) as a kind of surrogate marker that fixation had left at least one protein sufficiently intact for successful IHC staining. Assessment was purely qualitative.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical ‘stains’. 1 A and B. Examples of internal positive controls: 1A. ER (estrogen receptor) positive residual duct in a case of ER negative breast cancer. 1 B. staining for vimentin (brown) (keratin is stained red). 1 C. through F shows an antibody to PD-L1 giving variable (brown) membrane staining of cancer cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. 1 C and D show adenocarcinoma of lung; in 1D recognition of macrophages is aided by multiplex red stain for CD68 (co-localization of PD-L1 and CD68 on macrophages shows yellow). 1 E and F show squamous carcinoma of lung; in 1F distinction of cancer cells from PD-L1 positive macrophages is aided by nuclear staining of cancer cell nuclei (red) with antibody to p63. Images using Nuance Spectral separation software.

The use of internal or intrinsic proteins has been proposed as a method for qualifying a specimen as suitable for IHC staining7,8,22. This approach also may be extended to form a more extensive system of ‘quantifiable internal reference standards’ (QIRS), as a means of rendering a quantitative measurement by IHC7,8. The method would require the minimum of a ‘double IHC stain’, demonstrating both the internal reference standard (protein) as well as the test analyte (protein) in the same tissue section, followed by image analysis for comparative measurement and quantification. Digital image analysis is necessary, because the subtle changes in intensity and distribution for precise measurement cannot be assessed by the human eye.

Digital image analysis also will be essential when ‘multiplex’ IHC protocols are employed for improved discrimination among cells types, as when attempting to score localization of a biomarker on tumor cells versus other cell types (e.g. Carcinoma cells versus macrophages for PD-L1)(Figure 1 C–F). Such approaches already have been employed in fluorescence based systems for improved quantification and for cell recognition30,31, and equally are applicable to high order multiplex staining of bright field images that are obtained by repeated sequential staining of biomarkers on the same tissue section32,33.

In situ proteomics

Today, classification of cancers (patients) into responders and non-responders for a plethora of targeted therapies cannot be achieved by pathologist and microscope alone10. Neither is the answer entirely to be found in newer molecular methods, when practiced upon extracts of ‘biopsy tissues’, in which the proportion, or even the presence, of cancer cells is unknown, and all aspects of heterogeneity of expression by tumor and stromal elements are lost.

The prototypic companion diagnostic for HER2 has survived to this day, in spite of ongoing concerns with regard to accuracy and reproducibility. As discussed, some of these concerns were attributable poor sample preparation or variations in protocol, but others related to lack of reproducibility of scoring by pathologists, relating to both intra-observer and inter-observer consistency. The introduction and approval of digital algorithms applied to WSIs was a response to this last problem, with improvement in consistency18, even though the potential capability of the image analysis method was restricted by an approval process that sought only to replicate the semi-quantitative scoring achieved by pathologists with a microscope. In this respect the full potential of computer assisted image analysis for quantification and measurement in the context of a morphologic environment has yet to be exploited.

The demand for precision, objectivity and reproducible measurement does not necessarily represent the end of the microscope or of ‘Surgical Pathology’, but it does represent the end of a long beginning, how for a century and a half the histolopathologic classification of a tumor has been a primary factor in selection of therapy30. Optimistically these new demands may represent the beginning of a new era, supplementing morphologic judgment with precise measurement of proteins in tissue and individual cells, tissue based immunoassays, ‘in situ proteomics’ as it were.

Summary

With the pending flood of new companion diagnostics, some of which are IHC based, the problems encountered with the HER2 test will be revisited, time and time again. The outcome is not difficult to predict by reference to the history of the introduction of ELISA into the clinical laboratory (Table 1). Already much greater attention is being given to all aspects of tissue sample preparation for IHC, with attempts to document and standardize across institutions. However, the logistical and cost issues are formidable and is not likely that the level of standardization achieved on blood or fluid samples for ELISA can ever be achieved for tissues and IHC. It appears probable, therefore, that some method of ‘qualifying’ a tissue sample as suitable for performance of a particular IHC companion assay by use of an internal control will become necessary. Furthermore, by analogy with ELISA in the clinical laboratory, automation of IHC for companion diagnostics is inevitable, with reagents and protocols subject to increasingly rigorous approval processes, using closed assay systems, that cannot be ‘tweaked’ to get more intense staining in order to compensate for a deficient FFPE process. In the face of poorly controlled sample preparation, the mantra – ‘don’t tweak the protocol; fix the fixation’ – comes to mind.

Footnotes

The author reports no disclosures and no conflicts.

Bibliography

- 1.Oldenhuis CN, Oosting SF, Gietema JA, et al. Prognostic versuss predictive value of biomarkers in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:946–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman RA, Clark J, Chen C. Integrating predictive biomarkers and classifiers into oncology clinical development programmes. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrd3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharmacogenomics Reporter. Draft of Hatch IVD bill – US Federal Legislation. 2011 http://www.genomeweb.com/dxpgx/latest-draft-hatch-ivd-bill-contains-new-regulatory-proposals-pricing-reforms-un.

- 4.FDA U.S Food and Drug Administration. Medical Devices. Classify Your Medical Device. [Code of Federal Regulations][Title 21, Volume 8][Revised as of April 1, 2012][CITE: 21CFR864.1860[CITE: 21CFR864.1860]. Accessed May 2, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/ClassifyYourDevice/default.htm.

- 5.Walcoff SD. Facilitating the Next Generation of Precision Medicine in Oncology. Personalized Medicine in Oncology. 2012;1:43–51. www.personalizedMedOnc.com. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker RL. CDRH; Biomarkers for Devices. Discussion of Forum Workshop: Evaluation of Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints of Chronic disease; Washington DC. June 22, 2010; http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Research/BiomarkersChronDisease/2010-JUN-21/Becker.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CR. Quantifiable Internal Reference Standards for Immunohistochemistry; the measurement of quantity by weight. Applied Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2006;14:253–259. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor CR, Levenson RM. Quantification of immunohistochemistry–issues concerning methods utility and semiquantitative assessment. Histopathology. 2006;49:411–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HercepTest™. Product Package insert. Accessed May 6, 2014. http://www.dako.com/us/ar39/p101510/prod_products.htm?setCountry=true&purl=ar39/p101510/prod_products.htm?undefined&submit=Accept%20country46.

- 10.Gu J, Taylor CR. Practicing pathology in the era of big data and personalized medicine. …Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2014;22:1–9. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams ES, Hegde M. Implementing genomic medicine in pathology. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2013;20:238–244. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182977199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik S, Bryant J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Real-world performance of HER2 testing–National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:852–854. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al. HER2 testing by local, central, and reference laboratories in specimens from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 intergroup adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3032–3038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gown AM. Current issues in ER and HER2 testing by IHC in breast cancer. Modern Pathology. 2008;21:S8–S15. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor CR. Focus on Biospecimens: the issue is the tissue. Observations on the “NCI-NIST fitness for purpose quality assessment standards workshop”. October, 2010. Applied Histochem Mol Morph. 2011;19:95–98. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31820b2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt SM, Robinowitz M, Bogen SA, et al. Quality Assurance for Design Control and Implementation of Immunohistochemistry Assays: Approved Guidelines – Second Edition. Vol. 31. Clinical Lab Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2011. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor CR, Becker KF. Liquid Morphology: Immunochemical Analysis of Proteins extracted from Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded Tissues: combining Proteomics with Immunohistochemistry. Applied Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2011;19:1–9. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181f50883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumeister VM, Parisi F, England AM, et al. Models and techniques. A tissue quality index; an intrinsic control for measurement of effects of pre-analytic variables on FFPE tissue. Lab Invest. 2014;94:467–474. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NordiQC. Nordic Immunohistochemical Quality Control. www.nordiqc.org. Accessed May 14th. 2014.

- 24.UKNEQAS. United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service. www.ukneqas.org.uk. Accessed May 14th. 2014.

- 25.Cartun RW. Negative Reagent Controls in Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Do We Need Them? An Evidence-based Recommendation for Laboratories Throughout the World. Applied Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2014;22:159–161. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torlakovic EE, Francis G, Garratt J, et al. Standardization of Negative Controls in Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Recommendations from the International Ad Hoc Committee. Applied Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2014;22:241–252. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torlakovic EE, Francis G, Garratt J, et al. Standardization of Positive Controls in Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Recommendations from the International Ad Hoc Committee. Applied Immunohistochem Mol Morph. 2014 doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000069. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor CR, Cote RJ. Immunomicroscopy: A diagnostic tool for the surgical pathologist. Third. Elsevier, Saunders; Philadelphia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor CR, Shi SR, Barr N, Wu N. Techniques of Immunohistochemistry: Principles, Pitfalls and Standardization Chapter 1. In: Dabbs DJ, editor. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. Second. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor CR. From microscopy to whole slide digital images: a century and a half of image analysis. Applied Histochem Mol Morph. 2011;19:491–493. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318229ffd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welsh AW, Moeder CB, Kumar S, et al. Standardization of Estrogen Receptor Measurement in Breast Cancer Suggests False-negative results Are a Function of Threshold Intensity Rather Than Percentage of Positive Cells. J Clin Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9706. http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/doi/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.PerkinElmer. Opal Multiplex Tissue Staining. 2014 Accessed May 2, 2014. http://www.perkinelmer.com/catalog/category/id/opal-multiplex-tissue-staining.

- 33.Gerdes MJ, Sevinsky CJ, Sood A, et al. Highly multiplexed single-cell analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cancer tissue. PNAS. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300136110. www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/06/27/1300136110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]