Abstract

Sinorhizobium meliloti is a gram-negative soil bacterium found either in free-living form or as a nitrogen-fixing endosymbiont of a plant structure called the nodule. Symbiosis between S. meliloti and its plant host alfalfa is dependent on bacterial transcription of nod genes, which encode the enzymes responsible for synthesis of Nod factor. S. meliloti Nod factor is a lipochitooligosaccharide that undergoes a sulfate modification essential for its biological activity. Sulfate also modifies the carbohydrate substituents of the bacterial cell surface, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and capsular polysaccharide (K-antigen) (R. A. Cedergren, J. Lee, K. L. Ross, and R. I. Hollingsworth, Biochemistry 34:4467-4477, 1995). We utilized the genomic sequence of S. meliloti to identify an open reading frame, SMc04267 (which we now propose to name lpsS), which encodes an LPS sulfotransferase activity. We expressed LpsS in Escherichia coli and demonstrated that the purified protein functions as an LPS sulfotransferase. Mutants lacking LpsS displayed an 89% reduction in LPS sulfotransferase activity in vitro. However, lpsS mutants retain approximately wild-type levels of sulfated LPS when assayed in vivo, indicating the presence of an additional LPS sulfotransferase activity(ies) in S. meliloti that can compensate for the loss of LpsS. The lpsS mutant did show reduced LPS sulfation, compared to that of the wild type, under conditions that promote nod gene expression, and it elicited a greater number of nodules than did the wild type during symbiosis with alfalfa. These results suggest that sulfation of cell surface polysaccharides and Nod factor may compete for a limiting pool of intracellular sulfate and that LpsS is required for optimal LPS sulfation under these conditions.

Symbioses between leguminous plants and the genera Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Azorhizobium, and Sinorhizobium (collectively called rhizobia) result in the formation of a novel plant organ, referred to as the nodule. Within the nodule, differentiated intracellular forms of rhizobia called bacteroids reduce molecular dinitrogen to ammonia. To gain entry into the plant, the bacteria induce morphological alterations of epidermal cells called root hairs, eliciting the formation of a curled structure referred to as a shepherd's crook. Shepherd's crook formation is followed developmentally by the formation of a tubular ingrowth of the root hair, called an infection thread. The infection thread is occupied by rhizobia and penetrates into the root, allowing bacterial entry into the plant. The bacteria within the infection thread are then released into the plant cytoplasm where they develop into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids (3, 4, 16, 20, 32, 43).

Symbiosis between rhizobia and legumes is dependent on an oligosaccharide signal, called Nod factor. All known Nod factors consist of β-(1,4)-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues that are N-acylated at the nonreducing end (7, 8, 10, 13, 15, 43). Host-specific modifications are then added to this Nod factor structure, which in Sinorhizobium meliloti consists of a 16:2 N-acyl group and 6-O-acetyl group at the nonreducing end of the molecule and a 6-O-sulfate modification at the reducing end (23).

The presence of the sulfate modification on Nod factor is essential for the establishment of the symbiosis on alfalfa and is dependent on the products of three genes, nodH, nodP, and nodQ. The nodH gene product catalyzes the transfer of sulfate to the Nod factor backbone (11, 36), while the nodP and nodQ gene products catalyze the conversion of sulfate and ATP to 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) (37, 38), the activated sulfur donor used by all known carbohydrate sulfotransferases. S. meliloti harbors two copies of nodPQ that are functionally redundant (39).

Sulfuryl modifications are also carried on polysaccharides that constitute the S. meliloti cell surface, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and capsular polysaccharide (K-antigen) (5). Although ubiquitous in mammalian cells, sulfated carbohydrates are rare in bacteria, having only been reported in S. meliloti (5) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (28, 33). Because sulfated carbohydrates have only been reported to date in bacteria that interact with eukaryotic hosts, these molecules have been proposed to facilitate interaction between S. meliloti and alfalfa (5, 18). However, the symbiotic role of carbohydrate sulfation has been difficult to ascertain due to its shared use of biochemical precursors with the Nod factor biosynthetic pathway. Thus, mutations that inactivate either nodP1Q1 or nodP2Q2 result in a decrease in LPS sulfation (18), and mutants lacking both nodP1Q1 and nodP2Q2 show undetectable levels of LPS sulfation (5; D. H. Keating and S. R. Long, unpublished results). However, nodP1Q1 and nodP2Q2 mutations also eliminate the sulfation of Nod factor that is essential for symbiosis with alfalfa (39). Because exogenously supplied Nod factor will not rescue the symbiosis of such mutants, they are of limited utility in the study of symbiotic roles of sulfated carbohydrates.

Recently, a mutant referred to as lps212 was reported to show a decrease in LPS sulfation in vivo and in vitro (18). Furthermore, this mutant showed an inability to enter into an effective symbiosis with the plant host alfalfa, eliciting the formation of nodules that were unable to fix nitrogen. Characterization of the lps212 mutant revealed that it was an allele of the gene lpsL (19), which was subsequently shown to encode an epimerase activity capable of converting UDP-glucuronic acid to UDP-galacturonic acid (18). The inability of the lps212 mutant to produce galacturonic acid (a major substituent of the LPS core) resulted in a structurally altered LPS molecule that was a poor substrate for the sulfotransferase (18). Thus, this mutation disrupted LPS sulfation indirectly, and the symbiotic phenotype could arise either from the alteration in LPS structure, from the reduced sulfation, or both.

To investigate the symbiotic role of sulfated LPS requires the ability to reduce the sulfation of LPS directly, without altering the structure of LPS. Previous data had shown that the sulfation of LPS and Nod factor were catalyzed by distinct enzyme activities (18). Therefore, we wanted to identify and inactivate the gene or genes that encode the LPS sulfotransferase activity. Here we report the identification of an open reading frame (ORF), SMc04267, which encodes an LPS sulfotransferase activity. We have inactivated this ORF and show that the resulting mutant exhibits greatly reduced in vitro sulfotransferase activity. Additionally, we have overexpressed and purified the protein from Escherichia coli and demonstrate that the purified protein functions as a sulfotransferase. Furthermore, we show that mutants that lack the sulfotransferase encoded by ORF SMc04267 exhibit an altered symbiosis, eliciting the formation of nodules at a rate greater than that of the wild type. These data suggest that sulfation of Nod factor and LPS may compete for a common pool of intracellular sulfate. Finally, we demonstrate that S. meliloti contains multiple LPS sulfotransferase activities, displaying a far greater complexity to LPS sulfation than expected. Due to its role in the modification of LPS, we suggest ORF SMc04267 be named lpsS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

All strains used are derivatives of S. meliloti Rm1021 (26) and are described in Table 1. All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (6), tryptone-yeast extract (TY) (2), or M9 (25) medium with antibiotic concentrations as previously described (30).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| S. meliloti | ||

| Rm1021 | Strr SU47 | 26 |

| DKR227 | lpsS::pDW33 | This study |

| DKR229 | lpsS::pDW33/pMB393 | This study |

| DKR230 | lpsS::pDW33/pMB393::lpsS | This study |

| DKR118 | nodP1Q1::Tn5-233 nodP2Q2::Tn5 | This study |

| DKR62 | lpsL::pVO155 | 18 |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21 (DE3) | T7-expressing strain | 40, 41 |

| Plasmid | ||

| pMB393 | Broad-host-range plasmid | 1 |

| pDKR161 | pMB393::lpsS | This study |

| pET16B | T7 expression vector | 40, 41 |

| pCR2.1 | Topo cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pDKR252 | pCR2.1::lpsS-His6 | This study |

| pDW33 | Insertional inactivation plasmid; Hygr | Wells and Long, unpublished |

| pDKR227 | pDW33::lpsS (internal fragment) | This study |

All strains are derived from strain Rm1021.

Strain construction.

Plasmids were introduced into S. meliloti by triparental mating as described previously (9). Strain DKR227 was constructed by introduction of the plasmid pDKR227 (which harbors an internal fragment of lpsS) into Rm1021 and selection for hygromycin-resistant colonies. pDKR227 cannot replicate within S. meliloti, thus hygromycin-resistant colonies arise from recombination events that integrate the plasmid into the genome at the lpsS locus, disrupting the lpsS gene. The insertion events were then confirmed by PCR. Strain DKR118 was constructed by the transduction of nodQ1::Tn5-233 from strain JSS12TR (18, 39) and the nodQ2::Tn5 insertion from strain JSS14 (39) into wild-type strain Rm1021.

Plasmid construction.

The plasmid pDKR227 was constructed by amplifying an internal fragment of lpsS from Rm1021 chromosomal DNA by using the following primers: 5′-AGGTCGACGGAAGGGATTTCATTCA-3′ and 5′-TCGGATCCGCGGCGAGCTCCTCGTA-3′. This fragment was then cloned into plasmid pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), and its presence was verified by colony PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. The lpsS-containing fragment was then isolated from the pCR2.1 plasmid by restriction enzyme digestion with BamHI and SalI and ligated into pDW33 (D. H. Wells and S. R. Long, unpublished results), a hygromycin-resistant derivative of pVO155 (30), digested with the same enzymes.

Plasmid pDKR161 was constructed by amplifying lpsS via PCR using the primers 5′-ACGTCGACGCGAGTTCGGACGGAGA-3′ and 5′-TCGGTACCGCCACGGGAATTCAACT-3′. The fragments were then cloned into plasmid pCR2.1 and verified by colony PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. The pCR2.1::lpsS construct was digested with HindIII and SalI and ligated into plasmid pMB393 (1), digested with the same enzymes.

Plasmid pDKR252 was constructed using the primers 5′-ACGGATCCTTCATGCGAGGTTATCTGCTCC-3′ and 5′-TCGCCCCGGGAATTCAACTCCGCCG-3′ to amplify lpsS. The PCR product was then cloned into pCR2.1. Due to the toxicity of lpsS in E. coli, clones were only recovered in one orientation in pCR2.1, such that the lpsS ORF was located antisense to the lac promoter in the vector. We then digested pET16B with the enzymes BamHI and NdeI to liberate the His6-containing fragment, which was ligated into the pCR2.1 plasmid containing lpsS, digested with the same enzymes.

Preparation of extracts for LPS analysis.

Extracts were prepared according to the method of Reuhs et al. (31) with the following modifications: the cells from 1.5 ml of log-phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5) culture were centrifuged at 8,000 × g and resuspended in 1 ml of water. The cells were again centrifuged at 8,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.15 ml of solution A (0.05 M Na2HPO4, 0.005 M EDTA, pH 7). To the cell suspension was added 0.15 ml of 90% phenol, and the sample was vortexed and then incubated at 65°C for 15 min, followed by incubation on ice for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min, the aqueous phase was removed, and they were dried under vacuum. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of sample loading buffer, and the polysaccharides were fractionated by Tris-Tricine polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as described previously (29). The polysaccharides were then visualized by silver staining (Bio-Rad).

In vivo labeling of LPS.

The wild type and the lpsS mutants were cultured in TY medium to saturation. The cells were then diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in the same medium in a final volume of 1 ml. To this 1-ml sample was added 5 μCi of Na235SO4 (ICN), and the cells were cultured to a final OD600 of 1. For samples prepared under nod gene-inducing conditions, cells were cultured as described above in the presence of 3 μM luteolin (dissolved in ethanol). The LPS was then extracted as described above, the pellets were dissolved in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and 10 μl was fractionated by Tris-Tricine PAGE (29). The PAGE gel was then silver stained (Bio-Rad) to determine the relative amount of extracted LPS and dried, and the incorporated 35SO4 was visualized by autoradiography and quantified by phosphorimaging (Amersham Pharmacia).

Preparation of cell surface protein extracts.

Extracts were prepared as described previously (18). Briefly, cultures of 100 ml of cells were grown in LB medium until the cultures reached stationary phase, and the cells were then collected by centrifugation at 600 × g. The cells were resuspended in 3 ml of Buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol) and disrupted by two passes through a Bionebulizer (Glasco), and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g. A particulate extract was then prepared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min in a tabletop ultracentrifuge (Beckman). The resulting pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of buffer A, and protein concentration was determined by modified Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

In vitro cell surface sulfation assay.

In vitro LPS sulfation was assayed as described previously (18). A portion (2.5 to 10 μg) of a particulate extract was combined with 5 μCi of 35SO4-labeled PAPS (prepared as described previously) (11, 24, 38) and 2 μl of 5× buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 30 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol) in a total reaction volume of 10 μl. The mixture was then allowed to incubate for 30 min at 30°C, and the reaction was stopped by incubation for 2 min at 95°C. SDS sample buffer was then added, and the samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min and fractionated on a SDS-12.5% PAGE gel. The gel was dried, and the incorporation of 35SO4 into LPS in the particulate fraction was measured using a phosphorimager (Amersham Pharmacia). The sulfotransferase activity of the LpsS protein expressed in E. coli was assayed in a similar manner as described above, with the exception that 1 μl of S. meliloti LPS (purified as described above) was added as a sulfate acceptor. E. coli LPS will not function as a sulfate acceptor for the lpsS-encoded activity (G. E. Cronan and D. H. Keating, unpublished results).

Affinity purification of LpsS.

One hundred milliliters of strain BL21(DE3) containing plasmid pDKR252 was cultured to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was then added to 1 mM, and the cultures were allowed to shake for 3 h at 37°C. The cells were then collected by centrifugation at 600 × g, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 3 ml of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol and disrupted by two passes through a Bionebulizer (Glasco), and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g. This extract was then applied to a column containing Ni-NTA nickel affinity resin equilibrated with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol. The flowthrough from this column contained >95% of sulfotransferase activity (Cronan and Keating, unpublished). The pH of the flowthrough fraction was then adjusted to pH 8.5, and 0.5 ml of Ni-NTA nickel affinity resin (QIAGEN) was then added and shaken slowly overnight at 4°C. The resin was collected in a column and washed with 10 column volumes of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol, followed by an additional wash in 10 column volumes of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and 300 mM NaCl. The protein was then eluted with 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.5, in 200-μl fractions. Fractions containing significant amounts of protein, as detected by modified Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), were then dialyzed against 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol using a membrane with a 12,000- to 14,000-molecular-weight cutoff (Spectra/Por) and were assayed for sulfotransferase activity as described above.

Nodulation assay.

The ability of the wild type and lpsS mutants to undergo symbiosis with alfalfa was examined as described previously (12). Briefly, alfalfa seeds were sterilized by shaking in 70% ethanol for 45 min, followed by shaking for 45 min in 20% hypochlorite. The seeds were then washed four times with sterile H2O, allowed to imbibe in H2O overnight, and germinated on an inverted petri dish in the dark. The seedlings were then transferred to slant agar tubes containing buffered nodulation medium (BNM) agar (12). The plants were allowed to grow in the tubes for 2 days and then were inoculated with bacterial strains that were cultured to log phase (OD600, 0.5) in TY medium and then diluted 1/200 in 0.5× BNM liquid medium (12). Fifteen milliliters of this diluted culture of S. meliloti was poured over the plants, and the liquid was then removed from the tube. At various times postinoculation, inoculated plants were observed under a dissecting scope and the numbers of nodules were counted. Ten to 20 plants per treatment were assayed in replicate tubes.

Symbiotic competition assay.

Wild-type Rm1021 and the lpsS mutant were cultured separately overnight and then diluted to an OD600 of 0.5. The cultures were then mixed together in a 1:1, 1:10, and 10:1 ratio of wild type and lpsS mutant, diluted 1:200 into 15 ml of 0.5× BNM (12), which was then used to inoculate alfalfa plants. An aliquot was also removed, serially diluted, and plated for colonies to determine the initial number of CFU in the culture. The inoculated plants were then allowed to undergo symbiosis with the S. meliloti strains for 3 weeks. The nodules from 20 coinoculated plants were then harvested, and the bacteria was recovered by surface sterilization with bleach as described previously (30). A suspension of the recovered bacteria was then diluted and plated on LB plates. The number of colonies of each type was then determined as a result of the hygromycin-resistant nature of the lpsS mutant (due to the insertion of pDW33 into the lpsS gene).

β-Glucuronidase assay.

β-Glucuronidase activity was assayed under free-living conditions according to the method of Jefferson et al. (17). β-Glucuronidase activity was visualized in planta by staining the plant tissue with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide as described previously (30).

RESULTS

The gene lpsS (ORF SMc04267) encodes a carbohydrate sulfotransferase activity.

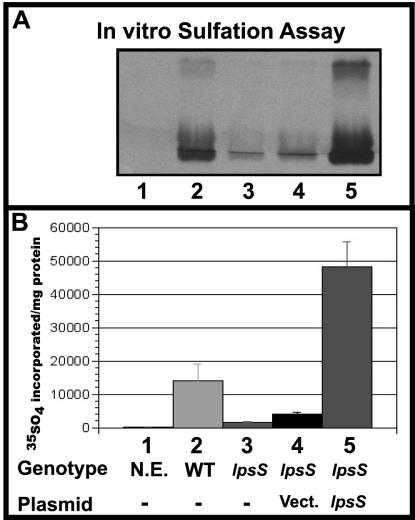

In order to identify candidate genes that could encode the LPS sulfotransferase activity, we examined the S. meliloti sequence database for ORFs with similarity to known sulfotransferases. We identified an ORF SMc04267 (referred to as lpsS [LPS sulfate]) which exhibited 24% amino acid identity to NodH (the sulfotransferase that modifies Nod factor). This ORF also showed significant amino acid identity to ORF Mll3788 from Mesorhizobium loti, ORF SMc01744 from S. meliloti, and ORF RV0295C from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig. 1). We inactivated lpsS by using plasmid pDW33 (Wells and Long, unpublished) (a hygromycin-resistant derivative of the insertional inactivation plasmid pVO155 [30]) and assayed the mutant extract for sulfotransferase activity. The lpsS::pDW33 mutant extracts showed ca. 11% of the sulfotransferase activity seen in the wild type (Fig. 2). Introduction of a wild-type copy of lpsS on plasmid pMB393 (1) into the lpsS::pDW33 mutant resulted in a ca. 300% overexpression of sulfotransferase activity (Fig. 2) compared to that of the wild type. Surprisingly, introduction of the parent vector pMB393 into the lpsS::pDW33 mutant also resulted in a small (ca. 200%), reproducible increase in the sulfotransferase activity, compared to that of the lpsS::pDW33 mutant. However, this activity was still only 25% of that seen in a wild-type strain and ca. 8% of what was seen upon introduction of lpsS in the same vector. These data indicated that lpsS is required for in vitro sulfotransferase activity. However, the lpsS::pDW33 mutant extracts clearly retained a small amount of sulfotransferase activity, suggesting that an additional sulfotransferase activity exists in S. meliloti.

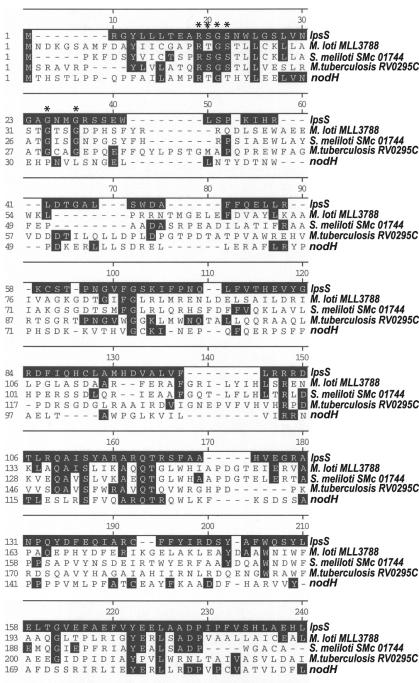

FIG. 1.

Sequence comparison of lpsS and related ORFs. The amino acid sequence of LpsS was compared with three orthologs, ORF Mll3788 from M. loti strain MAFF303099, RV0295C from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and ORF SMc01744 from S. meliloti. No sequence similarity was observed between the C-terminal 25% of LpsS and the orthologs, thus this region was not included in the lineup. Shaded boxes represent amino acid identity. Asterisks represent potential PAPS binding regions.

FIG. 2.

lpsS mutants show reduced LPS sulfotransferase activity in vitro. (A) Extracts prepared from the wild type and lpsS mutants were assayed for sulfotransferase activity as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, no extract (N.E.); lane 2, strain Rm1021 (WT, wild type); lane 3, lpsS::pDW33 mutant; lane 4, lpsS::pDW33 harboring pMB393 (Vect., vector control); lane 5, lpsS::pDW33 harboring plasmid pDKR161 (pMB393/lpsS). (B) Quantification of sulfotransferase activity in lpsS mutant extracts. Sulfotransferase activity was calculated by measuring the incorporation of sulfate into LPS using a phosphorimager and dividing by the amount of protein in the extract. Lanes are the same as for panel A. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Purification of affinity-tagged LpsS.

In order to facilitate biochemical studies, we wanted to purify the enzyme encoded by lpsS. We attempted to construct both N- and C-terminal His6-tagged LpsS (35, 40, 41) and N-terminal glutathione S-transferase-tagged versions of LpsS. Surprisingly, we were unable to construct any of these plasmids. We believe that our inability to construct these plasmids resulted from the instability of lpsS-containing clones in E. coli, although the mechanism of this toxicity is unknown. However, we were able to successfully clone the PCR fragments that resulted from PCR amplification of lpsS into the pCR 2.1 vector (Invitrogen). Ligation of PCR products can yield plasmid inserts in either orientation with respect to the lac promoter present in the vector. However, we only obtained intact clones in the orientation where lpsS was positioned antisense to the lac promoter in pCR2.1, and thus it would not be expressed. Therefore, we cloned the His6-containing fragment from pET16 into the pCR2.1 vector containing lpsS placed antisense to the lac promoter. This resulted in an N-terminal His-tagged version of LpsS that was stable. Although this construct is not expressed in E. coli strains, the His-tagged ORF is directly downstream of the T7 promoter present on pCR2.1. We thus transformed the plasmid into strain BL21(DE3) that expresses T7 polymerase. Transformation into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) resulted in slow-growing colonies that expressed LPS sulfotransferase activity (Fig. 3, lane 1).

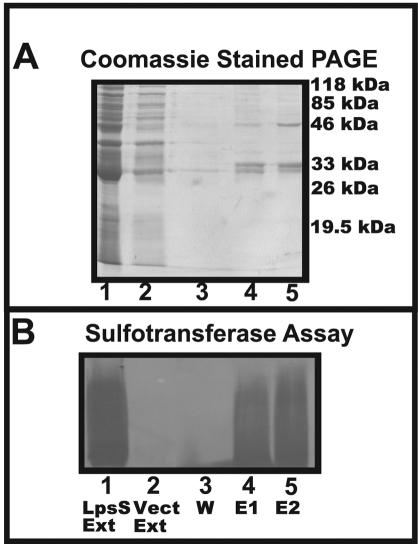

FIG. 3.

Purification of affinity-tagged LpsS. The plasmid encoding an affinity-tagged LpsS was transformed into BL21(DE3) containing an inducible T7 polymerase. Cells harboring this plasmid were cultured at 37°C under inducing conditions, and the protein was purified by nickel affinity chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Purification of affinity-tagged LpsS. Samples from the purification were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, cell extract (Ext) from strain BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pDKR252 (lpsS); lane 2, cell extract from strain BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pET16B (vector control); lane 3, column wash with wash buffer (W). Lanes 4 and 5 represent successive eluted fractions from the nickel column (E1 and E2, respectively). (B) Sulfotransferase activity of purified fractions. The fractions from panel A were dialyzed to remove the imidazole and assayed for sulfotransferase activity. Lanes are as described for panel A.

By using this construct, we were able to overexpress and purify His6-tagged LpsS via nickel-agarose chromatography. Under the conditions recommended by the manufacturer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8), the protein bound the column poorly. However, eliminating the imidazole present in the binding buffer and raising the pH from 8 to 8.5 resulted in the efficient binding of the protein to the column (Fig. 3A). The mechanism of this pH-driven increase in binding is unknown but may result from the relatively high pI of LpsS (pI 8.2) preventing the efficient binding of the protein at pH 8. The protein eluted from the column was enzymatically active (Fig. 3B) and was found to migrate at an approximate molecular mass of 33 kDa (Fig. 3A).

Interestingly, LpsS also eluted from the nickel-agarose column with two other proteins with Mrs of 31,000 and 46,000 (Fig. 3A). These proteins were only observed in purified fractions derived from cells that overexpressed LpsS and thus may be alternative translation products. Purified LpsS was not able to modify the E. coli LPS present in the particulate extract, which is consistent with the structural specificity observed for the native S. meliloti activity (Cronan and Keating, unpublished).

S. meliloti harbors an additional carbohydrate sulfotransferase activity.

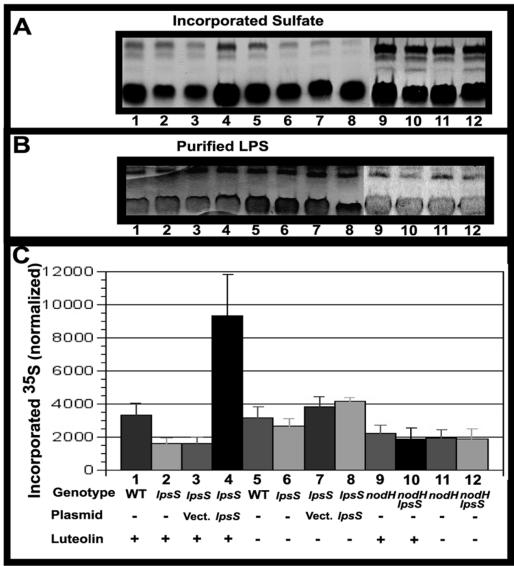

Although, the lpsS::pDW33 mutants show only 11% of the sulfotransferase activity observed in wild-type cells, a low level of sulfotransferase activity was consistently observed in the in vitro assays (Fig. 2). In order to better understand the physiological function of LpsS and the nature of the residual sulfotransferase activity in the lpsS mutant, we measured LPS sulfation in the lpsS::pDW33 mutant in vivo. Wild-type S. meliloti and the lpsS mutant were cultured in the presence of 35SO4. The LPS was then extracted and fractionated on PAGE gels, and the incorporation of 35SO4 was quantified (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, the in vivo assay showed two striking differences from the results seen in the in vitro assays. First, despite exhibiting 11% of wild-type activity in the in vitro assay (Fig. 2), the lpsS::pDW33 mutant showed approximately wild-type levels of sulfated LPS, when corrected for differences in LPS extraction (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 5 and 6). Second, overexpression of LpsS resulted in no change in sulfation when assayed in vivo (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 7 and 8). This contrasts with the 300% increase in sulfotransferase activity observed in in vitro sulfotransferase assays with LpsS-overexpressing extracts (Fig. 2).

FIG. 4.

In vivo sulfation of LPS in the wild type and lpsS mutants. (A) Sulfation of LPS. Wild type, lpsS mutants, and lpsS mutants with plasmids were cultured in the presence of Na235SO4 and in the presence of either 3 μM luteolin solubilized in ethanol or the equivalent amount of ethanol. The LPS was then extracted, fractionated on Tris-Tricine PAGE, and autoradiographed as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 to 4 and 9 to 10 represent samples cultured in the presence of 3 μM luteolin. Lanes 5 to 8 and 11 to 12 represent samples cultured in the presence of ethanol. Lane 1, Rm1021 (WT, wild type); lane 2, lpsS::pDW33 mutant; lane 3, lpsS::pDW33 harboring plasmid pMB393 (Vect., vector control); lane 4, lpsS::pDW33 harboring plasmid pDKR161 (pMB393/lpsS); lane 5, Rm1021 (wild type); lane 6, lpsS::pDW33 mutant; lane 7, lpsS::pDW33 harboring plasmid pMB393 (vector control); lane 8, lpsS::pDW33 harboring plasmid pDKR161 (pMB393/lpsS); lane 9, nodH::Tn5; lane 10, lpsS::pDW33 nodH::Tn5; lane 11, nodH::Tn5; lane 12, lpsS::pDW33 nodH::Tn5. (B) Detection of LPS present in fractionated extracts. The PAGE gel used for autoradiography in panel A was silver stained to detect the LPS present in the fractions. Lanes are the same as for panel A. (C) Quantification of sulfate incorporation into LPS. LPS sulfation was determined by measuring the incorporated radioactivity into LPS using a phosphorimager. The amount of purified LPS was then determined by densitometry of the silver-stained PAGE gel. Values represent average incorporated 35S counts divided by the amount of purified LPS from three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations. The nodH::Tn5 mutation prevents Nod factor sulfation.

Mutants lacking lpsS show reduced sulfation under conditions that promote expression of nod genes.

Although the lpsS::pDW33 mutant showed wild-type levels of LPS sulfation under free-living conditions, it seemed possible that lpsS might play a role in sulfation during symbiosis. During the initial interaction of S. meliloti with alfalfa, flavonoids released by the plant induce transcription of the nod genes that encode the enzymes responsible for both the synthesis and sulfate modification of Nod factor (which, in turn, triggers the formation of root nodules). We asked whether sulfation of LPS was affected in the presence of luteolin, a plant-derived flavonoid that is a potent inducer of nod gene transcription. We cultured wild-type S. meliloti and the lpsS::pDW33 mutant in the presence of 35SO4 and in the presence and absence of luteolin. We found that the sulfation of wild-type S. meliloti LPS was unaffected by the addition of luteolin to the growth medium (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 1 and 5). However, the lpsS::pDW33 mutant showed ca. 50% of the LPS sulfation seen in the wild type cultured in the presence of luteolin (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 1 and 2). Interestingly, introduction of a plasmid-borne form of the lpsS gene not only restored sulfation to a wild-type level under luteolin-inducing conditions (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 3 and 4) but also resulted in a ca. 300% increase in sulfation (similar to what was seen in vitro [Fig. 2]). To insure that the altered sulfation did not result from a decrease in the growth rate of the lpsS::pDW33 mutant under conditions of luteolin induction, we examined the growth of the wild type and the lpsS::pDW33 mutant in the presence and absence of luteolin. We found that luteolin did not appreciably affect the growth rate of the wild type or the lpsS::pDW33 mutant under these conditions (Cronan and Keating, unpublished).

One explanation for the luteolin-promoted decrease in LPS sulfation seen in the lpsS::pDW33 mutant was an inability of the residual LPS sulfotransferase to compete for a limiting pool of intracellular sulfate under conditions of nod gene expression. The expression of NodH, the sulfotransferase that modifies Nod factor, is increased in the presence of luteolin (11, 36). In the absence of LpsS, the activity that carries out this residual LPS sulfotransferase activity may compete poorly with NodH for intracellular sulfate, and this could lead to the decreased amount of LPS sulfation seen in the lpsS::pDW33 mutant under conditions that promote nod gene expression. This hypothesis predicts that blocking the sulfation of Nod factor by inactivating NodH activity would restore sulfation of LPS under nod gene-inducing conditions. We therefore constructed a lpsS::pDW33 nodH::Tn5 double mutant and then measured the incorporation of sulfate into LPS in this strain in the presence and absence of luteolin in the growth medium (Fig. 4C). Although nodH::Tn5 lpsS::pDW33 double mutants show an overall decrease in LPS sulfation compared to the wild type (which may result from the reduced growth rate of the strain), the double mutant did not show a significant decrease in LPS sulfation under conditions of nod gene expression. These data suggest that the decrease in LPS sulfation observed in the lpsS::pDW33 mutant may result from an inability of the residual LPS sulfotransferase activity to compete with NodH for a limiting pool of intracellular sulfate.

lpsS mutants elicit the production of a greater number of nodules than wild type.

The reduced sulfation observed in the lpsS::pDW33 mutant in the presence of luteolin suggested that the mutant might show an altered ability to undergo symbiosis with alfalfa. We therefore tested the symbiotic ability of the lpsS mutant. The lpsS::pDW33 mutant was able to elicit the formation of nodules capable of fixing nitrogen, as judged by the pink color of the nodules (resulting from leghemoglobin production) and the green color of the plants when assayed for growth on medium lacking nitrogen (Cronan and Keating, unpublished), as well as measurement of plant dry weight. (Dry weights [milligrams] of the plants were as follows: wild type, 38.6 ± 6.95; lpsS::pDW33, 42.1 ± 7.4; mock inoculated, 5.4 ± 0.5. The alfalfa plants were inoculated, grown under nitrogen-limited conditions, and dried at 80°C, and then plant dry weight was measured.) In addition, the infection threads elicited by the lpsS::pDW33 mutant tagged with either β-galactosidase or green fluorescent protein were indistinguishable from those produced by the wild type (Cronan and Keating, unpublished). Thus, lpsS is not required for symbiosis with alfalfa under laboratory conditions.

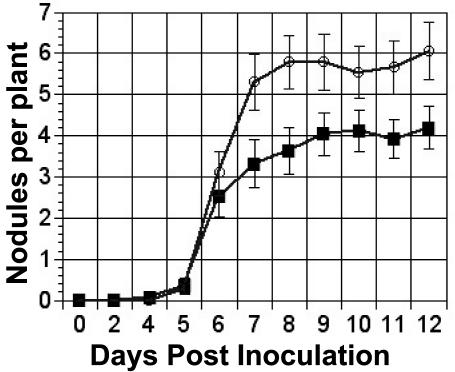

We also utilized a competition assay to further characterize the symbiotic ability of the lpsS::pDW33 mutant. Following coinoculation of the wild type and the lpsS::pDW33 mutant onto alfalfa plants, we harvested the nodules and subsequently isolated the bacteria from within the nodules. The lpsS::pDW33 mutant is tagged with a hygromycin resistance marker that allowed for a simple differentiation between the two strains of inoculating bacteria. We found that the lpsS::pDW33 mutant was not outcompeted by the wild type (Table 2) under conditions where the wild type and lpsS::pDW33 were inoculated in a 1:1 ratio. These data suggest that the lpsS::pDW33 mutant, despite its decreased LPS sulfation under conditions of luteolin induction, does not show a symbiotic defect detectable by any of these methods. However, the lpsS::pDW33 mutant did show one symbiotic phenotype. We found that the number of nodules produced by the lpsS mutant was consistently greater than that produced by the wild type (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we found that complementation with a wild-type version of lpsS corrected this phenotype (Cronan and Keating, unpublished).

TABLE 2.

Quantification of bacteria recovered from nodules following coinoculation of wild type and lpsS::pDW33 mutanta

| Inoculated strains | No. of wild-type bacteria | No. of lpsS::pDW33 bacteria | Ratio of wild type/lpsS::pDW33 bacteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 96 | 0 | NAb |

| lpsS::pDW33 | 0 | 96 | NA |

| Wild type/lpsS::pDW33 (1:1) | 324 | 455 | 0.412 |

| Wild type/lpsS::pDW33 (10:1) | 460 | 31 | 0.936 |

| Wild type/lpsS::pDW33 (1:10) | 68 | 487 | 0.122 |

Numbers represent the bacteria recovered from 20 nodules.

NA, not applicable.

FIG. 5.

Increased nodule formation in lpsS mutant. Strain Rm1021 and the lpsS::pDW33 mutant were inoculated onto alfalfa, and the number of nodules were counted as described in Materials and Methods. Dark squares, Rm1021; open circles, lpsS::pDW33. Error bars represent standard errors.

Expression of lpsS during free-living and symbiotic conditions.

The inactivated form of lpsS was constructed with pDW33, which allows for the formation of transcriptional fusions between the target gene and uidA (which encodes β-glucuronidase) (30). We used this transcriptional fusion to measure the expression of lpsS under a variety of growth conditions. We found that the lpsS fusion was highly expressed under free-living conditions (Table 3) and did not show a significant alteration in expression between log-phase (OD600, 0.5) and stationary-phase growth (OD600, 2.5). In addition, we measured the expression of the lps::uidA fusion during growth in the presence or absence of luteolin. The expression of the lpsS::uidA fusion was unchanged by the presence of luteolin in the growth medium (Table 4). The uidA fusion can also be detected in planta by the use of X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid), allowing qualitative examination of the expression of lpsS during symbiosis. Thus, we infected alfalfa plants with the lpsS::pDW33 mutant and stained the nodules for β-glucuronidase activity. β-Glucuronidase activity was observed throughout the nodule (Cronan and Keating, unpublished), demonstrating that lpsS was expressed in planta.

TABLE 3.

Expression of lpsS::uidA fusion during log-phase and stationary-phase growtha

| Strain | Fusion | GUS activity during:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log phaseb | Entry into stationary phasec | Late stationary phased | ||

| Rm1021 | None (background) | 8.1 | ND | 7.5 |

| DKR227 | lpsS::uidA | 3,407 ± 247 | 3,138 ± 112 | 3,044 ± 55 |

| DKR50e | SMa21243::uidA | 91.5 ± 2.5 | 119.9 ± 7 | 403.2 ± 21.2 |

Activity is in Miller units (27). GUS, β-glucuronidase.

Log phase corresponds to an OD600 of 0.5.

Entry into stationary phase corresponds to an OD600 of 1.5. ND, not done.

Late stationary log phase corresponds to an OD600 of 2.5.

DKR50 contains a fusion to an ORF (SMb21243) previously shown to be up-regulated upon entry into stationary phase (45).

TABLE 4.

Expression of lpsS::uidA fusion in the presence and absence of luteolina

| Strain | Genotype | Luteolinb | Expressionc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rm1021 | Wild type | + | 35.5 ± 2.346 |

| Rm1021 | Wild type | − | 82.3 ± 71.72 |

| DKR227 | lpsS::uidA | + | 4,190.4 ± 1,147.15 |

| DKR227 | lpsS::uidA | − | 3,692.9 ± 258.5 |

Activity is in Miller units (27).

Cells were cultured in the presence of luteolin (solublized in ethanol) or the equivalent amount of ethanol.

β-Glucuronidase activity was measured in cells cultured to late stationary phase (OD600, 2.5).

DISCUSSION

By using a bioinformatical approach, we have identified a gene that encodes an LPS sulfotransferase activity. Mutants lacking this enzyme show 11% of the in vitro sulfotransferase activity observed in the wild type, yet they retain approximately normal levels of sulfated LPS under free-living conditions. The lpsS mutant also exhibited a reduction in LPS sulfation under conditions of nod gene expression, yet it only showed a single symbiotic phenotype, an ability to elicit the formation of a greater number of nodules than the wild type on the host plant alfalfa.

A comparison of LpsS and mammalian carbohydrate sulfotransferases does not suggest any prominent sequence conservation. The PAPS binding site consensus GXXGXXK (22), which is often conserved in estrogen sulfotransferases, is not found in LpsS (although, the sequence GXXG is found in LpsS and orthologs [Fig. 1]). Recently, two additional PAPS binding domains were identified by sequence comparisons of mammalian carbohydrate and estrogen sulfotransferases (14). Regions of LpsS with substantial sequence identity to these domains could not be identified. However, a region of LpsS with similarity to the putative 5′-phosphosulfate binding domain of N-acetylglucosamine sulfotransferases was observed (Fig. 1). This region of LpsS as well as the GXXG region are candidate PAPS binding domains and will be important targets for mutagenesis efforts in the future. The lack of sequence identity could imply that the bacterial enzymes are enzymatically distinct from their mammalian counterparts. Alternatively, despite the lack of sequence conservation between the bacterial enzymes and their eukaryotic counterparts, the tertiary structures of these proteins may be similar.

The LpsS sulfotransferase exhibits significant sequence identity to ORF Mll3788 from M. loti. M. loti is a symbiont of Lotus japonicus, an emerging model legume for the study of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Interestingly, some strains of M. loti have the ability to enter into two morphologically distinct types of nitrogen-fixing symbioses (determinate and indeterminate). It will be interesting to see if M. loti contains sulfated carbohydrates and if they are required for either of these types of symbiosis. LpsS also shows significant sequence identify to ORF RV0295C from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell surface carbohydrates of M. tuberculosis have been shown in some cases to contain sulfate modifications, some of which have been implicated as virulence factors (28). Furthermore, a recent study has shown that ORF RV0295C encodes a sulfotransferase activity (28a). Finally, LpsS shows significant sequence identity to S. meliloti ORF SMc01744. ORF SMc01744 is not required for sulfation of S. meliloti LPS, and its current function is not known. However, S. meliloti capsular polysaccharide (K-antigen) is also modified by sulfate, and ORF 01744 may be involved in this sulfation event, a possibility we are currently examining. Although the functions of these ORFs are speculative at present, LpsS may be the founding member of a family of bacterial sulfotransferases that modify cell surface carbohydrates.

One of the most surprising results of this study was that LPS sulfation is carried out by multiple enzyme activities. Two distinct lpsS mutant alleles were constructed by plasmid-based insertional mutagenesis that result in truncations of the C-terminal half and the C-terminal two-thirds of LpsS, respectively. Both of these mutants retained a low level of sulfotransferase activity in vitro and wild-type levels of sulfated LPS when assayed in vivo (Cronan and Keating, unpublished). Therefore, we believe that an additional sulfotransferase activity is present in S. meliloti. However, conclusive demonstration of this will require the identification and characterization of this additional sulfotransferase activity(ies).

Although lpsS appears dispensable for sulfation during free-living growth, mutants lacking lpsS showed only 50% of the LPS sulfation seen in the wild type when cultured in the presence of luteolin (the inducer of nod gene transcription). Although the expression of lpsS is unaffected by the presence of luteolin in the growth medium, it remains possible that expression of the enzyme(s) that catalyze the residual LPS sulfation may be reduced in the presence of luteolin. Flavonoids have been shown to reduce the expression of some rhizobial genes (21), so this remains a viable possibility. Once we have identified the gene(s) responsible for this activity, we will test this hypothesis.

Alternatively, the reduced LPS sulfation may result from a competition between the NodH-dependent sulfate modification of Nod factor and the sulfation of LPS. In the absence of LpsS, the residual LPS sulfotransferase activity may be unable to compete effectively with NodH for a limiting pool of sulfate, resulting in increased levels of sulfated Nod factor and a decrease in sulfated LPS. Nodule biosynthesis in alfalfa is dependent on sulfated Nod factor, so an increase in Nod factor sulfation could explain the increased number of nodules seen in the lpsS mutant. Additionally, two studies have shown that a reduction in sulfation leads to a significant decrease in secreted Nod factor (34, 44). Therefore, an increase in Nod factor sulfation may lead to an increased amount of Nod factor biosynthesis or secretion, which could lead to a greater number of nodules. Consistent with this hypothesis is the finding that introduction of mutations in nodH (which is responsible for the sulfation of Nod factor) into the lpsS::pDW33 mutant eliminated the 50% reduction in LPS sulfation observed during conditions of nod gene expression. However, although Nod factor is the only substrate of NodH that has been identified, it remains possible that NodH may modify additional carbohydrates in S. meliloti.

Finally, the lpsS mutant does not show an obvious symbiotic defect under laboratory conditions, other than the ability to elicit the production of more nodules than the wild type. The lack of a symbiotic phenotype may suggest that sulfation of LPS is not required for symbiosis. Alternatively, the lpsS mutant may not result in a sufficient decrease in sulfation of LPS to produce a symbiotic defect. The majority of S. meliloti mutants with LPS defects that have been studied to date show quantitative reductions in LPS sulfation and symbiosis with alfalfa (D. H. Keating, G. R. O. Campbell, and G. C. Walker, unpublished results). However, it is currently unclear whether the symbiotic defects observed in these LPS mutants result from the decrease in sulfation, from alterations in LPS structure, or both. A conclusive determination of the role of sulfation of LPS in symbiosis will require the isolation of mutants that completely lack sulfated LPS. The lpsS mutant will provide a foundation for the discovery of the gene(s) that encodes the residual sulfotransferase activity. The identification of these genes is under way.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guy Townsend and Maike Müller for helpful comments on the manuscript, Derek Wells and Sharon Long for the gift of plasmid pDW33, and Joseph Mougous and Carolyn Bertozzi for communicating the data regarding M. tuberculosis ORF RV0295C prior to publication.

This study was carried out using start-up funds from Loyola University Chicago.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett, M. J., V. Oke, and S. R. Long. 2000. New genetic tools for use in the Rhizobiaceae and other bacteria. BioTechniques 29:240-242, 244-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beringer, J. E. 1974. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 84:188-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewin, N. J. 1991. Development of the legume root nodule. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 7:191-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewin, N. J. 1992. Nodule formation in legumes. Encycl. Microbiol. 3:229-248. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cedergren, R. A., J. Lee, K. L. Ross, and R. I. Hollingsworth. 1995. Common links in the structure and cellular localization of Rhizobium chitolipooligosaccharides and general Rhizobium membrane phospholipid and glycolipid components. Biochemistry 34:4467-4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 7.de Bruijn, F. 1991. Biochemical and molecular studies: symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2:184-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denarie, J., and J. Cullimore. 1993. Lipo-oligosaccharide nodulation factors: a minireview of a new class of signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Cell 74:951-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ditta, G., S. Stanfield, D. Corbin, and D. R. Helinski. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7347-7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downie, J. A. 1994. Signalling strategies for nodulation of legumes by rhizobia. Trends Microbiol. 2:318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrhardt, D. W., E. M. Atkinson, K. F. Faull, D. I. Freedberg, D. P. Sutherlin, R. Armstrong, and S. R. Long. 1995. In vitro sulfotransferase activity of NodH, a nodulation protein of Rhizobium meliloti required for host-specific nodulation. J. Bacteriol. 177:6237-6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrhardt, D. W., E. M. Atkinson, and S. R. Long. 1992. Depolarization of alfalfa root hair membrane potential by Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors. Science 256:998-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher, R. F., and S. R. Long. 1992. Rhizobium—plant signal exchange. Nature 357:655-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunwell, J. R., V. L. Rath, J. Rasmussen, Z. Cabrilo, and C. R. Bertozzi. 2002. Characterization and mutagenesis of Gal/GlcNAc-6-O-sulfotransferases. Biochemistry 41:15590-15600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashi, S. 1993. (Brady)Rhizobium-plant communications involved in infection and nodulation. J. Plant Res. 106:206-211. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch, A. M. 1992. Developmental biology of legume nodulation. New Phytol. 122:211-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jefferson, R. A., S. M. Burgress, and D. Hirsch. 1986. β-glucuronidase from Escherichia coli as a gene-fusion marker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:8447-8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keating, D. H., M. G. Willits, and S. R. Long. 2002. A Sinorhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharide mutant altered in cell surface sulfation. J. Bacteriol. 184:6681-6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kereszt, A., E. Kiss, B. L. Reuhs, R. W. Carlson, A. Kondorosi, and P. Putnoky. 1998. Novel rkp gene clusters of Sinorhizobium meliloti involved in capsular polysaccharide production and invasion of the symbiotic nodule: the rkpK gene encodes a UDP-glucose dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 180:5426-5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kijne, J. W., R. Bakhuizen, A. A. N. van Brussel, H. C. J. CanterCremers, C. L. Diaz, B. S. de Pater, G. Smit, H. P. Spaink, S. Swart, C. A. Wiffelman, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1992. The Rhizobium trap: root hair curling in root-nodule symbiosis. Soc. Exp. Biol. Semin. Ser. 48:267-284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, H., Y. Naciri-Graven, W. J. Broughton, and X. Perret. 2004. Flavonoids induce temporal shifts in gene-expression of nod-box controlled loci in Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol. Microbiol. 51:335-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu, K., W. J. Driscoll, Y. C. Koh, and C. A. Strott. 1994. A P-loop related motif (GxxGxxK) highly conserved in sulfotransferases is required for binding the activated sulfate donor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 204:1178-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerouge, P., P. Roche, C. Faucher, F. Maillet, G. Truchet, J. C. Prome, and J. Denarie. 1990. Symbiotic host-specificity of Rhizobium meliloti is determined by a sulphated and acylated glucosamine oligosaccharide signal. Nature 344:781-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyh, T. S., J. C. Taylor, and G. D. Markham. 1988. The sulfate activation locus of Escherichia coli K12: cloning, genetic, and enzymatic characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 263:2409-2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniatis, T. E., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Meade, H. M., S. R. Long, G. B. Ruvkun, S. E. Brown, and F. M. Ausubel. 1982. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 149:114-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, J. H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Mougous, J. D., R. E. Green, S. J. Williams, S. E. Brenner, and C. R. Bertozzi. 2002. Sulfotransferases and sulfatases in mycobacteria. Chem. Biol. 9:767-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Mougous, J. D., and C. R. Bertozzi. Nat. Struct. Biol., in press.

- 29.Niehaus, K., A. Largares, and A. Puhler. 1998. A Sinorhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharide mutant induces effective nodules on the host plant Medicago sativa (alfalfa) but fails to establish a symbiosis with Medicago truncatula. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:906-914. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oke, V., and S. R. Long. 1999. Bacterial genes induced within the nodule during the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:837-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reuhs, B. L., R. W. Carlson, and J. S. Kim. 1993. Rhizobium fredii and Rhizobium meliloti produce 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid-containing polysaccharides that are structurally analogous to group II K antigens (capsular polysaccharides) found in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:3570-3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridge, R. 1992. A model for legume root hair growth and Rhizobium infection. Symbiosis 14:359-373. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivera-Marrero, C. A., J. D. Ritzenthaler, S. A. Newburn, J. Roman, and R. D. Cummings. 2002. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel glycolipid sulfotransferase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 148:783-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roche, P., F. Debelle, F. Maillet, P. Lerouge, C. Faucher, G. Truchet, J. Denarie, and J. C. Prome. 1991. Molecular basis of symbiotic host specificity in Rhizobium meliloti: nodH and nodPQ genes encode the sulfation of lipo-oligosaccharide signals. Cell 67:1131-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg, A. H., B. N. Lade, D. S. Chui, S. W. Lin, J. J. Dunn, and F. W. Studier. 1987. Vectors for selective expression of cloned DNAs by T7 RNA polymerase. Gene 56:125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schultze, M., C. Staehelin, H. Rohrig, M. John, J. Schmidt, E. Kondorosi, J. Schell, and A. Kondorosi. 1995. In vitro sulfotransferase activity of Rhizobium meliloti NodH protein: lipochitooligosaccharide nodulation signals are sulfated after synthesis of the core structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2706-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwedock, J., and S. R. Long. 1990. ATP sulphurylase activity of the nodP and nodQ gene products of Rhizobium meliloti. Nature 348:644-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwedock, J. S., C. Liu, T. S. Leyh, and S. R. Long. 1994. Rhizobium meliloti NodP and NodQ form a multifunctional sulfate-activating complex requiring GTP for activity. J. Bacteriol. 176:7055-7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwedock, J. S., and S. R. Long. 1992. Rhizobium meliloti genes involved in sulfate activation: the two copies of nodPQ and a new locus, saa. Genetics 132:899-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Studier, F. W., and B. A. Moffatt. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Studier, F. W., A. H. Rosenberg, J. J. Dunn, and J. W. Dubendorff. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanson, J. A., J. Tu, J. Ogawa, R. Sanga, R. F. Fisher, and S. R. Long. 1987. Extended region of nodulation genes in Rhizobium meliloti 1021. I. Phenotypes of Tn5 insertion mutants. Genetics 117:181-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijn, I., L. das Nevas, A. van Kammen, H. Franssen, and T. Bisseling. 1993. Nod factors and nodulation in plants. Science 260:1764-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wais, R. J., D. H. Keating, and S. R. Long. 2002. Structure-function analysis of Nod factor-induced root hair calcium spiking in Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Plant Physiol. 129:211-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells, D. H., and S. R. Long. 2003. Mutations in rpoBC suppress the defects of a Sinorhizobium meliloti relA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 185:5602-5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]