Abstract

Background:

Clinical guidelines should be updated to maintain their validity. Our aim was to estimate the length of time before recommendations become outdated.

Methods:

We used a retrospective cohort design and included recommendations from clinical guidelines developed in the Spanish National Health System clinical guideline program since 2008. We performed a descriptive analysis of references, recommendations and resources used, and a survival analysis of recommendations using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results:

We included 113 recommendations from 4 clinical guidelines with a median of 4 years since the most recent search (range 3.9–4.4 yr). We retrieved 39 136 references (range 3343–14 787) using an exhaustive literature search, 668 of which were related to the recommendations in our sample. We identified 69 (10.3%) key references, corresponding to 25 (22.1%) recommendations that required updating. Ninety-two percent (95% confidence interval 86.9–97.0) of the recommendations were valid 1 year after their development. This probability decreased at 2 (85.7%), 3 (81.3%) and 4 years (77.8%).

Interpretation:

Recommendations quickly become outdated, with 1 out of 5 recommendations being out of date after 3 years. Waiting more than 3 years to review a guideline is potentially too long.

Clinical guidelines are “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by systematic reviews of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”1 As with systematic reviews, guidelines become outdated as new evidence is published and require a periodic reassessment to remain valid.2–4

Updating clinical guidelines is a complex process that includes identifying new evidence, assessing whether it has an impact on the recommendations and assessing whether an update is required.5,6 Methodological handbooks include little guidance as to how to review and update guidelines, other than to do so periodically.5,7–9

Despite scant research, guideline programs endorse 3 to 5 years as a reasonable period after which guidelines should be reviewed.5,10 This generic guidance is based on a study published more than 10 years ago that investigated how often guidelines needed to be updated.4 We therefore developed a strategy to assess the validity of recommendations and estimated how long it took before recommendations became out of date.

Methods

Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of recommendations from clinical guidelines. We included recommendations from English translations of guidelines developed in the Spanish National Health System clinical guidelines program since 2008. All of the guidelines are available from the GuiaSalud library (www.guiasalud.es/). We stratified guidelines by topic (cancer and palliative care, cardiovascular disease, mental health and metabolic disease) and by year of publication (2008 and 2009). When multiple guidelines per strata were available, we randomly selected one.

We classified recommendations according to topic (as stated previously), strength (A, B, C, D, or good practice point as graded using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]system),11 clinical purpose (prevention, screening, treatment or other) and number of pertinent references to which it was linked (turnover).

We performed a stratified random sampling of recommendations by number of references linked per recommendation and by guideline topic. The sample size required for the study was 112 recommendations (α risk of 0.95; precision ± 0.05 units in a 2-sided test; reference population size 249; expected proportion 0.154; estimated replacement rate 1%).

Assessment of recommendations

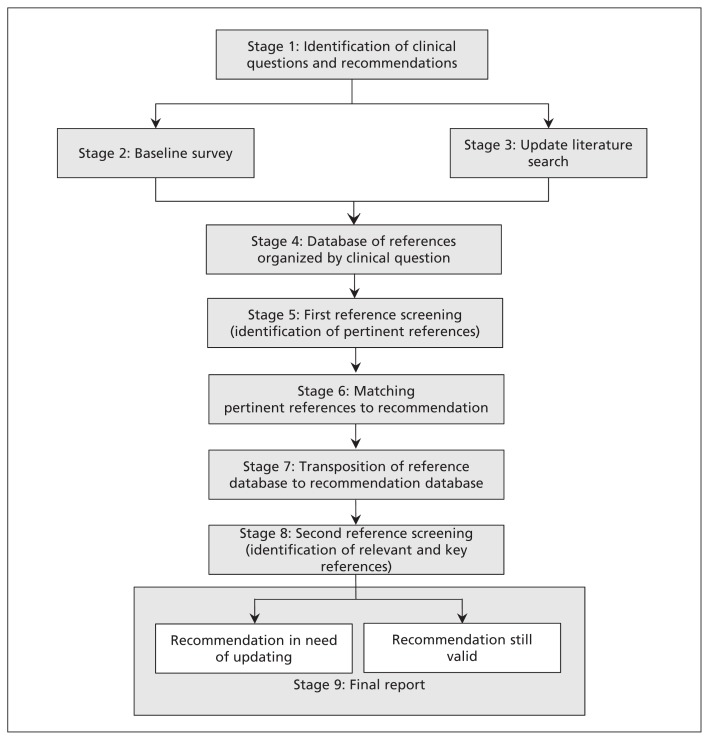

We developed a nine-stage strategy to assess the validity of recommendations (Figure 1). Stage 1 involved the identification of clinical questions and recommendations. In stage 2, for each set of included guidelines, we conducted a baseline survey in a convenience sample of 6 clinical experts from the original guideline group (4 of whom represented the different areas covered by the guideline, and 2 of whom were external). The experts evaluated whether they considered the recommendations to be up to date and stated whether they knew of any new studies that could modify the recommendations. In stage 3, we recovered the original exhaustive literature searches for each of the clinical questions addressed in the guidelines. Information specialists, preferably from the group who worked on the original guideline, performed the database searches and filtered the results by study design (randomized controlled trial or systematic review). Stage 4 involved clustering the references obtained from the baseline survey and literature search to identify and eliminate duplicates. We then evaluated whether references were pertinent to the topic of interest, the study design and the type of publication (original article or abstract) in stage 5. In stage 6, we matched pertinent references with the corresponding recommendations. In stage 7, we analyzed the reference database to find recommendations without references, recommendations with a low turnover (≤ median number of references per recommendation) or recommendations with a high turnover (> median number of references per recommendation). In stage 8, we designed a form to assess and classify pertinent references. Relevant references were defined as those that could be used when considering an update to a recommendation, but that would not necessarily trigger a potential update. Key references were those that could potentially trigger an update. In addition, the form asked respondents to consider potential changes in the recommendation in relation to population, intervention, comparison, outcome, quality of evidence, direction and strength of the recommendation.12 Each form was assessed by 2 clinical experts and 1 guideline methodologist, and disagreements were resolved by consensus during online meetings. In stage 9, using the results of the second reference screening in stage 8, we classified recommendations as either in need of updating (with one or more key references linked) or still valid (without key references linked). A final report was then sent to the corresponding institutions that developed the guidelines and the clinicians who collaborated on the study.

Figure 1:

Strategy to assess the validity of recommendations.

A more complete description of our strategy is available in the previously published protocol.13

Outcome

Our primary outcome was the median length of time for recommendations to become out of date.

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the data. We calculated either absolute and relative frequencies or median and range, as appropriate. We compared recommendations in need of updating versus those still valid by topic, strength of recommendation, clinical purpose and turnover using the Pearson χ2 test.

We calculated the response rate for the baseline survey and considered a reply to be valid only if more than 20% of our questions had been answered.

We evaluated agreement between the opinions of the clinical experts and the methodologist as to what was a relevant or key reference. We used a decision algorithm to resolve disagreements (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.140547/-/DC1). We followed the guidelines proposed by Landis and Koch14 to evaluate agreement (κ 0–0.20, poor agreement; κ 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; κ 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; κ 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; κ > 0.80, almost perfect agreement).

We performed a survival analysis to determine our primary outcome. We defined an event as the identification of a key reference for a specific recommendation. We considered the inception date to be the date of the original literature search. The obsolescence date was the publication date of the first key reference. The last observation date was the date on which an updated search was started. We calculated the survival time for a potential update (obsolescence date – inception date) and for still valid recommendations (last observation date – inception date). We calculated the estimated rate of survival of recommendations using the Kaplan–Meier method. We used the log-rank test to analyze differences between survival curves according to guideline topic, strength of recommendation, clinical purpose and turnover.

We assessed the resources used to support our strategy. We recorded the number of hours spent on each stage and the number of researchers involved. We imputed 10 minutes per reference when time spent was not reported. We calculated the number of references assessed per hour per researcher and reported the median and range.

We accepted p values of less than 0.05 as significant in all calculations. We performed the analyses using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and assessed the agreement (κ coefficient and the 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) using EPIDAT 4.0 (Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia, Spain and Pan American Health Organization, Washington, DC). We calculated sample size using GRANMO 7 (www.imim.cat/ofertadeserveis/software-public/granmo).

Results

We identified 14 clinical guidelines in March 2011 (www.guiasalud.es/). We excluded 6 guidelines that were not available in English and stratified the remaining guidelines by topic and year of publication. Our selection process is summarized in Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.140547/-/DC1). Because multiple guidelines were available for the stratum “mental health 2008,” we randomly selected a single publication. We included 4 guidelines in our final cohort: management of major depression in adults (2008);15 prostate cancer treatment (2008);16 secondary prevention of stroke (2009) (primary prevention was excluded);17 and prevention and treatment of obesity in childhood and adolescence (2009).18

The included guidelines addressed 87 clinical questions and made 249 recommendations (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.140547/-/DC1). In 3 guidelines, the original literature search started in 2007;15–17 the literature search for the guideline on obesity in childhood and adolescence began in 2008.18

Our random sample of recommendations included 43 clinical questions and 113 recommendations (Table 1). Most of the recommendations were classified as a good practice point (n = 51 [45.1%]) and were about treatment (n = 59 [52.2%]) or prevention (n = 47 [41.6%]). These proportions were similar independent of turnover (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of recommendations

| Characteristic | Guidelines topic and year of publication | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depression in adults, 200815 | Obesity in childhood and adolescence, 200918 | Prostate cancer treatment, 200816 | Secondary prevention of stroke, 200917 | ||

| Sample size, no. | |||||

| Clinical questions | 8 | 10 | 16 | 9 | 43 |

| Recommendations | 26 | 29 | 36 | 22 | 113 |

| SIGN strength of recommendations, no. (%) | |||||

| A | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.9) | 9 (40.9) | 18 (15.9) |

| B | 8 (30.8) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (8.3) | 5 (22.7) | 22 (19.5) |

| C | 2 (7.7) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (9.1) | 9 (8.0) |

| D | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.4) | 11 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (11.5) |

| Good practice point | 11 (42.3) | 19 (65.5) | 15 (41.7) | 6 (27.3) | 51 (45.1) |

| Clinical purpose, no. (%) | |||||

| Prevention | 0 (0.0) | 25 (86.2) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (100.0) | 47 (41.6) |

| Screening | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Treatment | 23 (88.5) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (52.2) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) |

| Turnover, no. (%) | |||||

| No references | 4 (15.4) | 7 (24.1) | 11 (30.6) | 6 (27.3) | 28 (24.8) |

| Low | 12 (46.2) | 11 (37.9) | 13 (36.1) | 8 (36.4) | 44 (38.9) |

| High | 10 (38.5) | 11 (37.9) | 12 (33.3) | 8 (36.4) | 41 (36.3) |

Note: SIGN = Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Baseline survey

We contacted a total of 24 clinical experts for our baseline survey and had a response rate of 70.8% (17 respondents) (Appendix 3). Respondents reported that they were aware of new and relevant studies for 140 recommendations (56.2%), but they considered this new evidence to be sufficient to warrant an update in only 68 recommendations (27.3%) (Appendix 3). After screening for pertinence, we selected 49 of the 189 references suggested by the clinical experts (25.9%). In addition, we included 21 (42.9%) references that were not identified in the updated literature search (Appendix 3).

Literature search

We recovered the original search strategy for 3 clinical guidelines15–17 and developed a new search for the remaining set of guidelines.18 Searches were done by different information specialists, with the exception of the clinical guidelines on secondary prevention of stroke,17 for which the original information specialist was available (Appendix 3).

For each set of guidelines, we ran exhaustive literature searches for the complete year in which the original search was completed (2007–2008) onward (2011–2012). Search periods had a median of 4 years (range 3.9–4.4 yr). We retrieved a total of 39 136 references (range 3343–14 787) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Results of the updated literature search, reference screening and reference classification

| Characteristic | Guidelines topic and year of publication | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depression in adults, 200815 | Obesity in childhood and adolescence, 200918 | Prostate cancer treatment, 200816 | Secondary prevention of stroke, 200917 | ||

| References found during updated exhaustive literature search, no. | 11 243 | 9 763 | 3 343 | 14 787 | 39 136 |

| First reference screening from all recommendations, no. (%) | |||||

| Duplicate | 3 846 (34.2) | 2 445 (25.0) | 286 (8.6) | 1 582 (10.7) | 8 159 (20.8) |

| Excluded | 6 976 (62.0) | 6 981 (71.5) | 2 901 (86.8) | 12 940 (87.5) | 29 798 (76.1) |

| Included (pertinent references) | 260 (2.3) | 334 (3.4) | 102 (3.1) | 255 (1.7) | 951 (2.4) |

| New* | 161 (1.4) | 3 (0.0) | 54 (1.6) | 10 (0.1) | 228 (0.6) |

| Second reference screening from sample recommendations, no. (%) | n = 192 | n = 292 | n = 106 | n = 78 | n = 668 |

| Pertinent references | 73 (38.0) | 93 (31.8) | 22 (20.8) | 12 (15.4) | 200 (29.9) |

| Relevant references† | 106 (55.2) | 167 (57.2) | 73 (68.9) | 53 (67.9) | 399 (59.7) |

| Key references‡ | 13 (6.8) | 32 (11.0) | 11 (10.4) | 13 (16.7) | 69 (10.3) |

| Key references, type of study, no. (%) | n = 13 | n = 32 | n = 11 | n = 13 | n = 69 |

| Randomized controlled trial | 8 (61.5) | 23 (71.9) | 9 (81.8) | 4 (30.8) | 44 (63.8) |

| Systematic review | 5 (38.5) | 9 (28.1) | 2 (18.2) | 9 (69.2) | 25 (36.2) |

| Key references, recommendation change, no. (%)§ | |||||

| Population | 1 (7.7) | 4 (12.5) | – | 1 (7.7) | 6 (8.7) |

| Intervention | 12 (92.3) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (18.2) | 7 (53.8) | 26 (37.7) |

| Comparison | – | 2 (6.3) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (7.2) |

| Outcome | 9 (69.2) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (27.3) | – | 14 (20.3) |

| Quality of the evidence | 11 (84.6) | 25 (78.1) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (38.5) | 46 (66.7)¶ |

| Direction of the recommendation | 9 (69.2) | – | – | – | 9 (13.0) |

| Strength of the recommendation | 11 (84.6) | 14 (43.8) | 7 (63.6) | 6 (46.2) | 38 (55.1) |

References that may be related to new recommendations.

All relevant references were also pertinent.

All key references were also pertinent and relevant.

One reference may change more than one issue.

Fourteen key references changed the quality of evidence.

Assessment of references

First screening

We identified 951 (2.4%) pertinent references, which could be matched to 187 (75.1%) recommendations (Table 2). The number of pertinent references per recommendation was between 2 and 7 (Appendix 3).

Second screening

From the 668 pertinent references linked to our random sample of 113 recommendations, we identified 69 key references (10.3%) (Table 2 and Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.140547/-/DC1]. Agreement between clinical experts and the methodologist as to what was a key reference was poor (range 0.1–0.2) (Appendix 3). Forty-four of the key references (63.8%) were randomized controlled trials and 46 (66.7%) changed the quality of the evidence supporting the corresponding recommendation (Table 2). We identified 9 references that changed the direction of one recommendation about the pharmacological treatment of depression (Table 2).

Assessment of recommendations

We identified 25 (22.1%) recommendations that were considered in need of updating. Most of these recommendations were graded B for strength or considered a good practice point (n = 9 [36.0%] for both), were about prevention (n = 15 [60.0%]) and included a high number of linked references (n = 18 [72.0%]) (Table 3). Recommendations with a high turnover were more likely to require a potential update than those with a low turnover. Guideline topic, the strength of recommendations and clinical purpose were not associated with the need to update.

Table 3:

Status of 113 recommendations included in the sample

| Variable | Status, no. (%) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Still valid | Potential for update | ||

| Guidelines topic | |||

| Mental health, n = 26 | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | 0.32 |

| Metabolic disease, n = 29 | 21 (72.4) | 8 (27.6) | |

| Cancer and palliative care, n = 36 | 29 (80.6) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, n = 22 | 15 (68.2) | 7 (31.8) | |

| SIGN strength of recommendations | n = 88 | n = 25 | |

| A | 15 (17.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0.11 |

| B | 13 (14.8) | 9 (36.0) | |

| C | 6 (6.8) | 3 (12.0) | |

| D | 12 (13.6) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Good practice point | 42 (47.7) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Clinical purpose | |||

| Prevention | 32 (36.4) | 15 (60.0) | 0.14 |

| Screening | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Treatment | 49 (55.7) | 10 (40.0) | |

| Others | 4 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Turnover | |||

| Without references | 28 (31.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 |

| Low turnover | 37 (42.0) | 7 (28.0) | |

| High turnover | 23 (26.1) | 18 (72.0) | |

Note: SIGN = Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Pearson χ2 test.

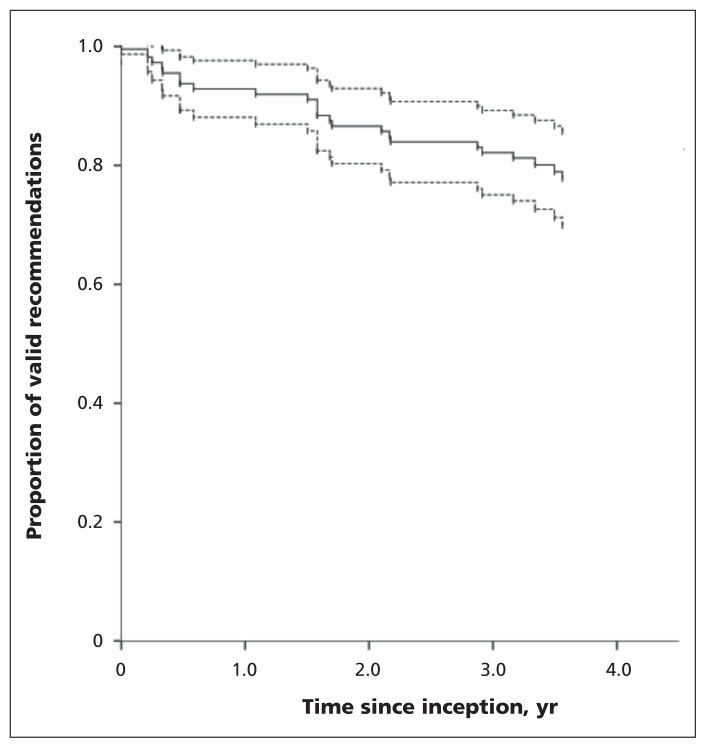

The median follow-up time of recommendations was 3.6 years (range 0–4.4 yr). At 1 year, 92.0% (95% CI 86.9%–97.0%) of the recommendations were still valid. This probability gradually decreased at 2, 3 and 4 years (85.7%, 81.3% and 77.8%, respectively) (Figure 2 and Appendix 3). The guideline topic, strength of the recommendations, clinical purpose and recommendation turnover were not associated with differences between survival curves.

Figure 2:

Kaplan–Meier survival curve (solid line) of clinical guideline recommendations with 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines).

Use of resources

A total of 43 people (4 information specialists, 16 guidelines methodologists and 26 expert clinicians) participated in our process, for a total of 1170.9 hours (Appendix 3). The most time-consuming task was the first reference screening and matching of the references with recommendations (566.5 h) (Appendix 3).

Interpretation

We evaluated the validity of a random sample of recommendations from clinical guidelines produced by a national guideline development program. Previous studies that have analyzed the survival time of clinical guidelines have suggested that guidelines should be reassessed every 3 to 5 years.4,19 However, these studies considered the guidelines as the unit of analysis rather than the individual recommendations, and the authors did not use an exhaustive search strategy. Our analysis of recommendation-level data showed that recommendations quickly became outdated (about 20% of the recommendations were out of date within 3 years).

Recommendations with a high turnover were more likely to require an update than those with a low turnover, which suggests that fields with high research activity are likely areas in which effects are not conclusive or where alternative interventions are being developed. Guideline developers should hence tailor their strategies accordingly. Factors such as topic, strength of the recommendation and clinical purpose were not predictors of the need for updating.

Previous work studying the lifespan of systematic reviews showed that an updating signal appeared in 23% of the publications within 2 years, and that cardiovascular medicine had the shortest time before an updating signal.2 In addition, a recent evaluation of guidelines for interventions developed by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) showed that updated recommendations generally had a larger body of evidence published since they were originally published.20 Our results agree with these findings, with similar signals for the speed of decay and topics with a high turnover. Recent studies showed that recommendations based on scarce evidence were more likely to be updated,21,22 and a large proportion of good practice points in our sample of recommendations needed to be updated (36% [9/25]).

Finally, empirical investigations of the speed of updating evidence-based point of care summaries shows that these resources undergo more frequent surveillance than clinical guidelines do.3 These resources are popular among clinicians, and being up to date is a possible reason for their success. Thus, clinical guidelines should be updated more frequently if they are to be useful to clinicians.

Limitations

We did not implement our strategy prospectively in newly published guidelines, we limited our search by type of study, including only randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, and we defined obsolescence date as the date when the first key reference was published.

Our sample is limited to recommendations from 4 guidelines developed by the Spanish National Health System’s clinical guideline program, and our findings might not be generalizable to other settings. However, this potential limitation is mitigated because our sample covers broad areas such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, mental health and lifestyle and behavioural issues.

We used the original exhaustive literature searches to identify new evidence. These searches yielded many off-target references and were resource intensive. Previous research suggests that restrictive search strategies are sufficient to monitor the literature for updating clinical guidelines and systematic reviews.23,24 Nevertheless, available research is limited, and more studies about the performance of restrictive strategies are needed.13

The baseline surveys among clinical experts to assess which recommendations were considered to be out of date or to suggest relevant references had different response rates for each of the clinical guidelines, and the surveys did not provide additional useful information. However, this strategy could be useful if implemented prospectively.

For the purpose of this study, we manually built our own databases of references and recommendations. All of the Guidelines were available through a Web portal (www.guiasalud.es/) and were accessible as PDF files. However, we did not have a guideline-authoring tool or a common electronic platform with the functionalities needed to automate the process, increasing the burden of the work.

Conclusion

Guideline developers should implement strategies to survey the validity of the recommendations. A time line of 6 to 12 months for the surveillance of new evidence could be reasonable and should be tailored depending on the speed with which new research is published. This approach would likely decrease the workload for each update and, most importantly, assure the validity of recommendations.

Institutions that develop guidelines may benefit from working with online platforms that organize the guidelines, recommendations, references and searches in databases. Ideally, this technology would semiautomate the updating process, thereby optimizing efficiency.25–27

Finally, our framework provides a structured strategy to assess the validity of recommendations and provides detailed guidance for replicating the process. Our strategy could also be used to develop and evaluate more efficient ways of maintaining the validity of guidelines.13

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mercedes Cabañas (Técnicas Avanzadas de Investigación en Servicios de Salud [TAISS], Madrid, Spain) and Joanna Kelly (Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Glasgow, UK) for their support in developing and running the exhaustive literature searches, and Carolyn Newey for her help editing the manuscript. Laura Martínez García is a doctoral candidate at the Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Preventive Medicine Department, Universitat Aunònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Laura Martínez García, Andrea Juliana Sanabria, David Rigau, Leticia Barajas-Nava, Ivan Solà and Pablo Alonso-Coello have received research grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS PI10/00346). R. Brian Haynes and Jennifer Lawson have received research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No other competing interests were declared.

Contributors: Laura Martínez García, Pablo Alonso-Coello, David Rigau and Ivan Solà conceived the idea of the study. All of the authors contributed to the development of the study. Laura Martínez García and Pablo Alonso-Coello drafted the manuscript. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Members of the Updating Guidelines Working Group: L. Martínez García, A.J. Sanabria, E. García Álvarez, M.M. Trujillo-Martín, I. Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, A. Kotzeva, D. Rigau, A. Louro-González, L. Barajas-Nava, P. Díaz del Campo, M.-D. Estrada, I. Solà, J. Gracia, F. Salcedo-Fernandez, J. Lawson, R.B. Haynes, P. Alonso-Coello, M. Álvarez Ariza, J. Argente Oliver, P. Armario García, E. Arrieta Antón, A. Balaguer Santamaría, A. Borque, J.C. Buñuel Álvarez, A. Cervera Álvarez, M.E. De Las Heras Liñero, L. Dopico, L.S. Eddy Ives, R. Escó Barón, I. Ferreira González, F. Ferrer, M.J. Gil Sanz, F.I. Lago Deibe, J.C. Martí Canales, A. Martínez, G.A. Martos Moreno, T. Mejuto Marti, A. Morales Ortiz, L.A. Rioja Sanz, J. Rioja Zuazu, A. Rodríguez González, J.L. Rodríguez-Arias Palomo and A. Sáenz Cusí.

Funding: This project is funded by research grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS PI10/00346 to Pablo Alonso-Coello) and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (R. Brian Haynes). Laura Martínez García and Andrea Juliana Sanabria are funded by Río Hortega research contracts from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM11/00035 and CM12/00168 respectively). Pablo Alonso-Coello is funded by a Miguel Servet research contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP09/00137).

Data sharing: The dataset is available from the corresponding author at laura.martinez.garcia@cochrane.es.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guideline we can trust. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, et al. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banzi R, Cinquini M, Liberati A, et al. Speed of updating online evidence based point of care summaries: prospective cohort analysis. BMJ 2011;343:d5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA 2001;286:1461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernooij RWM, Sanabria AJ, Solà I, et al. Guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review of methodological handbooks. Implement Sci 2014;9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Working Group on CPG Updates. Updating clinical practice guidelines in the Spanish National Health System: methodology handbook. Madrid (Spain): National Plan for the National Health System of the Spanish Ministry for Health and Social Policy; Aragon Health Sciences Institute (I+CS); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker M, Neugebauer EA, Eikermann M. Partial updating of clinical practice guidelines often makes more sense than full updating: a systematic review on methods and the development of an updating procedure. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso-Coello P, Martínez García L, Carrasco JM, et al. The updating of clinical practice guidelines: insights from an international survey. Implement Sci 2011;6:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansari S, Rashidian A. Guidelines for guidelines: Are they up to the task? A comparative assessment of clinical practice guideline development handbooks. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e49864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez García L, Arévalo-Rodríguez I, Solà I, et al. Strategies for monitoring and updating clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2012;7:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidelines by topic. Edinburgh (Scotland): Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network — Healthcare Improvement Scotland; 2013. Available: www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html (accessed 2014 Feb. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines 15: Going from evidence to recommendation — determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez García L, Sanabria AJ, Araya I, et al. Strategies to assess the validity of recommendations: a study protocol. Implement Sci 2013;8:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Working Group on the Management of Major Depression in Adults. Clinical practice guideline on the management of major depression in adults. Madrid (Spain): National Plan for the SHN of the MHCA; Axencia de Avaliación de Tecnoloxías Sanitarias de Galicia (avalia-t); 2008. Clinical Practice Guidelines in the Spanish SHN: avalia-t No 2006/06. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Working group of the Clinical Practice Guideline on Prostate Cancer Treatment. Clinical practice guidelines on prostate cancer treatment. Madrid (Spain): National Plan for the NHS of the MSC; Aragon Institute of Health Sciences (I+CS); 2008. Clinical Practice Guidelines in the NHS I+CS No 2006/02. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Development Group of the Stroke Prevention Guideline. Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre, coordinator. Clinical practice guideline for primary and secondary prevention of stroke. Madrid (Spain): Quality Plan for the National Health System of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs; Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research; 2008. Clinical Practice Guideline: AATRM Number 2006/15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Working Group of the Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Childhood and Juvenile Obesity. Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre, coordinator. Clinical practice guideline for the prevention and treatment of childhood and juvenile obesity. CPGs: Quality Plan for the Spanish National Healthcare System of the Spanish Ministry for Health and Social Policy; Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment; 2009 Clinical Practice Guideline: CAHTA no. 2007/25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alderson LJ, Alderson P, Tan T. Median life span of a cohort of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidelines was about 60 months. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyratzopoulos G, Barnes S, Stegenga H, et al. Updating clinical practice recommendations: Is it worthwhile and when? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2012;28:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez García L, McFarlane E, Barnes S, et al. Updated recommendations: an assessment of NICE clinical guidelines. Implement Sci 2014;9:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuman MD, Goldstein JN, Cirullo MA, et al. Durability of class I American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guideline recommendations. JAMA 2014;311:2092–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gartlehner G, West SL, Lohr KN, et al. Assessing the need to update prevention guidelines: a comparison of two methods. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newberry SJ, Ahmadzai N, Motala A, et al. Surveillance and identification of signals for updating systematic review: implementation and early experience. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Available: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm (accessed 2014 Feb. 4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treweek S, Oxman AD, Alderson P, et al. Developing and Evaluating Communication Strategies to Support Informed Decisions and Practice Based on Evidence (DECIDE): protocol and preliminary results. Implement Sci 2013;8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Creating clinical practice guidelines we can trust, use, and share: a new era is imminent. Chest 2013;144:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G, Vandvik PO. Creating clinical practice guidelines: problems and solutions. Chest 2013;144:365–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.